Final report for LNE14-331

Project Information

No-till farmers in the mid-Atlantic want more from their cover crops (CC). Some “plant green” (PG), meaning delay CC termination until main crop planting to get an additional week or more of biomass accumulation and ecosystem services. The impacts of this practice on mid-Atlantic grain production are not well quantified, so we examined PG at four sites with corn and five sites with soybean for three years in Pennsylvania. Sites included two Penn State research farms and three cooperating farms. Treatments were preplant-killed CC (PK) vs. PG. Variables of interest included cover crop biomass; soil moisture and temperature at cash crop planting and throughout the growing season; cash crop population; slug feeding damage on cash crops; and cash crop yield and yield stability across site-years.

From the 12 and 14 site-years of this study for corn and soybeans, respectively, we found that planting green: i) significantly increased CC biomass, resulting in cooler and drier soils at corn and soybean planting and wetter soil later in the growing season; ii) reduced or did not affect slug feeding in soybeans, while increasing or decreasing slug feeding in corn; and iii) did not influence soybean yield, but was more likely to reduce corn yield. This study has illuminated the impacts of soil cooling under PG, and the vulnerability of corn to these effects, especially in high-yielding environments; and the excellent adaptability of soybean to this practice across locations, variable weather conditions, and agronomic management. Planting green can increase CC biomass and associated soil conservation and ecosystem services, but also requires more attention to cover crop management for successful crop production.

Research findings were presented at over 20 outreach events, including field days, workshops, and academic meetings. Over 900 farmers and 600 agricultural service providers attended outreach events, with approximately 50 farmers adopting PG, and more adopting the practice each year as knowledge of the system multiplies. An extension bulletin summarizing the results of the project has been published online and is downloadable by the public.

As a result of these activities, on over 10,000 acres, 50 farmers who use no-till and cover crops will delay cover-crop termination in spring until or close to crop planting, thereby enhancing soil conservation and health, reducing crop losses to slugs and weeds, and improving cash crop establishment and yields.

The benefits of no-till have been well established, including reduced fuel consumption, reduced soil erosion, improved soil physical properties and soil quality, and improved water quality. We also know that some benefits of no-till are enhanced by planting cover crops, which provide additional benefits associated with living cover and roots such as weed suppression; beneficial arthropod habitat; increased soil organic matter, biological activity and structure; and nitrogen provision (legumes) or sequestration (non-legumes). However, incorporating no-till + cover crops can be challenging, especially in the mid-Atlantic. Both practices cool soil (this effect is even stronger when no-till and cover crops are used together), shortening the growing season for summer annual crops, as farmers wait longer in the spring for soil to warm up and dry out. Problems with stand establishment can then result from cooler, wetter soils, and interference from cover crop residue. Slugs, molluscan pests that eat crop seeds and defoliate young plants, are another common challenge associated with no-till and cover crops. Because they prefer moist and cool habitats, they thrive in systems without tillage that can bury eggs and warm-up and dry out soil.

A survey of the Pennsylvania No-Till Alliance in 2013 revealed that some PA farmers “plant green” to extend the soil conservation and soil health benefits of cover crops while mitigating the challenges of wet soil and slug damage associated with pairing cover crops with no-till. Planting green refers to planting cash crops into living cover crops instead of the more common practice of planting into desiccated cover crops killed with an herbicide a week or more beforehand.

Planting green has not been extensively studied nor these claims quantified, so at Penn State University we conducted a three-year study at five different locations in central and southeastern Pennsylvania to evaluate the effects on corn and soybean performance of “planting green” compared to early cover crop termination (early kill).

Cooperators

- (Educator)

Research

Terminating cover crops at or close to planting the cash crop (i.e., “planting green”) would: i) reduce soil moisture and improve soil conditions for seed placement; and ii) reduce slug herbivory and weed establishment; thereby enhancing crop establishment and yields.

Rye seeding rate, N rate, and rye termination timing effect on soybean production:

The first part of the study focused on rye seeding rate, topdress nitrogen rate, rye termination timing, and their influences on soybean production. Since this experiment was complicated and required fine control of management, it was completed at 2 Penn State research stations over 3 years.

The experiment was initiated in September 2014 at the Southeast Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Landisville, PA (heretofore referred to as Landisville), and at the Russell E. Larson Agricultural Research Center in Pennsylvania Furnace, PA (heretofore referred to as Rock Springs). The design was a randomized split-split plot with four blocks (replications). Rye seeding rate was the main plot (60 x 120 ft), with three levels: 1x (30 lb/A), 2x (60 lb/A) or 4x (120 lb/A); termination timing was the split-plot (60 x 30 ft), with two levels: preplant-killed (PK) or planted green (PG); and nitrogen topdress rate was the split-split plot (60 x 15 ft), with two levels: 1x (30 lb/A) or 2x (60 lb/A).

Nitrogen topdress applications were applied at green-up in mid-March to early April.

Cover crop species and termination timing effect on corn production:

The second part of the study focused on crimson clover and a crimson clover + rye mixture in addition to rye termination timing effects on corn production. Again, due to the complicated nature of this experiment, it was completed at 2 Penn State research stations over 3 years.

The experiment was initiated in September 2014 at Landisville and Rock Springs. Factors were cover crop (crimson clover, rye, or crimson clover/rye mix) and termination timing (PK or PG). Factors were fully crossed in a randomized complete block design with four blocks (replications). Plots were 60 ft wide (24 corn rows) and 60-75 ft long, depending on available field space. Rye was seeded at 120 lb/A in 2014, and 90 lb/A in 2015 and 2016; crimson clover seeded at 25 lb/A, and rye/crimson clover mix seeded at 60/20 lb/A in 2014 and 90/12 lb/A in 2015 and 2016.

