Progress report for GNE24-325

Project Information

In West Virginia (WV), pasture is a top agricultural commodity. Our systematic dung beetle sampling across 36 farms in 2022 and 2023 revealed that the majority of pastures in WV have low dung beetle abundances. Dung beetles play a crucial role in dung decomposition, increasing nutrient cycling and soil quality, and contribute to pest control. These insects can increase the sustainability of pasture agriculture. Dwindling dung beetle populations pose a significant challenge to farmers, leading to reduced pasture quality and livestock health. Farmers are reaching out to WVU entomologists for information on native dung beetle species and methods to restore their populations. In the United States, we do not have methods for breeding native dung beetles that can be easily adopted by farmers. Therefore, our project aims to address this by focusing on breeding dung beetles on a large scale. We will test two different methods of building outdoor nurseries to breed three different local dung beetle species. To identify the best method for each species, we will measure adult beetle production and conduct a cost analysis to determine the most affordable and efficient method for rearing the three species. Our goal is to develop and share successful methods by participating in podcasts, workshops, and field days and advocate for their adoption across the Northeastern United States.

Project Objective: Develop and compare two distinct low-cost methods for creating dung beetle nurseries suitable for West Virginia farms:

Our goal for this project is to compare two rearing methods for three species of locally abundant dung beetle and understand the maximum beetle output from these rearing methods, and the relative costs of each method per beetle. We will measure 1) the rate at which beetles reproduce in each nursery type, 2) the maximum stable population for each nursery type, and the 3) cost of building and maintaining each nursery type.

We will compare “bin nurseries'' and “frame nurseries”. Bin nurseries will use a standardized potting media mixed with sand in a plastic 30-gal container that can be easily moved in and out of shelter depending on the weather conditions and during the release of the new beetles to a pasture. Frame nurseries will be built from a 1m2 wooden frame with an insect mesh cover placed in-situ onto pasture soil. These methods have been developed by modifying established large-scale dung beetle breeding methods used by companies in Australia and New Zealand.

Because they are larger, we hypothesize that frame nurseries will produce more beetles and will be lower cost to build than bin nurseries but may show more variability in production or even fail. We expect bin nurseries will show less variability in beetle production because they will be less susceptible to weather and soil conditions.

To achieve this objective, we will:

- Establish dung beetle breeding nurseries.

- Assess dung beetle emergence rates and abundance for three different native dung beetle species.

- Quantify the cost-effectiveness of the developed methods.

The purpose of this project is to address the pressing need for sustainable solutions to improving nutrient cycling and pasture health in grazing agriculture, by focusing on developing methods that can, in the future, enhance dung beetle populations to improve ecosystem health and farm productivity.

Dung beetle activity significantly influences soil health and GHG (GreenHouse Gas) emissions, by improving soil structure, soil nutrient availability, water infiltration and carbon sequestration (Nichols et al., 2008). These detritivores reduce GHGs such as nitrous oxide and methane, underscoring their importance in climate-smart agriculture (Slade & Roslin, 2016).

Dung beetle populations are under threat due to climate change and intensifying agriculture (Hutton & Giller, 2003; Leandro Rivel & Vaz-de-Mello, 2023). The use of broad-spectrum insecticides decrease their reproduction rates (Jacobs & Scholtz, 2015), and increased carbon dioxide levels are reducing their size and survival rates. Declining dung beetle populations present a major hurdle for farmers as they risk losing essential ecosystem benefits supplied by these insects. By developing practical solutions for dung beetle rearing, our project aims to enhance agricultural sustainability and resilience aligning with the overarching goals of Northeast SARE to promote accessible and sustainable agriculture.

