Final report for LNE20-409R

Project Information

Anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD) is a sustainable approach to pre-plant soil preparation that is used in annual strawberry production systems to reduce the impact of soil-borne diseases and weeds. ASD involves incorporating high levels of carbon into the soil, then saturating and tarping for several weeks. As naturally occurring soil microbes consume the added carbon, they deplete soil oxygen. The toxic by-products of this process kill soil pathogens and possibly damage weed seeds and nematode pests that inhibit plant growth. ASD has not been extensively tested in cold soils or with northeastern perennial June-bearing strawberry systems.

We hypothesized that ASD would be a cost-effective, pre-plant soil treatment that could be used as a replacement for chemical fumigants and fungicide drenches in a perennial strawberry system on northeastern farms. The reduced reliance on chemicals to manage soil-borne diseases and weeds should positively impact soil and environmental health in the long term.

Strawberry farmers located from Maine to western NY participated in the project. These four farmers grow short-day or June-bearing strawberry cultivars; two of them in a traditional matted row system, and two in a raised-bed plasticulture system. One of the farmers was a certified organic farmer who used a high tunnel to protect the matted rows of strawberries.

Three different carbon treatments were applied on all farms. This included alfalfa meal, Brassicaceous seed meal, and dried molasses. All farms had a control treatment which was a non-carbon source, tarped treatment. On three of the farms, we also included the farm-level pre-plant control which included pre-plant soil fumigation, pre-plant soil fungicide drench, and pre-plant biofumigation.

In this project, we evaluated plant health, weed pressure, fruit yield, soil quality, and longevity of ASD effects for all the experimental treatments and the farm control. Our plot design was a randomized complete block. Expenses were tracked on all farms.

Our results are encouraging but nuanced. We did find that ASD treatments resulted in as many or more positive results as did the chemical fumigation, chemical fungicide, and biofumigant treatments. However, they were not statistically different than the tarped control treatment. Weed control in the plasticulture systems is obviously better than in open fields, but the pre-plant tarping for matted row relieved the weed pressure during the first year and likely had a lasting impact for the following production year.

The impact on soil health is still being evaluated. Three years is too short a duration for a full evaluation, but slight changes were noticed in two fields including compaction parameters and microbial activity.

The cost of using ASD is competitive with the chemical fumigants and fungicide drenches. When used in a plasticulture system that already has a plastic mulch ‘tarp’, ASD is cost-effective.

We found it challenging to keep the soil at field saturation, and our soil temperature may have gotten too high at one location.

During this project, the research team presented information and data at eight workshops and conferences across the northeast. We have also written newsletter articles and are currently working on submitting a paper to a peer-reviewed journal in 2024. We used social media during the project to help inform farmers of the ongoing fieldwork.

This project will test the cost effectiveness and utility of anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD) using several different carbon sources in northeastern perennial June-bearing (JB) strawberry systems. Effective, sustainable control of soil borne disease, nematodes and weeds in matted row or plasticulture strawberry systems will encourage improved yields, reduce herbicide and fungicide reliance and support the farmers that are using a strawberry production system that is unique to northern and central regions of the United States.

Strawberries are an important, high-value crop on diversified northeast fruit and vegetable farms. Since 2005, strawberry acreage/production has dropped by more than 50% in New York state, resulting in market share loss while consumer interest in local produce rises. Recent inquiry into strawberry production barriers revealed 41% of farms surveyed in eastern NY had root disease or nematodes that impeded productivity while 28% of those same farms were limited by weed pressure. Soil-borne disease management requires long crop rotations which are challenging to farmers with a limited land base and known chemical and biological control methods are relatively ineffective at controlling soil borne disease - especially when compared to historical chemical fumigation approaches.

Anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD) is a sustainable approach to pre-plant soil preparation that is used in annual strawberry production systems to reduce the impact of soil-borne diseases and weeds. ASD involves incorporating high levels of carbon into the soil, then saturating and tarping for several weeks. As naturally occurring soil microbes consume the added carbon, they deplete soil oxygen. The toxic by-products of this process kill soil pathogens and possibly damage weed seeds and nematode pests that inhibit plant growth. ASD has not been extensively tested in cold soils or with northeastern perennial June-bearing strawberry systems.

We hypothesized that ASD would be a cost-effective, pre-plant soil treatment that could be used as a replacement for chemical fumigants and fungicide drenches in a perennial strawberry system on northeastern farms. The reduced reliance on chemicals to manage soil-borne diseases and weeds should positively impact soil and environmental health in the long term.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

We hypothesize:

• That anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD) will control soil borne disease fungi (including, R. solani, Fusarium spp. and Verticillium spp.), nematode and weed pests of JB perennial plasticulture and/or matted row strawberries grown in cool northeast US soils.

