Final report for GS18-187

Project Information

Farmers' markets play an important role within a sustainable agriculture system, connecting community, place, food networks, farmers, and economic development. Since 1994 the number of farmers' markets has grown dramatically, increasing by 490%. However, many farmers' markets fail, and it is not clear why. This proposal addresses this gap in our knowledge. For such an important resource, little is known concerning: How does farmers' market leadership influence factors contributing to success and failure? This research project documents the growth or contraction of farmers' markets in Virginia, uncovers patterns or trends contributing to the success and failure, aligns these findings through seven lenses for analyzing leadership and social enterprises, and disseminates these research findings. The outcomes of this research will provide valuable insights on building sustainable farmers' markets, thus creating more resilience for a sustainable agriculture system. These findings can help inform planning of future resources, such as mobile farmers' markets as well as identify recommendations for farmers' markets in decline. Community stakeholders, local food movements, and small farmers benefit. Understanding how leadership influences farmers' markets will lead to improved profitability of farmers/ranchers and enhance the quality of life for farmers, ranchers, and rural communities. Although these findings are specific to Virginia, the research may have broader implications for similar geographical regions and states.

As a result of this project, the following will have occurred:

- Documented growth or contraction of Farmers' Markets in Virginia;

- Uncovered patterns or trends in the variables contributing to success or decline of FMs;

- Aligned FM variables with the lenses for analyzing leadership and social enterprises; and

- Built Capacity for future research and practice.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

This study used a qualitative case study approach to guide the exploration of farmers market leadership. The purpose of this research was to study the influences of leadership on Virginia farmers' markets to better understand factors contributing to their success and failure. The case study approach helped to illustrate and illuminate the complexity of the influences of leadership. “A case study is a good approach when the inquirer has clearly identifiable cases with boundaries and seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of the cases or a comparison of several cases” (Cresswell & Poth, 2018, p. 100).

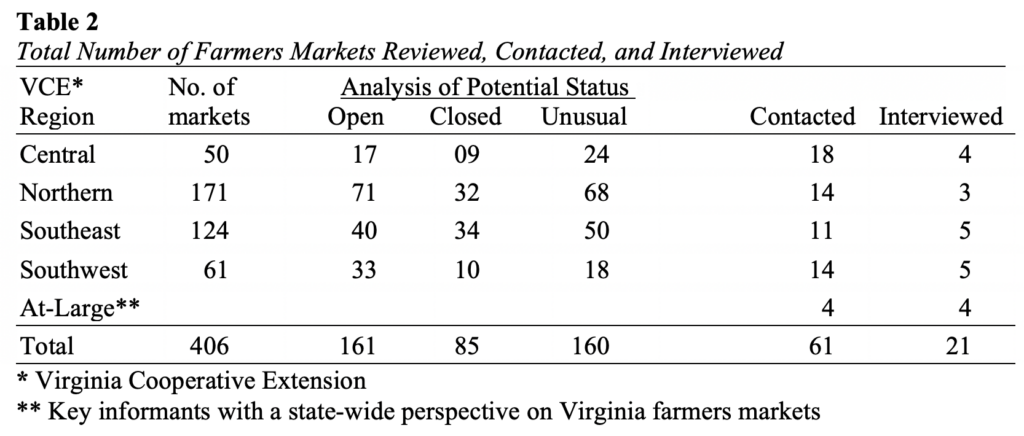

The population for this study included people involved in leading farmers market initiatives in Virginia. Multiple online listings provided a basis for creating a master list of Virginia farmers markets (Table 1). In fall 2020, using an IRB-approved recruitment message (Appendix-A-Recruitment-Email-Sample-SSARE.pdf), the researcher emailed the listed contacts for twenty markets, five markets from each region. This effort yielded no volunteers for interviews.

Recruiting participants proved challenging, particularly for closed markets. The coronavirus pandemic also contributed to recruitment challenges in the fall of 2020 as farmers markets struggled to remain open, provide operational alternatives to walking through the markets, and meet Virginia’s mandates for operating non-essential businesses. Recruitment resumed in March 2021. While continuing to recruit from potentially closed markets by email and phone (Appendix-B-Recruitment-Phone-Sample-Script-SSARE.pdf), the researcher began recruiting contacts associated with markets known to be in operation.

The recruitment email requested interested parties respond directly to the researcher by email or phone. These individuals received a follow-up email, which included an informed consent sheet (Appendix-C-Informed-Consent-Sheet-SSARE.pdf), W-9 tax form for remuneration, and an invitation to schedule a time to talk. During interviews, key informants provided additional contacts for Virginia farmers market leadership perspectives; this snowball sampling yielded additional recruitment opportunities and generated four additional key informants with state-wide knowledge (rather than localized).

Data collection followed a semi-structured interview protocol, which was pilot-tested and modified to incorporate feedback (Appendix-D-Interview-Protocol-SSARE.pdf). Jackson et al.’s (2018) Leadership Hexad provided the context for developing the prompts.

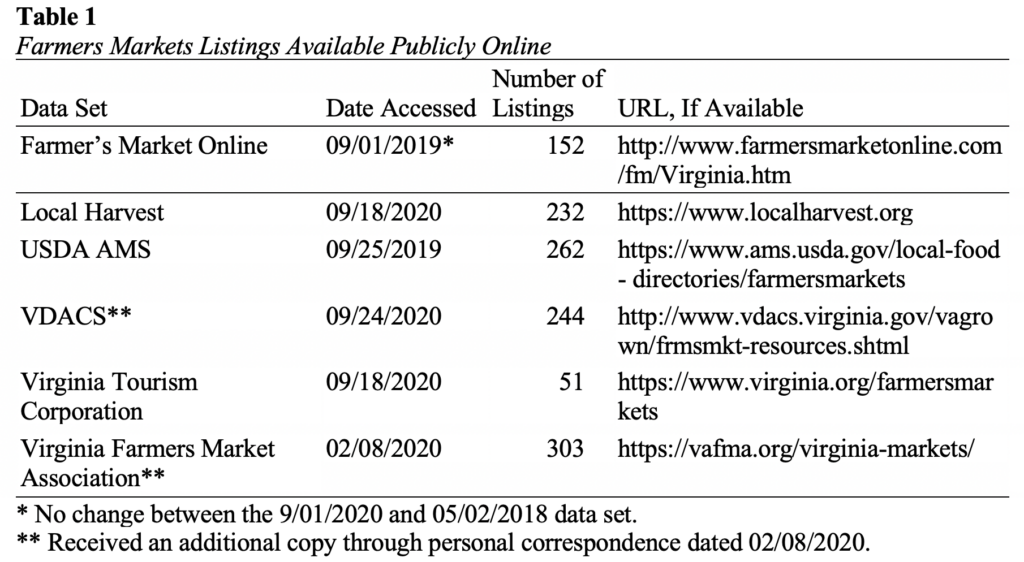

Twenty-one key informants were interviewed; they were associated with one closed market, sixteen active markets, and four organizations with state-wide perspectives about Virginia farmers markets (Table 2). Interviews were conducted over an eight-month period, across two farmers market seasons; six interviews were conducted between September 25 and November 11, 2020, and fifteen were conducted between March 05, 2021 and May 06, 2021.

