Final report for LNE21-423

Project Information

Problem and Solution

Forest farming—cultivating edible, medicinal, and other commercially valuable crops under an intact forest canopy—is an agroforestry practice ideal for underutilized forestlands in the Northeast United States. However, barriers such as limited technical assistance, lack of regional coordination, and knowledge gaps in cultivation methods have hindered widespread adoption. This project sought to address these issues by establishing a region-wide community of practice—the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition (NFFC)—leveraging partnerships and implementing research and educational initiatives tailored to the Northeast’s unique forest ecosystems.

Research Approach

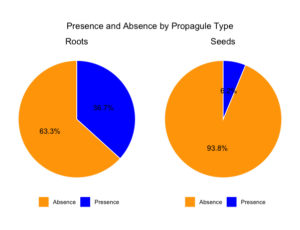

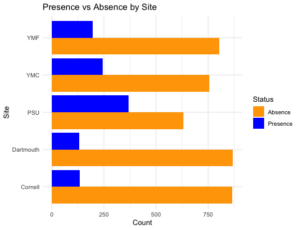

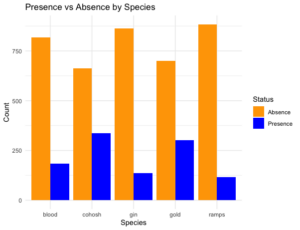

The project conducted experimental plantings at research and demonstration sites across the region. We evaluated the performance of five economically significant forest herb species under varying conditions, including propagation method (seed versus rootlet) and management intensity ("wild-simulated" (low intensity management) versus "woods-grown" (high intensity management)). Data on germination rates, plant establishment, growth, and profitability were collected and analyzed. Our research yielded some key insights into the propagation and management of these forest herbs in a forest farming system, such as the initial higher survival rates of rootlets compared to seeds, and the minimal difference in plant success between wild-simulated and intensive management approaches.

Educational Approach and Farmer Learning Outcomes

Educational activities were integral to the project, with over 20 workshops, numerous training sessions, and a summative multi-day conference held across the region over the lifetime of the project. These workshops, attended by nearly 1,000 farmers over three and a half years, combined field-based and classroom instruction on topics such as species selection, site preparation, planting techniques, and marketing. The project also established a mentorship program pairing experienced farmers with beginners, providing hands-on guidance and support. These efforts resulted in increased farmer confidence and capability to adopt forest farming practices.

Key Results and Farmer Adoption

By the conclusion of the project, the NFFC had successfully engaged 929 farmers and 140 agricultural service providers, far surpassing initial goals. In surveying over the course of the project, حarticipants reported increased knowledge and readiness to establish forest farming enterprises. Research findings supported the viability of wild-simulated forest farming as a cost-effective method, while species-specific insights informed planting strategies for greater success. A significant outcome was the development of a strong, connected community of forest farmers in the Northeast, with several participants initiating or expanding their operations.

Future of the Work

At the conclusion of this funding, region-wide support for the NFFC is significant, with landowners, governmental agencies such as the National Agroforestry Center, NGOs, regional businesses, universities, and other agroforestry coalitions expressing a strong interest in seeing the NFFC's work continue into the future. At our summative conference in September 2024, forest farming stakeholders from across the Northeast US participated in a visioning exercise to help shape the future of our work in the region. With additional grant funding—including a second Northeast SARE grant, project LNE23-469—currently supporting the effort, project leaders will convene a strategic retreat in March 2025 to plan for a future where the NFFC can sustain itself as a standalone NGO, B-Corp, University Center and Program, or some other organizational structure.

Project activities will result in 100 new forest farmers across the Northeast region planting commercially valuable native understory species across 50 acres of forestland, resulting in a profit potential of $500,000 dollars added to privately owned forestland in the region.

Problem and Justification:

The cultivation of commercially-valuable herbs under a forest canopy—an agroforestry practice called forest farming—represents a strategy for increasing economic and ecological diversity on farms across the Northeast. It presents an opportunity to diversify on-farm income streams with low additional labor and costs by converting idle forestland into an economic asset without compromising forest health or timbering potential. The result is greater product diversity, increased farm resilience, and long-term ecological and economic viability (Chittum et al., 2019).

A major barrier to establishing a forest farming enterprise is access to technical information and assistance on topics such as farming techniques, market strategy, regulations, and forest resource inventory and management (Jacobson and Kar, 2013). While coordinated technical assistance is being organized in other regions—exemplified by the Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition (ABFFC), a group founded by Virginia Tech University in 2015 dedicated to the development of forest farming enterprises—this assistance remains sparse and uncoordinated throughout the Northeast U.S.

Meanwhile, prices for forest crops are rising, research and extension around forest farming is improving in quality and quantity, and national support for agroforestry is growing—evidenced by Congresswoman Chellie Pingree’s (D-Maine) proposed 2020 Agricultural Resilience Act, which would expand the National Agroforestry Center through three new regional offices.

Solution and Approach

Our project allowed farmers to meet this opportunity by providing the first region-wide forest farming educational campaign in the Northeast. We built a broad community of practice, centered around small and mid-sized farms with a forested component. This project directly addressed the problem above through strategic regional partnerships, providing the resources and relationships for forest farmers in the Northeast to optimize their operations. This project built off lessons learned in the Appalachian region to bring their knowledge of forest farming to the Northeast.

In-person trainings, the establishment of a peer-to-peer forest farming mentoring network, and the creation of forest farming demonstration sites at strategic locations throughout the region represented the core of our educational campaign. Meanwhile, project research generated baseline data to address understudied ecological, financial, and production questions related to five important forest farmable species with significant profit potential—American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), ramps (Allium triccocum), black cohosh (Actaea racemosa), and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis).

This project represented an opportunity for the Northeast to build on national momentum around forest farming research and education, and it came at a critical time. With a national American Forest Farming Council in the early stages of design, the establishment of a Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition laid a foundation of forest farmers and educational resources in the region.

Works Cited

Adams, A.B., Pontius, J., Galford, G., Gudex-Cross, D., 2019. Simulating forest cover change in the northeastern U.S.: decreasing forest area and increasing fragmentation. Landsc. Ecol. 34, 2401–2419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00896-7

Agroforestry Frequently Asked Questions [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.usda.gov/topics/forestry/agroforestry/agroforestry-frequently-asked-questions (accessed 10.12.20).

Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition, 2020. ABFFC Member Survey (Survey data). Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, VA.

Apsley, D., Carroll, C., 2013. Growing American Ginseng in Ohio: Site Preparation and Planting Using the Wild-Simulated Approach [WWW Document]. Ohioline Ohio State Univ. Ext. URL https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/F-57 (accessed 10.2.20).

Burkhart, E.P., 2011. “Conservation Through Cultivation:” Economic, Socio-Political and Ecological Considerations Regarding the Adoption of ginseng Forest Farming in Pennsylvania.

Burkhart, E.P., Jacobson, M.G., 2009. Transitioning from wild collection to forest cultivation of indigenous medicinal forest plants in eastern North America is constrained by lack of profitability. Agrofor. Syst. 76, 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-008-9173-y

Butler, B.J., 2008. Family Forest Owners of the United States, 2006 (Gen. Tech. Rep. No. NRS-27). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA.

Chittum, H.K., Burkhart, E.P., Munsell, J.F., Kruger, S.D., 2019. A Pathway to a Sustainable Supply of Forest Herbs in the Eastern United States. HerbalGram J. Am. Bot. Counc. 60–77.

Davis, J., Persons, S., 2014. Growing and Marketing Ginseng, Goldenseal and Other Woodland Medicinals, 2nd Edition. ed. New Society Publishers.

Duffy, D.C., Meier, A.J., 1992. Do Appalachian Herbaceous Understories Ever Recover from Clearcutting? Conserv. Biol. 6, 6.

