Final report for GW16-033

Project Information

The goal of our project was to characterize communities of non-bee pollinating insects on organic farms and urban gardens in the Puget Sound region of western Washington State, and examine their interactions with bees. To achieve this, we measured the abundance and diversity of flowering plants on 35 farms in 2015 and 2016, and monitored insect visitation to these plants. While these plants were visited primarily by bees, we also observed frequent visits from one key group of non-bee insects, syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Other groups of non-bee pollinating insects, including moths and butterflies (, were rare. Syrphid flies visited the reproductive structures of 83% of the different flowering plant species in our farms, suggesting they may be important pollinators. Moreover, syrphid flies visited 3 of the 4 flowering plant species that were not visited by bees, suggesting that these two groups have complementarity in terms of pollination services. Syrphid abundance was similar on farms location in urban compared to rural locations, but increased with greater floral diversity on farms in either type of landscape.

Our research goals were paired with an extensive outreach and education program, whereby we disseminated information to hundreds of growers, educators, and researchers of the importance of these non-bee pollinating insects through a wide array of forums. This outreach has resulted in the development of a pollinator monitoring team of growers and citizen scientists contributing to an extensive observational study aimed at pollinator conservation in the western Washington region. Using the data collected during this project, to date we have published a peer-reviewed guide to native pollinators of western Washington, including non-bee pollinators. We are in the process of developing a scientific publication as well on non-bee pollinating insects that will be submitted in the fall or early spring 2018.

Introduction

Insect pollinators are essential for the production of 70% of the most widely consumed global food crops (Klein et al., 2007). Historically, it has been assumed that honeybees and native bees provide the majority of these pollination services (Garibaldi et al., 2013). Many non-bee insects such as moths, butterflies, flies, wasps, and beetles also function as pollinators, however (Garibaldi et al., 2013; Rader et al., 2009). In addition, non-bee insects might indirectly impact pollination by interacting with bees (Romero, Antiqueira, & Koricheva, 2011). However, the ecological impact of non-bee insects, and whether they contribute to sustainable crop pollination on farms, has rarely been studied. Research on the impacts of non-bee insects on pollination services is thus critical, especially considering the recent, widespread declines in honeybee and native bee populations (Listabarth, 2001; Rader, Howlett, Cunningham, Westcott, & Edwards, 2012). If non-bee insects provide substantial pollination services, or increase the pollination efficiency of bees, then conserving these species could improve the stability and profitability of many agricultural systems (Crowder, Northfield, Strand, & Snyder, 2010).

Project Objectives

- Our project objectives were as follows

- Characterize communities of non-bee insects on diversified organic farms and their direct contribution to crop pollination

- Examine whether non-bee insects indirectly affect crop pollination by bees

- Educate farmers and the public on the role of non-bee pollinators in sustainable farming

Cooperators

Research

- Objective 1: Characterize communities of non-bee insects of diversified organic farms and their direct contribution to crop pollination.

(i) Sub-objective 1a: Sample non-bee insects communities on diversified organic farms

We sampled 35 farms twice each season for pollinators by deploying pan traps, blue vane traps, and aerial netting. We set out traps for an 8-hour period at each farm, twice per year. We also spent a total of 30 minutes per visit, at two visits per year walking through the farm fields and collecting insects visiting flowers using an aerial insect net. Finally, using geographical information systems cropscape land cover data, we have separated the farms in our system into urban and rural categories (dictated by land cover surrounding the farm being highly developed or not highly developed). We measured landscape data to look at whether farming in an urban or rural environment had any effect on pollinator diversity and the abundance of non-bee insects.

(ii) Sub-objective 1b: Determine structure of plant-pollinator networks on farms

During the summers of 2015 and 2016, we sampled the floral diversity and pollinator diversity of a network of farms in western Washington. We measured floral diversity by spending one hour walking a serpentine pattern through the farm site, dropping a meter square, and counting and identifying all of the flowering plants within that square, then repeating every few meters. We recorded the abundance of each type of flowering plant. By using this approach, we could apply an even sampling method to fields of uneven size. To measure pollinator diversity, we monitored pollinator visitation on flowers over the course of one hour, in a similar fashion as the floral diversity. We walked a serpentine pattern, stopping every few meters, and spent one minute recording the type of organism visiting a flower. This portion of our data was non-destructive, and so the pollinator groups were identified to order level (ie Hymenoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera, etc). We repeated this at each farm twice per visit, and during two visits per season. We also recorded the type of flower receiving the visit.