The twenty-one farmers markets leaders provided in-depth perspectives on more than thirty-two Virginia farmers markets. More than half of the key informants had prior experience. Some participants had helped to lead multiple farmers markets in Virginia. Others provided state-wide perspectives regarding farmers markets and local food resources. Some interviewees provided insight from farmers market organizations, which provide leadership with multiple farmers markets.

Objective 1: The Growth or Contraction of Farmers Markets in Virginia

One of the objectives of this study was to gain a better understanding of the growth of farmers markets across Virginia. Getting an exact count of farmers markets can be challenging. One challenge relates to the temporary or impermanent nature of some farmers markets as they pop-up in parking lots and other locations. The global pandemic also contributed to challenges in gaining an exact count of farmers markets in Virginia: closure may be temporary or permanent. Multiple online listings provided a basis for creating a master list of Virginia farmers markets (Table 1): Local Harvest, Open Air, Virginia Farmers Market Association, Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and Virginia Department of Tourism.

Surging Operational Growth within the Farmers Market Itself

Many key informants in the study have noted an increase in market operations at their farmers market. Nearly half indicated the addition of an online ordering solution in the past year to accompany their web presence. Other key informants indicated an increase in their available hours, by adding a physical storefront or adding an additional market day, such as a Tuesday evening market. “We also launched what we’re calling the produce stand. We’re going to be selling through the week when the farmers aren’t here, a small selection of goods from our vendors” (KI-c). Some key informants indicated the addition of a winter market or extending their market from seasonal to year-round. Several key informants indicated the launch of entirely new markets. One participant described their new market as being typical in size: “It’s a very good example of a new market, one year old; it has ten vendors” (KI-p). By creating and maintaining these alternative access times and locations, farmers markets’ leaders have increased the direct-to-consumer options available in their community.

Objective 2: Uncover Patterns or Trends in the Variables Contributing to Success or Failure of Farmers Markets

Short Food Supply Chain

The short food supply chain (SFCF) includes a number of factors, such as economic development, cooperation, close geographic proximity, and social relations (Delicato et al. (2019; Feenstra & Hardesty, 2016; Franck et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2019); and key informants provided rich context around these topics. One key informant couched the purpose of their organization in local economic development terms: “The goal of the nonprofit is to provide our local economy, specifically our local agricultural economy, with a venue in order to make a living and sell their product” (KI-v). More than half of the key informants noted their markets had rules linked to geographic proximity. In some cases, rules restricted participation by the location of the vendor’s residence. Other rules limited the travel miles of the food itself. Some markets had rules linked to where the vendor resided as well as the travel distance of the food:

“Our rule is that the vendor has to be within 100 miles of the market to sell. With the exception of a couple of products, like seafood or roasted coffee, and we make exceptions for that on a case-by-case basis. But even then, you as the business owner, have to live within that 100-mile radius. And we do allow people to resell if all the product is from a 100-mile radius, and it's all labeled, so that the customer knows where it came from, and how it was grown.” (KI-m)

Many of the key informants described the social atmosphere and cooperative environment among those participating in the market. One key informant described their family-like market community, noting how learning and personal growth can occur as a result of relationships:

“One of the coolest things to watch and see is some of, what I would call my old fashion, older farmers who started with us who used to just grow beans, and tomatoes, and corn—the traditional kinds of things—and then having them interact with some of the other farmers. That's the thing. We truly created like a family community amongst our folks. And to me, that's very important. You're only as good as the vendor next to you. But anyway, [I get] to watch some of these older folks grow kohlrabi—and instead of just growing traditional eggplants, growing Japanese eggplants. And [they are] kind of expand[ing] their personal horizons, too.” (KI-r)

Another key informant, described their community as well as the general atmosphere and energy around their market:

“I feel like we're a little behind the curve in terms of the local food movement. But we're starting to get caught up, and there's a lot of new young farmers, and the energy that they bring to market, and the passion they bring, meshes with our mission really well. And they work cooperatively instead of acting like they're competing against each other, which I feel like is really important.” (KI-m)

Another aspect of the SFSC involves community connections and social relationships. Many key informants highlight the importance and value for the social relationships. One key informant sums up the social nature of their farmers market:

“The community comes out and sees it [the farmers market], and they see such a diversity of different types and different personalities, and you can find somebody that fits, like they can be your best friend at that market, basically. It's so many different aspects and personalities out there, and it's just like there's somebody for everybody. And there's a farmer for everybody.” (KI-0

Overall, participants reinforced the idea that SFSCs afford opportunities to work cooperatively toward community economic development and to build connections and relationships among the participants in the local food system.

Stabilizing Forces

Key informants noted the fragility of farmers markets as well as multiple factors critical to their success and failure. One interviewee observed a pattern of farmers markets opening and closing with little fanfare: “Yeah, there's so many [farmers markets] out there that are very fragile, and kind of just spring up, and die out, before a lot of people even know that they’re there” (KI-n). Another participant shared an insight about what can make a difference to a market:

“When you lose a key vendor, that can make a big difference. A lot of markets don't have a steady location, and so they've had to move several times. That can be a big issue. I guess stability—when you've got a stable location, and maybe a stable manager, and some amount of financial stability—I think all of that goes into it.” (KI-h)

These observations highlight market leaders’ concerns over stability in vendors, location, management, and financial support.

Permanency of Facilities

Multiple key informants talked about the uncertainty associated with short-term leases and the value of a permanent facility. One key informant noted the planning challenges and uncertainty associated with leasing the property on which the farmers market resides: “We're still currently just leasing land. And it's an issue every year when we try to renew. Because we can never get a longstanding lease for us to just feel comfortable where we're at. And [when we have a lease], we never have our own land so that we can actually develop to maximize the potential of the farmers market” (KI-n). Another participant described their site location as being donated, which could lead to challenges in the future:

“The downside to our location [is] we don't own the location. The location we've been in has been generously provided to us free of cost for years, but the man who owns it is not, of course, part of the [market].” (KI-u)

Other market leaders noted the value of having a pavilion or structure. One key informant described how their market fluctuated over the years. Having a designated facility may provide some consistency:

“There’s always kind of just been this, ‘it pops up for a few years, and then it dies down, and then it pops up and it dies down.’ This is probably the longest that we’ve had it. But again, we now have a designated facility for it.” (KI-d)

Temporary markets have a lot of flexibility, which can also lead to a lack of stabilility. One key informant, KI-f, told the story of a single market that changed names, locations, and management three years in a row. Most of the vendors moved with the market each time; eventually however, the market closed. Another key informant contrasted temporary versus permanent facilities from a public safety perspective:

“[One of the] considerations was public safety. And we're not just a farmers market that drops on a piece of property and goes away at the end of the day. This market is here year-round, and it stays on the property, even when we're not here. We maybe have one or two vendors that will use a tent, but for the most part, they're all under cover.” (KI-a)

In general, participants noted the value for farmers markets to have a stable location and facilities.

