Final report for GS22-260

Project Information

Pesticides are widely used to prevent the loss of crop yields to insect pests. However, pesticides can also have detrimental effects on beneficial insects that contribute to successful crop pollination. While there has been much recent interest in the effects of pesticides on bees, the majority of this research has focused on honeybees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebees (Bombus spp.), with experiments largely conducted under lab conditions. However, other bee species are also critical pollinators to many crops. The majority of the 4,000 bee species in North America are solitary and ground nesting, and in Cucurbita crops (pumpkin, squash, zucchini) the specialist ground nesting squash bee (Eucera pruinosa) provides the majority of the pollination services. Recent studies have shown that insecticide exposure in semi-field experiments can reduce the reproductive success of squash bees, but how pesticide exposure impacts their foraging behavior and ultimately, population numbers, is not known. If foraging behavior or abundance is negatively impacted by exposure this could have major consequences to pumpkin production. In this study I will assess the influence of pesticide exposure on squash bee communities across sites in central Texas. Specifically, I will address how pesticides impact squash bee abundance and if the effects of exposure to two commonly used insecticides (thiamethoxam and bifenthrin) can be predicted based on their toxicity to honeybees.

Aim 1: Assess how pesticide exposure and landscape composition impact squash bee abundance . It is critical to understand exposure across the community, but especially for the key pollinator, E. pruinosa; this will be done To understand variation in pesticide exposure across sites we will compare the pesticide residues detected in the bees themselves to the residues detected in the pollen and nectar from the plants, soil, whole bees (squash bees and honeybees), and bee guts (squash bees and honeybees) from each site. Pollinator surveys on cultivated pumpkins were conducted at 17 farms in West Texas three time points during the blooming period. Specifically, we will compare how bee abundance is predicted by a traditional hazard assessment that only considers the concentrations of pesticides in the crop nectar versus a hazard assessment that additionally considers exposure through pollen and soil (Chan et al., 2019). This allows us to identify the most important routes of exposure by comparing these two different hazard assessments to our measures of pesticide residues in individual bees, to see what routes of exposure are most important to consider to prevent population declines.

Aim 2: Experimentally test if exposure of two commonly used insecticides have lethal or sub-lethal effects on squash bees. The effects of insecticides on pollinators are typically tested using honey bees and bumblebees; we have adapted established protocols from those species to test how field realistic exposure of two commonly used insecticides affects squash bees. Specifically we will address if propensity to forage is negatively impacted by field realistic exposure to thiamethoxam and bifenthrin with a proboscis extension response assay that can be used on wild caught bees. This will allow us to test whether insecticide effects on these responses are generalizable beyond model species.

Research

Aim 1: Assess how pesticide exposure and landscape composition impact squash bee abundance and identify probable routes of pesticide exposure.

Study design: We worked on 17 farms in west Texas that all grow pumpkin. Every site will be visited 3 times during the blooming period from May to August. During the second of the three visits we collected samples of each pollen & nectar, soil, and bees (A. mellidera, X. strenua, and X. pruinosa) which were sent to AGQ labs in Oxnard, California to be analyzed for pesticide residues with a paired LC/MS GC/MS analysis. Landcover surrounding each site was calculated with ArcGIS using CropScape data layers.

We conducted visitation surveys during each of our three visits to the sites. Surveys consisted of walking 44m transects for 20min and recording the identity of each bee that is observed landing on a flower as has been done in other studies of the pollinators that visit pumpkin (Petersen and Nault, 2014).

We collected our pollen and nectar from flowers during this second site visit, when the plants are likely to be in the fullest bloom, and so are a major floral resource for the bees. A ~10g soil sample was taken from the center of the field (approx. 5cm deep) to be consistent in the location of sample collection from each site and since squash bees are known to nest in crop fields (soil sampling per site as in Chan et al. 2019). All samples for pesticide residue analysis were stored at -80 degrees until they were shipped to AGQ labs. We will run generalized linear models (GLMs) to assess the impact of surrounding agricultural landcover, floral density, and pesticide hazard on community level pollinator richness and pollinator abundance. We will calculate hazard quotient based on the residues detected to inform if the risk to bees is actually below the EPA level of concern at our sites (negligible risk to mortality as 5% of the honeybee LD50) when exposure only through the nectar is considered compared to when pollen and soil exposure are factored in as well.

Aim 2: Experimentally test if exposure of two commonly used insecticides have lethal or sub-lethal effects on squash bees.

We collected squash bees (X. pruinosa) directly off of Cucurbita sp. flowers across 6 sites around Austin, TX while they were foraging (between approximately 6:30am - 8:30am) throughout May and June in 2021 and 2022 and put into a cooler with ice packs. All sites were either natural areas or community farms that did not use pesticides, to minimize potential exposure to pesticides before our assays. We brought the bees back to the lab and put them in the dark in modified 2mL eppendorf tubes, which had a screen mesh over one end for air flow and a glass tube feeder with 30uL of 10% (w/w) sucrose solution.

