Progress report for LNC22-471

Project Information

Farmers in the North Central Region are often conflicted about whether to prioritize either soil health and structure or the short-term yield gained by cultivating a smooth planting surface in the spring. This ‘no-till means no-yield’ mentality remains prominent across the region. However, growers are interested in how cover crops can mitigate production challenges like early season excess soil moisture, field trafficability, and labor shortages, especially evidence from trusted neighbors and advisors. To meet the urgent need for practical guidance from trusted sources, the project “Planting Green in the Frozen North” will work with farmers, local government, and commodity groups to develop viable strategies for planting green (e.g., planting annual cash crops into live cover crops). We have established replicated, production-scale research and demonstration sites of soybeans planted into living cereal rye in the heart of the “Frozen North” (northwest and west central Minnesota) to a) provide specific regional agronomic recommendations and b) quantify the effects of planting green on soil properties, disease incidence, and cash crop nutrient supply. Focusing on the production benefits that early spring cover can provide (e.g., weed suppression, retaining soil nutrients, improved trafficability) can convince farmers to enact meaningful system changes. Successful cover crop integration into current cropping systems will have a broad impact, reducing regional erosion and nutrient losses while supporting more resilient farms and communities. This project has the potential to help others to overcome real and perceived cold-weather obstacles to adopting practices that will address the critical need to reduce soil loss within the “Frozen North” and beyond.

Exploring (1) the appropriate timing for terminating a rye cover crop; (2) soil health benefits of continuous living cover; and (3) incidence of soybean disease, weed and pest pressure will support farmers experimenting with planting green and raise awareness among others. We anticipate that 200+ farmers will learn the benefits and challenges of cold-climate cover cropping through on-farm field days. We will highlight our farmer-cooperators so they can become community leaders in peer-to-peer support networks that aim to increase cover crop acres. Findings will also be shared with 5,000+ people through UMN Extension’s platforms (e.g., websites, social media, newsletters, podcasts).

Even as the benefits of incorporating cover crops into agronomic cropping systems are increasingly shown across the North Central region, cover crop adoption remains very limited. Farmers across the region have a longstanding belief that they have no leeway to prioritize soil health over the short-term benefits of planting into a smooth, bare soil surface in the spring. The short window for spring fieldwork across the region is a serious obstacle for farmers interested in incorporating cover crops—specifically, overwintering cover crops—into their cropping systems. Nowhere is cold-climate agriculture more of a challenge than in the US Midwest’s “Frozen North” (Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota). Our project focuses at the heart of the “Frozen North,” the Red River Valley of the North region, which spans northwestern and west-central Minnesota and the eastern Dakotas.

Previous SARE-sponsored research has shown that planting green is a viable strategy for soybeans in Pennsylvania (Project ID: LNE14-331). Additional research has shown that winter cover can provide soil quality benefits, but presents significant management challenges as demonstrated in southern Minnesota (Project ID: LNC17-398). Questions that remain unanswered after these projects include: how much biomass can a winter rye cover crop produce following wheat and following corn? Is it enough to suppress weeds in northwest and west central Minnesota?; What seeding rate is needed to achieve sufficient biomass to positively impact soil health parameters? When is the best time to terminate rye in spring? The answers to these questions are expected to vary across the region, and so our team includes farmerpartners across northwestern and west-central MN, with mean annual precipitation (1981-2010) varying from 22 to 26 inches and mean annual temp (1997-2016) from 37 to 44℉. This project builds on the findings and recommendations of previous projects by focusing on the practical challenge of managing early-spring cover in one of the coldest agricultural regions of the US, the Frozen North.

We hypothesize that incorporating early-spring cover into cold-climate cropping systems will provide significant added value to farmers beyond preventing soil loss. Early-season cover crops protect the soil surface, take up excess nutrients, and reduce soil loss to wind and water erosion. We will also evaluate the ability for early-season cover to mitigate excess soil moisture, improve field trafficability, and reduce pest and disease pressure. If successful, this project will help others to overcome real and perceived cold-weather obstacles and to address critical issues of soil loss within the North Central region and beyond.

