Final report for LNE22-443

Project Information

Problem and Justification

Gastrointestinal parasites affect virtually all grazing livestock. Traditionally, parasite management involved the single approach of administering dewormer to all animals on the farm multiple times per year. However, this practice has inadvertently resulted in the development of dewormer resistance, which represents a risk to livestock farmers in regards to animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and economic return. The economic loss associated with dewormer resistance is two-fold because it represents a direct cost to the farmer and limits the number of fully effective dewormers available in critical animal health situations. Dewormer resistance has been well-recognized in small ruminants, and the concern for the development of resistance in parasites relevant to other livestock, including cattle and horses, is growing. Therefore, it is necessary for livestock farmers to adopt new ways of controlling parasites in their animals.

Solution and Approach:

To mitigate the development of dewormer resistance and improve the economic return of dewormer administration, farmers must become more selective in their use of dewormers and utilize other management strategies, such as good pasture and animal management, to control the parasite load in their animals. To that end, the goal of this program was to highlight the components of a successful parasite management program and help farmers understand how these strategies can be applicable in their specific situation. The project team utilized a combination of one-on-one consultations and field day instruction events in order to help livestock farmers in Maryland learn how to: 1) employ good pasture management practices to control parasite load; 2) monitor parasite load to determine if and when dewormer application is necessary; 3) adopt one of several selective-deworming strategies; 4) utilize appropriate techniques for selecting and administering a dewormer; and 5) evaluate the performance of a dewormer on their farm. One-on-one consultations focused on building individualized parasite management programs for participants and teaching them to apply these strategies in their own unique situations. On-farm field days also focused on teaching these strategies and provided an opportunity for participants to ask questions and learn about the experiences of each field-day host farm in the context of parasite management. Post-participation surveys were conducted to document knowledge gain and behavior changes that occured as a result of this program. Two research studies were also carried out in order to document the effects of 1) improved pasture management on apparent parasite load of pregnant dairy heifers; and 2) forage type (annual vs. perennial) on parasite load of beef cattle and sheep. These studies provided data to further support the benefits of using pasture management to help control parasites in livestock.

We estimate that 30% of program participants (54 farms) will make at least 1 alteration to their parasite management program, which will affect approximately 1,080 animals and 2,500 acres. Utilizing these practices will reduce the amount of dewormer purchased and applied by each of these farms by 30%, resulting in an annual savings of $3/head/year.

Description of the Problem

Most livestock producers are aware that gastrointestinal parasites can reduce performance, and accordingly, take measures to protect their animals. Gastrointestinal parasites are typically controlled through application of dewormers. Although livestock producers have the best intentions when treating their animals for parasites, routine and frequent treatment has contributed to reduced dewormer efficacy, or resistance. With current practices of routine, non-selective administration of dewormer multiple times per year, it is possible that livestock producers are 1) administering dewormer to animals that do not actually need to be dewormed; or 2) administering a product with reduced efficacy. Both situations perpetuate the development of dewormer resistance and contribute to economic loss. The economic loss associated with dewormer resistance is two-fold because it represents a direct cost to the farmer and limits the number of fully effective dewormers available in critical animal health situations.

Dewormer efficacy is determined by assessing parasite load before and after dewormer administration. A parasite load reduction of ≥95% indicates an effective treatment. Dewormer resistance has been well-documented in small ruminant production systems. While documentation of dewormer resistance is less prevalent in other species, there are reports of resistance in beef cattle (Gasbarre et al., 2015) and horses (Nielsen et al., 2018) across the United States and other countries. A recent study led by USDA APHIS researchers (Gasbarre et al., 2015) indicated that 30% of beef farms located in 19 states across the Central, Southeastern, and Western regions of the U.S. had reduced dewormer efficacy (<90% reduction). In addition, our team recently examined the efficacy of dewormers on Maryland beef farms and observed reduced efficacy on 70% of farms. Thus, it is clear that dewormer resistance is present for beef herds at both national and local levels for beef cattle.

Extrapolating these findings and using data from USDA NASS, we postulate that dewormer resistance affects over 213,000 and 815 beef cattle herds across the U.S. and Maryland, respectively. Data for small ruminants (Kaplan and Vidyashankar, 2012) would indicate that virtually all sheep and goat operations in the US (237,829 farms)and Maryland (1,053 farms) are impacted by dewormer resistance. A conservative estimate of 25% would suggest that 10,000 dairy and 115,000 equine farms are affected nationally, with 84 dairy and 130 equine farms affected in Maryland. Because dewormer resistance is an issue at the parasite-level, farms of all sizes are expected to be impacted.

