Progress report for LNE23-466

Project Information

Problem or Opportunity and Justification:

Tree planting in agroforestry systems offers well documented solutions to farms from moderating microclimates to increasing soil health and carbon storage. Tree planting is more complex than it might at first seem. Large scale tree planting efforts are frequently unsuccessful due to institutional ineffectiveness, a uniform view of the landscape, and the lack of inclusion of diverse stakeholders. For agroforestry efforts to sustain and thrive in the region, peer networks of tree planting farmers need to be built so that there is a support system for knowledge and cross-cultural exchange. What is needed is a shift away from just tree planting alone, and toward planting as social action.

The Project team's personal encounters with dozens of farmers and a recent survey of 120 demonstrates that farmers in the Northeast, notably NY, PA, and MA, want to and are planting trees and are interested in planting more. Survey respondents are engaged in a diverse set of enterprises: livestock (over 50%), vegetables (41%), wood products (25.1%). They produce at all scales, with 52.2% under $10k annually, 19.1% at $10,001 - $25k, and 28.4% over $25k. There is clearly interest amongst a range of scales, enterprise type, and location. 75.2% want to plant more trees but only 29.9% feel confident about how. Of proposed activities, farmers rated as “somewhat or very helpful” all of the following: Expert support with mapping and planning (86%), hands on training and skill building (81%), video and print resources/online courses (79.1%).

Solution and Approach:

Solutions to the challenges of tree planting need to be grounded and arise from the communities and individuals tending the land in a given bioregion. This project is fundamentally grounded in people and place, developing materials and training in response to the expressed needs of farmers and developing a peer-to-peer network of farmers committed to tree planting.

Activities include a series of eight facilitated listening sessions to identify farmer perceptions of trees and needs for trees, species of interest, and the support needed to be successful. A public report will share findings and provide guidance for policymakers and others in the agroforestry field. Findings will inform the development of a new curriculum based in the practice of popular education. Over 100 farmers will convene online, in-person, and at the demonstration nursery to learn skills and connect with peers. 20 farms will receive expert feedback on planting plans and receive cost-share support for planting. A demonstration nursery will be built and documented with video and print resources so others can replicate elements to increase tree planting capacity on farms.

20 diversified production farms (veggie, livestock, other) develop a robust planting plan and plant 5,000 trees on 100 acres. 15 report reduced tree planting costs of $1,000 or more as a result of increased knowledge and acquired skills.

Agroforestry tree planting is gaining great interest and available funding is increasing for tree planting on farms. Yet, established and new tree planting programs are potentially repeating mistakes from the past, focused on one-time infusions of money into tree planting projects that focus on the end of trees planted out in the field, often with low survival rates. Out project aims to build community capacity for agroforestry tree planting by engaging in listening sessions with farmers and small ecological tree nurseries to understand the components needed for capacity building. This will inform curricula and online and in person trainings to increase tree propagation and planting skills among farmer groups. Research to determine if fungi can be enhanced in nursery propagation of trees will provide further solutions to improve tree health prior to field planting. In the end, we plan to demonstrate that a tree nursery is fertile ground for community capacity building, skill building, and developing locally appropriate tree stock that provides the capacity for tree planting actions in a place for decades to come.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

Our research questions are:

What is the cost effectiveness of adding commercially available mycorrhizal fungi to tree potting mix?

Does on-farm cultivation of Indigenous microorganisms (IMOs) to tree seedling soil mixes offer a low cost option that increases microbial diversity in tree potting mix?

Does either adding commercial products or IMOs to tree potting mix improve the initial vertical growth and root structure in nursery conditions?

Does adding commercial products or IMOs to tree potting mix improve vertical growth and tree survival in field conditions?

BACKGROUND

It is well established in literature that trees need fungi to thrive in forests (Simard 2004), yet tree nursery and planting efforts rarely emphasize this essential element in their approaches to tree propagation and transplanting into field conditions, which often lack fungal communities. This is likely due to a general lack of awareness of fungi dynamics by farmers and tree planters (only recently emergent in soil science) as well as few options to economically incorporate fungi into plantings.

Commercial products are available, but the quality and composition of many are unknown and cost can be a barrier for incorporating them. Indigenous microorganisms (IMOs) are a group of living organisms that are a mix of hyper localized bacteria and fungi that inhabit the soil. IMOs have the potential to be a prime source of not only fungi but a diverse community of microbes locally adapted and may be a cost effective way for farms to bring the element to increase tree planting success.

This research contributes to the project by providing knowledge about the concept of fungal additives in tree planting, and then testing the concept to see if there are measurable benefits. If proposed methods to increase initial shoot and root growth in trees proved effective, it would mean for an investment the success rate of plantings could increase. If no beneficial effects are observed, it results in a cost savings by reducing unnecessary inputs. With either outcome, this research directly affects a critical question that affects decision making around expenses for tree planting. Participants in our workshops will get to assist in experimental set up and data collection, further enhancing the benefits of this research.

TREATMENTS

A uniform tree potting mix developed on farm will be treated in four ways:

1) no added biology

2) a reputable commercial mycorrhizal products

and

3) a locally harvested IMO culture

These mixtures will be used to plant three tree species:

1) black locust 2) black willow, and 3) hybrid chestnut

Each treatment combining potting medium and species will be replicated 6 times, for a total of 81 pots.

3 tree species

3 replicates

3 treatments

3 sampling events

= 81 total trees in research / 27 per species

METHODS

1. Harvest and Amplify local IMOs: In Spring, 2023, identify one site within farm boundary, and one local site with older forests/trees. We will construct harvest containers as outlined in literature for collecting IMO cultures. Each box is filled with three inches of steamed rice, and covered. The boxes are partially buried about 2 inches in the soil. They are left undisturbed for 4 - 7 days and then checked for healthy cultures.

Cultures initially harvested are expanded by adding cultures to a terracotta pot and mixing the rice cultures with a 1:1 ratio of brown sugar by weight. The pot is filled about ⅔ of the volume and then covered and left in a cool area away from direct sunlight for 7 days, allowing the mixture to ferment.

This mixture is laid out on a soil surface and covered with straw for anothern 7 - 10 days, being examined periodically for white growth and monitores with a composting thermometer so as not to exceed 122°F (50°C). The mixture is turned 3 - 4 times during this process and when the internal temperature has stabilized the mixture is complete.