Northeastern farmers, and particularly West Virginia livestock producers need additional tools to build dung beetle populations. There is a demonstrated need to develop native dung beetle rearing practices for the Northeastern US pastures to restore their populations and enhance ecosystem services they provide. In 2022 and 2023, we surveyed dung beetles in pastures across WV, and found significant variation in their abundance. Further, we have received emails and calls from producers interested in enhancing dung beetle populations, but who lack effective strategies beyond reducing the use of livestock dewormers. Previous research has largely focused on the negative effects of anti-parasitic drugs on dung beetles (Finch et al., 2020; Lumaret et al., 2012). While reducing dewormer use may help populations recover, this process can be slow. A farmer from Hampshire county, WV, reached out to us in 2022, because her new farm had low dung beetle populations due to historic livestock treatments. She was looking for information about native dung beetles and alternative ways to restore their populations and for where to purchase them. To our knowledge, only two small suppliers in the US in Texas and Florida, sell a mixture of introduced and native species for approximately $1/beetle. This shows that rearing locally adapted dung beetles is attractive to some producers, will offer an additional method for increasing populations, and may even provide some with additional income.

Our project seeks to develop reliable and accessible methods for dung beetle rearing, tailored to Northeastern dung beetle communities. We will test on-farm methods for building nurseries. Through this grant, we aim to develop practical and cost-effective methods for rearing dung beetles at scale to address the current deficit in strategies for increasing beetle populations.

We will develop rearing methods for three important species of dung beetles. Several families of dung beetles, including Scarabaeidae, Geotrupidae, Histeridae, Hydrophilidae, and Staphylinidae aid in dung pat degradation and nutrient redistribution and reduce parasites on pastures. For this project, we have selected three species that are locally abundant and exhibit three different behaviors, providing different services to pasture ecosystems.

- Onthophagus hecate: medium-sized dung beetle that creates brood balls from dung and tunnels them deep into the soil; Tunneler dung beetles increase nutrient incorporation into the soil and alter soil structure, which benefits pastures (Nichols et al., 2008; Bertone et al., 2005).

- Sphaeridium lunatum: medium-sized predatory dung beetle that increases pat decomposition and feeds on maggots of flies that are dangerous to livestock (Holter, 2004; Abdel-Gawaad et al., 1976).

- Oscarinus rusicola: a small, highly fecund dung beetle that creates brood balls within dung pats. Dweller species accelerate dung decomposition (Wall & Strong, 1987).

The rationale for this project is to find practical ways to increase low dung beetle populations, and thus increase the valuable ecosystem services they provide to pasture agriculture. Our aim is to provide new tools for building diverse pasture ecosystem communities, contributing to the long-term sustainability of US agriculture. These methods will have broad applications across the Eastern US and beyond, as these species are found widely east of the Rocky Mountains. Ultimately, with the help of this project and collaborative efforts with farmers, researchers, and stakeholders, we envision scaling up successful dung beetle rearing methods to benefit agricultural communities across the Northeastern US.

Research

Project Objective: Develop and standardize two distinct low-cost methods for creating dung beetle breeding nurseries suitable for West Virginia farms.

1) Establish dung beetle breeding nurseries:

1.1 Collect seed populations of dung beetles.

To establish dung beetle breeding nurseries, we will collect 300 (50 for each nursery) beetles of each species. We will collect live individuals of our three candidate species (Onthophagus hecate (OH), Oscarinus rusicola (OR) and Sphaeridium lunatum (SL)) during Spring and Summer of 2025, from nearby WVU Research, Education, and Outreach Centers (REOCs) - West Virginia University Animal Science REOC , J.W. Ruby REOC, WVU Agronomy REOC and Organic REOC. From our monitoring conducted in the same farms in 2022, we have identified that these farms have abundant populations of the candidate species.

To collect beetles, we will use standard live dung beetle trapping methods including dung-baited pitfalls (without a killing-agent) and poop “bombs” (dung balls wrapped in cheesecloth). We have found that these poop bombs were able to trap small dwelling species, like OR. We will also perform hand collection by exploring natural dung pats. The live beetles collected will be stored temporarily in the WVU Insect Agroecology lab.

1.2 Build the nurseries

Our in-farm, low-cost methods will be tested at the WVU Animal Sciences Research Education and Outreach Center (REOC) in Morgantown, WV. To have a steady supply of dung to feed our dung beetle nurseries, we will keep 5 stocker cows that are not chemically treated on this farm, and collect dung exclusively from their paddock.

