Final report for LNC16-382

Project Information

Cooperators

Research

The research in our project was not designed to test a specific hypothesis. Rather, it is meant to inform a planning process with a multi-sector group of stakeholders, with goals of diverting more food waste away from the landfill toward local and regional composting facilities, while ensuring sufficient demand for the resulting end products.

At the start of the project we identified 12 questions we hoped to answer through our research:

- What sources of food waste in Milwaukee are already being composted?

- Who is composting Milwaukee’s food waste now, and where?

- What are the most promising new sources of food waste?

- What constrains composters from expanding food waste composting?

- What qualities are urban and peri-urban farms and gardens looking for in compost?

- How do different mixes of food waste and other organic material affect compost quality?

- What types of compost are appropriate for different urban farm practices, products and existing conditions?

- How knowledgeable are urban farmers of the benefits of using different compost mixes?

- Would food waste generators favor greater recognition for their efforts to compost if it went to farms and gardens in food insecure communities?

- How might the plans of public agencies to divert food waste from landfills and develop green infrastructure boost the supply of affordable compost for urban agriculture?

- Could changes to existing city codes and regulations facilitate composting in the city?

- Could new composting facilities or transfer stations in the city lower transportation and handling costs?

We did not expect to answer any of these questions completely, but well enough to develop and actionable plan to expand the food-waste-to-compost system in the Milwaukee region while making more compost available for building soil in food insecure areas of the city. We expected that the questions might change somewhat as we proceeded, and more questions would arise.

Research activities to date have included:

- private interviews with key stakeholders;

- group meetings with stakeholders;

- surveys of urban, peri-urban and rural farmers and other compost users;

- analysis and mapping of primary and secondary data;

- review of policy documents;

- monitoring local events and public actions;

- conducting a "compost trial" on an urban farm with input from seven Farmer Advisors (including two that also produce compost commercially)

The first six bullets above involve standard qualitative research methods and were designed to answer Questions 1-4 and 9-12 above. The compost trials at Cream City Farms on the north side of Milwaukee were designed to help us answer Questions 5-8 above.

The research design for the compost trials were explained in detail in our proposal. We made some modest modifications to that approach, which are not able to document at this point in the project. The trials were run in 2016 and we have only begun to document the results.

Most of the research activities were conducted by students at UW-Madison and UW-Milwaukee. Three students were paid with SARE grant resources, and about 40 students contributed effort as part of their course studies.

Research results and discussion:

Following the new “progressive reporting” protocol of the SARE Program, this report is presented in three sections, which were written and submitted after each of the three years of the project ended.

2017 Annual Report

The meetings that we held with stakeholders during the proposal stage continued after we were funded and have provided substantial research value. These meetings combined private visits with individual stakeholders, subsets of similar stakeholders (including direct competitors), and “All Partner Meetings.” Once relationships became established, we used video conferencing more often and effectively to reduce travel time and costs for all involved.

One of our most important research contributors from the fall of 2016 to August 2017 was a UW-Madison graduate student, Tim Allen, who earned his master’s degree while conducting research under the guidance of his academic advisor, Dr. Stephen Ventura, and project coordinator Greg Lawless. Tim conducted multiple interviews with several key private sector actors in Milwaukee’s food-waste-to-compost supply chain, and the data he collected and presented in his thesis has been crucial to our subsequent modeling of that supply chain.

Meanwhile, a graduate student at UW-Milwaukee, Nicole Enders, assisted by Donna Genzmer, Director of the Cartography & GIS Center, utilized available data to generate maps and analysis of potential compost sites around the city of Milwaukee. Ender’s efforts were stymied somewhat by some unexpected limitations on data collection. We were only able to secure partial data that we requested from some of the commercial composters in the Milwaukee region, either because of competitive concerns or their lack of time to provide the data. For similar reasons we had difficulty collecting the locations of community gardens in the city and their compost requirements. Industry (NAICS) data that we expected to receive from a UW Extension partner but that exchange has been delayed for over a year because the partner has not received the data from his own source.

The primary and secondary data that Enders was able to collect enable her to complete senior project paper to earn her undergraduate degree in Biological Sciences, Geography, and GIS, which included maps large vacant lots in Milwaukee that would serve our project as hypothetical composting sites in the modeling and supply chain analysis led Dr. Anthony Ross of the Supply Chain Institute at by UW-Milwaukee. Ross also utilized data from Allen’s thesis and he collected additional and substantial data from Melissa Tashjian, owner of a small but growing compost hauling business serving the Milwaukee region called Compost Crusaders.

Ross and his colleague Mark Kosfield have been using the data to create scenarios and conduct sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of establishing new compost sites in areas around the city. They have produced a PowerPoint presentation of their results and a draft paper which currently inform our research and planning process and will eventually be made available to the public.

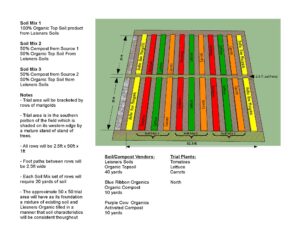

Two groups of students contributed to our compost trials at David Johnson farm. First, under the guidance of Dr. Julie Dawson of the Horticulture Dept at UW-Madison, twelve students conducted a greenhouse study of the our three selected compost products and measured germination and plant growth. While not conclusive, the process of running that study helped us design the outdoor trials.

The design of the outdoor trial is pictured below on the left, and a photo of its implementation appears on the right. Higher resolution images will be provided in the future.

We are still working on the results of the trials. Aside from whatever scientific conclusions we might make, the compost trials had several positive and intended impacts. One was that we build trust with the three competitive compost producers who supplied their product for the blind study. Second, we drew public attention to David’s farm and urban farming in general. Also, there is one bit of anecdotal evidence worth noting. Because of the isolated, multi-week drought that his the Milwaukee area last summer, and the breakdown of the watering system installed under David’s farm, much of his production for the year was lost. However, the plants grow in the compost beds above did considerably better. “The trial plots basically save my CSA farm this year,” he recently reported.

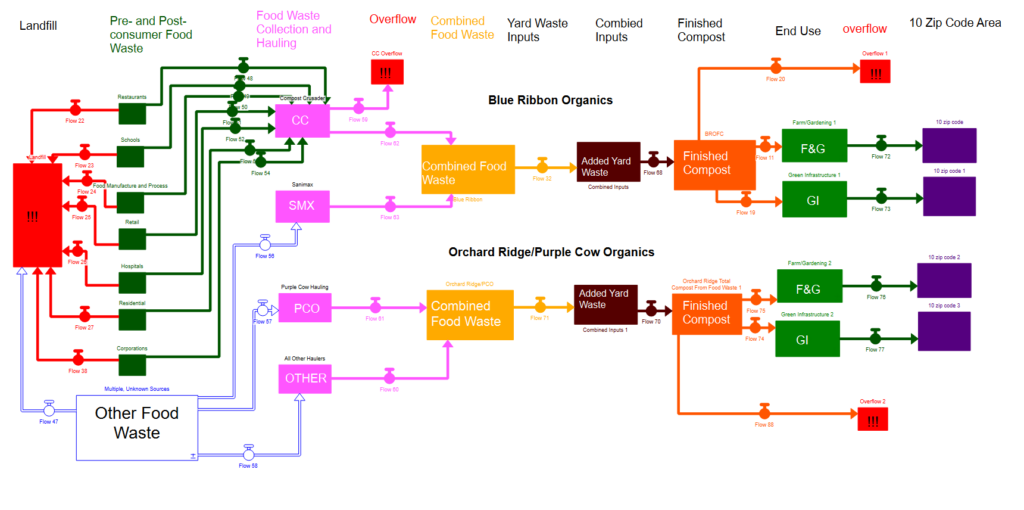

When graduate student Tim Allen graduated in August 2017 we used remaining funds for to hire another UW-Madison graduate student, Sheamus Johnson, to begin attempt to model Milwaukee’s food-waste-to-compost system using a software called Stella. This is a snapshot of that model from late 2017:

Diagram 1: A model of Milwaukee's food waste composting system

In 2018, we will continue integrating the results of all our research into creating a collaborative, multi-sector plan to ramp up Milwaukee’s food-waste-to-compost system.

