Final report for GS20-230

Project Information

Successful insecticide (IRM) and herbicide (HRM) resistance management (RM) in agriculture is contingent on the aggregation of insect and weed best management practices (BMPs) on the farm-scale to the landscape level. Endeavors such as this require significant coordination and collaboration across diverse sectoral boundaries in agricultural production, which invoke social, economic, and political forces to structure the incentives, norms, and rules regarding RM. Currently, these structures are largely designed to serve diverse farm-scale management practices, not landscape level. Therefore, research is needed to investigate alternative solutions that re-organize these structures towards the success of implementing landscape level BMPs.

One pathway to alternative solutions is through cooperative management strategies, where multi-stakeholder collaborations within an agricultural production system work together to devise best management practices, and share costs, benefits, and knowledge across diverse institutional boundaries. Critical to the organization of these systems are social conditions like trust, reciprocity, and social capital that mediate the social ties that promote exchanges of information, knowledge, and resources related to IRM and HRM. To study these conditions, I endeavor to pursue an exploratory, mixed-methods network study of Eastern North Carolina “Blacklands” agriculture. Using both qualitative interviews and social network analysis methods, I can uncover how social conditions structure and influence information and knowledge exchanges, and how they may be leveraged to enhance coordination and collaboration, and potentially lay some groundwork for the development of future cooperative management programs.

Objective 1: Investigate the diversity of farmer’s best management practices for insect pests and weeds, and how concretely these connect to shared practices in IRM and HRM.

RQ1: What role does personal knowledge, values, and identity play in how farmers make sense of resistance management?? To what degree are these knowledges and perspectives shared with other farmers?

- What are their “best management practices”?

- What are their biggest challenges?

- What are they concerned about?

One of the key questions for assessing a management system at the landscape level is understanding how farmers are implementing BMPs for insect and weed management at the farm scale. What are some common features of these management practices? How do they relate to individual farmer knowledges, perspectives, and values? Are any of these elements shared? Approaches to farm-scale management will be contingent on individual farmer perspectives and knowledges in addition to resource availability, which may result in very diverse practice. The challenge of aggregation to landscape level coordination is synthesizing this diversity of practice into a landscape level approach. Additionally, a farmer's unique knowledge and perspectives on IRM and HRM and the degree to which it is incorporated into their own insect pest and weed management practices has implications for promoting cohesive cooperative management. How a farmer recognizes and understands their role in resistance management may differ from other farmers, and may or may not be anchored in similar values, perspective, or knowledge. Interviewing farmers about their conceptual perspectives, local knowledge, and values to understand the diversity of practices currently on the ground is therefore foundational.

Objective 2: Map out network connections between who farmers communicate with, share knowledge and collaborate with on different aspects of resistance management.

RQ 3: What role do personal networks play in how they understand, make decisions, and structure their practices related to resistance management?

- Who do farmers talk to about IRM and HRM? Who are the most trusted sources?

- What influence do different sources have on resistance management related decision making?

Each farmer will communicate their own unique management plans tailored to their specific farm characteristics and resource capacities, in addition to their personal knowledges that they use to facilitate said plans. However, farmers also heavily rely on information and knowledge from other actors when designing their management plans and making decisions concerning IRM and HRM. Who are these most trusted sources, and why do farmers trust them? Additionally, because there is a collective interest for all farmers to engage in effective insect pest and weed management practices, are their informal collaborations between entities that already exist? Who is involved and how are they organized? Mapping out social ties based on information and knowledge transfer, and management collaboration can illuminate important social factors that could be leveraged to enhance the potential for coordination in implementing landscape-level BMPs.

Research

General Approach

I will use a mixed methodological approach called qualitative network analysis (QNA) method to accomplish objectives 1 and 2 simultaneously. This approach incorporates both qualitative and quantitative methods which takes place through a protocol designed to collect "egocentric" network data alongside semi-structured interview data1. Quantitative, egocentric data gathers information on social network connections between farmers and other actors, while the qualitative interview data gathers information on famer's personal meaning-making processes. The advantage of utilizing this approach is too capture both a respondent’s set of social ties and concretely understand how those social ties influence, and are influenced by, the perspectives, values, and practices of the individual. In network analysis terms, this means that QNA can work to understand the multi-level linkages that exist between network structural patterns, network actors personal networks, and the personal meanings actors attach to their network connections instead of just one of these levels 6,11.

Sampling Strategy

Farmers are the chief decision makers and facilitators of IRM and HRM practices, making them the key stakeholders involved in any cooperative management system. A farmer-centered, and farmer-empowered collaborative approach can result in the widespread realization of BMPs tailored to a local context’s social conditions in addition to the biophysical3. Therefore, inquiries into how social networks can be leveraged to develop landscape level coordination of resistance management should take farmer-centered approach to the investigation of perspectives, practices, and social connections. Therefore, my primary study sample will consist of local Eastern North Carolina farmers. It is important to note that this is not a comprehensive, whole-network study, but rather an exploratory “landscape analysis”. Time and resource constraints inhibit me from performing a comprehensive network study, but an exploratory study can provide meaningful insights if sampling is done thoughtfully.

For study sample 1, Farmers were recruited based on their involvement in field crop production, with emphasis 3 major commodity crops commonly grown in these communities: corn, cotton, and soybean. I limited my sampling to specific counties in central and eastern North Carolina because of their geographic proximity to one another, but also because I have previously established contacts in the area that might make sampling more efficient. In addition, I included a second study sample of extension agents and researchers that focus on HRM and IRM practices, and some additional actors involved in public and private sector to collect data from. The inclusion of this sample is to provide a broader view of the larger knowledge networks that exist around farmers, crop production, and resistance management practices in eastern North Carolina, which I will draw from to contextualize farmer's own personal networks, and the influence that other actors have in these networks.