2. Acquire mycorrhizal product, prepare potting mixes

Two generally reputable mycorrhizal products will be procured that are designed for mixing into potting mix. In May 2023, once the IMO expansion and fermentation process outlined above is complete, the aggregated culture will be applied to a uniform potting mix alongside the two commercial products and a “bare” mix. Each mixture will fill pots for three species of trees (black locust, chestnut, willow) in one gallon pots. Each pot will be labeled with a letter and number code and spaced so that record keeping is consistent in a location with the same light quality.

3. Measure monthly growth in containers

For the first season, monthly measurements for each treatment will occur and be recorded along with the unique identifier code. All pots will be watered as needed to maintain moisture at the same time duration per pot. Soil samples will be collected in May / August / October for biology analysis.

4. Plant trees in Fall, measure root mass

Trees will be removed from pots in the Fall of 2023 and the root mass will be measured in length and width and weight without soil, with each sample getting a photograph. Each tree will be tagged with a metal tag with a unique identifier. Trees will be transplanted into a prepped site at 6 foot spacing with a soil furrow and mulched with wood chips.

Treatments will be randomized so each tree is placed within the same row, but treatments are in a random order. Seedlings will be fenced with a 3D electric fence for deer protection and receive a tube around the base to prevent vole damage.

5. Tree growth measured in 2024 and 2025

During the months of June - September in two subsequent seasons, one measurement of each tree shoot and trunk caliper will be recorded one time monthly with unique identifier code. Soil samples will be collected in May / August / October for biology analysis.

DATA COLLECTION & ANALYSIS

To determine the costs associated with each method, we will track time, labor, material costs associated with the commercial vs IMO vs control treatments throughout.

Tree shoot growth will be measured monthly in pots from June - October in 2023. Root development will be measured with length, width, and weight at transplanting Fall 2023. As trees grow in field conditions, shoot growth will be measured monthly June - October in 2024 and 2025. Finally, we will collect the overall height and tree survival rates after 1 year and 2 years in the ground.

We will also attempt to observe soil microbial activity at several stages in the process, to see if any “field ready” methods prove useful. Using a 40x - 1000x digital microscope we will conduct a field analysis of the specimens and document any observations that are achievable after the soil potting mix is first created, then with a random sampling from each treatment in pots at 1, 3, and 5 months. Finally, soil will be sampled during the transplanting process and then every other month in field planted conditions in 2024 and 2025.

With each of these sampling events (in pots, at transplant, in field) we will submit a sample from each treatment to the Soil Foodweb New York lab for a soil assay of total and active bacteria and fungi content. (three samples x twelve treatments = 36 samples)

For analysis, time and material cost logs will be transferred to excel spreadsheets for comparison purposes. All growth measurements will be graphed and we will conduct statistical analysis using JMP to identify significant differences in various measures.

Photographs and short videos of the process and microscope analysis will help describe any discoveries from the process and contribute to the sharing of results.

2023 Update

Because of the timing needed to initiate a trial with compounding factors, we spent 2023 stepping back and learning more about IMO preparations and the potential to do analysis that would potentially yield better results before starting the process. We consulted with several scientists and researchers and conducted literature review (in draft form) that will be part of our final write up to better determine methods that could be achieved within the stated budget and timeframe.

The major issues identified with the planned research this year were:

1) Impracticality of analyzing soil samples to determine the diversity and presence of fungal symbionts. Soil sampling was determined to be too expensive for the budget we had allocated, and does not provide a method other farmers could adopt, which is essential to our goals. Instead, we will utilize root tip microscopy methods to assess fungi presence and changes over time. This requires we switch from seeds as originally planned to established seedlings with extensive root growth.

2) The rapid transition from potted plants to field planting meant a harder and less useful set of data, moving too fast as trees take time to grow. Instead of this transition, we will focus on growing seedlings in the nursery and conducting assessment there. This also reduces compounding effects as the plants can be maintained in a consistent set of environmental conditions.

3) Assumptions about the process need to be studied before applying them to a set of treatments to see the effect on root and shoot growth. IMO culturing is a new practice for us, and it may provide unexpected challenges along the way. Root tip microscopy is an established practice, but has not been applied in this way, so a clear protocol needs to be developed.

We are still able to answer three of the research questions posed above, but will eliminate the field question.

Our plan for the coming year is:

A) Test Root Tip analysis as a process for analyzing fungi presence and diversity on tree seedlings, also measure shoot growth monthly.

Test the process on several tree root samples using root tip and full root samples and staining with KOH/Vinegar/HCl mixtures to determine most effective practice. Develop and write up clear protocols for staining, preservation of samples. Test the photo-microscope to ensure it can capture data adequately.

Purchase 27 bare-root seedlings of each tree species (bl locust / black willow / chestnut) with well established root systems. Group each species into three subgroups of 9 trees. Conduct a baseline assessment of 3 randomly selected trees from each group at arrival for mycorrhizal colonization using microscopy and document the process using photo documentation and observational notes.

Identify three local sites to harvest forest soil from and collect IMO cultures that have established trees of the chosen species.

(mid-April) Plant the seedlings in three treatments in closed air-prune beds to create homogony in the soils. For each species, one bed is constructed at 6’x4’x20” and holds nine trees. One bed per treatment, a total of nine beds. Treatments are 100% sterile soil, sterile soil with commercial mycorrhizal inoculum, 50/50 sterile soil and forest-harvested soil

(early June) Wait 6-8 weeks for colonization, do an initial assessment of presence and abundance on three replicates of each species (27 samples

(early August) 6-8 weeks later, repeat assessment of presence and abundance on three replicates of each species (27 samples)

(early October) 6-8 weeks later, repeat assessment of presence and abundance on three replicates of each species (27 samples

At each interval above, initiate a collection of IMOs at each sample site and test process of IMO 1-4:

1: Partially cooked grain (brown rice) in a cedar box with mesh lid, cover and partially bury in healthy forest soil The box is left for ten days

2: Inoculated material is mixed with brown sugar at 1:1 ratio, fill crock 2⁄3 full and cover, leave for one week

3: Some of the IMO #2 is liquefied and mixed into a pile of bran. The bran is piled on the earth in partial shade in the forest. Pile is hydrated to about 65 percent moisture, covered with wet leaves, straw or cardboard and needs to be protected from excessive rain for two weeks.