Here are links to three student papers were completed in 2017 that provide some documentation of our research results to-date:

- Tim Allen’s master’s thesis, “THE STATE OF FOOD WASTE COMPOSTING IN GREATER MILWAUKEE: AN ILLUSTRATIVE CASE STUDY”, developed under the guidance of Dr. Stephen Ventura

- Joe App, Kelsey Busch, and Jessica Kanter’s, “Food Waste Composting for Urban Agriculture in Milwaukee”, developed under the guidance of Dr. Alfonso Morales

- Nicole Enders’ “Finding solutions for diverting food waste from landfills to compost: An urban, vacant lot assessment for the City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin” (link to be provided pending permission from author).

2018 Annual Report

2018 Report Sub-Sections

- Strategic Planning for The Growth of a System

- Data Collection Challenges

- Garden Team

- Compost Trials Team

- Farmer Network Team

- Green Infrastructure Team

- Supply Chain Modeling Team

- Circulating a Draft Strategy

- Joining a Statewide Network (Research Questions)

- Equity and Inclusion Goals

- Securing Public Sector Buy-In

STRATEGIC PLANNING FOR THE GROWTH OF A SYSTEM

In its essence, our SARE project is a multi-year exercise in strategic planning. While that practice is typically undertaken to help a single organization or business improve its outcomes, our strategic challenge is to develop a system involving multiple independent entities, including private businesses, non-profit organizations and public agencies that vary in size and maturity and are spread around the Metropolitan Milwaukee. Individuals representing these independent entities are stakeholders of the system. When they are engaged in the project and contribute to the strategic planning process, we have called them partners.

Many of the organizations our partners represent own and control segments of the system we are trying to develop. In that sense they are “proprietors” of the system components. A public agency owns the right to allocate tax dollars to purchase bins for a residential food waste collection pilot. A food waste hauler owns the trucks that empty the bins and hauls the contents to a property 13 miles south of Milwaukee that has been owned by the same family for six generations. There the food waste is combined with yard waste collected from multiple municipalities and converted over time into compost.

Small farms and gardening organizations purchase the system’s end-product and apply it to land they own or lease to produce food. When supported with public funds, homeowners can apply the compost to their lawns to fortify the turf so it absorbs stormwater more effectively, mitigating the discharge of raw sewage into public waterways.

Of course the system we are trying to grow is embedded in other interacting systems, including the natural environment, which mutually impact each other continuously. For example, when food waste is sent to a landfill, it emits significant quantities of methane gas before it is properly capped and the gas can be captured and utilized. The escaped gas is widely acknowledged as a major contributor to climate change, which has increased the frequency of severe weather events. In 2018, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) tied its record of six overflows of untreated wastewater, which also occurred in 1999. This happened despite a public investment of $1 billion to build a “deep tunnel” in 1994 under the sewerage district to capture more water.

Another example of complex interrelated systems involves the human, technical and natural resources that combine to feed 1.5 million people living in Metropolitan Milwaukee, a portion of whom rely on food pantries to sustain their diet. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EDA) uses an inverted pyramid to promote its “food recovery hierarchy” to prevent and divert wasted food. After its highest recommendation to reduce waste at the source, it urges us to redirect edible unused food to hungry people.

Our project focused attention on the EPA’s fifth advised action, processing food waste into compost. Furthermore, in our strategic planning to scale up the food waste composting system in Milwaukee, we made it a priority to ensure that a portion of the increased end-product would be made available and affordable to people living in 10 of the city’s 40 zip codes with the lowest average household income. For this reason we engaged several gardening organizations and urban farmers who grow food in those neighborhoods.

In summary, our shared goal as project partners is to scale up a multifold system of (a) separating inedible unused food from the waste stream, (b) combining that organic matter with yard residuals to produce compost, (c) growing markets for the increased end-product to cover the costs of hauling and processing, and (d) ensuring that some portion of the compost is made available and affordable in food insecure communities of Milwaukee.

The intended long-term outcomes include reduction of methane emissions from decomposing food in landfills, extended landfill lifespans, business expansion and job creation in food waste hauling and composting, and improved urban soil for food production and stormwater management.

To reiterate, the partners in this effort are independent entities who own and control different segments of the system we are trying to grow. There is no “boss” forcing us all to the planning table. A plan will emerge only if the respective parties agree to one.

DATA COLLECTION CHALLENGES

It is typical practice of strategic planning to gather a baseline of data about current operations before planning changes and improvements. For that reason we expended substantial resources in 2017 on research by University of Wisconsin students supervised by faculty and staff. We provided a brief overview of the research in our 2017 report above. To reiterate, our purpose was not traditional academic research, such as in testing an hypothesis, but rather to collect information that would inform a strategic planning process.

In March 2018 composter Sandy Syburg of Purple Cow Organics shared an important insight regarding the prospect of scaling up his segment of the system we hope to grow. Syburg said that most large composters like himself, who operate under the DNR’s 5,000 cubic yard permit for food waste, are going to maintain their system as close to that upper limit as possible. That means most will not expand in increments but rather in units of 5,000 cubic yards. To make that jump may require acquiring additional land and equipment, and they will only proceed if they are assured of having enough inputs to optimize the new site and enough markets to take the increased output.

Around that same time composter James Jutrzonka of Blue Ribbon Organics (BRO) explained that the DNR permit limit is for food waste held on the site at any given time. As Jutrzonka reported to project research assistant Tim Allen in 2017, he processed 7,736 cubic yards of compost in the prior year, from which he generated approximately 2,000 cubic yards of compost from food waste. From that we can calculate a 25.9% “conversion rate” from food waste to compost. More recently he estimated that he might be able to process as much as 12,500 cubic yards of food waste each year by converting it quickly into compost and selling it off his property. Achieving that “turnover rate” means his annual capacity could be 2.5 times his DNR permit limitation.

Allen, who was advised by project co-PI Dr. Stephen Ventura, also collected detailed information from Melissa Tashjian, owner of Compost Crusader (CC) a food waste hauling company based in St. Francis. She provided Allen with detailed data for all of 2015 and seven months of 2016, which broke out the food waste she collected from restaurants, schools, food manufacturers, food retailers, hospitals, corporate cafeterias and other miscellaneous suppliers. In 2015 she reported hauling a total of 428 cubic yards of organic waste, most of which was food. All of her product went to Blue Ribbon Organics in Caledonia, 13 miles from her current headquarters.

The detailed operational data from CC and BRO enables us to construct a partial model of the food waste composting system in Milwaukee. Unfortunately, so far we have been unable to collect updated supply chain data from them or any other partners, primarily due to project staff limitations.

We have also identified a number of specific challenges with regard to collecting data about the food-waste-to-compost supply chain. The include:

- Deciding on geographical boundaries (City, County, Metro)

- Getting same-year data from partners

- Converting weights to volumes and visa versa (lbs, tons, cu yds, gallons)

- Coping with “weight ranges” (food waste and compost per cubic yard)

- How to account for non-food in food waste (e.g. residential yard waste, paper towels, biodegradable plastic)

- Measuring food-waste-to-compost “conversion rates” given varying input proportions (food waste, yard residuals)

- Measuring food-waste-to-compost “turnover rates” which vary by system & season

- Factoring compost blends when quantifying demand (e.g. 50-50 compost-topsoil blend vs. 100% compost for new vs. mature garden beds)

- Incomplete data from stakeholder

The system we were trying to understand and expand is very broad in scope, and as we entered 2018 we felt it necessary to break up our group of approximately 25 active partners into teams to focus attention on segments of the system that interested them commercially and professionally. Most of our funding for student labor had been expended in 2017, and we were not able to arrange any further free support via coursework assignments. Any further need for would need to come from two paid project staff or from project partners, some of whom were provided honoraria at $100/hour for their time.