Municipal Support

Most of the key informants highlighted the value of municipal support in order to operate a farmers market in their community. This much needed support took many forms, such as permits, financial, and location support. While key informants at municipality-run markets did not foreground issues, most of the key informants who worked with 501(c)(3) and for-profit markets highlighted major challenges with the Virginia permitting process. One participant provided an example and suggestions to improve the Virginia system:

“When we talk about permits, I can write horror stories about getting a permit in Virginia… For example, we have a market in [a] county, and we have to navigate this weird fair permit. It's just for four months. And then, after that you have to renew it every month. And then if you go to [city], I think it's [called] an event permit, which is the same thing—a parade or a farmers market. It's not the same. And for each one, it’s like a different scenario. Just having a farmers markets permit in Virginia would help. You apply to that means you’re a farmers market, and you can apply in your county, but it's a farmers market permit.” (KI-p)

Key informants noted a second aspect of municipal support: financial. Many interviewees described their markets as losing money, or barely breaking even, each year. As one noted, “We go every year to our county administrators and put our hand out and ask for a little bit of money” (KI-v). Other than municipal support, other sources for offsetting the shortfalls included private donations, special fundraising events, and market day or annual sponsorships. Lastly, key informants noted that municipalities can also help or hinder efforts to find a location to hold a market. One key informant described how the lack of support from the local government made it difficult to find a location in their community to hold a market: “I would go to City Council meetings. ... After sitting in the meeting and them telling me, ‘Oh, we don’t think [our municipality] needs a market.’ I don’t think they wanted the market to be at all” (KI-e). In general, farmers market leaders noted the need for municipal support in order to help stabilize farmers markets in their community.

Objective 3: Align Farmers Markets Variables with the Lenses for Analyzing Leadership and Social Enterprises

The Leadership Hexad (Jackson et al., 2018) provides a means for exploring social enterprises through its six lenses: Person, Position, Process, Performance, Place, and Purpose. Relative to other entities, as well as amongst themselves, farmers markets are unique. As one key informant noted, “If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen one” (KI-t). Another key informant provides further context on farmers markets: “They're fragmented; they're not an organized, you know, business like a Walmart or something like that; they've got a business plan that’s—every one of them has got a different business plan, and that's what makes them unique” (KI-a). This section explores farmers markets within their unique context and through the six lenses of the Leadership Hexad.

Leadership through Person

The Person lens of the Leadership Hexad focuses on who has the informal power to create leadership within a farmers market (Jackson et al., 2018). While these findings about farmers markets leadership use a primary perspective of Person, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Person: choosing a market, needing a determined champion, and working in pairs.

Choosing a Market

Many of the market leaders highlighted the need to recruit and maintain vendors at their market, thus the vendors have informal power and influence on the performance of the market. In many instances, vendors have the option to choose whether to attend a market. One key informant described how vendors carefully assess their options before making that choice:

“[The vendors are] always on the prowl for a new market. They could give you some really good insight on the success and failure of a market, too... I just listened to some of the things they say, and how they answer me, and I can tell… They’re not too sure if they're going to be here next week. Because they're taking all these factors into consideration. And it's like real time.” (KI-j)

Part of the dilemma vendors face is whether a market will be profitable. From a farmers market perspective, the vendor/customer balance can lead to upward or downward spirals of attendance. Vendors are crucial to forming a successful market. One participant highlighted the importance of vendor consistency, especially for a new market: “In the early stages of a market, you have to have people who are willing to have some not-great sales days to hang in there... If a market is not consistent, you lose customers” (KI-h). Another key informant provided further context on the vendor/customer relationship and vendor preference for a well-established market:

“How long a market is around, pertains to its success… We barely have to request anyone to apply for our [established] market. Vendors try to get in, and they're, ‘Oh there's never an opening,’ because we always tend to favor return vendors. So, people, like the customers know—[this vegetable vendor] has been there for 30 years—they're a staple at that market. We give preference to people [vendors] like that, but that's not necessarily an ear marker of success for a market.” (KI-k)

In describing the importance of steady, strong, stable management at two struggling markets, one key informant’s remarks described the required trust and credibility with vendors, which other market leaders mentioned as well:

“In both cases, I had to go out and recruit vendors and say, ‘Look, trust me on this. This is a good market. It can do it. It'll be good for you. It'll be good, but you have to trust me.’ And that's what I had to do in the beginning...within two years, in both cases, you could see a huge difference, once the market had just some stable, steady, strong management.” (KI-g)

After these markets became established, this key informant noted, “In fact, I’ve had a waiting list the entire year” (KI-g). In general, key informants noted the decisions vendors make relative to choosing a market, or choosing to show up, have a direct impact on the market and its performance.

Needing a Determined Champion

More than half of the market leaders provided origin stories about their markets, which involved at least one champion. These champions differed in approach but share common characteristics: determined, committed, effective, and critical to the market’s initial success. As one participant noted, the market “was definitely dependent on that member that was driving the creation of it, and the success of it—that could see the vision of it, to see it come to fruition” (KI-j). Another informant described the commitments needed to create a farmers market. It involved a complicated and complex planning process with the county: “A retired planner with the county helped us to get through the initial requirements that they had as far as developing a plan” (KI-a). The interviewee described the end result as well worth the investment: plenty of parking, handicap accessible space with smooth surfaces, and bike racks, to name a few of the amenities included in the process. In contrast, one key informant provided background on a market without a strong champion:

“They never really formed an organization, and it struggled because of that... The woman that mainly ran it, sorta did it by herself... If you texted her, she just didn’t reply. [And, she] didn’t answer the phone. [The owner] hired somebody... The social media improved, but then it just—it didn’t have any momentum.” (KI-f)

The market without a strong champion eventually closed. Another key informant described the perseverance of some local business owners:

“Mainly it was a couple of ladies who had businesses in town just felt like it needed a farmers market. They held it together for about three years… We are talking about really determined people… I mean they were determined to hold down that corner…. Eventually, it was five pretty regular [vendors].” (KI-h)

After describing the transfer of management of a market in decline, one participant noted: “If it hadn't been bullheaded [by] me, taking the market, it probably would have closed for real” (KI-q). Based on the comments from the key informants, the overall sense is that determination and commitment were critical to the initial success of these farmers markets.