Filyaw, T., Sheban, K., 2015. Restoring Populations of American Ginseng, Goldenseal, and Ramps on the Wayne National Forest – Round Two (Final Grant Report to the National Forest Foundation No. AH-903). Rural Action.

Gilliam, F.S. (Ed.), 2014. The Herbaceous Layer in Forests of Eastern North America. Oxford University Press.

Hamilton, J., 2017. Wild Simulated Ginseng Production.

Holmes, M.A., Matlack, G.R., 2018. Assembling the forest herb community after abandonment from agriculture: Long-term successional dynamics differ with land-use history. J. Ecol. 106, 2121–2131. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12970

Jacobson, M., Kar, S., 2013. Extent of Agroforestry Extension Programs in the United States. J. Ext. 51.

Kremen, C., Miles, A., 2012. Ecosystem Services in Biologically Diversified versus Conventional Farming Systems: Benefits, Externalities, and Trade-Offs. Ecol. Soc. 17.

Lee, J.C., Strik, B.C., Proctor, J.T.A., 1985. Dormancy and growth of American ginseng as influenced by temperature. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 11, 319.

Li, T.S., Berard, R.G., 1998. Effects of soil moisture on the growth of american ginseng (Panax quinquefolium L.). J. Ginseng Res. 22, 122–125.

Lin, B.B., 2011. Resilience in Agriculture through Crop Diversification: Adaptive Management for Environmental Change. BioScience 61, 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.3.4

Munsell, J., 2017. Seeded and Growing: Sustaining Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Education and Engagement (Grant Report).

Nehring, R., Gillespie, J., Sandretto, C., Hallahan, C., 2009. Small U.S. dairy farms: can they compete? Agric. Econ. 40, 817–825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00418.x

Northeast / Mid-Atlantic Agroforestry [WWW Document], n.d. . Welcome Cap. RCD. URL https://www.capitalrcd.org/nemaagroforestry.html (accessed 10.2.20).

Northern Forest Futures Project [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/futures/dashboard/current/?var=NO_PRIV (accessed 10.2.20).

Ren, F.-C., Liu, T.-C., Liu, H.-Q., Hu, B.-Y., 1993. Influence of zinc on the growth, distribution of elements, and metabolism of one‐year old American ginseng plants. J. Plant Nutr. 16, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904169309364539

Sheban, K., 2019. Importance of Environmental Factors on Plantings of Wild-Simulated American Ginseng [WWW Document]. USDA Sustain. Agric. Res. Educ. SARE. URL https://projects.sare.org/sare_project/gne19-221/ (accessed 10.18.20).

Smith, T., Gillespie, M., Eckl, V., Knepper, J., Reynolds, C.M., 2018. Herbal Supplement Sales in US Increase by 9.4% in 2018. HerbalGram J. Am. Bot. Counc. 62–73.

Smith, T., Kawa, K., Eckl, V., Morton, C., Stredney, R., 2017. HerbalGram: Herbal Supplement Sales in US Increase 7.7% in 2016 Consumer preferences shifting toward ingredients with general wellness benefits, driving growth of adaptogens and digestive health products. HerbalGram J. Am. Bot. Counc. 56–65.

Trozzo, K., Munsell, J., Niewolny, K., Chamberlain, J.L., 2019. Forest Food and Medicine in Contemporary Appalachia. Southeast. Geogr. 59, 52–76. https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2019.0005

United Plant Savers, 2018. Species At-Risk List. United Plant Savers. URL https://unitedplantsavers.org/species-at-risk-list/ (accessed 10.13.20).

USDA Forest Service, 2005. A Snapshot of the Northeastern Forests [WWW Document]. Northeast. Area State Priv. For. URL http://www.northeasternforests.org/content/northeastern_forests (accessed 10.2.20).

Valdivia, C., Barbieri, C., Gold, M.A., 2012. Between Forestry and Farming: Policy and Environmental Implications of the Barriers to Agroforestry Adoption. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. Agroeconomie 60, 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7976.2012.01248.x

Vaughan, R.C., Munsell, J.F., Chamberlain, J.L., 2013. Opportunities for Enhancing Nontimber Forest Products Management in the United States. J. For. 111, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.10-106

Workman, S.W., Bannister, M.E., Nair, P.K.R., 2003. Agroforestry potential in the southeastern United States: perceptions of landowners and extension professionals. Agrofor. Syst. 59, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026193204801

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

We will establish growth and yield trials for five commercially valuable forest understory species under different propagation methods—from seed and from rootlet transplant—and management regimes, with labor and inputs ranging from minimal to intensive. Prior research suggests as labor and inputs increase, plant growth and yields increase; however, given varying price points for study species the increase in production may not mean increased profitability.

In this project we will 1) assess the commercial production of understory herbs in a Northeast forest farming context, and 2) determine the most profitable propagation method and management regime on a species-by-species basis.

Original Research Description

This research will provide important ecological, financial, and production data on five species with significant profit potential—American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), ramps (Allium triccocum), black cohosh (Actaea racemosa), and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Little is known regarding rates of survival, establishment, and growth and yield for these species under different management systems, especially in the Northeast region. This research will help farmers make informed decisions about growing methods, costs, and revenue ratios under different management intensity regimes.

Farmer input:

Farmers’ input was integrated throughout the design of this research: A) our research questions are a direct response to survey data from hundreds of farmers (Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition, 2020); B) the research design of this project builds on research PI-Sheban conducted with American Ginseng Pharm (Sheban, 2019); and C) we conducted numerous consultations with project advisory board members.

Treatments:

Our project treatments were chosen in direct response to forest farmers input. When asked “what forest farming topics are you most interested in?” in a survey of nearly 500 forest farmers, the top two answers were: 1) Forest management for understory crops and 2) Plant propagation. Therefore, these are the primary treatments examined in our research.

Forest management: The question of whether a “wild-simulated” approach to forest farming is the most practical and cost-effective strategy for landowners has not been comprehensively studied. Wild-simulated production requires the fewest inputs of time, labor, and materials. And in the case of ginseng—which has a unique market in East Asia for wild-appearing roots—it often results in the highest-value product. Thus this approach to forest farming is often recommended to small-scale operations (Apsley and Carroll, 2013). However, modifying the local growing conditions—by removing competing understory and midstory plants, tilling the first inch of the soil, applying fertilizer—can result in faster growth rates and larger plants, potentially increasing the value of a forest planting. The majority of scaled forest farms modify the growing environment in some way. Establishing the difference in establishment, growth, and yields under these different management regimes—from intensive commercial-style to wild-simulated production—and tracking costs and profits will help beginning and experienced forest farmers decide what growing methodology is right for their operation.

Plant propagation: There have been no formalized studies examining the differences in establishment rates of forest herbs grown by seed and by rootlet in forest farming operations. The information available is often focused on container growth for horticultural crops and not for in-situ forest farming operations, representing very different systems. Anecdotal experience and horticultural guides suggest that propagation success and establishment vary by species. Outplanting rootlets is a more common approach to propagation for most species because of the assumption of better establishment, although it is more costly and time intensive. Seed establishment in ramps can result in germination rates of up to 90% (Filyaw and Sheban, 2015) showing huge cost saving potential. Having a species-specific understanding of which method is more effective will help forest farmers minimize costs as well as help nurseries growing planting stock invest in the material that is the most valuable for their consumers.

Methods:

We will conduct experimental plantings of the five target species at six research and demonstration farms across the Northeast region (Figure 1). These sites include the Yale-Myers Forest in northeast Connecticut; American Ginseng Pharm in the Catskill region of New York; the property of farmer Stephen Prinn in Northeast Connecticut; Penn State University’s Shaver’s Creek in Central Pennsylvania; the Yew Mountain Center in Southeast West Virginia; and Cornell’s Uihlein Forest in Northern New York. Additionally, as a comparison site, we will conduct a seventh planting under shade cloth in a hoop house (i.e. intensive commercial-style production) at Penn State’s Beaver Campus in Eastern Pennsylvania.

