Final report for GNE22-283

Project Information

Urban agroforestry (UAF) systems are multifunctional landscapes that improve urban environments and provide diverse ecosystem services and benefits to humans and other species. The inclusion of native productive plants, grown for food, medicine, or other uses, in UAF systems can increase the ecological quality of the landscape and ecosystem services provided, as well as prevent harm caused by non-native species; however, many urban agriculturalists engaging in annual crop production may be unfamiliar with UAF alternatives, and even UAF practitioners may be unaware of the benefits provided by native plants, or willing to accept ecological tradeoffs associated with non-native plants for their high productivity value. UAF systems are complex social-ecological systems, and as such, both social and ecological methods must be employed in studies of these systems. Quantitative online surveys, qualitative on site interviews, and ecological surveys were used to answer four main research questions:

- What are current perceptions and knowledge of UAF systems and native productive plants among stakeholder groups?

- What are barriers to the cultivation of agroforestry systems and native productive plants in urban environments?

- How do agroforestry practitioners adjudicate the tradeoffs between the productive, ecological, and social functions of these landscapes?

- How does the proportion of native vs. non-native plants correlate to the overall ecological quality of UAF sites?

Answers to these questions will benefit farmers and others in the green industries by identifying new crops for nursery and commercial production and will contribute to academic publications and educational resources for gardeners, agroforesters, and green industry professionals.

- Through a quantitative survey, broadly characterize urban agriculturalists’ and green industry professionals’ use, knowledge, and perceptions of urban agroforestry and native productive plants in those systems and identify possible barriers to the more widespread use of both UAF practices and native productive plants in the landscape.

- Through qualitative interviews, explore with urban agriculturists topics covered in the quantitative survey but at greater depth. Pertinent information collected will include knowledge of native productive plants and their uses, motivations for plant selections, and potential trade-offs related to the inclusion of higher proportions of native plants in urban agroforestry systems.

- Identify overlooked native species with economic potential for the green industries, such as those that have productive value in the form of food, medicine, materials, or have other cultural significance. Develop strategies for promoting adoption of UAF practices and use of native plants within urban landscapes, including marketing strategies based on evidence collected, such as motivations for growing fruit crops.

- Analyze correlations between proportion of native plant species in an urban agroforestry system and other indicators of ecological integrity and sustainability, such as complexity of vegetation structure and soil health. Compare ecological quality between annual urban agriculture systems, urban agroforestry systems, and urban agroforestry systems with high proportions of native plants included.

The purpose of this project was to advance the field of urban agroforestry, ultimately leading to increased sustainability in urban agricultural practices and new opportunities for farmers and others in the green industries. With increasing urbanization, urban landscapes must provide more supporting, regulating, productive, and cultural ecosystem services formerly provided by rural landscapes, and thus it is essential that the former landscapes be designed for multifunctionality. Urban agriculture can improve access to nature and empower communities while improving food access, but home and community gardens and urban farms are often ecologically simple landscapes dominated by production functions and by non-native, annual crops. Because of their vertical complexity, agroforestry systems, such as food forests, combining woody plants with annual and perennial herbaceous crops may offer greater ecological benefits, particularly when they include native productive plants grown for food, medicine, or other uses. Agroforestry systems may also be psychologically preferred because of humans’ innate preference for landscapes with trees. However, gardeners’ and landscape and nursery professionals’ lack of familiarity with the design and benefits of these systems and furthermore lack of knowledge of native productive plants may present barriers to their more widespread cultivation.

Research

- A quantitative survey of urban gardeners/farmers and landscape/nursery professionals in the Northeast was conducted in spring 2023 to determine existing knowledge and perceptions of both urban agroforestry systems and native productive plants. The survey was developed with the guidance of a graduate committee during the fall semester of 2022 using tailored design methods (Dillman et al., 2014). IRB exempt status was received on March 24, 2023. Recruitment fliers were distributed via social media and email targeting relevant groups, such as master gardeners, urban agriculture service providers, permaculture groups, and other interest groups, e.g., The Wild Ones, garden clubs, etc. The survey was conducted online using Qualtrics software and the questionnaire collected information about practitioners and sites, including demographics, basic information about the site, history of urban agroforestry and gardening, use and perceptions of native and non-native edible or medicinal plants, management practices, information sources and gardening networks, primary purpose served by the site, and plant sources. Questions for gardeners and farmers differed from those for landscapers and nursery professionals, with a filter question included to route different populations through the survey. Survey responses will generate descriptive statistics regarding participation in UAF and native plant gardening with socio-demographic factors serving as independent variables. Responses regarding UAF and native plant knowledge and perceptions served as dependent variables. For example, the survey included a self assessment of native plant knowledge scored on a Likert scale. Analyses were conducted in summer 2025. The survey also collected contact information as the responses were used to identify practitioners with whom to conduct more in-depth qualitative interviews.

