Final report for LNC19-420

Project Information

Examining the role of shelterbelts (tree plantings) on early-season honey production and hive growth of honeybees in the North Central Region (NCR). Pollinators, particularly managed honey bees (Apis mellifera), are critical to food production and sustainable agriculture. Annually, $215 billion of global food production is dependent upon honey bee pollination services, indicating the importance of these organisms to global food security. More specifically, honey production is an important revenue source in many communities across the NCR. Despite this economic and ecological importance, honey bees are under threat from many sources including intensified agricultural practices and continued loss of perennial vegetation. As these threats persist, reductions in the temporal availability of food resources, especially in the early growing season, may be reducing honey bee survivorship and limiting honey production.

Our preliminary observations and communications with beekeepers suggest shelterbelts could provide a crucial food source for bees when other resources are scarce. However, research has not evaluated shelterbelts for pollinator use, particularly in the resource-limited early growing season. We examined the use and effect of shelterbelts on early-season honeybee colony growth in North and South Dakota, the top two honey producing states in the United States.

To address this, we monitored 268 honeybee colonies across 68 apiaries from 2020-2022. We placed scales to monitor hourly weights at two colonies per apiary and pollen traps under two additional colonies per apiary which were used to gather pollen on a weekly basis. Our results suggest that honeybee colony weights did not differ based on the amount of shelterbelt cover within a 1-mile radius of the apiary. Nonetheless, based on honeybee collected pollen, both trees and shrubs were used extensively during the early-season along with many other plants that belonged to 20 different families. The family Oleaceae or the olive family which consists primarily of trees and shrubs including both green ash and lilac made up nearly 50% of honeybee collected pollen during one week in May of 2021 which demonstrates how important pollen from flowering trees and shrubs can be during the early-season.

Honeybees require access to flowering plants to acquire both nectar and pollen which are needed for survival and colony growth. The early season is a time of limited floristic resources for honeybees and our results show that trees and shrubs can help fill the gap. Though our data suggests beekeepers may not see immediate colony growth with associating their colonies with shelterbelts, they will provide their bees with a critical food source during a time when other plants are not readily in bloom.

Landowners and managers should consider using a diversity of flowering trees and shrubs during future shelterbelt construction and refurbishing projects given their potential to provide honeybees with forage during the early-season. Likewise, beekeepers can provide forage for their bees by positioning their apiaries within feeding distance of shelterbelts. Future work should evaluate the flowering periods of other trees and shrubs available for use in shelterbelts in an effort to provide a longer period of time each spring when trees and shrubs are flowering and providing resources for honeybees and other pollinators.

Objective 1 - Quantify honeybee colony weights throughout the early-season (mid-May to early-July) to assess their relationship with trees and shrubs found in shelterbelts.

Objective 2 - Evaluate use of trees and shrubs as forage by honeybees during the early-season using honeybee collected pollen.

Objective 3 - Educate stakeholders about the importance of pollinators including honeybees which are critical to food production in the United States.

Stakeholders:

- Private landowners interested in pollinators or shelterbelts

- Beekeepers

- Soil Conservation Districts

- United States Department of Agriculture (Farm Service Agency, Natural Resource Conservation Service)

- Students

- Ag. Educators

- Scientist

Learning outcomes:

- Understand how shelterbelt abundance (Objective 1) and composition (Objective 2) boosts honey production and honey bee colony growth

- Increase awareness about pollinators, their ecology, and how shelterbelt management can improve their health (Objective 3)

Action outcomes:

- Beekeepers will select more productive early-season landscapes and produce a larger honey crop

- SCDs will promote cost-effective flowering trees and shrubs in shelterbelts that benefit pollinators

- Landowners will benefit from greater crop and forage pollination because of future pollinator-friendly shelterbelts

Globally, native and managed pollinators are experiencing broad-scale population declines, causing a reduction in available pollination services (Council et al., 2007; Potts et al., 2010). Pollinators, however, are extremely important for humans both economically and for global food security (Gallai et al., 2009; Klein et al., 2006; Potts et al., 2010).

Since the mid-1900s the U.S. Department of Agriculture has tracked and documented an overall decline in managed European honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies (Council et al., 2007). Similar to declines in other pollinators, factors including parasites, pests, and pathogens interact, weakening populations (Council et al., 2007; Potts et al., 2010). As the primary commercial pollinator in North America and the most widely used and managed pollinator in the world, declines prohibit the European honeybee population from keeping up with the demand for their pollination services (Aizen & Harder, 2009; Delaplane and Mayer, 2000; Kearns et al., 1998; McGregor, 1976).

