Progress report for LNC22-463

Project Information

Title: Exploration of Shredded Cardboard as a Mulch to Improve Plant and Soil Health in Urban Farms and Gardens in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, MN

Problem Description: Mulching is utilized by urban growers to build soil health, mitigate weed pressure, and reduce water use. Despite these benefits, many mulching materials have become too expensive for growers to purchase and transport in the quantities required for an urban garden or farm. Our community-university research team identified shredded cardboard as a potential new mulch material that is accessible and affordable because of the increase in cardboard packaging for home delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. The overall objective of this collaborative project is to assess the performance of shredded cardboard mulch in urban farms and gardens.

Key Outcomes: Researchers, extension educators, and urban growers will increase understanding about the efficacy of shredded cardboard mulch and its impact on plant health, water use, and soil fertility. Researchers/educators will leverage grower experiences to develop mulching guidance and education resources. Growers will implement mulching practices to increase yields while stewarding environmental resources, such as water and soil nutrients.

Approach: Activities were designed collaboratively by the community-university research team and informed by feedback from twenty growers who participated in a pilot study of shredded cardboard mulch in summer 2021. Growers observed that while mulch reduced weed pressure and maintained soil moisture, crops were more susceptible to chlorosis (leaf yellowing). Thus, we will conduct replicated research trials at the University of Minnesota to compare the effects of shredded cardboard mulch, straw, and no mulch on yield; nitrogen cycling; and soil characteristics (Activity 1). Based on grower interest in conducting research and requests for support to implement mulching, irrigation, and fertility management practices, we will facilitate complementary grower trials at six community gardens and facilitate co-learning gatherings to build shared knowledge (Activity 2). Finally, we will connect shredded cardboard mulching practices to broader environmental justice and climate change adaptation efforts by establishing an industry advisory panel, conducting a literature review, and facilitating three tours per year of sites such as cardboard production, recycling, and composting facilities, garden networks, or community organizations addressing climate change (Activity 3).

Relevance: In combination with parallel projects to explore local production and distribution of shredded cardboard, this project will contribute to increasing the availability, affordability, and accessibility of a new mulching option, which would benefit small-scale growers throughout the North Central Region.

Researchers, extension educators, and urban growers will increase understanding about the efficacy of shredded cardboard mulch and its impact on plant health, water use, and soil fertility. Co-learning gatherings will deepen relationships between researchers and growers; build shared knowledge; and increase grower capacity, all of which will support action outcomes (people). Researchers/educators will leverage grower experiences to develop mulching guidance and education resources. Growers will implement mulching practices to increase yields (profitability) while stewarding environmental resources, such as water and soil nutrients (planet). Participating in tours will highlight connections between research, grower practices, environmental justice, and climate change.

Background:Urban Agriculture in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, MN

According to the USDA, there are ~112,000 farmers in Minnesota – but urban farmers and gardeners are not included in this count (Recknagel et al., 2016; USDA Economic Research Service, 2022). Data collected by cities and community organizations indicate that, as of 2016, there were at least 20 farms, over 600 community gardens, and innumerable backyard gardens in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area (TCMA) (Prather, 2016). Even a relatively conservative estimate of 20 growers per community garden (some have over 200 gardeners) would mean there are over 12,000 growers in MN, beyond those officially counted by the USDA. These growers have a significant impact on food production; an ongoing study conducted by one of our community-university research team members, Extension Educator Karl Hakanson, has found average yields from an urban garden are 70% higher than small- and medium-scale vegetable farms in rural areas (~0.85 lbs./sq. ft. and ~0.5 lbs./sq. ft, respectively) (Hakanson & Straub, 2020; Rabin et al., 2012). Food production in urban agriculture (UA), however, is pursued as part of broader social and ecological goals. Urban growers – especially those from Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized communities – leverage UA to imagine and create relationships with land, people, and food that address systemic challenges (such as climate change and environmental justice), build community connections, and repair ecological relationships (Cadieux & Slocum, 2015). A prior NCR-SARE project (LNC17-392) conducted by our community-university research team found that common UA practices like amending soil with compost builds soil carbon, supports complex insect communities, and increases water infiltration, all of which were achieved in farms and gardens simultaneously conducting youth education, facilitating mutual aid networks, and more (Nicklay et al., 2019). Urban farms and gardens can more effectively enact these multifunctional goals when growers have consistent and affordable access to resources such as land, networks to learn and share knowledge, water, tools, and soil amendments. Each member of our community- university research team conducts work that supports systemic strategies to address these varied resource needs, and we came together in this project to specifically focus on developing an affordable, accessible, and locally-produced mulch.

Mulching to support food production, soil health, and climate change adaptation

The benefits of horticultural mulch are well established. Many plant-based materials are used as mulch, including straw, corn stalks, wood chips, coir, leaves, paper, pine needles and cardboard; these organic mulches mulches suppress weeds, reduce labor needs and water use, protect plants from pests / diseases, and build soil carbon (Iqbal et al., 2020). Depending on history and location, gardens may require such interventions to support food production and other ecosystem services because urban soils are often affected by contamination, erosion, compaction, and invasive weeds. Organic mulches are also an important resource to maintain high yields as growers adapt to climate change. Minnesota will likely be affected by longer, more frequent droughts interspersed with heavy rainfall events (Hubbard, 2021). Mulches can help growers adapt by increasing water infiltration, which helps reduce pooling and runoff during heavy rainfall, and increasing soil moisture retention, which improves irrigation/rainfall use efficiency by plants (Pavlů et al., 2021). Mulch can also help protect plants as warming temperatures bring new invasive pests to MN (Moss et al., 2013). It is important to note that the impacts of climate change are *not* distributed equally; systemic, environmental racism in urban planning and development mean that Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color are more likely to experience air pollution from polluting industries, higher temperatures due to reduced green space, flooding due to poorly maintained stormwater management infrastructure (citation). Mulching, alone, cannot address these systemic problems – but mulching does represent an important way for urban growers to mitigate their impacts and, when mulching resources and practices are developed in community, represent an opportunity to build shared knowledge (and capacity for collective action) at the intersection of urban agriculture, climate change, and environmental justice.

Need: Affordable, accessible mulch options for urban farms and gardens

Despite these benefits, urban farms and gardens are facing increasing obstacles to source adequate, affordable supplies of mulch and compost materials. We hear from urban growers – at farm tours, over zoom meetings, and in phone conversations – that many mulching materials have become cost prohibitive for growers to purchase and transport in the quantities required for an urban garden or farm. Many growers – especially backyard and community gardeners – do not have space to store leaves over the winter to use as mulch the next season. Many avoid plastic mulches because, though less expensive, they are non-recyclable, which does not align with the environmental values that motivate many growers (citation). While there are some city and county programs to access free or reduced-cost compost, there are no similar programs in TCMA for mulches like wood chips or straw. Wood waste is increasingly used for energy production and large-scale municipal mulching (Greinert et al., 2019). Grain straw has become more costly as interest in techniques like straw bale gardening increases, and urban growers often either lack relationships with rural grain producers or the means to transport straw purchased directly from rural producers. Finally, emerging concerns about spreading invasive jumping worms in organic materials, like mulch, are adding to the tightened resources (Gupta & Van Riper, 2021). To address this need, Stephanie Hankerson (grower and garden educator), Melvin Giles (elder and Urban Farm and Garden Alliance - UFGA - co-coordinator), and Karl Hakanson (Extension educator) began imagining creative approaches to mulches.

