Final report for GW17-019

Project Information

The use of polyethylene mulch in agriculture can lead to environmental problems because of limited disposal options. Biodegradable plastic mulch‒designed to decompose into carbon dioxide (CO2), water, or incorporated into microbial biomass‒could alleviate the disposal problem. The sustainable application of biodegradable plastic mulch will, however, depend on performance, degradability, and effects on agroecosystems. Four biodegradable plastic mulches were tested in hot humid (Knoxville, TN) and cool humid (Mount Vernon, WA) climates in the United States under pie pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo), sweet corn (Zea mays), and green pepper (Capsicum annuum) production. No-mulch, paper mulch, and polyethylene mulch were included as control treatments. The amount of water used for crop production was similar under all mulch treatments. However, the water was efficiently utilized under the biodegradable plastic mulches than the no-mulch and paper mulch, but similar when compared to that in polyethylene mulch. In addition, the biodegradable plastic mulch modulated soil microclimate better than the no-mulch, but not as well as when compared to the microclimate under the polyethylene mulch. The biodegradable plastic mulches affected various soil health indicators (physical, biological, and chemical), with the effect being mostly positive. However, the effects on soil health were not consistent among the mulches, across the two sites, and over the different assessment times. Overall, the biodegradable plastic mulches degraded at a slow rate in soil: 61% to 83% in Knoxville and 26% to 63% in Mount Vernon after 36 months. However, paper mulch which served as a positive control degraded, approximately, 100% within 12 months. Degradability of the biodegradable plastic mulches was also tested in compost, and they underwent 85% to 99% degradation after just 18 weeks. Although the mulches degraded well in compost, micro and nanoparticles were released, which were mostly conglomerate of carbon material. Field days and workshops focused on biodegradable plastic mulch installation, till-down, degradation, and the art and science of composting were organized, and well attended by producers and other relevant stakeholders. In addition, several presentations, publications, extension bulletin, research reports, and other outreach materials were prepared. Through the outreach activities conducted during this project, we were able to reach about 700 different people.

The overall goal of the project is to improve the productivity and environmental sustainability of specialty crop production by evaluating biodegradable plastic mulch as an alternative to polyethylene-based plastic mulch.

Specific objectives:

Objective 1: Evaluate the performance of biodegradable plastic mulches

Objective 2: Determine the effects of biodegradable plastic mulches on agroecosystems

Objective 3: Evaluate the degradation of biodegradable plastic mulches

Objective 4: Engage and educate producers

Cooperators

Research

Objective 1: Evaluate the performance of biodegradable plastic mulches.

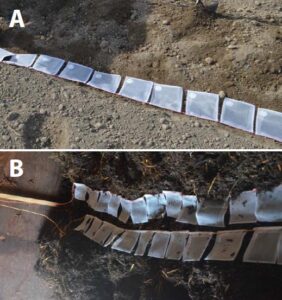

The performance of four biodegradable plastic mulches (BioAgri, Naturecycle, Organix, PLA/PHA), one non-degradable polyethylene mulch, and one cellulosic-paper mulch were evaluated in field experiments at two locations in the United States: (a) hot humid (East Tennessee Research and Education Center, Knoxville, TN) and (b) cool humid (Northwestern Washington Research and Extension Center, Mount Vernon, WA). The mulches were mechanically installed on raised beds of 0.2 m high, 0.8 m wide and 11 m long (Fig. 1). The treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. No-mulch was also included to serve as a control treatment. Pie pumpkin was used in 2016 at both locations, but green pepper at Knoxville, and sweet corn at Mount Vernon in 2017 and 2018. The same plots were used under their respective mulch treatments throughout the study to evaluate the effects of continuous mulch application. In addition, the biodegradable plastic mulch and paper mulch were tilled into the soil after every harvest, but the polyethylene mulch was removed as per intended usage.