(iii) Sub-objective 1c: Assess pollination efficiency of non-bee species in the field

Identification of non-bees took much longer than anticipated, so we were unable to identify which species of non-bee pollinator might have been most abundant and effective at delivering pollination services. However, using the data collected in sub-objectives 1a and 1b, we were able to track which flowering plants non-bees were visiting and how they were contributing to pollination, and how their contribution complemented bee pollination. These data show in good detail the foraging patterns of various non-bee species, and show clearly that syrphid flies are the most effective pollinators in our systems.

- Objective 2: Examine whether non-bee insects indirectly affect crop pollination by bees.

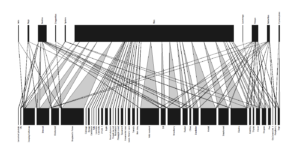

- Initially we had planned to plant cucumbers and measure pollination at the Tukey Orchard in Pullman WA. However, after analyzing the data from our first year of sampling, we did not record any flies visiting cucumber (Figure 1). Although there were plants commonly visited by both flies and bees, many of these plants are considered weedy species (examples: henbit, creeping buttercup, wild mustard) and we determined that this would not be relevant to growers’ interests. Therefore, we focused our efforts in analyzing the data collected in objective 1 to discover potential effects in direct pollination. We also expanded our initial proposal to explore the network structure of non-bee insects. This allowed us to get at the question of how non-bee species interact with bees. While we were unable to directly observe interactions between these species as we had originally planned, our network approach is a powerful tool to visualize the interactions between bees and non-bees in real-world field settings.

- Results and Discussion

- Objective 1: Characterize communities of non-bee insects of diversified organic farms and their direct contribution to crop pollination.

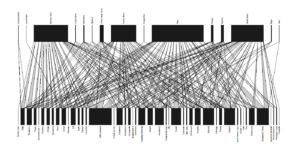

In 2015, we extensively sampled the entire pollinator community, with the goal of characterizing the non-bee pollinator community. We recorded a total of 2,405 insect or spider visits to the reproductive structures of flowers. Bees of all types (honey bees, bumble bees, green bees, small bees, and other large bees) made up 1,458 of these visits, followed by flies with 811 visits. Visits by other groups of non-bee insects were relatively rare, although we did detect visits to flowers from wasps, lacewings, spiders, butterflies, dragonflies, beetles, and ants. We recorded a total of 46 different types of flowering plants on the farms sampled (Figure 1). Because the total visitation by insect groups other than bees and flies were extremely low (only 109 out of 2,405 visits observed - 5%, Figs. 1, 3), in 2016, we eliminated other insect groups from our study and focused on the flies. Syrphid flies made up most of the flies seen on flowers, which aligns with many publications on non-bee floral visitors (Rader et al., 2009).

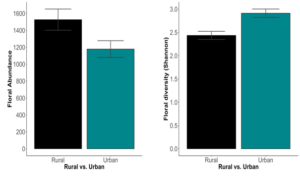

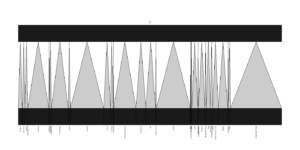

Over the 2015 and 2016 sampling seasons, we observed 18 different species of syrphid flies at our sites. We compared syrphid abundance with the floral diversity at each of the 23 farms that were visited in both years. As mentioned above, flies were seen visiting 38 of the 46 flowers recorded, suggesting these flies are generalist pollinators. This is reflective of previously published data (Haenke et al., 2014; Rader et al., 2012). We found that an increase in floral diversity resulted in a decrease in syrphid abundance (Negative Binomial General Linear Model [NB-GLM], z= -2.264, p= 0.024). We thought this might be due to landscape type (rural or urban), because we did find significant floral abundance and diversity differences between urban and rural landscape types (figure 2). However, syrphid abundance was not significantly affected by landscape type (NB-GLM, z = -0.88, p=

0.38). The last piece of data we analyzed was syrphid abundance each year we sampled. We found that there were a significantly higher number of syrphids sampled at our farms in 2015 compared with 2016 (NB-GLM, z= -2.07, p= 0.039). We looked at weather and precipitation data from the WSU AgWeatherNet service and found no differences in either the average air temperature (mean difference = 1.1 ± 8.165, two sample t-test, t22= 0.28, p= 0.78), or the average precipitation (mean difference = 0.08 ± 2.49, two sample t-test, t22= -0.07, p= 0.94). We are unsure why the syrphid abundance differed between the two sampling seasons, and suggest this as an area for future study.