- Qualitative interviews were conducted with practitioners located in the U.S. Northeast and identified through the online survey. Interview participants were selected based on location and type of urban agriculture carried out on their site. The interview schedule was developed in fall of 2022 with the guidance of a graduate committee. Interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). The questions were similar to those included in the survey, but more in depth, to allow us to gain a deeper understanding of the current use of UAF practices and native productive plants in UAF systems, determine motivations for plant selections, and explore potential trade-offs in ecosystem services, e.g., production vs. habitat provisioning, related to including higher proportions of native productive plants. Interviews began in late spring of 2023, continued into late fall of 2023, and were conducted in person at the production site for most participants. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and coded using ATLAS.ti software, to apply deductive codes based on the social-ecological systems (Ostrom, 2007; Ostrom, 2009; Partelow, 2018) and affordance theory frameworks (Gibson, 1979; Chemero, 2003; Hadavi et al., 2015; Stoltz & Schaffer, 2018), and then inductively coded based on re-emerging themes found in the interviews (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019; Vila-Henninger, 2019).

- Site visits and interviews also included a walking tour of the site to inventory the species and collect ethnobotanical data on the use of native productive species. Ethnobotany involves the study of social and cultural knowledge of local ecosystems (Martin, 2004). Different plant species serve a variety of roles in urban environments, and by studying these roles we can better understand the importance of these species (Taylor & Lovell, 2013). Ethnobotanical surveys and interviews are a mechanism to access the important cultural information gardeners possess on these species (Vogl et al., 2004). Collecting this type of data can also identify potentially overlooked species that have important cultural uses beyond food production, such as medicine, crafting, and decoration, and thus contribute to wider biocultural conservation and more diverse ecosystem services (Hemmelgarn & Mensell, 2021). A deeper social and cultural exploration can help us understand additional barriers to creating agroforestry systems that better support native biodiversity (Raymond et al. 2018), and analyzing the decision making process behind garden and landscape designs can help identify opportunities to promote more ecologically sound practices that benefit both humans and non-humans alike (Goddard et al., 2013).

- Ecological surveys also provided data for an analysis of the ecological integrity of each site, which can be used to measure the correlation between species inventories, proportion of native plant species, and ecological structure and function of the site. Survey data will be analyzed to measure native vs. non-native species richness, structural complexity of the vegetation, and soil health. Native vs. non-native species richness will be determined based on data from the species inventory. Soil samples were collected and used to develop a brief soil profile for each site including physical and chemical indicators of soil quality and testing for common contaminants found in urban areas (Tresch et al., 2018).

References

Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 15(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326969eco1502_5

DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The Tailored Design Method (4th ed.). Wiley.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin.

Goddard, M. A., Dougill, A. J., & Benton, T. G. (2013). Why garden for wildlife? social and ecological drivers, motivations and barriers for biodiversity management in residential landscapes. Ecological Economics, 86, 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.07.016

Hadavi, S., Kaplan, R., & Hunter, M. C. (2015). Environmental affordances: A practical approach for design of nearby outdoor settings in urban residential areas. Landscape and Urban Planning, 134, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.10.001

Hemmelgarn, H. L., & Munsell, J. F. (2021). Exploring ‘beyond‐food’ opportunities for biocultural conservation in urban forest gardens. Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/uar2.20009

Linneberg, M. S., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/qrj-12-2018-0012

Martin, G. J. (2004). Ethnobotany: A methods manual. Earthscan.