4: IMO 4 Mixed with soil/compost at 1:1 ratio, left for 2 weeks. Then used as potting mix for seeds of black locust / chestnut as initial assessment of any effect on initial germination and growth; 2 species x 9 replications x 3 treatments same as above. Germination and initial shoot growth is measured.

2024 Update

There is a tremendous amount of learning coming from our attempt to work with IMOs as a support mechanism for tree planting. We were met with several challenges in 2024, including not being able to get an adequate quality or quantity of seedlings, especially with a root system so robust we could reliably take tip samples repeatedly. We also ran into a delay getting the wood for the air prune beds (several months delayed) and recognized that the soil we filled them with also needed time to settle and adjust. Overall, we recognized that building fungal-based communities is necessarily a long term approach, and can’t be thrown together overnight.

We were able to assemble beds for our study finally in July 2024, at the time also planting each with 3 - 5 trees of the selected species for the study, which is inadequate for the root tip method suggested above, but good from a “mother tree” perspective, where we establish older seedlings first in the beds to help promote a microbial community favorable for the next stage. Each bed was filled with about 50% topsoil and 50% compost from our spent mushroom substrate we produce on farm. It was determined that letting the beds settle, rest, and integrate would be best before taking the next step.

Additionally, rather than rely on the immense variability of the seedlings to tell us anything, we decided that we needed to start on an equal plane and focus on starting trees from seed/cuttings to compare the tree treatments (control / IMO / commercial mycorrhizal inoculant) amongst the new seedlings, since we coudn’t source reliably a uniform selection of older trees. Since we were finally able to assemble beds in July and wanted to let the “mother trees” establish and soil to settle, out attention then turned towards practicing the IMO 1 harvesting procedue at sites on Wellspring Forest Farm and at Brian Caldwell’s chestnut farm.

Reliable and consistent IMO 1 harvest also proved to be a challenge which we untook on three subsequent occasions from August - October. The process involves cooking white or brown rice and packing into cedar boxes, which we constructed from readily available fencing material from a local box store. We built nine boxes in total, so we could replicate harvest at each site, as follows:

1) three boxes within a dense willow planting at Wellspring Forest Farm

2) three boxes within a black locust planing at Wellspring Forest Farm

3) three boxes with a chestnut orchard at Hemlock Grove Farm

Literature we’ve referenced has been vague in the details of the process, so our experience with more traditional mushroom cultivation proved useful as preparing the substrate and cleaning the boxes in between trials became important. Essentially the goal is to partially bury the boxes and leave for 7 - 10 days, aiming to harvest a “pure” culture of mostly white and fluffy material. As the pictures showed, we experienced a lot of variability:

<PICS>

In between each attempt we santizied the boxes to reduce the likelihood that other contaminant molds would arise again. Our assumption is that the biggest variable is likely the inconsistency of our rice mixture, as we were cooking a large amount in on a stovetop setup and it was hard to produce a consistent batch in this method. We purchased a rice cooker to reduce this variability in the future, and are hoping for more consistent results in our next round of trials.

Our plan for the coming year is:

1) Use the rice cooker to produce a reliable and consistent rice medium for IMO one. Start sampling as soon as ambient temperatures average about 50F (May?) and

2) Start seeds of chestnut and black locust (both are on hand, in storage currently) and willow cuttings in the 9 air prune beds, will try and wait until we have promising IMO cultures for the three species but will be limited in our ability to store seed/cuttings for too long (we do have a walk in cooler to extend storage window somewhat)

3) Inoculate beds with the best cultures we can produce at the same time along with the commercial inoculants in separate beds and the control.

4) Spend 2025 making observations and documenting with photo-microscope. Possibly explore root tip analysis towards end of the 2025 growing season, or in 2026.

As we reflect on the process and progress, there is a great deal of benefit for exploring this method and hopefully developing a more detailed protocol for farmers to follow. It is possible to conclude that the harvesting process is not reliable, but we are optimistic that we can continue to refine a method of processing and verifying some effect on the tree roots. Perhaps not surprising, it takes time to build robust mycelial networks in the soil. If successful these microbial communities can be seen as “banks” of live diversity that can be drawn in for many years to come.

2025 Update

This season was all about finally actualizing and articulating the process of IMOs from start to finish, which again proved to be more complex than we imagined at the outset of this research component. Building off of discoveries in 2024, we set out to test the full set of processes from IMO 1 (collection) to IMO4 (final integration into native soil). We are pleased to report we were able to complete this process for all three of the tree species, and have developed a guide to help others replicate the process.

The downside with the reality of developing the protocols is that we were not able to sync the IMO process with seed starting, which in itself is a useful discovery. We didn’t get viable cultures from the field until early June, in theory, because there is a need to wait until soil is warm enough to see healthy cultures emerge. This, along with the learning curve of doing each step of the process meant we couldn’t align the timing of sticking willow cuttings (early spring) starting Chestnut seed (late May), or black locust seed (late May), considering we didn’t get to the third stage for any of these until early August or even September. One reason for this was because rather than do all three species at once, we tried to perfect the process for one (willow) and then replicate. All this to say, we have determined that this experiment will only reach the benchmark of clearly articulating the IMO process, but not being able to assess the application of the cultures to live plants with any observable result.

We did attempt to do a few rounds of biological analysis in collaboration with Web of Life Regenerative Land Care, who conducted a few initial sample visual scans in the fall of 2025 (results not fully analyzed as of reporting deadline) and we saved samples of the cultures to overwinter in buckets in a warm (roughly 50F) space, to see how cultures might survive and be useful in the coming growing season. The plan is to do further scanning to see if we can learn anything about the populations in each sample, but it should be clearly noted that initial scans suggest it might be challenging to discover substantial differences. This is one of the lessons learned having consulted with several soil science folks; that analysis to such a granular level is challenging. We also had hoped some meaningful level of “on farm” assessment would be possible, but were discouraged when the microscope and camera lens we purchased proved to not function properly. Chances are as we have learned, we may not have been able to see/learn much, especially without some in depth training from experts.

This isn’t to say there is no value in the process, even if we can’t verify it scientifically. We could see, very visibly in each step of the process, viable and thriving cultures, in line with the visual cues the literature suggested. Our experience with mushroom cultivation gives us a sense of what healthy cultures look like, and we certainly saw these in action. We just may not be able to offer much verification beyond a “this feels right” kind of approach to the process.