For our forested plots, we will use a blocked two-by-two factorial design (Figure 2). The first treatment level is planting stock type (seeds (S) or rootlets (R)). The second treatment level is management intensity (wild-simulated (WS) or intensively managed (IM). The fully factorial design results in four unique conditions (four plots) for each block:

- propagated by seed, wild-simulated management (S-WS)

- propagated by rootlet, wild-simulated management (R-WS)

- propagated by seed, intensive management (S-IM)

- propagated by rootlet, intensive management (R-IM)

At each forested research site there will be five blocks, randomly distributed, each containing a replicate of the above four treatments (4 plots per block x 5 replications at each site x 6 sites = 120 plots per species). The same experimental design will be done with each of the five species as independent experiments for a total of 100 plots per site (Figure 3), and 600 plots across all sites.

We will use English units for this research because these are most used by forest farmers; thus, these are the units in which we will be communicating our findings. Treatment Plots are 3’x3’, where one of the four treatment combinations will be applied at the entire plot except a small 6” buffer on all sides adjacent to the other plots. Each plot will be planted with either 4 seeds or 4 rootlets in the 1 sq. ft center of each treatment plot, to mitigate edge effects.

All plots will be established in the fall of 2021. Wild-simulated plots will receive no management beyond planting and initial watering. In the intensively managed plots we will remove any plants within or immediately adjacent to the plot and cultivate the first four inches of the soil before planting. Once planted, plots will be mulched using small-grain straw, weeded twice a season, and fertilized with gypsum in Year 1 to achieve the optimum levels of calcium and pH (Davis and Persons, 2014).

The comparison plot will be planted in raised beds under artificial shade cloth in a 70-ft long hoop house in eastern Pennsylvania. Plants will be weeded, watered, fertilized, and treated with fungicide on a weekly basis. This site will provide a financial and production comparison to the forest farming systems being compared in our study.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We will choose planting sites through coordination with the farm partner. Once planting sites are selected, we will take baseline environmental measurements at each plot: we will measure percent canopy coverage using a spherical densiometer; soil moisture using a Hydrosense moisture meter; and collect composite soil samples for nutrient analysis.

We will collect data on germination, plant establishment (mortality and survival) and plant size, we will note any herbivory or disease we observe, as well as environmental conditions (sunlight, soil nutrients and water content) three times during each growing season: May, July, and September. At the end of the experiment we will harvest a sub-sample of the plots and measure final biomass production.

We will used generalized linear mixed effect models to examine the importance of each of our farming intensity factors as well as their interaction and environmental variables of light and moisture as our response variables with block and site as random effects. Our response variables include survival rate/establishment, plant growth, harvest biomass.

We will track costs by species and treatment and calculate potential income based on biomass harvest in order to generate profitability projections between treatment combinations. We will compile a database and provide records of where all plant material is sourced from and sold.

Project update after Year 1

To date we have made significant progress on the project, and are on track in accordance with proposed project milestones. The bulk of work thus far has focused on the coordination of project partners, the procurement of planting stock, and the establishment of Research & Demonstration (R&D) sites across the Northeast region. Spring and summer months were spent identifying planting stock suppliers and monitoring the supply for target species, which are not always readily available. Planting stock for five target species—American ginseng, goldenseal, ramps, black cohosh, and bloodroot—was sourced from multiple providers, in response to availability. Planting stock sourcing was as follows

- Ginseng seed from Rural Action

- Ginseng roots from Harding’s ginseng

- Ramp bulbs from Wild West Virginia Ramps

- Black cohosh, bloodroot, and goldenseal roots from Loess Roots

- Black cohosh, bloodroot, goldenseal, and ramp seed from Prairie Moon Nursery

The summer months were also spent coordinating with R&D sites and project partners, to select windows for planting during the fall. To date, five R&D sites have been planted

- Oct 16-17, Yale-Myers Forest in Eastford, CT

- Oct 19-20, Dartmouth Forest in Hanover, NH

- Oct 21-22, Cornell University’s Uihlein Maple Syrup Research Forest in Lake Placid, NY

- Nov 18-19, Penn State’s Shaver’s Creek Forest, Petersburg, PA

- Nov 29 – Dec 3, Yew Mountain Center in Hillsboro, WV

There are a few important changes to the original scope of work to note when it comes to R&D sites.

- We dropped one of our initial planting sites, American Ginseng Pharm in the Catskill region of NY, due to internal complications within the business structure. In place of this site, we planted at the Dartmouth University school forest in Hanover, NH. We believe this is a strong substitution for a R&D site given its location in the region, the resources of the university, and a collaboration with the agroecology lab of Dr. Theresa Ong.

- Ultimately we decided not to conduct an experimental planting of project target species under a hoop house in eastern Pennsylvania. This was due in part to challenges with the site selected for this project activity, and was in part based on discussions with advisory board member Dr. Eric Burkhart, who recommended using project funds to instead erect an experimental deer fence around the R&D site at Shaver’s Creek. As deer are a major pest in plantings of forest understory herbs, deer fencing will allow us to compare growth and yield under conditions of deer pressure with conditions that are deer free. We believe this reallocation falls within the spirit of the award and will let us answer questions critical to forest farmers in the region.

- We decided to postpone our planting site at farmer Steve Prinn’s property in Eastford, CT. We plan to plant this site in the spring of 2022. In addition we are in conversation with Emily Ruff, the Director of Sage Mountain Botanical Sanctuary in East Barre, VT, about establishing an R&D site on the 600-acre learning forest where she and her staff conduct education around forest biodiversity, forest understory herbs, and agroforestry systems.

Thus the two additional R&D sites we plan to plant in the spring of 2022 are:

- Forest farmer Steve Prinn's property in Eastford, CT

- Sage Mountain Botanical Sanctuary in East Barre, VT

Project update after Year 2:

Two updates regarding our R&D sites following our second year of the grant are as follows:

- We did not end up planting additional R&D sites at Steve Prinn's property in Eastford, CT and at Sage Botanical Sanctuary in East Barre, VT. In the spring of 2022 we did host two separate workshops at these locations, and conducted forest botanical plantings with workshop participants. However, due to logistical difficulties around including workshop attendees in planting efforts we opted not to design plantings in same layout as R&D sites. However, these sites can still be monitored for growth and establishment of plantings which can provide supplemental data.

- Due to low initial germination of plantings from seed in R&D sites we have opted to replant seed plantings at a higher seed density at one of our R&D sites (Yale Myers Forest). We are in the process of conducting this planting in early January and have designed it in such a way that we will be able to distinguish Year 2 seed plantings from Year 1 seed plantings.

In the summer of 2022, we conducted our first round of data collection on all 5 of our R&D sites. This involved monitoring and noting germination rate and establishment rate of both seed and root plantings. We also collected data on deer browse rates and plantings that reached sexual maturity (flowers/fruits). While collecting data we also did a second round of weeding around the "managed" plantings. We presented our initial data at the Society of American Foresters (SAF) National Conference in Baltimore, MD in the fall of 2022 (see the poster below).

In the spring of 2023 we plan to conduct our second round of data collection. During this round we will also collect baseline environmental data on each R&D site including canopy cover measurements, overstory species analysis, and soil samples.

Project update after Year 3

Sites were visited and weeded in year 3 and we made observations on plantings but no data was formally collected; During 2022 and 2023 project member Karam Sheban transitioned roles into a PhD at Yale, and 2023 was spent working with Dr. Marlyse Duguid (project PI) and Dr. Mark Bradford to map out data collection in the summer of 2024 to include baseline environmental data on each R&D site including canopy cover measurements, overstory species analysis, and soil samples. With a project extension and new formal end date of November, 2024 project leaders will use the upcoming summer of 2024 (the third growing season) as a culminating research field season. Planning is underway, with project member Karam Sheban coordinating with the Ingalls Field Ecology Program (see link for a description of NFFC work), a summer internship program for undergraduate students from across the world, to provide students with exposure to agroforestry, field research methods, and data collection/analysis.