Ostrom, E. (2007). A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15181–15187. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0702288104

Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325(5939), 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133

Partelow, S. (2018). A review of the social-ecological systems framework: Applications, methods, modifications, and challenges. Ecology and Society, 23(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-10594-230436

Raymond, C. M., Diduck, A. P., Buijs, A., Boerchers, M., & Moquin, R. (2018). Exploring the co-benefits (and costs) of home gardening for biodiversity conservation. Local Environment, 24(3), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1561657

Stoltz, J., & Schaffer, C. (2018). Salutogenic affordances and sustainability: Multiple benefits with edible forest gardens in urban green spaces. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02344

Taylor, J. R., & Lovell, S. T. (2013). Urban Home Food Gardens in the Global North: Research Traditions and future directions. Agriculture and Human Values, 31(2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-013-9475-1

Taylor, J. R., & Lovell, S. T. (2021). Designing multifunctional urban agroforestry with people in mind. Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/uar2.20016

Tresch, S., Moretti, M., Le Bayon, R.-C., Mäder, P., Zanetta, A., Frey, D., Stehle, B., Kuhn, A., Munyangabe, A., & Fliessbach, A. (2018). Urban Soil Quality Assessment—a comprehensive case study dataset of Urban Garden Soils. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00136

Vila-Henninger, L. A. (2019). Turning Talk into “Rationales”: Using the Extended Case Method for the Coding and Analysis of Semi-Structured Interview Data in ATLAS.ti. Bulletin De Me ́thodologie Sociologique, 143, 28–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0759106319852887

Vogl, C. R., Vogl-Lukasser, B., & Puri, R. K. (2004). Tools and methods for data collection in ethnobotanical studies of Homegardens. Field Methods, 16(3), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x04266844

Survey Results

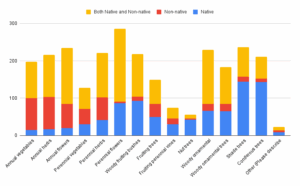

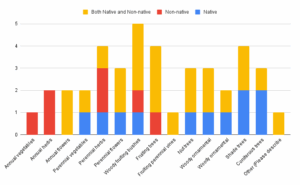

Participants in the online survey (n=372) included gardeners (n=319), farmers (n=8), nursery professionals (n=5), landscape professionals (n=19), community gardeners (n=17), and food foresters (n=3). Among gardeners who provided the primary purpose of their garden (n=311) the most common answers were annual vegetable garden (30%) and habitat garden (30%), followed by ornamental garden (18%), agroforest/food forest made up only 3% of responses. Gardeners reported obtaining plants from local nurseries, nonprofit organizations, online nurseries, and big box stores at relatively equal rates. Gardeners and farmers were asked to categorize plant types included on their gardens and/or farms as native or non-native (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Survey results for gardeners asked “For each plant type included in your garden, indicate, to the best of your knowledge, whether the plants in your farm include plants that are natives and/or non-native to your area.”

Figure 2. Survey results for farmers asked “For each plant type included in your farm, indicate, to the best of your knowledge, whether the plants in your farm include plants that are natives and/or non-native to your area.”

When asked how important including native plants in landscape designs for clients most responded that it was extremely (55%) or very (33%) important with clients specifically requesting native plants always (18%), often (41%), sometimes (29%), or rarely (12%). Overall landscapers felt extremely (41%,44%), very (47%,39%), or moderately (12%,17%) informed about the benefits of native plants and the risks of non-native plants within the landscape. Respondents felt extremely (20%), very (40%), or moderately (40%) confident in relaying information on the benefits of native pants to customers. Over 70% felt extremely or very confident in relaying information about the risks of non-native plants to clients, with 22% feeling moderately confident and 6% feeling only slightly confident.

Nursery professionals reported vastly different percentages of sales made up by native plants, including 1%, 5-10%, 75%, and 98% with native plants being requested by customers always (25%), often (25%), or sometimes (50%). Nursery professionals reported being extremely (40%), or very (60%) informed about the benefits of native plants, and extremely (20%), very (60%), or moderately (20%) informed about the risks of non-native and invasive plants. Respondents felt extremely (20%), very (40%), or moderately (40%) confident in relaying this information to customers.