A second study sample that I included in this study were extension agents, industry representatives, and government employees. The communication ecosystem surrounding resistance management is embedded with diverse forms of expertise that generate and exchange information and knowledge with farmers across these different sectors. Understanding the personal communication networks of these additional groups -- and how they compare to each other, and the farmer networks -- adds to our understanding of how social capital is organized and distributed in the wider network of stakeholders. I recruited extension agents, industry representatives, and government employees in-person at extension-faciliated grower meetings, field days, and expos held in various counties across eastern North Carolina.

Specific Methods and Research Questions (Details about Recruitment and Data collection logistics in “Timetable” section)

Objective 1: I will employ semi-structured interview methodology to elucidate details about farmer’s individual resistance management practices. Questions in these interviews will ask about various aspects of farmer perspectives, knowledges, and values related to insect pest and weed resistance, which will later be used to understand how farmers construct their management plans from their own meaning-making practices. Interview methodology has a long history in social science, specifically the fields of anthropology and sociology, and has been used to complement network studies in past research11. It is not a method that is traditionally applied to the topic of resistance management, which is a novel element to this approach.

Objective 2: The way that this QNA method works is through a survey tool and interview methodology known as concentric circle methodology (CCM). It is utilized as an interactive tool that allows the survey respondent to actively construct a mental model of their own social network in front of the researcher1. The researcher first administers a network survey to gather data on a subject's network relationships and communication patterns, and then follows up with an interview to ask more open-ended questions about those patterns of communication and relationships. The researcher can constructs an ego network map to model an actor's subjective network map, and can use this to understand if any influential actors that exist across their ego networks 9. Influence of certain actors in these embedded networks should become apparent if multiple individual farmers describe social ties to the same knowledge source, and significant patterns that are apparent across different mental models can suggest insights into how farmers think about resistance management. Interview questions pertaining to the nature of relationships between actors and their network connections can be asked based on the subjective network map. In this way, the subjective network maps function as an interview tool as well as a data collection output, and can address information and knowledge exchanges simultaneously by mapping different elements of social ties1.

Analysis

Objective 1: Qualitative interview data will be analyzed using abductive analysis coding techniques12. This is different than traditional grounded theory techniques that seek to establish sentence-by-sentence meaning making patterns within interviews, and instead seeks out broader thematic meanings from more aggregated data. This is an important methodological choice, because preforming grounded theory takes an exponentially longer time table to accomplish, and treats each interview subject as their own unique extended case which involves a substantial amount of qualitative data. Specifically, my coding scheme will pull out the important perspectives, knowledges, and values communicated by farmers, and analyze these data to detect elements of shared experience and values, which is important for future possibilities of coordinating shared practice.

Objective 2: Using standard social network analysis software, UCINET, I will construct the personal knowledge networks from the collected ego network data for each farmer in the study. I will map each social tie to each actor that interacts with farmers in a resistance management context to first understand who farmers communicate and exchange knowledge with in a resistance management context, and then aggregate all the ego-networks of every respondent and there social ties in order to uncover shared social connections, and broader patterns of trust and influence across the personal networks 9. Relating this back to the perspectives of farmers expressed in interviews, I will look for the social ties that are most highly correlated to trust, influence, and practice. It is important to assess the ego-networks in conversation with the interview data, because there could be actors that are a) are very well connected to farmers, but exert little influence on their practices via knowledge exchange and b) actors who are not well connected to farmers, but exert a lot of influence on practice via knowledge exchanges at key points in the network. A comparison like this should provide insights on how missing important details about influence and farmer practices, and how these network connections can be leveraged for greater collaboration on the basis of different factors relating to influence and trust.

Final Project Report Update

Data Collection

Our data collection consisted of two steps: an electronic questionnaire and a live interview. Participants were first asked to fill out the questionnaire and submit results to the research team. Upon completion of the questionnaire, participants were then invited to participate in a live interview either over the phone or through video chat, in accordance with the participant’s preference during an active phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of these interviews were conducted live via the phone, and a few over video chat.

Our protocol was designed to gather two forms of data; 1) social ties illustrating personal network connections to other stakeholders and 2) perspectives on social interactions with other stakeholders. Network data were elicited in the electronic questionnaire, which asked participants to list the names of individuals that they communicated with on issues related to pest management and resistance management. This name-generating (Crossley et al, 2017 ; Borgatti et al, 2013) portion of the survey was critical to identifying the social ties of each participant around information and knowledge exchange. Participants were able to list up to 15 names and occupations of unique individuals, with no restrictions on the exact type of communication they used with that individual. This activity produced 122 unique individuals (alters), and 161 total network ties across the 25 different personal networks of our participants. For each individual named, participants were then asked some basic name-interpreting (Crossley et al, 2017 ; Borgatti et al, 2013) questions about the nature of that relationship, such as how long they had known each other, the preferred method of communication, and the kinds of subjects usually discussed. We also asked basic questions on stakeholder learning, trust, and value alignment with other stakeholders in their personal networks. Those questions were constructed using likert scales (1-5), and asked about level of knowledge, trust, personal and professional value alignment, and knowledge adoption.

|

Learning, Trust, and Value alignment Likert Scale Questions |

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree |

Table 1: Linkert scale questions on learning, trust, and value alignment in the social ties of stakeholder personal networks

Live, semi-structured interviews followed the completion of the electronic survey. Every participant was given the opportunity to participate in this interview portion, but some participants opted out. In total, n = 22 interviews were conducted. The first part was specifically designed to follow up on the name interpreting questions of the electronic interview, asking participants to recollect communication events with specific alters they had named in the survey, and responding to the following questions:

- What kinds of specific topics did you usually talk about?

- What kinds of things do you learn from this person?

- What do you think this person learns from you?

- From your perspective, what makes this person a good source of information and knowledge?

