Final report for LNC14-358

Project Information

Organic farmers in the North Central Region face a regional shortage of organically produced seed potatoes, limited availability of desired specialty varieties, and limited information on variety performance under organic management. Very little potato breeding and selection focuses on the needs of organic farmers. A decentralized system of seed potato production and breeding by a network of organic farmers would meet regional seed potato demands, enable farmers to evaluate and select outstanding lines from crosses between existing varieties, and promote interaction and learning among farmer peers. This project brings together researchers and farmers to develop goals for breeding and seed production, to trial seed potato production and breeding on organic farms, and to assess economic impacts of on-farm seed potato production.

Objective 1: Evaluate the practical and economic feasibility of on-farm production of high quality seed potatoes from minitubers and foundation class seed potatoes.

Since many pathogens of potatoes can be transmitted in tubers and will impact the productivity of the next crop, commercial seed potato production involves production and testing protocols aimed at limiting the incidence of pathogens in potato crops sold as seed potatoes. The process begins with plants propagated in sterile tissue culture, which are then grown in protected greenhouse environments to produce disease free “minitubers”. These minitubers are used for field production of foundation and certified seed potatoes. By Wisconsin law, foundation seed potatoes must meet a threshold of less than 0.5% virus incidence, and are the lowest allowable class for replanting by seed potato growers. Certified seed potatoes must meet a threshold of less than 5% virus incidence. Both grades have zero tolerance for bacterial ring rot and potato spindle tuber viroid. Other seed potato producing states have similar standards.

Changes to Wisconsin seed potato law passed in August 2017 (Wisconsin Senate Bill 23) require all farmers who plant more than 5 acres of potatoes to use only certified seed potatoes inspected by the Wisconsin Seed Potato Certification Program, or by an equivalent program in another state. In the Upper Midwest, only two organic farms produce certified seed potatoes – Vermont Valley Community Farm (WI) and since 2016, Carter Farms (ND). Since organic growers are required to source organically produced seed potatoes if possible, the limited supply of organically produced certified seed potatoes in the Upper Midwest is a problem for Wisconsin growers who plant more than 5 acres of potatoes.

Most commercial seed potato growers plant foundation seed potatoes rather than minitubers, but since organic growers require a wider variety and smaller scale of production, it is less economically feasible to produce foundation seed potatoes. Minituber production in greenhouse conditions is more scaleable, and could provide planting stock for an organic seed potato system. For this objective, participating organic growers trialed on-farm production of seed potatoes from minitubers or foundation seed potatoes in field, hoophouse and greenhouse conditions.

Objective 2: Provide training, coordination and resources for a farmer-participatory potato breeding network.

Farmers were provided with progeny from crosses between varieties that performed well on organic farms in our previous trials. Progeny were provided as true potato seed and also as tubers derived from crosses. Several participants enthusiastically participated in growing potatoes from true seed, while others found it more time-efficient to plant tubers derived from F1 crosses. To supply these tubers, we planted either transplants or minitubers from F1 seed in organic plots at West Madison Agricultural Research Station and selected tubers to share with participants. Participants were provided with guidance on starting seedlings from true potato seed, on plot design, on evaluation in-season and at harvest, and on storage of tubers for replanting.

Cooperators

Research

Objective 1: Evaluate the practical and economic feasibility of on-farm production of high quality seed potatoes from minitubers and foundation class seed potatoes. Due to changes to Wisconsin seed potato law which require use of certified seed potatoes by farms that plant more than 5 acres of potatoes, this objective was modified to focus on the feasibility of on-farm production of certified seed potatoes. The pathogen Potato Virus Y (PVY) is the most limiting factor in Midwest production of certified seed potatoes. We hypothesize that incidence of PVY in tubers harvested from plots planted with foundation seed potatoes (less than 0.5% PVY) will vary with farm location and proximity to major potato production regions. We will use price data from organic certified seed potato producers to assess the economic feasibility of on-farm organic seed potato production.

Objective 2: Provide training, coordination and resources for a farmer-participatory potato breeding network. We hypothesize that using potato varieties that have previously performed well in on-farm organic variety trials as parental lines will result in a high frequency of progeny lines adapted to organic growing conditions. As potatoes are highly heterozygous tetraploids, progeny are highly variable. During the selection process, only 1 in 100 progeny may be sufficiently outstanding to be selected for replanting, with even fewer having the potential to be retained through multiple selection years. In a university or private breeding program, less desirable lines would be discarded. We anticipate that direct market farms will be able to market variable tuber types that are less desirable, so that their participation in a breeding program will enable selection of adapted varieties without harming their production of saleable tubers.

Objective 1: Evaluate the practical and economic feasibility of on-farm production of high quality seed potatoes from minitubers and foundation class seed potatoes.

a. Field production of seed potatoes from minitubers and saved seed tubers

Minitubers were obtained from the Lelah Starks Elite Foundation Seed Potato Farm for 5 varieties: Red La Soda, Carola, French Fingerling, Austrian Crescent, and Yukon Gold. Four participants (Stoney Acres Farm, Athens WI; Lac Courte Oreilles Community College Farm, Hayward, WI; Paradox Farm, Ashby MN; and White Earth Land Recovery Project, Callaway, MN) planted trial plots of 40 or 80 minitubers per variety. Plots were managed according to the farmers’ usual practices, with the exception that minitubers were planted shallowly due to their small size. At Stoney Acres Farm and LCOCC Farm, minitubers were planted into rows within a larger field. At other locations, minitubers were planted into beds and managed by hand. Minitubers planted at Paradox Farm were grown under a heavy mulch in a garden environment. Tuber harvests were evaluated for usable yields, and farmers from White Earth LRP and Paradox Farm saved tubers for replanting in 2016.

b. Hoophouse and greenhouse production of seed potatoes from minitubers

Two participants trialed greenhouse and hoophouse production of seed potatoes from minitubers: Snug Haven, a direct-market farm with over an acre of year-round hoophouse production in Dane County, WI, and Hillview Urban Agriculture Center, an urban non-profit farm in La Crosse, WI. Hillview UAC provides community education on growing, preparing and preserving food. The Hillview UAC greenhouse is used to propagate plants for their annual plant sale, and for microgreen production, from fall until mid-June, and then is under-utilized over the summer. This provides an opportunity to use the space for production of high quality seed potatoes in a protected environment.

Participants were provided with minitubers for heirloom varieties from the Seed Savers Exchange collection that we had produced in a conventional greenhouse hydroponic system, using pathogen-free tissue culture plants as starting material. In 2017, both participants trialed two red varieties, Early Bangor and Cherries Jubilee. Snug Haven also trialed a white variety, Hunter, and a blue-fleshed variety, Nova Scotia Blue. In 2018, three heirloom varieties were trialed at Snug Haven: Barbara (multicolored), Gold Coin (yellow), Atlin Blue (blue fleshed); and a new breeding line designated PxC (red). At Snug Haven Farm, minitubers were planted in mid-March in 2017 and late-March in 2018. In 2017, tubers were harvested in mid-June except for later maturing Nova Scotia Blue which was harvested in mid-July. In 2018, tubers were harvested in late June. Snug Haven Farm aims to maximize the profitability of their limited growing space, and the potato harvest was timed to ensure they would be first at the local farmers’ market with new potatoes. At Hillview UAC, minitubers were planted in their certified organic greenhouse on July 5 and harvested in October. The center also produces vermicompost and vermicompost tea and used the minitubers to test the effect on yield of (1) adding vermicompost to their usual potting mix (Promix) and (2) irrigating plants in their usual potting mix weekly with vermicompost tea. Sampled tubers from harvests at both farms were grown for Potato Virus Y tests to determine whether harvests met standards for seed potato certification.

c. On-farm production of seed potatoes from foundation seed potatoes

Since yields from minituber planting stock in on-farm trials were generally low, we trialed production from foundation seed potato stock, the grade of potatoes planted by growers of certified seed potatoes. Foundation seed potatoes were obtained from the Lelah Starks State Seed Potato Farm (Rhinelander, WI), and each participant selected their preferred varieties to trial. Foundation seed potatoes were planted in small plots within participants’ usual potato fields and managed according to their usual practices. Farmers provided samples of harvested tubers for Potato Virus Y (PVY) testing.