Table 1. Survey Demographics

|

Total |

Gardener |

Farmer |

Nursery Professional |

Landscape Professional |

|

|

Gender |

|||||

|

Male |

12.0% |

11.0% |

33.3% |

0.0% |

5.6% |

|

Female |

87.7% |

88.7% |

66.7% |

100.0% |

83.3% |

|

Non-binary / third gender |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

5.6% |

|

Prefer not to say |

0.3% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

5.6% |

|

Race |

|||||

|

White |

94.0% |

94.2% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

83.3% |

|

Black or African American |

1.3% |

1.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

0.7% |

0.7% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Asian |

1.7% |

1.4% |

16.7% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

0.3% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Other |

4.0% |

4.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

16.7% |

|

Highest Level of Education |

|||||

|

No high school diploma |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

High school diploma or equivalent |

1.0% |

1.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Some college |

4.6% |

4.8% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

5.6% |

|

Associate’s degree |

3.6% |

3.7% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

39.9% |

40.1% |

33.3% |

20.0% |

61.1% |

|

Master’s degree |

36.3% |

36.4% |

16.7% |

60.0% |

33.3% |

|

Doctoral or professional degree |

14.5% |

13.9% |

50.0% |

20.0% |

0.0% |

Interview Results

As of October 2025 8 qualitative interviews were conducted with food foresters throughout the northeastern United States, including practitioners in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, and Pennsylvania. Of the practitioners interviewed 3 tended to their own private residential food forests, and 5 were stewards of local community food forests. Motivations for the private sites were mostly access to fresh food and medicine for immediate family, though at least one private practitioner also mentioned providing food and resources for community members. Compared to the residential food forests, community food forests were usually in much more urban settings and thus associated more highly with challenges of these locations such as pressure from invasive species and space constraints.

Key themes identified from the interview transcripts include the following:

- Community Engagement and Education:

- Many interview participants emphasized the importance of community involvement in gardening and food forest projects. They discussed how these spaces serve as educational resources for local residents, including children and families, fostering a sense of community and shared responsibility.

- Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health:

- There was a strong focus on increasing biodiversity within the gardens and food forests. Interview participants mentioned the introduction of native plants, the importance of pollinators, and the role of various species in supporting local wildlife. The discussions highlight efforts to create habitats that benefit both plants and animals, reflecting a holistic approach to gardening.

- Sustainability and Resilience:

- The theme of sustainability was prevalent, with many participants discussing practices that minimize environmental impact, such as using native plants, organic gardening methods, and permaculture principles. There was also a focus on resilience, particularly in the context of extreme weather events and adapting gardening practices to changing environmental conditions.

- Food Security and Self-Sufficiency:

- Participants expressed a desire to grow food for personal consumption and community distribution, emphasizing the importance of food security. They discuss the benefits of growing their own food as a way to reduce reliance on commercial food systems and enhance local food sovereignty.

- Cultural and Historical Context:

- Some discussions with participants touched on the cultural significance of certain plants and gardening practices, including the incorporation of traditional knowledge and the importance of preserving local heritage through gardening.

- Adaptation and Change:

- The interviews reflect a theme of adaptation, with participants discussing how their gardening practices and goals evolve over time in response to challenges such as environmental variability, soil health, and community needs.

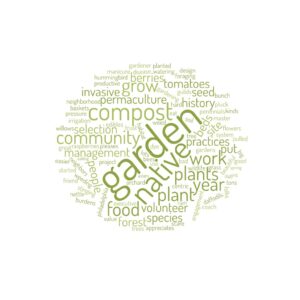

Figure 3. A word cloud generated using keywords detected in each interview transcript. Larger words were found in a greater number of interviews.

Plant Inventory Results

Across the 17 food forest sites, we recorded 996 plant records representing an average of 59 unique plant taxa per site, with a range of 12 to 87 taxa per site. The three most common species were all native; the fruiting tree pawpaw (Amsonia triloba) was recorded on 13 of the sites while common milkweed (Asclepias syriacus) and fox grape (Vitis labrusca) and its cultivars were each found on 12 sites. Elderberry was also recorded on 12 sites and was considered to be native in all its occurrences, though no attempt was made to distinguish between the morphologically—and possibly ecologically—very similar indigenous American (Sambucus canadensis) and European (S. nigra) species.

The number of non-native taxa maintained by food foresters, 240, was 41 percent greater than the number of native taxa, 170. Apple (Malus domestica) was the most common non-native species, found at 11 of the 17 sites. Two additional fruit tree species, peach (Prunus persica) and plum (Prunus domestica) were identified in 10 food forests. Comfrey (Symphytum sp.), a plant frequently promoted by permaculturists as a ”dynamic accumulator of soil nutrients, was also found at 10 of the 17 sites.

Regardless of nativity, non-productive plants make up the majority of recorded plant taxa (57.8 percent), and native productive plants a small minority.(12.4 percent). Though these plants may not produce food or have a medicinal purpose, they may still function as resource plants for the productive plants, providing, for example, habitat for pollinators or insect predators.

