Final report for GW21-224

Project Information

As farmers confront the fragility of California’s water system, a crucial question emerges: how can farmers adapt to water scarcity without jeopardizing their livelihoods? Innovative farmers have turned to dry farming, a method of growing produce with little to no external water inputs, and a radical departure from irrigated agriculture. Conversations with six such farmers in the Central Coast region reveal strong interest in research that evaluates the soil microbial and nutrient factors that can best support dry farm crops.

We propose to assess how farmers can shape soil microbial communities through fungal inoculants and nutrient management in ways that enhance dry farm tomatoes’ performance. Recent trials have established fungal inoculants as tools to alleviate crop water stress, making them ideal candidates for dry farm soils; however, high soil nutrient concentrations deter plant-fungal symbioses. Through participatory research we will measure soil nutrients and plant-fungi symbioses to determine whether inoculation can profitably improve fruit yields and quality, and under what soil nutrient conditions.

We will also help facilitate a dry farming community of practice by collaborating with participating producers and local ag advisors to organize a producer workshop, encouraging attendance among experienced and potential new dry farmers in addition to local land and groundwater policy stakeholders. Our findings will be shared through presentations at conferences, and in videos, factsheets, op-eds, and a peer-reviewed publication. Through increased awareness and improved techniques, we hope to grow the practice of dry farming, preserving water as we build the dry farm community.

- Coordinate field trials through on-farm participatory research to engage farmers in research design and outcomes. In Spring 2021 we began on-farm trials on seven dry farm tomato fields after having engaged in a participatory design process with dry farmers on California’s Central Coast. These farmers have a shared interest in identifying management practices that can limit blossom-end rot and increase yields, leading us to focus our study on how to manage dry farm soils to encourage fungal symbionts that show potential to improve both fruit yields and quality. The project allowed us to collect labor-intensive harvest data from the indeterminate tomato varieties grown on the fields, and to analyze soil/root samples to provide farmers with information on how to best manage dry farm soils to support beneficial fungal communities.

- Characterize fungal communities and quantify the utility of fungal inoculants. Our project builds on promising preliminary trial results with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. We set up five inoculated and five non-inoculated plots in each field to determine which native fungal species are present and deepen our understanding of the relationship between fungal diversity and improved farm production, while testing whether fungal inoculation has the potential to improve tomato performance on dry farms.

- Identify soil management strategies that enhance fruit yield and quality, and evaluate their profitability. Because high nutrient concentrations can limit plant-fungi associations, we tracked soil nutrient levels (nitrogen and phosphorus, both available and total) to pair with fungal and harvest data. Of particular interest is nutrient depth, as some farmers go to great lengths to deliver nutrients deeper into the soil profile in dry farm systems. Also of interest is field history—i.e., number of years since most recent irrigation—as previously dry soils may prime native beneficial microbial communities. We will identify the soil management strategies (inoculation, nutrient depth, etc.) that show the strongest yield/quality improvements, and compare farm revenue generated by each practice to expected management costs to determine profitability.

- Engage Central Coast farmers and stakeholders in collaborative learning about dry farm soil management. We maintained a blog over the course of the field trials to build connections between participants and maintain engagement in the research process. In the second year of the project, after data have been analyzed, our producer workshop will allow farmers to connect with research results, one another, and relevant land and water stakeholders.

- Disseminate findings to build the dry farm community and public engagement. A video we produce, two conferences, a factsheet, and the producer workshop will help us communicate our results to producers, improving dry farm soil management, lowering barriers to beginning dry farmers, and introducing new farmers to the practice. A policy memo and a publication for a general audience will increase public interest in dry farming, as well as potentially shaping policy to incentivize the practice.

In September and October 2021 I will complete field trial harvests. I will then process and analyze soil, root, and fruit samples from October through Spring 2022. After samples are processed, I will analyze data to round out the first year of the project. As I obtain results from data, I will work to create the inoculation factsheet and draft the soil management video.

In the second project year, I will develop and host the producer workshop in Fall 2022/Winter 2023 and will follow up with attitude and adoption surveys that same winter. During this time I will also work on the peer-reviewed publication and middle school classroom presentation. Following the workshop, I will present at the EcoFarm Conference and CalCAN summit. I will finish the project in Spring/Summer 2023 by filming and editing the dry farm soil management video and will work on authoring general-audience publications in the 2023-2024 academic year. Full timeline details in Table 1.