Working in Pairs

Two thirds of the interviewees strongly identified as working in a pair with another person. In many instances, they shared responsibilities with a spouse. When asked who manages the farmers market, one participant responded: “That’s me. My husband, sometimes he plays manager. We’re both always there. When the markets open, the two of us are always there on site” (KI-q). Another key informant noted sharing leadership with a spouse: “I’m the only official employee, but she and I share responsibilities. I couldn't do it without her, to be totally honest” (KI-u). Another participant describes how she and her partner make decisions related to the market: “With my husband and I doing this together, we’re together all the time, and so we have a lot of time and opportunity to talk through those kinds of things” (KI-r). One key informant described the importance of diverse styles and leveraging this diversity to distribute responsibilities. “[Another market leader] has written the grants, is kind of like the big picture, idea guy, and I am the ‘Okay, this is how we're actually going to implement this.’ Having that dynamic is really important” (KI-h). One interviewee, KI-v, described the value and utility of partnering with another person who has multiple roles: the founder of the farmers market, a volunteer to the market, and the representative to the nonprofit board that oversees the market. Another key informant described how pair of leaders who started the market used their influence to bring people into the planning process:

“Between the two of them, they had everyone on speed dial: they were really well connected with the Chamber, and they knew and had the mayor on speed dial, and the city manager on speed dial, and the president of [a large foundation] on speed dial. So, they were so well connected that they were able to bring all the people to the table.” (KI-l)

While key informants described other working relationships with individuals and small groups, the paired relationship occurred frequently when describing their farmers market leadership.

Leadership through Position

The Position lens of the Leadership Hexad focuses on who has the formal power to create leadership within a farmers market (Jackson et al., 2018). While these findings about farmers market leadership use a primary perspective of Position, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Position: becoming a community anchor and supporting entrepreneurship.

Becoming a Community Anchor

Multiple key informants got their start with farmers markets as vendors, which aligned with their personal values. For some market leaders, transitioning into the role of market manager was an act of service to others. One participant described how she transitioned to becoming a market manager:

“When the market was going to close, I’m looking around me, and [for] a lot of these people, this is their livelihood. It's not just a hobby for them [as it was for me]. It's their ‘bread and butter.’ And I’m thinking, ‘if this market closes, how do they survive? What's going to happen to them?’ And I couldn't just leave that on the table and walk away from it. Okay, well I’ll just, I’ll just make sure this is here for them, so they have this resource. And it just became bigger than me, really quickly.” (KI-q)

Other market managers were invited into the position by their municipality. When the former manager stepped down, one interviewee described her recruitment process: “They didn't even post the job. They knew me from when I was a vendor there; and they called me, and they were like, ‘Hey do you want to do this?,’ which I’m glad they did. And I mean, it's been awesome” (KI-o). Another market manager was recruited into the position because of ties to the community and previous experience with the farmers market: “The [municipality] started discussing with me the possibility of coming [into the farmers market position]… because I was already involved in the community. It was the community involvement that was the real connection” (KI-i). Another key informant summarized the value of having someone from the community take on the market manager role:

“What is really important in a manager is somebody who really knows their community and is passionate about what they're doing. And level of education and all of that stuff doesn’t matter a hill of beans if it's not something they really care about.” (KI-h)

In general, many key informants noted how market managers came into the position due to a connection or service to the community.

Supporting Entrepreneurship

Leadership through the lens of Position provides insight into how market leadership creates opportunities and supports entrepreneurship at their markets. This entrepreneurship can take many forms. In its simplest form, it can include providing a space for an information table that serves the community. As noted by several key informants, farmers as vendors do not always participate for a full season. One gives an example of how some farmers participate in the market: “They come in and sell their berries, and then they leave. They’re only there for four weeks” (KI-d). Another key informant expanded upon the seasonal nature of farmers as well as the purpose of their farmers market as a business accelerator.

“Farmers actually come and go. They kind of rotate in and out. The intention of [our farmers market], originally, was to let smaller businesses have an outlet to go direct to customer. But also to get their name out, for smaller businesses. So, we've seen farmers who have come to us, and had a very small business, but made connections, built their business, and now they're too big to even continue to come to our market, because they're too busy elsewhere and [with] other facilities. We want to be that. You start your business, you come to us, we help you accelerate your business to the point where you don't—not to say you don't stay here, [but] you outgrow us.” (KI-u)

Providing a supportive environment for entrepreneurship to occur does not necessarily mean that the vendor or farmer outgrows the farmers market. As one key informant describes, some vendors have built their business model around the market:

“A lot of them [the businesses] are either owned by the artisan or farmer themselves or [are] family-owned businesses. A lot of them really need the farmers market to sustain their business, because of the high profit margins on their items. They aren’t being undercut by wholesalers. So, it's really a place that has direct sales. But it's just like, they’ve built their whole business around it; and it's really the best way they can operate; and possibly, the only way they can operate and still maintain their business.” (KI-n)

The creation of online markets has opened up new opportunities for entrepreneurship. Not only does it create a new channel for farmers and vendors to make their goods available, market leadership can participate in the online markets as well. One participant provides further detail:

“The online market place has been great for someone who doesn't have the time to sit at a market for four hours, plus set up and break down. [My colleague] who manages the market also is a vendor. [And another colleague] is also a vendor. We're all very food-focused people and in multiple ways.” (KI-m)

As noted by some participants, the entrepreneurial nature of having online markets affords market leadership opportunities to participate in ways they could not before.

Leadership through Process

The leadership through Process lens focuses on how leadership happens within a farmers market (Jackson et al., 2018). Of all the lenses, leadership through Process is the one that is the most complicated and the least understood. While these findings about farmers markets leadership use a primary perspective of Process, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Process: owning a market and planning for succession.

Owning a Market

When talking about farmers markets, some key informants note the term “ownership” introduces ambiguity. What determines ownership? Is it the person or organization that coordinates and arranges for permits within the city or county in which the market resides? Coordinates insurance? Signs a land lease? Oftentimes, market leaders fall back on federal tax status to help distinguish the operations. An unknown tax exemption status for a farmers market can lead to confusion, as one participant noted: “There wasn’t any formal organization at all. It wasn’t an LLC. It wasn’t a nonprofit. It was just—I don’t even know how they got a bank account” (KI-f). Another key informant distills some of the confusion, bringing in a nonprofit perspective:

“It's hard to talk about ownership, with farmers markets, right? Because we manage the farmers markets, but basically ownership really depends on many things. We can own the farmers market in this neighborhood; but to operate it, we need the letter of support, so we can get the permits, right. So, in that case, we depend on the community so we can operate. [If] they say, ‘No,’ [then] it doesn't matter; we wouldn't be able to operate that market. So, we can own a market, and we can’t operate, in that case. So, we run all the farmers markets… [For a specific market], the county owns the market and they contract with us to manage it. It’s [our ourganization] a nonprofit, which helps us to bring grants and things for the operation.” (KI-p)

As noted above, some key informants used tax status as a means for typifying a farmers market.