Grower-led explorations of shredded cardboard mulch

Hankerson, Giles, and Hakanson identified shredded cardboard as a potential option for affordable and accessible mulch – that could also be produced locally. Cardboard is already often used in urban farms and gardens for sheet mulching, in which growers build beds by laying cardboard on the soil and then adding compost and top soil on top. A past SARE farmer/rancher project in Massachusetts (FNE10-677) found that cardboard sheet mulching resulted in the most stable and consistent soil moisture and temperature throughout the growing season compared to other treatments (straw mulch, newsprint mulch, and bare soil) and was equally as effective at weed suppression. Ongoing farmer projects in Idaho (FW22-393) and Guam (FW19-348) are also the impacts of cardboard sheet mulching on weed suppression, soil quality, and labor. The farmer in Guam specifically notes that they are utilizing cardboard because high imports create significant cardboard waste, which is sent to landfills. This is similar to Hankerson, Giles, and Hakanson’s observations during their initial conversations in 2020; they observed that increased reliance on door-to-door shipping services during the COVID-19 pandemic greatly increased the amount of corrugated shipping boxes delivered to residences and commercial warehouses. Only about 50% of cardboard is recovered in residential recycling (Foth Infrastructure & Environment, LLC et al., 2016; Hennepin County Environment and Energy, 2021), and residential recycling and waste industries -- through working conditions and site placement -- both disproportionately harm communities that are predominantly Black, Indigenous, or other people of color (Pellow, 2004). Using cardboard as a mulch, therefore, seemed like a win-win: cardboard was an abundant neighborhood resource that could improve grower access to mulch while reducing waste.

However, Hankerson, Giles, and Hakanson had concerns about using cardboard sheets around plants and on top of the soil. Cutting the sheets to fit between rows would be labor intensive and, if growers were utilizing intercropping or square-foot gardening practices, unrealistic. They were also concerned solid sheets could change water flow and impede infiltration. Shredded cardboard, however, would be similar to straw or wood chips in ease of application around plants. Inspired by a grower in their network who constructs garden beds from just shredded leaves (amended with nitrogen fertilizers), they wondered if shredded cardboard mulch was a viable strategy. In early 2021, they approached university extension educator/researcher Mary Rogers and graduate student Jennifer Nicklay (relationships established through our past NCR- SARE grant LNC17-392) with the idea to use cardboard as a garden resource.

Our community-university research team planned and implemented a pilot study in summer 2021 to explore the feasibility of using shredded cardboard in gardens. We recruited over 20 growers from across the TCMA – including farmers, community gardeners, and backyard gardeners – and provided them with free shredded cardboard Hakanson purchased from Western Resources Group (www.nebraskawrg.org) in Nebraska. In partnership with the series of Community Land and Food Gatherings facilitated by Nicklay (funded by a University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment Impact Goals Grant), we held a co-learning gathering for UFGA growers to share their experiences with mulch and their questions, such as how mulch impacted yield or soil moisture and what strategies growers could use to track such characteristics without specialized equipment. Based on these insights, we developed a feedback form that growers completed in July and October to share their observations, feedback, and experiences with the shredded cardboard mulch. Growers reported that they like the idea of creating a sustainable source of mulch and saw that weeds were less prevalent while soil moisture seemed higher (by touch) with the cardboard mulch than with other mulch types or in areas without mulch. In general, plants cultivated with cardboard mulch grew as well as those with other mulches but some issues were reported, including some plants with stunted and yellowing foliage (likely chlorosis due to nitrogen availability) when cardboard mulch was applied around small seedlings or mixed with the soil. From these experiences, we learned that further research is needed to develop guidance around plant health, water use, and soil fertility / nitrogen cycling.

Research

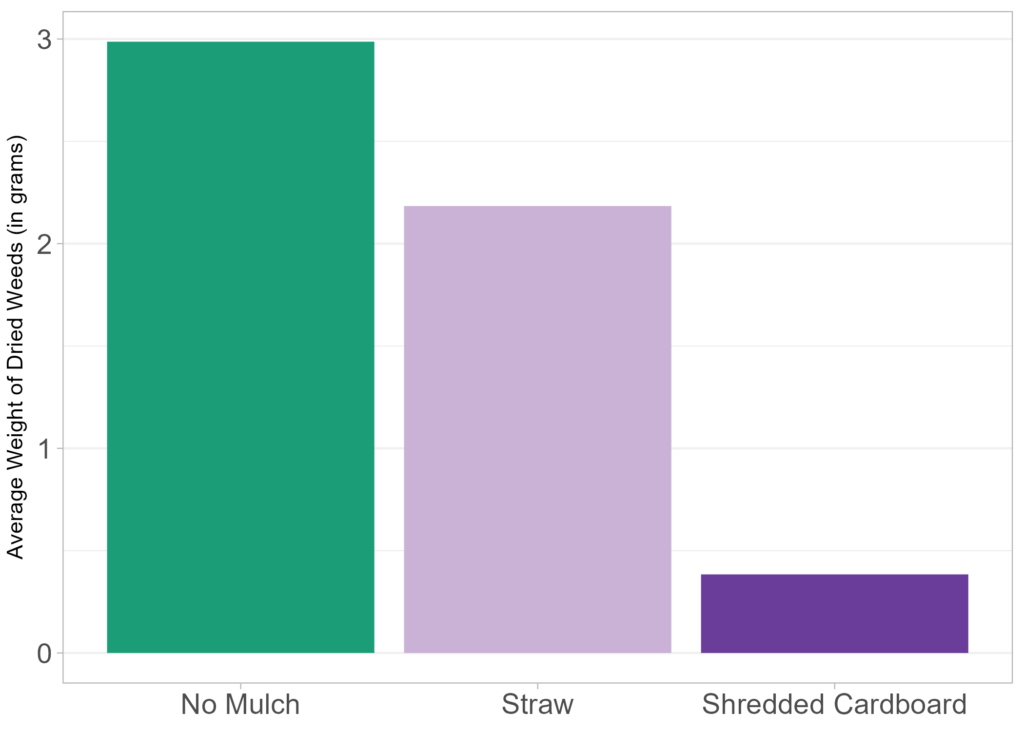

We hypothesize that shredded cardboard mulch will result in increased soil water content, decreased weed biomass and time spent weeding and increased marketable yield relative to straw mulch and bare soil treatments. We hypothesize that shredded cardboard mulch will result in decreased plant available nitrogen relative to bare soil treatments, but increased plant available nitrogen relative to straw mulch treatments.