While we will complete a more thorough set of conclusions for the final report, there are several points worth summarizing now:

1) Our most substantial success was being able to fully articulate the full IMO harvesting and amplification process that we were able to replicate three times. (See attachment to the report)

2) Scientific verification is challenging, likely not feasible on a farm, and would be most useful with tests submitted to a person/lab for biological analysis, which is costly.

3) The seasonal timing of cultivating IMOs and then applying to young plants, seeds, or cuttings is really tricky to align with the realities of the temperate Northeast climate. IMO cultures likely can’t be harvested reliably until June, at the earliest.

4) We wonder, are there viable ways to preserve and propagate IMO2 so you don’t have to start at 1 each time? What are the limits of how long IMO2 can be preserved?

We have expended the funding allocated to this research portion of the project, so are limited in our ability to further pursue this in 2026, as we wrap up the educational portion of the project. However, given that we have a clear protocol we may be able to do some IMO harvests on our own, with support of our agroforestry apprentice, to see if we can learn anything further of value to share. This, along with any learnings from the completed analysis, will be offered in the final grant report.

Education

ENGAGEMENT

Relationship building and participatory learning frameworks inform our approaches, where critical reflection, analysis and collective action are emphasized. Participants are supported by a robust project team, hired facilitators, and their peers to ask questions, engage with troubleshooting, and provide feedback and contribute to sustained involvement.

Project approaches support the realities of busy farmers as they progress from listening to education to implementation while building peer-to-peer connections that increase social capital and farmer confidence to provide support with challenges and maintain engagement.

The project is introduced through a free article and webinar series based at FarmingwithTrees.org, marketing to the 120 survey respondents, listservs, and the networks of key participants, partners, and committee members.

Eight three-hour Listening Sessions are designed considering unique needs of diverse groups (i.e. Black farmers, dairy farmers, Indigenous land stewards). Through shared dialogue they center and value farmer perspectives, encourage connection, and build trust and interest in future project activities.

LEARNING

To increase access, 2 of the 3 learning approaches are open to enrollment at any point to anyone identifying as a farmer, even if they do not own and operate their own land or farm business, while the 3rd is a cohort for participants who meet the USDA definition. A draft curriculum is attached, subject to adjustments. All content is delivered using the “spiral model” from popular education.

1. The Online Course on Teachable provides a platform for education during the off season supporting farmers to develop a tree planting plan. With access to live webinars, recorded and accessible anytime, participants develop a planting plan with four components: 1) site assessment 2) tree layout 3) site prep/planting/maintenance plan 4) budget. Break-outs, forums and tutorials using Google Earth, SimpleDraw and our tree planting calculator, provide multiple methods to learn, share and conceptualize a plan.

2. Field-Based Workshops held at regional sites and our demonstration nursery emphasize skill-sharing. Portions of workshops are documented by video so participants who cannot attend can view online.

3. 20 farmers demonstrating engagement in approaches 1 and 2 can apply to the Technical Assistance Cohort (TA) to implement their planting plan. In exchange for tracking labor and material costs, this small peer-to-peer group receives direct technical support and cost-share support of $5/tree.

The table summarizes the elements of learning emphasized through our approaches.

|

Knowledge |

Awareness |

Skills |

Attitudes |

|

Tree biology, resprout, coppice, pollard, tree species profiles Forest ecology, seed dispersal, survival Mycorrhizal fungal relations, site microclimate impacts on tree placement Site prep, soil decompaction Fall vs Spring planting Connections between ecological and social relationships |

Personal goals for tree planting Habits that limit personal success Indigenous history of agroforestry and land Privilege of secure land tenure and rematriation Everyone has something to teach and learn, always Farmer-to-farmer cooperation leads to increased success |

Assessing tree seedling health/site mapping/Soil testing Propagating seeds and cuttings Nursery structures (pots, air prune, etc). Budgeting and tracking costs Proper planting (tool use, holes, protection, mulching, water) Attentive curious conversation and listening |

Tree planting is a long-term vision Local genetics are important Right tree, right place, right time Some trees will die along the way! Plant ecosystems, not trees Lessons from diverse people and lands essential to success |

EVALUATION

As farmer’s engage in the webinar and workshops they complete a short questionnaire (Part A) and knowledge/skills assessment (Part B) that serve as the verification tool for the performance target. Upon exit from the project, the participant is asked to complete Part B again and report on their achievements (see attachment). Knowledge change, skills acquired and confidence level is measured by the comparison of their intake/exit submissions.

The 20 farmer participants in the TA cohort are expected to keep detailed records of their time, material costs and support from peers and project team and a full tree planting plan including 1) site assessment 2) tree layout 3) site prep/planting/maintenance plan and 4) budget cost estimate/calculator updated with actuals (attached) and document their planting process with photo/video. At the end of installation, cost actuals will be entered into the estimate spreadsheet and compared. Exit interviews are conducted with each cohort member to collect qualitative feedback and insights.

In addition to these quantitative verification tools, Two field days are held in year three at two farms from the TA cohort to support social and qualitative project components. A farm tour, share-out of lessons learned, and “Open Space” technology enables the group to self determine activities topics for discussion and activities (Owen, 2008).

Milestones

Milestone 1: Press Release, Article, and Webinar Series

Engagement

350 farmers and service providers receive an announcement of the project, visit a website with articles and attend two free webinars, verified by website traffic, mailing list sign up, and webinar attendance/ YouTube views.

Proposed completion date: May 1, 2023

Status: COMPLETED as of 1/24/2024

Accomplishments: Initial press release was send to email list (3,000+) with 12% clicks (360 people), listervs, and posted to newly launched website FarmingWithTrees.org with sign up form (105 responses). Webinars presented at Perennial Farm Gathering 2024 (80 participants), University of Missouri Agroforestry Symposium (100 live, 200 virtual attendees). YouTube channel had 27,912 views and 551 new subscribers in 2023.

Milestone 2: Listening Sessions Held with Farmer Groups

Engagement

80 farmers participate in eight listening sessions with targeted audiences (producer type, demographic group) as well as open-ended sessions and provide input on their previous tree planting efforts, interest and perceptions of trees, species of interest, and how support can enable them to succeed.