In 2016, four farms committed to saving and replanting seed potatoes in 2017. For two of these farms, levels of PVY were sufficiently high in multiple seedlots to make replanting inadvisable. The two other farms replanted 5 lb of saved seed potatoes in comparison to 5 lb of certified seed potatoes purchased from Vermont Valley Community Farm (Dietz – variety Adirondack Red; Mortimore – variety Carola). Since the Wisconsin Senate Bill 23, passed in August 2017, requires farms who grow more than 5 acres of potatoes to plant certified seed potatoes, farms were not able to replant saved potatoes in 2018.

Objective 2: Provide training, coordination and resources for a farmer-participatory potato breeding network.

a. Selection of outstanding potato lines from true seed populations

True potato seed populations were derived either from crosses or from “open-pollinated” berries for which only the female parent was known. Many of these “open-pollinated” seeds were likely from self-pollination. Parents were selected for previous good performance in organic potato variety trials and for desirable traits such as Potato Virus Y (PVY) resistance. In each year of the project, true potato seeds were distributed to participating growers. Growers were advised on methods to start and select healthy potato seedlings. Growers started seedlings indoors, and transplanted seedlings 1-2 times into larger pots before transplanting seedlings to field beds. Grower selections at harvest were based on productivity, appearance, and if production allowed, eating quality. Seedlings for these and other populations were also planted in the organic seed potato production field at West Madison Agricultural Research Station and outstanding lines were selected based on productivity, appearance, and eating quality.

b. Mixed progeny populations as seed tubers

In 2016, seven participating growers trialed progeny populations from crosses for productivity and marketability, as a test of the feasibility of using true potato seed (TPS) as the basis for a production system. Since potatoes do not breed true, potatoes derived from TPS are less uniform than those from standard clonal propagation of varieties, and are likely to be more suited to direct markets such as CSA farms, which anecdotally report more acceptance of unusual produce. Growers were asked to answer the following questions: would they want to grow these populations again; what were the strongest and weakest points; and to rate the marketability and eating quality (1-5 scale with 5=best).

Objective 1: Evaluate the practical and economic feasibility of on-farm production of high quality seed potatoes from minitubers and foundation class seed potatoes.

a. Field production of seed potatoes from minitubers and saved seed tubers

Two participants planted minitubers into rows in a larger field setting. At both sites, weed pressure impacted the trials. At Stoney Acres Farm, weed density was greater in minituber plots than in neighboring plots. Although this trial was not designed to compare yields from minitubers and certified seed potatoes, it was noticeable that yields from minituber plots were much lower than yields in neighboring rows that had been planted with certified seed potatoes. At LCOCC Farm, weed pressure overwhelmed minituber plantings. Harvests from these plots were very low, and the farm manager decided not to replant. Due to their small size, plants from minitubers are typically smaller and less vigorous than plants from field-grown seed potatoes, and if shaded by early weed pressure, may not be able to produce well.

At Paradox Farm, minitubers were planted into heavily mulched beds. Yields for Carola, French Fingerling, and Red La Soda were rated well by the farmer, and tubers were saved for replanting, but Yukon Gold did not yield well and was not saved. At White Earth LRC, minitubers were planted into beds and managed with hand cultivation. All four varieties gave low yields (Table 1).

Table 1: White Earth Land Recovery Project field and harvest observations for plots planted with minitubers

|

Variety |

In-season observations |

Total yield per plant (lb) |

Marketable yield per plant (lb) |

Notes on harvested tubers |

|

Yukon Gold |

Good sized plants; not all emerged |

0.20 |

0.20 |

Mix of sizes |

|

French Fingerling |

Good vigor |

0.15 |

0.15 |

Good size |

|

Red La Soda |

Medium vigor |

0.18 |

0.18 |

Many small tubers |

|

Austrian Crescent |

Good vigor |

0.19 |

0.19 |

|

|

Carola |

Very vigorous |

0.29 |

0.27 |

|

In 2016, saved tubers for Red La Soda and French Fingerling were replanted at White Earth LRP, with 30 plants for each variety. Certified seed potatoes for varieties Red La Soda and Carola were grown as comparisons. In addition to saved seed potatoes from minituber plantings, the farmer at White Earth LRP replanted saved seed for four other varieties, Purple Pelisse, Picasso, Barbara, and Dark Red Norland, that had been part of a 2015 potato variety trial. Although the seed potatoes planted in this 2015 trial were not certified seed potatoes, they were produced from disease-free minituber stock in 2014, and the crop was closely inspected for evidence of disease.

Yields for replanted tubers for Red La Soda were comparable from saved and certified seed sources. No comparison to certified seed was made for French Fingerling, but the marketable yield was comparable to other varieties grown at White Earth (Table 2). However, high levels of common scab, a tuber defect caused by the soil bacterium Streptomyces scabies, were noted for unmarketable French Fingerling tubers.

Table 2: Yields from saved and certified seed potatoes at White Earth Land Recovery Project

|

Seed potato source |

Variety |

Total yield per plant (lb) |

Marketable yield per plant (lb) |

Unmarketable tuber causes |

|

Saved |

Red La Soda |

1.1 |

1.1 |

Na |

|

Certified |

Red La Soda |

1.43 |

1.4 |

animal damage |

|

Saved |

French Fingerling |

2.1 |

1.2 |

common scab |

|

Saved |

Purple Pelisse |

1.3 |

1.3 |

Na |

|

Saved |

Picasso |

2.1 |

1.7 |

insect |

|

Saved |

Barbara |

1.55 |

1.3 |

not recorded |

|

Saved |

Dark Red Norland |

0.5 |

0.5 |

Na |

At Paradox Farm, saved potatoes for varieties Carola, French Fingerling, and Red La Soda were replanted in 2016 and 2017. Yields were reported to be comparable to other varieties grown by the farmer.

b. Hoophouse and greenhouse production of seed potatoes from minitubers

In both 2017 and 2018, hoophouse grown plants at Snug Haven Farm were harvested between mid-June and mid-July. For all varieties except the breeding lines PxC, vines were still green at harvest. PxC vines had senesced naturally at harvest. One tuber was sampled from each plant for Potato Virus Y tests, and a zero incidence of PVY was seen for each variety in each year. Yields of new potatoes were low relative to main harvest field production, but the farmer was satisfied with yields due to the premium price obtainable for early potatoes at Madison WI farmers’ markets ($5/lb). It was clear that much higher yields could be obtained for all varieties with another month of growth.

Table 3: Potato yields for Snug Haven organic hoophouse production

|

Trial year |

Variety |

Days from planting to harvest |

Marketable yield per plant (lb) |

|

2017 |

Early Bangor |

80 |

0.49 |

|

Hunter |

80 |

0.43 |

|

|

Cherries Jubilee |

109 |

* see note below |

|

|

Nova Scotia Blue |

80 |

0.26 |

|

|

2018 |

Atlin Blue |

86 |

0.55 |

|

100 |

0.72 |

||

|

Barbara |

86 |

0.51 |

|

|

100 |

0.59 |

||

|

Gold Coin |

86 |

0.72 |

|

|

100 |

0.77 |

||

|

PxC |

86 |

0.73 |

|

|

100 |

0.99 |

*Cherries Jubilee was harvested later than other varieties in 2017 due to its later maturity. Yield was reported by the famer to be comparable to Early Bangor and Hunter.

At Hillview Urban Agriculture Center, yields of Corne de Mouton, Early Bangor and Cherries Jubilee suggest a positive effect of vermicompost on potato productivity (Table 4). Sampled tubers from harvests showed zero incidence of Potato Virus Y. However, since all the tubers stored by the center sprouted by the end of March, they were unable to trial replanting their saved tubers, and decided not to repeat the trial.