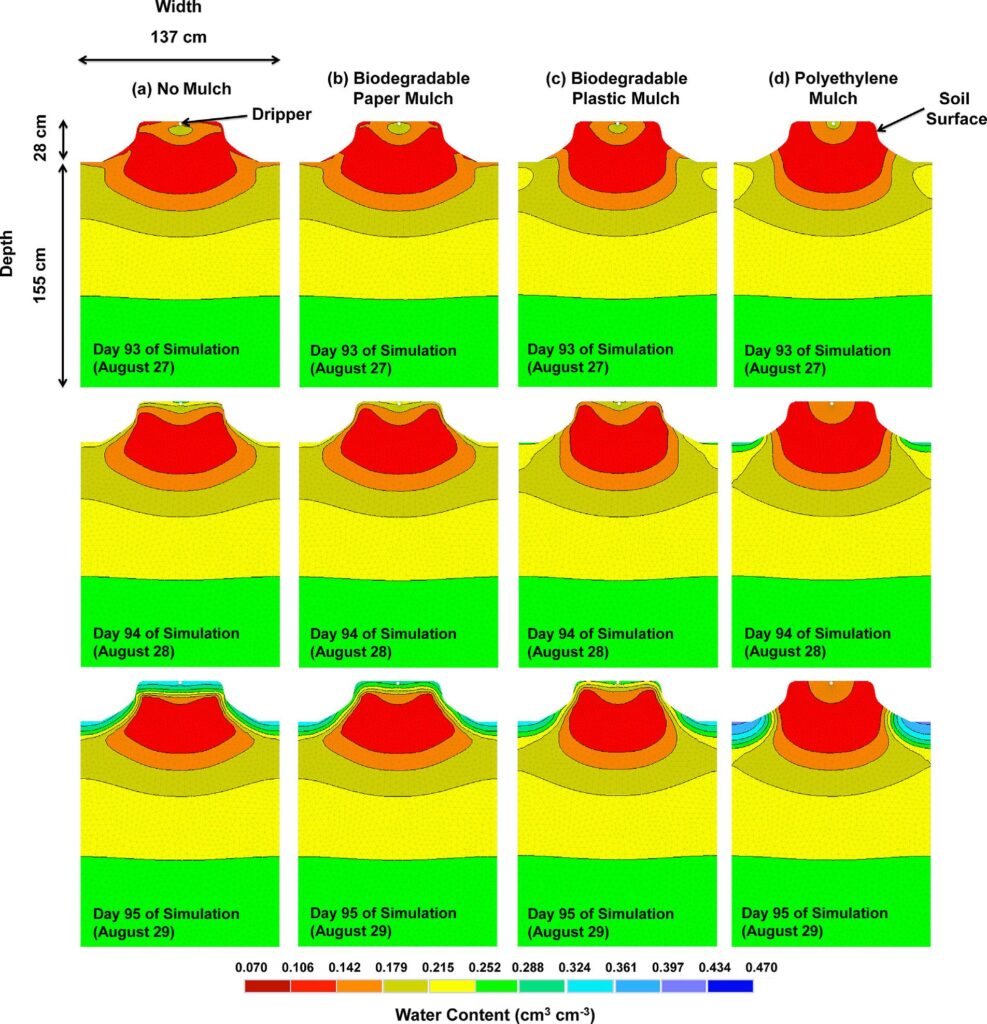

Soil temperature at 10 cm and 20 cm depths were monitored with 5TM sensors, logged with EM50G dataloggers (Decagon Devices Inc, now Meter Group Inc., Pullman, WA). Hourly weather data (precipitation, atmospheric temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity) were collected within each field experiment from adjacent weather stations. In addition, light penetration through mulch was monitored in only Mount Vernon with HOBO Pendant Temperature/Light Data Loggers (Onset Computer Corp., Bourne, MA) placed on the soil surface and directly underneath the mulch treatments. The weather and soil data were used to develop a 2-dimensional Hydrus model to predict soil water flow under the different mulch treatments. The model assumed a no-flux boundary through the biodegradable plastic mulch and polyethylene mulch; however, we noticed that water diffusivity could be high depending on the type of mulch and environmental factors. Thus, a new controlled environment study was conducted to measure water vapor diffusivity through the mulches, which is being used to update the model. In addition, we quantified CO2 flux through holes punched for planting, and the subsequent impact on the growth of sweet corn. The CO2 and water vapor concentrations were measured with a LI-7000 CO2/H2O Analyzer (LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, NE), and a portable infrared CO2 Monitor and Data Logger (CO2 Meter®, Ormond Beach, FL) was used to monitor CO2 concentration at different heights above the soil.