Fruiting shrubs such as highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) represented almost half of the native productive taxa, though plants of hybrid parentage or uncertain provenance such as elderberry, blackberry (Rubus sp.), and raspberry (Rubus sp.) were categorized as native, potentially inflating the total number of native productive taxa.

Table 2. Distribution of unique plant taxa recorded from food forest sites (n=17) in the Northeast U.S., by plant type (native vs. non-native) and use.

|

Plant type/Use |

Total number of taxa |

Percent of total taxa |

|

Native |

170 |

41.5 |

|

Fruiting tree |

12 |

2.9 |

|

Fruiting shrub |

23 |

5.6 |

|

Other fruiting |

3 |

0.7 |

|

Nut tree |

5 |

1.2 |

|

Perennial vegetable |

4 |

1.0 |

|

Perennial herb |

8 |

1.0 |

|

Other herbaceous perennial |

75 |

18.3 |

|

Other nonproductive |

40 |

9.8 |

|

Non-native |

240 |

58.5 |

|

Fruiting tree |

20 |

4.9 |

|

Fruiting shrub |

19 |

4.6 |

|

Other fruiting |

4 |

1.0 |

|

Nut tree |

5 |

1.2 |

|

Perennial vegetable |

7 |

1.7 |

|

Perennial herb |

35 |

8.5 |

|

Annual vegetable |

37 |

9 |

|

Annual herb |

11 |

2.7 |

|

Other herbaceous perennial |

35 |

8.5 |

|

Other nonproductive |

87 |

21.2 |

Soil Analysis Results

The average percent soil organic matter (SOM) for the 17 sites, 7.58 percent, was considerably higher than the 2 to 3 percent SOM typically found in in loam soils in the Northeast U.S. (Magdoff & Van Es, 2021), indicating that the soils had been enriched with organic matter, most likely in the form of compost, applied either at the time of establishment or as a top dressing after planting, or mulches such as woodchips. At 154 mg kg-1, the average phosphorus level for food forest soils was considerably higher than that required for optimal crop growth (30-50 mg kg-1). Phosphorus and SOM levels, however, were considerably lower than those for adjacent annual agroecosystems (7.58 vs. 15.75 percent for SOM and 154 mg kg-1 vs 257 mg kg-1 for phosphorus). Annual vegetables in urban areas are frequently grown in technosols (media constructed from compost, soil, and other materials) with high levels of organic matter and phosphorus in cap-and-fill systems to obviate the problem of soil contamination (Ugarte & Taylor, 2020). The deeper rooting depth of woody perennial plants precludes the use of these systems in food forestry, hence the lower levels of SOM and phosphorus observed for food forest soils in this study. These lower soil phosphorus levels may reduce the potential negative impact of food forests on stormwater quality compared to annual production, in which excessive use of compost may contribute to nutrient loading of stormwater and groundwater (Small et al., 2019).

Table 3. Soil analysis results for food forest sites (n=17) in the Northeast U.S. and adjacent annual production sites and lawn areas

|

Food Forest |

Annual Production |

Lawn |

|

|

pH |

6.13 +/- 0.6 |

6.31 +/- 0.4 |

6.18 +/- 0.7 |

|

Soil organic matter (%) |

7.58 +/- 0.3 |

15.75 +/- 8.5 |

6.83 +/- 4.4 |

|

Available P (mg/kg) |

154.32 +/- 76.9 |

256.97 +/- 133.6 |

127.74 +/- 55 |

|

Exchangeable CA (mg/kg) |

2511.57 +/- 1203.2 |

3562.41 +/- 1507.5 |

2422.98 +/- 1136.0 |

|

Exchangeable Mg (mg/kg) |

196.21 +/- 90.3 |

378.75 +/- 159.71 |

179.94 +/- 96.2 |

|

Zn (mg/kg) |

27.11 +/- 23.7 |

28.95 +/- 17.4 |

22.82 +/- 24.2 |

+/- one standard deviation

References

Magdoff, F., & Van Es, H. (2021). Building soils for better crops: Ecological management for healthy soils. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program.

Small, G., Shrestha, P., Metson, G. S., Polsky, K., Jimenez, I., & Kay, A. (2019). Excess phosphorus from compost applications in urban gardens creates potential pollution hotspots. Environmental Research Communications, 1(9), 091007.

Ugarte, C. M., & Taylor, J. R. (2020). Chemical and biological indicators of soil health in Chicago urban gardens and farms. Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems, 5(1), e20004.