We propose three activities to integrate research, co-learning, and outreach: 1) assess performance of shredded cardboard mulch; 2) build shared knowledge with urban growers, and 3) connect on-farm practices to broader systems. These activities build grower wealth by leveraging mulch to increase yield and reduce expenses (increasing profitability) while positively impacting ecosystem processes like nutrient and water cycling (protecting land/water). We utilize a co-learning framework developed in our previous NCR-SARE project (LNC17-392) to build/deepen relationships (enhancing quality of life for people/communities).

Activity 1: Assess performance of shredded cardboard mulch in annual horticultural cropping systems

Two research questions will be investigated: 1a) what is the effect of shredded cardboard mulch on within-season crop productivity? and 1b) what is the effect of shredded cardboard on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics? Research will be conducted at the UMN St. Paul campus and investigate three treatments: shredded cardboard mulch, standard straw-based mulch, and bare soil, hand-weeded control plot. Treatments will be applied to three annual crops: tomatoes, collard greens, and day-neutral strawberries in a randomized complete block design. Each mulch*crop treatment will be replicated four times. Each block will consist of 3 randomized mulch treatment rows (60’ in length) on 4’ centers. Plots will be randomized within each treatment row (20’ in length) with one crop/plot (36 plots total). Each row will include dripline irrigation and supplementation with organic nutrient sources through a fertilizer injector as needed based on soil tests. We will follow standard recommendations for plant spacing. Tomatoes (‘Defiant’) and collards (‘Flash’) will be sown in the greenhouse and transplanted and bare root strawberry plants (‘Albion’) will be purchased from a commercial distributor. Soil will be prepared with a rototiller two weeks prior to planting in the spring (mid-May) and mulches will be applied directly after transplanting. The experiment will be terminated at the end of September and repeated over two years.

For 1a, we will take multiple measurements to assess the impacts of mulch treatment on crop productivity, including weed suppression; rhizosphere moisture and temperature; chlorophyll; fruit yield; and marketability of harvested produce. Weed density will be assessed by collecting aboveground weed biomass within a .25 m2 quadrate within each plot at 2 week intervals. Biomass will be dried, weighed, and compared across treatments. Weeds will be removed by hand and the time to do so will be recorded to determine weed labor hours. Flow meters will be used to record irrigation. Soil moisture and temperature sensors will allow us to assess the effects of mulch treatment on root zone environment conditions and water availability; however, these are expensive and will be placed within the center of tomato crop plots only (4 replicates). A SPAD meter will be used to measure crop nitrogen uptake. Foliar SPAD readings will take place on 3 randomly selected crops from the middle of each plot on fully developed new leaves from the top ⅓ of the crop canopy. Readings will be taken every 3 weeks to assess crop nitrogen across the growing season. Crops will be harvested twice/week when mature; yield will be measured as fresh weight and categorized into ‘marketable’ and ‘unmarketable’ classes based on USDA standards. Data will be collected from a ~10 ft section in the center of each plot to minimize edge effects. Tomatoes and strawberries will be picked vine ripe. Fully mature collard leaves (>4” in width) will be harvested with no more than ⅓ of the total plant biomass removed at each harvest period, to ensure continual harvests across the growing season. Cumulative crop yield across the growing season will be compared across mulch treatments to assess the impact of mulch type on crop yield.

For 1b, we will assess the effect of mulch treatment on soil carbon and several soil nitrogen pools. Total carbon and total nitrogen will be used to determine the soil C:N ratio, which is a broad indicator of how carbon is impacting nitrogen availability. We will also measure inorganic nitrogen (ammonium and nitrate), which represents the nitrogen that is plant-available at a specific moment, and potentially mineralizable nitrogen (PMN), which represents the organic nitrogen (largely from microbial biomass and plant tissue) that could become available to plants, depending on temperature, moisture, aeration, and time. To assess soil nitrogen availability across the growing season, we will measure carbon and nitrogen metrics at four sample points – planting, 3 weeks post-planting, 6 weeks post-planting, and final harvest. Eight random soil cores will be taken in each plot to a depth of 20cm and pooled (36 samples/sampling point, for a total of 144 soil samples/year). A fraction of each sample will be sieved to 2mm and stored at 4oC for PMN analysis within two weeks. The remaining soil will be air-dried and ground to 2mm for total carbon, total nitrogen, and plant-available nitrogen. At the end of year 1, we will use a split-plot design to study options for mulch incorporation. All plant biomass will be removed and the mulch treatments will either be incorporated into the soil by hand using a broad fork or removed prior to winter. Mulch treatments will be kept in place between years and crops will be randomized within these (to reflect the use of crop rotation); this design is important to develop recommendations regarding whether or not to allow mulches to decompose in place.

Activity 2: Build shared knowledge of mulching and related practices with urban growers

We will work with six growers in community gardens to establish grower trials of shredded cardboard mulch, supported by a series of co-learning gatherings at each garden to build grower capacity, support implementation of mulching practices, and create space for reciprocal sharing of knowledge/experiences between community gardeners and between growers and university researchers/extension educators. Grower trials and co-learning gatherings build on strategies used in the 2021 pilot project (see Background). The Community Programming Manager (Hankerson) and UFGA (Giles) have significant experience facilitating events and programs to support growers, and they will lead planning, coordination, and implementation for this activity. They will be supported by the graduate/undergraduate students and other members of our research team.

Grower Trials: Six growers in community gardens will be recruited through the community-university research team’s pre-existing networks. The six participating growers will receive a yearly stipend; ongoing support from Hankerson and the graduate student; and all necessary supplies, including shredded cardboard mulch, irrigation equipment, seedlings, recordkeeping journals, and scales. Each grower will use shredded cardboard mulch to cultivate at least one of the model crops (tomatoes, collards, or strawberries). Because past SARE-funded projects found that irrigation differences between garden trial sites significantly impacted results, we will work with growers to install irrigation equipment and flow meters at the beginning of Y1 to reduce variability in assessing the effects of mulch. Growers will use the flow meter to record their water use and crop yield in provided journals; Hankerson and the graduate student will train growers in measurement practices, which were previously developed in Jelinski’s USDA-NIFA (20196701930463-SUB0000375) and Hakanson’s Garden Productivity projects. Additionally, researchers will conduct soil nutrient testing (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) in the spring and fall each year, and Hankerson and the graduate student will support growers to interpret results and implement soil fertility practices, if needed. Buried soil temperature probes will record temperature, and the graduate student will measure soil moisture weekly. The quantitative measurements collected through the grower trials represent a subset of those in the research trials (Activity 1) and will be compared to results from the research trials. Analysis of results will be informed by grower experiences shared through a feedback form (developed for the pilot program) in July and September, through one-on-one conversations, and through co-learning gatherings.