The focus of this project is important and timely because the historically severe 2021 drought in Minnesota meant that there were several more spring soil storms than usual due to lack of crop residue and dry soil conditions. Communities suffering in these conditions ask farmers and local governments to please fix this. Farmers ask agronomists and researchers, what can we do without sacrificing yield? Additionally, the near weekly articles in the ag press regarding carbon markets and the associated improvement of soil health measures one can obtain by adopting sustainable cropping practices (no-till and cover cropping) have made more farmers willing to entertain the idea of experimenting with cover cropping. More research in cover cropping under the extreme conditions of the "Frozen North" can de-risk the experiments substantially, protecting farmers who are managing tight margins and high input prices.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Although a short-growing season provides a challenge for farmers, cover cropping and conservation tillage can be successfully integrated into soybean rotations in the Red River Valley of the North.

Objectives & Approach

This project addresses multiple agronomic impacts of planting green (i.e., planting soybeans into a living rye cover crop). This project will meet this goal by achieving the following objectives:

- Determine optimal combinations of seeding rate and termination timing for planting green in a wheat-soybean, corn silage-soybean, or corn grain-soybean rotation.

Cereal rye is a hardy, overwintering cover crop capable of surviving the harsh winters of the Northern Great Plains. The tradeoff for its winter-survivability is that it requires additional attention in the spring to avoid interference with the subsequent cash crop. Because we will be planting green, we cannot use tillage to terminate the rye cover. Instead, we will rely on glyphosate for rye termination. Finding both the optimal seeding rate and the optimal termination timing will be critical to control the rye cover and avoid associated soybean establishment issues in the spring. - Quantify the effect of cereal rye on agronomic production impacts such as: a) soybean nutrition, b) soil microbial activity, and c) incidence of soybean disease and weed pressure.

Cereal rye is often promoted for its ability to scavenge nutrients from the prior year’s cash crop. Just prior to cover crop termination, we will sample above-ground cereal rye biomass to assess nutrient content. To determine the timing of nutrient release by the rye cover crop, we will collect soil samples from the top 8 inches of each plot twice during the growing season (4 weeks and 12 weeks following cover crop termination). Target nutrients that we will monitor will include nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sulfur, and chloride.

Soil microbial activity is a key factor in residue decomposition, nitrogen availability, and carbon sequestration potential. These effects will be monitored by measuring potentially mineralizable carbon (as described in Franzluebers et al. 2000) and organic nitrogen pools (as described in Hurisso et al. 2018) in soil samples taken from each plot at 4- and 12-weeks following cover crop termination. Soil moisture and temperature in each plot will be monitored on a weekly basis. Soil aggregation, a common soil health metric, will be monitored in each plot at the beginning and end of the experiment.

Each year, an estimated 1.48 acres in western Minnesota are at risk of producing soybeans that suffer from iron deficiency chlorosis (Hansen et al. 2004), a disease common to NW and WC MN that can reduce yield by more than 32%. Excess nitrates in the soil profile can worsen IDC symptom severity (Wiersma, 2010). We will monitor incidence and severity of IDC in the different plots, to cross reference with plant-available nitrogen measurements. The effects of cover crop treatment on weed species composition and biomass will also be assessed. Specifically, weed species composition, percent control and total above-ground weed biomass from three areas of each plot will be determined 28 days after cover crop termination (Yenish et al. 1996).

- Develop educational and outreach material on the nutrient scavenging potential of cereal rye in Minnesota

This work will provide valuable insight into what agronomic impacts farmers can expect to see when integrating cover crops into their rotations. Our project team and our farmer collaborators will work together to share the benefits and challenges of cold-climate cover cropping through on-farm field days. These on-farm meetings will highlight our farmer-collaborators and will serve as kick-off points for the initiation of peer-to-peer support networks with the aim of increasing cover crop acres. Findings will also be shared with 5000+ people through UMN Extension’s platforms (e.g., websites, social media, newsletters, radio interviews, press releases, a fact sheet and podcast), and through all team members’ (including our farmer-collaborators’) broad social networks.