Table 1. Timeline.

| Activity | Academic Year | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | ||||||

| Fall, Winter, Spring, Summer | F | W | Sp | Su | F | W | Sp | Su | |

| Objective 1: Participatory field trials | |||||||||

| Complete on-farm field trials | x | ||||||||

| Objective 2: Characterize fungal communities and quantify inoculation benefits | |||||||||

| Harvest tomatoes and assess quality | x | ||||||||

| Process and analyze root samples | x | x | x | ||||||

| Objective 3: Identify best practices for soil management | |||||||||

| Collect and process soil samples | x | ||||||||

| Soil nutrient analyses | x | x | x | ||||||

| Data analysis | x | ||||||||

| Objective 4: Engage farmers and stakeholders in collaborative learning | |||||||||

| Maintain weekly blog | x | ||||||||

| Workshop and survey development | x | x | |||||||

| Send workshop invitations | x | ||||||||

| Workshop day | x | ||||||||

| Send post-workshop survey | x | ||||||||

| Objective 5: Disseminate findings to dry farm community and public | |||||||||

| Prepare and disseminate factsheet | x | x | |||||||

| Prepare, film, and edit video | x | x | x | ||||||

| Prepare scholarly peer-reviewed article | x | x | x | ||||||

| Give classroom presentation | x | ||||||||

| Present at EcoFarm and CalCAN | x | x | |||||||

| Compose policy memo and general-audience piece | x | ||||||||

In addition to this initial timeline, we will continue working on two scholarly peer-reviewed articles, a policy memo and a general-audience piece in the 2023-2024 academic year.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Technical Advisor - Producer (Educator)

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

All field and lab work will be carried out in accordance with UC Berkeley COVID protocols.

Objective 1: Coordinate field trials through on-farm participatory research to engage farmers in research design and outcomes

In Fall 2020-Spring 2021, I interviewed eleven Central Coast farmers to better understand dry farming and identify research priorities for farms in the area. All farmers either identified fungal inoculants as an area of keen interest or were excited when I suggested it as a research option, yet none had previously experimented with applying fungal inoculants on their operations. Farmers were additionally curious about broader questions of what soil health means in the context of dry farming, where field outcomes often shirk conventional wisdom about best practices. Of the eleven, eight farmers (representing six farms) had operations large enough to accommodate field trials, and all were enthusiastic to join the project.

During field visits to each farm, I collaborated with growers to develop a research plan that fits the system and addresses conditions and questions relevant to each participating farm. We decided that each farm could feasibly host ten 12-plant plots, which I then manipulated and sampled from (growers had no change to their management of these plots compared to the rest of the field). After my initial intervention to inoculate half of the plots, I sampled soils (see Objective 2) and collected yield data to give farmers desired information on the potential benefits of fungal inoculation and other soil management techniques (see Objective 3).

Funding from Western SARE has allowed me to collect the full set of data that farmers have identified as being of particular interest: soil nutrients, inoculant efficacy, field fungal communities, yields, and fruit quality (see Objective 2). I continued communicating closely with farmers over the course of the growing season and after sampling was complete to ensure that their observations about the plots are included in data interpretation and further refinement of research questions. I also shared preliminary data and results with farmers, which was well-received; all farmers indicated that they would use the information provided in subsequent management decisions.

Project Team Members: Myself (YS); Advisor Tim Bowles (TB); Ag Advisor Jim Leap (JL); Producers Joel Schirmer, Thomas Broz, James Cook, Larry Palla, Barbara Palla, Verónica Mazariegos-Anastassiou, and Darryl Wong.