The goal of this first part of the interview was to gather more information on the kinds of topics discussed between participants and other stakeholders in the network and what participants took away from these interactions. Part two of the interview focused more on the participant’s perspectives and experiences related to pest and resistance management. The interviewer asked the following questions:

- What are your biggest concerns related to insecticide resistance and herbicide resistance?

- Are you concerned more about insecticide resistance or herbicide resistance? Why?

Live interviews were conducted between September 2021 and March 2022. Interviews lasted anywhere from 45-90 minutes. This activity produced roughly 25 hours of recorded audio/video for analysis. All audio was partially transcribed either by hand or by transcription software provided by the North Carolina State ZOOM platform. All audio and video files were stored securely in encrypted data files on North Carolina State's secure cloud servers in accordance with IRB approval from North Carolina State University Institutional Review Board under protocol #23956.

Data Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in two steps; an ego-network analysis of personal network ties and a qualitative analysis of interview data (Bourne et al, 2017). For the ego network analysis, personal networks were built for each stakeholder based on the social ties identified in the network survey. The degrees of each ego (number of different individuals named in a personal network) and alters (showing the number of egos who named a particular alter) and the total size of the network (e.g. total number of ties; total number of nodes) were calculated using social network analysis software UCINET (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). Tie dispersion (number of ties that a node has with other node subgroups) was tallied to gain an understanding of which actor subgroups were most often connected to another (Borgatti et al, 2013). Lastly, we constructed summary statistics for questions focused on communication, such as how often egos and alters interacted with each other, what kinds of topics they usually talked about, and in what locations. We also summarized data from questions about ego-alter relationships, such as how long an ego and alter had known each other, what their relationship status (e.g. friend, business contact, neighbor) was, and the influence of those relationships on each ego.

Next, we performed an analysis of social learning and social capital based on two data outputs: 1) the structure of bonding and bridging ties across personal networks (Borgatti et al, 2013) and 2) the participants' experiences and perspectives on learning interactions, trust, and reciprocity in the qualitative interview data (Bourne et al, 2017). We first tallied up the total bridging ties and bonding ties for each participant and compared how different personal network structures indicated different potentials for social learning based on these ties. For the purpose of this analysis, we used a basic definition of bonding and bridging ties, where bonding ties refer to connections between a stakeholder and members of their same subgroup (e.g. grower, extension agent, industry representative) and bridging ties as connections to members of different subgroups.

Next, we used a thematic coding scheme to draw out perspectives related to social learning and social capital within the personal networks. Specifically, we selected and analyzed quotes that illustrated egos' experiences in learning interactions and their perceptions on trust and reciprocity in their personal networks. For social learning, we coded participant interview responses to draw out the different types of learning interactions experienced by our participants and their perspectives on how these experiences affected their use of resistance management knowledge. We highlighted different sections of the interview transcripts with the codes like “LEARNING” and “IMPACT” to indicate moments when they took up new information and knowledge, and the kind of impacts that learning had on a participant’s practices. Themes for social learning spoke to how different stakeholders prefer to engage with new knowledge and apply it to their own practices. For social capital, we coded our interview data for participant perspectives on trust, reciprocity, and value alignment in their personal network relationships. We used simple codes like “TRUST” and “VALUES” and “GOALS” to indicate when participants talked about their belief in other stakeholders and their perceptions on how their values and goals aligned with others in their personal networks. Themes on social capital also revealed insights on how trust is built in different stakeholder relationships, but also areas of potential value conflicts. All coding and analysis was conducted using the Dedoose platform (Salmona & Lieber, 2020).

Final Project Report Update

Network Survey Results Summary

In total, 162 social ties (e.g. undirected network edges) exist across all (n=25) participants’ personal networks of information and knowledge exchange around resistance management, with an average degree of 6.48 ties per ego. Five main categories of stakeholders comprised personal network ties around information and knowledge exchange for pest and resistance management: growers, extension agents, researchers, industry reps (e.g. seed dealer; chemical suppliers) and crop consultants. The largest personal network reported had 14 ties , while the smallest ones had 2 indicating a variable range in how many individuals stakeholders communicate with about resistance management issues.

|

EGOs |

Total Ties |

Agents (Alter) |

Researchers (Alter) |

Growers (Alter) |

Industry Reps (Alter) |

Crop Consultants (Alter) |

|

Agent EGOs (n = 10) |

77 |

9% |

27% |

57% |

7% |

0% |

|

Grower EGOs (n = 10) |

44 |

25% |

25% |

11% |

23% |

16% |

|

Industry EGOs (n = 3) |

24 |

0% |

0% |

63% |

29% |

8% |

|

Government (n = 2) |

16 |

12% |

50% |

13% |

0% |

25% |

Tie Dispersion across subgroups – Ratios of social ties between different alter subgroups and each ego category

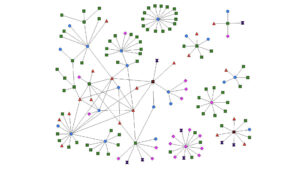

Aggregate ego network sociogram – Illustrates social ties collected as a result of the network survey, representing the exchange of information and knowledge about resistance management related topics between different stakeholders. Nodes are color-coded to identify different ego categories. Blue circle nodes = Extension Agents; Green square nodes = Growers; Pink diamond nodes = Industry Reps; Red triangle nodes = Extension Researchers; Purple hourglass nodes = Crop consultants; Brown circle-in-box nodes = Government employee

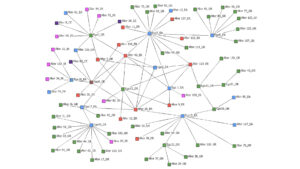

Main Ego Neighborhood – Illustrates the connections between egos that share the most social ties between one another. Nodes are color-coded as in figure 1, and also attached with an ego (“Ego”) or alter (“Alter) designation and subgroup code for each node. EA = agent, ER = researcher, GR = grower, IR = industry representative, and CC = crop consultant.

