Final report for GS20-223

Project Information

Intercropping has been a successful tool for farmers for thousands of years. Modern agricultural practices have diverted attention away from intercropping, but this has come at the price of sustainability. Reliance on monocultures supported by pesticides has led to reductions in pesticide efficacy, contributed to environmental pollution, and harmed human health. Intercropping can increase economic return for farmers through yield increases, and as a component of integrated pest management (IPM). However, successful implementation of intercropping can be highly context-dependent, depending on the specific crop, timing, and spacing arrangements (scale of inter-mixing of crops) suited to a particular region. This project seeks to evaluate intercropping as a tool for sustainable vegetable production on small organic farms in the Southeast. This project will address the question of how the efficacy of intercropping varies with the spatial scale of mixtures, and evaluate the use of a novel combination of kale (Brassica oleracea) and elephant garlic (Allium ampeloprasum). Previous work suggests that Allium species (onions, garlic, leeks) can be beneficial companion plants for many crops. Elephant garlic is well suited for intercropping with kale in the North Florida region, but its use has not yet been evaluated. Working with a small farm and an agricultural research station we will use organic practices to grow kale monocultures and dicultures with elephant garlic at different spatial scales of mixture. Insect pests, damage to plants and natural enemies will be surveyed; kale and garlic yield will be recorded, and net costs and benefits to farmers determined.

The objectives of this project are to evaluate intercropping as an economically viable and environmentally sustainable alternative to pesticide use and monocropping for pest suppression. The project will also examine differences in the benefits (pest suppression, yield) to farmers in using different scales of intermixing of kale and elephant garlic. We expect pest suppression to result from volatiles that repel herbivores or disrupt herbivore-searching behavior, as well as potentially increasing the diversity of natural enemies. We are testing different spatial scales of intermixing because, due to the short-range action of plant volatiles, it is possible that intercropping with elephant garlic will only be beneficial when the plants grow in close proximity.

This project is intended to engage local farmers practicing sustainable agriculture in the Tallahassee area. This project was developed in consultation with two local farms (Turkey Hill Farm, Full Earth Farm) that are both leaders in local sustainable agriculture and in the Red Hills Small Farm Alliance, a coalition of 60 farmers in north Florida and south Georgia that share an on-line farmers market delivering to the Tallahassee area. Both of these farms grow kale and elephant garlic, but they do not currently practice intercropping. In addition to working at a regional agricultural research station, we propose to leverage the planned expansion of a local small farm (Longview Farms) from beef and poultry production into growing vegetables for market, using some of their new vegetable beds for experiments at a second site.

Our primary goals are to:

1) Evaluate whether plots of kale (Brassica oleracea, cultivar: Lacinto) intercropped with elephant garlic (Allium ampeloprasum) enhance biological control, insect diversity, and increase yield compared to kale monocultures. We will test three different spatial scales of intercropping.

2) Disseminate research to farmers and growers, and conduct science outreach to elementary school students.

Research

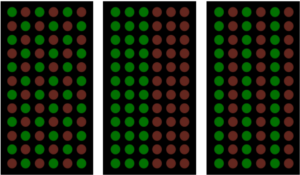

The experiment will consist of three treatments of kale-elephant garlic dicultures; elephant garlic intercropped within a row of kale, elephant garlic intercropped in alternating rows, and elephant intercropped with kale in side-by-side blocks (Figure 1). Because small farms harvest kale by hand and as individual leaves to be sold in bundles, alternating kale and elephant garlic plants within rows will not interfere with the kale harvest.

The research will be conducted at Longview Farms, a local farm in Havana, Florida, and at the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Science (UF/IFAS) Extension research field, located in Quincy, Florida. Kale and elephant garlic will be grown at both sites. Longview Farms will have 12, 10 x 19.5 foot (3.33 x 6.5 m) plots, each surrounded with a 6-foot (2 m) border of bare soil. The boundary of bare soil is intended to reduce random insect movement between plots. The 12 plots will contain three replicates each of the three intercropping treatments plus the kale monocultures. The UF/IFAS Extension research field will consist of 24, 10 x 19.5 foot (3.33 x 6.5 m) plots, surrounded with a 6-foot (2 m) border of bare soil, allowing for twice as much replication. Each plot will have six rows of crops. At each location, elephant garlic and kale will be grown from October to May. Planting in the fall will be dependent on when the weather begins to cool down. Kale plants will be started in the greenhouse and transplanted in the field once conditions are suitable. Compost or manure will be used to fertilize all plots within treatments.