Project Team Roles:

- Identify research questions of interest: YS, JL, Producers

- Preliminary experimental design: YS, TB

- Iterative experimental refining: YS, TB, Producers

Objective 2: Characterize fungal communities and quantify the utility of fungal inoculants

Soil management shapes fungal communities, which in turn impact agricultural yields and crop quality. Practices such as cover cropping, crop rotation, and fertilization contribute to mycorrhizal fungal diversity, and the resulting communities vary in hyphal growth rate, turnover rate, spore production, and more. Interactions between these traits, host plants, and the abiotic environment influence how “helpful” a mycorrhizal community will be, with more diverse communities showing the best yield outcomes. In addition, a history of dry soils (i.e., lack of irrigation) in a field may prime native beneficial microbial communities. Farmers are therefore interested in understanding which management practices (inoculation, rotational history, fertilization, etc.) will produce diverse fungal communities that are best suited to the crops growing in their fields. Our research explores these questions on seven dry farm fields on California’s Central Coast. These fields grow Early Girl, New Girl, and Dirty Girl tomatoes and belong to six producer collaborators (one farm is contributing two fields).

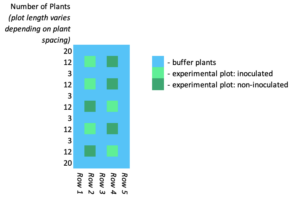

I used a nested experimental design to account for management and biophysical differences across fields, establishing 10 plots at each field site (70 plots total). Experimental plots (12 plants each) were distributed across two adjacent rows with or without a buffer row between them, depending on the size of the field (Figure 1). Each experimental row began and ended with at least ten buffer plants, and there were three buffer plants between experimental plots. Each experimental plot ranged from 13-44 ft in length depending on the spacing between each plant, but always contained 12 plants at transplant. Buffers between plots were similarly variable in length (3-8 ft), and always contained 3 plants at transplant. Inoculation was distributed in a randomized complete block design to account for heterogeneity in biophysical environments across the field. To accomplish this, each of the plots in rows 2 and 4 was paired with its closest counterpart in the opposite row (forming a block), and inoculant was randomly applied to one of the plots in each pair within three days of when farmers transplanted their first dry farm tomatoes (April-May).

I inoculated with Valent’s MycoApply Ultrafine Endo, a mix of four species of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: Glomus intraradices, Glomus mosseae, Glomus aggregatum, and Glomus etunicatum. These species are known for having an aggressive growth strategy, which can benefit crops by establishing quickly but may also disrupt already high-functioning native communities. This inoculum is one of several commercially available mycorrhizal inoculants and was shown to decrease water stress in preliminary field trials with processing tomatoes in Summer 2020.

I inoculated experimental plants by mixing the inoculum with water to create a slurry that can be poured at the base of each plant. Valent confirmed that this is an effective inoculation technique, though several others can be used for ease of application (e.g., drenching root balls in a water-inoculum mixture before transplanting).

Mid-way through the season, I sampled one plant per plot to collect roots, which were split into two sample sets: one for fungal colonization quantification, and one for DNA analysis to determine which fungal species are colonizing the roots. Roots for colonization were stained and dyed, and fungal presence is being quantified via microscopy. Roots for DNA analysis were ground and extracted with a kit, and DNA was quantified. These samples were sent to the University of Minnesota's Genomic Center for Illumina MiSeq sequencing using ITS2 primers. Fungal community data were used to determine whether the inoculated species are in fact colonizing plant roots, and for further explorations of soil health (see Objective 3).

I used Bayesian generalized mixed effect models to explore the relationship between yields/fruit quality and inoculation, fungal species diversity (Shannon index), and soil nutrients/water at varying depths, with random effects of field, block, and plot to account for management differences and spatial heterogeneity. See Objective 3 for further fungal analysis.

Project Team Members: Myself (YS), Producers, two Undergraduate Assistants (UA)

Project Team Roles:

- Plot setup: YS, Producers

- Sample collection: YS

- Root analyses (colonization and DNA): YS, UA

- Communication of results: YS, Producers

Objective 3: Identify soil management strategies that enhance fruit yield and quality and evaluate their profitability

Though irrigated tomato plants usually cluster their roots at the surface of the soil (close to the water source), dry farm tomatoes send their roots into deeper soils to scavenge for water and nutrients (40). It was therefore important to collect data about nutrients across the soil profile to determine which nutrient depths are most influential for dry farm tomatoes. Because high levels of phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N) can also inhibit plant-fungus associations, it is be important to consider both the minimum and maximum nutrient thresholds for optimal dry farming performance.