Co-learning gatherings: A series of three co-learning gatherings will be developed each year, which will be offered at each of the six partner community gardens for 7-10 participants/gathering (for a total of 18 gatherings/year). This strategy of repeat visits at each garden intentionally focuses on building relationships between growers within a community garden. Hankerson and UFGA chose this strategy because, in their experience, co-learning is more effective with smaller groups of gardeners and because it is easier to manage COVID-19 safety precautions – especially to reduce risk for elders and immunocompromised growers.

Co-learning gatherings are layered and have multiple purposes, including cultivating relationships between growers, collecting data together, learning from multiple ways of knowing (e.g., ancestral, experiential, scientific), and building capacity for growers to implement practices with support from other gardeners and the research team. Gatherings will be about two hours long, with the 30 minutes dedicated for sharing food to facilitate relationship building; as one UFGA elder says, “there’s no meeting without eating!” We will recruit a paid guest community member (e.g., elder, artist, garden educator) to co-facilitate each gathering, which honors the knowledge already in our communities. Together, we will develop hands-on activities to practice practical/technical skills and facilitate interactions between growers, researchers, and educators to reciprocally share knowledge. The topics and activities for gatherings will be customized by gardens’ interests. Gatherings during year 1 will incorporate themes related to the grower trials, including the benefits of mulch, irrigation strategies to complement mulching, and recordkeeping strategies for growers to track the impacts of their practices across seasons. Gatherings during year 2 will incorporate connections between gardens and broader systems, such as utilizing land use history to interpret garden soil test results or identifying creative uses of novel mulch materials to explore waste/recycling industries. We will also discuss how practices relate to climate change adaptation and environmental justice, particularly focusing on insights from the literature review and tours in Activity 3.

Activity 3: Connect on-farm shredded cardboard mulch practices to broader systems

We will build shared knowledge around the interconnections between shredded cardboard mulch and broader systems of production, recycling, and waste; environmental justice efforts; and climate change adaptation. To achieve this goal, we will establish a 2-4 person industry advisory panel, conduct a literature review, and facilitate 3 tours/year, with 15-20 participants/tour.

Industry Advisory Panel: Our research team acknowledges that we currently don’t have expertise with bioproducts engineering, production, or recycling/composting industries for cardboard. We have connected with John Hafner at Westrock, a corrugated container manufacturer, and Jeff Standish, Industry & Government Liaison for MnDRIVE Environment at the UMN, both of whom will help us connect with relevant industry and government stakeholders to form an advisory panel. We will provide a stipend for panel members to meet quarterly with our research team to help us better understand industrial processes and identify opportunities to produce shredded cardboard locally.

Literature review: The graduate and undergraduate student will work together to conduct a literature review investigating cardboard production, recycling, composting, and disposal. In conjunction with the industry advisory panel, this is an important step to identify areas in the process where shredded cardboard could reduce waste.

Tours: Within UFGA specifically, and the TCMA urban agriculture community more broadly, there is a strong history of leveraging tours to cultivate connections and create foundations for collective action amongst people in different roles. We envision a great diversity of tour types, such as field days at our research plots, farm visits to rural growers, walking tours of urban garden networks, visits to community groups working on environmental justice initiatives, and industrial tours of cardboard (corrugated) recycling and manufacturing facilities. Tours are an opportunity to share stories, histories, obstacles, and resources across communities while breaking down barriers through in-person sharing and learning. Gardeners and farmers need technical information on cardboard production techniques and its impacts of climate change; employees of “institutions” (i.e, industry, higher education, municipal government) need information about how urban gardens and farms function; and participants in this study (growers and researchers) need information on how recycling industry and corrugated manufacturing operates. Together, we need to explore how locally producing shredded cardboard would impact environmental justice efforts to reduce the impact of waste industries and climate change on communities of color.