Other key informants also noted the importance of tax status for acquiring grants. As a nonprofit, the federal tax exemption status assists in securing grants; however, grants are not as readily available for markets owned by a municipality, as another key informant notes:

“About grants and stuff, so, it’s hard because we are a municipal body; so a lot of grants that are open to nonprofits or LLCs or anything like that, we can’t even apply for. And I think that is part of the original reasoning for forming that [external] group, because they are actually a 501(c)(3). So, they can go after some of those grants, and kind of bring them into the market in a round-about way.” (KI-c)

Farmers markets can also use another federal tax exempt status, 501(c)(6), which is used by business leagues and chambers of commerce. This status affords farmers market leadership unique opportunities that would otherwise not be available, as one participant notes: “The 501(c)(6) [status] works really nicely; because if we were a 501(c)(3), the [municipality] wouldn't be able to do some of the things that they do for us” (KI-l).

Farmers Markets frequently operate under the umbrella of a 501(c)(3) sponsor. Each nonprofit sponsor has unique characteristics. One participant provides the following description of the nonprofit, which is the umbrella 501(c)(3) for their farmers market:

“And I know that [our nonprofit] would like to develop into sort of that kind of model, where we’re supporting agriculture throughout the county, not just at the market. And there’s a real impetus behind that, because the county wants to see that as well, as part of economic development. And so, there’s a lot of looking into how can [the] county support the farmers? And how can we support the farmers? And the farmers market is just one small component of that.” (KI-v)

Of the key informants that identified as having nonprofit farmers markets, the most common forms were the stand-alone 501(c)(3) and being under the umbrella of a 501(c)(3). Appendix H provides a visual representation of farmers markets and tax exemption status classification.

While not as common in Virginia as nonprofit or municipally sponsored markets (SNAP, 2019), private or for-profit farmers markets also operate in Virginia. The reasons for choosing private ownership are unique to the individuals and circumstances, yet several key informants distinguished their privately-owned markets as more vendor-focused. For example, one participant noted the following:

“All the other markets around me are government run. So, they have a very different take. We like to say they’re customer-centered markets, and we're a vendor centered market. So, it's my job to support the businesses that come to sell. It's their [the vendors’] job to take care of the customers.” (KI-q)

Some key informants described farmers markets that began as for-profit and then transitioned to another tax status. For example, on participant described their market’s history: “The farmers market started out as just a private entity... and [then] it became a program of Parks and Rec” (KI-n). Another key informant described an evolutionary process of creating a blended environment of for-profit and nonprofit functions in order to gain some advantages:

“A lot of farmers markets have gotten kind of creative, where they started off as a for-profit, and then they added a nonprofit to be sort of their umbrella agency … [For-profits] have to do things like pay rent… Some of them [farmers markets] are a weird mix or blend of nonprofit and for-profit.” (KI-l)

One participant affirmed how becoming a nonprofit has created new opportunities for the organization: “Now that we're officially a 501, I can actually do more. And I’ve researched more and bookmarked some [grant opportunities] for next year” (KI-o). Another participant shared how their nonprofit affiliation assists them with expenses: “We are not charged anything by Parks and Rec… They do not charge us rent. So that’s huge, because that can put an organization under—fast” (KI-g). In contrast, another key informant from a for-profit farmers market describes the interaction with the municipality: “Absolutely, I have to pay. I have to rent the lot [each week from the municipality]…We have 38 weeks of market each year” (KI-q). In general, key informants used tax exemption status to characterize the farmers market, especially talking about ownership and management.

Planning for Succession

Market leaders shared examples that involved planning for the future. Key informants noted multiple areas that would benefit from succession planning. These examples included location predictability, planning for operational growth, and planning for turnover.

Multiple markets described location predictability as an ongoing issue. This could be due to the lack of long-term leases or unexpected location shifts due to unforeseen instances. One key informant described the lack of predictable space, noting the uncertainty and difficulty in planning for the future:

“We're still currently just leasing land, and it's an issue every year, when we try to renew. Because we can never get a long-standing lease for us to just feel comfortable where we're at. And we never have our own land, so that we can actually develop to maximize the potential of the farmers market. That's something we've been struggling with, and try to get to the city council's ear, to try to make the farmers market a dedicated part of the city…. For the past two years, it's been kind of a headache just to wonder if they're actually going to try to renew our lease or not.” (KI-n)

While a pavilion or permanent structure was not a guarantee of a market success, markets with a permanent structure did not identify location predictability as an issue.

The second aspect of planning for succession involves the operational growth of individual markets. Nearly half of the key informants indicated their farmers markets have added a market day, such as Thursday; an online market; a home/office delivery service; a winter market; a new market; or some combination of the six. The operational growth has increased the organizational complexity, including increased employees and number of hours needed to run operations. One key informant noted how their market may need to find an alternative to being an association. While a 501(c)(3) sponsor has worked in the past, one key informant observed that as the market grows in complexity, it may need to become a stand-alone nonprofit:

“One is we would have to go out on our own, and no longer have a fiscal sponsor; which may, in fact, happen [anyway]. Only because of this year, we've gotten so complicated. We're running three markets now [normal, online, and winter]. So it doesn't make a whole lot of sense to have a fiscal sponsor as we have had. Any grants we write, we have to write through them, which is a whole complicated process.” (KI-g)

As KI-g noted above, grant-writing can be complicated when under the umbrella of another nonprofit. Another key informant described how changes to the market has opened up opportunities to bring new talent and skills to the farmers market:

“With the expansion into online ordering, and the second market, the time needed for that, really, was more than I could commit to the market. But in addition, my strength is not website development or online ordering. That was a component that I just wasn’t—didn't feel I had the strength. And we were also looking for someone who could assist us with grant prospecting. And so our [newly hired] assistant market manager has that background... with grant prospecting, and submitting grants.” (KI-v)

In summary, key informants have noted both the challenges and opportunities associated with the operational growth of their farmers markets.

The last area of succession planning relates to market manager turn-over and planning. One key informant describes the challenging conditions under which market managers must operate and why there is turnover:

“Working in food is so hard. It is relentless. Because the farmers wake up early, and people work late; and so it's—sometimes they have calls or things at night, or like seven, you never know, right… [You] have to wake up early, and you have to be outside in any condition. It could be cold; it could be rainy. It could be 90 degrees... Sometimes we have marketing managers that quit after two weeks: ‘I’m sorry. I didn't realize that.’ Because you go to a farmers market, and it’s so lovely; and you see a lot of people having fun; and once you've gone into management, it is not like that.” (KI-p)

This high turnover can have ramifications beyond the inconvenience of needing to hire another market manager. One key informant describes the impact of high turnover on the implementation and use of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at farmers markets:

“The lifespan of a market manager is relatively short, and turnover is a big issue. It's a big issue with SNAP, because there are all these permits and different things that are in people's names. And when one market manager disappears and takes the files, and then the new market manager doesn't know who the equipment provider is, or what the contract says [it’s a problem].” (KI-t)

The market manager turnover can affect some of the most fundamental market operations, such as communicating, branding, advertising, and earning media credit through webpages and social media accounts. One participant noted the importance of social media for managing a farmers market: “Whatever is on Facebook is what is real” (KI-j). At a fundamental level, access to communication channels affects the ability to update hours, answer questions, and manage a farmers market’s online presence.