Sample personal networks of different stakeholders - Above are examples of the different configurations of personal networks constructed from name-generating questions on the network questionnaire. Different subgroup classifications are color coded. Blue = extension agent, Green = Grower, Pink = industry representative, Brown = government employee, Purple = crop consultant, Red = university researcher. Row 1, figures 1a-1d represent different extension agent personal networks. Row 2, figures 1e-1h represent grower personal networks. Row, figures 1i-1l represent personal networks of industry representatives (1i & 1j) and government employees (1k & 1l).

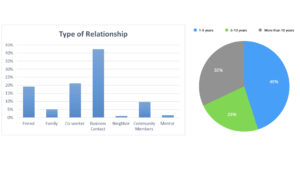

Type of relationship – Indicates the ratio of different types of relationships across social ties as determined by the survey respondents.

Length of Relationship – Chart indicates the relative length of relations described by respondents.

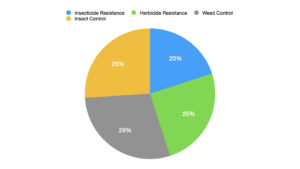

Topics discussed in typical interactions – Chart indicates the ratio of different general topics related to resistance management that are discussed in interactions between egos and alters.

Stakeholders reported different types of relationships in their personal networks around information and knowledge exchange. By far, the most common type of relationship our participants described having with their network ties was of a professional nature, either as a “business contact” (42%), or “co-worker” (21%). To a lesser extent, respondents classified some of their network ties as friends (19%), community members (10%), family (5%), mentors (2%) and neighbors (1%). Most of these relationships have existed for at least 5 years (55%) and a significant portion of those relationships are older than 10 years (32%) . Topics discussed in these interactions between different stakeholders were spread somewhat evenly across the 4 main categories of interest to this study. Weed control was reported as discussed at the highest frequency at 29%, followed by insect control at 26%, herbicide resistance at 25%, and insecticide resistance at 20%.

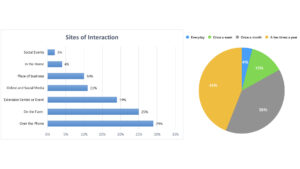

Sites of interaction – Chart indicates the different sites of interaction between egos and alters. Site of interaction is defined as a location where communication on resistance management-related topics takes place.

Frequency of Interaction – Chart indicates the general rate of information and knowledge exchange interactions between different social ties described by respondents.

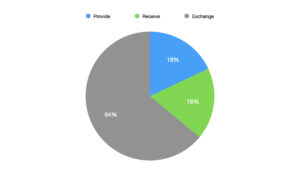

Information and knowledge flow – Chart indicates the ratio of how respondents described an interaction as either receiving, providing, or exchanging information and knowledge. Providing and receiving are considered one way interactions; exchanging is considered a two way interaction.

Stakeholders interact with one another about issues in pest and resistance management numerous times throughout the year at a number of different sites (see figure 5). The most common sites of interaction were over the phone (29%) and on the farm (25%). These sites were especially common with growers, with other stakeholders like extension agents and industry reps either fielding calls from growers, or traveling to visit them on their farms. Extension centers are also a common site for interactions (19%). Grower meetings and field days are hosted every year by extension on topics related to pest and resistance management and offer many opportunities for communication. They are attended primarily by growers, but industry reps, crop consultants, and governmental employees also participate. Online and social media (11%) and places of business (10%) were less common sites of interaction, and in the home (4%) and social events (2%) were the least common. Most interactions occurred at a rate of a few times a year (44%), or once a month (39%) (see figure 6). Some stakeholders reported interacting as frequently as once a week (13%) and a few everyday (4%) (see figure 6). The majority of these interactions were described as a two-way exchange of information and knowledge (64%), indicating that a respondent was much less likely to only receive (18%) or provide (18%) information to stakeholders in their personal networks (see figure 7). This suggests that stakeholders are engaged in two-way communication of information and knowledge across most personal network interactions.

|

Alters |

# Nodes |

#Ties |

Are they knowledgeable? (1-5) |

Trusted source? (1-5) |

Apply what you learn? (1-5) |

Aligned goals? (1-5) |

Aligned values? (1-5) |

|

Agent Alters |

16 |

18 |

4.93 |

5 |

4.63 |

4.5 |

4.44 |

|

Researcher Alters |

17 |

38 |

4.97 |

4.97 |

4.69 |

4.66 |

4.05 |

|

Grower Alters |

70 |

70 |

4.55 |

4.23 |

4 |

4.17 |

4.12 |

|

Industry Alters |

20 |

21 |

4.75 |

4.75 |

4.55 |

4.7 |

3.95 |

|

Crop Consultant Alters |

9 |

9 |

4.87 |

5 |

4.5 |

4.87 |

4.25 |

Alter characteristics and name-interpreting averages – Count of alter nodes across subgroups; count of ego-alter ties across subgroups; average likert scores for name-interpreting questions from the network survey data

Participants in our sample expressed high ratings for the knowledge, trust, applicability, professional goals and personal value alignment across the different sources of expertise in their personal network ties (alters) (see table 6 ; see table 1). This indicates that a high level of social capital exists within these relationships, which supports the potential for these different stakeholders to cooperate on challenges related to resistance management.

Live Interview Results Summary

Below are a summary of interview results from (n=22) participants across growers (n=7), extension agents (n=10), industry representatives (n=3), government employees (n=2).