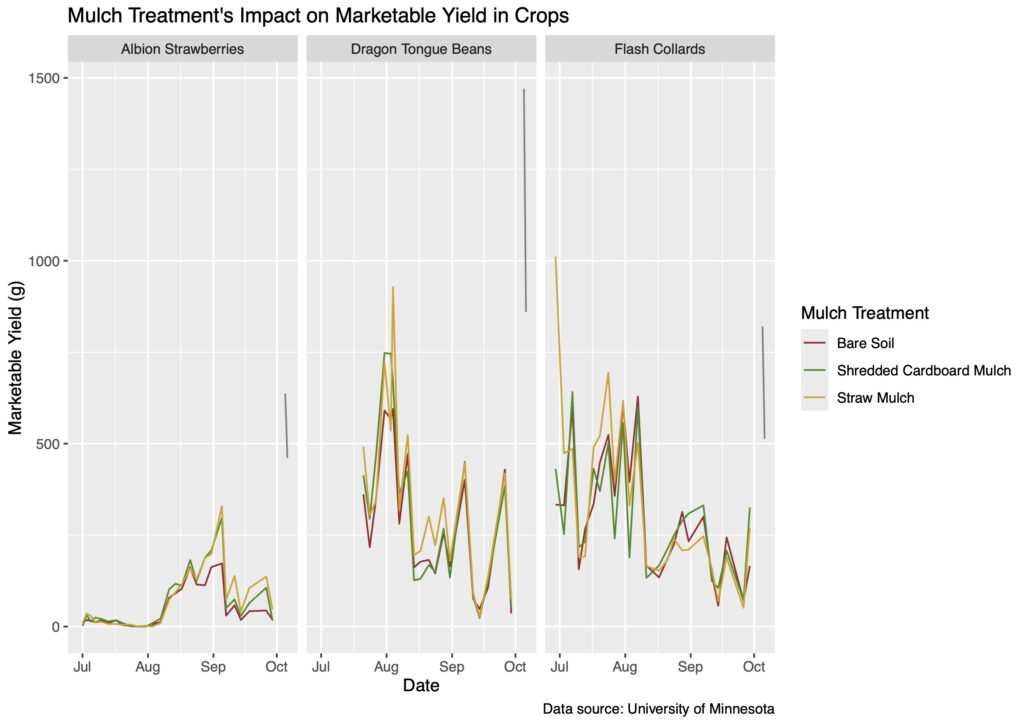

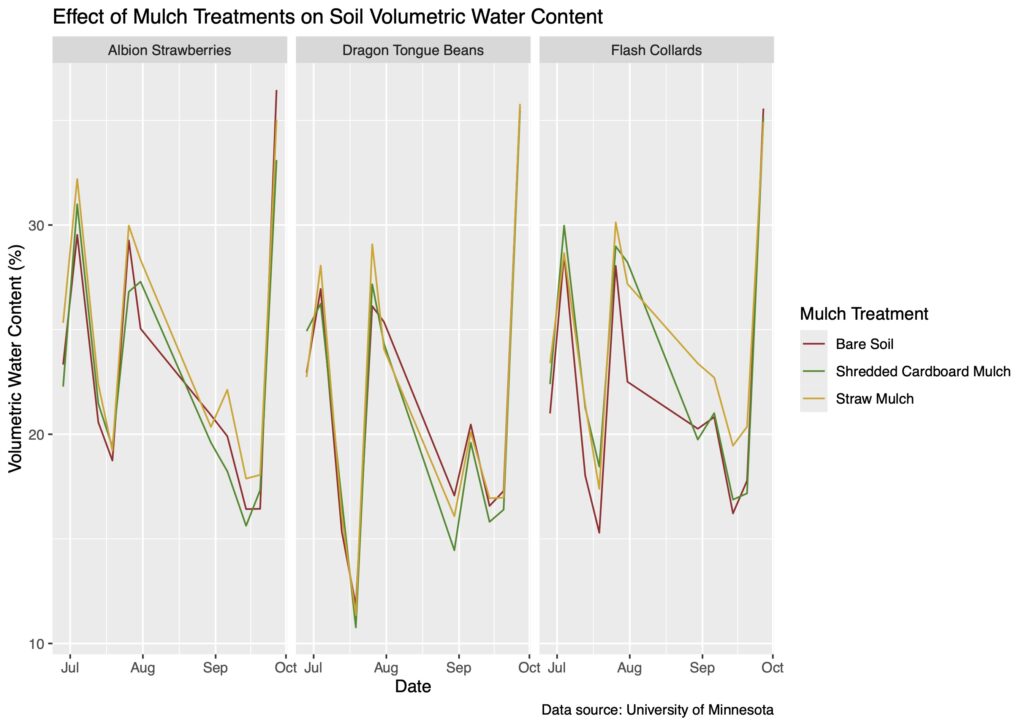

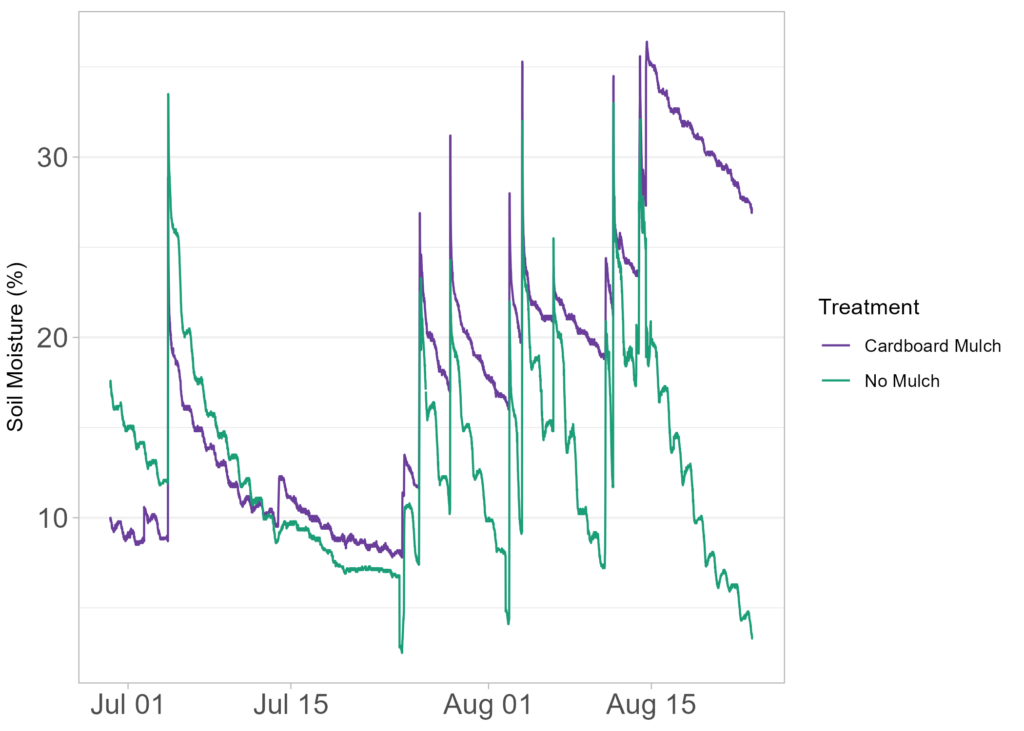

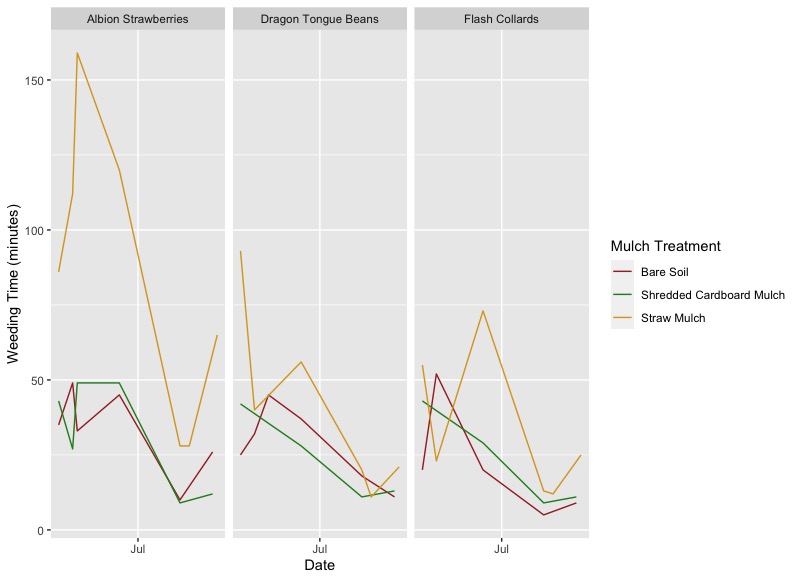

We are currently in the process of analyzing all data from 2023. Below are examples of preliminary results from the 2023 data for marketable yield, soil water content (volumetric), and weeding time. Tests for statistical significance will be conducted and incorporated into these analyses. Note that the first portion of the data presented is from replicated plots on the St. Paul Experiment Station at UMN, while the second portion is data, perceptions, and observations from grower surveys.

Summary of 2023 Preliminary Results:

- Shredded cardboard mulch had no significant impact on marketable yield (controlled, replicated)

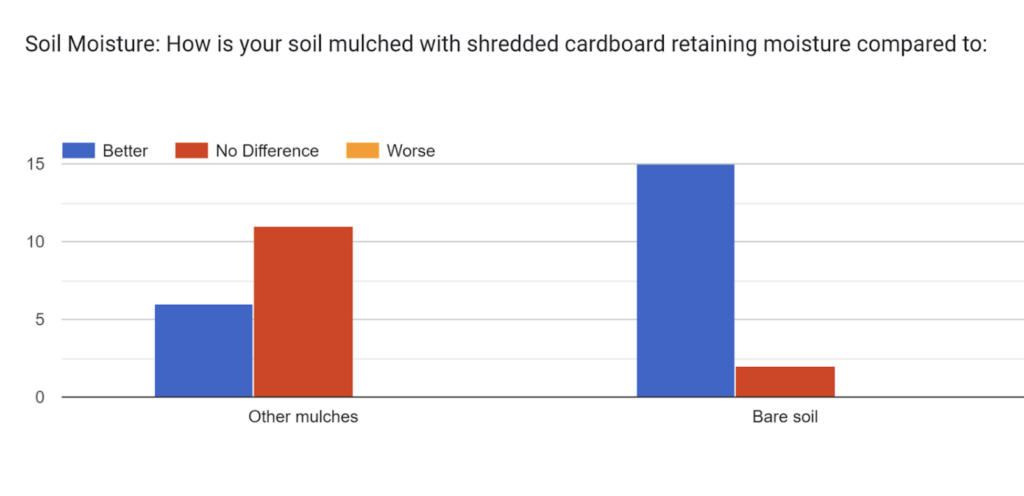

- Shredded cardboard mulch water content variable and not significantly different from other treatments (controlled, replicated, irrigated); shredded cardboard mulch led to significantly greater water content relative to bare soil (non-replicated community observation).