Table 4: Potato yields for Hillview organic greenhouse production

|

Variety |

Days from planting to harvest |

Yield (lb/plant) |

||

|

Promix |

Promix plus Vermicompost |

Promix plus Vermicompost tea |

||

|

Corne de Mouton |

98 |

0.35 |

0.56 |

0.50 |

|

Early Bangor |

105 |

0.84 |

0.92 |

0.79 |

|

Cherries Jubilee |

114 |

0.68 |

0.90 |

0.65 |

At the Bad River Indian Reservation, we built on previous connections with Joy Shelble, 4-H Youth Development Coordinator, to provide seed potatoes for planting in the youth-managed hoophouse, as a small pilot trial in 2017. Despite the late July planting, the early December harvest, used for a dinner at a community event, was substantial enough that the group participated in hoophouse variety trials in 2018 (supported by a separate grant). Bad River is an extremely economically disadvantaged community, and production of high quality seed potatoes within the community has the potential to increase local food production, impacting human nutrition and quality of life.

c. On-farm production of seed potatoes from foundation seed potatoes

Foundation seed potatoes were planted in small plots within participants’ usual potato fields and managed according to their usual practices. Farmers provided samples of harvested tubers for Potato Virus Y (PVY) testing. Potato Virus Y incidence from farms that planted foundation seed potatoes is summarized in Tables 5 (2016 trials) and 7 (2017-2018 trials) below.

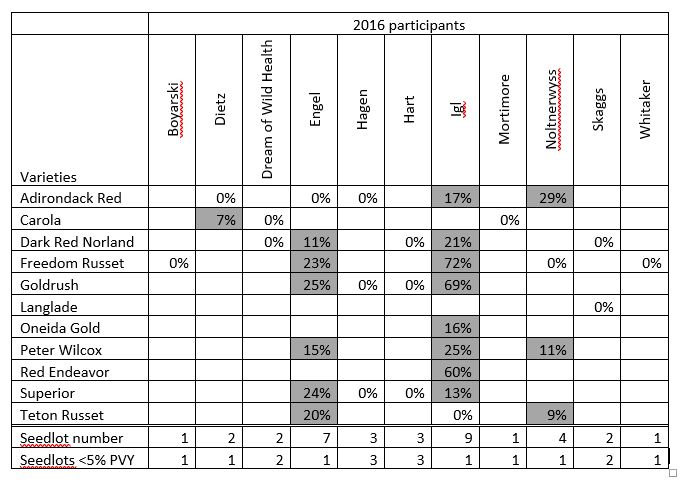

Of the 11 farms participating in 2016, 7 had no PVY incidence in tested tubers. Three (Engel, Igl and Noltnerwyss) had high PVY incidence in all or most seedlots that would preclude replanting, and the remaining farm (Dietz) had intermediate PVY incidence in one seedlot. It is notable that the three farms with high PVY incidence in 2016 grow substantially larger acreages than the other participants.

Table 5: Potato Virus Y (PVY) incidence in 2016 potato harvest from foundation seed potato stock, by farm and variety. All seed potatoes planted were foundation class (<0.5% PVY).

Two of the farms that had committed to replanting saved tubers had high levels of PVY in multiple seedlots, which made replanting inadvisable (Noltnerwyss, Igl). A third farm replanted comparisons of saved and certified seed ptoatoes but lost all plots due to extensive flooding. The Mortimore farm (Orange Cat Community Farm, in central WI) replanted 5 lb of saved Carola seed potatoes for which no PVY was detected, in comparison to 5 lb of certified seed potatoes purchased from Vermont Valley Community Farm. They additionally replanted saved Goldrush and Dark Red Norland seed potatoes (grown in 2016 from certified, not foundation stock) in comparison to certified seed potatoes of each variety. Farmer observations were that emergence, crop vigor, and yield were comparable between saved and certified seed potato sources for Carola and Dark Red Norland, but that saved Goldrush seed potatoes had “much lower vigor than normal” and “slow emergence”. Marketable yields were lower for plots planted with certified seed compared to saved seed (Table 6), but it should be noted that due to wet spring weather, planting of certified seed potatoes was delayed by two weeks after planting of saved seed potatoes, and this would account for the lower yields.

PVY incidence in samples from plots planted with certified seed potatoes (5% virus threshold) were at or almost at 100% for all three varieties, indicating substantial virus spread within the crop after planting. PVY incidence in plots from saved Goldrush seed potatoes (unknown starting incidence) were also at 100%, but PVY incidence in plots from saved Dark Red Norland (unknown starting incidence) and Carola (0% PVY starting incidence) seed potatoes were much lower at 12.8% and 0% respectively.

Table 6: Yields and PVY incidence for potato plots planted with either saved seed potatoes or certified seed potatoes at Orange Cat Community Farm.

|

Variety |

Seed source |

Marketable yield (lb/row foot) |

PVY incidence (%) |

|

Carola |

Saved from foundation stock, 0% PVY) |

1.75 |

0% |

|

Carola |

Certified |

0.94 |

91.5% |

|

Dark Red Norland |

Saved from certified stock, not tested for PVY |

1.75 |

12.8% |

|

Dark Red Norland |

Certified |

0.93 |

89.6% |

|

Goldrush |

Saved from certifed stock, not tested for PVY |

1.15 |

97.9% |

|

Goldrush |

Certified |

0.92 |

95.8% |

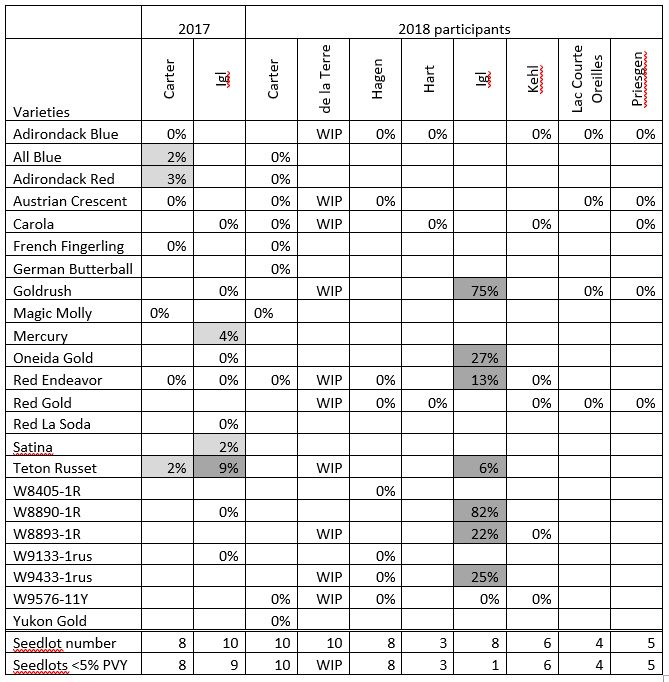

In 2017, 2 farms participated in seed potato trials, and both had low PVY incidence in seedlots (Table 7). At Igl Farms, 9 of 10 varieties were below the virus incidence standard for certified seed potatoes, with 7 varieties having no PVY detected in sampled tubers. At Carter Farms, all 8 varieties grown from Wisconsin foundation seed were certified as seed potatoes, with 5 having no detectable PVY. However, in 2018 (Table 7), while all seedlots from 7 of the participants were free of PVY, only one seedlot from the Igl farm was PVY-free, with all 8 other seedlots having high PVY incidence ranging from 13-72%.

Table 7: Potato Virus Y (PVY) incidence in 2017 and 2018 potato harvests from foundation seed potato stock, by farm and variety. All seed potatoes planted were foundation class (<0.5% PVY). WIP= work in progress.

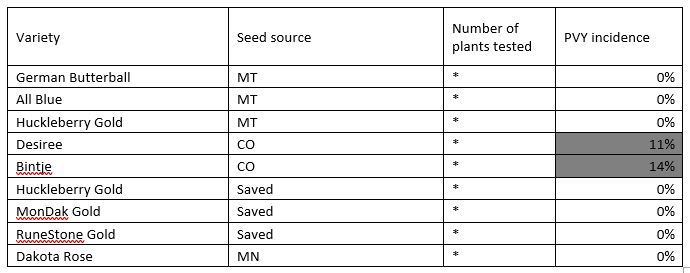

In 2017, Carter Farms provided PVY incidence data for 9 other seedlots planted with foundation seed from Colorado (2 seedlots, failed certification), Montana (3 seedlots, passed certification), Minnesota (1 seedlot, passed certification) and their own saved foundation grade seed potatoes (3 seedlots, passed certification).