The teams we established in early 2018 reflected our need to analyze data collected by students in 2017, and to acquire remaining essential data. Meetings were held to ascertain the compost needs of three prominent Milwaukee gardening organizations; to analyze the results of the compost trials at Cream City Farms; to improve our understanding of urban and peri-urban farmers’ compost-related needs; to explore opportunities to utilize compost for stormwater management (green infrastructure), and to conduct supply chain analysis.

GARDEN TEAM

A “garden team” involving two prominent non-profits, Groundwork Milwaukee and Victory Garden Initiative, plus Milwaukee County Extension, estimated an aggregated need for 1,312 cubic yards of compost per year for community and backyard gardens they support.. Given time constraints, we were not able to determine how many individual gardens or people this total quantity would serve, or how much of it would go into neighborhoods considered food insecure. Nevertheless, the figure provided a useful measure from three organizations who were recruited as partners because of their long-standing reputation of service in the city and county of Milwaukee.

COMPOST TRIALS TEAM

The “compost trials team” concluded with some regret that the results of our 2017 experiment on an urban farm in the heart of a food insecure neighborhood were largely inconclusive. While soil samples were taken from the plots as well as high resolution images of plant growth taken in intervals through the season, our project requested insufficient to analyze the data comparing three local compost products in a timely manner and draw useful conclusions.

The trials were also set up as a means of attracting area farmers to one or more field days, to allow them to observe and compare the compost products themselves, while enabling our team to assess their knowledge of compost attributes. A couple of informal visits were arranged, involving most of the seven farmers directly associated with the project. However, our two attempts to organize public field days to attract more farmers were cancelled. In the fall of 2017 our Milwaukee-based project staff determined that the farm site was not presentable due to weed issues. In the fall of 2018 we offered project funds to hire young people from the community to help with weeding, but due to insufficient pre-registrations and competing events we decided to cancel the second field day.

Nevertheless, the compost trials of 2017 did produce some real value. As mentioned in our 2017 report, David Johnson who farms on the site reported anecdotally that his crops grown in the compost trials fared considerably better through a period of drought than those in the rest of his field. Better enough, he said at the time, to “save my CSA farm this year.”

Furthermore, while Johnson farms the site, it is actually owned by the City of Milwaukee, and substantial investments were made by the City, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District and other entities to make it a model for stormwater management. The City leases the land to one of the gardening organizations mentioned above, which subleases is to Johnson. Our project had to engage with this confluence of public and private partners, purchase compost from three competing partners, while also coordinating contributions of students and faculty from two universities.

It may still be possible in 2019 to leverage the relationships formed through these interactions to showcase the property and the use of compost for both food production and stormwater management.

FARMER NETWORK TEAM

Partly because of our failure to attract area farmers to the compost trials in 2017, we developed a new plan in 2018 to invite farmers from the region to attend six monthly educational events, specially designed for urban and peri-urban vegetable growers. Our hope was to re-establish a network of such farmers that had dissipated a few years earlier due to insufficient coordination, and to tap the revitalized network to gain a better understanding of local farmers’ needs related to compost.

One planning meeting and two educational workshops were held and well attended. The workshop in May 2018 featured a seasoned CSA farmer who spoke to the apparent decline of that movement. A video recording of her presentation on our project’s YouTube playlist has had 173 views to date. While her talk was not about compost, the turnout showed promise for the reinvigoration of a farmer network in SE Wisconsin. Unfortunately, the project staff person responsible for this team was unable to organize additional workshops, because he left the project for another job in August.

Another farm-related development was the dissolution of Growing Power in November 2017. Their founder and CEO, Will Allen, was originally a major partner in our SARE project, and a passionate advocate for the role of compost in urban agriculture. At the start of our project, we hoped to tap Allen’s connections to the Mayor’s office and other public agencies to raise awareness of our efforts.

As one of the country’s most prominent representatives of urban agriculture, the demise of Growing Power may bolster those who have questioned the real potential of growing food commercially within cities.

In a survey of farmers that we circulated before and after the start of our project, we tried to determine demand for compost among farmers in Southeastern Wisconsin. Only 22 farmers have completed the survey to date. Most demonstrated good knowledge of the value of compost for growing food. However, in aggregate these 22 farms represented a modest demand for compost: only 308 cubic yards per year, or less than a quarter the demand from our three Milwaukee gardening organizations.

It is also worth noting that both farmers and garden program managers said it is cost that inhibits them from purchasing as much compost as they would like to use each year. That may explain why some farmers, including Will Allen, are turning to cover cropping and green manure to achieve some of the same benefits that compost provides.

We will continue to invite our original farmer advisors to participate in “All Partner” meetings in 2019. We hope to include provisions in our strategic plan that address their compost needs and cost concerns–especially for those located in food insecure neighborhoods of Milwaukee.

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE TEAM

Even prior to the start of our project, while writing our pre-proposal in the early fall if 2015, we recognized that sales of compost to gardening programs and local farmers might be insufficient to cover the costs of hauling and composting a significant quantity of Milwaukee’s food waste. In 2018 it became clear that the best prospect for fully utilizing an increase in compost production is to incorporate it as a soil amendment to absorb stormwater, which is one of several forms of green infrastructure (GI).

In February 2018 we convened a small team of project members to explore the possibility of utilizing composted food waste as component of a holistic GI strategy. One year earlier, several project partners toured the facilities of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD). After the tour MMSD representative Jeff Spence speculated that his agency might be interested in testing the ability of residential yards, fortified with compost, to hinder the runoff of rainwater into storm sewers during heavy rain events. He suggested an area of the city where there was a new public program to remove downspouts that ran directly into the sewer system.

After more meetings, many emails, and a substantial investment in project staff time, we were able to jointly support a pilot project in the 53212 zip code. In September 2018, 33 households received approximately 3 cubic yards of compost from Blue Ribbon Organics, plus aeration and grass seed, in exchange for a promise to care for the lawn after the application. A third party not originally involved in our project, Natural Solutions of nearby Menomonee Falls, aerated the lawns and spread the compost and seed. In aggregate the households received 101 cubic yards of compost, covering 65,637 square feet with approximately half inch depth. The total cost, paid for by MMSD, was $5,050, which is $153 per household and $50 per cubic yard of compost applied.

The results of the GI pilot on turf improvement will not be known until early summer 2019, and it is unlikely that measurements of stormwater absorption will be taken. But the value of the initiative, which was supported substantially by SARE-funded staff, was in strengthening our relationship with MMSD and elevating the prospect of using compost as a major component of stormwater management strategies.

The potential demand is substantial. In a major report from 2013, MMSD projected to spend nearly $1.3 billion on GI by 2035. As explained above, their motivation is that extreme weather events can overflow their water treatment capacity and force substantial discharge of raw sewage into basements, rivers and Lake Michigan, which pose a serious threat to public health while also causing major property damage.

Their $1.3 billion spending forecast was spread over 22 years. The portion to be spent specifically on soil amendments was $1.045 million per year. If all of that was used to purchase compost, it would buy 20,900 cubic yards, based on an estimated cost of $50 per cubic yard for delivery, spreading, turf aeration, and grass seed.

To summarize the demand estimates made above, we found that three prominent gardening organizations would like to utilize 1,312 cubic yards of compost each year that 22 area farmers would purchase 308 cubic yards each year, and that MMSD might purchase as much as 20,900 cubic yards every year through 2035.