• That ASD will have no negative impact on soil health.

• That the carbon source used during ASD does impact the level of pest control.

• That the cost vs. benefit of ASD compared to current pre-plant strawberry production practices should not discourage adoption of ASD as a management practice to control soil borne pests in perennial strawberry systems.

Trials were established on four farms in the spring of 2021, one in Western NY, two in Eastern NY and one in Maine. The two Eastern NY locations were established as matted row strawberry systems and the Western NY and Maine locations were established on black plastic mulch.

May 26 –Underhill Farm, Western NY; May 26 –Six Rivers Farm, Maine

Strawberries were ordered and sourced from Nourse Farms in South Deerfield, Mass. Jewel was used on both Eastern NY farms. Cavendish was used on the Maine farm and Galletta was used in Western NY.

As strawberry plants were received, sub-samples were sent to Dr. Kerik Cox for evaluation of disease and other potential issues arriving on the plants from the nursery.

Treatments include:

- Control

- Brassica Seed Meal @ 4.5 Tons/acre - all 4 farms

- Alfalfa Seed Meal @ 9 Tons/acre - all 4 farms

- Dried Molasses @ 9 Tons/acre - all 4 farms

- Ridomil Drench (Western NY location only) - growers rate

- Grower Standard Fumigant (one Eastern NY location only) - applied the fall before

- Mustard Cover Crop Biofumigant (one Eastern NY location only) - seeding rate?

In Eastern NY, the two trial locations were plowed and disked in preparation for the trial by the farmers. After this, soil samples were taken and sent to the Cornell Soil Health Testing Laboratory for Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health. CSHT sample dates were: May 20, 2021 –Ariel Farm, Saratoga County, NY; May 21 –Hand Farm, Washington County, NY. On May 24 and 25, the treatment materials were applied to the trial in repeated randomized plots of 50' lengths in amounts specific to each treatment. The farmers disked in the treatments and drip tape was laid and turned on. Silage tarps were laid over the entire trial area and secured with weights. The silage tarps were left in place until temperatures under the plastic reached a minimum of 100 degrees. For the mustard biofumigant treatment, the seed was sown on May 25 and irrigated. The tarps were removed on June 17 and the plots were left to off-gas. On June 23, Jewel bare root strawberries were planted into the treatment plots, one farm using a strawberry planter set at 18 inches in row and one farm by hand at 20 inches in row. For the mustard biofumigant treatment, the crop was terminated and incorporated by rototilling at the slowest speed on July 2nd and left to decompose. The bare root strawberries were planted by hand on July 8th. Weed evaluations were done on August 10th, counting the number of broadleaf and grass weeds in 3 square feet twice in each plot and identifying specific species as well as a visual disease evaluation. Plant samples were collected in early September and send to Dr. Kerik Cox for evaluation of disease and other issues in the first growing season.

In Western NY, the treatments were laid out on May 26, with the grower covering the treatments with black plastic mulch and irrigating. After three weeks or so, the holes were poked in the plastic to let the treatments off-gas and bare root strawberries were planted in by the grower. In the first year of the ASD trial at Underhill, we evaluated 3 ASD carbon sources (brassica seed meal, molasses, alfalfa seed meal) against a positive control (Ridomil Gold SL soil drip) and a negative control (no treatment). All plots were grown as plasticulture, June-bearing strawberries 'Galletta." Initially, strawberries in the ASD treatments appeared to have some nutrition issues and had small, chlorotic leaves. By mid-summer they grew out of this and had green leaves. Weeds were an issue in this planting, and the ASD didn't seem to do much to prevent weed issues.

Plant health was evaluated twice in the growing season. In both evaluations, Ridomil Gold SL-treated plots had the most healthy plants, but this may have been compounded by the positioning of the Ridomil Gold treatment-- on the border of the field, where weed pressure was reduced due to neighboring plots. On the second plant health evaluation, plant health declined across all treatments. Alfalfa seed meal was the second-best treatment, after Ridomil Gold. While brassicas have a track record of improving soil health as a cover crop, using them as an ASD carbon source did not seem to provide good results-- the plant health in those treatments was worse than the negative control that receives no treatment.

As for the grower, his opinion of Ridomil Gold is very high, although he is interested in sustainable means to prepare soil for strawberries. In a different strawberry planting, he used Ridomil Gold in the autumn, and those fields looked really good. I am hoping we'll see more positives from the ASD treatments as we can collect more comprehensive data next year.