Objective 1 — Evaluate whether plots of kale intercropped with elephant garlic enhance biological control, insect diversity, and increase yield compared to kale monocultures.

Treatment 1: kale intercropped with elephant garlic within rows

Treatment 2: kale intercropped with elephant garlic side-by-side in blocks

Treatment 3: kale intercropped with elephant garlic in alternating rows

Treatment 4: kale monoculture

The abundance of herbivores and natural enemies will be sampled biweekly on kale and elephant garlic crops. Observations and sampling will begin once elephant garlic has emerged from the soil and kale plants are established, approximately four weeks following planting. Multiple sampling methods will be used to assess the abundance and diversity of insects within different trophic guilds and to examine the composition of arthropod communities between plot treatments. A subset of individual plants within each plot will be sampled for visual observations of insect herbivores and predators. Yellow sticky traps will be used to sample aphids, leafminer adults, and whiteflies. Pitfall traps will be used to sample soil surface insects. A Berlese funnel will be used to assess arthropod diversity within soils. All insects will be identified to families, and when possible to species or genus.

Damage to a subset of kale leaves within each treatment will be recorded along with the insect observations, on a scale of 1-4 as follows, 1= 0-5% damage, 2= 5-20% damage, 3= 20-50% damage, and 4= >50% damage. Location of damage on the plant and characteristic types of damage (chewing, leaf curling, sucking, etc.) will also be recorded. Kale harvests generally occur multiple times over the season, with farmers removing individual leaves as needed. We will calculate yield as the total number of leaves and weight harvested at each time interval, as well as cumulatively over the season. Elephant garlic will be harvested in late May or in June, 2021, depending on weather, and yield will be recorded.

Statistical analysis

Kale and elephant garlic yield and damage, and insect abundance and diversity will be compared among treatments. Data will be analyzed separately for the two locations, as the UF/IFAS site and the farm site differ in several respects. Insect abundance within trophic guilds between the treatment plots will be estimated using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) with a Negative Binomial likelihood, if the data meet model assumptions. If necessary, appropriate transformations of the data will be done to meet model assumptions. A Negative Binomial likelihood will be used to account for overdispersion, since insect abundances are generally clumped. Replicate plots will be modeled as a random effect to account for repeated sampling. The effect of treatment on kale yield and damage within plots will be compared using ANOVA. Soil arthropod diversity will also be compared between plot treatments using ANOVA. Once samples are sorted into taxonomic groups, the proportion of herbivores to predators will be evaluated in each plot using ANOVA. Data will be transcribed from fieldbooks and backed up regularly to a cloud-based server and made public upon publication, or within a year of student graduation, whichever comes first.

Objective 2 - Disseminate research to farmers and growers, and conduct science outreach to elementary school students.

Presentations will be made at farmer outreach events such as the annual UF/IFAS Field Day in Quincy, FL to inform vegetable growers about the potential benefits of intercropping in general, as well as results from growing kale intercropped with elephant garlic. Many local farms around Tallahassee grow both kale and elephant garlic. After the first year of data collection, preliminary results will be presented at the Southern Sustainable Agriculture Working Group (SAWG) Conference, Georgia Organics Conference and Expo, and the Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting. A manuscript will be prepared during this time to submit to a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Longview Farms has an established partnership with Cornerstone Learning Community, an independent preschool – 8thgrade school in Tallahassee, for activities related to their science curriculum. This project will include activities related to entomology, insect food webs, and when possible will engage students in the scientific method during their field trips to visit the farm.

In 2022, I have presented preliminary results from the intercropping experiment conducted in 2021 at the Ecological Society of America 2022 annual meeting. Preliminary results suggest there was no significant effect of intercropping elephant garlic with kale on arthropod abundances compared to kale monocultures. However, there were significant differences in arthropod abundances between the small farm field site and agricultural research station, suggesting the surrounding habitat matrix may contribute to mediating effects of intercropping. I am still entering additional data and processing samples but anticipate presenting and distributing pamphlets with results to local farmers once all the data have been analyzed. I will also conduct a follow-up lab experiment this year to aid in the interpretation of results from the large field experiment.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

The pandemic in 2020/2021 made conducting outreach activities for this project challenging. I had the opportunity to record a brief presentation on a local farm (Longview Farm) for 3-5th grade students discussing this project and its relatedness to sustainable agriculture. As COVID restrictions were lifted I co-developed and participated in several outreach lessons from 2022/2023 with 4-5th grade students aimed at teaching insect food web concepts in vegetable gardens on their campus.