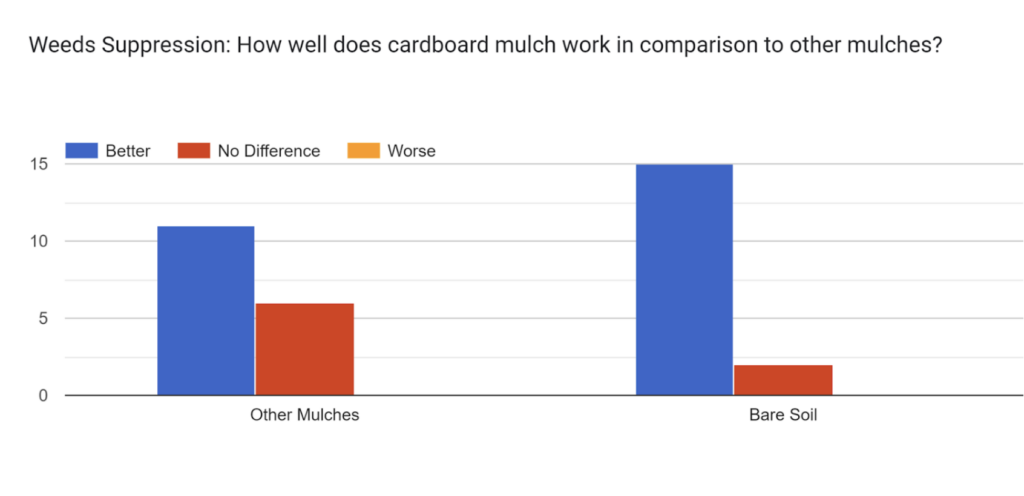

- Shredded cardboard mulch significantly reduced weeding time relative to straw mulch and bare soil (controlled + non-replicated community observation).

- Shredded cardboard mulch treatment resulted in numerically lower but not statistically significant difference in soil nitrate levels (controlled, replicated).

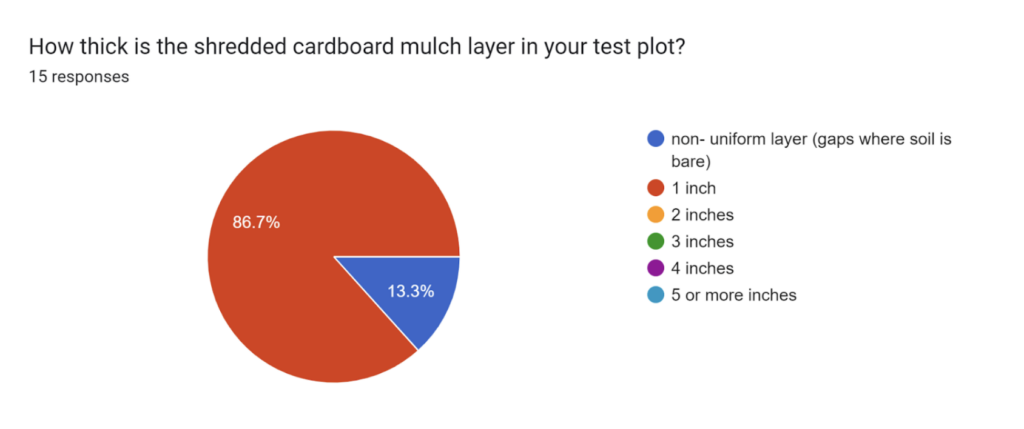

- Most growers applied ~ 1" of cardboard mulch to their plots (community observation).

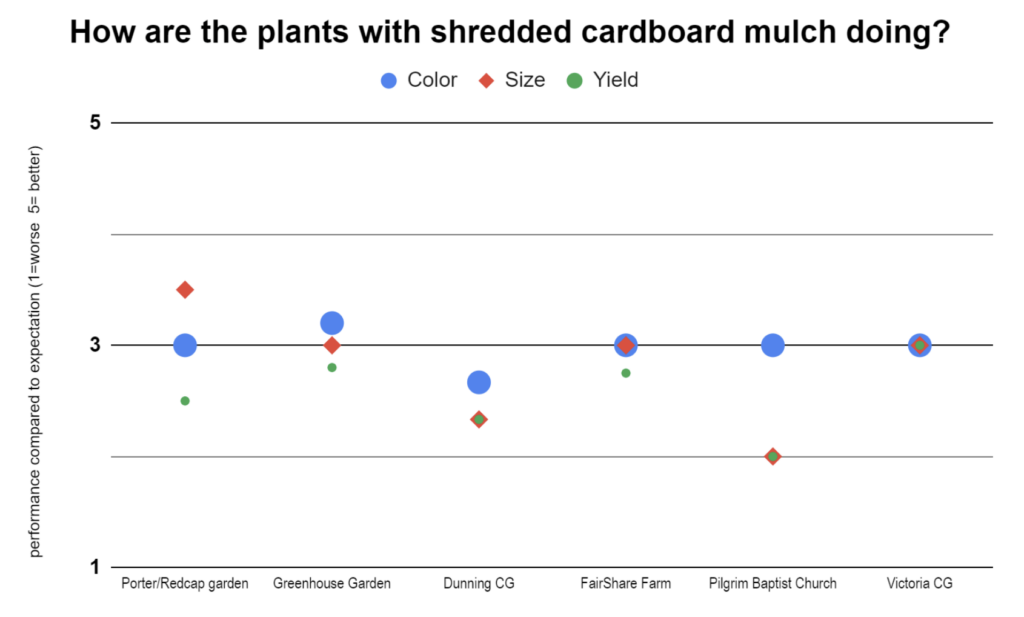

- Plants growing in shredded cardboard mulch treatments did not over or underperform relative to expectations (community observation).

