Final report for LNC17-392

Project Information

Despite the rapid expansion of urban agriculture at local, regional and national scales, unique challenges to urban agricultural operations remain unresolved. In the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area (TCMA), Minnesota, urban growers remain challenged by issues related to land access, high public visibility, and the perceived trade-offs between agricultural land use and other, more traditional forms of urban land use. Thus, a data-driven approach to evaluating the ecosystem services provided by urban agricultural best management practices will play a critical role in informing the decisions of policy-makers and providing sustainable outcomes for urban farmers, whose specific management practices and challenges often go overlooked by traditional agricultural research and extension activities. Our team of researchers, farmers and community organizations is uniquely poised to address this need through integrated on- and off- farm collaborative research. Our on-farm approach involves the evaluation of soil quality, water quality and quantity, biological diversity and crop yields at multiple scales for urban agricultural best management practices implemented by our farmer-partners. This is paired with an off-farm replicated approach implemented by our academic partners to allow rigorous comparative data collection without imposing additional constraints on space-limited urban agricultural operations. The expected outcomes of this work include the production of scientific information which can be utilized by policy-makers and farmers to enhance the economic and environmental sustainability of urban agriculture, and the development of a long-term collaborative and information sharing framework which improves outcomes for urban agriculture in the Twin Cities.

The action outcomes of this project align with three project aims: (1) 3 large-scale urban farms and 20 community gardens will use results from our evaluation of ecosystem services to improve amendment practices, yield, and resource protection, (2) policy-makers will be empowered to make data-driven decisions regarding the current and potential land base and ecosystem services from urban agriculture, and (3) networks of communication through academic, farmer and community partners will be strengthened and the Twin Cities urban agriculture community will have an increased number of communication tools for shared information exchange.

The carefully cultivated University-community partner relationships leveraged in this project are the result of more than 2 years of preparatory meetings, preliminary efforts, and collaborative discussions. A UMN OVPR-funded working group brought together community partners and academic collaborators from three institutions (including myself, Dr. Mary Rogers – Horticulture, University of Minnesota; Dr. Chip Small - St. Thomas University; and Dr. Valentine Cadieux - Hamline University) and began with a Sustainable Food Systems colloquia in December of 2015, and culminated in the first annual "Twin Cities Urban Agriculture Workshop" in October, 2016. This working group met quarterly, received input from farmers, growers, and community members; and consolidated the needs for research and education on urban agriculture in the Twin Cities.

These foundational efforts led to the establishment of a network of academic and community collaborators who worked together on a preliminary project in 2016 to develop a framework of mutual trust and respect. During this preliminary work, significant time was spent building relationships, understanding the needs and expectations of community partners, and jointly developing a road map for future on- farm research.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

There is a need for a local, data-driven evaluation of ecosystem services provided by urban agricultural (UA) land use to maximize the benefit from proposed land use strategies (Pulighe et al., 2016). Although the provisioning service of food production is often evaluated as one of the most tangible benefits of UA (McClintock et al., 2013), this represents just one component in a highly diverse array of ecosystem services potentially provided by UA (Calvet-Mir et al., 2012). Database searches of the peer-reviewed literature reveal a significant bias towards research on ecosystem services provided by agriculture in rural areas (e.g. Smukler et al., 2012), which is important because UA is significantly different from peri-urban or rural agriculture in several ways. UA tends to rely heavily on intensive inputs of locally-derived materials, and the repeated application of these amendments has been shown to dramatically increase soil quality and vegetable crop yields in degraded areas (Beniston et al., 2016). Additionally, UA typically occurs within a matrix of highly urbanized, low-diversity land-uses dominated by impervious surfaces, making the ecosystem services resulting from UA even more critical, and in proximal vicinity to larger populations which could benefit from those services (Richardson and Moskal, 2016). Urban agricultural land uses have the potential to generate a high degree of synergy among ecosystem services and thus provide significant benefits to urban populations relative to competing land uses such as vacant lots or turfgrass (Bennett et al., 2009). Several studies have investigated other aspects of provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural services from UA, but few have done so holistically, and none in cold climates analogous to the TCMA.

This work evaluates and quantifies a suite of ecosystem services provided by UA in the TCMA and includes a suite of regulating, supporting and cultural services in addition to the provisioning service of crop yields. A broader, more holistic perspective on these services will lead to better, more informed decisions by policy-makers regarding the benefits of UA in the TCMA.

Research Methodology

The approach to ecosystem services assessment in this study is underpinned by integrated on- and off-farm data collection at both plot and site scales. The off-farm replicated plots allow us to connect and extend on-farm observations (which are necessarily smaller in scale, limited in treatment, and more variable) to additional crop functional types and treatments. For the on-farm component, we utilize a well-developed, highly collaborative, and integrated network of for-profit (Growing Lots – Minneapolis), non-profit (Frogtown Farm – St. Paul & Mashkikii Gitigan – Minneapolis), and community garden (Urban Farm and Garden Alliance – St. Paul) growers who have agreed to provide space for replicated studies (see letters of support attached). We will then contrast these urban agricultural management plots with turfgrass and unmanaged vacant lots – the two most probable open-space alternative land uses to UA in the TCMA and other cities (McClintock et al., 2013). Methodological details of this data collection are provided below to demonstrate the scale and depth of data which will be available for the proposed CURA-funded quantitative ecosystem services assessment.