While public agencies are not beholden to honor the projections of their long-term plans, the size of the MMDS projection is striking. We hope our decision to invest some SARE resources to spark some movement in that direction will prove worthwhile.

Furthermore, MMSD’s Jeff Spence indicated that when GI investments are made to properties adjacent to urban gardens and farms, the compost could be spread generously to support food production and stormwater management. In other words, MMSD’s investment in GI could subsidize soil improvements for farms and gardens in food insecure communities.

SUPPLY CHAIN MODELING TEAM

Beginning in January 2018 and throughout the year, faculty and staff from UW-Milwaukee and UW-Madison met with a small group of individuals who owned private businesses in the food-waste-to-compost supply chain, namely haulers and composters. The most consistent attendees from the latter group were Melissa Tashjian of Compost Crusader and James Jutrzonka from Blue Ribbon Organics. From the start of the project Tashjian and Jutrzonka were very willing to share data from their hauling and composting operations, respectively, and it was primarily their data that allowed us to begin modeling and analyzing the supply chain.

Project partners Dr. Anthony Ross and Mark Kosfeld from the UW-Milwaukee’s Supply Chain Management Institute (SSMI) presented drafts of their supply chain analysis in January and March. Their final presentation will be attached to our 2018 report. Their analysis utilized real data from Tashjian on food waste quantities coming from 33 locations in and around Milwaukee, and transportation costs. With that data, they ran scenarios for different headquarter locations for Compost Crusader as well as eight different hypothetical composting sites within the city of Milwaukee.

Currently Tashjian’s trucks and office are located in St. Francis, just outside the southern border of Milwaukee, and she hauls 100% of her collected food waste to Blue Ribbon Organics, 13 miles south in Caledonia. The SSMI analysis found that Tashjian’s overall costs could be reduced significantly by relocating her HQ to locations closer to certain hypothetical composting locations.

SSMI also ran scenarios for increasing food waste origin volumes. This was important because our project’s goal is to scale up the volume of food waste diverted from landfills to composting. Under a scenario of quadrupling volumes, the optimal destinations to the hypothetical composting sites in the city only changed marginally, while the capacity at Blue Ribbon Organics was exceeded.

An important limitation on the value of this analysis is that several project stakeholders who have been actively looking for sites to compost in the city have not been able to acquire any. After the 2008 economic recession, many properties in Milwaukee went into foreclosure and the city took ownership. As the economy has improved, it is much harder to locate affordable land for composting, even if it does satisfy the requirements of the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) for set-backs from waterways and city zoning restrictions. Blue Ribbon Organic operates on 14 acres in a rural area south of Milwaukee. Those looking for just one acre in the city for composting have found nothing during the 2.5 years since our project started. If new composting facilities that accept food waste do become available, most likely they will be located outside the city of Milwaukee.

However, it is possible Tashjian could relocate her HQ. Another less disruptive option is for the City and DNR to authorize transfer stations in optimal locations for Compost Crusaders and other haulers to aggregate food waste for transportation out of the city. Serious analysis of this option has not been undertaken yet.

Another aspect of our supply chain analysis in early 2018 involved developing a “stock and flow” model using a software called Stella to examine how increases in the input of food waste would impact the current capacity of processors. We were able to tap remaining dollars to pay graduate student Sheamus Johnson to take data that former student Tim Allen collected from Tashjian, Jutrzonka and another composter, Sandy Sieburg of Purple Cow Organics.

The model was useful in two respects. It was able to provide a simple illustration of what happens in a throughput system when inputs are increased and capacity is exceeded. A related benefit is that it demonstrates the value of sharing system-wide data. We made a short video about the development of the Stella model to demonstrate the value of the effort.

During the first quarter of 2018 our project also had an opportunity to connect with another similar research project at UW-Madison. Dr. Victor Zavala of the Scalable Systems Laboratory, Dr. Rebecca Larson of the Biological Systems Engineering Department, and their colleagues are developing optimization models and solution algorithms to identify new efficient pathways to recover valuable products from agricultural livestock waste and other waste streams. We gave Larson access to all of our data folders, but the quality and completeness of our system data is unfortunately lacking.

While our staff resources to collect additional supply chain data were severely limited, we did make an attempt to circulate a survey tool using Qualtrics to gather critical data from haulers and composters. Our efforts were frustrated when some partners were reluctant to share operational data, either because they felt it would compromise them competitively, or they did not have time, or they did not see the value in sharing the data. The prospect of only gathering partial data for the system was discouraging, and we suspended our efforts at supply chain data collection. Another factor was that the project had expended the last of its student dollars, and we were short on staff to enter new data into our Stella model.

Originally we expected that GIS mapping would be an important component of our supply chain analysis work. It did prove useful in that the work of UW-Milwaukee undergraduate Nicole Enders, under the supervision of Co-Principal Investigator Donna Genzmer, provided Ross and Kosfeld with real locations of unutilized City-owned land for analyzing transportation costs under various scenarios. However, much of our best data was acquired after Enders completed her degree.

For example, we were promised access to industry data (NAICS) from a UW Extension colleague that would have allowed Enders to map densities of potential food waste sources. While that raw data for Milwaukee was never acquired, in July 2018 the EPA released an outstanding resource, the Excess Food Opportunities Map, which provides food waste estimates for all companies across a range of industry segments (restaurants, retailers, schools, hospitals, etc.) Unfortunately, this valuable data arrived after Enders had graduated and our funds for student mapping were expended.

At the close of 2018, the difficulty of collecting sufficient data on an annual basis from private sector partners was an obstacle to meaningful strategic planning. But it was not the only obstacle.

CIRCULATING A DRAFT STRATEGY

The update above spans much of 2018 and includes on-going efforts to collect critical data from “proprietors” of different components of the system we are collectively trying to grow. A quarter into the year, despite lacking sufficient data for reliable planning, we began to circulate elements of a plan. Back in the summer of 2017, as Tim Allen was completing his master’s thesis, we asked him to generate a list of recommendations related to growing the system. At that point, thanks to his interviews with many partners and stakeholders, we felt Allen had a sufficient overview of the entire system to understand some of the essential necessary steps to growing it.

In March 2018 we presented an “8-Point Plan” to all project partners that were developed from Allen’s original recommendations. Partners had a brief period of time to provide feedback on the rough outline before it was presented as a poster at the SARE National Conference in St. Louis. We made a more concerted effort to collect their feedback though a series of three video-conference meetings in the summer. The meetings were fairly well attended, though participation from public agency partners was somewhat lacking, and we did not make substantial progress on fleshing out the plan.

By mid-summer 2018 the planning process had grown stagnant. A few partners, namely Tashjian of Compost Crusaders and Jutrzonka of Blue Ribbon Organics, were always ready to contribute time and energy to the project. Both relatively small businesses, they have both made a considerable investment in food waste hauling and composting, respectively, and it may be fair to say they have the most to gain from a plan to scale up the system.

JOINING A STATEWIDE NETWORK (RESEARCH QUESTIONS)

One of the recommendations that surfaced in the summer video-conference meetings was that Wisconsin should form a state chapter of the US Composting Council. To learn more we reached out to the primary leader of the Minnesota chapter, Ginny Black, and we arranged a video-conference with her for July 26. Knowing that Milwaukee would need other composting activists from around the state to join an effort to form a Wisconsin chapter, we invited individuals who we knew.

As can be said of many large American cities, Milwaukee is somewhat disconnected from the rest of the state in many respects, far beyond the world of composting. Nevertheless we were able to entice about 20 individuals to join the video meeting with Black from Minnesota. The group concluded in subsequent email communications that it may not be necessary at this time to form a Wisconsin chapter of USCC, but instead Milwaukeeans were encouraged to get more involved in some networks and associations that were already meeting regularly across the state.