5-Site Cover crop termination timing effect on corn and soybean production:

In the third part of the study, we expanded the scope of the experiment to 5 sites, including 3 farmer cooperator locations, and examined the influence of planting green on both corn and soybean production under a range of crop rotations, equipment, planting and termination dates, and environmental conditions.

The experiments were initiated in fall 2014 and conducted for three growing seasons at five locations each season: two Penn State University Research Stations and three cooperating grower sites in central and southeastern Pennsylvania. A rye or triticale cover crop was seeded anywhere between 30-120 lb/A. Cover crop termination timing was the treatment within each cash crop at each site; the two treatment levels were: preplant-kill (PK) or terminated after planting green (PG). The experiments were set up in a randomized complete block design with 4 blocks (replications).

All 3 experiments:

Approximately 2 weeks before the desired main crop planting date each year, early-killed treatments were sprayed with glyphosate (or the cooperator’s choice of burn-down herbicide). Once when the PG treatment reached the desired biomass accumulation, or when field conditions permitted, cash crops were planted into PK and PG treatments on the same day. Seed insecticide and fungicide were not used at any location to prevent non-target injury to slug predators. The PG treatment was terminated with a herbicide within 5 days after planting.

At all sites, cover crop above-ground dry matter was determined at both PK and at PG by clipping tissue to the soil surface, drying to stable weight, and weighing. Soybean damage assessments were performed at the cotyledon (VC) stage, and corn damage assessments were performed at the five-leaf (V5). Total soybean plants in 5 ft row length, and corn plants in 10 ft were counted in five random locations in each plot, avoiding border rows; the number of plants with signs of slug damage was also recorded at each location. Main crop populations and percent of plants with slug damage were extrapolated to per-acre values and averaged. A hand-held soil moisture meter was used to measure volumetric water content (VWC) to a 3 in depth and between main crop rows at or as soon as possible after main crop planting; measurements were also taken weekly thereafter. Soil temperature was measured at the same time as soil moisture using a digital thermometer. The hole made using the FieldScout was used as the pilot hole for the thermometer, so that readings were taken from the same 0-8 cm depth and location.

Grain was harvested and yield determined, from the center 2 rows of each plot at research station and center 6 rows of each plot at cooperator sites with at least 2 rows of border left between plots.

Within each experiment, treatment effects on cover crop dry matter, cash crop populations, slug damage, soil moisture and temperature, and cash crop yield were compared across sites and years.

Rye seeding rate, N rate, and rye termination timing effect on soybean production:

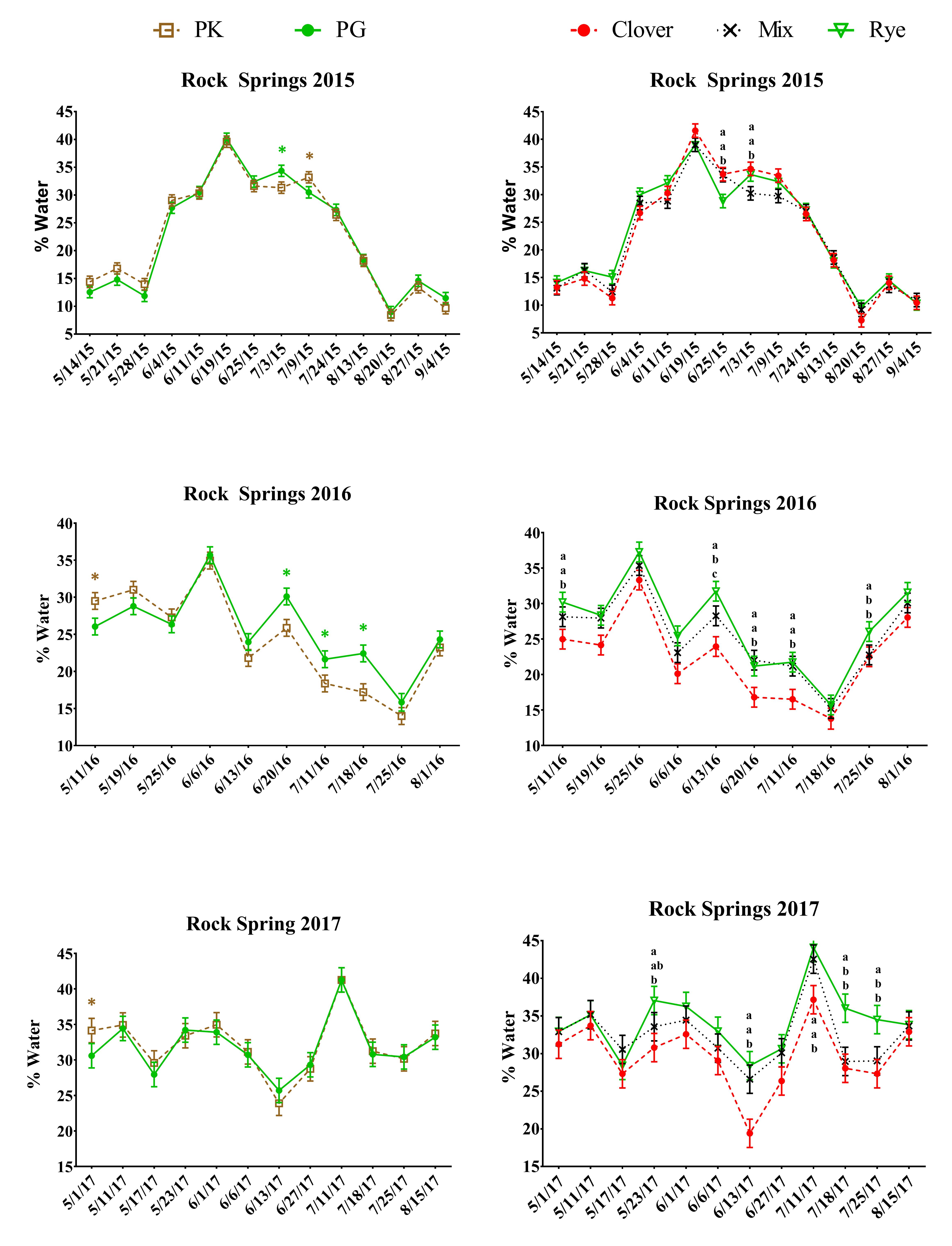

At Landisville and Rock Springs, PG increased rye biomass by 48-169%. PG soil (0-3 in) was generally drier at planting, wetter later, and cooler for much of the growing season compared to PK. Slug activity-density was higher in wet 2016-2017 than 2015, and PG reduced slug damage compared to PK in three of four site-years measured. PG soybeans yielded similarly to the PK most consistently when the 60 lb/A seeding rate was combined with the 30 lb/A N rate. At the higher seeding and nitrogen rates we found that rye lodging and residue interference complicated stand establishment and reduced soybean populations. Our results corroborate grower anecdotes that PG can help manipulate soil moisture and reduce slug activity. However, for subsequent soybean success, we recommend rye seeding rates of 60 lb/A or lower, conservative N rates, and killing rye early if dry conditions are predicted to persist.

Cover crop species and termination timing effect on corn production:

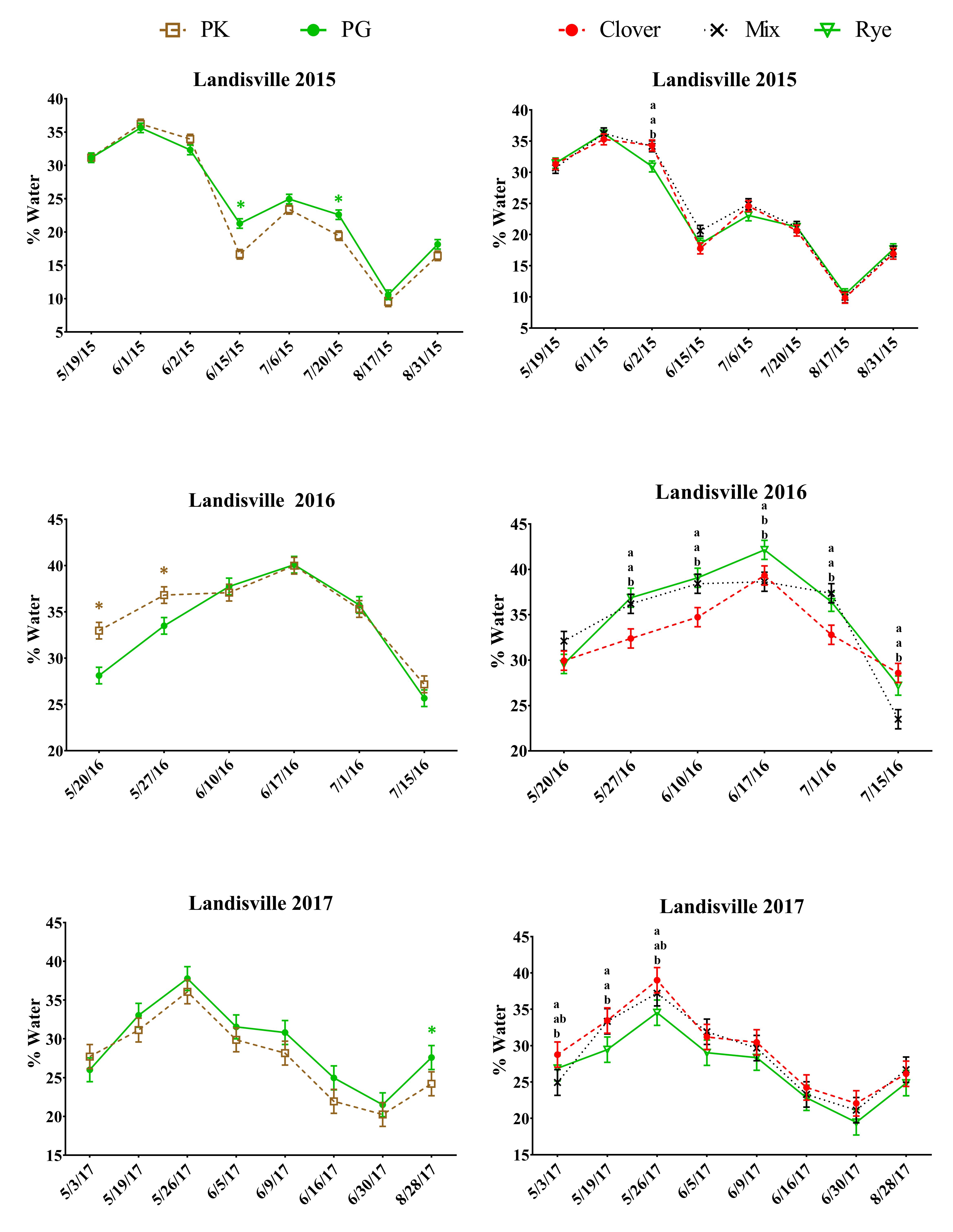

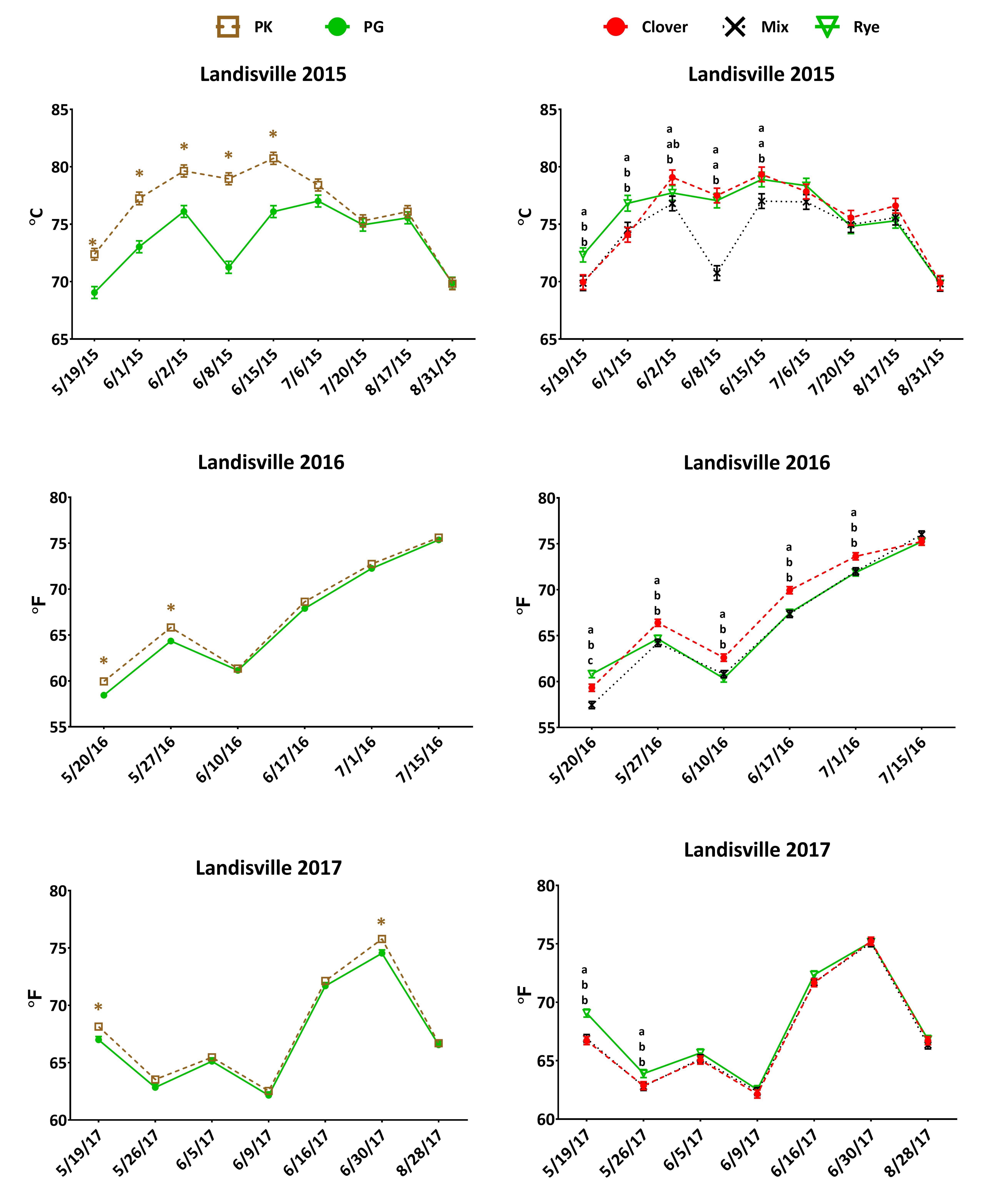

Biomass of CC increased 30-173% across CC with 6-16 days between PK and PG. PG dried soil initially, conserved soil moisture later in the growing season and cooled soil all growing season; crimson clover also caused dryer and warmer soils compared to rye or the mix (Fig. 1-3). Slug damage was not significantly influenced by PG or CC. At Rock Springs, corn yield was 10% lower in PG compared to PK across CC in dry 2015, and 12% lower in PG crimson clover compared to early across years; the rye + crimson clover mix yielded intermediate to the pure constituents. The best predictors of corn yield across cover crops were soil moisture and temperature at corn planting, and corn population. Though corn population and yield were not different between early-kill and PG rye, soil was significantly cooler, and often significantly drier at planting in PG compared to early-kill; therefore, potential for reduced N mineralization associated with high C: N and cooler, drier soil with PG rye remains a concern. PG can help manage soil water, but we caution against PG and crimson clover in dry springs due to excessive drying, and recommend attention to nitrogen management when PG into rye.