Soil samples were taken at three points over the course of the field season: once at transplant (within two weeks of plant date), once mid-season (9 weeks after transplant), and once during harvest (18 weeks after transplant). I sampled at four depths (0-15cm, 15-30cm, 30-60cm, 60-100cm) at all soil sampling events. In the lab, samples were stabilized (air dried or KCl extractions) and stored for further analysis.

WSARE funds allowed me to test soil samples for available N (nitrate and ammonium) and available P (Olsen P) via colorimetry. I also measured gravimetric water content from each soil sample to track water availability in each plot throughout the top meter of the soil profile.

When fruits began to mature, I coordinated with farmers to harvest and weigh the tomatoes from each plot once per week. Funds from WSARE allowed me to hire two undergraduate students to assist with the harvest, making it possible to conduct weekly harvests for the ~10 weeks of production on each field. Tomatoes from each plot were sorted into marketable, blossom-end rot, and sunburnt fruit, and then weighed. I also collected marketable fruit samples from each plot at harvests 3, 6, and 9 to test for tomato quality via fruit water content.

I used Bayesian generalized mixed effect models to explore relationships between each response variable (total marketable fruit, fruit lost to blossom-end rot, fruit water content) and inoculation, soil nutrients (N, P, and N:P ratio at each sampling depth), soil water content, field legacy (years since last irrigation), and fungal species diversity (from Objective 2). Random effects of field, block and plot accounted for unmeasured attributes such as climate, management differences, and spatial heterogeneity in field soils. I treated marketable and blossom-end rot fruit as repeated measures due to the 10+ consecutive weeks of sampling.

To better understand the economic structures and profitability behind dry farming, I also conducted semi-structured interviews with the same farmers who participated in the field study.

Project Team Members: Myself (YS), Advisor Tim Bowles (TB), Producers, two Undergraduate Assistants (UA)

Project Team Roles:

- Sample collection: YS, UA (at harvest)

- Fruit harvest: YS, UA

- Soil lab analyses (N, P, gravimetric water content, DNA extraction): YS, UA

- Data analysis: YS, TB

- Communication of results: YS, Producers

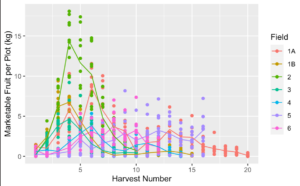

Fruit harvests lasted 10-20 weeks and tended to peak 3-5 weeks after the first harvest (Figure 1). These peaks coincided with when fruit quality was at its highest, as measured by fruit percent dry mass (optimal range is 8-12% dry mass by weight; Figure 2). Because there are very few conventionally farmed tomatoes in the Central Coast region due to its cool, moist climate, it is difficult to compare these numbers to what might be found in a conventional system. The cumulative marketable harvest for an individual field ranged from 175 - 542 kg per field, or 1.5 - 4.5 kg per plant, with an average of 315 kg per field and 2.6 kg per plant. Over the course of the season, on average 4.7% (sd = 11%) of the fruits harvested from each experimental plot were unmarketable due to blossom end rot.

Figure 1. Marketable fruit yield per experimental plot in weekly harvests.

Figure 2. Tomato fruit quality in each experimental plot as measured by percent fruit dry matter (by weight).

Due to the large number of potential covariates (nutrients and water at four depths for each of three sampling events), soil variables were grouped and summarized by their principal components. The groupings were nutrients at 0-15cm, 15-30cm, 30-60cm, 60-100cm, water, and texture. The variables within each group are listed in Table 1. Enough principal components were included to account for at least 70% of the variance in the data.

|

Group |

Variables |

Number PCs retained |

|

Nutrients, 0-15cm |

Nitrate, Transplant Nitrate, Midseason Nitrate, Harvest Ammonium, Transplant Ammonium, Midseason Ammonium, Harvest Phosphate, Transplant Phosphate, Midseason N:P, Transplant N:P, Midseason |

3 |

|

Nutrients, 15-30cm |

Nitrate, Transplant Ammonium, Transplant Phosphate, Transplant N:P, Transplant |

2 |

|

Nutrients, 30-60cm |

Nitrate, Transplant Nitrate, Midseason Nitrate, Harvest Ammonium, Transplant Ammonium, Midseason Ammonium, Harvest Phosphate, Transplant Phosphate, Midseason N:P, Transplant N:P, Midseason |