The bin nursery will be tested and developed for the purpose of moving it around a farm during dung feeding and during the release of the young beetles to a paddock. The bin nursery will be built using a 30-gal clear storage box, which will be filled with a mixture of sand and potting soil in a 2:1 ratio. We will also fill the bin with a few pieces of cardboard or bark, to serve as a hiding/shelter spot for our adult beetles. The bin nurseries will be covered with a fine insect mesh for ventilation and kept in a sheltered place inside the barn.

The frame nurseries will be built by creating a 1m2 frame made with untreated wood 2in x 6in x 1 m boards. This frame will be inserted into the soil and covered with a ventilated roof made with fine insect mesh. The frames will mimic natural breeding of the beetles in soil and so the frames will be kept at least 50 m apart.

Both nursery types will be replicated 3 times in June and August of 2025 and 2026 (18 frame nurseries = 3 replicates x 3 species x 2 time periods). In total, we will have 36 different nursery setups each year (18 bin + 18 frame). Nurseries will be monitored for 1 year to measure maximum beetle reproductive output and overwintering survival.

Each of the nurseries will be established based on the species: 1) OH is currently reared in our lab at WVU and they can be easily sexed out because the males have cephalic horns. We will release 50 OH individuals in each nursery in a 3 male:5 female sex ratio. 2) OR is also reared in our lab, they are smaller beetles and sex cannot easily be distinguished in live beetles. We will, therefore, add 50 OR unsexed individuals in each nursery. 3) SL will be reared like OR: 50 of these beetles will be added into every nursery (beetles in Sphaeridium genus reared in (Abdel-Gawaad et al.,1976). Because we need to distinguish between the initial/parent population of beetles that will be placed at the start of each nursery and their offspring, we will mark the initial beetles on their elytra using a dental drill (Wuerges & Hernández, 2020). All nurseries will be ‘fed’ with 3 pats of 500g of fresh dung every 2 weeks.

2) Assess dung beetle emergence rates and abundance for three different native dung beetle species

To test the efficacy of these nurseries we will estimate adult beetle populations. To measure the active, adult beetle populations, we will set a dung-baited pitfall trap, without a killing agent for 24 h inside each of these bin and frame nurseries immediately before three manure pats are added (first 24h and then every 2 weeks subsequently). We will do this in the 24 h before adding manure to ensure that adult beetle populations are actively looking for a new source of dung. We will set two of these traps in two corners of the nursery with minimum disturbance. After 24 hours of setting the trap, we will make note of the number of individuals collected and note those from the initial, parental population (marked). Because we are unlikely to recover all dung beetles in the nurseries using pitfall traps, we will estimate the capture rate of dung beetles, we will estimate recapture of our initial population in the first 24 hours. While we still have the initial populations of beetles, we will also use the Lincoln-Petersen estimator formula to estimate the population size of releasable beetles (N =(M * C) / R), where: M is the total number of marked beetles released initially, C is the total number of beetles captured during the recapture effort and R is the number of marked beetles recaptured during the recapture effort. We will continue to sample every 2 weeks through the autumn until we are no longer catching beetles in pitfall traps, when we will assume they have started overwintering. We will restart sampling in March.

At the end of one year, we will have recorded data on the active number of adults every 2 weeks for each nursery, and can calculate the population growth rate and generation initial time of each nursery type for each species. Over time, we expect that each nursery will reach a maximum number of beetles based on available manure and space. We are expecting the frame nursery to have a larger number of releasable beetles, as it has the benefit of having more space for the beetles to breed in the farm’s soil than in the media of bin nursery. However, the bin nursery can be controlled better and is easily portable. We will use a Repeated Measures Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a negative binomial error distribution to determine the effects of nursery type and time on each of our species. We will use a Tukey post hoc test to compare our results between species within each nursery type and between nursery types for each species.