The following morning we recorded mortality, and all live bees were secured into a modified 1mL eppendorf tube harness such that the bee’s head and first pair of legs were free. We then randomly assigned bees to treatment groups representing males and females equally across the treatment groups. For all experiments we had three groups; bees treated with thiamethoxam (THX), bees treated with bifenthrin (BIF), and untreated control bees. The average concentration of thiamethoxam detected in pumpkin nectar following seed treatments has been measured at 17.6 ppb, while bifenthrin has been detected at an average concentration of ppb in Cucurbita nectar (Dively and Kamel, 2012) and both of these concentrations are below the level of concern defined by 5% of the honeybee LD50, so we will feed bees 4 microliters of 10% sucrose solution at these concentrations, in addition to a set of control bees that are fed untreated sucrose solution as our "medium" dose group. One hour after dosing we will record if there is any mortality and then the bees will be restrained in tubes to undergo a sucrose responsiveness assay modified from Carlesso et al. 2020, which will allow us to determine if treated bees are less responsive to increasing sucrose concentrations, which is a proxy for foraging propensity (Scheiner et al., 2004). We additionally added in a "low" dose based on the lowest concentrations of thiamethoxam detected in pumpkin nectar following seed treatments (Dively & Kamel, 2012), and concentrations of bifenthrin detected in pumpkin nectar of similar toxicity relative to the honeybee LD50 (Frazier et al. 2015).

To better understand the relationship between the honeybee LD50 and toxicity to other bee species we also added in a "high" dose treatment that was not necessarily intended to be field realistic but to be the same in terms of relative toxicity compared to the honeybee LD50, both insecticides were fed to the squash bees at a dosage that was 20% of the honeybee LD50. If the honeybee LD50 can be scaled to accurately predict toxicity to other bee species we would have expected no difference between the two insecticide treatment groups.

The current risk assessment framework relies on defining what pesticide concentrations in nectar minimize acute lethality in honeybees, but these are not the only bees providing pollination services to agricultural systems. Pumpkin is a pollinator dependent crop that is primarily pollinated by the solitary squash bee (X. pruinosa), and it is unknown to what extent this risk assessment framework actually prevents negative effects on these bees. Additionally, it is critical to assess if a risk assessment framework based on acute lethality actually represents a level of risk that minimizes losses to pollination services due to effects on the abundance of important pollinators and the pollinators’ foraging behavior.

Aim 1: Assess how pesticide exposure and landscape composition impact squash bee abundance and identify probable routes of pesticide exposure.

Overall, we detected no pesticides in any of our nectar or pollen samples, but detected pesticides in 100% of our soil samples (between 1-8 detected per site). We detected the fungicide Quinoxyfen in our whole male bees (X. pruinosa and X. strenua), in our whole honeybees (A. mellifera), and in the guts of the males of one squash bee species (X. strenua), but we did not detect anything on our female squash bees. This shows that risk assessment based only on consumption of nectar would lead to different estimated risks than if exposure via soil were also included.

The pesticides we detected across all samples were not primarily based on what was applied to manage the pumpkin fields. The growers shared that they applied the insecticide Bifenthrin, and two fungicides (Azoxystrobin and Myclobutinil) but these were poorly represented across our samples. In one soil sample we detected Myclobutinil, and in one other we detected Bifenthrin, but all other pesticides detected were not applied to manage pumpkin. This suggests that the risks posed by the pesticides applied to pumpkin likely do not capture the true pesticide risk posed to bees at the sites.

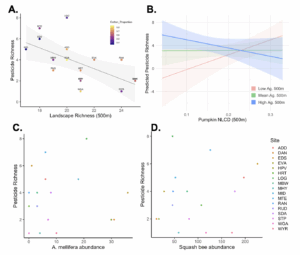

We are finding that the surrounding landscape composition is important in predicting how many pesticides we detect in the soil, and the cumulative toxicity of those pesticides (measured in hazard quotient based on honeybee LD50 data available through the EPA ECOTOX database). Landscapes with more landcover categories 500m surrounding the site (landscape richness) have fewer pesticides detected (pesticide richness) (Fig. 1A). We also found an interaction between the amount of surrounding agriculture and amount of surrounding pumpkin 500m around a site, when surrounding agriculture is low we are finding that more surorunding pumpkin predicts more pesticides but that when surrounding agriculture is high more surrounding pumpkin predicts fewer pesticides detected in the soil (Fig. 1B).

We did not find that the number of pesticides detected in the soil, or the hazard quotient of the soil pesticides predicted bee abundance for either honeybees (Fig. 1C) or squash bees (Figure 1D). Future work could explore if agriculturally intensive systems like these impose selective pressures on the bee populations such that only bees that can tolerate pesticide exposure persist.