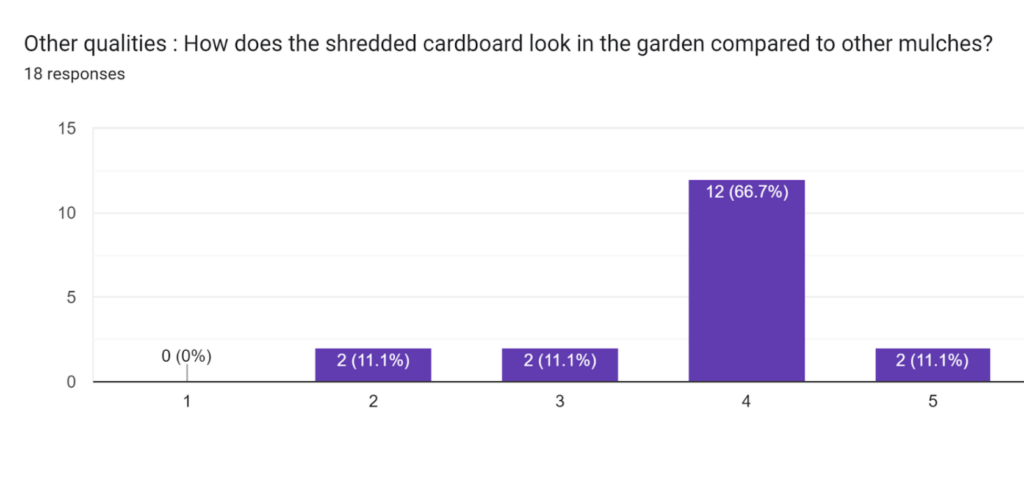

- Shredded cardboard mulch looks the same or better than other mulches (community observation).

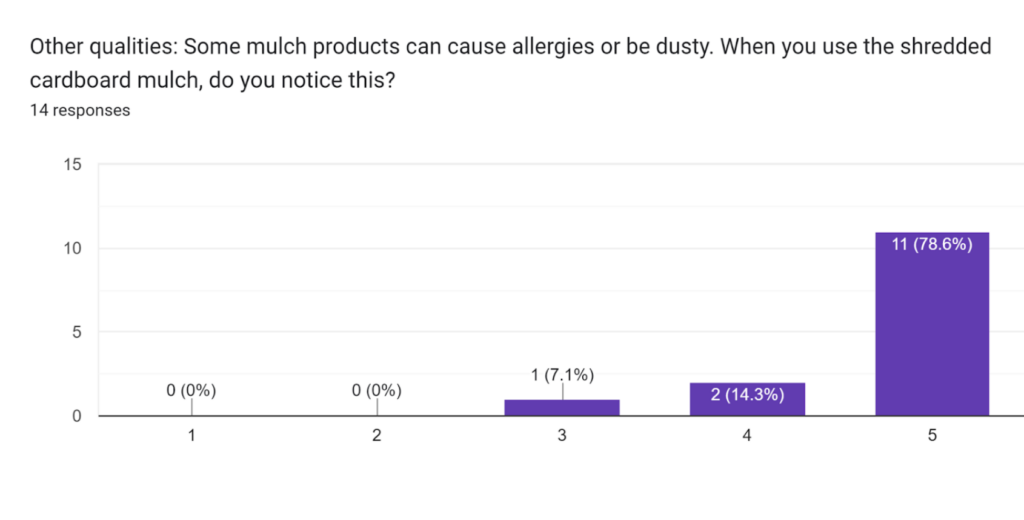

- Shredded cardboard mulch does not appear to be dusty or irritating, however moistening when laying down is recommended (community observation).

Marketable Yield:

For the 2023 data, time series analysis shows that both cardboard mulch and straw mulch appeared to have a significant impact on late season (August-October) strawberry yields relative to bare soil treatments but no major differences for other crops. Cumulative seasonal yields are currently being calculated and compared.

Soil Water Content

For the 2023 replicated plots on the St. Paul campus of UMN, time series analysis shows high variability across treatments and crops. In some cases it appears that shredded cardboard mulch may have resulted in similar or reduced water content relative to bare soil and straw mulch treatments. The mechanisms for this and statistical significance between treatments are being explored, however controlled plots at UMN were much more frequently irrigated than plots in community gardens.

Non-replicated plots in community gardens, however, showed clearer trends, with cardboard mulch treatments having higher coil moisture throughout the entire 2023 season. This effect became very apparent in later July and August, as the summer drought continued.

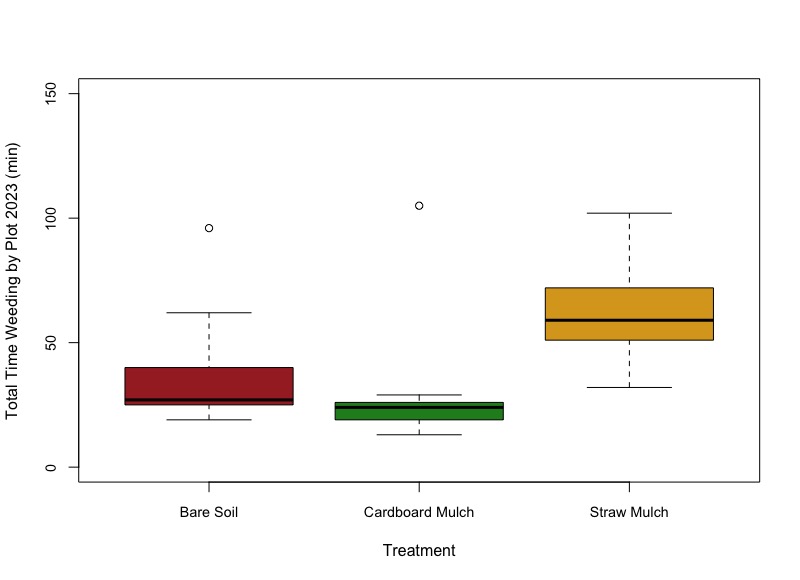

Weeding Time:

For the 2023 data, time series analysis shows that shredded cardboard mulch resulted in reduced weeding time relative to straw mulch and bare soil for strawberries and beans. Weeding time for shredded cardboard mulch treatments was similar to bare soil, but both were lower than straw mulch for collard greens. An analysis of total weeding time spent in 2023 by individual replicated plots shows that cardboard mulch resulted in significantly reduced weeding time compared to straw mulch and bare soil.

For a non-replicated community garden plot, this effect was numerically greater, however we have no way to test statistical significance in this observational case.