5-Site Experiment:

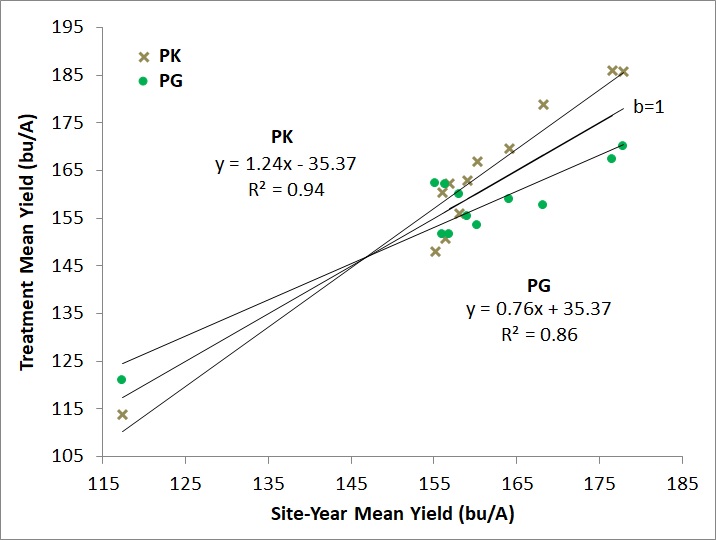

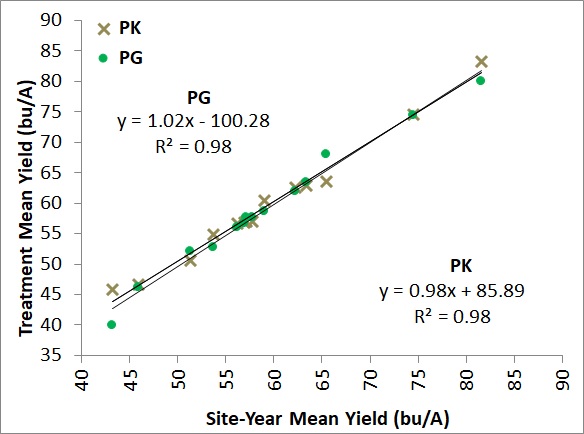

Planting green increased CC biomass 94% to 181% compared to PK, substantially increasing the amount of ground cover. Except for two site-years, soil was 8% to 24% drier, and 1.3 to 4.3°F cooler at planting in PG compared to PK. Cash crop population was not influenced by termination timing. Slug damage was not different, lower, or higher in PG corn, and not different or lower in PG soybeans compared to early-kill. Corn yield was reduced by PG in higher yielding environments, but on average PG corn yield in lower yielding environments was no different (Fig. 4); conversely, soybean yield was stable across locations, and not affected by treatments (Fig. 5).

This 5-site experiment revealed that across diverse Pennsylvania sites and weather, equipment, and agronomic management, soybeans maintained similar yield regardless of cover crop termination timing, whereas corn yield was more likely to be reduced by PG, especially in high-yielding environments. Corn population is a main predictor for corn yield, and corn relies on plant available N in the soil for growth, making it vulnerable to reductions in crop population due to residue interference, slug feeding on seeds or over-dried soils, as well as slowed N cycling in cool soils. However, the indeterminate growth and biological N fixation of soybeans allowed for compensation if populations were reduced (populations were not significantly different across the 14 site-years) likely negated yield impact from cooler soils. We found that PG can increase CC biomass and potential ecosystem services, but also requires more grower knowledge and attention to cover crop management for successful crop production. We suggest that interested growers start learning how to plant green with soybeans, and emphasize the greater risks of PG with corn.

These three experiments provide a valuable addition to previous research on no-till cover crop management, and insight on the numerous remaining knowledge gaps of planting green (PG). Many results were similar across all 3 experiments. We found that weather played a pivotal role in the performance of PG, with significant soil drying providing potential for improved stand establishment in wet springs, but negative consequence in dry springs. Soil moisture conservation later in the year by more massive PG residue could also provide benefits in dry summers, but this benefit is limited in years with ample summer rainfall. Soil drying, cooling, and residue interference of increased cover crop biomass when PG posed challenges, especially for corn and also in the dry 2015 spring, and very wet and cold 2017 spring.

Though this study helped quantify many of the agronomic and agroecological effects of PG, it is one of very few studies focused on the practice, and there is obviously still much to learn. For instance, evaluation of PG into other cover crops besides rye and crimson clover is warranted; specifically, Pennsylvania farmers have shown some interest in wheat as an alternative to rye, due to lower cost of wheat seed and slower spring growth than rye. Additionally, to reduce risk of yield loss with corn, there is work to be done regarding optimum CC biomass, equipment attachments and settings, N rate and application timing, and hybrid selection. Furthermore, the role of fall CC planting date on slug and slug predator populations, and long-term influences of PG on arthropod communities, slugs, and other pests should be evaluated. Grower decisions whether or not to plant green would be aided by an in-depth economic analysis including: i) potential pesticide reduction due to weed and/or slug suppression with PG; ii) cash crop seed cost reduction if seed treatment is eliminated; iii) reduction in CC seed cost if seeding rate is reduced; iv) cost for alterations to or purchase of equipment; v) any changes in fuel use; and vi) changes in time spent managing PG fields. A decision-making tool to help growers manage CC biomass could also ease the transition to PG. Lastly, soil health impacts beyond biomass/residue cover were beyond the scope of this study, but are of great interest to farmers. We can infer benefits based on previous literature, but changes in soil health have not been measured in this system.

The challenges of PG are recognized by growers who use the practice, yet interest in PG has continued to grow. The 2016-2017 SARE national cover crop survey questioned farmers who had planted green how the practice affected cash crop management. In the annual report of that survey, 260 respondents found management was more difficult when PG, while 143 found management simpler. However, of those who found planting green made management more difficult, 38% thought the benefits outweighed the challenges, 44% were still evaluating whether the benefits outweighed the challenges, and only 18% planned on moving away from planting green in the future. Further, despite some negative ramifications of PG with corn especially, growers we consulted whom are passionate about soil health accept an occasional yield loss with satisfaction of doing what they believe is the best possible practice for long-term environmental and economic sustainability of their soil and farms.