Experimental Design

In Summer 2021, we established a large-scale, coordinated experiment across seven on-farm research sites and two Research & Outreach Centers to design viable continuous-living-cover systems for the North Central region. Funding for the first year of this project was provided by MN Soybean Research & Promotion Council. NCR SARE funding allows us to continue this experiment for a combined total of four soybean cropping years planted green in both Northwest Minnesota and West Central Minnesota (Figure 1).

This project uses a two-pronged approach to evaluate both practice efficiency and practicality. Plot-scale research will allow us to determine the most effective approaches. On-farm research will test the viability and practicality of these options. Post-cover crop yield and nutrient use efficiency of these systems will be quantified and demonstrate the benefits and challenges of introducing cover crops into the cold-climate cropping systems of the North Central region.

On-Farm Locations

We established strip plots at seven on-farm locations in 2022, six locations in 2023, and X locations in 2024. In fall 2024, we established three on-farm locations with our farmer collaborators for the final growing season of this project (2025). We have evaluated the following four treatments at on-farm sites:

- No cover crop control

- Rye terminated 7-14 days prior to planting

- Rye terminated within 24 hours of planting

- Rye terminated 7-14 days after planting

Each treatment was replicated three times, for a total of twelve harvested strips. Strips varied, but were wide enough to allow for one combine pass in soybeans that excludes sprayer track damage.

Small Plot Locations (Crookston and Morris)

We established plots for the 2022 and 2023 growing season at the Northwest Research & Outreach Center in Crookston, MN and the West Central Research & Outreach Center in Morris, MN. Following the discontinuation of small plot research at the West Central Research & Outreach Center in 2023, we established plots at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service Soil Management Research Unit in Morris, MN in Fall 2023 and Fall 2024.

The two small plot locations focused on optimizing management of cereal rye for local rotations (wheat-soybean in Northwest Minnesota; corn-soybean in West Central Minnesota). These plot-scale experiments will assess two seeding rates of cereal rye, two tillage systems, and three termination timings with four replicates:

Tillage treatments:

- Fall chisel plow and field cultivation

- No-till

Cover crop seeding rate treatments:

- No cover crop

- 20 lb/A Cereal Rye

- 40 lb/A Cereal Rye

Cover crop termination timings:

- 1-2 weeks before planting

- At planting

- 1-2 weeks after planting

All Sites

Both spring rye survival and soybean establishment following rye termination were evaluated. We monitored soil nitrogen availability before, during, and at the end of the growing season in each plot. Soil health tests assessed biologically relevant nutrient pools such as potentially mineralizable carbon, water-extractable carbon and nitrogen, and aggregate stability.

Soybean disease, pest pressure, and weed management were also evaluated. Symptoms of iron deficiency chlorosis were visually assessed from three areas of each plot using a visual rating scale. Walking a transect through each plot, plants were visually inspected for disease incidence and severity and insect injury in the lower, middle and upper canopy. The effects of cover crop treatment on weed species composition and biomass was assessed. Specifically, weed species and total above-ground weed biomass from three areas of each plot were determined about 28 days after cover crop termination.

This project has a high potential for impact. All team members are committed to engaging with farmers on how best to achieve continuous living cover cropping systems. Project findings will be shared with farmers at winter extension meetings, at summer field days, and through fact sheets, news articles, social media, and radio, and with the scientific community through society meetings and peer-reviewed publications.

References

Franzluebbers, A.J., R.L. Haney, C.W. Honeycutt, H.H. Schomberg, and F.M. Hons. 2000. Flush of Carbon Dioxide Following Rewetting of Dried Soil Relates to Active Organic Pools. Soil Science Society of America J. 64: 613-623.