Table 8: Varieties tested in 2017 at Carter Farms only

Yields from foundation seed stock were recorded at Igl Farms in 2017 and 2018 (Table 9). Some varieties were rejected by farmers due to tuber defects (Carola, Mercury and Red La Soda 10) or failed due to seedpiece decay (W8890-1R). In 2017, marketable yields from acceptable varieties ranged from 1.6-2.6 lb per row foot. In 2018, yields were considerably lower, possibly due to drought conditions, ranging from 0.4-1.0 lb per row foot.

Table 9: Yields from plots planted with foundation seed at Igl Farm, Antigo WI

|

Year |

Variety |

Marketable yield (lb per row foot) |

B size yield (lb per row foot) |

Farmer comments |

|

2017 |

Carola |

0.0 |

0.3 |

Not graded - shape defects |

|

Goldrush |

2.6 |

0.4 |

|

|

|

Mercury |

0.8 |

0.4 |

Too small |

|

|

Oneida Gold |

1.8 |

0.3 |

|

|

|

Red La Soda 10 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Not graded - high scab incidence |

|

|

Teton Russet |

1.6 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

W9133-1rus |

2.0 |

0.5 |

Yellow skin, greening, scab |

|

|

2018 |

Goldrush |

0.8 |

0.1 |

|

|

Oneida Gold |

0.9 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

Red Endeavor |

1.0 |

0.1 |

|

|

|

Teton Russet |

0.4 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

W8890-1R |

0.1 |

0.0 |

Poor stand - seedpiece decay |

|

|

W8893-1R |

0.4 |

0.1 |

|

|

|

W9433-1rus |

0.8 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

W9576-11Y |

0.9 |

0.1 |

|

Objective 2: Provide training, coordination and resources for a farmer-participatory potato breeding network.

a. Selection of outstanding potato lines from true seed populations

Parental lines for true potato seed populations were selected due to good performance in previous organic variety trials, and several lines were included based on their resistance to Potato Virus Y. Parental lines are listed in Table 10.

Table 10: Potato varieties used as parents for true potato seed populations

|

Variety |

Characteristics |

|

Adirondack Blue |

Blue skin and flesh |

|

Adirondack Red |

red skin and flesh |

|

Aylesbury Gold |

yellow, PVY resistant, heirloom |

|

Barbara |

yellow with purple splashes, PVY resistant |

|

Blue Victor |

blue and white skin, white flesh, heirloom, extremely high yielding |

|

Carola |

Yellow round; good flavor |

|

Chieftain |

Red round |

|

Dark Red Norland |

red, some PVY resistance, early maturity |

|

Early Bangor |

red skin, white flesh, heirloom, high yielding |

|

Fenton Blue |

Blue skin and flesh, heirloom |

|

Huckleberry |

Red skin and flesh, heirloom (not same as Huckleberry Gold) |

|

Langlade |

White round; high yielding |

|

Papa Cacho |

large red fingerling, Peruvian indigenous variety |

|

Picasso |

yellow with red splashes, PVY resistant, high yielding |

|

Purple Pelisse |

purple skin and flesh |

|

Red Endeavor |

Red round |

|

Red Thumb |

red fingerling with pink flesh, heirloom |

|

Spartan Splash |

yellow and purple skin, PVY resistance |

|

Sweet Yellow Dumpling |

yellow skin and flesh, heirloom |

|

White Lady |

White, PVY resistance |

|

Yellow Rose |

smooth red skin, yellow flesh, heirloom |

|

Yukon Gold |

Yellow, early maturity |

Three participating farmers selected lines from true potato seeds to replant. Results from the initial selection year are shown in Table 11. Yields from plants started from seed ranged from 0.09 to 1.89 lb/plant across the three sites. Participants selected tubers to save and replant in the following year (Table 12).

Table 11: Yields from potato lines started from botanical seed at three sites. Potato lines were trialed at White Earth Land Recovery Project by Zachary Paige in 2015 and 2016; at Middleton Outreach Ministry Community Garden by Pat Dunn in 2017 and 2018; and by Wausau WI trial participant Paul Whitaker in 2017 and 2018. *True potato seed collected by Zachary Paige in 2015.

|

Female parent |

Male parent |

Trialer |

Selection year |

Number of plants |

Yield per plant (lb) |

Comments |

|

Carola |

Chieftain |

Paige |

2015 |

20 |

1.20 |

Equal proportions of red, yellow and orange colored tubers |

|

Carola |

Dark Red Norland |

Paige |

2015 |

10 |

1.30 |

Dented shape, equal proportions of red and orange colored tubers |

|

Carola |

Yukon Gold |

Paige |

2015 |

20 |

0.80 |

|

|

Keuka Gold |

Chieftain |

Paige |

2015 |

15 |

0.63 |

Equal proportions of red and yellow tubers |

|

Yukon Gold |

Chieftain |

Paige |

2015 |

10 |

1.28 |

Multicolor (50%), red and yellow tubers (25% each) |

|

Barbara |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

25 |

0.29 |

|

|

Dark Red Norland |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

15 |

0.17 |

|

|

Makah |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

23 |

0.57 |

|

|

Purple Pelisse |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

14 |

0.24 |

|

|

Red Thumb |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

22 |

0.09 |

|

|

Yellow Rose |

OP |

Paige |

2016 |

14 |

0.31 |

|

|

Carola x Dark Red Norland |

OP |

Paige* |

2016 |

8 |

0.34 |

|

|

Carola x Yukon Gold |

OP |

Paige* |

2016 |

23 |

0.51 |

|

|

Keuka Gold x Chieftain |

OP |

Paige* |

2016 |

15 |

0.12 |

|

|

Aylesbury Gold |

Picasso |

Dunn |

2017 |

5 |

Nd |

|

|

Huckleberry |

Red Endeavor |

Dunn |

2017 |

5 |

Nd |

red skin |

|

Spartan Splash |

Red Endeavor |

Dunn |

2017 |

5 |

Nd |

yellow and purple skin |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

Whitaker |

2017 |

14 |

Nd |

|

|

Spartan Splash |

Picasso |

Whitaker |

2017 |

3 |

Nd |

|

|

Caribe |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

1 |

1.89 |

Thicker skin, slightly sweet taste |

|

King Harry |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

2 |

0.26 |

|

|

Oneida Gold |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

3 |

0.56 |

|

|

Picasso |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

4 |

0.53 |

|

|

Red Endeavor |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

3 |

0.86 |

Thin skin, nice texture, sweet and potato-y taste |

|

Red Thumb |

OP |

Dunn |

2018 |

5 |

0.46 |

Thin skin, smooth texture, good potato-y taste |

Each participant selected tubers to save and replant based on yield, appearance and flavor. Yields and comments for replanted tubers are shown in Table 12. At White Earth Land Recovery Project, Zachary Paige saved tubers from multiple plants for each of 5 populations to replant in 2016. Yields ranged from 1.3 to 2 lb per plant. Eating quality of these lines was comparable to named varieties that he grew at the same location, and he continued to save and replant tubers for the Yukon Gold-Chieftain cross for another two years. Other participants saved tubers from individual plants representing clonal lines. Pat Dunn saved two lines to trial, from Spartan Splash x Red Endeavor and Huckleberry x Red Endeavor crosses respectively. Both have good eating quality and moderate yields, and will be trialed in 2019 at the West Madison Agricultural Research Station. Paul Whitaker trialed 9 lines in 2018; 7 from a Huckleberry x Picasso cross and 2 from a Spartan Splash x Picasso cross. Yields ranged from 1.5 to 3.8 lb per plant, and Paul selected 6 lines to trial again at his location as well as at the West Madison Agricultural Research Station in 2019.