To continue the attempt to connect advocates statewide, in July 2018 SARE project staff travelled to UW-Stevens Point in north central Wisconsin, where it was reported that both the university and private efforts were underway to scale up food waste composting. Also, 1-on-1 visit was arranged with a long-time composting advocate, Meleesa Johnson, Director of the Marathon County Solid Waste Department, located north of Stevens Point. These visits and intermittent emails involving about a dozen public and private sector composting advocates led to another statewide video-conference in late November that was focused on pressing research questions that were common across the state. Many of our SARE project faculty partners participated in this meeting. The 90-minute conversation spanned many research topics, including:

- The compostability of compostable packaging–best practices in the Wisconsin climate

- Practical steps to get more municipal yard waste to accept food waste

- Best recipes and practices to utilize compost cost-effectively for stormwater absorption for different soil types (e.g. compacted clay soil in Milwaukee)

- Learning what municipalities needs are regarding food waste composting

- Review of current public policy in other states

- Are micro-impurities (chemicals, pharmaceuticals) a concern with compost

- Revisiting the prospect of using compost for green infrastructure the Wisconsin Department of Transportation

- How develop markets for products coming out of the composing process

- Most cost effective way of connecting community goals and end user needs

- Public education needs on compost – how to create an educated populace

- Best in-vessel composting systems

- How in-vessel compare to digesters

- Citywide collection logistics for a city the size of Ashland – especially curbside

- Big picture look at what kinds of processing communities need to achieve their desired ends. Working on an optimization model to that end. Drivers are finances, price points, markets, city needs like green infrastructure, reducing phosphorus, etc.

The point was made that there has been plenty of research on many of these topics, and Dr. Rob Michitsch at UW-Stevens Point shared the following sources:

- USCC: https://compostingcouncil.org/factsheets-and-free-reports/

- USCC Industry Publications: https://compostingcouncil.org/publication-resources/

- CCREF Toolkits: https://www.compostfoundation.org/toolkits-resources

- CCREF Publications: https://www.compostfoundation.org/Education/Publications

- BioCycle Magazine: https://www.biocycle.net/

- Journal of Environmental Quality: https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/jeq

- Compost Science and Utilization: https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/ucsu20/current

- The Composting Collaborative: https://www.compostingcollaborative.org/resources/

By the end of 2019 our SARE project had added 25 “statewide” names and email addresses to our original Milwaukee-area contact sheet of 40 partners. In 2019 we will continue to explore prospects for and practical steps to strengthening the connection between food waste composting in Metro Milwaukee and the rest of the state.

EQUITY AND INCLUSION GOALS

From the beginning our project embraced goals of equity and inclusion. Our strategic goal of scaling up the food waste composting system in Milwaukee included a priority to make high quality compost available and affordable to improve soil for food production in sections of the city that are food insecure. We also intentionally developed a team of project partners that is diverse in race, gender and socio-economic status. We also chose a site for our compost trials in a neighborhood on the city’s North Side that is 49% African American and where 35% of residents live below the federal poverty level.

Several efforts were made in the course of the project to adhere to these goals. We made repeated attempts to locate an acre of land for an African American entrepreneur and partner to realise his plans for a composting facility in the city. Unfortunately, none has been found to date. We held a public workshop on composting at the former location of Growing Power on the far North Side.

When implementing the green infrastructure pilot in the 53212, we found that the initial group of 20 households that signed up for free compost were located in the eastern half of the zip code (Riverwest), which is predominantly white. They were all participants in the City’s residential food waste collection pilot and reachable via email. Unhappy with the geographical distribution, we delayed implementation, produced promotional door hangers, and paid youth working for gardening program partner to distribute them in the western half of 53212 (Harambee). As a result of the effort, we were able to recruit 13 households from that neighborhood.

For our SARE project’s dedication to working with community-based partners to develop a food waste composting strategy that benefits all city residents, in July 2018 we received a Community Partnership Award from UW-Madison Chancellor Rebecca Blank.

Equity and inclusion are priorities for Milwaukee public agencies as well. We recently learned that it plays an important factor in whether and how the City’s Department of Public Works (DPW) will expand its small residential food waste collection pilot, which currently involves 500 homes in the predominantly white and relatively affluent neighborhoods of Riverwest and Bay View. In the pilot, households must pay $12 per month for the service, which occurs weekly in warmer months and biweekly in the winter. Further expansion of the pilot cannot occur with DPW support unless provisions can be made to include a more diverse population and accommodate those of restricted economic means.

SECURING PUBLIC AGENCY BUY-IN

Our project was originally supposed to end on September 30, 2018. However, we requested a 6-month no-cost extension (and later another) because we had not accomplished our primary goal of getting project partners to agree to a plan to scale up food waste composting in and around Milwaukee. In October we circulated a version of a plan that built on the 8-Point Plan that was first revealed back in March. We recruited partners to take roles in presenting the new draft at a video-conference originating from UW-Milwaukee campus on October 25, 2018. The event was pitched as a “practice run” for formal presentation of plan to a public audience in early 2019.

While the practice-run went well and produced a lively discussion among those who attended, it had become all too apparent that an important subset of partners was insufficiently engaged: the relevant public agencies, particularly DPW and City’s the Environmental Collaboration Office (ECO), and the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD).

It was a promising sign in the final two months of 2018 when Tim McCollow of ECO was able to give more time providing leadership in the project. In a series of video-conference meeting, he, Tashjian of Compost Crusaders and project PI Greg Lawless of UW Extension met to discuss a public awareness campaign and other details of our draft strategic plan. In late December Lawless injected a touch of humor into personalized holiday video messages he sent to about 20 key partners, in hopes of persuading them to help complete a meaningful plan in 2019.

2019 Annual & Concluding Report

Thanks to the “progressive” reporting system that was recently adopted by SARE this final section will simply summarize the results of meetings and a major obstacle that arose in 2019, and then make some summary comments on the overall project effort from 2016-2019.

As we entered 2019 it was apparent that a meaningful plan to scale up Milwaukee’s food waste composting system would not materialize without getting critical decision-makers at several key public agencies at the table together. These included the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD), the city’s Department of Public Works (DPW), and their Environmental Collaboration Office (ECO).

DPW is the city’s third largest agency after police and firefighters. They are responsible for paving streets and fixing bridges, managing city-owned water mains and sewers, fire hydrants and trees along city streets, and they also provide garbage and recycling collection.

From early on, we saw DPW as a critical agency of the residential food waste collection pilot they launched in 2017, about six months after our project began. Their pilot involved 500 households in two neighborhoods, Riverwest and Bayview, where residents are predominately white and have a reputation of supporting environmental causes.

Because of their pilot project, we saw DPW playing an important role in the supply side of our system, by facilitating the provision of food waste for composting. They contracted with Melissa Tashjian of Compost Crusaders, who picks up the residential food waste weekly much of the year and bi-weekly in winter. She delivers that product plus food waste from her commercial and institutional clients to James Jutrzonka of Blue Ribbon Organics, about 20 miles south of Milwaukee in northern Racine County. The residents pay $12 a month for the service, most of which goes to cover Tashjian’s costs, and she in turn pays Jutrzonka a tipping fee to take the food waste.

At the start of our project, a staff person from DPW joined our meetings as agency representative, but she left for another job and her position was not re-filled for more than a year. In the spring of 2019, our goal was to get Rick Meyers, their Sanitation Services Manager, to attend and speak to their future plans. The 500 pilot homes represent less than 3% of the city’s population. Tashjian, of all our project partners, was most interested in expanding the residential pick-up pilot substantially over time. Jutrzonka was willing to accept more food waste as long as it was not contaminated with non-compostable materials, and didn’t exceed his processing capacity.