Objective 2: Determine the effects of biodegradable plastic mulches on agroecosystems.

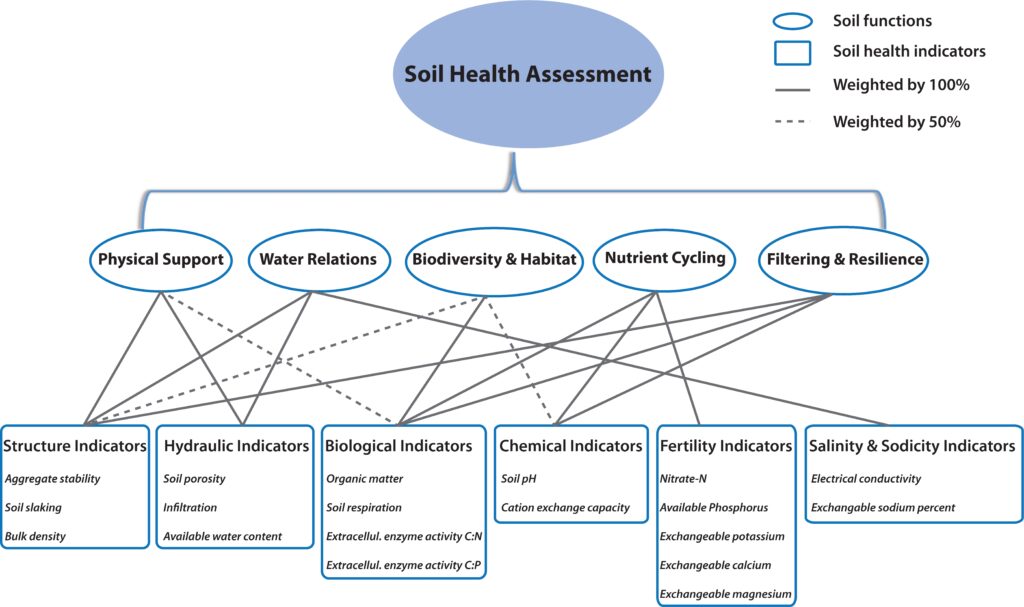

Soil quality assessment was conducted prior to land preparation for planting in the spring and immediately after harvest. Soil parameters included in the assessment are aggregate stability, soil slaking, soil resistance, bulk density, infiltration, soil porosity, available water capacity, organic matter, soil respiration (CO2-C), soil pH, cation exchange capacity, electrical conductivity, exchangeable sodium percent, and essential plant nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium). Soil quality assessment was performed on the same field plots used in Objective 1. Measured soil parameters were converted to index scores and used to derive five soil functions: physical support, water relations, biodiversity & habitat, nutrient cycling, and filtering & resilience. In addition, lysimeters (Drain Gauge G3, Decagon Devices Inc, now Meter Group Inc., Pullman, WA) were installed to collect leachate samples, which were analyzed for organic carbon (dissolved and total), nitrogen (nitrate, nitrite, and total Kjeldahl), phosphorus (orthophosphate and total), electrical conductivity, and pH.

Objective 3: Evaluate the degradation of biodegradable plastic mulches.

Degradation of the mulch treatments was assessed in soil and compost. For soil evaluation, field-weathered mulch samples from the plots after harvest were cut into approximately 10 cm × 12 cm sizes. They were then photographed and placed into 12 cm × 14 cm white nylon-mesh bags with 250 μm openings (Fig. 2). The mesh bags were buried in their respective plots at 10-cm depth and retrieved at 6-month intervals. To evaluate mulch degradation in compost, we collected field-weathered mulch samples and placed them into mesh bags. The mesh bags were then placed at 60-cm depth into a compost pile. The compost was prepared in October as aerated static pile using yard wastes, dairy manure solids, broiler litter, and fish carcasses to obtain C: N ratio of 25-30:1 and 55-65 % moisture content. Temperature was monitored continuously at various locations within the compost pile with TMC50-HD temperature sensor logged with U12-008 data loggers (Onset Computer Corp., Bourne, MA). The mesh bags were retrieved at 2-week intervals for a total of 18 weeks. Mulch degradation was quantified by image analyses used to measure the reduction in surface area of the initial buried mulch samples.

