Final report for LNE22-441

Project Information

As a direct result of our work, agroforestry will be adopted by 25 farmers on a minimum of 25 acres resulting in the development of an agroforestry hub in the Upper Valley of Vermont and New Hampshire, a four county region. The hub will act as a source of resources for catalyzing further agroforestry uptake. Farmers will receive seedlings and support to bolster on-farm climate resilience measured programmatically by soil health indicators. Our target is 200 farmers reached through peer-peer networking and measurable improvements in soil water infiltration for 75% of the 25 farms participating in the training program.

Agroforestry deliberately integrates trees and/or shrubs with crops and/or livestock (e.g., alley cropping, silvopasture, forest farming, windbreaks, riparian buffers) to enhance ecological function and diversify production (Bentrup et al., 2018). Many agroforestry practices draw on Indigenous land management strategies, regionally and globally, providing critical grounding for contemporary efforts to reintegrate woody perennials into working landscapes and to reconsider how trees can support productive, resilient, diversified farm systems.

Agroforestry was widely cited for its potential to contribute to climate mitigation through carbon sequestration while also delivering benefits directly relevant to farm viability. Across Northeastern farm contexts, trees and shrubs were frequently framed as tools for buffering wind and flood impacts, moderating microclimates, conserving soil and water, providing shade and shelter for livestock, and diversifying farm products. These considerations were particularly salient in the Northeastern United States, where temperatures rose and extreme precipitation became more frequent (NCA 2014). Farmers across the region reported adapting to these shifts; for example, a survey of 193 farmers found that 72% had made changes on their farms in response to extreme weather (White, 2019). At the same time, climate change intensified production pressures, including reduced soil stability, livestock heat stress, drought risk, and increased pest and weed pressure (Howden et al., 2007; McCarl, 2010; Claggett, 2017).

Despite growing interest in tree-based climate solutions, the adoption of agroforestry remained slow. Limited access to locally relevant implementation guidance and sustained technical support remained a major barrier (e.g., Coggeshall, 2011; Fin et al., 2008; Gold et al., 2004; Jacobson & Kar, 2013; MacFarland, 2018). In addition, reliable access to appropriate trees and shrubs constrained implementation, particularly as broader reforestation and afforestation initiatives intensified demand within an already strained nursery pipeline (Fargione et al., 2021). The project was grounded in the idea that durable change required both horizontal knowledge exchange and vertical support across institutions (Rosset & Martinez-Torres, 2012; Rosset & Altieri, 2017; Carlisle et al., 2019).

The project addressed gaps in locally relevant guidance and sustained technical support. We integrated farmer-led education with research to close practical knowledge gaps and better align agroforestry strategies with farmers' goals and ecological realities. We created cohort-based, farmer-centered programming through an Agroforestry Transition Hub that served as a nursery, demonstration and learning site, and as a coordinating platform for training and network-building. Through this approach, we supported 25 farmers who were newly adopting or expanding agroforestry and prioritized resource-limited producers as primary program participants.

In parallel, we conducted research to clarify how adoption decisions formed and changed through learning, and how farm conditions shaped feasibility. We tracked engagement and decision-making among participants and partnered with 30 farms across sectors in the Upper Valley region of Vermont and New Hampshire to document perceived risks, barriers, and motivations related to trees and agroforestry. We complemented these social data with vegetation surveys and related ecological assessments to understand how management and global change dynamics shape treed systems on farms, yielding practical insights to strengthen establishment and stewardship under changing conditions.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Project 1: Exploring the tree planting and protecting culture of farmers in the Northeast: Opportunities for Agroforestry

Research questions

-

What types of trees are farmers actively protecting, planting, and preserving on their landscapes? Why?

Hypotheses: Farmers disproportionately retain trees with clear on-farm functions (shade/shelter, water/erosion control, boundary features) and culturally meaningful “legacy” trees; species choices reflect locally available, low-maintenance, and economically legible trees (e.g., maple, timber, fruit/nut) more than biodiversity goals alone. -

Do farmers want to plant more trees? How does this vary by sector?

Hypotheses: Most farmers express interest in planting more trees, but stated willingness is constrained by time, labor, and perceived risk; interest is highest in pasture-based/livestock systems and lowest where annual-crop mechanization and infrastructure lock-in increase opportunity costs.

Project 2: Investigating the prevalence of wooded areas and integrated trees on the agroecological matrix of New England farms

Research questions

-

What is the extent, structure, composition, and patterns of trees and herbaceous vegetation farms integrated into crop production, in marginal areas, and in woody patches?

Hypotheses: Trees are concentrated in edges, riparian zones, and “marginal” areas rather than evenly integrated into production fields; linear features (hedgerows/riparian strips) skew younger/denser and more early-successional than interior woodlots. -

How does this vary by agricultural sector, production style, land-use history, and demographic profile?

Hypotheses: Tree integration is higher on pasture-based/diversified farms and where land-use history includes reforestation; tenure insecurity and intensification are associated with fewer planted/in-field woody features and more fragmented woody cover.

The promotion of agroforestry was generally characterized by approaches that emphasized a few priority tree species within a restricted set of technological packages, without integrating farmers' perceptions of trees or considering larger-scale agroecological processes. As a result, new methods were needed to generate more diverse agroforestry options that could reconcile production and conservation objectives and better accommodate varying local conditions across broad scaling domains.

Through this initiative, we established two complementary research projects to address these concerns: investigating the extent and perceptions of trees in agricultural landscapes and examining scalable pathways for farmers to establish trees suited to agroforestry systems. Together, these projects created a robust profile of northeastern farm tree resources and generated practical information to support the successful scaling of tree planting to enhance landscape-level resilience.

Project 1: The tree planting and protecting culture of farmers in the Northeast: Opportunities for agroforestry

We documented the tree species that farmers utilized, planted, and protected on their land (as well as the species they hoped to add) and the motivations behind these practices. We highlighted multi-use species and examined how trees fit into land-use strategies and farm livelihoods. These findings informed recommendations for scaling agroforestry by building on farmers’ existing knowledge of trees, interests, and management practices rather than relying on narrow species lists or standardized packages.