On-Farm Data Collection: At each partner site, we will establish triplicate plots (1m2) in the 2018 growing season to evaluate three urban agricultural management practices: (1) No amendment, (2) Compost amendment = single source municipal food waste compost, high application rate based on crop nitrogen (N) demand - using the ATTRA compost rate calculator, and (3) a "Growers Choice" practice (which partners will use to leverage the data collected in the project to explore questions of their own). Each on-farm plot will be planted with collards (chosen because all partners could agree on this as a valuable crop for their operation). The data emerging from the evaluation of these practices will be compared to “reference” land use data collected from plots on vacant lots and unmanaged (or mown only) turfgrass - either on-farm, adjacent to farms, in open space/boulevards, or in the surrounding neighborhood.

Off-Farm Data Collection: Dr. Chip Small (St. Thomas University) and I are integrating the off-farm and on-farm research design by collaboratively assessing replicated plots at the St. Thomas University (St. Paul, MN) Stewardship Garden. These consist of 36 separate 4m2plots, with each 1m2quadrant planted to a different vegetable crop functional type (Bell Peppers, Bush Beans, Carrots, and Collards), under 6 different treatments of (1) single source municipal food waste compost - low rate, based on crop phosphorus (P) demand, (2) single source municipal food waste compost - high rate, based on crop N demand, (3) no amendments, (4 & 5) reserved for replication of "Growers Best" practices, and (6) established turfgrass, with 6 replicates per treatment.

Metrics of provisioning services: Crop yields and plant quality. For on-and off-farm plots, crop and biomass yields (both edible portions and total biomass) will be measured at the time of harvest. Our approach to yield evaluation at the site scale will follow recommended protocols informed by previous work funded by the CURA Kris Nelson Community-Based Research Program (Grewell, 2015). Plant quality for both on-and off-farm collard plots will be assessed through triplicate tissue samples two times during the growing season (mid-July, September) by foliar nitrate and chlorophyll measurements.

Metrics of regulating services: Soil quality, water quality, infiltration, and gas fluxes. Soil quality assessments will be conducted by measuring parameters relevant to plant growth, water movement and nutrient cycling, including:

- Soil chemical properties (organic carbon, pH, nitrate, ammonium, available P and exchangeable potassium (K),

- Soil physical properties (bulk density, soil texture, aggregate stability, infiltration, and hydraulic conductivity), and

- Soil biological properties (microbial community phospholipid fatty acids and extracellular enzymes).

These will be measured prior to the establishment of plots and once each year thereafter at three depth increments (0-4", 4-8" and 8-12") in each plot. Prior to plot establishment, lysimeters (which collect soil pore water under conditions of saturated flow) will be installed at 12" below the soil surface. Total leachate volume will be extracted once per week from each plot. Nitrate, ammonium and phosphate concentrations in leachate water will be measured once per week for one replicate from each treatment, and biweekly for all other replicates. Biweekly measurements of carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O) gas fluxes will be taken throughout the growing season using the static chamber method.

Metrics of supporting services: Biodiversity. Annual insect biodiversity inventories will be performed at each partner UA site, in the St. Thomas Stewardship Garden plots, and in adjacent or nearby boulevards, vacant lots, or parks. At each location, site-level data will be collected including vegetative diversity and ground cover at a 100 x 100 m plot spatial scale. This will include areal coverage of impervious surface, mulch, bare ground, grass, woody vegetation, and herbaceous/weed vegetation (Quistberg et al., 2016). Twice monthly from June-September we will collect and identify insects collected in pitfall traps (3 per site), sticky cards (3 per site), and aerial net sweeps. Earthworm biomass will be quantified prior to the establishment of plots and at the end of the final project year utilizing a liquid mustard extraction protocol (Resner et al., 2015). Earthworm ash-free biomass, species diversity, and functional group will be determined.

Metrics of cultural services: Education, aesthetics and discovery. Social and cultural services (education, aesthetics and discovery) in UA and community gardens in the TCMA have been preliminarily investigated by previous work funded through the CURA Kris Nelson Community-Based Research Program Center (Grewell, 2015) under the concept of “social yield”. This work was completed in collaboration with the Urban Farm and Garden Alliance (St. Paul), one of our grower-partners. Collaborator Dr. Valentine Cadieux (Twin Cities Agricultural Land Trust (TCALT)/Hamline University) will assist in the design and implementation of surveys which assess the perceived importance of a range of cultural services provided by various land uses in the TCMA. These surveys will utilize a socio-cultural valuation approach, such as has been used in previous ecosystem service assessments (Camps-Calvet et al., 2016), and will include perceptions of cultural services such as place-making, social cohesion, aesthetic enjoyment, nature and spiritual experiences, relaxation and stress reduction, learning and education, and maintenance of cultural heritage (Camps-Calvet et al., 2016).

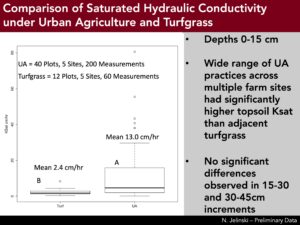

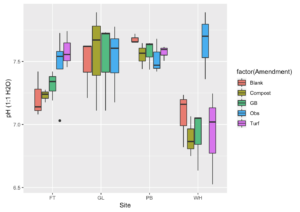

Results: Year 1 (2018). The preliminary results from Year 1 (2018) of our work have revealed some very interesting trends and patterns that are relevant to the academic community, our farmer collaborators, policy-makers, and municipal planners. Perhaps one of the more interesting preliminary results is our initial finding that all urban agricultural land uses we investigated in Year 1 had (on average) 5x higher hydraulic conductivity and lower bulk density in the 0-15cm depth increments of the soil as compared to unmanaged turf grass (Figure 1). This is a significant result because it points to one of the major potential co-benefits of urban agricultural land use as increased infiltration and water storage. Based on this preliminary result, we will be expanding our hydraulic conductivity sampling in Year two to include many additional sites.