Final update

In the summer of 2024, all research sites were revisited for an additional round of monitoring data; project member Karam Sheban was assisted by two master's student field researchers in visited sites, weeding our research plots, and collecting data on survival and life stage for all our plants (see photos below).

While we initially proposed to harvest the plants from our experimental research sites, our research team made the decision to keep the plants in the ground until after their fifth year of growth for harvest data that more accurately reflects a typical timeline for forest farming. Concurrent forest farming research being conducted by project PD Duiguid and Project Manager Sheban is working on developing allometric methods for using leaf area as a proxy measurement for root size, which could allow us to use non-destructive methods to measure our plant growth; the added value of monitoring plants over a longer timeline (forest farmers often leave a crop in the ground for up to 10 years) is significant, and our team has ongoing student capacity to continue collecting data through 2026 (end of fifth growing season) and beyond.

Project update after Year 2

Initial findings showed much higher establishment rates with plantings from root compared to plantings from seed across all sites. However, this result is somewhat expected after one year since most species exhibit an ecological trait called double seed dormancy by which seeds can take multiple years to germinate. As such, these year one findings should not be considered fully accurate. So far, goldenseal and black cohosh have showed the highest overall success rates at establishing across all sites. We also found that plantings of ramps had died back earlier than other species, which lead us to leave out collecting data on ramps during year 1. We will plan to go back earlier in the season in our second round of data collection to ensure that we are early enough to collect data on ramp plantings as well.

Project update after Year 4

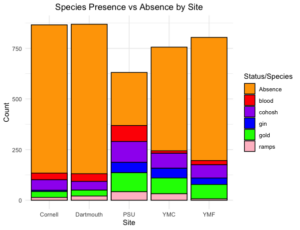

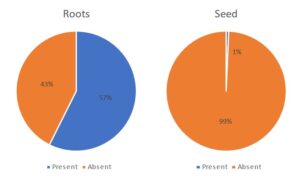

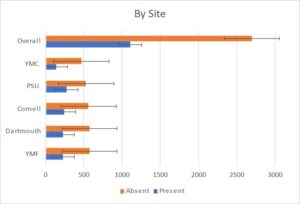

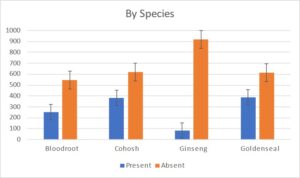

Following up on the findings after Year 2, we see some clear trends emerging. The proportion of seeds that germinated and were present across all sites increased over the past two years, suggesting that many of the seeds we planted had not germinated; the presence of plants in our seed plots increased from 1% of overall plots to 6%. Meanwhile, root plots showed a decrease in survival, with 37% of plots having a plant present at the time of data collection in the summer of 2024. Looking at the distribution of plants by site and by species we see that this overall decrease of plants did not take place evenly across our different sites. During data collection in the summer of 2024 there was an observable divergence of sites; in particular, plants at the Cornell site seemed to be doing poorly while the Penn State site seemed to be thriving, increasing in both size and number. Looking at the data between years 2 and 4, the Penn State (PSU) site and the Yew Mountain Center (YMC) overall saw an increase in observable plants while the other three sites (Yale Myers Forest (YMF), Dartmouth, and Cornell) saw a decrease. In that same span of time, the proportion of presence by species stayed the same, with black cohosh and goldenseal doing better, and ginseng, ramps, and bloodroot underperforming by comparison.

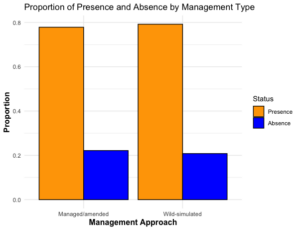

Additionally, looking at the proportions of the plant presence and absence broken down by management approach (wild-simulated vs woods-grown), we don't see a significant difference.

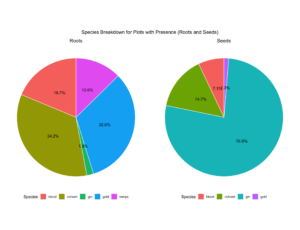

Meanwhile, looking at the proportion of different species within the plots that had plants present by site and by planting stock type reveal variable success by species. Goldenseal and black cohosh transplanted as roots proportionally well, while ginseng seed was by far the most successful. The success of different species varied by site as well.

With data from three growing seasons, we can draw some preliminary conclusions from our data as this project comes to a close.

- Planting stock type has a significant effect on the initial "success" of a planting. Between the plots we planted with seeds and roots, our root plots had a much higher initial survival rate. After year 2, this was nearly 60%, while only 1% of our seed plots germinated the spring following planting. However, this trend began to flip as time went on, and by Year 4 the proportion of seed plots with plants present had increased while the proportion of root plots with plants present decreased. For farmers considering whether to source seeds or roots, the initial higher emergence rate of roots may be appealing, but over the long-term our data suggests the establishment gap between planting stock types may shrink. Given the much higher cost of buying roots to plant, seed may be an attractive option for forest farmers; the relatively low survival rate may not be a problem given that a farmer can just plant their seed more densely to compensate at little additional cost.

- Management approach had a minimal effect on plant establishment. After three growing seasons, we saw almost no difference between plots planting using a wild-simulated approach those planted using a woods-grown approach, where we tilled the soil, added pelletized gypsum, and weeded plots each year. This suggests that management of plantings in a wooded environment isn't having much of an effect on planting success. Given the extra time, labor, and cost associated with a woods-grown approach to management, our data suggest growers are better off taking a wild-simulated approach to save time and money and achieve similar results.

- Planting site matters. One of the most interesting trends in our data over the lifetime of this project is the relative success of our plantings across different sites. Some of sites saw their plant populations increasing after our initial planting year, while others saw those populations decreasing. The reasons for this are not totally clear, but are likely a combination of 1) site quality and 2) deer pressure. We decided to maintain our plantings in the ground for the time being to continue observing these trends over time, with plans to publish papers from these plots in scientific journals likely when the plants have passed their fifth growing season, and will take soil samples at that time. Site fertility is likely a factor at play, which likely explains the relatively poor performance of the Cornell site (northern latitude with a high incidence of birch and fern in the planting site); but in conversation with the forest managers at each site, it was the sites with the highest deer pressure that saw their populations decreasing in size over time. Most notably, the Penn State site had deer fence around it and saw by far the largest increase in plant presence and size increase. These factors suggest that growers should identify their most fertile planting sites and take steps to deter predators such as deer.

- Diversification is key. The different species we planted performed differently across sites and across planting stock type. In the figures above you can see that certain plants did better when transplanted as roots (e.g. goldenseal and black cohosh) while others performed better when planted as seed (e.g. ginseng). The species we planted performed better and worse at our different sites as well; as an example, bloodroot performed much better at PSU relative to the YMC, our two highest-performing sites. This could be due to site conditions (drier vs. wetter soils, higher vs. lower light levels) or predators having a taste for some plants over others. For the prospective grower, planting a diversity of species allows you to identify which will succeed on your available sites.

Education

Resources developed as a result of this project include:

Forest Farming Production Tool: This excel-based tool allows users to input the NTFPs they are selling, as well as their costs, to model out the profitability of their forest farming operation. It allows users to determine what scenarios would allow for a profitable operation and to decide what variables (price, products, labor, venue of sale) to tweak to increase the financial viability of their operation.