Communication pathways and topics of discussionPromoting best management strategies, practices, and adoption “Now talking about the philosophy and theory of resistance management, we [extension] have preached that to death. For the last ten years we have been showing growers how it occurs and why it occurs, and I think we have made that point.” (Extension agent, ego #10) “Extension talks about the science side of understanding resistance a lot, and extension has drilled that into farmers. They know what is going to happen when they utilize the same herbicide over and over, or what will happen if they try to do things like cut rates or try and spray when the weeds are too big. We [extension] have show that the science proves what will happen if they do not follow what they are supposed to do… they [extension] are also speaking a lot and keeping farmers up to date on what they need to be doing, like recently a lot of farmers have started utilizing pre-emergent herbicides more often, whereas in the past they were more reluctant. So extension has done a good job of starting to get people used to pre-emergence, which is helping with resistance” (Extension agent, ego #6) “Anytime we have training we always listen closely to [extension specialist] and others who talk about new chemistries to help us further deal with this problem of herbicide resistance… but up until maybe the last year or so, the prevailing message has been that it is going to be hard to get new chemistries, so we would have to do a better job at managing with what we have, and to rotate chemistries… and I teach chemical applicator training, and that is one of the things we harp on a lot. I say ‘make sure you are rotating your herbicides to buy time for when that day comes, when you do not have these tools because resistance has fully occurred.” (Extension agent, ego #12) Seeking & sharing information on products usage and efficacy “I use my crop consultant – I've worked with them for years now – probably on a week-week basis during certain points of the season, or if there is an outbreak later in the year that needs to be addressed I will work with them a little bit more frequently… Extension research on resistance is useful, and I like to keep tabs on that, which is why I was at the [extension meeting]. But resistance, it is really more about big picture stuff for me, and I do not directly consult with [research] specialists more than maybe once or twice a year… If I really need some last minute information I can not get anywhere else, I will try my local extension agents.” (Grower, ego #9) “I generally reach out to extension people for information on general [resistance] management practices, like options for different chemical rotations, to get some idea of [economic] thresholds, and cultural practices I can use as a manager. I do that ahead of the season, usually, if I am trying to get some background on some things.” (Grower, ego #16) “Part of our responsibility is to make sure we are stewarding products properly by communicating with our customers the proper usage of these products. We have to utilize them in a way where we do not lose them, that is definitely a responsibility of companies like [company] to not launch products in a way that encourages improper usage, so we can maintain these tools for the future.” (Industry representative, ego #25) Monitoring trends and conducting research on local resistance evolution “That is where the values and practices of extension and our company align. We want to make sure we have the right tools and recommendations for our customers to produce good yields and keep their land productive, and extension keeps more of a finger on the pulse of where the resistance issues are at. So like, if there is a population of pigweed (Palmer amaranth) close by that is not being killed by a certain herbicide, I will probably hear about it at the extension meetings I attend… and I think that is the critical point of communication, between extension and industry, like we kind of ask ‘ok what is the state of the [resistance] problem’ and then we take that information and say ‘ok, lets see what other tools we have to fix that [resistance] problem.” (Industry representative, ego #13) “I follow a lot of the work being done by [researcher] on the Bt crops, and we are seeing that in the new research coming out, at least on the corn side, the non-Bt versus the Bt crops are not showing a lot of different in terms of yield, as long as you are managing insects properly…and the Bt crops do not seem to be controlling worms like they used to…I think we are starting to see some issues with resistance to those products.” (Extension agent, ego #4) “I’ve worked directly with [researcher] and their graduate student, and we together identified a new resistance in the area…What I did was mention it to [researcher], I said “I do not think this is a palmer [amaranth], I think its one of the grasses or something that is native to our area’ and he sent his graduate student out to collect it, and identified it as the one native to our area, and that we had resistance in that… and there are other examples of other agents who have done the same thing.” (Extension agent, ego #1) “Most of what I do is support research projects here at [research center]. My job is to communicate and coordinate between the center and extension or industry, whoever is performing the project, although most of the time here they are extension projects… a lot of the projects from industry are variety trials, but extension researchers do quite a bit with pest management. I think a lot of it is looking at different chemical products, chemical rotations with certain species in certain crops.” (Government employee, ego #8) |

Topics of Discussion: Example quotes on communication objectives and topics of discussion. Each quote is positioned under one of 3 the thematic categories of communication behaviors pulled from interview data: 1) promoting best management strategies, practices, and adoption 2) seeking and sharing information on product usage and efficacy 3) monitoring trends and conducting research on local resistance evolution

Concerns over herbicide and insecticide resistanceConcern for herbicide resistance “My biggest concern is that the research pipeline takes a long time to get from product discovery all the way to launching in to the market for customers to use. Its a very long process, and its a very expensive process for a company like [company]…Its a huge challenge that I see, and our customers, our farmers, they need more tools. We’re losing tools every day to resistance. We are also being regulated our of certain things, there is a lot of scrutiny on a lot of the herbicides and insecticides being developed currently… Its, I guess a fear of mine and a fear of everyone in the Ag industry, including farmers, that we are losing tools that we do not have replacements for.” (Industry representative, ego #13) “I would say my biggest concern is that once a weed becomes resistant, there are not many alternatives to turn to. And if it is resistant, and if prices to plant crops go up you will see a lot of people close up shop, and go bankrupt… Unfortunately, maybe not so much here, but when that happens you get farmers that commit suicide to get life insurance because they feel like they failed, you know you hear stories like that all the time. And so I think that is my major concern, is that as things lose efficacy and alternatives fall to the wayside that it will really hurt the agricultural community as a whole.” (Extension agent, ego 4) “I think my concern is a more general concern in that we are just not putting enough resources into agricultural research. Herbicide resistance, you know it is one of those things that we could tackle more effectively if we had more public attention and resources. We do not value public funded basic research in agriculture as much as we used to, I think that is the bigger problem.” (Government employee, ego #8) Concern for insecticide resistance Less of a concern “The concerns that comes to my mind right away is that we have insect resistance among corn ear worm in peanuts, but the varieties we grow now have such capacity to have bigger vines that the threshold for these worms have actually been increased because the certain percentage within corn earworms, or bollworms, or army worms, not all of them are resistant, maybe just a third of them. So we seem to be making out ok with the tools we have now, although [extension specialist] is recommending a change in how we utilize pyrethroids to control these insects… But I can not remember any time when someone has called me with a specific problem of insect resistance to the products they are using. I can not name one.” (Extension agent, ego 12) More of a concern “it is probably more of a matter of having fear of the unknown than the tangible. You know, the herbicide resistance weeds are there, visible, they are happening and I know how to handle them. And at least the resistant weeds have come to the farm in a way that I can track, and at a rate that I could observe. It wasn’t like suddenly they all popped up on the farm…Insects are more out of control and invisible to me. I may have a problem with a resistance insect and I won’t know that I do, and when it occurs it becomes apparent to me not because I scout, or a consultant told me, it will be that I spray, and it fails. So now I have a mystery to solve, and it's a movable thing that can happen in different fields over different seasons. Its an inability to pin those things down and have to rely heavily on someone else to identify it that makes those issues worrisome to me.” (Grower, ego #7) |