(Figure 1). Saturated hydraulic conductivity differs significantly in the top 15cm of sites urban agricultural land use as compared to adjacent unmanaged turf grass.

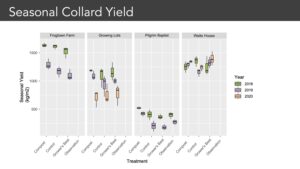

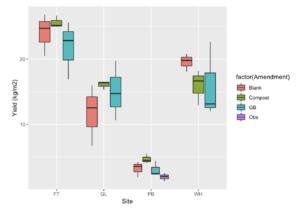

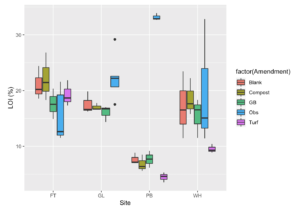

Preliminary results perhaps of most local interest too our farmer-collaborators (and results that can be utilized by them to improve their own management practices are presented in Figures 2-7. Figure 2 shows the variability in seasonal collard yield by site (partner) and treatment within site. In particular, this figure shows that Growers Best (GB) practices (those practices chosen by our partners) may not have significantly increased yield above control or compost-only additions to soil. We will continue to monitor these same practices as we implement them in project years 2-3. Additionally, seeing their own data in comparison to others is a valuable learning experience and an opportunity for farmer-to-farmer exchange that seldom exists in urban agriculture.

(Figure 2). Seasonal yield variability between partner sites and amendments.

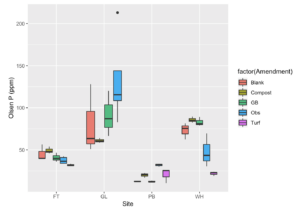

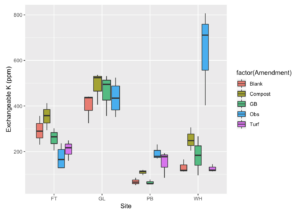

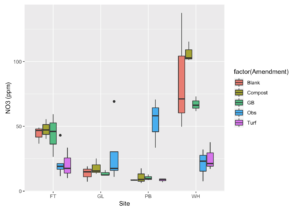

Our soil chemical data tended to underlie what has been seen in other urban agricultural systems. Levels of available N (Figure 3), P (Figure 4), and K (Figure 5) tended to be at high or very high levels for many of our partners. Some were surprised at how high their P values were. We are continuing to work up our seasonal water quality data to investigate the linkage between soil nutrient values and near-surface leachate.

(Figure 3). Olsen P variability between partner sites and amendments.

(Figure 4). Exchangeable K variability between partner sites and amendments.

(Figure 5). NO3 variability between partner sites and amendments.

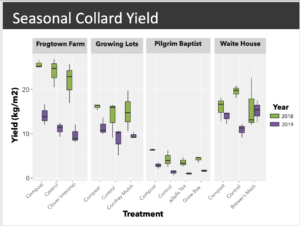

The data for pH (Figure 6) show that these urban agricultural soils tend to be neutral to slightly alkaline in pH (a trend we have observed in most urban topsoils in the Twin Cities Metro Area). These results showed our growers that they really do not need to be concerned with adjusting their soil pH, changing some misconceptions.

(Figure 6). pH variability between partner sites and amendments.

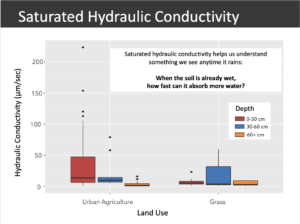

Our organic matter data (LOI%, Figure 7), shows that with the exception of one site, these urban agricultural soils are very high in organic matter (largely due to the way they are managed and amended).

(Figure 7). Organic matter variability (as Loss on Ignition %) between partner sites and amendments.

Update: Year 2 (2019). We were able to continue our on-farm research and strong community partnerships in the second year of this project. Methodological details and study sites remained the same. However, the second year of field data has brought some additional results and synthesis. We have close relationships with our farmer-partners, and have been sharing this preliminary data with our farmer-partners and policy-makers.

Yields. Collard yields were generally lower across all sites in 2019 as compared to 2018 (Figure 8). This was to be expected because 2019 was a significantly cooler and wetter growing season than 2018. However, our data show, across all sites, the positive impact of compost addition in terms of buffering yield loss in 2019. Additionally, we continue to see interesting trends in the impact of "Growers Choice" practices, that were chosen at the beginning of the project by each grower-partner as a participatory aspect of this research. The Growers Choice practice that seemed to have the most positive impact on yields in the 2019 season was the addition of Brewer's Mash, (a treatment chosen by the farm manager at Waite House) (Figure 8).

Soil Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity. We continued to measure soil saturated hydraulic conductivity at urban agriculture sites and adjacent turf grass (as a potential alternative land use) throughout 2019. We now have data from multiple soil depths across multiple sites. This preliminary data is of interest to our grower-partners, but is also relevant to stakeholders at municipal agencies interested in the impacts of urban agriculture on stormwater quantity and quality. This preliminary data shows that saturated hydraulic conductivity may be higher in the top 30cm at urban agriculture sites (all management practices lumped) relative to unmanaged turf grass (Figure 9). Subsoil depth increments (30-60cm, 60+ cm) were not significantly different between management practices.