Northeast Forest Farming Conference Videos

Original Educational approach

This project will establish six forest farming research sites across the Northeast region. Four of these will double as educational demonstration sites—the Yale-Myers Forest; the Cornell Uihlein Forest; Penn State’s Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center; and the Yew Mountain Center—which will provide hands-on educational opportunities to address the fundamental knowledge gaps necessary to start a production forest farm.

We will offer nine in-person workshops over the three-year project timeline, with a target of 25 workshop attendees at each event for a total of 225 attendees over the lifetime of the project. Workshops will cover the topics that forest farmers have identified as most critical for establishing an operation (Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition, 2020), and content will be organized from introductory to more advanced material, allowing beginning forest farmers to move through an educational progression—from planning to implementing a forest farm all the way to conducting product sales.

Year 1: Species biology/ecology, site selection and preparation, forest management for NTFPs, and planting techniques

Year 2: Harvesting and drying, value-added processing, and enterprise budget planning for forest farming operations

Year 3: Marketing botanical products, and enrollment in verification programs

Many of these topics will be hands-on and participatory, taught in the field, using project demonstration sites to ground lessons in the physical environment. At project events we will provide printed resources, also available online—some existing and some specific to the Northeast that we create with project funds—that cover the above topics for farmers’ reference through the implementation process. These will be factsheets and cultivation guidebooks. During the project we will create six new educational videos on the above topics, which we will make available on the project website and Facebook page, and upload to the Forest Farming YouTube channel, which already has 170 videos and nearly 20 thousand followers.

Event educators will be project key individuals, advisory board members, and others with topic-specific forest farming expertise in order to address the topics above. All classroom and field sessions will be recorded and made available through the Yale Forest School website and the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition Facebook page to expand the reach of our educational campaign.

Mentorship is the second-most requested service by forest farmers, after in-person workshops. In Project Year 2 we will organize a mentorship program. Interested project farmers will be paired up with an experienced mentor, drawn from a pool of forest farmers in the ABFFC network who have already expressed a willingness to mentor a beginning farmer. Mentors will be compensated for three consultations with their mentee beginning in project Year 2.

We will plug into ABFFC recruitment networks to identify members farming in the Northeast. Additionally, we will draw on the established outreach and extension networks of partnering universities—Yale, Penn State, Cornell—to recruit new forest farmers into the network. We will also recruit members and promote events through state NOFA chapters, the National Young Farmers coalition, state Farm Bureaus, and the cooperative extension networks of regional states.

Currently, we are in the process of recruiting landowners to join the Coalition and begin following our activities through the project website. This will serve as the basis of our landowner network, whom we will advertise educational events to. This will begin in spring of 2022. In addition to the establishment of R&D sites, we have worked with Meghan Bathgate and Jennifer Claydon of Yale’s Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning to design a forest farmer intake survey – this tool allows for crucial data collection on forest farmers and interested forest landowners in the region. Working with Yale students, we have also designed a website to house the intake survey, as well as online resources and an event calendar for the project. The website is currently live and can be found here. A big focus of the project over the next 6 months will be to build our online presence and resources to turn the website into a critical tool and first point of engagement for interested forest farmers in the Northeast. This will entail the creation of new resources, such as educational videos, but also the strategic integration of online tools being created by project partners, such as the Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition.

Project update after Year 2:

The NFFC has launched into holding educational events and workshops since covid restrictions started to ease over the past year. Between the spring of 2022 and the fall of 2023 we have:

- hosted 4 in-person workshops

- participated as a guest speaker at another SARE workshop

- presented our initial research findings at a poster session at the National SAF Conference

- spoke on a panel titled "What foresters need to know about forest farming" at the National SAF Conference

- established a demonstration plot of wild simulated forest botanicals at the Yale-Myers Forest

Our digital reach has also greatly expanded over the last year:

- 175 people have filled out our intake survey, becoming NFFC members while providing valuable data on regional forest farmers' interests, needs, and demographics

- the NFFC website had 1,864 visits in 2022

- our membership has increased to include 366 individuals

- we have conducted multiple online surveys to better understand the forest farming landscape in the Northeast, including a survey focused on understanding forest botanical planting stock shortages (49 responses to date) as well as one focused on understanding the needs of Technical Service Providers in the region (40 responses to date).

- our Instagram account has gained significant traction with 361 followers

Workshops:

Yale-Myers Forest (April 23rd, 2022)

Our first workshop took place at the Yale-Myers Forest and had 56 workshop attendees. The day included an introductory presentation on forest farming given by Karam Sheban, field-based discussions around forest botanical plant ecology and site selection lead by Professor Marlyse Duguid and Walker Cammack, and a forest botanical planting demonstration hosted at forest farmer Steve Prinn's property. Participants were given the opportunity to try planting ginseng, ramps, black cohosh, bloodroot, and goldenseal from both seed and root.

Sage Mountain Botanical Sanctuary (June 4th, 2022)

Our workshop at Sage Mountain fetched over 100 RSVPs but due to site restrictions and sensitive habitat we only had around 20 people attend. The day started with an introductory presentation given by Walker Cammack and was followed by a forest botanical plant walk focused on species identification that was lead by United Plant Savers affiliate Betzy Bancroft. Professor Marlyse Duguid also discussed forest botanical plant ecology with participants. A discussion around how Vermont land-use laws might affect the adoption and practice of forest farming was held by Sage Mountain director Emily Ruff during lunch. Finally, the day was wrapped up with a forest botanical planting demonstration in which participants learned and practiced best planting practices for black cohosh and goldenseal.

Wild Hudson Valley (September 10th, 2022)

This workshop was a collaboration with Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler of Wild Hudson Valley and was restricted to 20 participants due to sensitive habitat. Anna and Justin covered all-things ginseng ecology and cultivation. They provided samples of ginseng products, as well as recently harvested specimens to discuss identification and ecology. Anna and Justin then lead participants through their property while discussing ginseng habitat. The day ended with a hands-on demonstration of planting ginseng by seed. All participants were able to go home with their own 1/4lb bag of ginseng seed to be planted on their own property.

NRCS Training at Yale-Myers Forest (October 24th, 2022)

The NRCS Training was a collaboration between the NFFC and the CT, MA, and RI NRCS departments meant to train NRCS technical service providers in best forest farming practices. 30 NRCS agents from southern New England states attended. This was organized by the NRCS and individuals within the CT NRCS office. A lack of technical service providers with knowledge around forest farming has been identified as one of the biggest barriers to forest farming adoption, so we saw this as a wonderful opportunity to address this issue. The workshop started with a presentation by Walker Cammack on forest farming and the role of NRCS agents in supporting landowners interested in forest farming. The participants than went on a tour of the various forest farming sites at Yale-Myers Forest, including the NFFC R&D site. A discussion and exercise in forest botanical site selection was conducted at the R&D site before the day was finished off with a hands-on ginseng seed planting demonstration.

Speaking Events:

Upper Valley Agroforestry Transition Hub Tour (October 30th, 2022):

We gave and introduction to forest farming at the Dartmouth R&D site during an agroforestry tour that was a part of the curriculum for the Upper Valley Agroforestry Transition Hub's (SARE LNE22-441) farmer cohort.

Society of American Foresters National Conference Poster Session (September 22, 2022):

Karam Sheban and Walker Cammack presented initial research findings and lessons learned from the first year of establishing the NFFC. This also served as an opportunity to network and increase the reach of the NFFC to the national stage.

Society of American Foresters National Conference Forest Farming Panel (September 23, 2022):

Walker Cammack spoke on a panel with John Munsell (of the Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition) on the topic of what foresters need to know about forest farming. The panel was lead by Kate Macfarland (Agroforester for the National Agroforestry Center) and was a well-attended.

Project update after Year 3:

This has been a big year for the NFFC. We hosted four in-person workshops and presented at three conferences, exceeding our goals for the year.