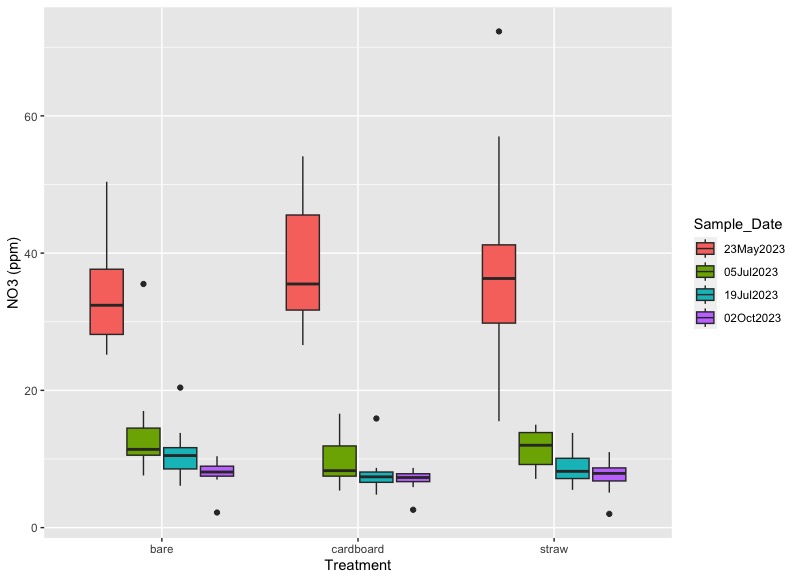

Plant Available Nitrogen:

Because shredded cardboard mulch has an extremely high C:N ratio, it has the potential to result in nitrogen immobilization. In the first year of the controlled experiments on the St. Paul campus, we observed numerically lower nitrate (NO3-) concentrations under shredded cardboard mulch, however these differences were not significant (Two-Way ANOVA w/ interaction (p > 0.1)) between bare soil, shredded cardboard mulch, and straw mulch treatments.

Grower Observations and Preferences:

“Tasty bites” for the worms?

Hypothesizing that with these smaller mulch pieces in shredded cardboard mulch rather than straw mulch or other mulch sources, that our mulch layer needs to be thicker or replenished over the season. Particularly where there is earthworm activity as the pieces seem small enough for the worms to move around. This is an observation not seen at the UMN field trial and demonstrates the usefulness of doing trials at farm and garden sites alongside the campus setting. It could be that earthworm populations vary from site to site and it has required the inclusion of 6 other locations in order to detect this. Incorporation of mulch into the soil is not an observation we have seen in earlier trials at community sites which utilized a larger shred. It follows that if earthworms are pulling cardboard into garden soils, then we might see competition for nitrogen showing up in plant health observations.

Recommendation: Refresh mulch midseason at CG sites if we use the same mulch source. Consider fertilizer application at that time too.

1 = worse, 3 = the same, 5 = better

1 = worse, 3 = the same, 5 = better

Education

We utilize a co-learning framework developed in our previous NCR-SARE project (LNC17-392) to build/deepen relationships between researchers, growers, educators and communities. Our educational co-learning approach is layered and addresses multiple goals, including cultivating relationships between growers, collecting data together, learning from multiple ways of knowing (e.g., ancestral, experiential, scientific), and building capacity for growers to implement practices with support from other gardeners and the research team. The activities that support this co-learning approach are grower trials (in garden/on farm), co-learning gatherings, tours and outreach events.

Grower Trials. To implement grower trials, six growers in community gardens will be recruited through the community-university research team’s pre-existing networks. The six participating growers will receive a yearly stipend; ongoing support from Hankerson and the graduate student; and all necessary supplies, including shredded cardboard mulch, irrigation equipment, seedlings, recordkeeping journals, and scales. Each grower will use shredded cardboard mulch to cultivate at least one of the model crops (tomatoes, collards, or strawberries). Because past SARE-funded projects found that irrigation differences between garden trial sites significantly impacted results, we will work with growers to install irrigation equipment and flow meters at the beginning of Y1 to reduce variability in assessing the effects of mulch.

Gatherings. Gatherings will be about two hours long, with the 30 minutes dedicated for sharing food to facilitate relationship building. We will recruit a paid guest community member (e.g., elder, artist, garden educator) to co-facilitate each gathering, which honors the knowledge already in our communities. Together, we will develop hands-on activities to practice practical/technical skills and facilitate interactions between growers, researchers, and educators to reciprocally share knowledge. The topics and activities for gatherings will be customized by gardens’ interests. Gatherings during year 1 will incorporate themes related to the grower trials, including the benefits of mulch, irrigation strategies to complement mulching, and recordkeeping strategies for growers to track the impacts of their practices across seasons. Gatherings during year 2 will incorporate connections between gardens and broader systems, such as utilizing land use history to interpret garden soil test results or identifying creative uses of novel mulch materials to explore waste/recycling industries.

Tours. Within UFGA specifically, and the TCMA urban agriculture community more broadly, there is a strong history of leveraging tours to cultivate connections and create foundations for collective action amongst people in different roles. We envision a great diversity of tour types, such as field days at our research plots, farm visits to rural growers, walking tours of urban garden networks, visits to community groups working on environmental justice initiatives, and industrial tours of cardboard (corrugated) recycling and manufacturing facilities. Tours are an opportunity to share stories, histories, obstacles, and resources across communities while breaking down barriers through in-person sharing and learning. Gardeners and farmers need technical information on cardboard production techniques and its impacts of climate change; employees of “institutions” (i.e, industry, higher education, municipal government) need information about how urban gardens and farms function; and participants in this study (growers and researchers) need information on how recycling industry and corrugated manufacturing operates.

Outreach. Our outreach strategy is grounded in building relationships throughout the project and aligns with the co-learning framework developed in our previous NCR-SARE project (LNC17-392). One-to-one relationships are cultivated through research team meetings, attending community meetings, and conversations shared during garden visits. Connections between groups of people learning together are facilitated through co-learning gatherings, where important information can be exchanged between growers. Tours build relationships between groups, creating the foundation for collective action across roles, locations, backgrounds, and identities. While traditional outreach is often imagined as a flow of information from the university to communities, our relational approach creates horizontal structures where information, knowledge, and care are reciprocally shared between university/extension and growers/communities. Our outreach activities also include tabling and general public outreach at community events throughout the year.

Project Activities

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Completed Outreach Activities in 2023:

- 13 co-learning events at community garden sites, engaging 73 participant growers and ag educators. These events paired information about mulching and shredded cardboard mulch with relevant seasonal gardening topics. Hands-on activities and take-home instructions were provided.

- 3 neighborhood tours connecting shredded cardboard mulching practices to broader environmental justice and climate change adaptation efforts. 35 participant growers and ag educators attended.

- Engagement at 6 community festivals, facilitating dialogue with 792 participant growers and ag educators about gardening topics, mulch benefits, and climate change adaptation.

- Creation of educational handouts, signs and factsheets on various gardening and mulching topics.

- 3 field day/workshop events at the UMN research plots.

Outreach Activities in Progress:

- Mulch and fertility management materials in multiple formats, informed by the research results and grower experiences.

- Social media, newsletter, and web content to share stories from the project.

- One peer-reviewed scientific publication on the research findings.

- A poster presentation has been accepted for presentation at the 2024 Urban Food Systems Symposium.

- One grower/researcher paired conference presentation per year to share learnings.

- Compilation and sharing of facilitation plans for the co-learning gatherings through grower and extension networks.

- Participatory evaluation at the conclusion of the project.

So in summary, the project has already engaged a large number of growers and ag professionals through a variety of outreach events, demonstrations and educational materials in 2023. Additional outreach through publications, presentations and shareable resources is planned to disseminate the project findings and learnings more broadly throughout 2024.