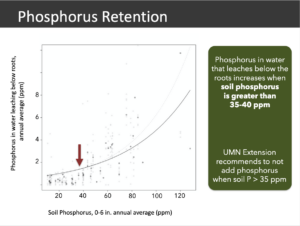

Soil and leachate phosphorus. We have begun to analyze the first two seasons of soil phosphorus data in conjunction with water leachate P data that we collect weekly from our lysimeters that collect water leaching below the rooting zone. Our data shows that soil water leachate P increases significantly in our on-farm plots when soil P (Olsen P) exceeds 35-40 ppm. This coincides with the current recommendations from UMN extension for high quality vegetable crops. This information was shared with growers and can be used as they interpret their soil testing results and plan amendments and nutrient management plans in urban settings (Figure 10). These preliminary results are consistent with off-farm work being done by collaborator Small (Small et al., 2018, Small et al., 2019).

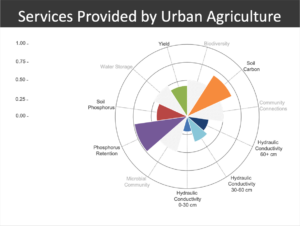

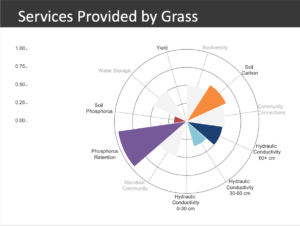

Metrics of Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Agriculture - Rose Diagrams. As we begin to analyze our preliminary data, one of our major tasks in alignment with our project goals has been to integrate the many metrics of ecosystem services that we are measuring at our partner sites and synthesize the data into a digestible format. Our initial attempt to do that has been to construct rose diagrams, showing the normalized values of each of these metrics relative to the highest value measured at any of our study sites. We have utilized the preliminary data from 2018 and 2019 to do this for our urban agriculture and turf grass plots - note that there is some data and metrics which we have not yet analyzed and synthesized - these are shown with grey crosshatching in the current figure, but will be added in future iterations (Figure 11a and 11b). These rose diagrams communicate the tradeoffs associated with different land uses. For example, soil carbon storage, food production (yield), and topsoil (0-30cm) hydraulic conductivity are higher under urban agriculture than turfgrass, while phosphorus retention may be higher under turf grass than urban agriculture. It is our hope that these type of syntheses can be used in the future by policy-makers to evaluate the impacts of urban agriculture policies on the ecosystem services provided by urban lands.

Update: Year 3 (2020). Year three of this project was incredibly challenging due to the covid-19 pandemic and the protests/uprising related to the killing of George Floyd. These events directly affected all of our partners (two of our partners, located in Minneapolis (Growing Lots and Waite House are located in close proximity to the epicenter of the protests and George Floyd square). Community members in the immediate area were impacted by not only the uprising and protests, but also the lack of food availability. Both of our Minneapolis partners essentially functioned as de facto food distribution hubs for the community between May and July of 2020. This significantly delayed planting and normal agricultural operations. Nevertheless, we were able to support these partners during this time and also continue on-farm data collection throughout 2020 as best as possible. We had 2 St Paul partners on this project - Frogtown Farm and the Urban Farm and Garden Alliance. Frogtwon Farm made the decision to cease operations in April of 2020 due to the covid-19 pandemic, and let go of their farm manager, who transitioned to becoming a researcher on our project and is now an incoming masters student. For these reasons, data was not collected on Frogtown Farm during the 2020 season. The Urban Farm and Garden Alliance remained in operation and we were able to continue our research plots and collaboration with them. Although our research was significantly impacted in 2020, the depth of our relationship and trust with our community partners grew stronger. Our group provided ongoing volunteer support to our partners which continued to build our relationships beyond specific research activities. Despite the challenges posed by 2020, we were able to continue the following activities: maintenance and monitoring of collard yields on established experimental plots, sampling for soil chemical and physical properties, sampling for earthworm abundance, collection of leachate from lysimeters, measurement of nitrate and phosphate concentrations in root zone leachate. Due to the delay in data collection and significant restrictions on lab work at University facilities due to covid-19, we are still processing the 2020 samples and data and will add the results of analysis to this 2020 reporting section once complete.

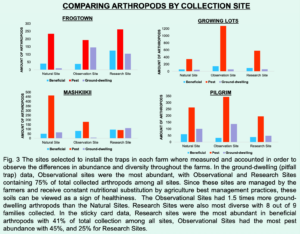

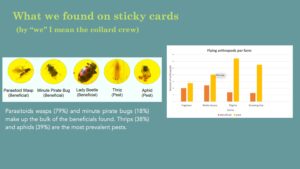

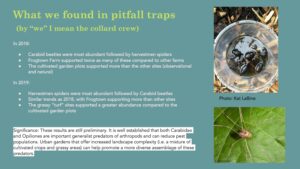

Update (Year 4 - 2021). We requested and received a no-cost extension for this project to 09/30/2021. This enabled us to complete data collection and augment activities from the 2020 season which were severely disrupted due to COVID-19. The results shown here are preliminary as they have not yet been through peer-review. However, they will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals in manuscript form and will also form a portion of a graduate dissertation (Jennifer Nicklay). Results from multiple years of data (2018-2019; insects surveys were not completed in 2020 due to the covid-19 pandemic) were presented at a "Community Land and Food Gatherings" meeting with community partners in March, 2021. This presented the results from insect surveys completed by Naomi Candelaria Morales and Yashira Gutierrez Cardona. We found that (based on our insect surveys), arthropods in functional groups deemed as pests were much more prevalent than those deemed as beneficial (at least in the context of our sampling at the partner urban farms). However, the abundance and proportion of beneficial, pest and ground-dwelling arthropods was widely variable between sites and between treatments within sites:

Figure 12. Column plot of arthropod individual numbers for natural (non-farmed), observational, and research sites within each of 4 urban farms. These arthropods were collected through a combination of sticky cards and ground traps..

Figure 13. Column plot showing the distribution of beneficial and pest insects collected with sticky cards at urban farm sites in Minneapolis-St. Paul.

Figure 14. Summary of 2018-2019 insect data.

Additionally, the results from all three years of data were presented and discussed at an international mini-symposium on "Urban Agriculture as Blue-Green Infrastructure" hosted by Dr. Genevieve Metson (Linköping University, Sweden). We found that collard green yield was highly variable between partner sites and exhibited significant inter-annual variability. On sites with sandy soils that had low organic matter (Pilgrim Baptist), yields were highest and least variable year-on-year in the compost treatment. At other sites where either a) soil organic matter was higher and soil textures were finer (Frogtown Farm) or crops were grown predominantly designed beds and media (Growing Lots and Waite House), individual treatments were less important than inter annual variability in determining yield:

Figure 15. Seasonal collard yield data at urban farm sites by treatment for 2018-2020. No yield data is shown for Frogtown Farm for 2020 due to disruptions in research activities from the covid-19 pandemic. Yield data for 2020 at Pilgrim Baptist is currently under review and not shown on the plot.

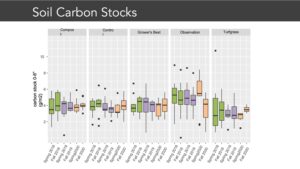

Carbon stocks in the top 6 inches of soil did not show significant increases from 2018-2020. However, in the compost treatment, the carbon stocks became less variable compared to the control, grower's best, and observation treatments. Interestingly the observational plots (plots where measurements were taken on existing on-farm, but no research interventions were applied) had the highest carbon stocks in the top 6 inches, while plots under adjacent turf grass had the lowest.

Figure 16. Soil carbon stock data in the top 0-6 inches of soil by farm and treatment for 2018-2020.

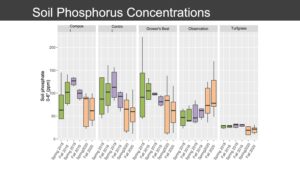

Soil phosphorus concentrations in the top 6 inches generally varied around the mean or decreased with the exception of the observational plots (plots where measurements were taken on existing on-farm, but no research interventions were applied). However, these phosphorus concentrations, although increasing, were similar in magnitude to the other treatments. All phosphorus concentrations under urban agriculture were higher than those under adjacent turf grass, which were significantly lower.

Figure 17. Soil phosphorus concentration data in the top 0-6 inches of soil by farm and treatment for 2018-2020.

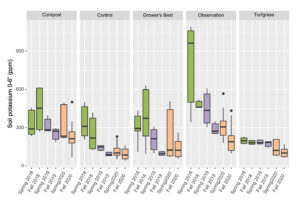

Soil potassium concentrations in the top 6 inches decreased across all treatments from 2018-2020. Initially, potassium concentrations started out higher in the observational plots (plots where measurements were taken on existing on-farm, but no research interventions were applied), but by 2020 had declines to similar ranges as the research plots. Adjacent turf grass plots also demonstrated potassium decline from 2018-2020, but started at much lower levels in 2018.

Figure 18. Soil potassium concentration data in the top 0-6 inches of soil by farm and treatment for 2018-2020.

The objectives of this research were to evaluate metrics of ecosystem services provided by urban agricultural management practices under a plot-based research design with multiple treatments (in-ground control, compost-only application to meet crop P demand, grower's best, and adjacent turf grass) as well as observational measurements of managed food production areas outside of controlled research plots. We measured crop yields, physical and chemical metrics of soil quality, insect diversity, and social and cultural values and services provided by urban agriculture. The conclusions described here are preliminary as they have not yet been through peer-review. However, they will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals in manuscript form and will also form a portion of a graduate dissertation (Jennifer Nicklay), expected in 2022.

Crop Yield. We found that crop yields (collard greens were selected as the crop of choice) were highly variable across urban agricultural sites and between years. On sites with sandy soils that had low organic matter (Pilgrim Baptist), yields were highest and least variable year-on-year with compost application. At other sites where either a) soil organic matter was higher and soil textures were finer (Frogtown Farm) or b) crops were grown in designed beds and media (Growing Lots and Waite House), individual treatments were less important than inter annual variability in determining yield. These results show that existing soil media or quality may be more important than deciding which, if any, amendments to apply when establishing a new food production site in an urban area. Particularly due to a lack of soil survey information in most urban areas as well as the potential for high variability between sites, it is extremely important to conduct foundational soil testing prior to establishing large urban farms, as at least over a three year time frame this could have a greater determination on crop yield than any grower interventions.