In the U.S. annually, honeybee pollination is estimated to be valued between $1.5-18.9 billion (Council et al., 2007). In 2019 alone, 157 million pounds of honey were produced with a honey production value of over $309 million ("U.S. Honey Industry Report - 2019," 2020).

In addition to their importance throughout the US, honeybees are an important species for the Northern Great Plains (NGP) region. After a mass transport of honeybee colonies back to the region in early spring, the Northern Great Plains region hosts about one million honeybee colonies, leading the country in honey production and making honeybee declines particularly concerning (Otto et al., 2016; "U.S. Honey Industry Report - 2019," 2020).

Increasingly, land-use change reduces forage availability for honeybees throughout the year and influences their survivorship (Smart et al., 2016). These changes limit forage and nutrient diversity necessary for honeybee survival, and colony growth (Smart et al., 2016).

One potential solution to lessen future declines in honeybees is to promote forage diversity specifically at times when it is lacking (Decourtye et al., 2010; Dolezal et al., 2019). Early spring floral resources are often limited in grasslands, however, and flowering trees and shrubs could fill this niche and provide crucial resources in a time of need for declining honeybee populations.

Around the world, trees and shrubs have been highly documented as important honeybee resources especially during spring (Brodschneider et al., 2019; Lau et al., 2019; Sponsler et al., 2020). Tree and shrub plantings in the NGP are commonly known as shelterbelts, and were originally planted to provide soil stability and windbreaks, although they provide numerous services for human use (Gardner, 2009; Johnson & Beck, 1988).

The goal of our study is to determine if early flowering trees and shrubs planted in the NGP provide essential resources to fill early-season forage gaps for honeybees.

Cooperators

Research

Apiaries with a greater area of shelterbelts within a 1-mile radius will experience greater colony weight gains relative to colonies belonging to apiaries located in areas with less cover of shelterbelts.

Honeybees will use trees and shrubs associated with shelterbelts as pollen sources to a greater extent early in the growing season relative to other forbs on the landscape.

We conducted research in Central North Dakota near the Central Grasslands Research Extension Center in 2020 and western North Dakota near the Hettinger Research Extension Center in 2020-2023. Research was done on private and public lands using commercially owned honeybee colonies. We monitored honeybee colonies in Adams, Grant, Stutsman and Kidder Counties in North Dakota and in Perkins County, South Dakota. Bees owned and managed by Browning Honey Company (Central ND) and T2 Honey Company (Western ND) began arriving in North Dakota around mid-May.

Prior to honeybee arrival, we uploaded potential apiary locations into ArcGIS and overlaid points on a North Dakota Forest Service tree cover layer. We used these data to determine the proportion of trees cover that occurred within a 1-mile radius of each apiary. We than selected apiaries (research sites) at central and western locations that covered a range of tree cover in proximity to apiaries.

To assess the growth of our bee colonies, we fit two colonies per location (apiary) with digital scales. Scale data was used to determine how colony growth varies across our shelterbelt gradient. Colony weights are automatically recorded and saved every 60 minutes throughout the duration of our study. Two additional colonies per location were fitted with pollen traps that collect pollen from bees as they returned from foraging. Colonies within apiaries used for research were checked prior to the onset of research to ensure a healthy queen was present. Pollen traps were opened every five days for two consecutive days from mid-May to mid-July while most trees and shrubs were flowering. We labeled collected pollen and froze for future preparation.

We cleaned, dried, and ground 10 g of each pollen sample into a homogenized powder and returned the extra pollen to the freezer. Following pollen processing, 10 g samples were sent to a USGS lab for floral family/species identification. Pollen in some instances was identified to species, but most frequently pollen was identified to the family level.

Vegetation Surveys

We further classified tree rows (clusters of more than 2 individual plants of typically one tree or shrub species) that fell within a one-mile radius of each apiary. Mapping included species types, individual counts, and geographic locations. Following site classification, we conducted weekly drive-by surveys throughout the season at each site. During weekly surveys, we categorized tree and shrub rows by average floral resource percent flowering categories. We compiled these data to document species phenology by region and to record nearby tree and shrub composition.

We monitored colonies at 17 apiaries in western North Dakota in 2022 for a project total of 268 honey bee colonies at 68 apiary sites over three years (24 sites in 2020, 27 sites in 2021, and 17 sites in 2022).