Solution and Benefits

In order to mitigate the development of dewormer resistance in livestock production systems, farmers should take measures to evaluate and adjust their parasite control program. Adoption of new management strategies will reduce the reliance on dewormers to help preserve dewormer efficacy, reduce costs associated with the development of dewormer resistance, and improve environmental stewardship of livestock operations. Data from small ruminants have indicated that several approaches can both reduce reliance on dewormers and slow the development of dewormer resistance simultaneously (Kaplan, 2020). Such approaches include developing an understanding of current dewormer efficacy on a farm, adopting a selective treatment approach, administering dewormer properly, and utilizing non-drug strategies (Kaplan, 2020). Evaluation and monitoring the current parasite management program is a critical first step to making adjustments to the program. This served as one focal point for this project, and participants were coached individually on how to perform this task. Adoption of selective treatment strategies is another critical aspect of the parasite management program that encourages judicious dewormer use. Program participants were made aware of the various selection strategies available and the project team assisted participants in selecting a strategy that was most appropriate for each individual operation. Failure to comply with appropriate dewormer application protocol, especially under-dosing, also significantly contributes to the development of dewormer resistance (Kaplan,2020). To that end, explanations for and demonstration of proper dewormer administration were provided to program participants in order to show how under-dosing can be avoided. Perhaps an over-looked, but nonetheless crucial non-drug component of the parasite management program is pasture management (Burke and Miller, 2020). Throughout the duration of this project, the project team assisted participants in developing or modifying their pasture management to help mitigate parasite exposure. Last but not least, the research component of this project generated data to highlight different pasture management strategies and their effects on apparent animal parasite load. Results from these studies demonstrated that pasture management does make a difference and are being added to the overall body of literature that pertains to the effects of pasture management on parasite load. Adoption of these aforementioned parasite management practices will improve the effectiveness of dewormers over time, as indicated through the fecal egg count reduction test, and reduce the amount of dewormer that is unnecessarily applied. At the farm-level, this translates to reduced costs associated with the purchase and application of dewormers.

Objective

The objective of this project was to teach livestock and equine producers in Maryland how to implement best practices for intestinal parasite management and reduce reliance on dewormers through a combination of direct (on-farm consultations, field days, demonstrations) and indirect (articles, webinars) methods.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

The goal of this research was to provide data that highlights the impact of different pasture management approaches on apparent parasite load of livestock. We hypothesized that implementing improved pasture management with rotational grazing and improved forage varieties would reduce the apparent parasite load of pregnant dairy heifers relative to heifers managed under a continuous grazing system. We also hypothesized that adopting annual forages would reduce the apparent parasite load for beef cattle and sheep in a mixed species grazing system relative to those managed on perennial pasture only.

Research for this project took place at two separate sites utilizing either pregnant dairy heifers at the University of Maryland Dairy Farm in Clarksville, MD (Site 1; 2022-2023) or a mixed beef cattle/sheep herd at the Western Maryland Research and Education Center in Keedysville, MD (Site 2; 2023-2024).

Treatments

At Site 1, pregnant dairy heifers (n=110; 2022-2023) were evenly allocated to one of two treatments: control (continuous pasture) or rotational grazing. The treatments for this study were selected to assess the extent to which implementing improved pasture management practices affect parasite load on dairy heifers. The control treatment was designed to reflect the traditional housing and feeding methods of dairy producers in this region and across the nation. The rotational grazing treatment was designed to utilize good grazing management practices that could reasonably be implemented on many dairy herds.

At Site 2, growing beef cattle (n=38; 2023-2024) and lambs (n=65; 2023-2024) were managed in two mixed-species groups each consisting of 19 cattle and 30-35 lambs (annually). Each group was allocated to one of two treatments: perennial pasture only or a combination of perennial and annual pastures. Treatments were selected to determine if the current trend of integrating annual forages to boost forage production has implications for parasite load on livestock. It is well-established that certain types of perennial forages, mainly those containing condensed tannins, such as Sericea lespedeza, can help control gastrointestinal parasites. However, there is little data on whether the incorporation of annual forages into a grazing system would affect parasite load. Due to the need to reestablish annual stands each year, it was hypothesized that these forages might limit parasite proliferation and thereby reduce livestock exposure to parasites. These treatments, therefore, were designed to further our understanding of whether annual forages could be used as another tool to manage parasites in grazing livestock systems.

Methods

At Site 1, heifers on the control treatment had unrestricted access to a single pasture consisting of mostly tall fescue forage (~6 acres). In addition to pasture, these heifers were fed a total mixed ration once daily to meet the majority of their nutritional requirements. Heifers on the rotational grazing treatment were managed on a pasture consisting of tall fescue (~12 acres) and annual forage (~8 acres). Pastures for the rotational grazing treatment were subdivided into smaller paddocks of approximately 0.5 acres each to facilitate rotational grazing. Heifers in this group were rotationally grazed throughout the grazing season, with rotations occurring approximately every 1-3 days depending on forage availability. These heifers also received a mineral/concentrate mix (1 pound per day) consisting of ground corn and minerals to ensure adequate mineral consumption. The grazing period varied slightly based on growing conditions but occurred from approximately April – December each year (2022-2023).

At Site 2, pastures for both treatment groups were subdivided into smaller paddocks of approximately 0.5-1 acres each to facilitate rotational grazing. Animals in both treatment groups were rotationally grazed throughout the growing season, with rotations occurring every 1-4 days depending on forage availability. Animals in both groups also had access to free-choice minerals throughout the study. The grazing period varied slightly based on growing conditions but occurred from approximately April – November each year (2023-2024). For the perennial/annual combination pasture system, perennial forages and annual forages were grown in separate areas of the pasture and animals were rotated between the areas according to forage growth and availability. The portion of the pasture containing annual forages was rotated between winter annuals and summer annuals which were established in the field in either late summer/fall (winter annuals) or early summer (summer annuals) using a no-till drill.