Pesticide Resistance Concerns: Example quotes for concerns related to insecticide and herbicide resistance pulled from the interview data.

Perspectives on learning interactions between stakeholdersFace-to-face interaction “When I talk to farmers face to face, I normally learn a lot. I have the resources provided to me as an extension agent, but they [growers] themselves are the ones that are actually applying the [pesticide] products and seeing how they work on their farm, and they understand what went well and what did not… I always learn a lot and usually relay that in some form to other farmers, because it is often a similar issue that they are seeing too.” (Extension agent, ego #6) “When I need recommendations for new problems, I usually go to extension. Like earlier this year, at the [extension event] I had conversations with [extension agent] about the billbugs that are becoming resistant to poncho, that can be a serious problem for us especially since we also lost our main over the top treatment. I am just not sure what our other options are for control, so I am working directly with them [extension] to think of potential solutions." (Grower, ego #7) “I think there is no substitute for meeting in person for developing a relationship with growers. When I came here out of college, in order to make a difference in what growers were doing recommendations really had to make a big difference. I had to really grow up in the position over time to make that difference. I learned from these people [growers], and they learned from me, and I had to be able to relax around them, and have those conversations about their operations that might challenge them to do something different. Its about having a rapport with the audience, and having the kind of relationships where I can be brutally honest about what I see and what they see.” (Extension agent, ego #12) Live demonstration and on-farm research “I held a scouting school this summer, which was a great opportunity for them [growers] to come and learn how to scout soybeans the right way, to learn what their thresholds were, and how to better preserve beneficial insects…One farmer that came, we scouted one of his fields during the demonstrations, and he had planned to spray it that afternoon. I said ‘do not spray it, see here all the beneficial insects you have?’ And that was a really good learning moment, where everyone got to see that even if you have stinkbugs, or some other pest, you have a whole lot of beneficial ones that are going to help take care of that. I know that he did not end up spraying.” (Extension agent, ego #3) “[Extension specialist] and [extension agent] are awesome about coming out to the field if you have a problem and doing on-farm research. They can do all the little plots that they want to on their own [at a research center], and they produce great information, but there is nothing like on-farm research trials. Those are real-life conditions.” (Grower, ego #15) “Getting research plots right out next to where we grow our crops brings it down to a field level and to an environment that we are used to managing. If everything stays on the research station, you know sometimes the weather and soil types just 20 miles away are completely different and the results are not necessarily applicable…I think most growers use it as an opportunity to gain insights and help them with their own operation. I think it is a win-win for everybody.” (Grower, ego #16) |

Perspectives on different social learning interactions – Each quote is positioned under one of the thematic categories of perspectives on social learning pulled from the interview data.

Building trust with growers“When you are going to go talk to growers, you have to develop that relationship. They do not expect you to have all the answers, they just want the truth. Fortunately, the more wise we get as we get older, the experience does eventually bring us the answers! Once you build that relationship based on honesty, trust, they will begin to listen to you.” (Extension agent, ego 10) “I spend a little more time on visits with [grower] helping them out with something [mechanical] on the farm, or just shooting the [expletive], scouting, or giving my product recommendations. But that's the important work of extension, I think. We have this professional relationship, but they are also my friend… So when I do have something important to say about managing certain things like resistance, they will listen.” (Extension agent, ego 4) “When you go to grower meetings, or field days, it is not all about selling the product… Of course we are there partially to promote our product lines but even if we do not talk to one farmer, they see that we are here, they see that we show up and we are invested in the community. Whether we sponsor it [extension event] or not it is about showing we care about the community. If we do not you will hear talk from different growers saying things like ‘oh, did you see that [company] wasn’t at the field day? Yea, they do not care about us or what's going on.’” (Industry representative, ego #20) “I think the biggest thing is just the willingness to go out and have a conversation, just go out and talk and meet them [growers] where they are. And something I have noticed that I do myself when I am talking to somebody, especially in terms of an extension agent trying to figure out what someone’s concern is, I do not just say ‘here is the problem, figure it out’ I am more like ‘here is what I am seeing, here is what I am thinking, please do not take this as one hundred percent what it is, because I am unsure, but if i had to guess right now here is what I’d say it is. Let’s do some testing to be sure.” That way, they understand where I am coming from, they do not get the impression that I am just blowing smoke up their rear end, or that I do not know anything, they see that there is some thought and care put in to how I make my recommendations.” (Extension agent, ego #5). “Growers of course know me as their [company] sales rep, but also as their neighbor, their friend, as a part of their community. I mean, I am in church with a lot of these guys every weekend, you know? I even do a little bit of farming on my own. They know that I am part of their community and want to see them do well.” (Industry representative, ego #25) “People know me as part of the farming community through my family. A lot of the growers know my dad, he farmed in the area for a long time. They know my family, that I have grown up in the area…so to me in agriculture, because it seems to be so community based, one thing I try to remember as extension agent is not always about being the smartest or knowing all the answers, or really about being right all the time. it is being able to talk to the farmer and communicate with them towards developing those relationships to where I am, as an extension agent, a trusted source of information. I think being a part of the community itself, it gets them to at least open the door, to at least listen to what I have to say. If they do not believe it, that is fine, at least I have put the bug in your ear, the thought in your head.” (Extension agent, ego #1) |