Table 12: Yields and comments for farmer-selected potato breeding lines

|

Female parent |

Male parent |

Line |

Trialed by |

Selection year |

Yield per plant (lb) |

Comments |

Tubers saved for replanting |

|

Carola |

Chieftain |

na |

Paige |

2016 |

1.7 |

Best vine vigor of all varieties, minor pest damage |

|

|

Carola |

Dark Red Norland |

na |

Paige |

2016 |

2 |

Nice dark green color, |

|

|

Carola |

Yukon Gold |

na |

Paige |

2016 |

1.3 |

Nice vigor, all plants had early-mid maturity |

|

|

Keuka Gold |

Chieftain |

na |

Paige |

2016 |

1.5 |

Very nice uniform vigor |

|

|

Yukon Gold |

Chieftain |

na |

Paige |

2016 |

1.5 |

|

Yes, replanted in 2017 and 2018 |

|

Spartan Splash |

Red Endeavor |

na |

Dunn |

2018 |

1.1 |

Cream colored flesh, very smooth and tasty. |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Red Endeavor |

na |

Dunn |

2018 |

1.8 |

thin skin, attractive yellow and purple pattern |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

10 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

2.9 |

smooth red skin, pink and yellow flesh, average taste |

no; too much greening and scab |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

11 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.5 |

attractive yellow skin with magenta patches, very yellow moist and mealy flesh, good flavor |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

13 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.2 |

yellow skin with magenta patches, white flesh, good taste, creamy |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

14 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

2.1 |

red skin, good flavor |

no, low yield and scab |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

2 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.5 |

red skin, mealy texture, excellent flavor |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

3 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.5 |

attractive red skin, yellow flesh w/ pink swirls, earthy distinctive flavor, good |

Yes |

|

Huckleberry |

Picasso |

6 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

1.5 |

red skin |

no, cooked texture wet & crisp like boiled turnip |

|

Spartan Splash |

Picasso |

1 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.8 |

yellow skin, white flesh, large tubers, good flavor, minimal scab |

Yes |

|

Spartan Splash |

Picasso |

3 |

Whitaker |

2018 |

3.3 |

yellow skin, yellow flesh, minimal scab and uniform shape, nice flavor with moist texture |

Yes |

Lines shown in Figure 1, in addition to 5 other farmer-selected lines mentioned above, will be trialed at the West Madison Agricultural Research Station in 2019 as part of a Specialty Crop Block Grant-funded project.

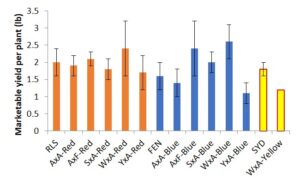

In 2015, breeding lines were selected from mixed progeny populations for the crosses described above, plus selfing of Adirondack Blue (AxA series), crosses of Eva (a Potato Virus Y resistant variety) with breeding line 118, and crosses of Keuka Gold with Yukon Gold (KKGxYKG). Breeding lines were planted in plots of 5-10 plants (depending on availability of seed potatoes) in the West Madison Agricultural Research Station organic field in 2016. Two parental varieties were also planted – Fenton Blue (FEN) and Sweet Yellow Dumpling (SYD) – as well as a widely adapted check variety, Red La Soda (RLS); these varieties were planted in replicated plots whereas single plots were planted for the breeding lines. As shown in Figure 2, several lines had marketable yields substantially above the parental lines. Due to a late blight outbreak in September, tubers from these lines were not saved for 2017 field trials, but healthy tubers were selected for introduction into tissue culture.