Metrics of Soil Quality (Chemical). In the conclusions here, we will highlight three soil chemical metrics - carbon, phosphorus, and potassium. Carbon stocks in the top 6 inches of soil did not show significant increases from 2018-2020. However, in the compost treatment across sites, the carbon stocks became less variable compared to the control, grower's best, and observation treatments. Interestingly the observational plots (plots where measurements were taken on existing on-farm, but no research interventions were applied) had the highest carbon stocks in the top 6 inches, while plots under adjacent turf grass had the lowest. It is important to note that our sampling only allowed us to calculate carbon stocks to 6 inches. In systems where amendments have the potential to build absolute elevation, therefore, it is important to consider deeper depths, and this is a limitation of our current study. We recommend future studies sample deeper. Soil phosphorus concentrations in the top 6 inches generally varied around the mean or decreased over time. All phosphorus concentrations under urban agriculture were higher than those under adjacent turf grass, which were significantly lower. All of the phosphorus concentrations measured under food production were sufficient for crop production (> 35ppm), and often well in excess of this sufficiency threshold. Our data shows that soil water leachate P increases significantly in our on-farm plots when soil P (Olsen P) exceeds 35-40 ppm. This coincides with the current recommendations from UMN extension for high quality vegetable crops. This information was shared with growers and can be used as they interpret their soil testing results and plan amendments and nutrient management plans in urban settings. This shows that there are significant opportunities to increase the specificity of nutrient management and the timing of nutrient applications under urban agriculture. Soil potassium concentrations declined across all treatments from 2018-2020. While most of the concentrations were high enough for crop sufficiency, this points to the need to potentially augment amendment strategies under urban agriculture with amendments that have higher potassium concentrations. The differences in trends over time between phosphorus and potassium are striking and show that in the long-term most urban agricultural management practices may result in an excess of phosphorus and a deficieny in soil potassium.

Metrics of Soil Quality (Physical). We found that saturated hydraulic conductivity was higher in the top 30cm under urban food production areas than under adjacent turf grass areas. This is likely because of increased organic matter rich amendment application and potentially due to tillage practices. Subsoil depth increments (30-60cm, 60+ cm) were not significantly different between urban agricultural management practices or between urban agriculture and turf grass sites. Further studies should incorporate watershed scale modeling (such as with the InVEST model) to determine whether the increase in hydraulic conductivity in the upper 30cm can make a significant difference in landscape scale water storage under intense rainfall events with varying scenarios of food producing area within the watershed.

Insect Diversity. We found that abundance and richness of key arthropods differed among all garden sites, and can be related to the local and surrounding ecosystem. Parasitoids wasps (79%) and minute pirate bugs (18%) make up the bulk of the beneficials found. Thrips (38%) and aphids (39%) are the most prevalent pests. Green spaces such as these will provide an opportunity for social, nutritional, health, and ecological benefits, especially in low-income neighborhoods, that minimize food insecurity. As increasing urban development continues to expand, these spaces can focus on conservation of richness and abundance of beneficial species that provide ecosystem services necessary for ecosystem functioning, and better understand the aspects that contribute to change in trophic groups, fundamental to long-term management. The shifts of arthropod abundance and richness for each site can be associated to crop management, surrounding plant abundance and diversity, location, soil quality, and agriculture or urban development history, which could be an interest of study for continuing research. Our results highlight key pests and beneficial arthropods common to urban community garden sites; the four urban garden sites showed differences in diversity and abundance of ground-dwelling arthropods, such as spiders (Arachnida) and beetles (Coleoptera), and flying beneficial to pest ratio, in which a balance of the ecosystem can be observed. The results also reveal trends based on surrounding plant diversity, and can be used for follow up studies with the goal of improving urban ecosystem functioning by conserving beneficial arthropods. These results are still preliminary. It is well established that both Carabidae and Opiliones are important generalist predators of arthropods and can reduce pest populations. Urban gardens that offer increased landscape complexity (i.e. a mixture of cultivated crops and grassy areas) can help promote a more diverse assemblage of these predators.

Social and Cultural Values and Services. Collaborations between urban growers, policymakers, scholars, and communities that leverage urban farms and gardens as sites of ecological, social, and political transformation represent spaces of urban agroecology. In fall 2019, we conducted our first formal evaluation of the participatory processes implemented in our current project with the objectives to (1) identify processes that facilitated or were barriers to authentic collaboration and (2) understand the role of relationships in the participatory processes. Qualitative surveys and interviews were developed and conducted with researchers, partners, and students. Analysis revealed that urban agroecology research provided a space for shared learning, which was facilitated through co-creation of research, embodied processes, and relationships with people, cohorts, and place. The results of this work were published in a peer-reviewed article, and formed the foundation of a subsequent book chapter co-authored by J. Nicklay and V. Cadieux.

Education

Our educational approach is fully integrated into our project aims and intended to maximize the impact of our project across the Twin Cities urban agriculture community. Our outreach activities address each of the three levels of the Twin Cities urban agricultural community: 2 for-profit and 1 non-profit farming operations, 431 community gardens, and over 1,000 (scaled estimate from Taylor and Lovell, 2012) food producing households.

1. Annual Urban Agriculture All-Hands Meetings. Based on a pilot workshop organized in 2016 (organized by Dr. Rogers, with Dr. Small and Dr. Jelinski as presenters and Dr. Cadieux as co-facilitator), we expect academic, farmer, grower, and community participants in these meetings each year. Post workshop surveys indicated that interest and demand were high, and 80% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they had a better understanding of urban agricultural issues after the workshop. We expect that the addition of data from our proposed project will only further enrich these discussions and participant attitudes.