Aim 2: Experimentally test if exposure of two commonly used insecticides have lethal or sub-lethal effects on squash bees.

We have conducted the sucrose responsiveness assays with our 'low' dose group (based on lowest concentrations of thiamethoxam and bifenthrin detected in pumpkin nectar (Dively & Kamel, 2012; Frazier et al. 2015)) at 0.032ng of thiamethoxam per bee, and 0.017ng of bifenthrin per bee. Our 'medium' dose group was based on the average concentration of thiamethoxam detected in pumpkin nectar (Dively & Kamel, 2012) and a dosage of bifenthrin that was matched to be the same percentage of the honeybee LD50 as thiamethoxam due to limited data about bifenthrin residues in pumpkin nectar.at 0.074ng per bee of thiamethoxam and 0.157ng per bee of bifenthrin.

To better understand the relationship between the honeybee LD50 and toxicity to other bee species we also added in a "high" dose treatment that was not necessarily intended to be field realistic but to be the same in terms of relative toxicity compared to the honeybee LD50, both insecticides were fed to the squash bees at a dosage that was 20% of the honeybee LD50. If the honeybee LD50 can be scaled to accurately predict toxicity to other bee species we would have expected no difference between the two insecticide treatment groups.

Figure 2: sucrose responsiveness data

Although our analyses are ongoing, preliminarily we find no differences across groups of bees from the 'low' dosing scheme (Fig 2A), we do find a potentially interesting difference in responsiveness only at 50% sucrose in our 'medium' dosing scheme (Fig 2B), and most surprisingly we found complete mortality in the thiamethoxam group at our 'high' dosing scheme (Fig 2C).

We expected all of our doses to only elicit sublethal effects to sucrose responsiveness as none were approaching high levels of toxicity compared to the honeybee LD50. Most interestingly, we find a dramatic difference between exposure to thiamethoxam and bifenthrin at this 'high' dose as our bees dosed with bifenthrin did not differ from our control bees in terms of sucrose responsiveness (and mortality - as there was none). This could have implications for how reliably we can apply the honeybee LD50 across species even when we include scaling factors that are meant to be conservative.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Science Under the Stars Outreach talk

Participation summary:

Talks: I gave an invited talk about the preliminary sucrose responsiveness data which was collected for aim 2 of this project at the Entomological Society of America conference. The number of 'agricultural professionals' that I listed as participants above is an estimate, but it was a full room for the talk and I know a subset were employed with Bayer and other similar companies that play a large role in agricultural practices.

In October (2025) I gave a one hour seminar talk to the University of Texas at Austin’s ecology seminar series “Ecolunch” summarizing our current results for both aims of the project.

This year I will be presenting our preliminary results associated with aim 1 at the Entomological Society of America conference on Nov. 10th 2025.

Other education activities: I was the graduate student coordinator for a program at UT Austin that brings high school students onto campus twice per week during the school year to get involved in research and generally demystify the research process, and during the course of the work I've been doing with squash bees I have had two high school interns help with sample processing and measuring bee body size.

I also gave a talk at Science Under the Stars in collaboration with the Texas Science Festival, which was a 1 hour public talk about bee behavior and pesticide effects on bees (including parts of this project).

We have recently finalized the analyses for the sucrose responsiveness data and are intending to submit the manuscript to Apidologie. We are currently working to finalize the analyses for the data associated with aim 1 and intend to submit this for publication as soon as possible as well.

Project Outcomes

The results from the project suggest that the risks that pesticides pose to bees may not be well captured via exposure through nectar, and in highly agricultural systems the pesticides present at the site may be better predicted by landscape level land use as opposed to how a particular field is managed. We also show that the honeybee LD50 is likely not representative to other species, even if scaling factors are used to try to capture risk to smaller bodied species. Both of these outcomes suggest that for pollinator dependent crops it is likely important to consider multiple routes of exposure, the surrounding landscape, and species specific sensitivity to pesticides when possible to protect yields and bee populations broadly.

Throughout this project we learned about the practical constraints and considerations that impact grower management strategies. For example, while the West Texas pumpkin system does rely on pest monitoring to time application of insecticides, the specific timing is constrained by when the pilot is available for aerial sprays and is more cost effective when multiple fields can be sprayed at a time.

Figure 1: landscape effects on the number of pesticides detected in the soil, and the lack of relationship between the number of pesticides detected in the soil and bee abundance for honeybees (A. mellifera) and squash bees (X. pruinosa & X. strenua)

Figure 1: landscape effects on the number of pesticides detected in the soil, and the lack of relationship between the number of pesticides detected in the soil and bee abundance for honeybees (A. mellifera) and squash bees (X. pruinosa & X. strenua)