Population: We interviewed 30 farmers across the Northeast and stratified participants by sector, size, and production style. We prioritized representation across prominent industries in the region, including dairy, vegetable production, fruit production, and livestock, and used farm census benchmarks to guide size thresholds and sampling across categories.

Methodology: We conducted semi-structured interviews on farms, typically paired with field walks, to capture how farmers described and interacted with woody vegetation across their landscapes (e.g., field edges, riparian areas, scattered “wolf” trees, and wooded patches). During interviews and walks, we compiled a master list of local tree names and recorded the uses, values, and concerns farmers associated with each species.

Data collection and analysis: We audio-recorded interviews, transcribed responses, and coded data using an anonymized codebook. We grouped responses into thematic categories within and across sectors and summarized patterns using frequency tables and comparative statistics where appropriate (e.g., tests of differences across sectors or farm types).

Farmer input: Farmers repeatedly emphasized that phone- or office-based conversations did not reliably surface the full range of trees on their farms. Field walks helped farmers notice and discuss wooded areas they might otherwise overlook and enabled more specific, management-relevant conversations about ecological function, labor, and economic tradeoffs. This project therefore centered farmer knowledge and on-farm observation as core inputs for designing agroforestry strategies that fit regional realities.

Project 2: Investigating the prevalence of wooded areas and integrated trees on the agroecological matrix of New England farms

Changes in forest species diversity and composition, structural diversity (Willis and Whittaker 2002), and the abundance of nonnative species were common national concerns for forests within the United States. Farm landscapes in the Northeast typically contained myriad plant communities that met the Forest Service’s definition of a forest patch (one acre, 120 feet wide); however, these patches were seldom studied or valued for their contributions to landscape health and resilience. Developing agroecosystems that promote resilience, therefore, required treating agricultural landscapes as heterogeneous mosaics of habitat patches and recognizing areas that retain some balance of original ecosystem structure as important to agricultural productivity (Francis et al. 2003). In this project, we used vegetation surveys to examine the extent, composition, health, and spatial distribution of trees on farms and to model how these patches contributed to climate resilience.

Treatments

We sampled 30 farms engaged through Project 1. On each farm, we identified and sampled up to six wooded patches (most farms had no more than six). We prioritized forested areas that met the Forest Service definition of a forest patch (≥1 acre and ≥120 ft wide), and we also included smaller wooded edges when farmers identified them as management-relevant (e.g., regeneration concerns, invasives, wet areas).

Methods

Patch selection and layout: Using farmer interviews and farm walk-throughs, we identified wooded features to sample and recorded basic patch descriptors (dominant overstory type, evidence of management/disturbance, adjacent land use, and edge condition). For each selected patch, we established two edge entry points to standardize sampling across farms.

Transects and woody vegetation: From each entry point, we laid a 60 m transect running from the forest edge toward the patch interior. Along each transect, within 2 m of the centerline (4 m total belt width), we identified all trees, shrubs, saplings, and vines. For any woody stem with a diameter>1 cm at breast height (DBH), we recorded its diameter.

Groundstory quadrats: To characterize the groundstory community, beginning at 5 m from the edge and then at 10 m intervals along the transect, we placed a 0.5 m × 0.5 m quadrat and identified and recorded all species in the groundstory layer, including herbaceous plants and woody seedlings/sprouts.

Soil sampling: At the center of each ground-story quadrat, we collected a soil core to a depth of ~25 cm using a standard steel soil probe to represent the rooting zone. Samples were individually bagged and labeled by quadrat, transect, patch, and farm, then stored frozen for subsequent processing.

Data Collection and Analysis

Vegetation: We summarized patch- and farm-level vegetation patterns using species richness and diversity metrics (e.g., Simpson’s index) and evaluated differences among patches and across farms using community analyses (e.g., ANOSIM) and comparative statistics as appropriate.

Farmer Input

Farmers consistently noted uncertainty about the economic, ecological, and social benefits of retaining or investing in wooded patches versus expanding field production. We used farmer-identified priorities to guide patch selection and to ensure that the resulting findings translated into management-relevant insights about the roles wooded areas play on farms and where targeted interventions (e.g., supporting regeneration, managing edges, controlling invasives) could strengthen climate resilience.

We also worked with farmers to interpret farm-specific results and address their questions about wooded patches and management options. In follow-up conversations, farmers provided feedback on which findings were most actionable, and these questions helped shape ongoing analyses and synthesis intended for broader dissemination (including potential co-authored outputs where farmers expressed interest).

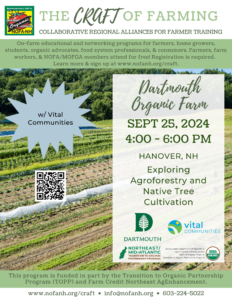

Outreach flyer: We used this flyer to reach a wide variety of farmers via email, phone, and at local events. In doing so, we were able to attract a breadth of farmers. We plan to do more outreach this winter to speak with farmers at their convenience.

Example Farm: The link shows examples of data farmers received from their farms.

Example farm: This link shows an example of the data sheets farmers were sent.

Project 1

Trees were pervasive elements of the working-farm landscapes we studied—present in woodlots, hedgerows, riparian buffers, windbreaks, and around barns, lanes, and other infrastructure. Farmers described actively managing these existing trees for multiple functions, including utility (shade/shelter, drainage and erosion control, boundary definition), aesthetics, timber/woodlot goals, and occasional income diversification. Across interviews, farmers consistently articulated potential benefits of adding trees for farm viability and climate resilience. However, new tree planting remained limited relative to the level of stated interest. This pattern held across farm types and management approaches, suggesting that low planting rates were not explained by biophysical constraints alone.