On February 18th, Walker gave a presentation on the NFFC work to a group at NOFA Vermont's 41st Annual winter conference in Burlington, VT, to a group of 70 farmers, forest managers, and technical service providers. Here is a link to the virtual presentation, which we've also posted on Resources tab of our website.

On February 21st, Karam and Walker traveled to Costa Rica to attend and present at the Association for Temperate Agroforestry (AFTA)'s biannual conference, with 31 academics, students, practitioners, and farmers in the room.

On March 27th we gave a presentation to mentors and mentees to inaugurate our mentorship program. We dramatically expanded the mentorship program from its original scope, to include 36 mentees and 11 mentors; so this presentation reached 47 people.

On September 2nd, our partner farm Wild Hudson Valley hosted an NFFC-funded "deep dive" workshop at their farm in the Catskills of New York for 27 attendees. This is the second year in a row Anna and Justin have presented with the NFFC.

On October 2nd Karam did a field presentation for a group of Yale master's students in a temperate agroforestry class at one of our replicated research plantings at the Yale-Myers Forest. There were 18 students present. This was an opportunity to check on research plantings, which revealed some exciting developments, including this seed plot where after two years of no growth, both planted ginseng seeds had germinated.

On October 10th, Karam and Walker hosted a forest farming cultivation workshop at Smokey House in Danby, Vermont, with 20 people in attendance. This event included an indoor presentation as well as a hands-on field component, where attendees planted ginseng and took home ginseng seed.

Between October 25th and 28th, Karam and Walker attended the National Society of American Foresters (SAF) conference in Sacremento, California, where they presented on three years of the NFFC to a packed conference room with 83 people in attendance. While not formally surveyed, this group contained forest landowners, university faculty and staff, professional foresters, and other technical service providers. Outside of the presentation itself, the event was a tremendous networking opportunity, and highlighted the cresting interest in agroforestry among the forestry community.

And finally, on December 7th, Karam presented virtually at the Savanna Institute's 2023 Perennial Farm Gathering on the NFFC work, as part of a group presentation on forest farming, alongside Robin Suggs of Appalachian Sustainable Development and Ingrid West of Misty Dawn Farm. This was the second highest attended session of the entire conference, behind the keynote (Robin Wall Kimmerer), so we felt pretty good about that! There were 161 people in attendance.

Project update after Year 4:

In 2024 we continued to have a diverse set of trainings and events serving farmers and service providers, despite having hit our metrics. In April Karam presented on our research to a group of academics and practitioners at the Society of Ethnobiology in Missouri, with 26 people in attendance. In June, at the request of the National Agroforestry Center, project leaders Karam and Marlyse ran a workshop on forest farming for New England NRCS agents as part of a three-day training for Technical Service Providers on agroforestry practices relevant to the region. This all-day event included both classroom and field sessions.

And finally, in October of 2024 NFFC farmer mentors at Wild Hudson Valley hosted a ginseng wild simulated cultivation workshop for 20 beginning forest farmers, this is the third workshop they have hosted for us and they continue to be popular and overenrolled.

Our biggest event to date for this project was our final wrap-up conference. September 6-8 in Danby, Vermont, we organized and hosted the inaugural Northeast Forest Farming Conference at the Smokey House Center: https://www.smokeyhouse.org/event-details/2024-northeast-forest-farming-conference. We had 150 registered participants and a waiting list. Workshops largely took place in the field, with hands-on learning opportunities complemented by presentations given by expert speakers from the Northeast and from our experienced partners in Appalachia. Workshop topics ranged from species-specific cultivation (e.g. forest planting of ramps and ginseng led by forest farmers), agroforestry policy, log inoculation and maple tapping, forest botanical plant husbandry (i.e. harvesting, subdiving, and replanting roots; storing and stratifying seeds), marketing forest botanicals, . We also gave a tour of our active forest farming propagation research beds at Smokey House, and in the evening had a bluegrass band provide live entertainment. We ended the conference with a visioning session, where we asked participants to brainstorm on the future of forest farming in the Northeast; we plan to use this feedback and information to inform the future of the NFFC now that our initial funding through SARE is coming to a close. Couldn't have asked for a better finale for this highly successful round of funding.

Milestones

Farmers receive an invitation to join the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition. Through their membership, farmers explore a wide array of online resources, and learn about opportunities for virtual and in-person networking and educational experiences and assistance in marketing new agricultural products. Farmers begin engaging with the online content/community, asking and answering questions, and learning about upcoming educational workshops in their region.

200

25

782

50

December 31, 2021

Completed

December 31, 2024

During Year 1 of the project we established 5 Research and Demonstration sites across the Northeast region. These plots, installed between September and December of 2021, will serve as the basis of our educational and research activities. More recently, we established a website for the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition that serves as the intake point for new and interested forest farmers in the region. The website was officially launched earlier in the month of December, and large-scale outreach efforts are planned for January and February of 2022. As of the writing of this report, the Coalition has been promoted to farmers at one major conference in the Northeast, the Forest Ecosystem Monitoring Cooperative Conference (a video of the talk is available here). We expect high levels of recruitment in the spring, coinciding with in-person educational events hosted at sites across the region.

Year 2:

Between membership sign up through the NFFC website and sign up at workshops, the Coalition has grown to 366 members as of January 4, 2023. We will continue to recruit new members through conferences, workshops, and online efforts.

Year 3:

As of the end of 2023, our membership has grown to 735, a huge success; we will continue to recruit new members.

Final Update:

As of December 2024 the membership of the NFFC is 782, for those who have signed up to be on the mailing list and engage with content regularly.

Three farmers assist in the establishment of research plots on their properties. Farmers provide input on the optimal location of plots, and participate in the collection of baseline environmental data. They receive training on species-specific maintenance and data collection protocol, including plant phenology, plant propagation techniques, data collection and data entry. This training prepares farmers to present on their project participation at project workshops in Project Year 3.

3

6

6

December 31, 2021

Completed

December 31, 2021

We worked with a number of forest farmers in the fall of 2021 to help install research plots. These forest farmers, who ranged in experience from new to veteran, received training in how to install the research plots, a different approach than planting only for production. In turn, these forest farmers provided input on where to locate plantings and the best time-frame to install plantings. We worked with 6 farmers and 6 agricultural service providers over the course of the fall, and installed plantings at 5 locations. In the spring and fall of 2022 we will return to these plantings to weed and collect preliminary data, and these farmers will join in this activity and learn about data collection protocol.

Year 2 update:

We completed our first round of data collection on all 5 R&D sites with the help of our farmer collaborators. We will be going back to all 5 sites in the summer/fall of 2023 to conduct our second round of data collection.

Year 3 update:

Sites were weeded and maintained in the summer of 2023, and we are actively planning a large data collection effort for 2024.

Final update:

Final data collection was done in summer/fall of 2024, see research section.

New and beginning forest farmers attend annual workshops (3 workshops each year with 25 attendees each over 3 years; 75 attendees per year, 225 over project lifetime). Farmers receive both field- (hands-on) and classroom-based educational opportunities, network with one another, meet regional technical service providers, and leave the workshop(s) with the fundamental knowledge required to start their own operation. Attendees are recruited into the coalition, and learn about project objectives, resources, and membership advantages.

225

15

758

140

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

We plan to hold our first in-person workshops in the spring of 2022.

Year 2 update:

Between the spring of 2022 and the fall of 2022 we held 4 in-person workshops with NFFC partners and spoke at one additional workshop.

Yale-Myers Forest (April 23rd, 2022)

Our first workshop took place at the Yale-Myers Forest and had 56 workshop attendees. The day included an introductory presentation on forest farming given by Karam Sheban, field-based discussions around forest botanical plant ecology and site selection lead by Professor Marlyse Duguid and Walker Cammack, and a forest botanical planting demonstration hosted at forest farmer Steve Prinn's property. Participants were given the opportunity to try planting ginseng, ramps, black cohosh, bloodroot, and goldenseal from both seed and root.