Data Collection and Analysis

Animals at both sites were weighed every other week throughout the respective grazing seasons in order to monitor performance. Both research sites were equipped with a livestock handling system (separate systems for cattle vs. sheep) and used a livestock scale located within the handling system to collect animal weights. At each weigh day, manure samples were also collected from each individual animal for fecal egg count analysis. Samples of manure (~100 grams) were collected directly from the rectum of each animal by trained personnel and stored in the refrigerator until overnight shipment to Virginia State University. Personnel at Virginia State University determined the number of eggs within each sample using the three-chambered McMaster technique (George et al., 2017). Fecal egg counts were statistically analyzed to assess the effect of treatment. Data was analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

Farmer Input

One member of the advisory committee expressed substantial interest in exploring the effect of forage type or forage species on parasite load in livestock. Although the project team was not able to investigate the effect of specific forage species on fecal egg counts due to constraints related to pasture establishment (all pastures were already established prior to this study and contain a mix of forage species), this does indicate that there is interest in exploring the possibility of incorporating different forages as part of the parasite management program. Through interactions with beef farmers during our team’s assessment of dewormer resistance in 2020 (Potts et al., 2021), farmers often inquired about the effect of different pasture management practices on parasite load. These studies are providing data to help justify recommendations for changes in pasture management in the context of parasite control.

Year 1 research at site 1 commenced on April 1, 2022. Dairy heifers (n=51) were enrolled in the study after confirmation of pregnancy and assigned to one of two treatments: control or rotational grazing. Control heifers (n=25) were housed as one group on a single, 6-acre pasture consisting of mostly tall fescue and white clover. These heifers had continuous access to the entire 6-acre pasture for the duration of the season. A total mixed ration consisting of mostly corn silage, small grain silage, and hay was delivered to these heifers in the field once daily to meet nutritional requirements. Rotational grazing heifers (n=26) were housed as a single group on 20 acres of pasture that was divided into 0.5-0.75 acre paddocks. Heifers in this group were moved from one paddock to another approximately every 1-3 days and were fed a grain/mineral supplement once daily at a rate of 1 lb/head/day. Approximately 8 acres of this pasture was comprised of annual forages (triticale/ryegrass/oats/crimson clover as a winter annual grazed in spring/fall, sudangrass/cowpeas as a summer annual grazed in summer) and the remainder of the pasture consisted of perennial pasture that was mostly tall fescue. Heifers remained on their respective treatments until approximately 3 weeks before they were due to calve. Because heifers were enrolled and removed from the study according to their stage of pregnancy, the number of animals in each treatment was dynamic throughout the season. However, stocking rates were maintained equally between the control and grazing group so that at any given time, there was a similar number of heifers on each treatment. Heifers were weighed and measured (hip height, BCS) and manure samples were collected for fecal egg count analysis every 2 weeks throughout the study. The final weigh day and last day of grazing for 2022 was December 19, 2022.

Year 2 research at site 1 commenced on March 29, 2023. In 2023, a total of 59 heifers were used for the study (n=29 control; n=30 grazing). Methodology remained the same as the previous year (described above). Year 2 research at site 1 was completed on December 21, 2023. This wrapped up the data collection at this site.

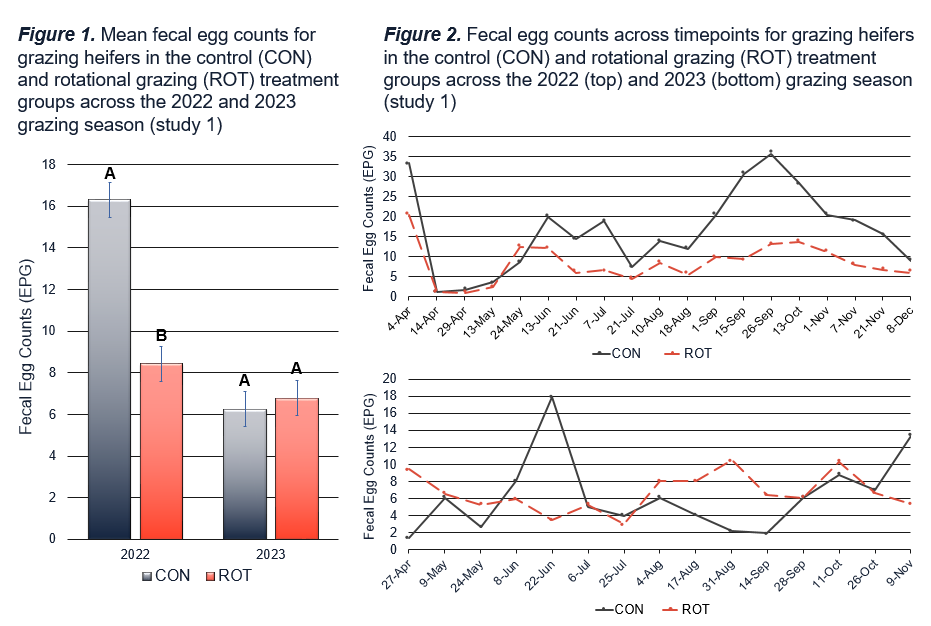

Data for this study was analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05. Graphs showing the fecal egg count data by treatment and across timepoints for heifers in the control (CON) and rotational grazing (ROT) treatment groups across the 2022 and 2023 grazing seasons are depicted below. Heifer fecal egg counts were lower for heifers in ROT compared to CON in 2022 but did not differ across treatment groups in 2023 (Figure 1). However, heifer fecal egg counts for both groups remained low (< 30 epg) throughout the study. Fecal egg counts were affected by time and varied throughout the grazing season (Figure 2).