Project Outcomes

Although intercropping elephant garlic with kale did not necessarily reduce pest loads compared to monocultures in my study (data analysis is still in progress), my study could still be a catalyst for conversation among farmers about cropping patterns or crops that can grow synergistically and provide different ecosystem services that are tailored to their region and goals, especially given that garlic has been shown to be protective in other locations and crops. Planting crops that can benefit each other or provide some ecosystem service could be critical for future sustainability as we continue to rely on large scale agriculture that depletes soil and human health to produce large yields. Growing more than one crop can diversify streams of income for a farmer and improve the ability to recover from a lower yield for a single crop from one year to the next. For small farmers, the scale at which intercropping can be implemented will be drastically different than large scale farms, thus examining scales of mixing that are practical and provide benefits to the farmer, as addressed in this project, is an important step since the success of intercropping is highly context-dependent.

Over the course of the project, I grew an even greater appreciation for the preparation, time, and labor necessary to grow crops for market on small farms. Participation in this project allowed me to see firsthand the challenges (efficiently planting/harvesting crops, marketing, getting crops sold quickly before spoiling in order to sustain production, challenges in getting naturally grown certifications) small farmers face in growing produce for market. Working with these farmers made me realize the vast labor that goes into making sustainable produce, considering the processes involved can be generally slower and more laborious than agriculture done at a larger scale. For example, for this project we did not want to use an herbicide to keep weeds out of the experimental plots as is typically done in industrial agriculture, but hand weeding took considerably longer to do. However, with enough hands the labor can be light. As some of our small local farms already do, involving more community members in the growing process and making them more aware of where their food comes from can potentially make this endeavor easier to sustain in the long run.

As a scientist, this project provided me the opportunity to contact and collaborate with several local farms and a USDA scientist in the generation of the research proposal. Throughout the growing season I participated in discussions on ways to grow these crops successfully and pests I would be likely to encounter. Working with these farms also allowed me to communicate my research ideas to a more general audience and generate discussions around the effectiveness of intercropping and sustainable agriculture in general. These sustained contacts between the lab and our local farmers have been extremely valuable throughout the project and will be fruitful for future research and collaborations.

Participating in all the steps to produce crops in a sustainable way for this project made me realize how many ways the process can become unsustainable at some point (using different kinds of seed mixes from conventionally sprayed fields, using chemicals to reduce pests or increase growth, air pollution from harvesting machines or using exploitative labor). Careful and mindful planning is necessary, and sustainable agriculture involves not only growing crops in a sustainable way but also using labor fairly and sustainably.

It seems beneficial to conduct more research on companion plants that work well together across many different regions and determine at what scales/cropping patterns they are likely to be beneficial. Previous research has shown that intercropping can be successful, but effects are highly variable. Therefore, future research should focus on implementation of intercropping and companion planting that is tailored to their specific region and perhaps will provide more general information on contexts when intercropping is useful or not.

Increased funding for small farms that can cover labor and other immediate needs necessary for their success seems fruitful in the pursuit of sustainable agriculture and a scaling back of large-scale agriculture that has produced many negative effects to environmental and human health. This would allow for agriculture to be done by more smaller farms with more sustainable practices and could elicit more community participation across many regions.

Although I benefitted a lot from the process of working through implementing this project (contacting farmers, planning the growing season, conducting the research, disseminating research results, etc.), I came to realize that my identity as a Latina woman might have influenced how receptive or engaged professional staff were with me throughout the growing season. Although the small farmers I worked with were encouraging and enthusiastic about answering my questions, my experience with professional research station staff made me question whether staying conducting research in sustainable agriculture would be a great fit for me long term. I perceived no malice from staff but did feel that I was not taken seriously or encouraged in the more male-dominated environment of the research station. Perhaps connecting underrepresented minorities who have received SARE grants with each other could alleviate feelings of isolation/lack of sense of belonging in the field and offer a place to discuss other obstacles recipients could encounter throughout the process. Additionally, perhaps a training for recipients of the SARE grants and their mentors could provide some more information on navigating cultural divides between academic researchers and agricultural professionals. This could also possibly help bridge communication gaps between sustainable agriculture movements and industry agricultural industry professionals.