Farmers’ assessments of whether tree planting felt feasible clustered around differences in farm history and position. Multigenerational farmers commonly evaluated tree planting through instincts of risk, shaped by repeated cycles of economic and climatic volatility, prior program experiences, and hard-won operational efficiencies. In practice, this group favored changes that had clear returns, low added management burden, and a demonstrated fit with their system. Newer farmers, by contrast, often described simultaneously building financial stability and social legitimacy; they were attentive to how tree practices—and the language used to describe them—might bolster or undermine credibility with peers, landowners, lenders, and support providers.

Across farmer groups, enabling conditions converged around four linked themes: (1) Farmers emphasized that support was most usable when it was responsive to on-farm timelines, grounded in local conditions, and delivered through sustained relationships rather than one-off site visits. (2) Farmers frequently described the early years of tree planting as a period of concentrated costs (materials, protection, time) before benefits accrued, making the practice feel difficult to justify within tight margins. (3) Farmers described labor bottlenecks—especially during busy seasons—as a primary constraint. They were concerned that they lacked the skills for tasks like watering, protecting, pruning, and replanting after losses, nor would they want to prioritize them during a busy season. (4) Farmers reported that when support programs or technical providers approached tree planting with fixed sociotechnical ideals (e.g., the “right” practice, scale, or metrics), they often encountered misfit: long waits, bureaucratic friction, or rigid requirements that reduced trust and dampened participation.

Discussion

Across working farms, interest in tree planting was most consistently driven by immediate operational pressures—heat and extreme weather, wind and infrastructure damage, water management and erosion, livestock comfort, and the need to stabilize production amid increasing variability (Lane et al., 2019). Farmers discussed trees less as an abstract environmental intervention than as working infrastructure, evaluated through the same daily calculus as any other investment: risk, labor, and cash flow. This orientation helped explain why enthusiasm coexisted with low adoption. Farmers were not disputing that trees can help; they were weighing whether a practice with front-loaded costs and management demands could compete with projects that protect near-term viability. In line with other scholarship, tree planting was constrained by early expenses and labor, delayed and uncertain returns, and the difficulty of monetizing many benefits (Feder and Umali, 1993; Kassie et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2018; Waldman et al., 2020).

These barriers were intensified by land tenure and time horizons: leasing, short agreements, and uncertain succession shortened planning horizons and elevated the risk of long-duration investments, making trees harder to justify when farmers could not count on controlling land long enough to realize benefits (Mutabazi et al., 2015; Piya et al., 2013; Teklewold et al., 2019; Brooks, 2022; Murken and Gornott, 2022). In some cases, trees were framed as competing with the need to secure or expand annual productive acreage—an equity issue insofar as constraints tied to land access are unevenly distributed and can be obscured by “voluntary adoption” narratives. Farm histories further shaped what counted as feasible and credible. Multigenerational farmers often drew on inherited heuristics and lessons from past volatility and programs, favoring low-burden changes with proven returns, while newer farmers described legitimacy-building as part of farm work itself, making them especially attentive to how trees—and the language around them—might signal stewardship and innovation or invite scrutiny if framed as impractical. Importantly, many constraints were produced at the farm–program interface: when support systems embedded narrow ideals of the “right” practice—fixed scales, standardized metrics, rigid timelines—farmers described misfit, waiting, and bureaucracy that eroded trust and reduced participation, whereas relationship-based technical assistance that was timely, local, and iterative reduced uncertainty and allowed tree practices to be adapted to on-farm realities.

When new planting felt infeasible—especially for livestock farmers facing immediate needs for shade and shelter—farmers reported leaning more heavily on existing wooded areas. This reliance sometimes came at the expense of patch condition, suggesting that adoption constraints could redirect pressure onto existing tree resources rather than remove it. This dynamic reframed the adoption problem so scaling agroforestry was not only about adding trees, but also about recognizing, protecting, and stewarding the woody resources farms already had.

A working-lands lens, therefore, underscored that many farms already held substantial woody resources—woodlots, riparian strips, hedgerows, and regenerating edges—that contributed to resilience but were often rendered invisible in incentive structures that privileged new planting. In some cases, establishing “new” tree systems may involve clearing or simplifying existing woody patches to meet program templates, risking ecological loss and social backlash (Cook-Patton et al., 2021; Ollinaho and Kroger, 2020). These tensions pointed to a basic gap in how tree-based interventions were framed: before we could meaningfully evaluate what additional planting could (or should) accomplish, we needed to understand the condition, composition, and functional role of the woody communities farms already had. This premise motivated our second project, which shifted the focus from whether farms could add trees to what those existing woodlots and tree patches actually looked like—their structure and regeneration, species composition (including nonnative presence), signs of stress or degradation, and how their location within the farm mosaic shaped both management pressures and resilience potential

Project 2

Results and Discussion

We found that forest patches were a common feature regardless of production system: farms in diversified, livestock, and vegetable operations had broadly similar “portfolios” of patch types (e.g., continuous woods, hedgerows, riparian strips; Fig. 1; χ² = 12.114, df = 10, p = 0.2775). This convergence was consistent with the broader history of the region, where secondary forests are recovering across a landscape shaped by repeated clearing, intensive use, and reforestation, often yielding a recognizable “second-growth template” across many ownerships and land uses (Foster, 2004). In that sense, it was not surprising that production type alone was a weak predictor of understory composition: we saw only modest separation by production type (Fig. 2; ANOSIM R = 0.072, p = 0.0355), suggesting that shared regional legacies and recurring management pressures could drive a degree of ecological homogenization across farm forests, even as farms differed in their enterprises.

Where farms diverged more clearly was not in whether patches existed, but in what those patches contained and how they were organized at the patch scale. When we grouped communities by patch type, separation was clearer and the effect size larger (Fig. 3; ANOSIM R = 0.2255, p = 0.0011), indicating that “what kind of patch is this?” (riparian vs. hedgerow vs. continuous woods vs. swamp, etc.) mattered more than “what kind of farm is this?” Practically, this suggested that while farm forests could share a common second-growth baseline—shaped by similar histories and, in many cases, ongoing intensive edge maintenance or disturbance—the ecological differences that mattered most for management were organized by patch context and microenvironment. For adoption and implementation, the implication was straightforward: farms already contained distinct ecological zones, and protecting, managing, or restoring wooded areas was likely to be most effective when tailored to patch type and condition, rather than applied as a uniform wooded-area prescription.