Year 1 research at site 2 began on May 2, 2023. A total of 19 calves and 30 lambs were brought to the research farm from a local cooperator farm and were rotationally grazed as two mixed-species herds. The perennial-only group (n=15 lambs; n=9 calves) was rotationally grazed on approximately 13 acres of perennial, cool-season grass pasture comprised of mostly orchardgrass, tall fescue, clover, and alfalfa. The perennial/annual group (n=15 lambs; n=10 calves) was rotationally grazed on approximately 13 acres of pasture, part of which was perennial cool-season grass pasture (same forage species as perennial group) and part of which was planted into annual forages for grazing. The portion of the pasture containing annual forages was rotated between winter annuals and summer annuals; while not a main goal of this project, a number of different annual forage mixtures were included to be able to evaluate which annual mixtures performed better and/or were more preferred by the grazing animals. Both groups of animals were weighed and assessed (BCS, FAMACHA© score for the lambs) and manure samples were collected for fecal egg count analysis every 2 weeks throughout the study. The original plan was to graze both groups of animals into December; unfortunately, in 2023 there was a fairly severe drought in the area for a good portion of the summer. Due to limited forage growth and a lack of forage for grazing, the final weigh day and last day of grazing for 2023 was September 26, 2023.

Year 2 research at site 2 began on April 1, 2024. In 2024, a total of 19 calves and 35 lambs were again sourced from a local cooperating farm and were brought to the research farm to be rotationally grazed as two mixed-species herds. Methodology remained the same as the previous year (described above), and although it was another dry year we were able to continue grazing through November 12, 2024. The end of 2024 wrapped up the data collection at this site.

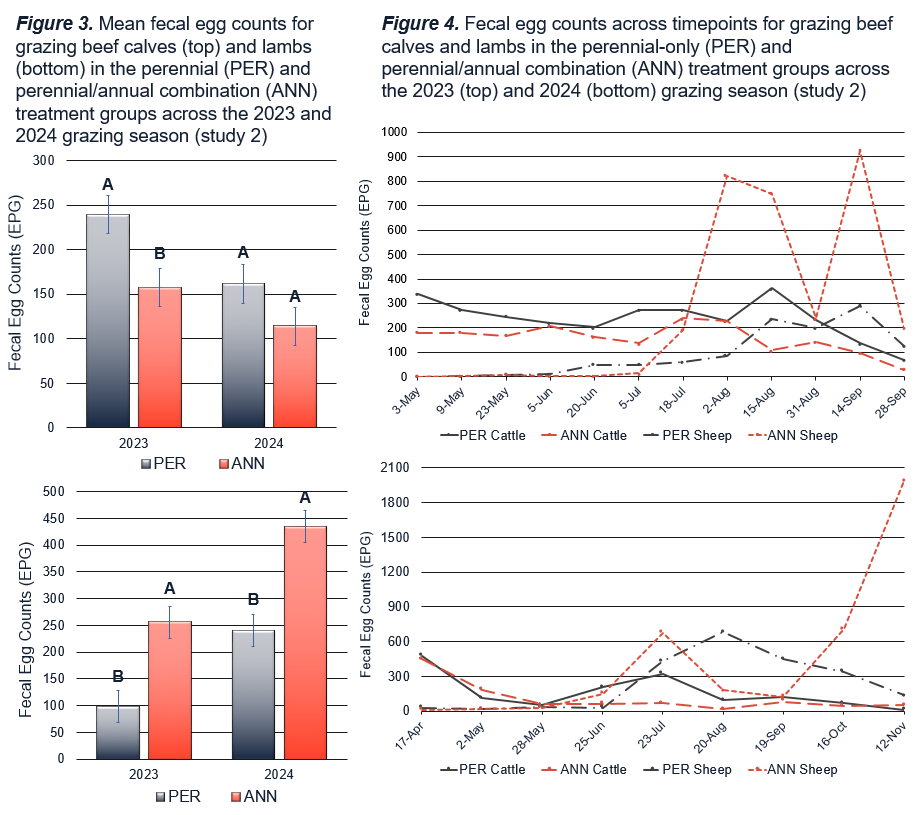

Data for this study was analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05. Graphs showing the fecal egg count data by treatment and across timepoints for the cattle and sheep in the perennial-only (PER) and perennial/annual combination (ANN) grazing systems across the 2023 and 2024 grazing seasons are depicted below. Lamb fecal egg counts were higher for ANN (256-435 epg) compared to PER (98-241 epg) in both years (Figure 3). Cattle fecal egg counts were higher for PER (239 epg) compared to ANN (158 epg) in 2023 but did not differ in 2024 (Figure 3). As expected, fecal egg counts were affected by time and varied throughout the grazing season (Figure 4). FAMACHA© scores were the same for lambs grazing in both systems in both 2023 and 2024.