Proposed completion date: November 1, 2023 (new proposed date: December 31, 2024)

Status: COMPLETED

Accomplishments: Listening and developing this aspect of the project has taken more time than originally anticipated. As of 1/20/2024 we have held two listening sessions (with 8 Handsome Brook Farmers and 60 farmer participants at NOFA-NY conference). More time than anticipated was required to design sessions and engage in relationship building. Outputs include an intake survey to collect quantitative data, facilitation outlines and activities for sessions.

In 2024 we held a total of seven listening sessions with 110 participants in various formats and settings, from large groups at an organic farming conference to smaller virtual sessions. We learned not only about many of the trends and patterns folks are thinking about when it comes to tree planting, but also a tremendous amount about the settings and format that best work for these sessions. A group of around 10 people and a session lasting 2 hours felt most beneficial. The chart below summarizes the sessions we conducted:

Farmer Tree Listening Sessions 2023 / 2024

|

Date |

Location |

Participants |

Facilitators |

|

10/25/2023 |

Handsome Brook Farmers, Penn Yann NY |

8 |

Steve, HBF staff |

|

1/24/2024 |

NOFA NY Conference, Syracuse NY |

60 |

Steve Gabriel, Jeff Piestrak |

|

April 7, 2024 |

Strong Roots, New Growth BIPOC Agroforestry Conference |

12 |

Steve Gabriel, Jay Smith |

|

April 7/ May 4 |

Socially disadvantaged farmer Virtual Listening Sessions |

8 |

Rafter Fergueson, Ruth Tyson |

|

5/10/2024 |

Catskill Agrarian Alliance |

8 |

Bliss, Jonathan McRay |

|

December 11 |

Essex County NY Farmers |

10 |

Steve Gabriel, Meghan Girioux |

|

December 13 |

Berkshire Ag Ventures Stockbridge, MA |

12 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

TOTAL |

122 |

As of 1/24/25 we are working to complete analysis of the documentation of these sessions to share in the report (milestone 3)

In the proposal we set the goal that 50% of listening sessions would focus on socially disadvantaged farmers. Facilitators from within will be contracted to help design effective events specific to that community. We worked with Ruth Tyson, Jay Smith, and Christa Nunez to help facilitate these discussions. Of the seven sessions, 3 were 100% socially disadvantaged farmers (20 ppl total) and 1 was 3/4 socially disadvantaged participants (6), along with a number who attended the NOFA-NY session but didn't self-identify so can't be accurately counted.

Additionally, we identified the benefit of holding smaller interviews with folks who were both farmers and nursery producers, given that the need for more tree stock has come up again and again in farmer listening sessions. We conducted an additional 15 interviews with experienced producers and are completing analysis for sharing in the report in milestone 3.

Farmer + Nursery Listening Sessions

|

Nursery/Farm |

Participants |

Interviewer |

|

|

Barred Owl Brook Farm |

1 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

|

Yellow Bud Farm |

1 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

Edible Acres |

2 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

|

Forest Exchange |

2 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

Elodie Eid |

1 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

Eliza Greenman |

1 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

BreadTree |

1 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

Black Creek |

1 |

Jonathan McRay |

|

|

Twisted Tree Farm |

1 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

|

Mace Chasm and Nicholas |

2 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

|

Jonathan Bates |

1 |

Steve Gabriel |

|

|

Alaina Ring |

1 |

Steve Gabriel |

Milestone 3: Report on Needs for Tree Planting

Engagement

Project Team completes a summary report and presents as a public document online, press release and webinar includes sharing from participants, with 100 farmers accessing the webpage, live zoom, and YouTube recording. Farmers are invited to submit additional comments that are incorporated into a final version to capture their voices, with 50 additional farmers offering feedback.

Proposed completion date: February 1, 2024 (new proposed date: May 1, 2025)

Status: COMPLETED (draft attached), with final print version available in Feb 2026 at www.MycenaTrees.org

Accomplishments: (2023) Because the listening sessions took in their development and implementation (we are moving at the speed of human trusting relationships), we are delayed on the development of this report. Rafter Ferguson did an analysis of the initial survey data from the grant proposal to assess trends and also learn how questions could be better asked in the listening session survey to generate more accurate and useful data. This resulted in a more robust survey to improve data for the report.

(2024) - we have completed listening sessions and interviews and are currently completing the analysis to share in a written report as well as during scheduled online webinars in 2025.

(2025) - after several rewrites and revising transcripts to ensure we captured all voices, we passed the draft to eight reviewers who we are grateful to have read; these were both facilitators in the original listening sessions, as well as participants. Thanks to Rafter Ferguson, Ruth Tyson, Jay Smith, Samantha Bosco, Sophia Hampton, Jeff Piestrak, and Rhiannon Wright. Additionally, we asked for extra support form Annika Rowland, who re-listening to each farmer listening sessions and helped greatly on the synthesis and review of this report. The final draft is attached to this report, with a final pubised version with layout and graphics to be published in 2026, made available at www.MycenaTrees.org.

Below are the summary points from the report findings, with the full draft attached to this report.

SUMMARY OF FARMER LISTENING SESSIONS

In 2024 and 2025, we conducted 8 listening sessions with 122 farmers and land stewards ranging from in New York, Massachusetts, and Maryland, within a bioregion we are defining as the Northeast US. Participants were either actively farming with trees, or interested in it.

A. Factors Shaping Perceptions of Trees in Farm Landscapes

Trees are more than features in the landscape. They are in (and of) culture, ecology, history, and memory. Our listening sessions revealed the breadth and depth of what trees represent.

Personal and Cultural Associations: Early life experiences influenced attitudes, ranging from joyful play and connection to seeing trees as urban nuisances. Trees are often regarded as spiritual lifelong companions in a reciprocal relationship with people.

Urban / Rural Contexts: In cities, trees are sometimes seen as infrastructure problems; lack of canopy in low-income areas is tied to systemic health inequities like higher heat and polluted air. Aspiration for equitable urban tree planting that provides free food and community benefit.

Racism and Cultural Histories: Trees hold cultural and sacred roles in many traditions, but violent histories and oppressive policies also shape relationships with trees.

B. Perceptions of Farming with Trees

Farmers recognize trees as multifunctional infrastructure providing ecological, economic, and social benefits. However, success requires community networks and collective stewardship operating on multigenerational timescales. Participants emphasized quality over quantity and reciprocal relationships over purely transactional market framings.

Multiple Benefits: Beyond food (fruits, nuts, medicinals), trees provide wind protection, erosion control, biodiversity support, livestock medicine (silvopasture), climate resilience, and profound mental/emotional benefits—keeping farmers "humble, honest, and in awe."