The structural results reinforced that patch-specificity. The proportional mix of vegetation structure classes differed strongly across both production and patch types (Fig. 4; χ² = 64.104, df = 16, p = 1.05e–07), indicating that patches varied not just in species lists but in vegetation architecture—an important lever for habitat, regeneration potential, and resilience. Structural diversity was positively associated with total understory abundance (Fig. 4; df = 49, p = 6.49e–07), even though it did not necessarily translate into higher understory diversity. Finally, patch size showed a pattern that benefited from being interpreted through the lens of scale and heterogeneity rather than as a bumper-sticker conclusion: larger patches were associated with lower understory richness in our plots (Fig. 4; df = 45, p = 3.13e–05). Classic species–area logic often predicts more species with more area at the patch or landscape scale, but plot-level richness can be higher in smaller, edge-dominated patches because edges increase light and microhabitat variation (and thus local richness) while also increasing exposure to disturbance and invasion risk. Work explicitly disentangling edge vs. interior species–area patterns supports this scale-dependent interpretation, in which edge processes can inflate local richness even as interior dynamics differ.

Taken together, these two projects pointed to the same design problem from different angles: working lands were heterogeneous mosaics, and both ecological dynamics and support systems failed when they assumed uniformity. Lesk and colleagues made this point in a different context—showing how “uniform” perturbations can miss the temporal complexity and spatial heterogeneity that shape on-the-ground outcomes —which offered a useful parallel for why one-size-fits-all tree programs often misfit farm realities. The combined implication was a broader “protect/manage/restore” approach (Cook-Patton et al., 2021) that treated existing woody patches as valued infrastructure (and managed them with patch-type specificity), while strategically supporting new establishment where it added function without displacing existing benefits or forcing farms to contort themselves to program templates.

Conclusions and recommendations for adoption on working farms

Across both projects, a clear conclusion emerged: tree planting and agroforestry were rarely constrained by ecological feasibility alone. Instead, adoption hinged on whether trees fit within the social and economic realities of farm management—especially time horizons, labor capacity, legitimacy pressures, and the credibility of support systems. Farmers did not describe trees as an abstract environmental good; they evaluated trees as working infrastructure, and their willingness to adopt depended on whether tree strategies could compete with other investments that protected near-term viability. This pattern helped explain the persistent gap between high stated interest and relatively low rates of new planting: establishment years concentrated costs and labor, while benefits were delayed and uncertain, and these risks were amplified when land tenure was insecure or when farmers lacked the administrative bandwidth to navigate programs.

Project 2 clarified why “fit” also had to be ecological, not just social. Most farms—regardless of production system—already contained similar portfolios of wooded patch types (continuous woods, hedgerows, riparian strips, wet patches), meaning that opportunities to gain benefits from trees were broadly distributed across farm types rather than limited to already “tree-forward” operations. At the same time, the ecological differences most relevant to management were organized by patch type and structure, rather than by enterprise category. Understory composition diverged modestly by production type, consistent with a shared second-growth baseline and some homogenization driven by regional legacies and recurring management pressures (Foster, 2004), but community separation was clearer by patch type and vegetation architecture. This indicated that effective stewardship—and therefore farmer confidence in results—depended on treating farms as heterogeneous mosaics and tailoring actions to the specific patch context. Taken together, the results suggested that tree initiatives would scale most equitably when they (1) aligned program design with farmer-defined viability and legitimacy needs, and (2) operationalized ecological heterogeneity by supporting patch-type–specific strategies that began with the resources farms already had.

Program and technical-assistance recommendations to increase adoption

Tree-planting and agroforestry initiatives are more likely to reach a wider range of farms when they are designed around farmer-defined goals (risk reduction, operational feasibility, credibility) rather than one-size-fits-all technical templates. Three changes are especially consequential.

First, technical assistance should be timely, locally relevant, and relationship-based. Farmers described support as most usable when it arrived on farm timelines, included site visits, and was paired with sustained follow-up. Peer-based learning and demonstration farms can increase credibility and reduce perceived risk, but they are most effective when paired with expert support that helps farmers translate ideas into designs that fit their specific constraints.

Second, financial support should be multi-year and tenure-aware, explicitly addressing the establishment period during which costs are high and benefits are delayed. Farmers were more likely to consider planting when financing matched the time horizon of tree establishment, reduced upfront costs, and allowed reasonable livelihood benefits from tree products, or avoided penalizing farmers for slow returns. Where tenure is insecure, adoption will remain structurally constrained unless programs can accommodate leasing realities (e.g., portable or staged investments, contracts that align incentives across landowners and operators).

Third, labor should be treated as core infrastructure rather than a private burden. Establishment and early maintenance are labor-intensive, and many farmers described labor bottlenecks as the decisive constraint. Programs that support workforce development/retention, cost-share labor, or promote low-burden designs and staged implementation can shift tree planting from “good idea” to feasible practice. Importantly, these changes also function as equity interventions: they reduce the likelihood that adoption pathways disproportionately serve only the most resourced or institutionally legible operations.

Management recommendations for farmers: practical strategies that fit heterogeneity

The ecological results pointed to a parallel conclusion for on-farm decision-making: farms already contained a mosaic of wooded patches, and benefits could often be expanded by starting with protect/manage actions before (or alongside) new planting. For many farms, tree benefits do not require a full transition to agroforestry; they can begin with stewardship that improves the health and function of existing hedgerows, riparian buffers, small woods, and wet patches while longer-term planting plans develop.

Management was also most effective when organized by patch type rather than farm type. Because patch context was a stronger predictor of understory composition and structure than enterprise category, a riparian strip will respond differently than a hedgerow or a continuous woodlot regardless of whether the surrounding farm is livestock-, vegetable-, or diversified-oriented. This patch-type orientation offers a concrete way to operationalize heterogeneity: it allows farmers and technical providers to match interventions to the specific constraints and opportunities of each patch, improving the odds of visible success and sustained engagement.