Hansen, N.C., V.D Jolley, S.L. Naeve, and R.J. Goos. 2004. Iron Deficiency of Soybean in the North Central US and Associated Soil Properties. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 50(7): 983-987.

Hurisso, T.T., D.J. Moebius-Clune, S.W. Culman, B.N. Moebius-Clune, J.E. Thies and H.M. van Es. 2018. Soil Protein as a Rapid Soil Health Indicator of Potentially Available Organic Nitrogen. Agric. & Environ. Letters, 3: 180006.

Wiersma, J.V. 2010. Nitrate-induced iron deficiency in soybean varieties with varying iron-stress responses. Agronomy J. 102(6): 1738-1744.

Yenish, J.P., A.D. Worsham, and A.C. York. 1996. Cover crops for herbicide replacement in no-tillage corn (Zea mays). Weed Technol. 10: 815-821.

On-farm results

2023

Waiting to terminate a rye cover crop until two weeks after planting increased the risk of yield loss. At three of the six locations (two in northwest and one in west-central MN), soybean yields were significantly lower if rye was terminated at the latest timing. The two northwest locations also had significantly lower yield when rye was terminated at soybean planting.

Surprisingly, the Granite Falls location that received between 6 and 8 inches less rain throughout the growing season compared to normal did not see lower yields with rye termination delays. The Tintah location, which received 2 to 4 inches less rain than normal, did see a reduction in soybean yield at later timings. Oddly, the sites with the worst yield hit due to late CC termination were not always the sites with the largest amount of rye biomass, suggesting that rye water uptake alone cannot explain the effect. Precipitation in 2023 was highly variable, and timely rains at some sites were likely the key to stable yields irrespective of CC treatment.

Terminating rye two weeks before soybean planting only lowered soybean yields in one of the six sites, so this practice appears less risky. This is similar to 2022 soybean yields, where only two of the five sites found soybean yield losses if CCs were terminated before planting.

2024

At the time of this report, we have not yet analyzed on-farm results for the 2024 growing season.

Small plot trial results

2023

Northwest Minnesota we evaluated soybeans following spring wheat. At these plots, we saw no differences in soybean yield based on tillage treatment, cover crop seeding rate, or termination timing.

In West Central Minnesota we evaluated soybeans following corn grain or corn silage. For soybeans following corn grain, we did not see any differences in soybean yield based on tillage treatment or termination timing. We did see a significant change in yield due to seeding rate at these plots. The no-rye treatment yielded higher than the 20 and 40 lb/ac rye seeding rate treatments. For soybeans following corn silage, we saw a significant interaction between termination timing and seeding rate on soybean yield. Here, there was no difference in yield based on seeding rate within 1st or 2nd termination timing window. Two weeks after planting, soybean yields were greater for the 0 lb/ac seeding rate than the 40 lb/ac seeding rate. At the 20 lb/ac seeding rate, pre-plant cover crop termination resulted in greater soybean yields than post-plant termination. At the 40 lb/ac seeding rate, both pre-plant and at-plant cover crop termination resulted in greater soybean yields than post-plant termination.

2024

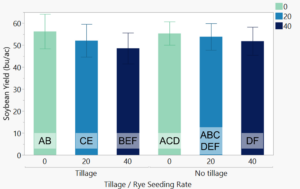

Northwest Minnesota we evaluated soybeans following spring wheat. At these plots, rye seeding rate significantly affected soybean yield. Soybean yield was greatest for the 0 lb/ac treatment at 56 bu/ac. We observed a significant 3 bu/ac yield decrease for rye seeded at 20 lb/ac (yield = 53 bu/ac), and another significant 3 bu/ac decrease for rye seeded at 40 lb/ac (yield = 50 bu/ac). We also observed a significant interaction between tillage and rye seeding rate. Specifically, we observed that rye seeding rate exhibited a stronger negative effect on soybean yield in conventionally tilled plots than in no-till plots (Figure 2).