MMSD is a state-chartered government agency that provides waste water services to 28 municipalities in the greater Milwaukee region. Since 1925 MMSD has led the nation on a number fronts, including the use of an activated sludge sanitary wastewater treatment process to create a marketable fertilizer under the brand name, Milorganite. In 2017 they sold more than 45,000 tons of the product to 41 states, Canada and Hong Kong, generating $10.3 million in revenue. Our project’s contact, Jeff Spence, has had responsibility for Milorganite sales, and he currently now serves as Division Director for Community Outreach and Business Engagement. We also hoped to engage another staffer at MMSD, Karen Sands, Division Director for Planning, Research and Sustainability.

One of MMSD’s major challenges is to manage stormwater during severe weather events that can overwhelm its capacity capture and treat all of the water that flows into its system. The threat is most acute in the portion of the system that combines stormwater and sewage into a single system, most of which is located in the City of Milwaukee. When stormwater exceeds the system’s capacity, the district is forced to dump excess contaminated water into Milwaukee’s three rivers, which flow directly into Lake Michigan. This is a major environmental, economic and public health threat. In fact, this is a challenge for both the city and district, and they work closely together to mitigate the risk.

MMSD is currently operating under a plan that was released in 2013 called the Regional Green Infrastructure Plan. Its goal, as restated recently by Spence, is to capture (divert and infiltrate) 740 million gallons each time it rains by the year 2035, through a wide variety of green infrastructure practices. The total cost to achieve this goal was estimated at $1.3 billion. Of that, they projected to spend $46 million on “soil amendments,” which is the application of compost, well-rotted leaves, and other natural materials, as a top-dressing over established lawns to improve soil tilth and support a thicker lawn and more absorbent soil that can soak up stormwater and reduce runoff into the combined sewer system. Over the 22 years of the regional plan (2013-2035), MMSD said the $46 million would be split roughly evenly between itself and the private sector. We have interpreted that to mean that MMSD was planning to spend $1 million on soil amendments on average each year.

As described in our 2018 Annual Report above, our project implemented a small green infrastructure pilot last fall in partnership with MMSD. The 33 homes in the 53212 zip code that received about a yard of free compost from Blue Ribbon Organics, who partnered with another firm, Natural Solutions of nearby Menomonee Falls. The total cost of $5,050, or about $153 per home, was covered by MMSD. The application by Natural Solutions began with lawn aeration, and then compost was then blown onto the lawns with a mixture of grass seed.

Because of MMSD’s support of this pilot and the $1 million per year commitment they made to soil amendments, we believed they represented a significant potential impact on the demand side of our food-waste-to-composting system. At the meeting on March 14, 2019, we hoped to get their commitment to ramp up their purchase of compost from area processors. In a scenario we introduced two months later, we estimated that $1 million per year would purchase 20,909 cu yds of compost. This would be a very significant increase over the volume of composted food waste that is currently being sold and utilized in the Milwaukee area.

The third agency we invited to the March 14 meeting was the Environmental Collaboration Office. ECO unit is located in City Hall and supports Mayor Tom Barrett’s strong public commitment to environmental sustainability. Throughout the SARE project we had consistent participation from Tim McCollow, who runs an award-winning program called HOMEGR/OWN, which promotes food production throughout the city as well as green space developments by re-purposing city-owned vacant lots. Our goal in 2019 was to get McCollow’s boss, ECO Director Erick Shambarger, more engaged in the final phase of the planning process. While the HOMEGR/OWN program is a significant buyer of compost, we were hoping to get Shambarger’s approval to expand their role in educating Milwaukee residents about food waste composting options.

On March 14 we were able to pull all of these individuals, with the exception of Karen Sands, into a meeting at the Global Water Center in Milwaukee. We presented two images, shown below. The first we had been using for six months to show the food-waste-to-compost system in its simplest form. It shows the supply of food waste flowing to commercial composters who process it and sell it into markets that utilize it.

The second image was developed specifically for this meeting, to show where we saw each agency and business fitting into the emerging plan to grow the system. In this case, we split the demand component into two separate parts, “green infrastructure” and “farms & gardens,” because growing them required very different strategies and contributors. We indicated our expectation that many more partners would also play a role if these agencies and businesses all got behind a plan to expand the city’s system of food waste composting.

Simplified Supply Chain Image

Supply Chain Featuring Critical Actors for Plan Implementation

The goal of the March 14 was to get each of these critical actors to speak to their interest and ability to scale up their respective portion of the system. We presented specific action items associated with each system component. These specifics were developed from the outline of an 8-Point Plan that our project first presented a year earlier. The two project partners who were most involved in developing the goals and actions in the table below were McCollow from ECO and Tashjian from Compost Crusader.

| System Components |

Proposed Goals & Actions |

|

Food Waste Diversion |

|

|

Food Waste Composting |

|

|

Compost for Green Infrastructure |

|

|

Compost for Urban Farms & Gardens |

|

Table 1: An outline of goals and actions that were proposed to city and regional agencies in March 2019

Two of the three public agency representatives were hesitant to commit to these goals and actions under the time frame we presented, which was to begin small steps in 2019 and spend the next six months planning larger steps over the next four years. Rick Myers of DPW explained that, while the city had made a goal to divert 40% of waste from landfills by 2020, it was falling well short of that goal. The reason, he said, was that the city council had not approved sufficient budget authority to carry out the investments and measure necessary to meet the goal. The main upfront cost to the city for expanding the pilot was the purchase of the $50 “bins” that each participating household receives in addition to their garbage and recycling bins. Of course, there are also staff costs associated with initiating, managing and monitoring the arrangement with each new household.

Quite simply, the city had other priorities. Our hope to significantly expand the residential food waste pickup was not going to happen anytime soon. DPW was committed to maintaining the service for the 500 households. McCollow from ECO reported that it was contributing some of its agency funds to help expand that pilot to 700 homes in 2019, but that would be the extent of the expansion.

In a subsequent phone conversation with Myers and his new staff member, Samantha Longshore, we learned that another obstacle for the city to expand its pilot was that that expansion must be “equitable.” That meant that if significantly more homes would be added, they needed to be located in parts of the city that were less white and affluent. This is an important public stance for elected officials and agencies in a highly segregated city with enormous racial inequities.

That said, Meyers and Longshore did concede that if Tashjian wanted to take it upon herself to recruit new homes, purchase the bins, collect the monthly $12 service fee, and carry out the service, as a private business she could do so. That seems to present a potential strategy for expanding the supply of food waste to the system our project had set out to scale up. However, as small business owner, Tashjian’s ability take on the expansion of residential food waste collection would seem to be constrained currently by insufficient capital resources.

The forthright response from DPW’s Meyers at the March 14 meeting that his department could not expand the supply of food waste in the near future was a blow to the plan we were proposing. A second blow came from Spence at MMSD, in response to our question as to whether his agency was prepared to significantly scale up the purchase of compost as a soil amendment to mitigate the risk of stormwater damage. In his response he repeated past concerns that it was still not clear if the application of compost as a top-dressing effectively improved soil tilth to absorb heavy rains.

We asked if MMSD could fund research to test the effects of the pilot we ran with 33 homes in 53212, but at the March 14 meeting and in the months since, we have not received any indication from Spence or his colleague Karen Sands that MMSD was prepared to make such investments in expanding compost applications or conducting research. That does not mean that the agency is not internally planning to do so. However, their inability to make any commitments as partner in our SARE project represented a second major setback to our hope to finalize a meaningful plan by the project’s termination on September 30, 2019.

Fortunately, there was one very bright outcome of the meeting on March 14. Shambarger, Director of ECO, announced that the Milwaukee City Council had recently approved spending $2.8 million on green infrastructure in the city to address the stormwater issue. This was very surprising and welcome news for our project, as it allowed us to see real potential to scale up the system immediately. It seems that Shambarger has the full authority to purchase compost for that purpose in 2019, and he only needed more clarity on specifications for the compost including product quality and application methods. The meeting ended on a high note.