Within patches, vegetation structure is a controllable lever that can improve recruitment and function. Where feasible, maintaining multiple vegetation layers, protecting regeneration pockets, avoiding blanket edge mowing, and reducing chronic browsing pressure can increase understory abundance and support tree recruitment. At the same time, the patch-size result cautions against using “diversity” as a headline success metric. Smaller, edge-heavy patches may appear species-rich because edges increase light and microhabitat mixing (a scale-dependent pattern consistent with species–area and edge effects), but that richness can coincide with higher disturbance exposure and invasion risk. For adoption, the practical message is to pair edge-focused strategies (often important for buffers and hedgerows) with monitoring and targeted invasive management, and to value large, closed-canopy patches for stability and long-term regeneration even if plot-level richness is lower.

Finally, farms should aim for a patch portfolio rather than expecting any single treed area to deliver every benefit. Maintaining a mosaic—buffering riparian and wet areas, keeping hedgerows for connectivity and wind protection, and stewarding continuous woods for long-term stability—spreads risk, diversifies functions, and allows incremental progress that fits farm schedules and constraints. This portfolio framing also aligns with the broader “protect/manage/restore” approach: protecting and improving what already exists can generate near-term gains and reduce pressure on degraded patches, while creating conditions that make new establishment more feasible over time.

Education

Engagement

To recruit farmers for the programming offered through our project, we relied on our stakeholders' networks to support outreach. We advertised the project through relevant listservs, local newspapers, local events, and our social media channels.

Over the grant period, we delivered three cohorts of educational programming supporting 25 farmers total:

-

Cohort 1 (Fall 2022): an eight-session course (condensed from the original ten-session plan) with hybrid participation options and field-based components when feasible.

-

Cohort 2 (dairy-focused; 2024): a cohort of 10 dairy farmers, implemented in partnership with the White River Conservation District over several months with multiple farm visits and five field days/workshops to support relationship-building and individualized grazing + agroforestry planning.

-

Cohort 3 (resource-limited farmer short course; 2025): a three-day intensive short course for 10 resource-limited farmers across New England and New York, preceded by site visits and supported by shared lodging to maximize peer learning and cohort cohesion.

Across cohorts, farmers worked through shared goals, roadblocks, and solutions for advancing agroforestry projects with industry experts and one another. Participants developed portfolios and implementation plans, tracked short- and intermediate-term benefits and tradeoffs, and received written feedback from the project team.

To stay connected with farmers and elevate the importance of continued education and networking to the success of agroforestry initiatives in the Northeast, participating farms served as learning sites and peer anchors within the broader project network, including through field days, workshops, and follow-up conversations that connected new and prospective practitioners to on-farm examples and practical resources.

We collaborated with the DALI Lab, a partnership between Dartmouth undergraduates designing web applications and faculty seeking support to make research accessible, to design a website to reach practitioners and others interested in enhancing agroforestry within their communities. The website was used to share farmer portfolios and project resources, track progress on project objectives, map a network of members engaged in the program, and share events.

Learning

Based on farmer correspondence, extensive literature review, and assessment of similar programs, we designed a workshop sequence that covered a consistent set of core topics across cohorts, while adapting emphasis, pacing, and delivery format to cohort goals (e.g., dairy grazing integration, resource-limited farmer accessibility, or broader introductory training). The topics below reflect the core themes covered across cohorts, with cohort-specific aims integrated into each:

-

Agroforestry foundations: the five USDA agroforestry practices and the role of trees on working lands

-

Ecological functions and climate resilience: microclimate, water, soils, and risk buffering in farm systems

-

Site assessment and planning: translating farm goals into feasible designs; working through constraints and opportunities

-

Species selection: matching species to site conditions, practice type, and farmer priorities

-

Propagation and plant material: sourcing, stock types, and practical constraints in getting the right trees

-

Establishment and protection: planting strategies, protection, and early-stage survival bottlenecks

-

Maintenance and care: pruning, grazing interactions, watering, and long-term stewardship

-

Troubleshooting and monitoring: adaptive management and tracking outcomes that mattered to farmers

-

Markets and funding: regional market opportunities and longer-term funding mechanisms

-

Pilot farm leadership and peer learning: supporting farmer-to-farmer exchange, demonstration, and ongoing network-building

Across cohorts, we conducted individual site visits with participating farms to discuss goals and spatial and temporal elements relevant to implementation. During visits, we used a drone to capture aerial imagery of farm landscapes and used those materials to support site planning (e.g., identifying spatial constraints and opportunities relevant to establishment and stewardship).

We met at field demonstration sites, including the Dartmouth Organic Farm and other suitable locations in the Upper Valley/Northeast, to ground lessons and maximize educational opportunity. We supported remote access where needed and filmed sessions to create additional resources for people unable to attend in person.

When suitable to outplant, farmers received seedlings to begin their projects. As part of each operation’s implementation plan, researchers at Dartmouth worked with farmers to develop monitoring plans that tracked desired benefits of agroforestry systems (e.g., soil aggregate stability and water infiltration in a riparian buffer; net present value of a forest farming system). Farmers provided updates after each growing season, which we tracked and shared through program materials and the project website.

Evaluation

Over the course of three years, we monitored our program to ensure that we met goals and expanded our reach. Metrics were discussed in monthly and annual meetings by program partners.

Programmatic success was tracked by:

Number of partners engaged (tracked annually by Ong Lab)

Year 1: Partners engaged through one-on-one meetings and group meetings: 76 (see spreadsheet: Connections)

Year 2: Partners engaged through one-on-one and group meetings: 94 (see tab: Connections)

Number of trees donated to farmers (tracked annually by Ong Lab)

Year 1: 0. However, we had orders in for 100+ trees and ~1000 trees growing.

Year 2: We donated 700 high-value trees to farmers.

Year 3: We donated 2134 high values trees to farmers. We distributed remaining trees in Spring, and additional trees were donated to the White River Natural Resource Conservation District to distribute to more farms.