Potential pitfalls: We may encounter difficulty if one of these species is not amenable to rearing in either a bin nursery or in a frame nursery. However, we are currently successfully rearing 2 of the 3 species in the lab in similar conditions to the bin nurseries and the 3rd species, SL, has been successfully reared elsewhere (Abdel-Gawaad et al., 1976) and is found ubiquitously in dung pats and pitfall traps in WV. If we are unable to rear one of these species in year 1, we will substitute Onthophagus taurus, an introduced, but highly successful dung beetle that is known to provide ecosystem services across much of the Eastern United States.

3) Quantify the cost-effectiveness of the developed methods

We will identify and quantify cost components of both nursery types which will include the cost of all materials used, the labor for setting up and maintaining each nursery type over duration of the study, and the frequency of nursery management tasks. This will include the time and money spent on collecting dung and live beetles. From the number of releasable beetles calculated in step 2, we can calculate the cost per beetle emerged for each species from each nursery type. The most cost-effective method for rearing each native species will be the nursery type that yields the highest number of releasable beetles at the lowest cost per beetle. We will use 2-way ANOVA to determine if there are significant differences in cost-effectiveness between nursery types for each species.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

We will disseminate our project information to diverse stakeholders through the following outreach activities. Our overall goal is to share the successful rearing methods and advocate for their adoption across West Virginia and the North East United States to enhance native dung beetle populations and promote regenerative agriculture.

- One open-access peer-reviewed publication of the results of our dung beetle rearing methods in a scientific journal. We will target open-access journals with which WVU partners to eliminate open-access publication fees. We are committed to open science that reduces access barriers for our stakeholders.

- Podcast Collaboration with Mountaineer Farm Talk: We will contribute to a podcast series (Mountaineer Farm Talk) dedicated to discussing the project objectives, methods, and preliminary findings. We will highlight the importance of dung beetles in agriculture and the potential benefits of dung beetle nurseries. We will discuss the practical aspects of setting up and managing dung beetle nurseries on farms. Target Audience: Farmers, agricultural professionals, and anyone interested in sustainable farming practices.

- Talk at the Appalachian Cattlemen's Association: We will deliver a presentation at a meeting or conference organized by the Appalachian Cattlemen's Association. We will share insights from the project, including the development of dung beetle nurseries and their potential impact on pasture health and livestock management. We will address questions and concerns from attendees, fostering engagement and discussion. Target Audience: Cattle farmers, ranchers, and members of the Appalachian Cattlemen's Association.

- Extension Publication and information on Rowen Agroecology Lab Website: We write an extension publication detailing the step-by-step process of establishing and maintaining dung beetle nurseries on farms. Include information on dung beetle identification, nursery construction, management practices, and the benefits of incorporating dung beetles into farming systems. We will create a dedicated section on the Rowen lab website to host project information, updates, and resources related to dung beetle nurseries, including links to a YouTube video and an extension publication. Target Audience: Farmers, extension agents, agricultural educators, 4H students, and researchers interested in sustainable agriculture.

- Guide Preparation: We will develop a comprehensive guidebook that serves as a practical manual for farmers interested in implementing dung beetle nurseries. This will include detailed instructions on dung beetle identification, selection of suitable nursery sites, construction of nurseries, and ongoing management practices. We will highlight the ecological benefits of dung beetles and how they contribute to soil health, nutrient cycling, and pest control. Target Audience: Farmers, agricultural consultants, extension agents, and educators seeking practical guidance on dung beetle conservation and management.

- Set up an exhibit and participate at Organic Field Day, 2025 & 2026: We will join faculty, staff and students from the WVU Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design and WVU Extension Service for the Organic Field Day in 2025 & 2026. Here we will set up an exhibit and poster (by our Undergraduate Project Assistant) to present our project results to the general public including organic farmers, home gardeners and anyone interested in learning more about raising dung beetles.

Project Outcomes

Future sustainability and benefits to farmers:

For farmers, instead of relying solely on purchasing introduced dung beetle species from breeders—often at high costs—farmers can adopt the in-farm nursery method developed through this project. With limited resources, they can establish small-scale breeding setups and even explore entrepreneurial opportunities by not just selling dung beetles but also the nursery components to others, creating an additional revenue stream.