2. Annual presentations to Minneapolis Homegrown Food Council and St. Paul-Ramsey Food and Nutrition Council. Through the project period, we will make annual presentations on result updates to the two Food Councils organized for Minneapolis and St. Paul. These councils serve as a direct conduit to policy-makers and citizen-members and are an effective way to present research in an environment where data can effect change at those levels.

3. "Soil Kitchens" and downstream information transfer. Since 2015, Dr. Jelinski has been conducting on-site soil screening and community outreach events. To date, these events have resulted in over 700 direct contacts with community members - these events will serve as a way to communicate research results to community and household gardeners. Frogtown Farm hosts "Knowledge Share" programs which facilitate the bi-lateral transfer of knowledge from farm managers to community members, and vice-versa. The TC Urban Ag website has been revamped and is designed as an accessible resource for farmers, growers and community members which will have content built by students in conjunction with project activities.

4. Peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations. The production of peer-reviewed literature in conjunction with national conference presentations will allow the Twin Cities and North Central Region to enhance our voice in the national urban agriculture conversation.

Project Activities

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Tuesday, February 6th, 2018. Urban Agriculture "All-Hands" Meeting. Initial planning and coordination meeting with all project partners and collaborators to layout project plans, project logistics, and collaboratively make decisions on best practices for project management, data sharing, and experimental design. +6 Farmer contacts

Saturday, June 17th, 2018. Community Soil Lead Screening, Frogtown Farm Market Saturdays. +2 Farmer Contacts and +25 Community Contacts. Free on-site screening for soil lead and education/outreach regarding best practices to reduce exposure and avoid high lead soils.

Wednesday, August 8th, 2018. Picnic Tour and Exploration of the New Urban Food System Landscape, Urban Food Systems Symposium. Assisted with tour organization, demonstrated experimental design, preliminary data, and community partnerships to an audience of practitioners and researchers. +20 academy contacts, + 4 farmer contacts

Thursday, September 12th, 2018. Collaborative Evaluation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Agriculture in the Twin Cities. Presentation to Homegrown Minneapolis Food Council Meeting, Minneapolis, MN 12SEP2018. +2 policy makers, + 2 municipal employees, + 3 farmers, +18 community contacts.

Wednesday, October 16th, 2018. Presentation to Ramsey County and Washington County Master Gardeners. Roseville, MN. "Lead in Urban Soils" Presenter, N.A. Jelinski. +89 Master Gardeners. Education/outreach regarding best practices to reduce exposure and avoid high lead soils.

Saturday, December 1st, 2018. Urban Farm and Garden Alliance 3rd Annual Greens Cookoff. Graduate student and technician were on event planning committee. Collard greens from research plots were utilized by community members in greens cookoff. N. Jelinski and undergraduate researchers volunteered at event. + 110 community contacts.

Urban Farm and Garden Alliance Monthly Meetings. May 2018 - December 2018. Last Thursday of every month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings to provide consultation, expertise, and timely updates on project logistics and preliminary results. +2 Farmer Contacts and + 10 Community contacts.

Rondo Reconciliation Meetings. May 2018 - December 2018. Every second Thursday of the month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings. Includes community members that aren’t necessarily related to farming +12 community contacts.

Wednesday, March 6th, 2019. Urban Agriculture "All-Hands" Meeting. Annual planning and coordination meeting with all project partners and collaborators to layout project plans, project logistics, and collaboratively make decisions on best practices for project management, data sharing, and experimental design. +7 Farmer contacts, +1 municipal staff, +1 University extension staff.

Community Soil Screening Event at Frogtown Farm. Thursday, June 13th, 2019. Community Soil Lead Screening, Frogtown Farm Market Thursdays. +2 Farmer Contacts and +21 Community Contacts. Free on-site screening for soil lead and education/outreach regarding best practices to reduce exposure and avoid high lead soils.

Twin Cities Metro Growers Network - Exploring Urban Soils Research and Compost at Growing Lots. June 28th, 2019. We talked soils and compost, and learned about research looking at the potential of urban farms and gardens to improve water infiltration and reduce runoff, and a host of other benefits. +8 farmer contacts, +16 community contacts, +2 municipal staff contacts.

Community Soil Screening Event at Open Streets Franklin. Sunday, August 25th, 2019. Community Soil Screening, Open Streets Franklin. +18 Community Contacts. Free on-site screening for soil lead and education/outreach regarding best practices to reduce exposure and avoid high lead soils.

Monday, November 25th, 2019. Collaborative Evaluation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Agriculture in the Twin Cities. Presentation to Homegrown Minneapolis Staff, Minneapolis, MN. +2 policy makers, + 2 municipal employees.

Urban Farm and Garden Alliance Monthly Meetings. January 2019 - December 2019. Last Thursday of every month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings to provide consultation, expertise, and timely updates on project logistics and preliminary results. +2 Farmer Contacts and + 10 Community contacts.

Rondo Reconciliation Meetings. June 2019 - September 2019. Every second Thursday of the month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings. Includes community members that aren’t necessarily related to farming +12 community contacts.

Nicklay, J.A., K. LaBine, N.A. Jelinski. Community-University Collaboration for Participatory, Interdisciplinary Urban Agriculture Research That Supports Disciplines, Movement, and Practice. Oral Presentation - Presenter: J.A. Nicklay. 2019 Soil Science Society of America Conference, 06-09JAN2019, San Diego, CA. [2] 3rd Place UAS Division Student Contest.