Sage Mountain Botanical Sanctuary (June 4th, 2022)

Our workshop at Sage Mountain fetched over 100 RSVPs but due to site restrictions and sensitive habitat we only had 20 people attend. The day started with an introductory presentation given by Walker Cammack and was followed by forest botanical plant walk focused on species identification that was lead by United Plant Savers affiliate Betzy Bancroft. Professor Marlyse Duguid also discussed forest botanical plant ecology with participants. A discussion around how Vermont land-use laws might affect the adoption and practice of forest farming was held by Sage Mountain director Emily Ruff during lunch. Finally, the day was wrapped up with a forest botanical planting demonstration in which participants learned and practiced best planting practices for black cohosh and goldenseal.

Wild Hudson Valley (September 10th, 2022)

This workshop was a collaboration with Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler of Wild Hudson Valley. 20 participants attended the workshop. Anna and Justin covered all-things ginseng ecology and cultivation. They provided samples of ginseng products, as well as recently harvested specimens to discuss identification and ecology. Anna and Justin then lead participants through their property while discussing ginseng habitat. The day ended with a hands-on demonstration of planting ginseng by seed. All participants were able to go home with their own 1/4lb bag of ginseng seed to be planted on their own property.

NRCS Training at Yale-Myers Forest (October 24th, 2022)

The NRCS Training was a collaboration between the NFFC and the CT, MA, and RI NRCS departments meant to train NRCS technical service providers in best forest farming practices. 30 NRCS agents from southern New England states attended. This was organized by the NRCS and individuals within the CT NRCS office. Lack of technical service providers with knowledge around forest farming has been identified as one of the biggest barriers to forest farming adoption, so we saw this as a wonderful opportunity to address this issue. The workshop started with a presentation by Walker Cammack on forest farming and the role of NRCS agents in supporting landowners interested in forest farming. The participants than went on a tour of the various forest farming sites at Yale-Myers Forest, including the NFFC R&D site. A discussion and exercise in forest botanical site selection was conducted at the R&D site before the day was finished off with a hands-on ginseng seed planting demonstration.

Speaking Events:

Upper Valley Agroforestry Transition Hub Tour (October 30th, 2022):

We gave and introduction to forest farming at the Dartmouth R&D site during an agroforestry tour that was a part of the curriculum for the Upper Valley Agroforestry Transition Hub's (SARE LNE22-441) farmer cohort.

Year 3 update:

This has been a big year for the NFFC. We hosted four in-person workshops and presented at three conferences, exceeding our goals for the year.

On February 18th, Walker gave a presentation on the NFFC work to a group at NOFA Vermont's 41st Annual winter conference in Burlington, VT, to a group of 70 farmers, forest managers, and technical service providers. Here is a link to the virtual presentation, which we've also posted on Resources tab of our website.

On March 27th we gave a presentation to mentors and mentees to inaugurate our mentorship program. We dramatically expanded the mentorship program from its original scope, to include 36 mentees and 11 mentors; so this presentation reached 47 people.

On September 2nd, our partner farm Wild Hudson Valley hosted an NFFC-funded "deep dive" workshop at their farm in the Catskills of New York for 27 attendees. This is the second year in a row Anna and Justin have presented with the NFFC.

On October 2nd Karam did a field presentation for a group of Yale master's students in a temperate agroforestry class at one of our replicated research plantings at the Yale-Myers Forest. There were 18 students present. This was an opportunity to check on research plantings, which revealed some exciting developments, including this seed plot where after two years of no growth, both planted ginseng seeds had germinated.

On October 10th, Karam and Walker hosted a forest farming cultivation workshop at Smokey House in Danby, Vermont, with 20 people in attendance. This event included an indoor presentation as well as a hands-on field component, where attendees planted ginseng and took home ginseng seed.

Between October 25th and 28th, Karam and Walker attended the National Society of American Foresters (SAF) conference in Sacremento, California, where they presented on three years of the NFFC to a packed conference room with 83 people in attendance. While not formally surveyed, this group contained forest landowners, university faculty and staff, professional foresters, and other technical service providers. Outside of the presentation itself, the event was a tremendous networking opportunity, and highlighted the cresting interest in agroforestry among the forestry community.

And finally, on December 7th, Karam presented virtually at the Savanna Institute's 2023 Perennial Farm Gathering on the NFFC work, as part of a group presentation on forest farming, alongside Robin Suggs of Appalachian Sustainable Development and Ingrid West of Misty Dawn Farm. This was the second highest attended session of the entire conference, behind the keynote (Robin Wall Kimmerer), so we felt pretty good about that! There were 161 people in attendance.

Project update after Year 4:

In 2024 we continued to have a diverse set of trainings and events serving farmers and service providers, despite having hit our metrics for . In April Karam presented on our research to a group of academics and practitioners at the Society of Ethnobiology in Missouri, with 26 people in attendance. In June, at the request of the National Agroforestry Center, project leaders Karam and Marlyse ran a workshop on forest farming for New England NRCS agents as part of a three-day training for Technical Service Providers on agroforestry practices relevant to the region. This all-day event included both classroom and field sessions.

And finally, in October of 2024 NFFC farmer mentors at Wild Hudson Valley hosted a ginseng wild simulated cultivation workshop for 20 beginning forest farmers, this is the third workshop they have hosted for us and they continue to be popular and overenrolled.

Our biggest event to date for this project was our final wrap-up conference. September 6-8 in Danby, Vermont, we organized and hosted the inaugural Northeast Forest Farming Conference at the Smokey House Center: https://www.smokeyhouse.org/event-details/2024-northeast-forest-farming-conference. We had 150 registered participants and a waiting list. Workshops largely took place in the field, with hands-on learning opportunities complemented by presentations given by expert speakers from the Northeast and from our experienced partners in Appalachia. Workshop topics ranged from species-specific cultivation (e.g. forest planting of ramps and ginseng led by forest farmers), agroforestry policy, log inoculation and maple tapping, forest botanical plant husbandry (i.e. harvesting, subdiving, and replanting roots; storing and stratifying seeds), marketing forest botanicals, . We also gave a tour of our active forest farming propagation research beds at Smokey House, and in the evening had a bluegrass band provide live entertainment. We ended the conference with a visioning session, where we asked participants to brainstorm on the future of forest farming in the Northeast; we plan to use this feedback and information to inform the future of the NFFC now that our initial funding through SARE is coming to a close. Couldn't have asked for a better finale for this highly successful round of funding.

Workshop attendees receive entrance and exit surveys at events, and engage through other data acquisition methodologies—parking lots, reaction cards, live-time phone polls, and listening posts—to track knowledge/skill acquisition and to provide feedback (3 workshops each year with 25 attendees each over 3 years; 75 attendees per year, 225 over project lifetime). Surveys allow participants to convey what knowledge/skills they have gained, as well as topics they require additional assistance on. Much of this data will be shared in live-time to make the data-acquisition process beneficial for both farmers and project researchers.

225

15

645

58

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

Surveys will be available to attendees at in-person workshops, to be held in the spring of 2022. An intake survey is available on our website, and can be viewed here: https://yalesurvey.ca1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3fxdwThNdx9KDrM

Year 2 update:

We have altered our approach to survey distribution after experimenting with distributing surveys digitally at our first workshop. We have found that distributing hard copies of intake and outtake surveys manually immediately before and after workshops leads to higher rates of response.

Year 3 update:

With updated survey methods, including in-person and digital, we've increased our response rate to well above our target numbers.

Final Update:

We continue to get good feedback from our polling and discussions with participants. During the Forest Farming Conference we included a listening session where we used recordings of break away sessions and generative AI to summarize notes and feedback from those recordings.