Community and Longevity: Tree planting both requires and creates community networks. Their multigenerational timescale frames them as legacy gifts and "social infrastructure." "We don't want isolated projects. We want networks—that's essential to agroforestry actually working."

Funding and Markets: Participants wrestled with tensions between trees as commodities and trees as relationships. They criticized corporate "greenwashing"—mass plantings without care but claims to be the solution: "Quality over quantity: don't plant 100 and lose 90. Plant 20 you can steward—and get 20 to thrive." They valued trees' non-market benefits as much as future income.

C. Barriers to Tree Planting:

For tree planting to be successful, three clear elements need to be simultaneously addressed: secure access to land by individuals or community, accessible and multi-disciplinary learning and support, and equitable and flexible funding mechanisms that work for people.

Land Tenure – "Without it, you don't plant." Half of participants lacked land ownership due to inequities and costs. Many lost trees when leases ended. Community-owned structures were proposed for multigenerational stability.

Learning & Support – "Hands-on beats YouTube every time." Farmers need demonstration sites, farm visits with stipends, and patient teaching. Lack of U.S. precedents and time constraints to learn and develop long term systems create barriers.

Funding – Recently "unprecedented" amounts, but federal funding has been drastically cut by the current administration. NRCS programs are inconsistent and staff often lack agroforestry knowledge. Eligibility criteria exclude cooperatives, reinforcing inequities. Need: funding for land access, labor, and long-term maintenance, plus revolving loan funds with 20-30 year terms.

SUMMARY OF NURSERY INTERVIEWS

Interviewing nursery growers wasn’t part of our initial SARE proposal, but after several farmer listening sessions, we realized we were leaving out a critical element in the lifecycle of trees on farms, which is who propagates them and how. Agroforestry efforts lack enough nurseries to meet future seedling needs in both quantity and quality, so we see building nursery skills and capacity as a vital element. Nurseries represent a starting point of regional agroforestry systems, as sites of genetic experimentation and agroecological care. Growers we talked to see themselves producing trees in order to shape the future resilience of regional food and farming landscapes.

In 2024, we conducted 9 interviews with 14 nursery growers, ranging from New York to Virginia, about species, scale, and cooperative structures. We started with a list of interviewees that snowballed through recommendations for others. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes with a similar set of questions, though every interview branched in multiple directions as we followed passion and insights. We also sent a short survey with more quantitative questions (e.g. current demand and gross annual sales for their trees, types of production they use, how many acres they use for nursery growing, how many trees they propagate and want to propagate annually) along with variations on the qualitative questions from the interviews.

Across interviews, one key idea stood out: a coordinated, collaborative nursery field is essential to any large-scale agroforestry future. We also interpreted several related insights by synthesizing interviews:

-

- These nursery growers often started propagating plants so they could access affordable trees, steward regionally adapted genetic diversity, and pursue promising staple crops and their support species for ecosystem function and ecological succession.

- Nursery economics span from homestead-scale supplemental income to full-time enterprises, either mid-sized or conservation-scale. Outreach, timing, and pricing are challenging and vary based on scale and markets. Most interviewees were solo operators of small and mid-sized nurseries but were interested in distributed networks and cooperative models to aggregate supply.

- Agroforestry’s disorganization (along with massive cuts in state and federal funding) constrains its growth and diversity, creating “missed connections” between seed collectors, plant propagators, and farm planters. Like so much farming in the U.S., land, capital, and infrastructure costs severely limit who can enter or scale nursery work.

- Growers named collaboration as the clearest response to the financial challenges and disorganization of agroforestry. Creating cooperative pathways for regional producers lowers the barrier for entry into the field. Three key opportunities include sharing genetic resources (including shared sourcing and grading), sharing information (including shared ethics for harvesting and pricing), and shared genetic repositories to protect access to historic orchards.

Interviewees argued that agroforestry must be treated as a coordinated movement rather than a niche or isolated enterprise. Doing so requires long-term planning, equitable financing structures, and multigenerational stewardship—conditions not currently in place but urgently needed. We wanted to contribute to these conditions with the next step of our project.

Milestone 4: Curriculum Development and Feedback

Learning

Project team refines draft curriculum for online and hands-on workshops using planning forms, activity guides, and developing handouts and educational tools. 5 farmers are compensated to review the initial draft and provide feedback before the final edition is published.

Proposed completion date: January 1, 2024 (new date: November 1, 2026)

Status: IN PROGRESS

Accomplishments: (2023) Because the listening sessions are proving longer in their development and implementation, we want to delay finalizing curriculum until we have more information. In the meantime, we have begun to assess the outline originally submitted to the grant, made updates to that, and developed a draft matrix of content and skills essential to tree propagation and planting in a spreadsheet, with links to additional supporting resources. After listening sessions are completed we can apply this matrix to develop curriculum for online and in person learning events.

(2024) Curriculum development is ongoing and informed by the listening session and interview analysis currently in process. This past year we also engaged in holding and documenting several in person learning events as a way to build out curriculum with live feedback from participants. (also relates to milestone 7). We engaged in the following events in 2024:

Agroforestry Field Day, 9/20/2024 was a facilitated tour and discussion of all agroforestry activities at Wellspring Forest Farm, which included discussion of the demonstration nursery, IMO research, and other grant activities. Tour elements were documented and mapped. (16 participants)

Tree Nursery Intensive, 10/19/2024 hosted 16 farmers and spent time at Twisted Tree Farm, Edible Acres, and Wellspring Forest Farm. We documented the entire class via audio recording and notetaking to capture the most relevant and impactful elements that can be highlighted in the curriculum.

Perennial Farm Gathering, 10/6/2024, Steve developed a talk “Why Trees Die” and presented to 80+ live and 40+ virtual participants at the Savannah Institute’s event. The talk was also released as a podcast and continues to expand reach:

https://www.savannainstitute.org/why-trees-die-and-what-we-can-do-to-help-them-with-steve-gabriel/

In working with these events, we are able to document and develop the most important elements of a curriculum on tree planting, which we plan to continue to bring together in 2025.