Objective 1: Evaluate the performance of biodegradable plastic mulches

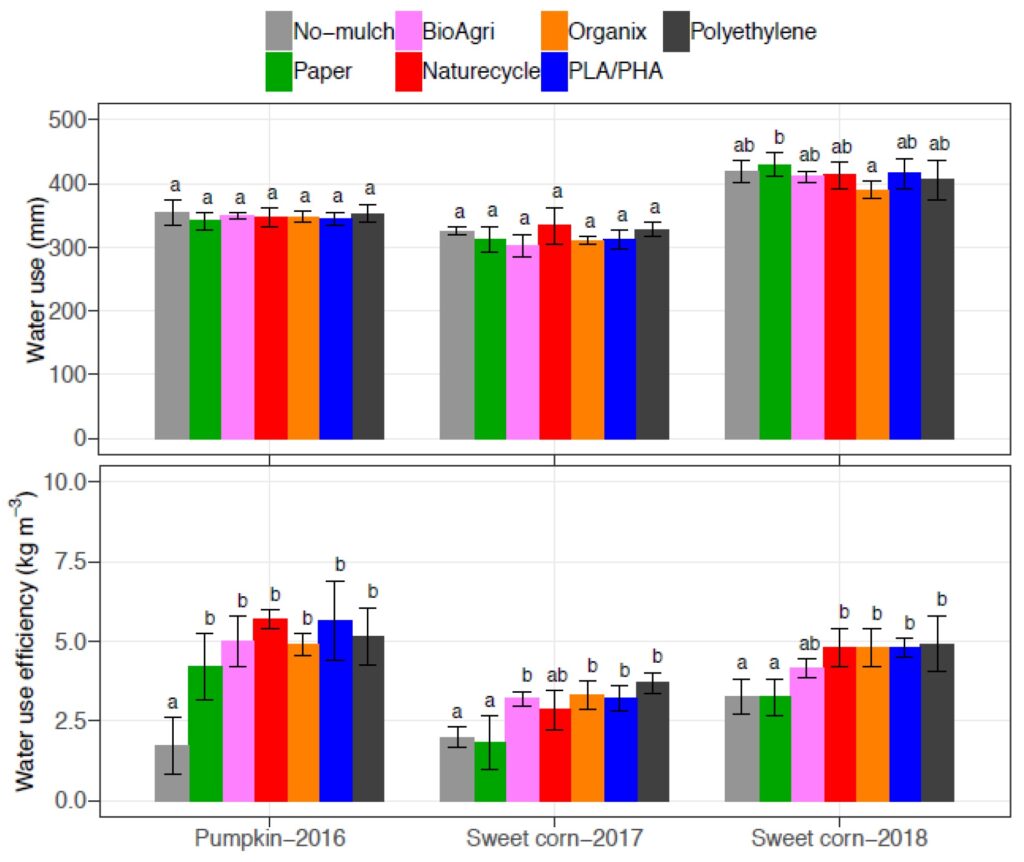

Crop water use under all mulch treatments was equivalent; however, the water use efficiency of the biodegradable plastic mulch was, generally, greater than the no-mulch and paper mulch, but similar when compared to polyethylene mulch (Fig. 3). Averaged water use efficiency of pumpkin and sweet corn under the biodegradable plastic mulch was 79% and 54%, respectively, greater than that under the no-mulch. Based on the water simulation model, polyethylene mulch effectively reduces evaporation but prevents rain to penetrate. The effect causes rain to run off the mulch and infiltrate into the alleyways (Figs. 4 and 5). The biodegradable plastic mulches caused similar effects, but as they disintegrated during the growing season, the case of Naturecycle, they allow rainfall and evaporation to penetrate the soil surface. Paper mulch was partially permeable to rainfall; thus, it allowed evaporation and infiltration of rainwater. Results of the 2-dimensional Hydrus model in predicting soil water flow are published and reported in detailed in Saglam et al. (2017). We note again that the model assumes a no-flux boundary for plastic mulch by creating an impermeable surface layer. However, water loss through plastic mulch may not be negligible depending on the type of mulch and environmental factors.