This study provides a robust dataset suggesting several management practices to mitigate these challenges and increase grower success with PG: i) reduce fall CC seeding rates; ii) do not over-fertilize the CC; iii) use crimson clover cautiously; iv) use appropriate, well-maintained equipment adjusted to specific field conditions, including using a planter instead of drill for soybeans; v) kill CC early if dry conditions are predicted to persist around planting; and vi) attempt PG with soybeans before trying with corn.

Education

Educational activities included field days at the Penn State research sites, our cooperators' commercial farms, two additional farmers whom have adopted planting green, and a field day hosted by Cumberland Planter Company, a Pennsylvania agricultural equipment company. We also presented our research results during winter extension meetings and scientific conferences to diverse audiences of farmers, agricultural educators and consultants, agency personnel, and researchers. Most of the educational presentations were presented by Dr. Heidi Myer Reed whom conducted this research and has completed her doctoral research and graduated from Penn State. Other members of our research team also often co-presented about aspects of this work, or presented project results at other meetings. Dr. Heidi Reed is currently preparing and submitting three scientific manuscripts from this research and prepared the Planting Green Summary Bulletin (ART-5719) with input from the project team. Dr. Reed is currently a Cooperative Extension Educator in York County, Pennsylvania.

Milestones

Farmers in Pennsylvania learn about the benefits of terminating cover crops and “planting green” through presentations and educational handouts at our two research farm field days, and at Penn State pest management field days, the Diagnostic Clinic, and winter extension meetings.

800

300

140

March 31, 2016

Completed

March 31, 2016

In summer 2015 (first summer of field research), preliminary results were presented and discussed with growers, extension personnel, and agricultural industry professionals from several northeastern states and Canada at five outreach events. Events included: Penn State Crop Management Extension Group Field Day, attended by 50 extension personnel; Southeast Agricultural Research and Extension Center Farming for Success Field Day (June 25), 200 attendees; Penn State Crop Diagnostic Clinic (July 28-29), attended by 110 farmers and ag industry professionals; Schrack Farms Field Day (September 1), attended by 50 farmers; and Cover Crops Field Day at Myers Farm (September 23), attended by 30 farmers and consultants.

In winter 2016, results were presented and discussed with growers, extension personnel, agricultural industry professionals, and agricultural educators from Pennsylvania. Events included: Pennsylvania Agronomic Education Conference (January 22), attended by 110 agricultural educators; Potter County Crops Day (January 29), attended by 85 growers and extension personnel; Conewago and Chiques Watersheds Winter Farmers Meeting (February 25), attended by 60 farmers and technical service providers

Farmers contact members of our project team to gather more information and adopt planting green. They share their experience with members of our project team and other farmers through PSU and No-Till Alliance field days and meetings in summer 2016 and winter 2017.

8

March 31, 2016

Completed

March 31, 2017

We were asked to present our research results to the field and forage crop cooperative extension educators and multiple farmer organizations in 2016 and 2017. Some farmers contacted their local county cooperative extension educators. In each of these presentations we reported what we had learned and asked participants to share their experiences, strategies and questions regarding planting green. In addition, when we organized a field day in summer 2017 at one of the cooperating commercial farms we included and facilitated a farmer panel discussion of planting green. Examples of these events include the Pennsylvania Agronomic Education Conference (January 22, 2016), attended by 110 agricultural educators and Improving Soil Health with Cover Crops and Planting Green Field Day (June 22, 2017), attended by 81 farmers, agency, industry, extension, and non-profit personnel.

Farmers learn about the benefits of planting green at project field days at the three cooperating farm and two research farms, at the NESARE Sustainable Dairy Cropping System field day; as well as winter meetings, state-wide conferences, regional and county crops days, and summer educational events described in milestone one, and Penn State’s Ag Progress Days.

600

100

181

March 31, 2017

Completed

March 31, 2017

In summer 2016, results were presented and discussed with growers, extension personnel, agricultural industry professionals, agricultural educators, and legislators from Pennsylvania. Events included: Penn State Crop Diagnostic Clinic (July 21-22), attended by 115 farmers and ag industry professionals; Penn State Ag Progress Days Manure Hauler Training (August 18), attended by 46 commercial manure haulers; and Penn State Ag Council Research Tour (September 22), attended by 120 legislators and extension personnel.

Additional farmers adopt planting green, consult with project members and obtain technical assistance. Farmers share their experiences at field days and meetings in summer 2017 and winter 2018.

27

24

March 31, 2018

Completed

March 31, 2018

We estimate this number by suggesting that 5% of farmers participating in our field days within the time frame of this milestone (March 31, 2016-March 31, 2018) attempted planting green. The number in reality may be far higher, as the approximately 300 agricultural service providers who participated in our events likely multiplied this outreach effect.

Farmers learn about the benefits of planting green through field days, newsletters and farming news articles, fact sheets and the educational events described in milestone 3.

300

380

249

March 31, 2018

Completed

March 31, 2018

In 2017, results were presented and discussed with growers, extension personnel, agency and agricultural industry professionals from Pennsylvania at six outreach events. Events included Improving Soil Health with Cover Crops and Planting Green Field Day (June 22), attended by 81 farmers, agency, industry, extension, and non-profit personnel;

Penn State Crop Management Extension Group Field Day (June 27), attended by 23 extension personnel; Farming For Success Field Day (June 29), attended by 230 farmers, agency, industry, and extension personnel; Pennsylvania No-Till Alliance Summer Field Day (July 27), attended by 240 farmers, agency, industry, extension, and non-profit personnel; Kanagy Field Day (August 10), attended by 40 farmers, agency, and industry personnel; and Soil and Water Conservation Society Keystone Chapter Annual Meeting (August 16), attended by 15 agency personnel.