Number of trees planted (reported annually by farmers)

Year 1: 0.

Year 2: 750 trees.

Year 3: 3120 trees. We assisted four different farms from our first cohort with planting projects (constituting 285 trees).

Number of acres planted with trees (reported annually by farmers)

Year 1: 0.

Year 3: Farmers planted trees across 35 acres collectively.

Success of trees (reported annually by farmers)

Year 1: N/A

Year 2: We were still collecting data with our first cohort to assess first year growth.

Year 3: We reported a 95% success rate of plantings.

Pre and Post training evaluations (see Milestones for information)

Update 2023: We conducted our first cohort between October 20, 2022 and December 2, 2022. We condensed the class into eight sessions as opposed to ten and allowed for hybrid participation for non-field site visits for ease of farmers and to ensure that skill-based courses could take place in the field despite weather restrictions (see "flyer" for information on site, date, and speakers for our sessions). In our programming, we balanced vertical and horizontal knowledge sharing by bringing in a suite of locally active agroforestry speakers (11 in total), with conversations before and after classes among participants, and by providing additional resources for farmers to share their thought processes. This culminated in site visits, which generally occurred during the last two weeks of the course at the properties of the various farmers we were working with, so farmers could share their ideas, questions, and lessons learned from the class with us. This effectively allowed farmers to engage in knowledge sharing, building a skill set that served the broader agricultural community, as they acted as agroforestry lighthouses in subsequent parts of the project. We could not conduct a site visit at one farm (2 farmers working there) because of COVID-19 exposures/infections they experienced over the last four weeks of the course. We hoped to follow up with them in the spring. Darnell Martin filmed each course, so we had additional resources to share when the videos were edited to others interested in the course's information but not local to the region as well as those unable to participate. Trees on Farm Project : Flyer for the first course we conducted.

Update 2024: We conducted our second cohort by pairing up with the White River Conservation District to assist dairy farmers in establishing comprehensive and complementary grazing and agroforestry plans. This course occurred over several months to coordinate farms effectively. Due to logistical factors and lessons learned from the previous cohort, we combined our two planned cohorts of five farmers into one cohort of ten farmers to allow for more relationship-building between various managers, and to spend more time getting to know each of the farmers and catering plans to their specific needs over the course of several site visits. We spent more time working individually with farmers and intentionally planned field visits (see flyers below) between site visits. This allowed us to cover topics comprehensively and bring lessons learned back to each individual farm. We conducted five total field days/workshops and coordinated twelve different speakers to bring into the field. Between our two cohorts, we helped write seven different grant proposals for the American Farmland Trust and Northeast SARE. Field Day 1 Cohort 2, Field Day 2 Cohort 2 , Field Day 3 Cohort 2, Field Day 4 Cohort 2

Update 2025: We finished up our dairy focused cohort with two additional field days Field Day. We co-hosted a workshop on tree cultivation with Vital Communities. Additionally, we hosted a three-day workshop for our third cohort of 10 resource-limited farmers across New England and New York. For each of these farmers, we conducted preliminary site visits prior to the three-day workshop. Farmers stayed in lodgings together to maximize time and continue bonding. For this cohort, we completed site visits prior to the educational programming, provided a number of materials (e.g., aerial photography, funding opportunities, brief blurbs), provided printed materials (e.g., tree inventory, zines, funding pamphlets), and used an online website with an online curriculum that farmers completed prior to the weekend. The program had strong auditor attendance and high engagement and satisfaction among participating farmers. Agroforestry Short Course Flyer , Short Course Schedule

Milestones

To give a brief overview of the work we completed, we are excited to share a video Benedict Digiovanni created to summarize our work. Additionally, we have another video update for the most recent cohort (Cohort 3, 2025).

Milestone 1. Engagement: Convene agroforestry transition team

Description: Key to this project’s success were strategic regional partners that brought together agents of change in agroforestry transitions. We convened our first meeting of our project team and advisory committee in month one. Key members met monthly to review programmatic success, and advisory committee members joined as they saw fit and attended annual meetings.

Partners engaged: 15

Completion date: June 2022, followed by monthly meetings

Status: Complete

Milestone 2. Engagement: Develop curriculum for farmer training program

Description: In the first six months of our project, we developed curriculum for our farmer training program. We engaged stakeholders (including NRCS agents, farmers, foresters, agroforestry specialists, hydrologists, and wildlife biologists) to provide feedback on each workshop’s curriculum and connect more potential actors of change to our project. Curriculum was made publicly available via our website following development. (Updated 2024)Partners engaged: 25

Completion date: First round of outreach: August 2022; curriculum available by August 2023

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: We successfully engaged over 90 partners in the goal of our programming through one-on-one meetings, email exchanges, and participation in working groups and meetings. This datasheet (Updated 2024) holds different connections made in the project. Although we found that our curriculum needed to be reflexive from cohort to cohort, we developed an extensive number of resources and curated them for accessibility at the program’s completion. We developed a Wordpress site to make each session’s activities, videos, and prompts accessible following the completion of our third cohort: find it here: https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/agroforestrytransitionhub/.

Milestone 3. Engagement: Conduct structured stakeholder interviews

Description: We interviewed 30 farmers in the Northeast to inform our educational programming and infrastructure with more diverse and inclusive options for agroforestry implementation tailored to a local context. Through site visits and semi-structured interviews, we educated farmers about the function and composition of trees on their property, engaged farmers in our programming, and tapped into farmer networks for recruitment.

Partners engaged: 30

Completion date: October 2024

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: We conducted 15 interviews in year one, which helped us understand the current needs of farmers in the area and helped inform the nature and scheduling of our programming. In year two, we finished the second fifteen. The data and conclusions are available in the reserach section of this report.

Some favorite photos from two seasons of field work!

Milestone 4. Engagement: Establish nursery and agroforestry sites

Description: We established a nursery as a source of trees for agroforestry establishment in order to subsidize the cost of initial seed trees. We established trees from seeds or by cuttings sourced from climatically suitable species. We developed our own agroforestry site at the Dartmouth Organic Farm with fourteen woody species in a fractal to showcase diversity and maximize education and research opportunities.