Table 1 shows water vapor and CO2 diffusion coefficients of the different mulches measured during the controlled environment study in the greenhouse. Water vapor diffusion coefficient of the biodegradable plastic mulch was slightly greater than that of polyethylene, but much lower when compared to the no-mulch and paper mulch. The results suggest that soil evaporation was likely reduced, whereas transpiration was likely increased, under the plastic mulch. Also, the CO2 diffusion coefficient of the biodegradable plastic mulch was slightly greater than that of polyethylene, but much lower when compared to the no-mulch and paper mulch. Overall, the presence of planting holes increased the water vapor and CO2 diffusion coefficients. Thus, CO2 flux from holes punched through the plastic mulch for planting increased correspondingly. The effect subsequently led to elevated CO2 concentration in the air immediately above the soil surface, but the effect was not discernible any longer at 15 cm above the soil surface. Also, the elevated CO2 concentration above the soil surface had no discernible impact on crop growth. These results are being used to develop a crop simulation model under agricultural plastic mulch.

|

Mulch |

Water vapor diffusion coefficients (cm2 s-1) |

CO2 diffusion coefficient (cm2 s-1) |

||

|

No planting hole |

Planting hole |

No planting hole |

Planting hole |

|

|

No-mulch |

8.15×10-2 |

|

1.45×10-2 |

|

|

Paper |

4.39×10-4 |

4.48×10-4 |

1.00×10-4 |

1.34×10-4 |

|

Organix |

40.1×10-7 |

60.1×10-7 |

2.05×10-7 |

9.66×10-7 |

|

Polyethylene |

3.86×10-7 |

30.6×10-7 |

2.60×10-7 |

12.1×10-7 |

Table 1: Water vapor and carbon dioxide (CO2) diffusion coefficients of the different mulches measured under well-watered soil conditions (about 70% of field capacity).

Soil temperature increased by 1 °C to 3 °C under the biodegradable plastic mulch (Table 2). The effect was more pronounced during the early growing season, but the differences diminished as the plant canopy developed. The biodegradable plastic mulch decreased light penetration by two to three orders of magnitude when compared to light illuminance received under the no-mulch. Light penetration was, however, reduced to a greater extent under the polyethylene than under the biodegradable plastic mulches.