Overall, based on the data from this project it is evident that livestock parasite loads were affected by both time of year/weather conditions and also by grazing management. Although fecal egg counts remained low for both treatment groups throughout study 1, the rotational grazing system did offer advantages in mitigating parasite loads for grazing dairy heifers. In study 2, incorporation of annual forages into the grazing system did affect fecal egg counts for both beef cattle and sheep. Calves rotationally grazing across a combination of perennial and annual forages showed lower fecal egg counts compared to their counterparts grazing only perennial forages. However, this same effect was not true for the lambs. The project team believes this may be because 1) calves tended to graze taller forages when on annual forage pastures while lambs often grazed lower in the canopy, and 2) rotation of animals to the next paddock may have been slower when animals were on annual forage pastures simply due to the volume of forage material available. These effects could likely be mitigated if paddock sizing was adjusted smaller to keep animals moving to new areas more frequently. Conclusions from this project are that rotational grazing systems with more frequent moves may be advantageous in mitigating this and reducing parasite loads for grazing livestock.

Education

Engagement

Farms were recruited to participate in this program through University of Maryland Extension email lists, newsletters, agents, and social media pages, as well as interactions at meetings, events, or presentations. The project team provided one-on-one visits to individual farms to help them implement two or more alternative parasite management strategies. The team also hosted on-farm field day events and open-house field day events at the research sites to discuss parasite management strategies and highlight one or more of these strategies in-practice.

The farms that participated in one-on-one farm visits consisted of cattle (dairy or beef), camelids, small ruminant (sheep or goat), or mixed species farms. Producers interested in one-on-one consultations were instructed to contact members of the project team first to ensure a mutual understanding of the program in its entirety, including goals, potential benefits, and expectations. The project team then worked with each enrolled farm to coordinate two farm visits approximately 14-21 days apart. Two or more project team personnel were present for each consultation to provide instruction, gather information for parasite management plan development, and collect manure samples for a fecal egg count reduction test. After the second consultation, each producer received an individualized parasite management plan with recommendations for their farm. Results from their fecal egg count reduction test were provided and included an individualized interpretation and suggested adjustments. Producers also had the opportunity to submit up to two manure samples for egg count analysis free of charge during the year after their one-on-one consultations. Project team members were (and still are) available via phone, email, or text message to continue providing support during the adoption of proposed management changes and to help interpret fecal egg count results.

A total of 8 field days were held throughout the project, including events on producer farms across the state and at the research site. The field days were relatively informal, field-based events. Discussion was encouraged, and peer-to-peer learning was emphasized, particularly at field days hosted on producer farms. Topics that were covered varied from event to event but included subjects like pasture management, parasite management, and dewormer selection and evaluation. In addition to these more informal events, a full-day parasite management workshop was held at the research site in 2025. Topics for this workshop included an overview of parasites and potential problems, managing dewormer resistance, fecal collection and fecal egg counts, putting together a deworming kit, minimizing parasites on pasture, calculating dosages and drenching, body condition scoring, and FAMACHA© scoring. Participants at the workshop had a chance to use microscopes to complete a fecal egg count and get hands-on practice with body condition and FAMACHA© scoring. A certified FAMACHA© instructor was present so participants could also get their FAMACHA© certification if they chose to. Participants also went home with a binder full of information and handouts about the topics covered at the workshop.

Overall, there was a lot of interest from livestock producers in parasite-related education. Altogether, the team engaged with 489 producers throughout the duration of the project. Due to continued interest from producers, the team plans to continue to engage with producers on these topics beyond the end of this grant and will likely be hosting some additional parasite management workshops in the future.

Learning

Participants at educational events were given instruction on each of five major areas related to parasite management. The participants enrolled in the one-on-one consultations also had the benefit of having individualized, hands-on instruction tailored to their specific farm to help them understand how they could apply these practices. The field day participants were provided instruction and support materials related to each of these areas and had the opportunity to observe and ask questions about specific practices implemented by each host farm.

- Pasture management: Farmers gained an understanding of how pasture management impacts parasite load of animals. They learned strategies to help reduce parasite load through changes in pasture management, including: adequate pasture rest, prevention of overgrazing, utilization of a multispecies grazing system, and forage selection.

- Parasite load: Farmers gained an understanding of approaches used to assess the current parasite load of an animal or a group of animals. They learned how to utilize fecal egg count analyses to help them determine if and when dewormer treatment may be necessary.

- Targeted deworming: Farmers gained an understanding of how targeted administration of dewormers can preserve dewormer efficacy. They learned how to determine which animals to deworm based on fecal egg count analysis, animal risk-factors, animal performance, and FAMACHA© score (when applicable).

- Dewormer selection and application: Farmers gained an understanding of the different classes of dewormers and how errors associated with dewormer application can contribute to resistance. They learned how to interpret product label instructions related to dose determination, route of administration, and residue warnings.

- Dewormer evaluation: Farmers learned how to assess the effectiveness of the dewormers that they are using through the use of a fecal egg count reduction test. Instructions for completing this test were demonstrated and assistance with result interpretation was provided.