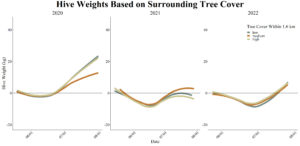

Hive Scales

We assessed changes in colony weights using hourly scale data for all colonies across all years . We began by subtracting the appropriate weights for days when the bees were fed or precipitation resulted in a dramatic increase in hive weights due to absorption. We also accounted for days when supers were added and subtracted. These subtractions allowed us to more closely monitor honey bee colony growth and honey production across sites and colonies. Using three years of weight data, results suggest that trends in seasonal hive weights varied between years (Figure 1). On average, colonies lost weight the first weeks they were monitored and gained weight the last few weeks. Overall, colonies gained more weight during 2020, with colonies gaining less weight in 2021 and 2022 field seasons. When hive weights were compared with tree cover surrounding sites, we did not find a significant difference in hive weights based on area of tree cover within 1.6 km buffer distances from sites (Figure 2).

Pollen Collection

We identified to family the pollen samples collected in 2020 and 2021. Honey bees collected pollen from a variety of plant families (Figure 3). Early season pollen collected by bees in 2020 in the Central region included 18 plant families across the sample period. Honey bees collected high concentrations of pollen from Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Fabaceae, and Salicaceae families. Moderate to high pollen quantities were collected from Oleaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Rosaceae families. Cannabaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Elaeagnaceae, Oleaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, Salicaceae, and Sapindaceae families have shelterbelt species and were found in 2020 pollen from the Central region. Pollen collected in 2020 in the Western region included 20 families. High concentrations of Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Fabaceae, and Oleaceae families were found across pollen samples. Rosaceae and Salicaceae families were found in moderate to high concentrations. Honey bees collected pollen from Caprifoliaceae, Elaeagnaceae, Oleaceae, Pinaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, Salicaceae, and Sapindaceae shelterbelt families at Western sites in 2020. The 2021 pollen from the Western region included 18 plant families. Honey bees collected high concentrations of pollen from Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Fabaceae, Oleaceae, and Poaceae families and moderate concentrations of Rosaceae pollen. Pollen from shelterbelts came from Caprifoliaceae, Elaeagnaceae, Oleaceae, Pinaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, Salicaceae, and Sapindaceae families.

Shelterbelt Composition and Floral Phenology

We visually quantified the flowering dates of flowering trees and shrubs within shelterbelts from 2020-2022. Shelterbelts near colonies varied in size and richness of species used during establishment. In 2020 we monitored 9 shelterbelts that averaged 7 flowering trees or shrub species per site and ranged between 3-9 different species per shelterbelt. In 2021 we monitored 27 shelterbelts. The species richness of flowering trees and shrubs per shelterbelt averaged 9 and ranged from 3-23. We monitored 15 shelterbelts in 2022 which averaged 9 unique flowering tree or shrub species per site with richness ranging from 3-21 species per site. The number of individuals per species also varied across sites and ranged from 5 to 2,500. For example, one shelterbelt had a short row that consisted of 4 amur maple, and a long row that consisted of 581 individual lilacs.

Green ash, caragana, common chokecherry, lilac and Russian olive were among the most common trees/shrubs observed in shelterbelts. The majority of these species bloomed in mid-late May through early July (Figure 4;Tree_shrub Phenology). While most species were done flowering by the middle of June, Russian olive flowered well into early July.

The amount of pollen collected directly from trees and shrubs was difficult to assess for some species given we could often only identify pollen to the family level. However, there are some families that we identified pollen from that are composed primarily of flowering trees and shrubs such as Oleaceae which include both green ash and lilac and Elaeagnaceae which included Russian olive. Between 10% and 50% of honeybee collected pollen belonged to species from the Oleaceae family in late-May which corresponds most years with the ash and lilac bloom (Figure 5;Figure 5_Oleaceae Pollen and bloom periods). On average, honeybees collected pollen samples contained less than 10% Russian olive pollen, with bees using pollen from Russian olive from mid to late-June (Figure 6_).

Our findings support earlier research that has demonstrated the great variety of plant species honeybees use as forage. During the early season, which for this study we classified as mid-May to the first week in July, honeybees collected pollen from plants belonging to 20 different families. These finding suggests the importance of maintaining plant diversity in agricultural landscapes.

We quantified honeybee colony growth during the early-season based on the proportion of shelterbelt cover surrounding each colony and found that overall the amount of shelterbelt cover surrounding colonies did not influence colony growth. We worked to isolate colony growth, by removing weight related to honey production, equipment additions, and climatic factors such as rain. Perhaps our findings would have been different if we included weight gains associated with honey as honeybees may have compensated for unseen benefits associated with surrounding trees/shrubs during honey production. We intend to take a closer look at this relationship in the future.