|

Mulch |

Average soil temperature (°C) |

|||||||

|

2015 (10 cm) |

2015 (20 cm) |

2016 (10 cm) |

2016 (20 cm) |

2017 (10 cm) |

2017 (20 cm) |

2018 (10 cm) |

2018 (20 cm) |

|

|

One week after planting |

||||||||

|

No-mulch |

18.1 |

17.9 |

20.3 |

19.7 |

18.0 |

17.7 |

17.1 |

17.2 |

|

Paper |

17.9 |

18.1 |

20.1 |

19.3 |

16.8 |

16.9 |

17.7 |

17.6 |

|

BioAgri |

20.2 |

19.7 |

22.6 |

21.4 |

19.5 |

18.9 |

19.3 |

18.9 |

|

Naturecycle |

20.1 |

19.7 |

22.8 |

21.8 |

18.6 |

18.5 |

19.5 |

19.2 |

|

Organix |

19.8 |

19.8 |

22.9 |

22.0 |

19.3 |

19.0 |

19.2 |

18.9 |

|

PLA/PHA |

21.0 |

19.8 |

22.9 |

21.2 |

19.6 |

18.7 |

19.0 |

18.4 |

|

Polyethylene |

21.7 |

21.0 |

22.9 |

22.0 |

18.3 |

18.1 |

19.6 |

19.2 |

|

At harvest |

||||||||

|

No-mulch |

20.3 |

20.3 |

18.8 |

18.8 |

18.8 |

18.9 |

18.1 |

18.3 |

|

Paper |

20.0 |

20.2 |

18.8 |

18.7 |

18.1 |

18.3 |

18.1 |

18.3 |

|

BioAgri |

21.9 |

21.5 |

20.1 |

19.5 |

19.7 |

19.4 |

19.2 |

19.0 |

|

Naturecycle |

21.5 |

21.4 |

20.0 |

19.9 |

19.0 |

19.2 |

19.3 |

19.3 |

|

Organix |

20.9 |

21.2 |

19.1 |

19.3 |

19.5 |

19.6 |

19.1 |

19.2 |

|

PLA/PHA |

21.8 |

21.1 |

19.7 |

19.2 |

19.8 |

19.2 |

19.0 |

18.6 |

|

Polyethylene |

23.3 |

22.7 |

20.1 |

19.9 |

18.8 |

19.1 |

19.7 |

19.5 |

Table 2: Average soil temperature under the different biodegradable plastic mulch after one week of planting and at harvest time in Mount Vernon, WA. Pie pumpkin was planted in 2015 and 2016, and sweet corn in 2017 and 2018.

Objective 2: Determine the effects of biodegradable plastic mulches on agroecosystems