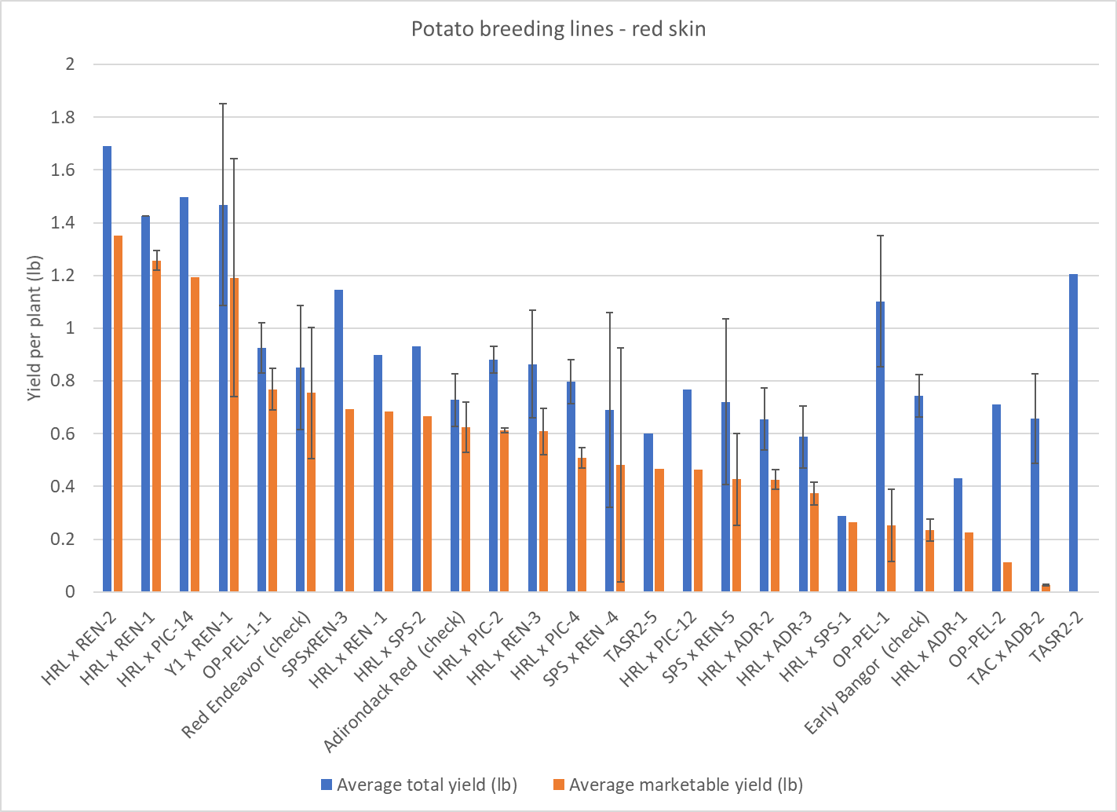

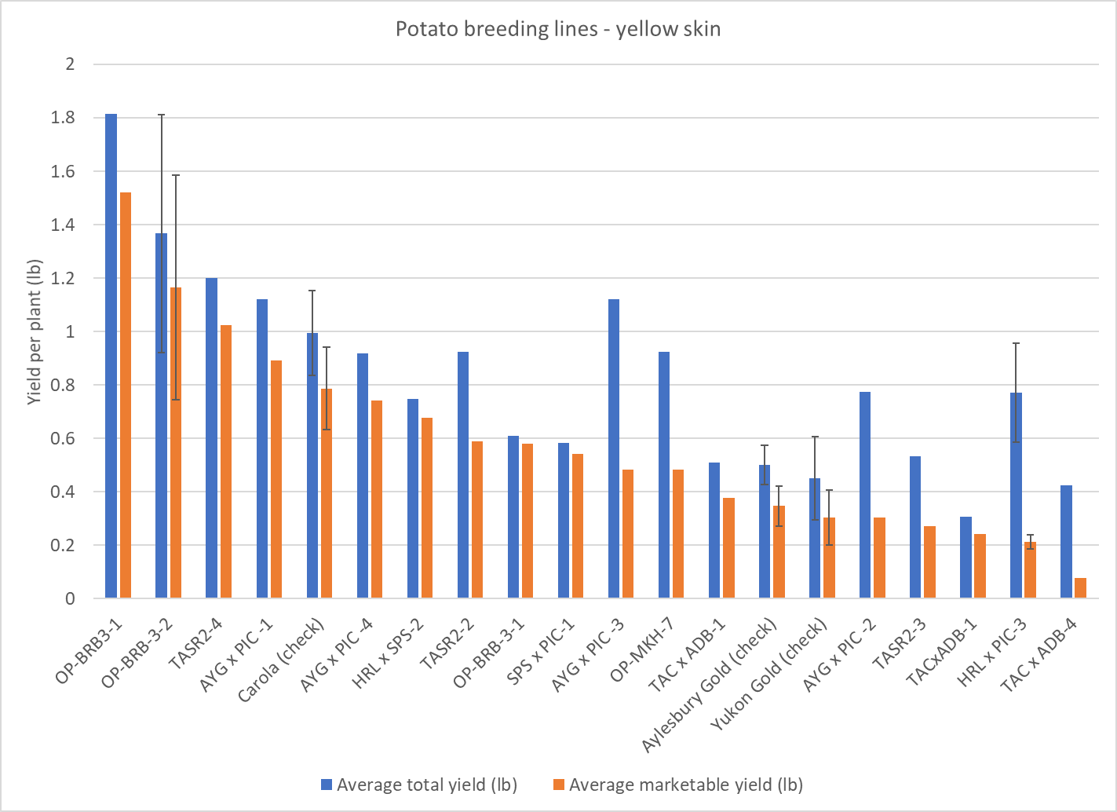

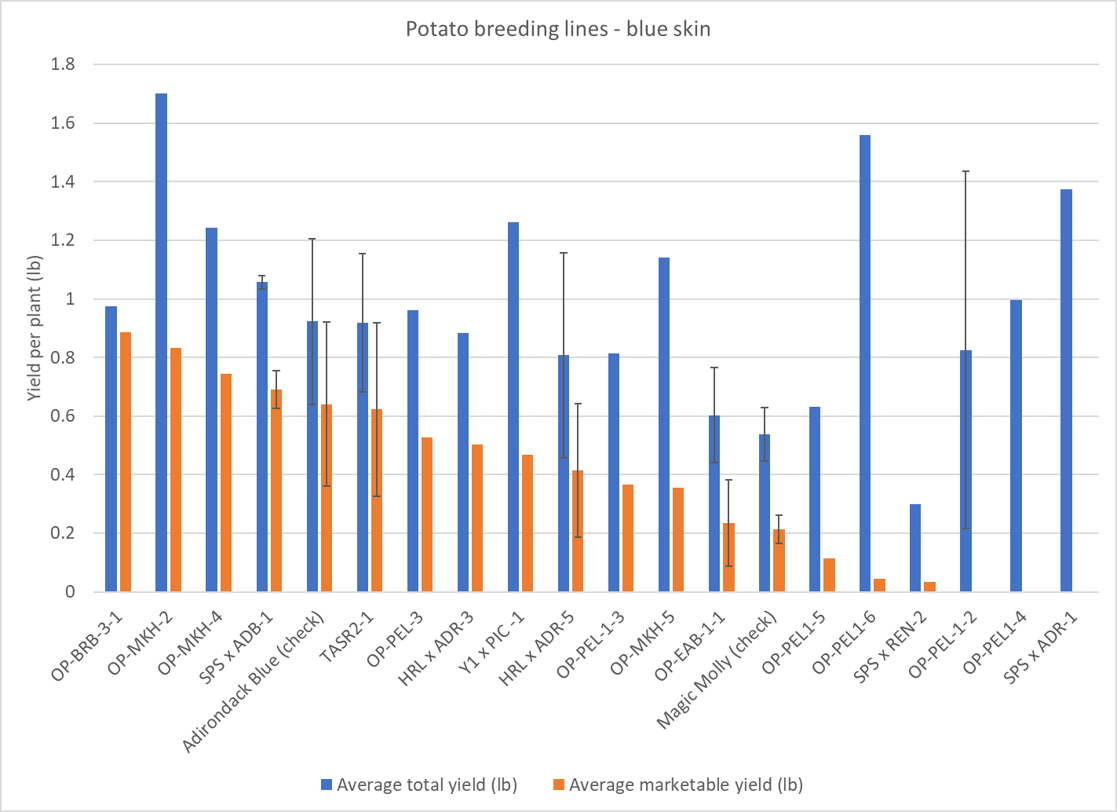

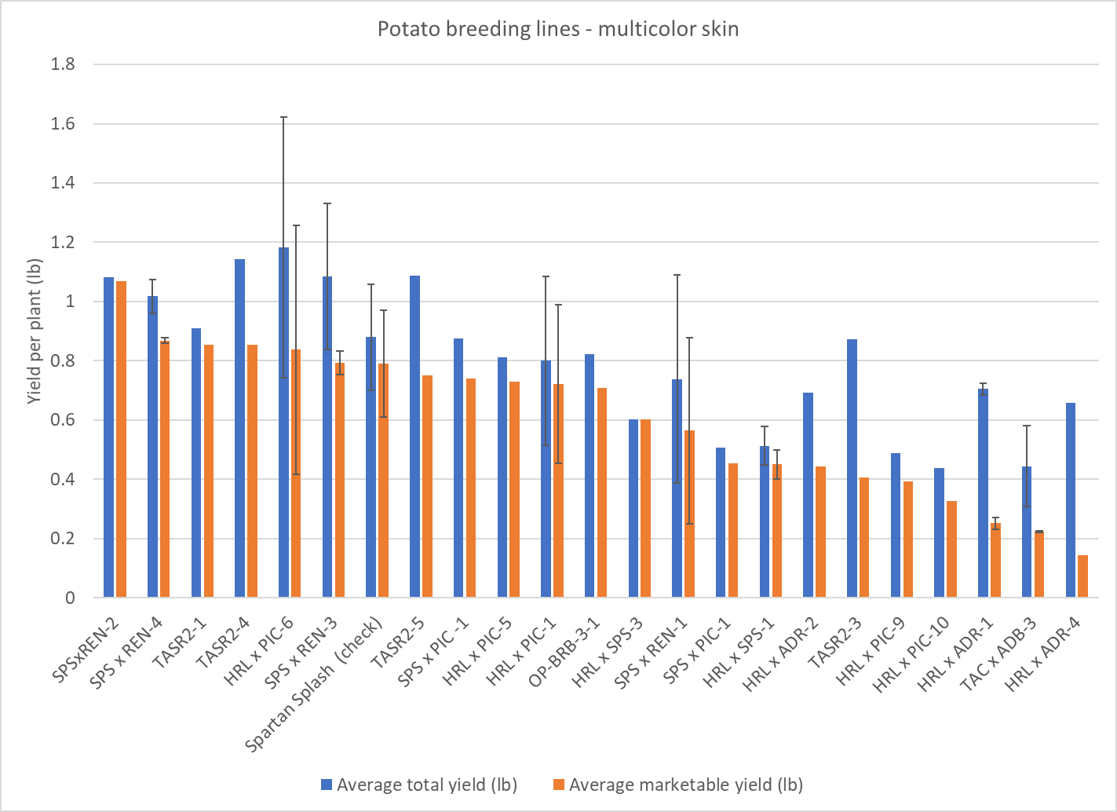

In 2016, minitubers for 14 breeding populations were planted in the organic seed potato production field at West Madison ARS. Seven of these populations derived from crosses between Potato Virus Y-resistant lines (PVYR; resistance derived from Eva, Tacna, or White Lady) and popular varieties including Carola, Adirondack Blue, Red La Soda, and Spartan Splash. The other seven populations were open-pollinated populations from female parents Aylesbury Gold (PVYR), Barbara (PVYR), Picasso (PVYR), Early Bangor, Makah, Purple Pelisse, and Red Thumb. Total yield data was collected for each population and averaged 0.85 lb/plant, ranging from 0.3 to 1.9 lb/plant. Although late blight incidence in nearby plots ruled out saving tubers for field trials, select tubers were collected for introduction into tissue culture and future trials. In 2017, minitubers for a set of breeding populations was multiplied in the organic seed potato production field at West Madison ARS, and tubers for individual plants were selected for replanting. Breeding populations were derived from the following varieties, as shown in Figure 3 legends and Table 10, either as crosses or from open pollinations (OP): Aylesbury Gold (AYG), Adirondack Blue (ADB), Adirondack Red (ADR), Barbara (BRB), Early Bangor (EAB), Huckleberry (HRL), Picasso (PIC), Purple Pelisse (PEL), Red Endeavor (REN), Spartan Splash (SPS), Tacna (a PVY resistant breeding line, TAC), and Y1 (a PVY resistant breeding line). Lines abbreviated "TASR" are from crosses between an F1 plant from a Tacna x Adirondack Blue cross and an F1 plant from a Spartan Splash x Red La Soda cross. These lines were trialed under organic management in 2018 at West Madison ARS. Most lines were planted as single plots due to limited tuber quantities, in comparison to replicated check varieties. Total and marketable yields for four market classes are shown in Figure 3 A-D.

b. Mixed progeny populations as seed tubers

In 2016, seven participating growers trialed progeny populations from crosses for productivity and marketability, as a test of the feasibility of using true potato seed (TPS) as the basis for a production system. Growers were asked to answer the following questions: would they want to grow these populations again; what were the strongest and weakest points; and to rate the marketability and eating quality (1-5 scale with 5=best). Grower feedback is shown in Table 13.