On their farms, thriving dung beetle populations will reduce reliance on dewormers and other chemicals. The presence of active dung beetles accelerates manure degradation, minimizing pasture fouling and reducing forage loss. Over time, this leads to fewer pests, improved soil aeration, and enhanced nutrient cycling, all of which significantly support the principles of regenerative agriculture.

I have also been able to train and mentor two undergraduate students in North American dung beetle taxonomy and spread awareness about the critical role of conserving native and local dung beetle species in West Virginia. I plan to mentor at least one more student. By working directly with these students on fieldwork—encompassing trapping, hand collection, and breeding methods—this project ensures that knowledge about the importance of beneficial insects in agroecosystems is disseminated and that motivation to conserve these species continues to grow.

Preliminary data analysis:

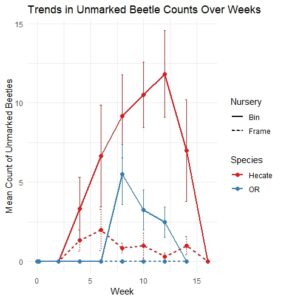

To assess the impact of Species and Nursery types on the count of unmarked (new progeny) beetles, a two-way ANOVA was conducted.

- OR vs. Hecate: Hecate showed higher beetle counts than OR(diff = -2.4767, p-value = 5.8e-06). Hecate larvae

- The species SL were unable to breed in the nurseries.

- Frames vs. Bins: Beetle counts in Bins were significantly higher than in Frames(diff = -3.0795, p-value = 0).

New progeny (OR species) - First appearance of progeny was at week 4 for OH and week 6 for OR.

Trends in the new progeny between 2 nursery types and 2 species

Next steps:

- The species SL will be replaced by Onthophagus taurus, a species that is common in our area and has been successfully bred elsewhere; we can compare its performance with the native and local species, Hecate and OR, to see how well they fare under the different nursery conditions (Frame vs. Bin).

- Temperature sensors will be incorporated to evaluate the relationship between temperature and progeny production.

- I will use a Repeated Measures Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a negative binomial error distribution to determine the effects of nursery type and time on each of our species. This model will allow for the assessment of both week-to-week variations and time periods (early vs. late study phases) in beetle counts, along with the interaction effects between Species, Nursery types, and Week.

- To control temperature fluctuations, beetles will be kept in bins inside the lab, rather than in the barn.

I had the opportunity to mentor two undergraduate students (Mentoring UG students) in dung beetle taxonomy, pinning and preservation. I experimented with various materials to find durable and cost-effective options for constructing the nurseries (Building frame nurseries). I developed practical skills like carpentry, driving, managing expenses, and creating purchase orders and receipts. Extensive hand-sampling for the starter population of Onthophagus hecate, Otophorus haemorrhoidalis and Sphaeridium lunatum taught me how scarce these beetles are and highlighted the challenges farmers may face in sourcing an initial population for breeding. This underscored the importance of establishing large-scale breeding setups and building networks with nearby farmers who can share local/native dung beetles.

As this type of experiment had not been conducted before on these specific species and at this scale, I gained numerous insights along the way. For example, I learned how to make small markings on beetles using size-zero insect pins (A marked O.hecate), the appropriate quantity of dung needed to feed them, and the moisture or water content required to support their growth and reproduction.

Additionally, I observed that Onthophagus hecate and Otophorus haemorrhoidalis bred in nurseries were smaller in size compared to their wild counterparts.

This project has left me feeling optimistic about the future of implementing such nurseries at farm-level scales (on farm-site frame nurseries)(a bin nursery). If I could manage to do this with zero prior carpentry skills, no driving experience, and limited knowledge of the market for supplies and tools, I believe that interested farmers could also take up this project successfully. They have the potential to rear native or local dung beetles and make a positive impact.

As for my future career and research direction, I aim to work in the agricultural sciences and outreach sector, as well as in graduate education management. I am deeply passionate about communicating science to advance sustainable agriculture and ensuring graduate students have the support they need to pursue science.