Partners engaged: 25 farmers formally visited

Completion date: August 2022

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: Both the nursery and the experimental agroforestry sites were successes. We used these sites to engage farmers in different ideas as well as various external community members.

Dartmouth students helping with the nursery's inaugural plantings.

Nursery in Year 2.

Milestone 5. Engagement: Design and launch webpage

Description: We devoted significant time to developing a website with the DALI Lab. The platform served primarily as a curriculum and resource space to support practitioners, and included project metrics, farmer portfolios, events, and shared videos and written resources. We tracked engagement via pages viewed, materials downloaded, and inquiries received.

Farmers engaged: Approximately 550 farmers interacted with the platform

Completion date: Launch in September 2022; completed in 2024

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: You can find our website here!

Milestone 6. Learning: Conduct farmer training program

Description: Twenty-five farmers engaged in the training program on the science and practice of agroforestry. Farmers created portfolios on progress establishing agroforestry systems, received individual site visits, and participated in field workshops taught by key members and guest speakers. Throughout sessions, farmers networked and shared ideas for advancing agroforestry projects.

Partners engaged: 25 farmers

Completion date: Launched in November 2022; trainings occurred through 2025

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: We engaged 25 farmers fully in the curriculum we developed with partners around agroforestry. We ended up doing three cohorts instead of five, but engaged an equal number of farmers; this decision was made to more deeply engage with farmers. Our first cohort consisted of 6 farmers who participated in an 8-week hybrid (in-person/online) farmer training with eleven local guest speakers. We also made programming available to auditors (those not actively farming, unable to attend all workshops, or not prioritized in our application but interested in participating), which strengthened discussion and expanded networks. Our second cohort consisted of 10 dairy farmers. We conducted three field days and over twenty site visits. Field days were open to non-enrolled attendees, with over 50 participants in the first field day, 35 in the second (very rainy) field day, and 25 in the third field day. For our last cohort, we had 14 farmers participate and over 100 applicants. We prioritized resource-limited farmers and redesigned curriculum to support remote engagement and an intensive multi-day format.

Below are photos of our first cohort in the field and at the Dartmouth Organic Farm.

Photos below are our second cohort in the field during various learning engagements.

Photos below are our last cohort in the field.

Milestone 7. Learning/Evaluation: Monitoring socio-ecological outcomes

Description: We worked with 25 farmers to develop a monitoring plan that tracked desired benefits of agroforestry systems and answered process-level questions to reduce risk for other interested practitioners. Farmers provided updates annually on our online platform where feasible.

Partners engaged: 25 farmers

Completion date: Monitoring began in 2023 and continued annually through November 2025

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: With each farmer we worked with, primarily during site visits, we helped develop a research idea and a way to track progress. Research questions included the composition of birds visiting agroforestry plots, changes in weed composition with trees, and amount of understory establishment.

Milestone 8. Learning: Foster peer-to-peer learning and co-develop agroforestry lighthouses

Description: We supported farmers in acting as leaders in agroforestry by helping them share projects with their communities in ways that fit their capacity and context.

Partners engaged: 200 farmers

Completion date: Activities occurred annually through November 2025

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: In our first cohort, we helped participants develop outreach plans or integrate agroforestry projects into existing outreach and education initiatives. Three farmers incorporated agroforestry projects into public outreach events (e.g., a “Black Walnut Salon,” gatherings in a multistory food forest, and an art event centered around trees), with farmers self-reporting that over sixty people participated through these efforts. For our second cohort, we held gatherings with six farmers at their respective farms. Other farmers preferred engaging peers informally rather than through public-facing events. We connected members of the second cohort to participants from the first to foster cross-cohort relationships. We also planned a field tour showcasing agroforestry projects in Fall 2025 and continued developing the DALI Lab app to support virtual sharing of information and resources.

Milestone 9. Evaluation: Solicit and analyze feedback

Description: Farmer members received invitations to provide feedback to project organizers through annual surveys assessing effectiveness of activities and continued support. Participants in the Farmer Training Program also received surveys following participation to reflect on experience and support program development.

Partners engaged: 25 farmers

Completion date: Occurred annually through November 2025

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: Across all three cohorts, we gathered extensive feedback from participating farmers and auditors. Pre- and post-course surveys and session-specific feedback gauged changes in knowledge, perceptions, and enthusiasm for agroforestry practices. Participants reported substantial gains in knowledge and confidence. In Cohort 1, participants rated their understanding of agroforestry concepts as 1.4/5 before the course and 4.2/5 afterward. Across cohorts, participants described increased ability to envision practical applications and integrate agroforestry into farm planning and outreach. Quantitatively, all three cohorts saw significant improvements in ratings of agroforestry knowledge.

Milestone 10. Evaluation/Learning/Engagement: Share outcomes in conferences

Description: Farmers heard presentations from the project PI and key members at regional conferences and meetings (e.g., NOFA, Just Food, AFTA). These conferences served as recruitment opportunities and exposed more potential practitioners to agroforestry.

Proposed number of farmer beneficiaries: 250

Completion date: November 20, 2025

Status: Complete

Accomplishments: In summer 2022, we attended the World Agroforestry Conference to share project ideas and engage with other practitioners. We actively engaged in the VT Farm to Plate Agroforestry Working Group. We presented at the Temperate Agroforestry Conference (February 2024) and the Integrative Conservation Conference (February 2024). Several professionals we met at conferences later served as guest speakers or resources for local farmers. We presented at a variety of community meetings and presented at NOFA Conferences.

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

25

Incorporate woody species into farm

25 acres

soil water infiltration improvement

25

Incorporate woody species into farm

35 acres

Farmers planted trees across myriad landscapes to enhance the resilience of their landscapes. Farmers had high success (over 95%) of trees planted and all farmers reported positive benefits related to their tree planting.