Table 13: Grower evaluations of mixed progeny populations from potato crosses Adirondack Blue and Fenton Blue (AxF series), Sweet Yellow Dumpling and Adirondack Blue (SxA series), White Lady and Adirondack Blue (WxA series) and Yellow Rose and Adirondack Blue (YxA series).

|

Cross |

Tuber color |

# growers |

# willing to grow again |

Average marketability (out of 5) |

Average eating quality (out of 5) |

Strongest point |

Weakest point |

Other comments |

|

AxF |

Purple |

1 |

1 |

5 |

3.5 |

Color |

Variable size, mealy |

Waxy, not good for frying or baking |

|

AxF |

Red |

1 |

1 |

5 |

5 |

Color (hot pink skin, yellow flesh) |

Lower yield |

Striking color, starchy enough to be good multi-purpose, good fryer |

|

SxA |

Purple |

1 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

Multi purpose |

Small sizes |

|

|

SxA |

Yellow |

1 |

Maybe |

3 |

4 |

Good baked |

Odd shapes and sizes |

Many small |

|

WxA |

Purple |

4 |

4 |

4.75 |

4.5 |

High yield, good tuber size; generally attractive shape and skin |

Wide spread of stolons, shallow tuber set |

Variable but generally good looking, customers loved; long season; high incidence of hollow heart |

|

WxA |

Red |

3 |

2 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

Color (purple skin, yellow flesh); creamy texture; mix of sizes and shapes |

Crumbled when baked; variable yield |

Good baker |

|

WxA |

Yellow |

1 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

Very productive |

Greened in storage |

|

|

YxA |

Purple |

1 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

Color |

Inconsistent color and shapes |

Waxy |

|

YxA |

Red |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

For 14 trials of mixed populations, 11 were acceptable to growers to grow again, with one "maybe". Of the 9 populations, 4 rated higher than average for marketability, and 6 rated higher than average for eating quality. Populations derived from crosses Adirondack Blue x Fenton Blue (red tubers) and White Lady x Adirondack Blue (red, purple and yellow tubers) were the most promising.

Objective 1: Evaluate the practical and economic feasibility of on-farm production of high quality seed potatoes from minitubers and foundation class seed potatoes.

Since minituber production in greenhouse conditions is more economically scaleable than field production of foundation seed potatoes, use of minitubers as planting stock for organic seed potato production has potential to increase the diversity of varieties available in appropriate quantities for organic growers. On-farm trials demonstrated that field production of seed potatoes from minitubers under organic management requires more intensive weed management than for potatoes produced from regular seed tubers. Minitubers produce less vigorous plants that are easily outgrown by weeds. Minituber production for the conventional seed potato system aims for a 0.5-1 inch minituber. Larger minitubers produce more vigorous plants and may be more successful in organic systems. Also, close spacing and/or early weed management may allow canopy closure of the potato crop sufficient to shade out weeds.Future research could investigate minituber size, plant spacing and timing of weed management needed for organic field production from minitubers.

Planting minitubers in beds appears more successful than field production. Saved tubers yielded comparably to regular certified seed potatoes at two locations. Yields at White Earth Land Recovery Project averaged 0.2 lb across 5 varieties, sufficient to replant only 1-2 plants. Improved yields would make seed potato production from minitubers a more worthwhile enterprise at this location. However, since the average weight of minitubers was 6-12 g (0.2-0.4 oz), the reduction in seed potato shipping costs is significant for isolated locations.

Hoophouse yields from minitubers ranged from a quarter to one pound per plant depending on variety and plant maturity. No Potato Virus Y was detected in sampled tubers, indicating good potential for production of high quality seed potato tubers. In 2018, comparison of yields at early and later hoophouse harvests showed that much higher yields could be obtained for all varieties with another month of growth. However, later harvest increases the risk of reduced seed potato quality due to the potential for aphid transmission of potato viruses; viruliferous aphid populations peak in the Upper Midwest in July-August. To increase the growing season and yield potential while avoiding aphid-borne viruses, an earlier planting date would be feasible in hoophouse conditions, but the farm’s intensive use of space to maximize hoophouse profitability discourages the farmer from risking space on an unproved proposition. Ideally, in future research we will evaluate potato production from minitubers in a University-owned hoophouse so that multiple planting and harvest dates can be evaluated for impact on yield and seed potato quality.

Adequate storage for seed potatoes is necessary to maintain dormancy until the following spring. Seed potatoes are stored in high humidity at temperatures from 34-36 F. While early harvest of seed potatoes may avoid aphid-borne viruses, it also necessitates up to 11 months of seed potato storage. This is a possible disadvantage of early season hoophouse or greenhouse production of seed potatoes.

In field production, Potato Virus Y (PVY) is the most common cause for potato seedlots to fail certification. PVY is spread by certain aphid species and is carried in tubers from infected plants. In trials of seed potato production from foundation seedlots, PVY incidence was highly variable between farms and years in the 3 years of the study. Farms with high PVY incidence in 2016 and 2018 grow larger acreages of potatoes than most other participants and are close to large scale conventional potato acreages where viral inoculum is more likely to be present in neighboring fields. One of these farms, Igl, participated in all three trial years. Although overall PVY incidence was considerably lower in 2017 than 2016 and 2018, two seedlots showed PVY incidence, and one of these had greater than 5% incidence which would cause it to fail seed certification. Participants growing smaller acreages of potatoes more isolated from large scale potato production had lower or no incidence of PVY, potentially due to isolation from sources of viral inoculum.

Carter Farms (North Dakota) participated in 2017 and 2018 trials. Carter Farms are established seed potato growers who have recently obtained organic certification, making them the second organic seed potato growers in the North Central region. Like other seed potato growers, they are required to plant only foundation seed potatoes, reducing the level of viral inoculum on-farm compared to farms that plan certified or saved seed potatoes. In both years, all seedlots passed certification, with the exception of two seedlots; failure of these lots is likely related to seed source, as they were the only two planted with foundation seed potatoes that originated in Colorado.

While organic production of seed potatoes is clearly feasible, varietal characteristics and year-to-year variations (e.g. variation in abundance of virus-transmitting aphids or viral inoculum in neighboring fields) mean that failing seed potato certification is a real possibility. Conventional seed potato growers face similar risks, and like organic growers, they have recourse to ware potato markets to sell lots that fall below seed potato certification standards. Factors that increase the likelihood of successful seed potato production include isolation from potato growing regions, ensuring that all seedlots planted on-farm are virus free, and where possible, planting virus resistant varieties.

Objective 2: Provide training, coordination and resources for a farmer-participatory potato breeding network.

Nine farmers participated in on-farm selection of potato breeding lines for organic production. Three of these farmers selected lines directly from true potato seed populations, raising seedlings and transplanting them into their growing environment. Yields from seed-started plants are generally lower than from tuber-started plants, but yields showed sufficient variation for farmers to select better yielding lines as well as selecting on appearance. For most lines, there was insufficient production to allow selection on taste in the first year. Yields were substantially higher for lines in the second year of production when they were started from tubers, and several lines were discarded for below average taste. Eight lines will be maintained and entered into an ongoing potato selection and trialing network, beginning with trials at the West Madison Agricultural Research Station in 2019.

Breeding populations were also provided to farmers as mixed progeny from crosses, since this allowed growers to trial early breeding populations without raising plants from seed, and also since several participating direct market growers were curious to expose their customers to a more diverse selection of potatoes. Populations derived from crosses Adirondack Blue x Fenton Blue (red tubers) and White Lady x Adirondack Blue (red, purple and yellow tubers) were the most promising. These varieties will be used in future crosses to develop breeding populations. These trials indicate that there is potential for use of true potato seed as a starting point for organic potato production. As most potato pathogens cannot be transmitted through true potato seed, use of true potato seed can provide healthy planting stock as well as a diversity of tasty and colorful potatoes.