Farmers describe the multiple benefits of planting green in our follow-up

survey.

35

50

12

March 31, 2019

Completed

March 20, 2019

An eight-question survey was distributed on paper to all attendees of three, “Connecting Soils and Profits” events in Centre, Bradford, and Montour counties in Pennsylvania. These counties are in central and northeastern Pennsylvania. We also solicited responses from readers of Penn State Extension’s Field and Forage Crops Team weekly electronic newsletter, “Field Crop News” using Qualtrics Survey Software. The same eight questions were asked, and responses were recorded electronically. Readership of Field Crop News extends throughout the mid-Atlantic. All survey responses were compiled; if respondents did not follow question directions (i.e. check marks instead of rank-order), the response for that question was eliminated.

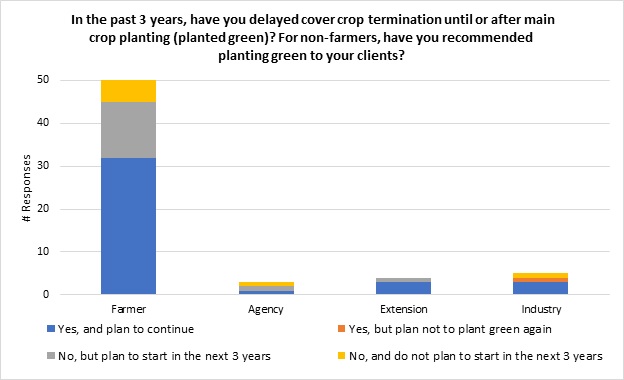

First, participants were asked to self-identify as either “farmer,” “government agency personnel,” “Extension,” or “ag industry.” Our solicitation returned 62 responses (15 online) comprised of 50 farmers (8 online), 3 government agency personnel (NRCS, conservation district, etc.), 4 extension personnel (all online), and 5 ag industry personnel (3 online).

Participants were then asked several questions about their prior experience with planting green, plans for planting green and cover crop management, and whether Penn State Extension research has informed their cover crop management decision making in the past three years or plans for the next three years. Results are presented below.

Of the 62 respondents, 63% said they have planted green in the past 3 years and plan to continue, while 24% have not yet planted green, but plan to start in the next 3 years. Eleven percent of respondents have not planted green and do not plan to start in the next 3 years. Only 2% (one individual) has planted green in the past 3 years but does not plan to continue.

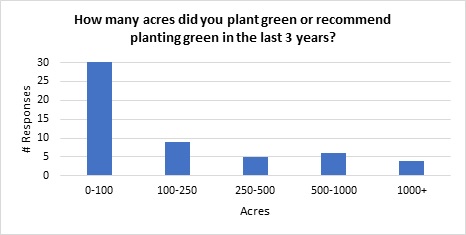

Most respondents appear to be using or trying this practice on small acreages—48% have planted green or recommended planting green on 0-100 acres in the past 3 years. About one third (32%) have done so on 100 to 1000 acres. Only 6% (4 respondents) have planted green or recommended planting green on greater than 1000 acres in the past 3 years. This could be because Pennsylvania farms are relatively small on average (130 acres, USDA NASS 2012 Census of Agriculture), or because respondents who were new at planting green were cautions with the amount of acreage on which they tried the practice.

The two most important reasons our respondents planted green in the past 3 years were soil health and conservation and to maximize cover crop benefits, which ranked in the top 5 reasons for 96% and 89% of respondents, respectively. Weed suppression was the next most frequent and highest rated reason respondents planted green, with 82% listing it in the top 5, followed by growing more biomass (71%) and soil moisture management (69%). Other options to choose from that were less important to respondents were: other (20%), increased main crop yield (20%), slug control (20%), forced to plant green due to weather (13%). Respondents who ranked “other” in the top 5 were prompted to provide the reasons they planted green or recommended planting green. Reasons listed in no particular order were: “much cooler soil temp,” “bird/squirrel/chipmunk problems,” “less spraying/one pass,” “minimize herbicide,” “reclaim farmland,” “nitrogen fixation from legume CC,” “reduced erosion,” “organic matter,” “less chemical use,” and “[g]reat early planting conditions allows us to plant early May before we terminated.”

Interestingly, slug control did not rank among the top 5 reasons why participants planted green or recommended planting green, while it was among the top 3 reasons listed in a similar survey of the Pennsylvania No Till Alliance in 2013. It is encouraging that perhaps despite underperformance of planting green for slug management specifically (as found in our research and apparently by some farmers who have planted green), there are many other reasons to promote the practice.

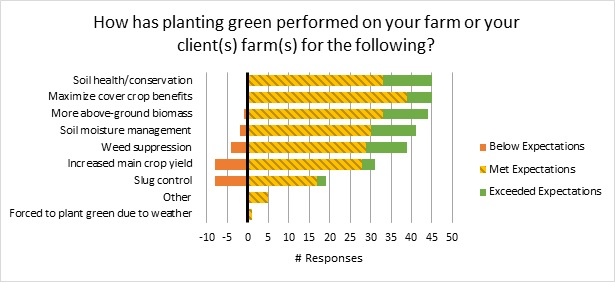

Respondents were then asked whether planting green performed below their expectations, met expectations, or exceeded expectations for the same “reasons for planting green” listed in the previous question. Overall, planting green overwhelmingly met or exceeded expectations. The exceptions which were below expectations included slug control, increased main crop yield, weed suppression, and soil moisture management where 30%, 21%, 9% and 5% of respondents thought planting green fell short of their expectations, respectively.