Overall:

We have successfully completed programming with all 25 participating farmers and engaged over 100 additional auditors through our various programs. The diversity, complexity, and depth of the projects farmers are undertaking have been remarkable. Each farm brings unique challenges and goals, underscoring the need for tailored agroforestry practices rather than prescriptive solutions. This initiative has highlighted the resilience and innovation of farmers across the region.

Cohort 1:

The first cohort included six farmers who collectively planted over 300 trees as part of their agroforestry systems. While some trees were distributed directly to farmers, most were planted collaboratively with the farmers and our team. In addition to the participating farmers, the program attracted 30 auditors, including farmers, technical service providers, and educators, as tracked via event sign-up sheets. Participating farmers have shared their experiences with peers and community members, further amplifying the impact of the program.

Cohort 2:

The second cohort featured ten dairy farmers and included field days that attracted nearly 100 attendees, as recorded on sign-up sheets, along with over 35 site visits. We completed planting projects with all participating farmers, tailoring educational materials to each farm's specific needs. These materials included planting and monitoring plans. Additionally, we measured soil infiltration and conducted soil tests at each site to guide successful project implementation.

Cohort 3:

In the third cohort, we worked with ten farmers from across New England and New York. After conducting site visits and providing mentorship, we helped each farmer develop customized plans and supplied them with trees to implement their agroforestry projects independently. although we have been helping with implementation and more planning. This cohort demonstrated the regional interest in innovative and site-specific agroforestry practices.

Reflection:

This project has been a powerful illustration of farmer ingenuity and adaptability. Each participating farmer has approached agroforestry with a unique vision, addressing the specific challenges of their farm and landscape. The collective success of these programs has further emphasized the importance of fostering resilient and individualized agroforestry solutions in our region.

Additional Project Outcomes

As highlighted earlier, we successfully invited auditors to participate in the program, engaging over 150 additional individuals across both cohorts. This approach significantly broadened the reach of our programming, fostering connections between participating farmers and a diverse group of non-farmers interested in agroforestry in the region. The inclusion of auditors enriched the program by introducing fresh perspectives and expanding networking opportunities within the agroforestry community.

During the second cohort, the increased number of site visits provided a valuable opportunity to deepen collaborations. By inviting more experts to engage directly with farmers, we facilitated the development of actionable plans and explored innovative funding sources. This hands-on approach strengthened the ties between practitioners and experts, enhancing the program’s impact.

Additionally, we collaborated with the White River Conservation District on a grant initiative to provide educational programming for an upcoming grazing-focused cohort through the Northeast Dairy Business Innovation Center. While we did not receive direct funding from this effort, our contributions to the grant materials helped secure $150,000 for the project. This fruitful partnership has significantly advanced our regional planning efforts and highlighted the value of cross-organizational collaboration.

We also supported fifteen farmers, spanning both cohorts, in applying for further funding via American Farmland Trust, NRCS, Working Lands Grants, SARE Farmer Grants, NOFA grants, and more. These efforts continue to expand agroforestry adoption across the region while providing critical financial support to participating farmers,.

Although we felt inspired by all of our farmers, we particularly wanted to showcase a farmer who contributed greatly to our own understanding of future food systems in the region while making the most out of resources made available throughout the cohort. This participant is a farmer who owns a diversified production (vegetables, chickens, and value added products) in Northern Vermont. Her farm has served as a food and educational site, as well as a performance space for artists. When she first joined the Agroforestry Hub, she had a slight knowledge of agroforestry practices– though she understood some environmental benefits, she had limited knowledge of system design. As an initial idea for implementing agroforestry on her farm, she stated, “We have a hillside that was logged out… and we have been considering how to replant it, creating a food forest, orchard, or managing water & run off.” After a course on species selection, she used her learnings to expand her thinking, stating in a second workshop reflection: “I'd like to create a windbreak stand of edible species along the stream. Plums, Cherry Plums, Asian Pears, Crabapple, Roses for Rose hips, pie Cherries, Pawpaws and Hazelnuts all appeal to me… I'm thinking about how to do edible food hedgerows on all our boundaries, along the waterways, & around the ponds.” This participant also gained inspiration from her peers and guest speakers. After our field day to Perfect Circle Farm, managed by Buzz Ferver, she described that she became interested in “Putting in seedling starting beds in one field for growing out trees, shrubs and rare crops from seed like [expert from programming] does - Very inspiring site indeed!” It is notable to mention that at that site, they shared out a story of the importance of some seed that an expert we brought in from programming has from Salem Oak tree, and the significance of this particular tree marginalized communities. This resulted in a discussion about the many values of trees on farms, particularly the often neglected by mainstream agroforestry campaigns, cultural values.

The growth this participant experienced when it came to funding opportunities was also astounding. She detailed how she often had trouble applying for farm project funding, stating that she “never thought to apply for any of these funds or technical assistance due to fear, and to not understanding the specific jargon and lingo that is used.” She particularly mentioned legacies of land being stolen from their families, and intergenerational warnings of working with government entities. Yet, after taking the funding applications portion of our Agroforestry workshop, she felt empowered to reach out and seek help from our NRCS guest speakers in applying, putting in an application for several grants. This participant, along with many other participants, stated the importance of having technical service providers throughout the program. In reference to her grant applications, Ama now states, “I hope to be approved and offered a good contract that I can fulfill!”

As the workshop has come to an end, we have been inspired by her wish to connect others with agroforestry. We planted over fifty high value trees across her farm in various challenging areas. As she has stated in an exit survey, “It's invaluable to me for us to meet and connect with other farmers across the state of VT… May I serve as a mentor and educational spot for young farmers and agroforesters? I'm very dedicated to working with farmers in VT and the other NE states… Could we host design workshops here in collaboration? Cowrite grants with you and SARE?” Since, this participant has shared out her project with many farmers as well as community members through her popular salon style gatherings where she gathers a nexus of "foodies, farmers, and novices". She successfully has been funded by NRCS for a hoophouse on her site and we are working to apply to new funding sources to expand her agricultural and educational activities on her farm.