Education

Education on seed potato production and potato breeding was conducted primarily through one-on-one discussions during farm visits and phone conversations. Since terminology can be confusing, particularly since the word "seed" is used to refer both to seed potatoes ie tubers, and to botanical seed used for breeding, one-on-one explanations were beneficial to allow use of visual aids. Additionally, presentations at grower conferences including the MOSES Organic Farming Conference and the Indigenous Farming conference included explanations of seed potato production and potato breeding aimed at demystifying these processes.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

An article was published in the Jan/Feb 2015 Organic Broadcaster (https://mosesorganic.org/organic-potato-varieties/) to summarize previous research on potato variety selection, and introduce the seed potato production and breeding objectives of this project to a wide audience. This was followed by a blog article, “Potato Mixology” (http://labs.russell.wisc.edu/organic-seed-potato/2015/03/23/tps-trials/) written by farmer-collaborator Erin Schneider with editing help from Ruth Genger, to explain the process of starting and selecting potatoes from true seeds. This blog article will be developed into a factsheet. A video detailing potato crossing and seed cleaning is being developed.

In each year of the project (2015-2018), fall field days at West Madison and Spooner Agricultural Research Stations have been well attended by farmers, county extension agents, plant breeders and seed company representatives (approximately 60-80 and 30-40 attendees respectively). Attendees toured potato variety and breeding line trial plots (funded by this and a separate grant), heard research updates for on-farm seed potato production and potato breeding research trials, and were given handouts summarizing these research projects. A 2017 “Cool Tools” field day at Red Door Family Farm (Athens, WI) provided not only an opportunity to demonstrate an antique potato planter used in planting small scale research plots, but to share potato breeding and seed potato production research updates with attendees (approximately 50 farmers).

Farm visits have provided opportunities for practical demonstrations of applying selection criteria to achieve breeding goals, both in-season (e.g. symptoms of leafhopper damage, evaluation of canopy cover) and post-harvest (e.g. rapid estimates of tuber yield, identifying tuber defects). Over the course of the project, we have made multiple visits to farms including Whitewater Gardens Farm (2), Hungry Turtle Farm (1), Keppers Pottery and Produce (2), Maple Ridge CSA (1), Stoney Acres Farm (3), WeGrow Farm (2), LynDale (2), Boyarski Farm (1), Webster Farm Organic (1), Hillview Urban Agriculture Center (1), Roots and Shoots (2), Hilltop Community Farm (2), and Paradox Farm (1). At visits to Igl Farms (6) and Orange Cat Community Farm (3), we have discussed seed potato production needs.

Through this project, we have deepened connections with several farms serving indigenous communities. Tours of Dream of Wild Health (2), the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation community gardens (1), Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College Farm (3), and the Bad River Indian Reservation community garden (3) have provided opportunities to learn from farm managers and community members about food sovereignty initiatives, community food preferences (eg interest in purple-fleshed potatoes) and current opportunities and constraints to production, storage and distribution (eg new storage facilities, access to hoophouse; low soil fertility, limited agricultural equipment). Lac Courte Oreilles Farm and Dream of Wild Health have experimented with starting potatoes from true seed, and Dream of Wild Health have used these plants and the varying tuber types produced from them in their educational programs with school children to discuss plant breeding. White Earth Land Recovery Project staffer Zachary Paige is continuing to select and maintain potato breeding lines that he selected from true potato seeds in 2015. Successful potato production in the Bad River community garden hoophouse in 2017 is encouraging, especially since this represents an opportunity for seed potato production for the community.

Talks and presentations

Building Resilience and Flexibility into Midwest Organic Potato Production: Participatory Breeding and Seed Potato Production. Poster presentation at Our Farms, Our Future Conference, St. Louis MO, April 2018. Presented by Laura Jessee.

Healthy, Productive, Delicious: Choosing the Best Vegetable Varieties for Your Farm or Garden. Panel workshop at Indigenous Farming Conference, Callaway MN, March 2018.

Healthy, Productive, Delicious: Choosing the Best Vegetable Varieties for Your Farm or Garden. Panel workshop at Women, Food and Agriculture Network Annual Conference, Madison WI, November 2017.

Potatoes: Keeping diversity in the field through participatory plant breeding. Workshop at Indigenous Farming Conference, Callaway MN, March 2016.

On-farm Conservation of Genetic Diversity and Organic Plant Breeding. Panel presentation at Organic Seed Growers Conference, Corvallis OR, January 2016.

Improving the health and productivity of organic potato crops through participatory research. Talk at American Phytopathological Society annual meeting, Pasadena CA, August 2015.

Heirloom and specialty potatoes: Selecting varieties for organic production systems. Talk at Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association Grower Education Conference, Stevens Point WI, February 2015.

Roundtable, networking and seed swap events: At the 2017 and 2018 Organic Vegetable Production Conferences (January, Madison, WI), I facilitated roundable discussions of vegetable breeding priorities with 30+ growers (additional growers in other roundtable discussions of breeding priorities numbered 90+ in each year). At the MOSES Organic Conference in 2016, 2017 and 2018 (February, La Crosse, WI) we discussed priorities in organic potato breeding in a roundtable format with 10-15 vegetable growers. At the Indigenous Farming Conference (March 2016, 2017, 2018, Callaway, MN), I met with growers interested in seed potato production and breeding, many of whom farm or garden as part of food sovereignty initiatives on their reservations. I also participated in a seed swap event each year, using this event to distribute true potato seeds, discuss potato breeding and selection approaches, and distribute guides to potato seed collection, propagation and selection to 30+ interested participants in each year. It was encouraging in 2017 and 2018 to reconnect with several farmers who had obtained true potato seeds from me in the previous year, and had successfully grown and selected appealing potato lines. Also at IFC in 2018, I attended the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network meeting to learn from the discussion of food and seed sovereignty; I was able to respectfully contribute thoughts on the potential for potato breeding and production research to contribute to food sovereignty, and in particular connected with members of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, the White Earth Land Recovery Project, the Ho Chunk Nation, and the Experimental Farm Network.

Learning Outcomes

- Limited generation process of seed potato production

- Sampling harvested potatoes for disease testing

- Handling procedures for seed potatoes to limit disease spread

- Storage methods for seed potatoes

- Starting potato plants from botanical seed

- Selecting clonal lines from botanical seed

- Genetic diversity of potato types obtained from crossing clonal lines

Project Outcomes

Purchasing certified seed potatoes as a result of learning about spread of viral pathogens in-season and seeing viral incidence in harvested plots

Producing potatoes in a hoophouse environment to meet early season demands for new potatoes and as a rotational crop following spinach

Producing potatoes in a far Northern growing environment using a hoophouse to take advantage of the season extension possibilities

Expanding the range of varieties offered as certified seed potatoes

Growing potatoes from botanical seed to select attractive and good tasting new varieties

A beginning farmer from western Minnesota has experimented extensively with both seed potato production and potato breeding through this project. The skills and knowledge gained led him to apply successfully for funding for further trials of seed potato production with the intention of starting a certified seed potato business. He plans to continue breeding and selecting potatoes that thrive in his region.

A certified seed potato producer from eastern North Dakota who had recently transitioned land into organic management accessed a wider range of foundation seed potato varieties as a result of participation in this project. She was able to select varieties with good performance in her growing conditions and offer them for sale as certified organic, certified seed potatoes. Additionally, by having seed potatoes from several different sources, she was able to identify higher quality sources that were more likely to result in successful seedlot certification. She is now the second organic grower producing certified seed potatoes in the Upper Midwest, creating greater stability for the supply of organic seed potatoes regionally.

An organic farmer in southern Wisconsin has introduced potatoes into his hoophouse production, finding that they are a good rotation crop to follow fall-planted spinach. They can be harvested as very early season new potatoes which are popular and profitable at local farmers' markets, and they also disrupt the life cycle of symphylans, soil pests that impact spinach and other crops.