2022 and 2023 Growing Season Data Collection Summary

- Assess plants vigor after pulling back the mulch (April)

- The Maine farm only kept the plants a second production year so that we could view them. There was some fruit, but it was very sparse. The planting was tilled in right after harvest.

- The western NY farm also did not keep their plants after harvest, although we were able to get some data before it was tilled.

- One matted row farm had very poor re-growth after the second winter. We took all data, but the problem was throughout the planting and not just in our plot.

- Weed Assessment – should be done before renovation – during harvest preferred. Within 6 square foot grid, count weeds, classify them as grass or broadleaf and identify them as best you can. Do this in each rep. We are not harvesting the weeds.

- During harvest –

- Fruit assessments

- Fruit ‘type’- 4 fully ripe, primary fruit were harvested from each treatment rep. The berries were then ranked for typiness (Yes or No) as described by variety worksheet.

- Fruit Size - Using the same 4 fruit from each rep – measure width, length and weigh the berries

- Fruit Brix - Using refractometer, measure brix of berry juice from berries collected

- We also did a Subjective flavor rating

- Fruit assessments

- Miscellaneous observations

- Note observations of pest problems – insect and disease – during harvest

- Note the start date of commercial harvest in the plots and if they differ from one another.

- Note harvest duration (end of picking date).

- Post-renovation – foliar nutrient analysis.

- Collect 10-12 full trifoliate leaves from each replication. Combine the reps for each treatment and send in leaves for all 4 treatments plus additional treatment if you have one. Rinse quickly with distilled water and spin dry or let air dry. The leaves should be put in paper bags to ship.

- Visual plant assessment – 1-4 rating for each plant in each rep. This was done when foliar samples were gathered in early to mid-August.

- Destructive plant samples - mid-August to early September.

- In 2022 3 plant samples were taken from each rep. on each farm and send to Cornell Diagnostic Lab for evaluation. In 2023, the two plasticulture farms removed plants after fruiting. They did not renovate the plantings. The matted row farms renovated, but one farm had such poor plants that some reps were unable to gather 3 samples. And upon delivery, these plants had almost completely died.

- Soil health sample - late September or early October.

- Soil Health test samples were gathered and submitted to Cornell lab – We are using the Standard PLUS sample at $130/sample. For each farm gather 1 sample for each of the 4 treatments. For information and instructions on soil sampling protocol see https://soilhealth.cals.cornell.edu/testing-services/comprehensive-soil-health-assessment/

In addition to the field data collected, Elizabeth Higgins has been working with growers to determine their average cost of production. We have been collecting cost of treatments and she will assemble the change in cost of production for treatments in a report.

Summary of Weed Control Findings for Farms

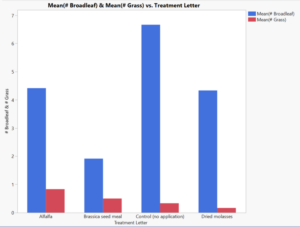

Weed Summary –Weeds were counted and classified as broadleaf or grasses. Figure 1 shows that in the matted row planting on Farm #1, the Brassica Seed Meal treatment resulted in significantly fewer emerged broadleaf weeds, than did the other two Carbon treatments, but insignificant differences between the numbers of emerged grass weeds between the treatments including the control.

Figure 1: Mean # of Emerged Weeds across 3 seasons at Matted Row Farm #1

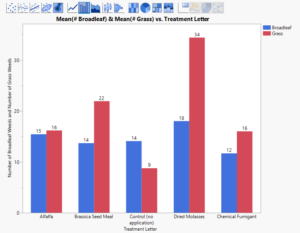

Figure 2 shows that in matted row culture on Farm #2, the Dried Molasses treatment resulted in significantly more emerged grass seedlings throughout 3 seasons, than did the other carbon treatments including the chemical fumigant and the control.

Figure 2

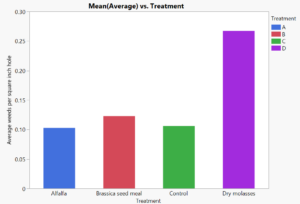

Likewise, Figure 3 indicates that dried molasses may have contributed to greater total weed emergence in planting holes than the other carbon sources or the control.

Figure 3: Mean # of Emerged Weeds during one season on the Plasticulture system at Farm #3

The big challenge for understanding how well the ASD carbon treatments worked is that we didn’t leave a non-tarped control. We are unsure if the ASD process caused the reduction in weed emergence or if was it simply the effect of tarping.