Objective 2. In our effort to measure the non-bee impact on pollination, we recorded all insects seen on the reproductive structures of flowers and noted 811 fly (order Diptera, fig. 2) visits on 38 of the 46 recorded flowering plants in our system. Bees were seen 1458 times on 41 of the 46 plants. Notably, 4 of the plants not visited by bees were visited by flies (fig. 1). Three of these plants were crop plants being grown for commercial sale (kale, lily, and pea), one of which benefits from insect pollination (pea). While we didn’t measure the direct pollination efficiency of the flies, the observation that flies potentially filled a pollination gap that was not being met by the bees indicates that syrphids may be playing an important role in overall pollination services on the farms.

Research outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

- Education and Outreach – we had a diverse education and outreach program intended to share information about non-bee pollinators to growers, citizen scientists, and other interested parties. This program took several forms, as described below:

Pollinator guide - Working with collaborator Elias Bloom (fellow PhD student in the Crowder lab), our lab has published a peer-reviewed field guide to pollinators in western Washington. This guide includes diagrams, photos, and descriptive characters for bees and non-bee pollinators. It also describes the types of flowers each group visits, and techniques for monitoring on farm or in urban gardens. We have used this guide as a teaching tool at over a dozen field days and citizen science workshops. The guide, titled “A Citizen Science Guide to Wild Bees and Floral Visitors in Western Washington” was published by the WSU Extension Research Exchange and is available for via the web: https://research.libraries.wsu.edu:8443/xmlui/handle/2376/11915.

Professional talks - Olsson delivered multiple lectures in academic settings regarding some of the data collected as part of this project. She was an invited speaker as part of the University of Idaho’s Pollinator Seminar series in September of 2015, and spoke about native pollinators including non-bee pollinators. She also presented the 2015 data during the Washington State University Entomology department colloquium seminar series in April of 2016. In 2015 and 2016, Olsson presented at the national meetings of the Entomological Society of America. These presentations focused on findings from this study and related studies conducted by Olsson.

Webinars- Olsson participated in two webinars over the course of this project. Each has been hosted by eOrganic, and have been attended by close to 200 participants. The YouTube videos of the webinars have been watched hundreds of times since the initial webinar. During these webinars, Olsson discussed non-bee pollinating insects and their contributions to farming systems.

Field Days and Citizen Science Project- Olsson has been working with Bloom on field days and a citizen science campaign in the greater Seattle area since 2014. During these field days and citizen science workshops, Olsson discussed the importance of pollinator biodiversity, and taught workshop participants how to monitor and identify some of the more common non-bee pollinating insects on their farm. The attendees of these sessions now make up a majority of contributors in the NW Pollinators Citizen Science Initiative (CSI) project hosted by our lab. The pollinator guide (as described above) is one of the teaching materials used at these field days and webinars.

Blog/podcast- One of the most impactful outreach projects that has come from this grant is the development of the What’s The Buzz podcast and website. This website is dedicated to research information and blogging from Olsson on status of her projects and general user information. As of September 20, 2017, the website has been visited over 2,500 times by nearly 1,200 unique visitors. The most popular segment of the website is the blog where Olsson posts updates about her research and answers questions from the public. This project allowed Olsson to collect a large series of questions from a general audience that she will continue to use as the platform for helping a general audience understand pollinators, pollination, and garden biodiversity. Questions were asked by a wide and diverse audience, from parents and school teachers to farmers and gardeners, and academics. This blog is ongoing and will continue to disseminate pollinator educational materials to a wide audience. Olsson was also able to produce 4 episodes to date of the What’s The Buzz podcast. In the podcast, Olsson again gives research updates and shares pollinator information, but she also interviews other pollination researchers. This allows the general audience of the podcast to hear from academic scholars in a friendly format that is free and accessible to anyone with an internet connection. www.whatsthebuzzresearch.com