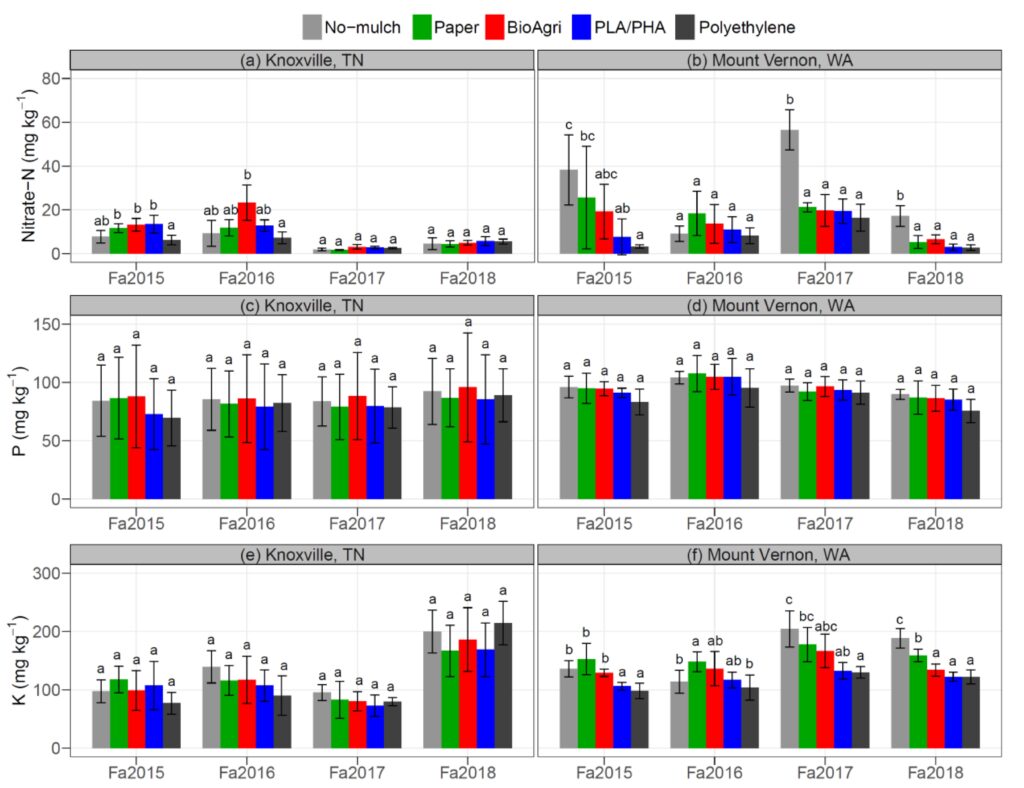

The module used to assess soil health has been shown as a schematic in Fig. 6. In general, the soil properties, soil health indicators, and soil functions were affected more by site and time than by the mulch treatments. However, we did notice significant mulch effects on six soil properties (aggregate stability, infiltration, soil pH, electrical conductivity, nitrate-N, and exchangeable potassium), four soil health indicators (hydraulic, biological, fertility, and salinity & sodicity), and one soil function (nutrient cycling). These effects were, however, not consistent among all the biodegradable plastic mulches, across the two sites, and the sampling times. In general, the biodegradable plastic mulches mostly had a positive impact on soil health where significant effects were observed. For instance, residual soil nutrients after harvest under the biodegradable plastic mulches in Mount Vernon, WA were low, particularly, for nitrate-N (Fig. 7). Thus, nutrient loads in leachate samples were correspondingly low, which has implications on water quality.

Objective 3: Evaluate the degradation of biodegradable plastic mulches

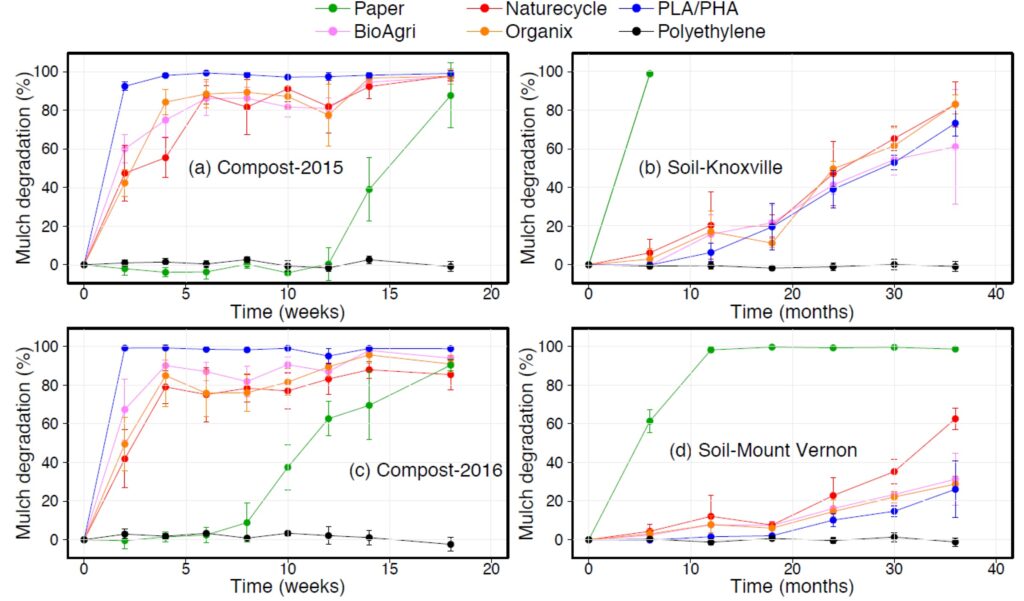

The biodegradable plastic mulches degraded at a faster rate in compost than in soil, and at a faster rate in soil at Knoxville, TN than in Mount Vernon, WA (Fig. 8). Degradation ranged from 85% to 99% after 18 weeks in compost; 61% to 83% after 36 months in soil at Knoxville, TN; and 26% to 63% after 36 months in soil at Mount Vernon, WA. Paper mulch degraded well in both compost and soil, and polyethylene did not degrade in either system. The results suggest the importance of environmental variables in mulch degradation, with the impact of temperature being the most prominent. Also, the physicochemical properties of the biodegradable plastic mulches played a critical role, as shown by the differences in the degradation rates of the mulches. Overall, PLA/PHA degraded at a faster rate in compost, whereas Naturecycle degraded at a faster rate in soil at both sites.

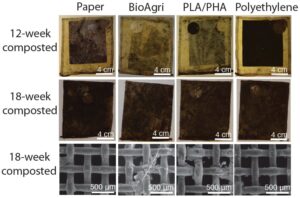

Despite the greater extent of degradation of the biodegradable plastic mulches in compost, residues that stained the mesh bags were observed (Fig. 9). The number of residues observed on the mesh bags that contained the biodegradable plastic mulches was much higher than those found on the mesh bags that contained paper mulch and polyethylene. We, therefore, think that some of the residues stemmed from the biodegradable plastic mulches. Further analyses showed that the stains on the mesh bags contained micro- and nanometer-sized particles, that were mostly conglomerate of carbon material. We therefore think that the residues likely contained carbon black, which is a common additive used to render black color in plastics, and they are fossil-fuel-derived.