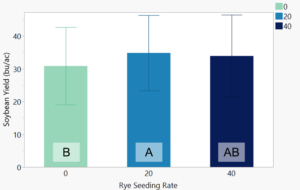

In West Central Minnesota we evaluated soybeans following corn grain. For soybeans following corn grain, we did not see any differences in soybean yield based on tillage treatment or termination timing. We did see a significant change in yield due to seeding rate at these plots, and it was different from the effect we saw in West Central Minnesota in 2023 or in Northwest Minnesota in 2024. Here, the 20 lb/ac treatment yielded about 4 bu/ac higher than the 0 lb/ac rye seeding rate treatment (Figure 3).

2025

At the time of this report, our small plot field trials at the USDA-ARS location in Morris are at risk. Dr. Bernards, a technical advisor who joined our project as a weed specialist in 2023, had his position terminated by Executive Order on Friday, February 14, 2025. He was still in his probationary period. Based on our experience working with Dr. Bernards on this project, his early termination was unwarranted. Through retirements and the deferred resignation program, the Morris lab has lost all of their farm/operation staff. Those left do not have the farm-equipment operating experience needed to plant and harvest our previously established plots. It is looking like we will need to abandon these small plots for the 2025 growing season. Loss of our research site in Morris means that we will not have a location for soybeans following corn in 2025. This will significantly affect our ability to complete the project as planned, and we are still weighing our options for proceeding in the final year of the trial.

Education

Our educational approach is multi-faceted to maximize interest and engagement. First, we to reach out to a broad audience through presentations at large events/conferences and to summarize our findings in writing as part of large efforts such as the University of Minnesota Extension's Minnesota Crop News weekly blog. For those individuals who are interested in learning more about the project, we offer workshops and field days where we can engage one-on-one, answer questions, and allow the farmer participants to share their experiences to encourage peer-to-peer learning.

Project Activities

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Consultations

Dr. Pease provided an in-person consultation to a Northwest Minnesota farmer who is switching to the practices covered by this project (conservation tillage and cover cropping)

On-Farm Demonstrations

A key component of this project was demonstrating practice performance on-farm. In 2023 we had 6 farmers participate in our project and host on-farm demonstrations. One of these farmers also hosted a field day event (described below).

Field Days/Workshops

We conducted three field days that featured this project. Both were held in West Central Minnesota. One was located at one of our on-farm trial sites. The other two were held at the University of Minnesota West Central Research & Outreach Center in Morris, MN.

"Protect Your Field's Investment"

16 Aug 2024, Granite Falls, MN

Attendees: 20 farmers, 16 agricultural professionals

“Soil Solutions Field Day”

7 Sep 2024, Morris, MN

Attendees: 46 farmers, 20 agricultural professionals

“Thriving Roots: Women in Ag Field Day”

8 Sep 2024, Morris, MN

Attendees: 9 farmers, 16 agricultural professionals

Presentations

“Current Research Support for 4R Practices in Northwest Minnesota”

Soil Health Field Day, 15 Aug 2023, Breckenridge, MN

Attendees: 10 farmers and 10 agricultural professionals

“Planting soybeans into a growing rye cover crop”

On-Farm Research Network Symposium, 13 Dec 2023, Grand Forks, ND

Attendees: 50 farmers and 20 agricultural professionals

“Planting Green Along the Red”

Prairie Grains Conference, 14 Dec 2023, Grand Forks, ND

Attendees: 40 farmers and 10 agricultural professionals

"Planting Green"

Midwest Cover Crops Council, Indianapolis, IN, 13 Feb 2024

Attendees: 20 farmers and 40 agricultural professionals

"Let's talk thirsty cover crops"

Strategic Farming: Let's Talk Crops Webinar Series, Online, 28 Feb 2024

Attendees: 100 farmers and 80 agricultural professionals

Learning Outcomes

- cover crop management

Project Outcomes

Changing management of cover crops to improve crop yield outcomes