3 |

|

Nutrients, 60-100cm |

Nitrate, Transplant Ammonium, Transplant Phosphate, Transplant N:P, Transplant |

2 |

|

Water |

GWC, 0-15cm, Transplant GWC, 0-15cm, Midseason GWC, 0-15cm, Harvest GWC, 15-30cm, Transplant GWC, 15-30cm, Midseason GWC, 15-30cm, Harvest GWC, 30-60cm, Transplant GWC, 30-60cm, Midseason GWC, 30-60cm, Harvest GWC, 60-100cm, Transplant GWC, 60-100cm, Midseason GWC, 60-100cm, Harvest |

1 |

|

Texture |

Percent Clay, 0-15cm Percent Clay, 15-30cm Percent Clay, 30-60cm Percent Clay, 60-100cm Percent Sand, 0-15cm Percent Sand, 15-30cm Percent Sand, 30-60cm Percent Sand, 60-100cm |

1 |

Table 1. Soil data collected and principal components included in linear mixed models.

We found that plants only access nutrients below 30cm (where ammonium decreased the incidence of blossom end rot), and more often 60cm (where ammonium increased fruit quality and lowered yields, while nitrate increased yield). These results highlight two core challenges for dry farmers. First, there is a tension between fruit quality and yields, with conditions that lead to high yields decreasing fruit quality and vice versa. Second, it is difficult to manage soil fertility deep in the soil profile, and farmers may have to plan a year or more in advance to have an impact on nutrient levels at depth.

We also found that commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculants are ineffective on these farms (as opposed to resident AMF communities, which are fostered through diversified management and typically improve harvest outcomes). We were able to provide farmers with immediately actionable information about how dry farm systems function and their management implications (avoid AMF inoculants, focus on fertility changes below 60cm).

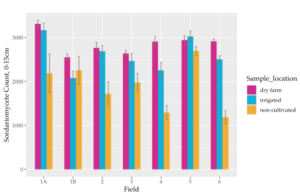

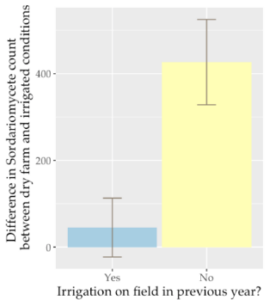

Dry farm soils were consistently enriched in taxa in the class Sordariomycetes (see Figure 3). These indicator taxa formed a dry farm “signature” that was not only present in dry farm soils, but increased in magnitude in soils that had gone multiple years without external water inputs (Figure 4). This signature (i.e. Sordariomycetes counts) showed positive associations with fruit quality outcomes, which is of particular importance to farmers in this quality-driven system. We therefore encourage farmers to experiment with rotations that include only dry farm crops (e.g. winter squash, dry beans, potatoes) and even consider setting aside a field to be dry farmed in perpetuity.

After conducting interviews, I emerged with a synthesis of farmer-stated environmental constraints that I used to create a map of California cropland that could be suitable for future dry farm production. As I considered an expansion of dry farming onto these new lands, I drew on farmers’ experience to explore how to maintain dry farming’s history as an agroecological alternative to the industrial style of farming that dominates the region. Farmers had a clear message about the small operations and direct-to-consumer marketing styles that have been the foundation of dry farming success, and that serve alongside soil health practices as a model for an agroecological transition towards water savings in California. I identified policies such as publicly funded demonstration farms, participatory breeding programs, and public procurement that could promote dry farm expansion while preserving its fuller context and identity, rather than stoking a shift toward an industrial cooptation of the practice that could edge small growers out of dry farm markets.

Research outcomes

Our research suggests three main management outcomes for dry farmers and those severely restricting irrigation inputs on fields.

- Only fertility at depth will impact harvest outcomes. Consider exploring diversified management practices (cover cropping, composting, etc.) to build fertility below 60cm.

- Commercial AMF inoculation is not effective in these diversified systems, even though plants are under water stress.

- Consider using dry farm rotations that allow soils to remain irrigation-free or multiple years in a row.