E. Bell, M. Chaney, T. LaShae, M. Anderson, C. Baglien, N.A. Jelinski. The Future of Urban Agriculture. Panel Session Presentation. 2019 Food Justice Summit, 04-06NOV2019, Duluth, MN. [3]

Nicklay, J.A., V. Cadieux, N.A. Jelinski, K. LaBine, M. Rogers, G.E. Small. Initial trends in ecosystem service metrics of urban agriculture in Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN. Oral Presentation – Presenter: J.A. Nicklay. 2019 ASA-CSSA-SSSA International Annual Meetings, San Antonio, TX 10-13NOV2019. [2]

Jelinski, N.A., K. LaBine. Urban Soil Interpretations. Oral Presentation – Presenter: N.A. Jelinski. 2019 ASA-CSSA-SSSA International Annual Meetings, San Antonio, TX 10-13NOV2019.

Nicklay, J.A., Jelinski, N.A., LaBine, K., Cadieux, K.V., Rogers, M., Smell, G.E. Initial Trends in Ecosystem Service Metrics of Urban Agriculture in Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN. 2020 Urban Food Systems Symposium. Hosted by Kansas State University, Virtual, 14OCT2021.

Nicklay, J.A., K.V. Cadieux, M.A. Rogers, N.A. Jelinski, K. LaBine, G.E. Small. 2020. Facilitating Spaces of Urban Agroecology Learning: A Framework for Practicing Participatory Community-University Partnerships. 4(143). Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00143

Urban Farm and Garden Alliance Monthly Meetings. January 2020 - December 2020. Last Thursday of every month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings to provide consultation, expertise, and timely updates on project logistics and preliminary results. +2 Farmer Contacts and + 10 Community contacts.

Rondo Reconciliation Meetings. June 2020 - September 2020. Every second Thursday of the month - graduate student, technician, and undergraduate researchers attend meetings. Includes community members that aren’t necessarily related to farming +12 community contacts.

Cadieux, K.V. & Nicklay, J.A. 2020. Community Labs in AgriFood Teaching. Paper presented at American Association of Geographers, Virtual. 6 Apr.

Nicklay, J.A., Jelinski, N.A., LaBine, K., Cadieux, K.V., Rogers, M. & Small, G. 2020. Initial Trends in Ecosystem Service Metrics of Urban Agriculture in Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN. Oral Session presented at Urban Food System Symposium, Virtual. 14 Oct.

Bowness, E., Nicklay, J.A., Liebman, A., Cadieux, K.V., & Blumberg, R. 2021. Navigating Urban Agroecological Research with the Social Sciences. In M. H. Egerer & H. Cohen (Eds.), Urban Agroecology: Interdisciplinary Research and Future Directions. CRC Press. (Role: co-primary author)

Nicklay, J.A. 2021. Community Science in Urban Agroecology: exploring the roles of farms and gardens in urban socio-ecological systems. Seminar presented at the University of Minnesota Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change Brown Bag Lunch Series, Virtual. 19 Mar. https://mediaspace.umn.edu/media/t/1_ant62ry4/197902193.

Nicklay, J.A. 2021. Participatory data analysis in urban agroecology: Centering relationships and liberation to envision just food systems. Oral Session presented at Dimensions of Political Ecology Conference, Virtual. 20 Feb.

Nicklay, J.A. 2021. Urban Agroecology – a contribution to the Video Lexicon of Community Geography. Lighting Paper presented at American Association of Geographers Conference, Virtual. 8 Apr. https://cgcollaborative.org/video-lexicon/

Learning Outcomes

- Data Interpretation - Soil Nutrients and Chemical Properties

- Data Interpretation - Soil Hydraulic Conductivity and Physical Properties

- Data Interpretation - Insect Biodiversity

Project Outcomes

"I am a food systems coordinator with a large non-profit in the Twin Cities in Minnesota who work focuses on free meal programs, urban agriculture, and food shelves that serve around 13,000 people per month. One thing that I hear a lot in my position, working between community members and researchers, is that our community members constantly feel like they are part of a research project. That they are not humanized. That these privileged academics are here to tell the people in the neighborhood how they have to live, what they are doing wrong, or what they could do better. I never once felt that way about this research team. They were humble and gracious, conducting research while providing much needed fresh greens to our community cafe to serve or our food shelf to give out to the community for free. They focused on providing a benefit to the community while conducting research in a non-intrusive way. This idea was epitomized by the fact that they ate lunch with our community members every time they had a chance. Researchers and students didn't shy away from sitting at a table with our community members experiencing homelessness that I have seen other researchers stay away from. Instead, they sat down and had conversations with these folks. Asked them what they wanted to see done in the neighborhood in regards to agriculture. The team knew these folks had as many brilliant ideas about our community as any researcher did."

Information Products

- Community-University Collaboration for Participatory, Interdisciplinary Urban Agriculture Research That Supports Disciplines, Movement, and Practice

- Collaborative Evaluation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Agricultural Best Management Practices in the Twin Cities

- 2018 NCR-SARE All-Hands Meeting White Paper

- Facilitating Spaces of Urban Agroecology: A Learning Framework for Community-University Partnerships

- Evaluating key pest and beneficial arthropods in urban community garden sites in the Twin Cities metropolitan area