Evaluation

Assessment of knowledge gained and evidence of planned management changes by field day/workshop participants was verified through post-event surveys administered on paper at the end of the event. The evaluation form was set up as a brief 1-2 page questionnaire containing questions on program quality, program satisfaction, usefulness of the information provided, knowledge gains, and anticipated outcomes based on the information presented/learned. Participants were also asked what they liked or disliked about the program and were provided an opportunity to make comments or suggestions for improvements or to indicate future topics of interest. Actual changes producers made to their parasite management as a result of this program have been documented by following up with producers after their second consultation or attendance at a field day event.

Program feedback was very positive, with 100% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that the subject matter was presented clearly, that the program met their expectations, and that they were satisfied with the handouts provided. Responses indicated that 94% of participants found the information useful in the management of their operation and noted an improvement in their ability to make informed decisions regarding their operation. When asked what they liked most about the program, comments included: "hands-on experience", "the willingness of the teachers to talk and answer questions", and "the instructors knowledge".

The completed program evaluations also demonstrated an increase in knowledge gained by participants. Respondents were asked to rate their knowledge of the subject(s) before and after the program using a Likert scale (1 = very little to 5 = very much) The average Likert rating was greater after program completion (average ± SD; 4.19 ± 0.77) compared with before (2.67 ± 0.98). The greatest learning gains were reported for performing fecal collections and fecal egg counts, putting together a deworming kit, and minimizing parasites on pasture. Most notably, 94% of respondents stated that they planned to make at least one change in their operation based on the information presented/learned at the event.

Milestones

- Milestone 1 (Engagement): Farmers were recruited to participate in one-on-one consultations during year 1.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 18

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers answered a short questionnaire to document their interest. Communication about the program in its entirety, including goals, potential benefits, and expectations for participation was carried out via email rather than a phone interview as was previously described.

- Proposed completion date: 5/1/2022

- Actual completion date: 6/24/2022

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 2 (Learning): Project team completed one-on-one consultations for year 1.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 8

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers learned how to apply the components of a successful parasite management program on their farm. They learned how to administer dewormers appropriately and conduct a fecal egg count reduction test. Although 18 farms completed the questionnaire, it was difficult to coordinate a date for the evaluation with some of them, so not all farms ended up participating.

- Proposed completion date: 11/15/2022

- Actual completion date: 10/27/2022

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 3 (Engagement): Parasite management plans were completed for year 1 participant farms.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 8

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers participating in year 1 received a individualized parasite management plan for their farm which included results and interpretation of their fecal egg count reduction test, recommendations from the project team, and materials to help them implement or modify parasite management practices on their farm. These plans were distributed in early 2023.

- Proposed completion date: 3/1/2023

- Actual completion date: 3/1/2023

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 4 (Engagement): Farmers were recruited to participate in one-on-one consultations during year 2.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 15

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers answered a short questionnaire to document their interest. Communication about the program in its entirety, including goals, potential benefits, and expectations for participation was carried out via email. Initial engagement of farmers for this milestone was delayed due to the project PI having a baby and being off for maternity leave in early 2023, then further delayed when the project PI left her position at UMD during the summer of 2023. Farms that had submitted the questionnaire in 2023 were contacted about the delay and the project team followed up with them in 2024, while also recruiting additional interested participants.

- Proposed completion date (new): 5/1/2024

- Actual completion date: 12/1/2024

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 5 (Evaluation): Administer 12-month follow-up evaluation for year 1 farms.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- What farmers learned or did: The plan was to follow up with farmers and ask them to complete a 12-month follow-up survey to document changes in their parasite management as a result of their participation in the program. Unfortunately, due to several major delays throughout the course of this project (maternity leave, several team members leaving their positions with the University, paternity leave, etc.), farms have not yet received their follow-up evaluation. That said, the project team has continued to communicate with the producers involved in this portion of the project and has been able to follow up with the producers and answer questions, address concerns, provide additional advice, etc. through a combination of phone and email communications. Many of the producers that participated in this portion of the project have also continued to grow their knowledge and further connect with the project team by attending additional pasture walks, field days, and/or the parasite management workshop the team hosted in 2025. One of the farms ended up hosting an on-farm pasture walk with the project team in 2024, one has been working with the project team to redesign her pastures for better grazing/parasite management, and one is interested in hosting future events at her farm with the project team. Overall, the one-on-one consultations part of this project served as a great way to connect the project team to producers across the state wanting additional guidance related to parasite management, and that relationship has continued and will continue moving forward beyond the life of this grant. Although the grant has now ended, the project team is still planning on following up with all of these participating farms in the future.

- STATUS: Incomplete

- Milestone 6 (Learning): Project team will complete one-on-one consultations for year 2.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 5

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers learned how to apply the components of a successful parasite management program on their farm. They learned how to administer dewormers appropriately and conduct a fecal egg count reduction test. Although 15 farms completed the questionnaire, several project delays described above (maternity leave, several team members leaving their positions with the University, paternity leave, etc.) combined with the busy schedule of many of the farmers meant it was difficult to coordinate two consecutive dates for the evaluation with some of them, so not all farms ended up participating. For those farms that were interested but did not get the chance to participate yet, the project team is still working with them and guiding them through the process beyond the life of the grant.