Research Outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation Summary:

Presentations: Oral and poster presentations on findings of the project were made at 2016, 2017, and 2018 ASA-CSSA-SSSA annual meetings, and the Crop and Soil Science Department seminar session in 2017 and 2018. The presentations were mainly attended by scientist and students, and a few producers attended as well. We also gave presentations during the various field days and demonstration field plot tours. We received several questions during our presentations, demonstrating that people had a keen interest in the findings of the project.

Publications:

Journal Publications

Sintim, H.Y., Bary, A.I., Hayes, D.G., English, M.E., Schaeffer, S.M., Miles, C.A., Zelenyuk, A., Suski, K., Flury, M. Release of carbon black micro- and nanoparticles from biodegradable plastic mulch during in situ composting. Sci. Total Environ. (submitted, and revision has been requested).

Sintim, H.Y., Bandopadhyay, S., English, M.E., Bary, A.I., DeBruyn, J.M., Schaeffer, S.M., Miles, C.A., Reganold, J.P., Flury, M. 2019. Impacts of biodegradable plastic mulches on soil health. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 273, 36–49.

Saglam, M., Sintim, H.Y., Bary, A.I., Miles, C.A., Ghimire, S., Inglis, D.A., Flury, M., 2017. Modeling the effect of biodegradable paper and plastic mulch on soil moisture dynamics. Agric. Water Manag. 193, 240–250.

Sintim, H.Y., Flury, M., 2017. Is biodegradable plastic mulch the solution to agriculture’s plastic problem? Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 1068–1069.

Extension Publications:

Sintim, H.Y., Shahzad, K., Bary, A. I., and Flury, M. 2017. Navigating WSU Puyallup compost mixture calculator. Puyallup Research and Extension Center, WSU, Puyallup, WA.

Sintim, H.Y., Shahzad, K., Bary, A. I., and Flury, M. 2017. How well does biodegradable plastic mulch degrade in compost and soil? Puyallup Research and Extension Center, WSU, Puyallup, WA.

Flury, M., Bary, A., DeBruyn, J. Schaeffer, S., Sintim, H., and Bandopadhyay, S. 2015. What is soil quality and how is it measured? Report # SE-2015-01, Biodegradable Mulch, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Outreach: We collaborated with the technology adoption group of the larger project and organized field days at Cloudview Farm, Ephrata, WA. The field day focused on how to lay and till down biodegradable plastic mulch effectively. In addition, we collaborated with the Pierce County Conservation District and organized a workshop on composting at the Puyallup Research and Extension Center of Washington State University. We coordinated a research field plot tour for the Board Members of Washington Recycling Organic Council. The Board Members work for various departments and agencies, such as the USDA National Organic Program, the US Environmental Protection Agency, US Department of Ecology, and Commercial Compost Facility Operators, which are important stakeholders of the project. We granted an interview to Dr. Colin Campbell of Meter Group, Inc., who used the information we shared with him to write newsletter articles about our project. Our project was also featured in the “Fresh from the Field” bulletin of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

By the help of Washington State University extension scientists, a pool of producers was identified, and they were engaged throughout the entire duration of the project. We continue to follow up with producers and stakeholders to determine the impact of our project on their knowledge and activities. Through our outreach efforts, were able to reach about 700 different people.

Featured News/Articles:

USDA-NIFA, 2018. Biodegradable plastic mulch. USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. https://nifa.usda.gov/announcement/biogradable-plastic-mulch

Campbell, C. 2016. Are biodegradable mulches actually better for the environment? (Part II). Environmental Biophysics. http://www.environmentalbiophysics.org/biodegradable-mulches-actually-better-environment-part-ii/

Campbell, C. 2016. Are biodegradable mulches actually better for the environment? Environmental Biophysics. http://www.environmentalbiophysics.org/biodegradable-mulches-actually-better-environment/