Building trust with growers: Example quotes on trust, influence, and social capital

|

Barriers to cooperation on resistance management Within the grower community “Cooperation is kind of defined as ‘here is one grower that is a bad actor and he needs to do better and all the rest of us are putting pressure on him to keep him from bringing things into the neighborhood and spreading it around.. but after it becomes more of a ubiquitous problem, then the same people that may have been pointing the finger now are focused on addressing the problem on their own farm. If there is a pariah, then we can jump on him, but if it is everybody we are just going to co-exist with the problem.” (Grower, ego #9) We are competitors, but we are also neighbors and to that extent we want them to succeed as well as us…We are independent though. We do not collaborate a lot or work together on certain things but we also do not do things to intentionally undercut our neighbors, either… I do not think its that we do not want to work together, I think it is more that we have different management styles, different numbers of acres, different types of equipment, different labor, and often different pest challenges in their operations than we face in ours.” “I think there is potential for us [growers] to be watching the horizon together, but less potential to be watching the property line. I think things that are of a general nature coming from way off giving us [growers] all a heads up on something are ok, but in terms of someone saying ‘I’ve got this problem in my crop, you need to be on the lookout of seeing it down the road in your crop’ we might not be that magnanimous or cooperative.” (Grower, ego #19) Between extension and industry “When it comes to extension recommendations, and industry product recommendations, where the problem arises is if you are a dealer, and your most profitable product is not the one that extension and others recommend, you are still going to recommend that most profitable product. And there may not be anything wrong with it, it might be a great product. But then when you start getting in to resistance management then you have to start looking at some of those issues as an agent and say ‘hey, there are better things out there, here is what you need.’” (Extension agent, ego 10) “A lot of farmers go to the company rep that they buy the most stuff from, and the company rep their job is to sell so they are going to go out every couple of weeks and talk to the farmer. I know they are all aware of it [resistance] and they want to make sure the farmer does well, I do not think I’ve met a single one that cares only about money and profits, but at the same time if information only comes from the company, they are only going to care about selling their product. They will recommend the rotating, they will recommend to use something else, but I fear that some of them are saying ‘my product is the best product’ whether it is or not, and do not have any proof of this. I’ve heard the rumors of not quite the best done research to prove their product is the best, in some way shape or form from company trials.” (Extension agent, ego #18) |

Perspectives on cooperation: Example quotes that illustrate potential barriers to cooperation on resistance management within the grower community, and between extension and industry.

Discussion

Successful herbicide and insecticide resistance management requires some degree of collective action to properly coordinate best practices across diverse local contexts to preserve pest susceptibility at the landscape level. Translation and adoption of relevant knowledge into local networks of stakeholders is key to the success of coordination, but not much is understood about local stakeholder relationships surrounding this information and knowledge exchange. In this study, we adopt a qualitative network analysis under an agricultural innovation systems framework to explore social relations around information and knowledge exchange. Our goal was aimed at studying social learning and social capital within the personal network ties of different stakeholders to build an understanding of how relationships influence the translation and adoption of resistance management knowledge. Our analysis produced key findings on the different structures of stakeholder personal networks, the nature of social learning interactions, and how trust and reciprocity are built in relationships around information and knowledge exchange. Our findings on personal networks, social learning, and social capital suggest insights for enabling collection action, as well as some potential barriers.

Stakeholder’s personal networks demonstrated high connectivity across different forms of expertise, demonstrating the potential for social learning. Personal network interactions are reciprocal exchanges of information and knowledge, suggesting that there is potential for mutual benefits in communication between different stakeholders. Results also show that there are high levels of mutual concern around the issues of resistance, especially herbicide resistance. Mutually beneficial interactions around these issues of concern can stimulate future social learning interactions (de Kraker, 2017 ; Reed et al, 2010) between stakeholders, and build capacity for collective action. Results also suggest that social ties are anchored in a high level of social capital, as stakeholders consistently rate other stakeholders as knowledgeable, trustworthy sources of expertise. Building social capital was of particular importance in extension-grower, and industry-growers relationships. Perceptions on how to build social capital in these relationships revolved around the importance of honest communication and maintaining a consistent presence in the community.

Stakeholder perceptions on social learning suggested that in-person demonstrations and participation in research projects were the most effective mechanisms for changing behaviors and decision making. Our data showed that partnerships between extension agents, researchers and growers were very effective at building capacity for participatory research. Some growers suggested industry partnerships were also effective, although this theme was not as strong in our data. Participatory research projects could be a strong option for enabling collective action in our case context, because they support social learning interactions (Neef and Neubert, 2011 ; Kroma, 2003) and the building of trust and reciprocity between different stakeholder groups (Ingram et al, 2020 ; Wood et al, 2014). Extension’s role as a boundary organization (Carolan, 2006) is well positioned to support more of these projects, and based on our data we speculate that extension agents would play key roles as coordinators.