Leadership through Performance

One of the more interesting aspects of the Leadership Hexad involves the flexibility of leadership through Performance. Grint's (2000) approach used the word results rather than performance. Within the social enterprise Leadership Hexad, changing the word to Performance embraces a broader and more nuanced understanding of leadership (Jackson et al., 2018). While these findings about farmers markets leadership use a primary perspective of Performance, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Performance. These findings include two themes that emerged from the data: surviving the initial phase of startup and choosing what gets measured—professionalizing market managers.

Surviving the Initial Phase of Startup

Several key informants described an initial period or startup phase in which a new farmers market struggles. One key informant spoke generally about the core elements needed in order to create a successful market:

“The different factors that play into whether a farmers market is going to be successful—of course, one of them is the right mix of vendors; the right mix of products; the right location; the right management team; and the right customers—and you’ve got to have all of those.” (KI-f)

In addition to having the right combination of factors, for a new market, market leaders suggest it takes two to five years to determine its viability. One key informant provides more context:

“You have to understand every market takes between like two to five years to actually really be a viable market. We like to say three years, to see really; and at the third year, we like to see projected upward growth for the market. And if we don't see that projected upward growth or maintaining a steady growth rate, then we have to evaluate whether or not it's worth having the market as part of our entity.” (KI-k)

While it may take two to five years to determine viability, other participants note how timing is critical along the way. One participant summarized the need to invest in equipment, promotion, outreach, and the need to build momentum in a very short period of time:

“Most of the time, markets fail because you don't have enough money to support your operations. And when you don't do enough investment to get good equipment, to get good promotion, and do outreach, and all these things that you need; sales start going down, and normally farmers leave, right. So, you have this very, very critical, very short period of time, where you have to make the market successful. So markets struggle a lot, and they depend a lot on free labor, which is volunteers, mostly.” (KI-p)

While multiple market leaders highlighted various aspects of the need and the value of having relationships with other market leaders, one key informant clearly articulated the need for connection as well as momentum:

“When you have something go wrong, there’s not always somebody you can talk to about it. And, so those relationships with the other market managers are really priceless, and that’s so, so important to the success long term of any market as the burnout factor is so high, because they don’t have support…. It was imperative that we did that [connected], to keep our momentum going. It’s the people that don’t participate that get burnt out, and they lose momentum.” (KI-f)

Key informants provided context for helping farmers markets make it through the initial phase of starting up a new market. They highlight the importance of building relationships as well as building momentum around the market.

Choosing What Gets Measured—Professionalizing Market Managers

In considering what gets measured, beyond financial performance, several key informants emphasized a need for training and professional development for farmers market managers. One of the provided reasons is that market managers shoulder a tremendous amount of responsibility, including managing the tensions of competing demands. As one participant noted, “I feel very responsible for the families of the folks we work with. They depend on us, and that's a lot sometimes to walk around with. So, I feel like we have to be on top of everything we're doing” (KI-r). Market managers burn-out and drop-out for multiple reasons, including salary. While another participant shared how much he enjoyed running the farmers market, he noted it was not a sustainable career option:

“Candidly, I’m leaving the farmers market. I’m actually the ex-manager at this point…. Moving forward, my career with them [another company] is more challenging and more rewarding financially as well. And so, I really don't have the time for it. Not to say the desire—I enjoyed doing it, but I just don't have the time to make it work. And my other job just is going to potentially pay me better in the future.” (KI-u)

One key informant provided perspective on professional development and training, describing three benefits: encouraging skill development, showing appreciation to employees, and retaining employees longer:

“I think that the training is good for the skill; but also, it is important for our staff to feel that they are taken care of. So, from a leadership perspective, I think it's also good that you get all the tools that you need and that you prefer, and you feel like the organization is investing in you; and that also helps them. And having a staff that are happy doing their job, and that is a big difference. Cause normally, we’ve seen that also, at many farmers markets. People get tired of managing in the markets, and when they're happier, they could stay longer.” (KI-p)

Several farmers market leaders noted the challenges of employee turnover. One key informant emphasized how professionalizing market managers goes beyond a simple request for pay equity; it impacts expanding the local food system and creating access to healthy foods:

“There are many, many, many talented people who could be, and should be, doing this kind of work. But they can't. They can’t do it because they can't get paid; they can't get paid enough to make a living.... You're running a small business or a small nonprofit, and you just have to have a professional staff person doing it…. If you've got a larger goal in mind, expanding the local food system, and creating access to healthy foods for local people, whatever it is. So long as you have that in mind, you need to hire somebody who can do that job.” (KI-g)

Overall, many key informants valued professional development and career paths for people interested in managing farmers markets.

Leadership through Place

Place can relate to many things, such as geographic location, time, or culture (Jackson et al., 2018). For the purposes of these findings about farmers market leadership, Place is a cultural construct. While these findings about farmers markets leadership use a primary perspective of Place, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. Place belongs to the community of people who live near the farmers market, and it belongs to the community of farmers and vendors who bring their goods to the farmers market. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Place: co-constructing leadership—community Lens and co-constructing leadership—vendor lens.

Co-constructing Leadership—Community Lens

In order to have a successful farmers market, multiple key informants indicated the importance of understanding the community and co-creating the farmers market. One key informant described the challenges in replicating a farmers market in another community: “Even though I was doing a lot of the same events and trying to set up the same sort of easy going vibe [at the market], it did not fly in [another town]” (KI-h). Customers need to have a reason for coming to the market, and these reasons vary from one community to another. As an example, one key informant, KI-l, did a study of their community and identified three types of customers: core, marque, and lifestyle. The core group attends every week. The marque group attends for special items, such as strawberries. The lifestyle group attends due to various personal reasons, such as a health issue or desire to educate children about healthy eating. Another key informant, described her core group as “the ones that are involved with local churches and local schools. They’re the ones who help me the most with advertising and getting the word out” (KI-g). In working to help a struggling market, one key informant described organizing community schools, businesses, and other agencies to help build support and momentum:

“You gotta really involve the community to make it successful, and there was no community there. Extension was involved, and the Chamber of Commerce was involved, and the schools, and some of the local nonprofits, and the kids from band.... Just a whole bunch of community organizations supported it…. I met with the economic development director, and the chamber, and I went and met with the brewery down the road, and the cidery, and someone from the school board; and we just got, we got all these different agencies involved.” (KI-f)

This process involves more than just meeting with a group; it involves understanding what the community needs and wants. KI-k described the process and what needs to be shared when co-constructing a market: “This is who we are. These are our values. This is our mission statement, and this is what we can do for you.” Moving beyond individual markets, one participant provides a broader perspective on farmers markets, generally:

“One of the things that's most appealing to me about farmers markets is, it is a cross section between economic stability, environmental stability, and social stability. It's what really drew me to farmers markets. Now, I’ve always been interested in environmental sciences, and they aggregate the fabric of a city and its citizens. So, I think it's the best place to combine all those worlds.” (KI-n)

Summarizing the perspectives of key informants, the community the market serves helps to co-construct the leadership of the market.