(2025) - we are continuing to document and organize a curriculum based on these events and in anticipation of spring and fall events planned with farmer participants in 2026. The curriculum will be a series of outputs in the final report, based on feedback from

a) farmer listening session format and questions (8 - 10 participants)

b) conference session version facilitating similar dialogue but with larger groups (30+ participants)

c) three hour "community conversations" to get clarity on values alignment, preferred tree species, etc

d) one day tree exchange workshops / demo on farms to skill farmers in tree planting and maintenance

e) Elements of an Agroforestry Tree Nursery document

Note that this milestone changed somewhat as we shifted from offering anything online, as explained below in Milestone 5.

Milestone 5: Online Course is delivered

Learning

Up to 100 farmers from the Northeast participate in an 8 week online class with 20 hours of instruction and guest presenters. Participants attend live sessions, complete follow up reading and video assignments, and work on developing a tree planting plan for their site.

Proposed completion date: March 1, 2024 (new proposed date: march 1, 2026)

Status: IN PROGRESS / SHIFTED IN 2025

Accomplishments: (2023) Because the listening sessions are delayed, we also decided as a team to delay this to Fall-Winter of 2024 - 2025. We are changing from Teachable as a platform to Circle for better access. We are opening a public forum on this platform to being discussions and hold more informal online learning events in 2024, in preparation for a cohort taking a full course in 2024.

(2024) We continue to find immense benefit in holding events and building curriculum based on the feedback of participants. We plan to continue this into 2025 and develop the online version of the curriculum along the way, with a release goal of December 2025. We found that circle was not a helpful platform (too complex) for our farmer audience with some initial attempts and are switching back to teachable as the best platform for delivery. We are developing the material so that it can be accessed asynchronous as well as be a resource for live sessions in the future.

(2025) With permission from the NE SARE team, we shifted this milestone to better align with the needs and realities of our farmer participants. Folks expressed that they were not willing or able to participate in such an online offering, typically because of a busy lifestyle and inability to commit, not for lack of interest. We proposed re-allocating the staff time to offer our 18 farmer participants on the implementation phase to offer each farm two one hour consulting sessions to more directly support tree planting planning and implementation. See milestone 8 for more details on this.

Milestone 6: Demonstration Nursery is designed and developed

Learning

Nursery elements are planned at the two sites (Wellspring Farm and Mike DeMunn’s forest) and implemented beginning with site prep and deer fencing. 60 farmer participants in workshops learn while constructing elements of the site. 200 farmers view 8 YouTube videos of nursery elements and their construction. Research begins on site in Spring 2023 and continues throughout the project.

Proposed completion date: November 1, 2024 (new proposed date - 2026)

Status: IN PROGRESS

Accomplishments: (2023) Several elements of these spaces are well underway, with the focus of 2023 on initial planning, site prep, and soil development. Deer Fence has been installed at Wellspring Forest Farm and Mike DeMunn's forest. Bed prep was initiated at both sites, with BCS tilling/bed prep, cover cropping. Woodland areas at Wellspring were cleared for additional bed development, along with space inside the field greenhouse for bottom heat cuttings and field beds were tarped for development in Spring 2023. We are documenting the process and steps for curriculum and future online and field learning events.

Design for Mike DeMunn's nursery Wellspring Nursery development. Deer fence is white line. bed prep @ Mike Demunn's Bottom heat cuttings @ Wellspring

(2024) - Much of this season was spend on the build out of beds at Wellspring for the IMO research, continued soil building at Mike DeMunn’s, and monitoring and maintenance of the 3D fences that have been installed. It has become clear through the project that a 3D fence is a deterrent, not a fortress that will keep deer out perfectly. It has become necessary, then, to keep apprised about the actual specific deer that are interacting with a site and know their habits may change over time. Management requires weekly maintenance. Still, we see the technology as useful for others in certain contexts, and this end are working on an article describing the design, installation, and maintenance of 3D fences for agroforestry.

At Mike DeMunn’s, further development of infrastructure was delayed as we tried to get a well installed for reliable water, since the site currently lacks this (other than for the house, but don’t want to strain the well). As we go, we are updating a document “Elements of an Agroforestry Tree Nursery” which will feed into the curriculum and be shared as a resource.

(2025) - We made the difficult but logical decision to cease efforts at Mike DeMunn's land, given the constraints with water access (a good call considering the short term drought we experienced July - September). The Wellspring nursery continues to be in development and plans to document nursery techniques are included in the 2026 workplan, but instead of documenting these two nurseries we will look to the wider nursery network we have cultivated and either link to existing videos or create new ones in 2026 to include the "elements of an Agroforeatry Nursery" curriculum deliverable. We developed a 3D fence article based on experience using the technology at Wellspring (attached to report).

Milestone 7: In-person Skill Building Events at partner farms and demonstration nursery

Learning

60 farmers participate in workshops at three geographically distributed sites in the region at 3 partner farms to build skills around tree planting. 40 farmers participate in hands-on workshops at the demo nursery in Mecklenburg, NY focused on building on-farm nursery infrastructure for on site tree propagation.

Proposed completion date: December 1, 2024 (new proposed date: December 1, 2026)

Status: IN PROGRESS - planned for May and November 202

Accomplishments: (2023) Due to the aforementioned delays, we are assessing the timing for holding in person workshops. Likely, we will pilot one or two this year and redesign based on feedback for future offerings.

(2024) As mentioned above in milestone 4, we hosted several events that brought 30 farmers together for connection and dialogue around the project, learning new tree planting skills. These events were held at Wellspring Forest Farm, as well as Twisted Tree Farm and Edible Acres. For 2025, we are looking at other sites in Essex County, NY and the Catskill Region / Western Massachusetts to host follow up courses and gather more farmers to learn and share. These events will also be documented for curriculum.

(2025) In April 2025, we held an in-person event in Delhi, New York, with farmers affiliated with the Catskills Agrarian Alliance. We facilitated a version of our listening sessions to understand their perceptions of the roles and benefits of trees and the barriers and challenges to planting trees alongside their other farm work. We gave away approximately 100 Amorpha fruticosa seedlings from Silver Run Forest Farm and identified farmers who were interested and ready to plant trees on their farms. Several of these farms then participated in the follow up calls.

Milestone 8: 20 Farmers form Technical Assistance Cohort

Learning

From the initial pool of participants who complete online training and attended at least one in person event and a full tree planting plan, 20 applications will be accepted for additional support for implementation from September 1, - November 1, 2024. Selections by advisory team and project leaders will select farms who are most ready to implement and represent a wide sample of how trees are being incorporated in various enterprise types and farm scales. Selected farmers form a peer-to-peer group that meets monthly from November 2024 through March 2025 to review and support planning in preparation for planting in Spring 2025.