- Proposed completion date (new): 9/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 11/1/2025

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 7 (Learning and Evaluation): Recruit participants and plan two on-farm field days during year 2.

- Proposed number of farmers: 50

- Actual number of farmers: 47

- What farmers learned or did: The project team conducted several on-farm field days in 2024, at which farmers were able to learn about the components of a successful parasite management program. Attendees also got a chance to interact with the host farmer to learn about their experiences.

- Proposed completion date (new): 12/31/2024

- Actual completion date: 12/31/2024

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 8 (Engagement): Complete parasite management plan for year 2 participant farms.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- Actual number of farmers: 5

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers participating in year 2 received an individualized parasite management plan for their farm which included results and interpretation of their fecal egg count reduction test, recommendations from the project team, and materials to help them implement or modify parasite management practices on their farm. These plans were distributed in fall 2025.

- Proposed completion date (new): 11/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 11/1/2025

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 9 (Learning and Evaluation): Recruit participants and plan two on-farm field days during year 3.

- Proposed number of farmers: 50

- Actual number of farmers: 83

- What farmers learned or did: The project team conducted several on-farm field days in 2025, at which farmers were able to learn about the components of a successful parasite management program. Attendees also got a chance to interact with the host farmer to learn about their experiences.

- Proposed completion date (new): 10/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 11/1/2025

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 10 (Learning and Evaluation): Recruit participants and plan one open-house field day at one of the research sites during year 3.

- Proposed number of farmers: 50

- Actual number of farmers: 20 (2024) and 39 (2025) = 59 total

- What farmers learned or did: Farmers attended a field day at the research station during the summer of 2024. At this event, attendees were able to learn about the components of a successful parasite management program. The event included a tour, discussion on the research project, and opportunities for questions. Although the event went very well, attendance was a little bit lighter than the project team had hoped for. As a result, the project team hosted two additional events at the research station in the fall of 2025. The first was another field day, which was similar to the previous one and included a tour, discussion and updates on the research project, and opportunities for questions. The second was a full-day parasite management workshop that covered a wide range of parasite management related topics and included both classroom presentations and hands-on training in the field. A post-workshop evaluation was completed by attendees of the parasite management workshop to evaluate learning gains and participant plans moving forward.

- Proposed completion date: 9/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 11/30/2025

- STATUS: Complete

- Milestone 11 (Evaluation): Administer 12-month follow-up evaluation for year 2 farms.

- Proposed number of farmers: 15

- What farmers learned or did: Similar to year 1 participating farms, the plan was to follow up with farmers who participated in the year 2 one-on-one consultations and ask them to complete a 12-month follow-up survey to document changes in their parasite management as a result of their participation in the program. Unfortunately, as described above, due to several major delays throughout the course of this project (maternity leave, several team members leaving their positions with the University, paternity leave, etc.), participating farms have not yet received their follow-up evaluation. That said, as mentioned above, the project team has continued to communicate with the producers involved in this portion of the project and has been able to follow up with the producers and answer questions, address concerns, provide additional advice, etc. through a combination of phone and email communications. Many of the producers that participated in this portion of the project have also continued to grow their knowledge and further connect with the project team by attending additional pasture walks, field days, and/or the parasite management workshop the team hosted in 2025. One of the farms ended up hosting an on-farm pasture walk with the project team in 2024, one has been working with the project team to redesign her pastures for better grazing/parasite management, and one is interested in hosting future events at her farm with the project team. Overall, the one-on-one consultations part of this project served as a great way to connect the project team to producers across the state wanting additional guidance related to parasite management, and that relationship has continued and will continue moving forward beyond the life of this grant. Although the grant has now ended, the project team is still planning on following up with all of these participating farms in the future.

- STATUS: Incomplete

- Milestone 12 (Evaluation) Administer 6-12 month follow-up evaluation for participants in field days and open house during years 2 and 3.

- Proposed number of farmers: 150

- What farmers learned or did: Due to the project delays described above and the fact that field days and open houses were completed later than initially planned, follow-up evaluations were not sent out to participants of these events. However, the project team did get some very valuable feedback from producers who attended the full-day parasite management workshop held in 2025 and will share feedback from that. Additionally, although the grant has ended, the team would still like to complete a more formalized follow-up evaluation for all producers involved in this project and may still complete this in the future.

- Proposed completion date: 11/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 11/30/2025

- STATUS: Completed

- Milestone 13 (Learning and Evaluation): Recruit participants and give 2 outreach presentations at Maryland Extension Winter Meetings.

- Proposed number of farmers: 60

- Actual number of farmers: 213

- What farmers learned or did: Final results obtained from both research studies completed as part of this project and the team's recommendations based on research findings have been shared with farmers through several different means. Locally, information on managing pastures to mitigate parasite concerns was included in presentations given at a pasture and soil health update in the fall of 2025 and at the Maryland forage conferences in January 2026. A poster showcasing the results from this project was also put together and presented at the American Forage and Grassland Council annual meeting in January 2026.