Co-constructing Leadership—Vendor Lens

In order to have a successful farmers market, key informants discussed the importance of the farmers and vendors that bring their goods to the market. At their core, farmers markets serve farmers. One participant notes, “What's the point in having a farmers market if it doesn't benefit the farmer?” (KI-m). One way in which farmers markets distinguish serving vendors is through rules, and those rules often center around geographic location. No rules, food-distance rules, and vendor-distance rules are examples of how place affects the leadership of the market. One market leader described the decision-making process for their market as “people run” and highlighted how vendors voted on all amendment changes:

“For big events, we’ll go ahead and plan the skeleton with the board and then bring in the members and have them vote on everything and get their opinions on what to add. But when it comes to big amendment changes, it's everybody. And we have to have a certain percentage to be able to go through with it.” (KI-o)

This farmers market had no limits related to distance, and the participant provided additional perspective: “I don't feel comfortable turning anybody down that has enough courage and drive to ask” (KI-o). Other farmers markets differed in how they developed their rules. For example, another key informant described a more informal process of having “vendors who are kind of designated as liaisons” (KI-d) to provide feedback and help to inform decisions related to the market. Another key informant represented a farmers market with a more formal set of rules and provided additional context for the rules:

“It’s community focused. It's not specifically vendor [focused], and it's not specifically consumer [focused]. It is bringing local vendors to local people, and keeping money within the local community, and creating a purpose and an area of growth that's mutually beneficial. That's why we have that 125-mile radius… We like to keep our food fairly local, so our people can hear, ‘Oh, [Vendor’s] produce is grown in [this county or that county].’ And so, people love to hear that, and we love stimulating the local economy.” (KI-k)

In describing a very active board, one key informant noted the importance, challenges, and benefits of having farmers and vendors co-construct the farmers market by serving on the board:

“It’s hard for them, for farmers in particular, or any vendor or any producer; it's just hard for them to consider what's in the best interest of the market, which may or may not be in their own personal best interest—so, their own business, [or] their own farm’s best interest. So, it makes it really, really hard; so that’s what we have to deal with. But by the same token, I wouldn't ever want to run a farmers market that didn't have representation of the producers, because they have great insight and wisdom into what and how, things that are working and not working. And that's the best way to get them to be honest and forthright is to put them on the board and give them a voice.” (KI-g)

Whether the processes were more formalized or less so, many key informants indicated the value of having vendors help to co-construct the leadership of farmers markets by sharing their wisdom and experience.

Leadership through Purpose

The Purpose lens of the Leadership Hexad focuses on Why leadership is created in farmers markets (Jackson et al., 2018). While the purpose of farmers markets begins with transactions around locally produced goods, the purpose can also include greater and more far-reaching aspirations (Betz & Farmer, 2016; Campbell, 2014; del Barco, 2019; Feenstra & Hardesty, 2016; FMFNY, 2019; Kumar et al., 2019; May, 2019; Witzling et al., 2019). While the findings in this study about farmers markets leadership use a primary perspective of Purpose, this lens does not function in isolation from the other five dimensions of the Leadership Hexad. These findings showcase examples of strong connections to leadership through Purpose: evolving the purpose and leveraging purpose to foreground other issues.

Evolving the Purpose

On its surface, the purpose of a farmers market may appear simple, but there are multiple ways in which it can evolve, such as community outreach and education. One key informant distilled the purpose of their market to its core: “The purpose has always been to allow the community an outlet to share with their goods, their produce, their baked goods, their crafts, their arts; and that focus has remained true” (KI-i). Another key informant stepped through an example of how the purpose for a market might evolve over time, once foundations are in place:

“So, markets struggle to do the basic stuff: to attract vendors, to attract customers, to work with their local authorities—that's a big nugget in and of itself. And then at some point, they become a little more community outreach oriented and start thinking about accepting SNAP and, ultimately, offering Virginia Fresh Match.” (KI-t)

While community outreach is one area a market can focus on growing the purpose, education is another area. Multiple key informants described entrepreneurial programs targeted toward youth, adults, and vendors. One key informant described the community’s enthusiasm and how they created a youth entrepreneur farmers market program: “They like having their own market day; so usually, they will do a Saturday” (KI-d). Another participant shared a more casual philosophy about their market’s educational goals: “We are here to have fun; we are here to sell good stuff; and, if possible, we’ll educate people while we're doing it” (KI-h). Several farmers market leaders are invited to educational activities beyond the market. For example, one participant described participating in career day at the local schools to help educate young people about farmers markets and entrepreneurship:

“I go to the schools, too, myself. Whenever they have career day, I’m on their list. I just go and talk about farmers market and all the different things you can find there, and how, if you have a business idea that is related somehow to food or agriculture, come talk to me.” (KI-q)

Another key informant described their organization as having “three different programs: We have the farmers markets, we have the food hub, and we have the education program.” (KI-p). Vendors also participate and lead educational activities as well. These activities ranged from the more informal, such as featured recipes, to more formal, such as cooking demonstrations. As an example, one key informant encouraged a vendor to lead a session on flower arrangements. “‘Have you ever thought about doing a workshop?’ And she was like, ‘I would love to do a workshop.’ [And I said,] ‘You let me know what you want per person. So, we’ll do pre-orders. You can get all the stuff and all the money goes to you’” (KI-o). Many key informants noted how the Why of having farmers market leadership at their market often aligned with the personal values and goals of those involved in leading the market.