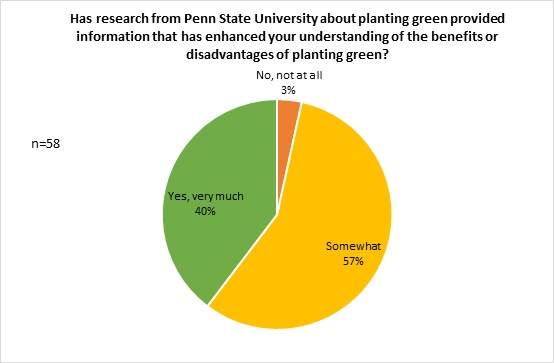

We then asked whether research from Penn State University has provided information that enhanced respondent understanding of the benefits or disadvantages of planting green. An overwhelming majority responded “somewhat,” or “yes, very much,” while only 3% (2 respondents) responded, “no, not at all.”

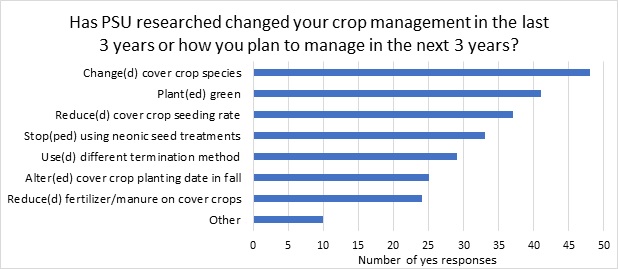

Lastly, we asked participants to indicate all the ways in which Penn State University research has: i. influenced their crop management or recommendations in the past 3 years, and ii. they plan to change their crop management or recommendations in the next 3 years. The most frequently cited change was cover crop species, followed by planting green, reduced cover crop seeding rate, stopped use of neonicotinoid seed treatment, changed cover crop termination method, altered termination method (i.e. roll-crimp + herbicide instead of herbicide only, etc.), altered cover crop planting date, reduced fertility for cover crops, and other. Some categories have more responses than n=44, since some respondents indicated that their management has been altered in the past 3 years and will also be changed for the same category in the next 3 years.

This survey reveals that our planting green research at Penn State University has been effectively communicated to our intended audience: farmers, agency, extension, and ag industry workers interested in soil health and cover crop management. Respondents of this survey have implemented or facilitated implementation of planting green on an estimated 9,180-17,750 acres in Pennsylvania, based on low and high acreage bins from the survey. And, respondents plan to plant green again on most of these acres.

Additional farmers adopt planting green, for a total of 50 farmers.

15

15

December 31, 2018

Completed

December 31, 2018

From March 31, 2018 to December 31, 2018, project results and conclusions were presented and discussed with growers, extension personnel, agency and agricultural industry professionals from Pennsylvania at two outreach events. Events included: Soil Health and Planting Green Field Days (July 31 and August 8), attended by a total of 150 farmers. We estimate the above participant number by suggesting that 10% of farmers participating in our field days within the time frame of this milestone (March 31, 2018-December 31, 2018) will attempt planting green. The number in reality may be far higher, as hundreds of growers and agricultural service providers who participated in our past events likely multiplied this outreach effect and will continue to do so as years pass and more growers successfully use the practice.

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

We had 71 participants at a Soil Health, Cover Crop, and Planting Green Field Day on June 22, 2017. We distributed a survey and had 36 total respondents: 13 growers, 20 ag service providers, and 3 others. We asked participants to note their understanding of planting green before and after the event, with the following choices: non-existent, minimal, moderate, and considerable. Twenty-seven attendees indicated an increase in understanding after the event. The remaining 9 indicated no change, however these had moderate to considerable understanding of the practice before the event.

We asked growers to indicate whether they use certain soil health and cover crop practices. When asked about planting green, 9 responded, "already use, plan to continue;" 3 responded, "plan to start using;" 1 responded, "have in past, will not use again;" and 3 responded, "do not plan to use"

We had 70 participants at a Soil Health and Planting Green Field Day on August 8, 2018. We distributed a survey and had 22 total respondents: 16 growers, 5 ag service providers, and 1 other. We asked participants, "What is the likelihood that this information [planting green research summary] will have a positive impact on your farm management?" 15 respondents were confident or very confident, 4 were only somewhat confident, and 0 were unsure.

We asked growers to indicate whether they use certain soil health and cover crop practices. When asked about planting green, 12 responded, "already use, plan to continue" and 5 responded, "plan to start using," while only 1 person responded, "have in past, will not use again."

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

50

Farmers will delay cover crop termination until (or within days of) cash crop planting, or "plant green"

10,000

The change in practice will enhance soil conservation and health, reduce crop losses to slugs and weeds, and improve cash crop establishment and yields.

50

When weather conditions are favorable around planting (sufficient rainfall), farmers plant their corn and/or soybeans into living green cover crops, or "plant green," allowing cover crops to grow larger and provide better soil protection than killing the cover crop earlier.

We estimate that 46-93 (5-10%) of the 930 farmers who participated in our outreach adopted planting green. If each of these adopted the practice on 100 acres, we estimate that 4,600-9,300 acres of production have been affected by the change.

The change in practice enhanced soil conservation and health. In some cases, the practice did reduce crop losses to slugs and weeds, and improve cash crop establishment and yields.