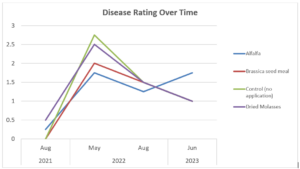

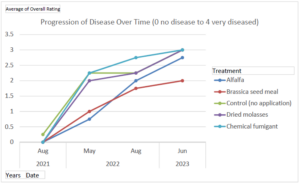

Plant Health Rating Summaries

These plant health ratings were visual rankings of overall plant health and vigor. They included foliar and root disease symptoms, possible impacts due to poor overwintering, predation by insects, competition from weeds etc.

Figure 4: Farm 1 Plant Health and Vigor Ratings over Three Seasons; 0 = excellent vigor, 4 = very poor vigor

Farm 1, a matted row, bare ground conventional farm showed the best plant vigor in the brassica seed meal and control treatments during the first year, then by spring year 2, the control had the worst ratings. All treatment ratings improved during the second year, with an uptick in incidence of poor plant health in the alfalfa treatment.

Figure 5: Farm 2 Plant Health and Vigor Ratings over three seasons; 0 = excellent vigor, 4 = very poor vigor

Farm 2 ratings were more linear over the three years. Vigor declined with each date. The plants in the chemical fumigation treatment were slightly more stressed than other treatments. Brassica seed meal treatment had plants with slightly more vigor.

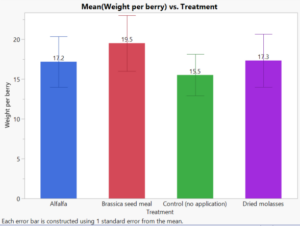

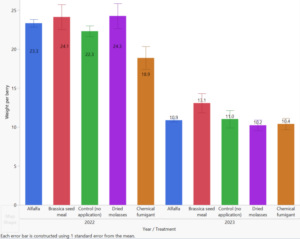

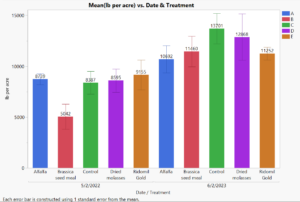

Berry Quality and Weight

Berries were weighed, and evaluated for cultivar characteristics, and Brix was determined to ensure that ASD treatments did not negatively impact fruit quality. Both Farm 1 and 2 grew ‘Jewel’ and had similar individual berry weight (grams) trends for all treatments. Farm 2 berry weights were greater than Farm 1. During the second season, berry weight diminished significantly, likely due to the loss of primary buds in a spring frost event.

Figure 6: Farm 1 Mean Berry weight per treatment

Figure 7: Farm 2 - Mean berry weight for treatments over two season

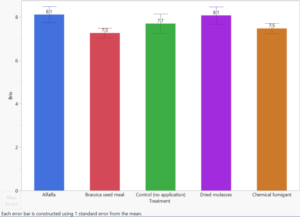

Fruit Quality

Figure 8: Farm 2 Berry Quality, measured in Brix

There did not appear to be any differences in brix as a measure of fruit quality. This was true across treatments including the control, all 3 carbon ASD treatments and the chemical fumigant.

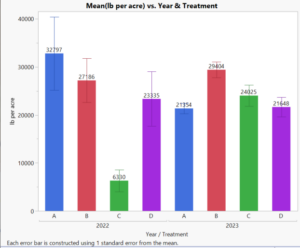

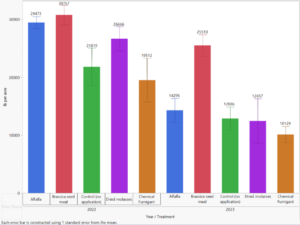

Estimated Yield

Yield was predicted by counting primary, secondary and tertiary flowers during full bloom.

Figure 9: Estimate Yield over two seasons at Farm 1

Estimated yield for all 3 carbon treatments was significantly greater than the control during the first harvest year at Farm 1. During second harvest year only the Brassica Seed Meal treatment showed greater yield potential than the first year. All other treatments showed less potential fruit.

Figure 10: Estimated Yield over two seasons on Farm 2

At Farm 2, a similar trend was exhibited, with all ASD treatments showing greater yield potential than the control. The only treatment with less yield potential was the chemical fumigant. As in Farm 1, this relationship vanished during the second harvest year. Brassica meal treatment was significantly higher than all other treatments, but all treatments yield potential diminished the second year.