Our findings also suggested some potential barriers to collective action. First, there was a glaring lack of personal network connections between growers in our study. Low levels of network connections between growers indicate little opportunities for growers to learn from one another on issues related to resistance management. Interview data from our grower participants suggested that, overall, growers express a reticence to cooperate with other growers on issues related to pest and resistance management due to a lack of trust in other growers, and the perception that growers are in competition with one another for information. This suggests that building collective action between growers might be more difficult in this context, and might require the facilitation by trusted non-grower stakeholders. Second, perspectives from extension stakeholders suggested that extension and industry might be in competition to influence growers on resistance management issues. This potentially creates issues for sharing information and coordinating practices on resistance management, as extension and industry could exert confounding influence on the decision making of growers. Collective action will likely not work if local industry representatives and extension stakeholders struggle to collaborate.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

- Consultations ( 10 Expected)

- Over the course of research, I plan on consulting with 5 extension agents and 5 extension/university researchers on resistance management norms, practices, and network science. -- (Completed)

- Educational Tools (1 Expected)

- Research will culminate in a comprehensive project report (white paper) that will provide recommendations for the social coordination of resistance management practices across different farming systems in Eastern North Carolina. The report will not only act as an informational resource for growers, but also a toolkit for conducting further research and outreach activities through extension. The report will be distributed to all extension centers upon completion, and passed along to growers via email. -- (Forthcoming)

- Journal Articles (3 Forthcoming)

- Publication on social networks and resistance management in agricultural systems in agricultural science/social science journal (e.g. Agricultural Systems ; Journal of Rural Studies ; Journal of Agriculture and Human Values)

- Publication on stakeholder perspectives on pesticide resistance (e.g. Journal of Agriculture and Human Values, Society and Natural Resources, Ecology and Society)

- Publication on methodological approach in extension journal (e.g. Journal of Agricultural Extension, The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension)

- Webinars, Talks, and Presentations (3 completed; 1 expected)

- Presentation at Society for the Social Studies of Science conference -- Completed October 2021

- Presentations at NC State (e.g. Genetic Engineering and Society Center; Graduate Student Research Symposium) -- Completed Spring 2021

- Talks through NC State Extension at Growers meetings in Spring 2022 -- Completed February - March 2022

- Presentation at Agriculture and Human Values conference -- Upcoming May 2023

Participation: 10 Extension Agents, 10 Growers, 3 Industry representatives, 2 Government employees

- 25 participants for questionnaire

- 22 participants for live interview

Project Outcomes

This project has generated a starting point for understanding the social conditions of pesticide resistance management in Eastern North Carolina. We have considered how different elements of social networks, stakeholder perspectives, and norms of communication affect the ability for different stakeholders to cooperate on issues associated with resistance management. Our work is preliminary, in the sense that it was conducted with a small sample size, and gestures towards future questions and challenges that could form the basis of future research projects. Other researchers exposed to this work in the forthcoming journal articles or through the SARE web repository should find several avenues and possibilities for thinking through social challenges related to coordinating resistance management practices across stakeholder networks. For farmers, this work provided an opportunity for voices and perspectives to be heard on a topic that farmers do not get asked about very often. Including farmer voices in research such on resistance management will promote a greater incorporation of their values, concerns, and knowledge into future practices of social coordination. As stated, this work acts a starting point to exhibit farmer perspectives at the center of future practices in Eastern North Carolina. Future work in this region can pick up on this preliminary project and continue to build robust frameworks and practices that ensure the best outcomes for farmers as active and central members of resistance management knowledge networks.

Final Summary

Insect pest and weed management are a set of practices situated in complex systems. The communication networks surrounding these activities are inundated with vast amounts of information that compete for attention from the on-farm decision makers. Priorities must be set on how to best control pests in the midst of other cost/benefit decisions, and growers are sometimes caught in the middle of misaligned & sometimes conflicting recommendations from scientific authorities in industry and extension.

Trust is a huge factor at play in farmers personal knowledge exchange networks, and is complimented by a frequency of interaction metric. The relationship between how often a grower is exposed to a certain idea, or piece of information is an important factor in whether or not that idea holds influence in a growers practices. In addition, extension agents and specialists consistently receive some of the highest trust ratings in this study, and are perceived as the most knowledgeable sources for the latest information on best practices for pest management. However, the frequency and exposure to extension agents and specialists for growers is much less than their exposure to their industry contacts due to a lack of resources compared to industry. Valuable scientific knowledge generated by extension often goes unused due to a lack of interaction with it, and it can therefore take a long time for extension knowledge on complex issues like herbicide and insecticide resistance to take hold in a population of growers.

Some of the most meaningful interactions between growers and extension, or growers and industry are through collaborative research projects. Growers report very positive knowledge gains from working with researchers on mutual questions of concern, and extension especially sees collaboration as a key to effective communication.

Farmers are far less ready to engage in a cooperative system of pest management than anticipated. While the seeds of "co-production" are present in central and eastern North Carolina, many barriers to cooperative approaches still exist. One example is that many farmers perceive of their fellow growers as "competitors" and don't readily share out information related to their individual pest management practices with other growers. This is a preliminary hypothesis, and not answerable in this study, but it seems that a combination of stigma and "trade secrets" keeps communication between farmers limited. Stigma, in the sense that farmers may fear a kind of social retribution or ridicule if they do not manage certain pests effectively. Trade secrets in the sense that farmers who do manage pests effectively don't want to keep that competitive advantage over their fellow growers.

Growers have different means to implement best management practices, and for some, the ideal practices are either too expensive or too risky for their bottom line. Economic sustainability is a key issue here, especially with prices for inputs, insecticides, and herbicides continually rising. Without a shared pool of resources to draw upon, it's unlikely that a grower community will engage in a cooperative approach. Moreover, a shared pool of resources would have to be provided externally for growers who don't have the financial means to implement best management practices to align with those who do.

Final Recommendations:

There are three general institutional recommendations drawn out of this based on this work from Eastern North Carolina:

- Increase capacity for extension to perform, publish, and distribute information and knowledge networks in agricultural communities. More funding is needed to retain good agents and researchers who contribute uniquely unbiased knowledge that is critical to farmers making decisions about pest management practices.

- Enhance the ability for growers to participate directly in extension research projects. Incentivize extension to promote even more direct participation in research projects concerning pest and weed management through 1) field days 2) on-farm trials

- Consider directly incentivizing and supporting cooperative approaches through institutional messaging from universities and federal agencies. Providing a common framework for cooperative management in addition to informational resources for growers to draw upon can provide a starting point for building cooperative frameworks in local contexts.