Jutrzonka, Lawless and Tashjian all smiles after the meeting on March 14, 2019

In the two months that followed, SARE Project Manager Greg Lawless went back and reviewed some of the essential data our project had collected, dating back to the initial research of graduate student Tim Allen and including additional data collected in 2018 as well as the recent approval of $2.8 million for green infrastructure spending in Milwaukee. He first presented this assembled information at a Zoom video conference on June 10 that was described as the project’s penultimate meeting. The table below is an updated version of that data presentation. The notes immediately below the table explain the sources and rationale for the data where indicated parenthetically.

In our 2018 Annual Report we discussed the significant difficulties we encountered in collecting data to help us understand and characterize the system we were trying to expand. The table and notes below involve numerous rough estimates and extrapolations from data that represent only a very partial picture of the current system. It is very likely that a better funded and more robust research effort would paint a substantially different picture. That said, we feel confident that several points that arise from our data analysis and presentation would hold true.

First, it seems clear that a very small percentage of the food waste produced in Milwaukee and the surrounding area is currently being diverted from landfills into commercial composting. Second, there appears to be some room in the processing capacity of one major composter to accept more food waste, assuming he can maintain his optimal turnover rate, but the dependence on only one operator would seem to put the entire system at risk. Moreover, as previously noted, hauling to and from a composting facility is a considerable expense. Third, the green infrastructure strategies that are incorporated into the plans of two large agencies serving the Milwaukee area represent very substantial potential demand for compost.

This latter point is the most significant finding of our project. As we have said, our project has aimed to expand a throughput system. The pull of increased demand for compost for green infrastructure could motivate the current system’s primary composter of food waste to expand his capacity, and it could possibly also persuade other composters to accept food waste and expand their capacity. If Tashjian of Compost Crusaders knows for certain that she has a place to deliver food waste, she is confident she could expand her collection from commercial clients, even if the city is currently reluctant to expand the residential collection pilot.

After the penultimate project meeting on June 10, Lawless reached out to Shambarger and asked if there was any way that $3,000 in remaining grant funds could be used to facilitate the utilization of food waste made from compost for their $2.8 million green infrastructure strategy. Shambarger said yes, if you could fund the development of the specifications for the compost. He had a consultant in mind, Kristin Shultheis, a soil scientist with Oneida Total Integrated Enterprises (OTIE), an engineering and construction services company owned by the Oneida Nation. It would have seemed that a major project breakthrough was in the works. We may not have achieved the complete plan that we had aimed for but the project could honestly claim to have pulled some of the key players together to advance a major expansion of the system over the course of three years.

Unfortunately, one more obstacle arose over the course of the late spring and summer that none of us foresaw. It involves a set of chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, that are a common component of compostable bowls and plates. Research is incomplete on whether this represents a public health concern from compost that includes these products, but it has become an obstacle in public acceptance. It’s looking like it will result in at least a temporary reversal in the expansion of the system, a retraction of the diversion of food waste from landfills to compost.

| POTENTIAL SUPPLY | MAXIMUM CAPACITY | POTENTIAL DEMAND |

|

City: 46,618 tons/yr (1) ÷ .366 (2) County: 74,552 tons/yr ÷ .366 |

# of food waste composting facilities: 1 (BRO) |

Farmer survey: 308 cu yds (4) |

| ACTUAL SUPPLY | ACTUAL PROCESSING | ACTUAL DEMAND |

|

Milw County food waste collected (CC 2018): 966 tons ÷ .366 = 2,639 cu yds 1.3% of county food waste |

7,736 cu yds of food waste (BRO 2016) (8) 62% of the maximum capacity |

2,000 cu yds of compost (BRO 2016) represents a 25.9% conversion rate (9) |

| SCENARIO: Divert 8% of county food waste, or 16,296 cu yds | 16,296 cu yds of food waste processed | 4,221 cu yds of compost produced to be utilized |

Table 2: System Data with 8% Scenario

Table Notes:

(1) This and the county figure were extrapolated from a statewide estimate of 455,259 tons. Source: 2009 Wisconsin State-Wide Waste Characterization Study prepared for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR).

(2) Food waste weight by volume depends on moisture content. This figure is the midpoint of 9 estimates assembled in Volume-to-Weight Conversion Factors, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery April 2016.

(3) Blue Ribbon Organics (BRO) operates under a WDNR permit that allows 5,000 cu yd of food waste on the property at any given time. By converting it to compost and selling it off to customers, he claims he can handle 12,500 cu yds per year, which we describe as a 2.5 turnover rate.

(4) Our projected circulated a survey to small fruit and vegetable farmers in 2016 and again in 2017. Most of the 22 respondents were in SE Wisconsin. We acknowledge that this small sample likely underestimates demand for compost from farmers in the region.

(5) Based a joint interview with 3 large gardening organizations in Milwaukee. Jutrzonka of BRO was not willing to share his private customer data, so this table does not include sales to garden centers, homeowners, or commercial landscapers. We only know that he has, up until now, always sold all of his finished product.

(6) Based on MMSD’s Regional Green Infrastructure Plan of June 2013, which projected $1.3 billion in spending on GI by 2035 (22 years), “roughly split between the public and private sectors." Of that, $46 million (3.5%) would be spent on soil amendments, or $2.09M annually. MMSD’s share of that expenditure (50%) would utilize 20,909 cu yds of compost, based on our pilot project cost of $50/cu yd.

(7) Using the MMSD portion of their GI budget spent on soil amendments (3.5%), we estimate the city will spend $99,077 of its $2.8M annual GI budget on compost, which would buy 1,982 cu yds at $50 per.

(8) This data was collected by Tim Allen for his Master's Thesis from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2017. We acknowledge the 2-year mismatch between CC’s food waste supply data and BRO’s processing volume. His higher volume reflects the fact that he receives food waste from other haulers apart from CC who were not part of our study.

(9) The process of composting reduces the weight and volume of food waste through moisture reduction and the breakdown of materials. It should be noted that BRO adds municipal yard waste to food waste at roughly 3 to 1 ratio. To confirm what we are calling a “conversion rate” would require further analysis. One article to consult is Calculating the Reduction in Material Mass And Volume during Composting Gary A. Breitenbeck & David Schellinger, published in the Journal of Compost Science & Utilization.

The Discovery of PFAS in Biodegradable Food Service Materials

On May 30, 2019 an article appeared in the magazine Popular Science with the headline, “Eco-friendly packaging could be poisoning our compost.” The news article was based on a scientific study published earlier that week in Environmental Science and Technology Letters, titled, “Perfluoroalkyl Acid Characterization in U.S . Municipal Organic Solid Waste Composts.” The lead author is Youn Jeong Choi of Purdue University. What she and her co-authors found was significant traces of PFAS in compost that included biodegradable packaging–as much as 10 times more than in compost that did not contain those materials.

PFAS are a group of man-made compounds that have been manufactured in the U.S. since the 1940s. They are useful for their flame-retardant and oil- and water-repelling properties. In compostable food packaging, like the “eco-friendly” bowls used by the Chipotle restaurant chain, the chemicals help to keep hot wet foods in the container and not on the customer’s lap. Unfortunately, some PFAS compounds have been found to pose serious health risks, including links to cancer and birth defects. Moreover they have an extremely long half-life, and they accumulate in soil where they can be taken up by plants, and they also find their way to drinking water.

The term PFAS include a wide range of synthetic compounds, and the Purdue-led study found that many of those in the compost samples were shorter chain versions that do not bioaccumulate as actively as other types. A soil scientist on our project, Dr. Steve Ventura, repeated that point shortly after the Popular Science article came out. However, when another article surfaced in early August in The New Food Economy, James Jutrzonka, arguably the most critical player in the current food-waste-to-composting system, sounded the alarm. It did not matter if the science said that the risk of shorter chain compounds found in compost samples posed less of a danger. What mattered for him was the perception that current and potential customers had of his product.