Figure 11: Estimated Yield on Farm 4 over two seasons

Farm 4, a conventional raised-bed, plasticulture system had a different trajectory. The Brassica treatment had the lowest estimated yield of all treatments including control and fungicide treatment during first year. All treatments improved during year 2 with the control showing the greatest potential yield.

Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation may have a place in organic and conventional strawberry production practices in the Northeast, but this research project does not conclusively prove that it holds significant benefits beyond existing best management protocols when trying to control soil borne diseases.

The research team is still trying to analyze data - most significantly the impact that ASD may have had on overall soil health which was measured using the Cornell Soil Health test. These results are not included yet in this report.

The plant disease and weed pest problems were positively influenced by ASD on one of the farms tested, but the remaining 3 farms showed no significant positive impact from the practice. ASD did not perform in a less positive manner than the control or the biofumigant, chemical fumigant or fungicide drench, but it wasn't clearly a better approach to pest control in strawberries.

More work needs to be done to better understand the nuances of ASD as a means to improve strawberry productivity. More attention to the actual process needs to be paid in future projects. For instance, measuring field capacity more closely should be done. We were mostly worried about soil temperatures, but that didn't seem to be the problem. Keeping the soil wet during the 3 weeks it was tarped was more problematic.

ASD has the potential to assist strawberry growers, but more work needs to be done as this project did not clearly show an advantage.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Educational activities:

Participation Summary:

Two posts on anaerobic soil disinfestation were posted to the Cornell Berry Blog and distributed through email lists and newsletters.

Video: Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation for High Tunnels

Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation Workshop Summary

One presentation made at Eastern NY Fruit and Veg Conference, February 15, 2022 - 42 growers attended virtually.

One presentation made at Empire State Producers EXPO, January 17, 2022 - 67 growers attended virtually.

A presentation at the New England Fruit IPM meeting on October 25, 2022 - 34 fruit extension and faculty professionals in attendance.

A presentation was made at a Weed Management Workshop in Albany, NY on March 7, 2023. 61 growers were in attendance.

ASD project was discussed at a series of twilight meetings in April and May 2023. There were 17 growers in attendance including 3 Native Americans at the April workshop and 24 growers at the May workshop.

A presentation was made at the Maine Organic Farmers and Growers Association Annual Conference on November 6, 2023. 12 growers were in attendance.

A presentation was made at the New England Veg and Berry Growers annual meeting on January 5, 2024. 56 growers were in attendance.

Mass Veg and Berry Growers_010524

A presentation was made at the Empire Producers EXPO pm January 23, 2024. 49 growers were in attendance.

Learning Outcomes

During discussions about ASD with strawberry growers, especially when we were including discussions of using tarping for controlling weeds, growers were very engaged and responsive. Weed pests are somewhat easier for farmers to assess success, so that makes the strategy that assists that goal more compelling.

There is increased interest in using biofumigation, either in concert with ASD approaches or independently. It appears that nematodes are as much a target of this intervention as are plant diseases.

There is an increased awareness of using cover crops as a way to control soil-borne disease - especially as this study did not identify ASD as being a silver bullet.

Smaller, organic growers are definitely more interested in ASD and tarping as pest control strategies, and this might be due to land availability that limits the crop rotation capacity.

In general, growers are still interested in learning about techniques that can reduce chemical inputs, reduce labor and improve yield. Most strawberry growers confess that they can barely grow enough fruit to meet demand.

Most growers are suspicious of plant quality from nurseries. They understand how difficult it is to produce clean plant stock.

Project Outcomes

This project was ambitious at the start, and despite losing one of our initial collaborating farmers, it remained logistically challenging. For a Novel Approaches project in the future, it might be better to encourage the PI to utilize fewer farms while investigating an unknown production technology. We had 4 farms, only 2 of which were geographically close. Despite much attention to detail, it was still very challenging for the PI to keep track of crop timing that influenced the data collection. Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation remains an intriguing approach to soil disease management. With more attention given to some of the nuances of this procedure, I believe it could have more impact to farmers than we have shown in this study. One of the biggest details is soil saturation. It is very difficult to keep soil at field saturation if we are not receiving rain. Our study showed that soil temperatures were easily able to reach the target temps, and due to hot, dry weather they often were well above the optimal range.

Organic farmers have been incorporating tarping into their production protocols for several years; ASD offers an added benefit as a possible fumigation technique that could easily be an added step to tarping. Unfortunately, we did not leave a NON-tarped control for any of our farms - so we aren't sure how much impact tarping had vs the impact of ASD.