Leveraging Purpose to Foreground Other Issues

In addition to having the purpose of a farmers market evolve over time under the right conditions, key informants described opportunities associated with leveraging the farmers markets toward additional goals. Key informant talked about using the farmers market as a point of entry for bringing about community change: “If you change a food system, you change a community” (KI-e). Another key informant described the experience of working with another organization that was oriented toward food access:

“For us, the markets were not the goal, right; having a farmers market was not the goal that we had. The market, for us, has always been a means for something else. So, [it was] a means to create food access, [and] a means to improve the lives of farmers. We tried to see the market as a tool, and so we could create relationships with other organizations that would benefit from local food.… The farmers are going to come, and you can use—and we’ve been doing that—using that trade to bring more fuel to feed other goals that the organization has. But the market is the key part, but it's the tool for these other things.” (KI-p)

Another key informant expanded upon how farmers markets fit into the larger picture of food access and food security: “The way it works, when it works, is that all the different community’s sectors come together, who are interested in food security and food access. So, farmers markets become part of that food system orientation” (KI-t). Farmers markets seem a natural fit as part of a community effort around food security and access. Other means of leveraging purpose also exist. One key informant shared a passionate desire for professionalizing farmers markets’ management as a means to improving and expanding the local food system:

“If I accomplished one more thing, in my life that would be it: to get the market managers the respect that they need and the pay equity that they deserve—not because they're lovely people who work hard, but because they are a means to an end. They are the people who will make this local food system expand and be what it can be. And without them, it is not going to happen; it just isn't going to happen.” (KI-g)

These examples provide context on leveraging the purpose of farmers markets toward other missions and goals.

Objective 4: Build capacity for future research and practice

The southern SARE grant helped to build capacity for future research and practice through learning the process for writing a grant, developing and conducting IRB-approved research, and identifying opportunities for future research. First, the Southern SARE Graduate Student Grant provides graduate students an opportunity to learn about the grant-writing and management process. While the concept of getting a grant is simple, it is helpful for new researchers to gain insight on how the university processes and handles grants. Secondly, developing an IRB-approved research protocol is an incredibly valuable and useful experience. The Internal Review Board (IRB) was developed to protect the rights and welfare of research subjects. Learning how to prepare a research protocol that explicitly protects the rights and welfare of the participants in the study will help with conducting future research. Lastly, this research has helped to illuminate additional avenues to explore related to farmers market leadership and sustainable community food systems.

References:

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

Farmer’s Market Online. (2018, May 02). Farmer’s Market Online Open Air: Virginia Farmers Markets Directory. http://www.farmersmarketonline.com/fm/Virginia.htm

Jackson, B., Nicoll, M., & Roy, M. (2018). The distinctive challenges and opportunities for creating leadership within social enterprises. Social Enterprise Journal, 14(1), 71.

Local Harvest. (2020, September 18). Local Harvest. https://www.localharvest.org/

U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA AMS). (2019). National count of farmers market directory listings. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/NationalCountofFarmersMarketDirectoryListings082019.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA AMS). (2019, September 25). National Farmers Market Directory. https://www.ams.usda.gov/localfooddirectories/farmersmarkets

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS). (2020, September 24) Virginia Grown: Virginia farmers' market resources. http://www.vdacs.virginia.gov/vagrown/frmsmktresources.shtml

Virginia Farmers Market Association (VaFMA). (2020, February 8). Find a Market. Virginia Farmers Market Association. https://vafma.org/virginia-markets/

Virginia Tourism Corporation. (2018, April 25). Virginia's Farmers Markets. Virginia is for Lovers. https://www.virginia.org/farmersmarkets

Wilson, M., Witzling, L., Shaw, B., & Morales, A. (2018). Contextualizing farmers’ market needs: Assessing the impact of community type on market management. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 49(856-2019-3184), 1-18.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Information about this SARE funded research has been shared at a departmental conference and an online presentation of a master's thesis. In April 2020, preliminary research was presented at the Agricultural Leadership and Community Education Forum 2020 Virtual Conference. The presentation was titled, Farmers Markets Factors Influencing Success and Failure: Essential or Not? Approximately 20 students, faculty, and staff attended the conference. In August, 2021, the research was presented at part of a master's defense. The presentation was titled A Qualitative Exploration of the Influence of Leadership on the Success and Failure of Farmers Markets in Virginia. Approximately 10 people attended the public presentation.

This research will continue to be shared at departmental seminars, graduate research seminars, and local conferences. Research findings will be presented at regional and national conferences, and manuscripts about the influences of leadership on farmers markets will be published in appropriate journals, such as Agriculture, Social Enterprise Journal, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, and American Journal of Alternative Agriculture.

Project Outcomes

As one participant in this study noted, “What's the point in having a farmers market if it doesn't benefit the farmer?” (KI-m). Farmers markets serve farmers and their community. Farmers markets provide a venue for establishing relationships within the community and along the short food supply chain. This study will help contribute to future sustainability by identifying current trends with farmers markets, which are part of the local and community food system. The study will help guide individuals or groups involved in leading social enterprise initiatives, such as farmers markets, cooperatives, and organizations involved in the short food supply chain. It may also be relevant to people involved in Cooperative Extension and land grant universities. People involved in local government and municipalities may find it of valuable to learn the perceptions of farmers markets leadership on the importance of local government support.

As a graduate researcher exploring farmers markets in the community food system, three aspects of this research have influenced my understanding of farmers markets and leadership. The first insight is how farmers markets are both fragile and resilient. For example, farmers markets appear and disappear with regularity, and one key informant noted this this phenomena. “Yeah, there's so many [farmers markets] out there that are very fragile, and kind of just spring up, and die out, before a lot of people even know that they’re there” (KI-n). While they are fragile in some instances, they can be resilient in other places, which is described by another key informant. “There’s always kind of just been this, ‘it pops up for a few years, and then it dies down, and then it pops up and it dies down'" (KI-d). Gaining this knowledge about the fragility of farmers markets leads me to wonder whether leadership and those with a passionate commitment to food access can find farmers markets to be a reliable resource across the state. The second insight is to ask if there is potentially a shortage of farmers and vendors to provide local goods and value-added products to support the community food systems in Virginia. While multiple participants in this study indicated that they had waiting lists for their markets, they acknowledged that these markets were well-established. Fledgling markets have difficulty attracting and retaining vendors. I question whether there are too many farmers markets or too few. If the number of farmers were greater, I think more farmers markets would survive the first phases of startup. Thirdly, leadership theories, frameworks, and principles come in many shapes and forms. I think Jackson et al.'s (2018) social enterprise leadership framework influenced what I learned during the study. If I had chosen another leadership approach to help inform the research protocol, such as transformational leadership or path-goal theory of leadership, my findings would have been different.

Additional research opportunities include further attention to how the pandemic affected leadership, leadership capacity, networks, access channels, and social capital around the SFSC, including SNAP and the Virginia Farmers Market Association. Also, there may be value in gaining a better understanding of the relationship between farmers market leadership and food access—barriers and challenges, beyond the influences of the pandemic. As noted by key informants, farmers and municipalities contribute to the success and challenges that farmers markets face. How do these entities make their decisions to support, or not, a farmers market? What can be learned from their leadership approach? Lastly, this study recommends further exploration of the professional development needs of Virginia farmers market leaders. One opportunity would be to conduct a study similar to Wilson et. al. (2018), applying micro-strategies to assess professional development needs across the state in order to tailor opportunities in more meaningful ways.