- Proposed completion date: 11/1/2025

- Actual completion date: 1/25/2026

- STATUS: Completed

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

54

1 change to their parasite management program

1080 animals, 2500 acres

Cost savings of $3/head/year

17

At least one change related to parasite management. Examples include: monitor herd/flock health status regularly, deworm only as needed to minimize dewormer resistance, collect fecals and perform fecal egg counts, put together a deworming kit, utilize pasture management to minimize parasite issues, make improvements in grazing management, body condition score animals regularly, FAMACHA score animals regularly

460 animals; 300 acres

Greater animal health, more targeted dewormer use instead of routine administration, improved pasture management

One portion of this project involved consulting with farmers individually regarding parasite management. In addition to discussing best management practices and addressing farmer concerns, these consultations also involved collecting and analyzing manure samples for signs of parasites before and after dewormer application to assess dewormer efficacy. After the consultation visits (2 per farm), we provided each farm with an individualized parasite management report with suggestions for making improvements as well as additional resource literature.

A total of 13 individual farms have participated in this part of the project. These farms consisted of beef cattle (n=4), sheep (n=2), dairy cattle (n=1), goats (n=1), camelids (n=1), and mixed species (n=4). Together, these farms collectively manage ~830 animals. One of the benefits of this program targeting multiple livestock species has been our ability to make parasite management recommendations for farms who have more than one species on site. For example, for the farm participants housed both cattle and sheep, and we were able to evaluate parasite programs for both species simultaneously. Furthermore, several of the farms we worked with had large enough herd/flock sizes to enable us to test the efficacy of multiple dewormers, which allows for a more informative parasite management report and recommendation.

The plan was to follow up with all of these farms and ask them to complete a 12-month follow-up survey to document changes in their parasite management as a result of their participation in the program. Unfortunately, due to several major delays throughout the course of this project (maternity leave for PI, several team members leaving their positions with the University, paternity leave, etc.), completing these visits took much longer than anticipated and the project team ran out of time to send out these more detailed follow-up evaluations. That said, the project team has continued to communicate with the producers involved in this portion of the project and has been able to follow up with the producers individually and answer questions, address concerns, provide additional advice, etc. Many of the producers that participated in this portion of the project have also continued to grow their knowledge and further connect with the project team by attending additional pasture walks, field days, and/or the parasite management workshop the team hosted in 2025. One of the farms ended up hosting an on-farm pasture walk with the project team in 2024, one farm has been working with the project team to redesign her pastures for better grazing/parasite management, and one farm is interested in hosting future events at her farm with the project team. Overall, the one-on-one consultations part of this project served as a great way to connect the project team to producers across the state wanting additional guidance related to parasite management, and that relationship has continued and will continue moving forward beyond the life of this grant. Although the grant has now ended, the project team is still planning on following up with all of these participating farms in the future.

In addition to the one-on-one consultations, the project team held several on-farm field days and several field days/workshops at the research site during 2024-2025. Feedback from these events was very positive. Program evaluation surveys that were completed by participants following these educational events showed strong evidence of learning gains due to program participation, and 94% of participants stated that they planned to make at least one change to their operation based on information learned. Based on interest in these parasite-related educational events, the project team plans to continue to host educational activities like these moving forward.

Additional Project Outcomes

As a result of the outreach and educational activities from this project, the team has acquired several new working collaborations that will be beneficial in helping with continued outreach and research activities in this area moving forward. This is helping the project team develop more regional and multi-entity collaborations that will be fruitful in furthering both educational programming and collaborative research efforts across the region. One additional grant has been submitted thus far to build upon this project.

As was mentioned in this report, the project team received positive feedback on several of the educational activities conducted for this project, in particular the parasite management workshop. The team has received several requests from both producers and agricultural professionals to conduct additional workshops in different locations across the state/region and will likely host additional workshops moving forward.

One other outcome that the project team would like to highlight that came about as a result of working on this project is the continued communication and relationships developed with producers that were a part of this project. As we mentioned earlier, the project team has continued to communicate with the producers involved in this project and has been able to follow up with them to answer questions, address concerns, provide additional advice, etc. These relationships have led to ongoing activities like the following: One of the farms ended up hosting an on-farm pasture walk with the project team in 2024, one farm has been working with the project team to redesign her pastures for better grazing/parasite management, and one farm is interested in hosting future events at her farm with the project team. Overall, this project has served as a great way to connect the project team to more producers across the state wanting additional guidance related to parasite management, and those relationships will continue moving forward beyond the life of this grant.

"This was one of the BEST workshops I've been to so far. It is incredibly relevant to current operators and very difficult to find both a McMaster and FAMACHA course in person" -Attendee of the parasite management workshop

"Thank you so very much! Plenty of handouts to take notes and refer back to. We are brand new goat owners, so everything was very helpful." -Attendee of the parasite management workshop

"I often think back to your visit to the farm last spring and the helpful recommendations you shared about the pastures—I really appreciated your time and expertise. I wanted to let you know that I’ve now secured someone to come out to install fencing and create paddocks in the main pasture so I can begin rotational grazing for the sheep. Before moving forward, I was really hoping I might ask for your professional opinion on the proposed layout, if you’re willing. I’ve attached a diagram of the current plan. If you have any thoughts on whether this setup will work well, or suggestions for improvement before installation, I would be very grateful for your guidance. Thank you again for all your help and encouragement—it really means a lot to me as I continue learning how to better manage the land and the flock." -Email from a producer following a farm visit