The purpose of this research project was to advance the understanding and application of urban agroforestry (UAF) systems in the northeastern United States, with a focus on the use and perception of native productive plants within these multifunctional landscapes. The project aimed to analyze current knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding UAF among urban agriculturists and green industry professionals, identify barriers to adoption, explore how practitioners balance ecological and productive functions, and assess correlations between native plant inclusion and ecological quality.

To meet these objectives, the study employed a mixed-methods approach that included a quantitative online survey of gardeners, farmers, landscapers, and nursery professionals, as well as qualitative, semi-structured interviews and ecological site surveys. The survey gathered broad data on participants’ familiarity and attitudes toward UAF systems, native plants and ecological sustainability, while the interviews provided in-depth insight into motivations, tradeoffs, and site-level practices among active food foresters.

Results revealed that while awareness of native plants and their ecological benefits is generally high among green industry professionals, UAF systems remain relatively uncommon. Practitioners cited motivations such as community engagement, food security, biodiversity enhancement, and sustainability, but also reported challenges including invasive species management, limited space, and a lack of knowledge about UAF design and function. Interviews further highlighted the importance of cultural traditions, adaptability, and educational value within these systems, highlighting their ecological and social benefits.

The small number of respondents participating in UAF indicates these are not yet common practice. This could be due to lack of research on the productivity of these systems. There may also be barriers to including practices that provide habitat benefits as there is currently no monetary value associated with these ecological benefits. Further research as well as funding opportunities to provide payment for ecosystem services may help increase these practices within agricultural landscapes.

Overall, the project objectives were successfully met by characterizing stakeholder (landscape and nursery professionals) perceptions, identifying barriers to UAF practices, and documenting the social and ecological functions of existing UAF sites. Findings demonstrate that integrating native productive species into urban landscapes can enhance ecological quality and community resilience, while also revealing the need for greater outreach, education, and market development to support wider implementation of UAF practices.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Results of this project will be utilized in various academic, public, and professional outreach materials. The project results will produce at least three separate academic publications, including the results of the quantitative survey, the qualitative interviews, and the ecological surveys. Knowledge on UAF and native productive plants gained from surveys and interviews will be used to develop educational materials for gardeners and homeowners, as well as to formulate recommendations for green industry professionals to further expand the market for plants used in UAF systems, including native productive plants. Resources will include:

- Short publications on particularly promising native productive species and design strategies that feature native productive plants to be compiled and distributed digitally using the same avenues as the online survey distribution;

- Webinars for gardeners and agroforestry practitioners with information on how to include native productive plants in the landscape; and

- Lists of recommended native productive plants to be shared with nursery and landscape professionals.

Project Outcomes

My project aimed to identify barriers to the development of urban agroforests and identify models for ecologically sustainable agroforests incorporating native, productive plants. The resulting expansion of urban agroforestry could help:

- Conserve native biodiversity in urban areas and as a result provide ecosystem services to surrounding communities;

- Increase urban food security and community resilience;

- Contribute to growth in the nursery industry and economically benefit farmers by creating a new market for native productive plants;

- Improve access to nature and green spaces for urban communities;

- Promote mental health and wellbeing for residents through restorative urban landscapes attentive to their psychological needs; and

- Improve sense of place and belonging.

My project aimed to achieve these goals by:

- Characterizing urban agriculturalists’ and green industry professionals’ use, knowledge, and perceptions of urban agroforestry and native productive plants.

- Giving us a better understanding of the ecological and productivity tradeoffs associated with incorporating a greater number of native perennial plants into urban agroforestry systems.

- Identifying landscape designs that maximize ecological, productive, and cultural benefits.

- Identifying barriers to more widespread adoption of native productive plants and urban agroforestry systems.

- Generating publications including both scholarly articles and resources for lay audiences. (Upcoming)

During the course of this project I became more knowledgeable in urban agroforestry practices, especially those involving native plants. Through interviews with private and community agroforesters I learned how these systems can help support both families and the wider community. I am hopeful to see how local sustainable agriculture practices can help individuals, families, and communities feel more empowered to have some control over their food supply during difficult times. I learned various benefits and barriers to sustainable urban agriculture, especially with regard to using native plants within these systems. Due to the current state of the political climate, I am unsure of the future direction for my career or research, but I do hope to use the skills and knowledge gained during this project to make positive changes locally for my own family and community.