Together, these findings begin to shed light on research directions that could most directly benefit dry farming and the farmers that practice it. Funding for both farmers and researchers to explore varieties and breeding programs through community based participatory research would allow crops beyond tomatoes to be incorporated into dry farm rotations. Given that fungal communities adapt to non-irrigated management increase fruit quality, farm profits and agricultural water saving will both benefit from the development of dry farm crop rotations.

We further identify areas in California that are likely good targets for future dry farm vegetable management. We recommend that outreach be done to provide educational tools to farmers in regions that have not historically practiced or been exposed to vegetable dry farming. We also recommend that trials be conducted to experimentally determine the climatic and edaphic limits on where dry farming can be successful in the state, as well as crops and varieties that are best suited to the practice.

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

The main outreach events were:

- Direct outreach to farmers participating in the study to outline results from their fields (2021 - 2023)

- A session at the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF) small farms conference (2022, 2023, 2024)

- A presentation at the Lunchtime Organic Agriculture Seminar Series for Growers (hosted by UC Cooperative Extension) (2022)

- A farm demonstration and learning circle in partnership with American Farmland Trust (AFT). (2022)

- Dry farming collaborative winter convening (2023)

- Dry farm symposium (2023)

- Presentations to lab groups at OSU and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

- Dry Farming Strategies Workshop hosted by UCANR (2024)

- A talk at the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF) summer soiree (2024)

For the direct outreach to farmers participating in the study outlining results from their fields (7 farmers total), I prepared two packets for each farm (one shared in 2022, the other in 2023). The first showed soil and harvest data that we collected from their field, while the second contained information on fungal communities. Each time I spent ~1 hour on each farm discussing fungal results, nutrient management, and yield outcomes, and answering questions the farmers had about the study.

For the sessions at the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF) small farms conference I gave two virtual presentation. The first was titled "Managing mycorrhizas on your farm" along with three coauthors to an audience of 80 farmers and agricultural professionals. The second was titled "Dry Farming Practices and Perspectives" and facilitated a conversation with 6 dry farmers for an audience of 125. The third was titled "In deep water:Management learnings from diversified dry farm tomato systems" as an invited panelist for an audience of 90.

For the presentation at the Lunchtime Organic Agriculture Seminar Series for Growers I gave a virtual presentation titled "Managing mycorrhizas on your farm" along with three coauthors to an audience of 54 farmers and agricultural professionals.

For the farm demonstration and learning circle, I partnered with Caitlin Joseph at the American Farmland Trust to host an event titled "Dry Farming Techniques for Small Farm Resilience in California: A Women for the Land Learning Circle" at Brisa Ranch, one of the farms participating in the study. At the event, we discussed dry farming, did demonstrations on the farm, and invited technical assistance providers to share resources. Nine farmers and 12 agricultural professionals were in attendance.

At the dry farming collaborative winter convening, I gave a talk titled "Going beyond surface level: How nutrient depth impacts fruit yield and quality in dry farmed tomato systems" to 145 farmers, researchers, and agriculture professionals.

I organized the Dry Farm Symposium, which was a day spent talking with 50 farmers, researchers, and policymakers about the current state of dry farming and the policies that influence it. Though survey response rates were too low to collect meaningful quantitative data, many participants were vocal in expressing their appreciation for the event.

For the Dry Farming Strategies Workshop hosted by UCANR, I gave a talk about research findings to 20 farmers in the North Bay area.

For the talk at the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF) summer soiree, I gave a talk about vegetable dry farming and the need for research in agricultural water resilience to 150 attendees.

Two outreach videos were published in fall 2023 detailing the research process an findings and were featured in various social media outlets. The videos have at least 231 unique views.

We have found in-person communication to be most effective in achieving our education and outreach goals. Though zoom events have helped gain a wider audience, nothing compares to in person conversations for facilitating collecting and disseminating research results. One-on-one conversations with participating farmers allowed us to both share and better interpret our results while maintaining relationships with farmers. Gathering many farmers and agricultural professionals together for the dry farm symposium was particularly successful in building a dry farming community and garnering excitement for the management system and people who practice it. Though pre- and post-survey response rates were too low to collect meaningful quantitative data, many participants were vocal in expressing their appreciation for the event, especially as a space to connect with other dry farmers.