In late summer 2019 he informed Tashjian of Compost Crusader that he would no longer accept any food waste from her that included biodegradable materials, and that included the bags that most of her residential, commercial and institutional customers relied on to safely and cleanly aggregate and transfer their food waste to Tashjian’s trucks.

The compost specifications and summary conclusions that Shultheis of OTIE was developing in the final days of the project address the issue of PFAS. As the project ended on September 30, it was unclear if the city’s Environmental Collaboration Office would allow for the inclusion of compost contaminated with PFAS to be used in green infrastructure projects that did not involve soil for food production. If Jutrzonka cannot find anyone to take the compost on his site that contains these materials, he may need to absorb the cost of landfilling them. As for Tashjian, she is looking into other alternatives, including acquiring access to land to compost the food waste and biodegradable packaging herself. It is unclear, however, what she would do with the finished product if no one will purchase it.

This annual and concluding report from 2019 ends with this very unfortunate development regarding PFAS. We will consider it in light of other aspects of the project in our Research Conclusions section below.

In our hypothesis section of our proposal to SARE, which we restated at the top of our research report, we plainly admitted that our project was not designed to test a specific hypothesis. Instead, it was meant to inform a planning process, in many ways a traditional strategic planning process. But rather than conduct that with a single firm, institution or organization, as is common, we attempted it with a system that involved many firms, institutions and organizations. The research collected data, knowledge and practices related to the goal of scaling up the system of composting of food waste to improve urban and peri-urban soil. From the beginning we intended to characterize the system primarily in terms of supply and demand: supply of food waste and demand for the compost produced from it. Between these two ends of the supply chain stood the processors, or composters, who convert the supply into finished products that satisfy demand.

In Table 2 above we combined the best of our data to present our characterization of the supply of food waste, the capacity of food waste processing, and the demand for compost made from food waste, in terms of both potential and actual quantities. Due to the difficulties we outlined in terms of collecting complete data from all the relevant sources, this characterization is admittedly a rough and partial view of the system.

There are three conclusions we feel most confident about. One is that only a very small portion of the food waste generated in the city and county of Milwaukee is currently being diverted from landfills to composting. A second is that the commercial composting capacity is adequate to handle current food waste quantities, but an expansion of supply, for instance from 1.3% to 8% of county-generated food waste, would require capacity expansion as well. A corollary to this second conclusion is that the system is in a position of risk with its over-dependence on a single processor willing to take "post-consumer" waste. A third conclusion is that best potential to grow demand and thereby allow for supply and processing to expand as well, is the utilization of compost for green infrastructure projects.

All of that said, the new problem confronting the system in the final months of the project raised an issue that was not captured in either Diagram 1 in our 2017 Annual Report or in Table 2 from our 2019 Annual & Concluding Report. Both of those focused on quantities: quantities of food waste, of processing capacity, and demand or utilization of compost. What neither encompassed was contamination.

The issue had been raised back in mid-2017, when Tashjian called SARE project manager Greg Lawless because Jutrzonka from Blue Ribbon Organics was complaining that many of the so-called compostable bags that Tashjian delivered were not breaking down completely in the composting process. The issue was partially resolved by asking all of her residential, institutional and commercial customers to switch a brand that decomposed most effectively.

After that, we did not prioritize the issue of contamination because, compared to the nearby city of Madison, it was a far smaller concern in Milwaukee. A similar pilot in the state's capital city had had its food waste rejected from multiple compost sites and anaerobic digesters because of excess contamination, and ultimately they had to shut the pilot down. (The Madison pilot was reinstated at a small scale for a limited period in August 2019.) Tashjian credited Milwaukee's comparative success to a more effective education strategy for her customers.

The discovery of PFAS in compost that contained biodegradable food packaging and service materials came as a complete surprise. Unfortunately, Tashjian had been rapidly expanding her inclusion of those materials from customers who were trying to reduce their use of plastic. Jutrzonka was already becoming concerned about the quantity of this products which, like the bags two years before, were not all breaking down as well as advertised. When the news broke that these materials contain chemical compounds that pose a serious health risk, Jutrzonka shut the door on them, and Tashjian is facing a major challenge to her current business strategy as a result.

One simple conclusion we can make from this experience from a research point of view is that systems can be very complex, and unexpected developments should probably not be unexpected.

Before making additional final comments about our experience conducting "systems research," we want to give cursory responses to the 12 questions we raised at the start of the project.

- What sources of food waste in Milwaukee are already being composted? In 2017 Tashjian of Compost Crusaders provided us detailed data from the previous year that showed the quantities of food waste she collected from restaurants, schools, food processors, supermarkets, hospital and corporate cafeterias, and households. Furthermore, we learned about the distinctions between pre- and post-consumer waste. Essentially, finding places to divert pre-consumer waste from landfills is much easier. Post-consumer waste is where contamination frequently occurs.

- Who is composting Milwaukee’s food waste now, and where? Our report has mainly focused on only composter, Blue Ribbon Organics of northern Racine County. Another large commercial composter, Sandy Syburg of Purple Cow Organics, was involved in our project early but eventually not at all. From our understanding, his composting in the Milwaukee area is limited to a contract he has with the operator of the Orchard Ridge landfill, he does not take post-consumer food waste, and most of the supply he processes does not come from the city of Milwaukee. The non-profit organization Growing Power was famous for its composting, but the volume of food waste they handled, before dissolving is late 2017, was not nearly as substantial as Blue Ribbon. Another non-profit, Kompost Kids, composts food waste and other organics at two sites in Milwaukee using volunteer labor. Like Growing Power, their quantities are modest compared to Blue Ribbon.

- What are the most promising new sources of food waste? We did not answer this question, except that we learned that most sources of pre-consumer food waste, often referred to as the "low hanging fruit", is already being composted or sent to other tiers of the EPA Food Recovery Hierarchy, such as food for livestock. There is ample post-consumer food waste to feed into the system from many different sources.

- What constrains composters from expanding food waste composting? This is easy: lack of land, especially in or near the city where much of the food waste is generated, along with capital and/or public funding to create a composting operation and associated entrepreneurship.

- What qualities are urban and peri-urban farms and gardens looking for in compost? We received survey responses from 22 farmers, and over the course of the project the participation of farmers was less than we hoped for. The surveys told us that most of the farmers had a pretty good idea of the value of compost, but they quantities they purchase off-farm are rather small. Cost was a stated deterrent for some of them. As for urban farmers in particular, we did work very closely with one. David Johnson of Cream City Farms hosted our compost trials on his farm on the city's North Side. We hoped this would become a focal point for farmers and community members. However, we cancelled our planned field days in 2017 and 2018 for lack of interest. On a few occasions a few farmers visited the site. The buzz about "urban agriculture" in Milwaukee seems to have died down considerably in the two years since Growing Power dissolved. The Institute for Urban Agriculture and Nutrition, which was mentioned prominently in our proposal, was also dissolved in 2017 because of insufficient support from the leadership of six Milwaukee and Madison universities. While gardening programs are still going strong in Milwaukee and provide important relief to food insecure neighborhoods, the prospects for commercial urban agriculture seemed to have dimmed a bit in the city.

- How do different mixes of food waste and other organic material affect compost quality? We were not able to address this question, except for the fact that post-consumer food waste that contains elements not approved as certified organic, and now the much larger issue of PFAS, limits the utilization of that product in food production systems. The waste producers, haulers and composters would need to develop methods of maintaining extremely clean food waste streams if farmers and gardeners are going to enjoy the benefits of the added nitrogen and other nutrients that food waste can add to compost.

- What types of compost are appropriate for different urban farm practices, products and existing conditions? We did not address this question, partly for lack of farmer engagement.