Though our early analyses suggests the amount of shelterbelts surrounding a colony does not influence honeybee weight gains, pollen samples collected by honeybees do suggest they frequently forage on trees and shrubs associated with shelterbelts in the North Central Region of SARE. In fact, of the 20 families for which we identified bees foraging on through pollen samples, at least nine contained species that were classified as either trees or shrubs. Our study shows that pollen belonging to trees and shrubs were important for honeybees during the early-season with over 50% of some pollen samples belonging to families made up almost entirely of trees and shrubs. Trees and shrubs that may be of particular interest to bees based on pollen samples include ash, lilac, willow, honeysuckle, buckthorn, Russian olive, chokecherry and plum.

The goal of our research was to evaluate the use and relationship between domesticated honeybees and trees and shrubs used in shelterbelts in the NCR. While our early analyses did not find any relationship between honeybee colony growth and shelterbelts, our pollen results do demonstrate their use by honeybees during the early-season. The early season is a time of limited floristic resources for honeybees and our results show that trees and shrubs can help fill the gap. New shelterbelts are made annually throughout the North Central Region of SARE and existing ones refurbished. Private landowners and county/state/federal land managers should plan to include flowering trees and shrubs during shelterbelt construction and management in an effort to provide additional early-season resources to honeybees and other pollinators. In our region of the NCR, the majority of trees and shrubs flowered at the same time which likely produced a needed boost of resources for bees that didn't last as long as it could have if other species were included with slightly different flowering periods. In our area, Russian olive flowered later than most other trees and shrubs we monitored and provided honeybees with additional resources towards the end of the early-season. Managers should evaluate the flowering period of other species used in shelterbelts in an effort to provide a longer array of early-season resources for honeybees associated with flowering trees and shrubs.

Trees and shrubs associated with shelterbelts can provide critical early-season resources for honeybees in the NCR. Though our data suggests beekeepers may not see immediate colony growth with associating their colonies with shelterbelts, they will provide their bees with a critical food source during a time when other plants are not readily in bloom.

Education

Our research team hired Hailey Keen as the graduate student responsible for this project. She played a critical role in the research and outreach associated with this project. We were able to learn all about the honeybee industry as a team, through hands-on experience. In addition to Hailey and the rest of the team, we also hired six summer technician who worked closely with the team during research activities.

We have engaged beekeepers, private landowners including farmers, students and land managers about our projects and findings. We have also kept other scientists updated on the project through presentations and posters.

Project Activities

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

We provided a synopsis of the project to be published in the ND Department of Agriculture for their Apiary Newsletter.

In 2021, we began to more actively engage the public and colleagues regarding our research. We provided an introduction/update of our project by presenting preliminary findings at the Society for Range Management in February 2021 , presenting to the advisory board in summer 2021, , and outlined the project at a wildlife workshop at the Hettinger REC in October of 2021. As previously mentioned, we visited with student in a first grade class about honeybees and beekeeping, focusing on their biology and needs from the environment.

We worked with NDSU extension to create a short youtube video that outlines the project and can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jOWaQ-DChLA

We presented our findings to the ND Association of Soil Conservation Districts and the ND Bee Keepers Association in 2022. The information was well received and we had many comments and conversations based on the data. We also had the opportunity to present at the North Dakota State University Fall Conference for Extension and Research Extension Center. This crowed primarily consisted of Ag. Educators. Perhaps the highlight of outreach for the year is when we teamed with Adams County Extension, Pheasants Forever and the Hettinger Elementary School to establish a pollinator garden at our local lake near the walking path. Along with planting the garden, we also talked all things pollinators including a good discussion on honey bees. A few of the student even opted to climb in the bee suit!

We have continued to use our pollinator garden to educate students at local public schools about pollinators and the importance of maintaining plant diversity on agricultural landscapes. In fall 2023, several students from the local school visited the garden and we conducted pollinator and plant surveys to demonstrate all the different insects that were currently using the small plot.

We have continued to share our information at professional conferences. A few of the presentations have been attached above.

Two journal articles in preparation:

Keen et al. 20XX. Early-season floristic resource use by honeybees in the Northern Great Plains.

Keen et al. 20XX. Honeybee weight gains during the early-season and the implications for land use.

Learning Outcomes

- Honey bee biology and habitat use

- Importance of flowering resources for pollinators

- Importance of the honey bee industry to our state

- Tasks of a bee keeper

- Shelterbelts species used for pollen by honey bees

Project Outcomes

local landowners who will include flowering trees and shrubs in upcoming shelterbelt establishment or management