Farmers engage with educational resources provided in-person and online through the project. This includes connecting farmers to existing forest farming resources as well as to Northeast-specific resources created using project funds. We will track engagement through printed resources taken at workshops, unique downloads online, and views for videos. As a result, farmers have educational resources to reference when implementing project activities on their properties; and recruit new members when resources are shared within farmers’ networks.

250

10

4028

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

We have created a resources page on our website, available here: https://www.northeastforestfarmers.org/resources. These resources include a link to the Forest Farming YouTube channel, where we will eventually post videos created with project funds; a link to a virtual site selection tool to help beginning forest farmers determine where to plant forest crops on their own property; and a link to a free PDF of a book on cultivating the target understory species of this project, co-authored by PI Karam Sheban. We have not officially begun tracking the traffic to these resources generated through the website, but will have stats on that soon as recruitment to the site ramps up.

Year 2 update:

We are currently in the process of creating our own forest farming related resources including producer scenarios, a digital map resource that provides forest farmers with locations of nearby technical service providers, and a state-by-state summary of rules and regulations around forest farming. Once these resources are finished they will be added to the resources page of the NFFC website. In 2022, our current resources page had 364 unique visits.

Year 3 update:

As of the end of 2023, our website has over 4,000 view, with 843 views on the resources tab.

Final update:

Over the entire period of the grant the NFFC website has received over 6,496 visits; of which 4,900 were unique visitors. In 2024 we had 2,600 visits to the NFFC site, with 1,900 unique visitors, and over 4,322 page views. In 2024 486 farmers specifically engaged with the resources on the website. We continue to gain new members and continue to engage the network through our monthly newsletters.

In addition, we have six videos from workshops/conferences/webinars hosted on the Forest Farming Youtube channel, where they have over 1,000 total views.

Farmer members receive an invitation to provide feedback to project organizers, through an annual survey assessing effectiveness of project activities/resources and performance target metrics of adoption, as well as through a member survey link available online to continuously collect feedback. This will allow farmers to reflect on their experience with the project, and to participate in the development of the community. It will also allow project leaders to adjust activities/resources to best serve farmers.

225

10

485

17

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

This survey for forest farmers in forthcoming.

Year 2 update:

This survey will be sent out sometime in the winter of 2023.

Year 3 update:

Our network was surveyed in 2023 and provided the opportunity to share feedback and direct future programming. We intend to send out a final survey to help steer the project after our SARE funding comes to an end.

Final update:

We have 485 responses to our membership and feedback survey, we continue to collect responses and are in the process of collating and analyzing the data.

Interested farmers in the Northeast region are paired up with an experienced forest farmer mentor through a partnership with the Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition; project leaders vet interested Northeast farmers and Appalachian mentors and match farmers based on interests; samples questions/discussion topics are provided to facilitate a semi-structured consultation; mentors are compensated for up to three consultations.

10

47

11

December 31, 2023

Completed

December 31, 2024

Our mentorship program will begin in Year 2.

Year 2 update:

Our mentorship program will be launched in the winter of 2023 and will continue into the winter of 2024. The entire program will be virtual to be as inclusive as possible. Applications for mentees and mentors are being sent out in early January 2023 and we plan to have our cohorts of mentees and mentors set by February 2023. Mentees will then be paired with mentors and given the opportunity to set up 3 one-on-one consulting sessions in the winter/early spring of 2023. Mentees and mentors will then discuss with NFFC coordinators what topics should be covered in 2024 mentorship program curriculum. In 2024, mentees and mentors will have another opportunity to organize 3 one-on-one consulting sessions in addition to attending 5 online seminars that cover various topics that will help mentees launch their own forest farming enterprises. Both mentees and mentors will receive a $500 stipend for their participation at the end of the program.

Year 3 update:

We dramatically expanded the scope of our mentorship program, which launched in early 2023. The program includes 36 mentees working in small groups with 11 mentors. We set expectations for the number of meetings to be held annually and have regular check-ins with program mentors. We are planning a series of 3 virtual workshops exclusively for members of the program to take place between the late winter and spring of 2024.

Final update:

The mentorship program has been a tremendous success; despite formal support for the program coming to an end, about half our groups continue to meet with their mentors to ask questions and share insights and progress. This program also led to synergies, such as partnerships between mentees and mentors on additional projects and opportunities. NFFC project leaders also build on the relationships started in this program for additional programming.

Participating farmer-researchers co-present the results of three-year research trials at project workshops alongside key project individuals. Farmers develop presentation skills and science communication through communication of results and findings to their peers.

3

6

11

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

Presentations on results will happen after Project Year 3.

Final update:

Our farm-research partners presented at our summative conference hosted at Smokey House in September 2024.

Farmers will hear presentations from project PI and partnering farmer-researchers at major regional farming and forestry conferences. Presentations will be offered at conferences such as the New England Society of American Foresters (NESAF) Conference and the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA conference); these conferences will serve as a recruitment opportunity into the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition, as well as a chance to make important connections among farming and forest communities in the Northeast.

250

10

629

187

November 30, 2024

Completed

November 30, 2024

As of the writing of this report, the Coalition has been promoted to farmers at one major conference in the Northeast, the Forest Ecosystem Monitoring Cooperative Conference (see video below). The talk took place on December 17th, 2021.

https://streaming.uvm.edu/embed/41622/

Year 2 update:

In September of 2022 Coalition members presented initial research findings at the the Society of American Foresters National Conference. This event was also used as an opportunity to recruit members to the coalition.

Year 3 update:

To date, we have presented at 8 conferences for a total of 422 beneficiaries, exceeding our goals. We have plans to present at at least one additional conference in 2024.

Final update:

At project end, we presented at 11 conference for a total of 629 beneficiaries, far exceeding our goal.

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

We have designed an intake survey and have begun collecting data on new members of the NFFC. This survey was created in collaboration with Yale's Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. We will create similar surveys for in-person educational events to take place in the spring of 2022, and use these surveys to determine changes in knowledge, skills, and adoption.

Year 2 update:

We have been able to track knowledge/skills gained through exit surveys after our workshops. These estimated numbers do not include those who attended talks at conferences since we did not administer surveys to these attendees. This winter we will administer a survey to the entire NFFC membership network that will specifically ask members if they have had a change in knowledge, attitudes, skills or awareness around forest farming as a result of getting involved with the NFFC. This will help us better track this metric.

Year 3 update:

We have sent out numerous surveys tracking event attendee satisfaction and interest in future programming. We will conduct another round of surveying in 2024 to pull cumulative results together.

Final update:

Below are the average responses to post-event survey responses from 498 farmers, forest landowners, technical service providers, educators, and other attendees at educational events hosted through the Coalition over the past four years.

- Question: "Overall, how would you rate the workshop/event/conference?" Scale of 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor): average score: 1.38

The following questions asked participants to select an answer between 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

- "The presenters were effective in teaching the content at the workshop/event/conference" average score: 3.46

- "The workshop/event/conference increased my knowledge of forest farming best practices" average score: 3.38

- "The workshop/event/conference increased my confidence in my ability to adopt forest farming practices" average score 3.17

- "I plan to adopt one or more of the practices I learned at the workshop/event/conference" average score 3.00

- "I plan to attend another NFFC event in the future" average score 3.23

- "I plan to recommend these workshops/events/conferences to a colleague" average score 3.33

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

100

Farmers and forest landowners in the Northeast will integrate forest crops into the forested portion of their properties.

Create 50 forest crop acres in forestland across the Northeast; introduce 500 farmers and forestland owners to the practice of forest farming; and establish 100 new forest farming enterprises.

Generate $500,000 in profit potential across the 50 forest crop acres established by new forest farmers.

262

Began planting forest crops in their forestland in the Northeast.

66 crop acres of production established within 26,724 acres of forestland engaged by the NFFC.

$660,000 in profit potential across 66 acres established by new forest farmers in the Northeast region.