Proposed completion date: April 1, 2026

Status: IN PROGRESS

Accomplishments: (2024) We have initiated the building of a cohort, yet it is looking different than originally proposed. Rather than one larger group, we have identified more localized partners who can build internal and connective capacity around trees and will be interested in developing the support network and engaging in tree planting projects as this grant progresses. Currently, we are developing follow up events with Essex County Farmers, the Catskill Agrarian Alliance, and the Strong Roots, New Growth (Ithaca NY area). We expect to host 8 - 10 farmers from each group and engage in dialogue, skill building, and planning for planting projects over the course of 2025.

(2025) Our focus groups and listening sessions identified two cohorts in New York who wanted trees, wanted skills training for proper planting and aftercare, had some sense of group identity that could form the base of ongoing work brigades, and included a nursery grower. Through our interviews, we realized that we should connect propagators and planters (the producers and the users in this instance) as two vital roles in the field of agroforestry to socially plan what trees were most wanted, most available, and most easy to propagate so that farmers could in turn propagate plants within their own networks once they had the confidence, skills, and plant material to work with.

In Spring and Summer 2025, we interviewed 18 farmers connected to the Catskills Agrarian Alliance and an Essex County group who had also participated in an earlier listening session. An hour-long Zoom conversation with each or the 18 farms covered several topics:

- their land boundaries and general areas of interest for tree planting locations

- capacity and seasonal pattern for planting and maintaining trees

- what trees they want to grow, how many, and site prep and protection already available or needed

- whether or not they wanted to be a plant source for other growers in their network

We’re in the process of following up with each farm for a second call to finalize tree planting plans in preparation for three late Spring field days focused on propagation and planting skills, collective planting on three sites, and distributing approximately 5000 trees sourced from 5 nurseries. Working with cohorts of farmers from our interviews ensures our research moves beyond reports to the fields and gardens where we listened, and beyond.

Milestone 9: Implementation Support for Tree Planting

Learning

15 farms implement tree planting plans on their land. Project leadership ensures at least one person attends planting events in Spring 2025, offering support via technical assistance and documenting the planting activities. The grant budget provisions to cost share each tree planted at $5/tree planted. In total, 5,000 trees are planted across 15 farms and documented with video and photos.

Proposed completion date: December 1, 2026

Status: IN PROGRESS

Accomplishments:

(2025) A necessary need for implementation, of course, is to source the trees. Rather than just ordering from random nurseries online, we took the opportunity and reflections from interviews to work on an initial process of aggregation with five nurseries: Edible Acres, Barred Owl Brook, Forest Exchange, Silver Run Forest Farm, and Wellspring Forest Farm. Based on conversations with each entity, we compared available trees from these nurseries with the desired species lists we ranked on interest (see image, below)

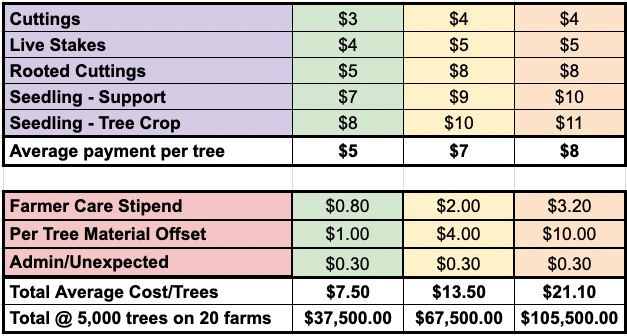

We also developed a base pricing structure to offer nurseries based on the grant funds available ($37,500) as well as an opportunity we’ve been offered by a foundation for an additional $15,000 if we can match it through fundraising to bring the total to $67,500. Finally, we projected an optimal scenario where funds would cover the trees at a better price, offer a farmer stipend for their planting and care, and cover material costs to protect each tree. ($105,500). These offer some baseline values for reflection and refining over time.

As an example, for smaller nurseries, an average of $5 - 8 per tree may not be feasible. Farmer care stipends are modest in these figures, but we did compensate additionally $125 for listening session participation and $200 for one-on-one technical support sessions, which could be lumped into the total next time. And admin costs only reflect implementation portions of this project. An additional $2 - 4 per tree is likely needed to cover the listening sessions, community conversations, coordinating aggregation efforts, and other overhead/admin.

We plan to refine this model and offer a clear cost for the whole process for the final report, including all aspects of the project in one set of figures, to offer a more realistic per tree cost for this holistic approach. The reality of how this plays out on farms in 2026 will greatly inform this!

Milestone 10: Verification of target, farmer exit interviews

Evaluation

For each successfully planted farm, actual costs are compared with estimates in budgeting workbook. Farmers meet with project leadership to review budget workbook. Knowledge/skill worksheets are compared to determine verification of performance target. 90 minute exit interviews with farmers and project leadership capture quantitative feedback from participating farms.

Proposed completion date: November 1, 2026

Status: NOT STARTED

Accomplishments: N/A

Milestone 11: Curriculum, case study, project resources published to FarmingWithTrees.org / www.MycenaTrees.org

Learning

Throughout the project, materials and updates are posted as completed to the website. By project term, 300 farmers visit the site, verified by intake form and mailing list prompt when entering. Website endures as a hub for supporting farmers interested in tree planting.

Proposed completion date: November 1, 2026

Status: IN PROGRESS

Accomplishments: Currently, a project overview, published articles, and a sign up for are posted to https://www.farmingwithtrees.org/projects/farmer-tree-skills. We will continue to build out materials here and at the circle site as the project develops.

Milestone 12: Field Day Roundtables

Evaluation

At the end of each season (2024, 2025) an open invite will be sent to the list of participating farms to join a day-long roundtable and farm tour, to be hosted at one of the farmer partners willing to host. Topics will be self determined by the assembled group, with a goal of 30 farmers attending each event for a total of 70 unique farmers over the duration of the grant. Events are partly social, low intensity gatherings with farm tour, open discussion, and sharing out of the project progress. Participants will be encouraged to share information or skills they have expertise in.

Proposed completion date: December 1, 2025

Status: SHIFTED

Accomplishments: Due to the reallocation of staff funds to individual farm support, we will not host these specific events. However, the in person events planned for 2026 will largely achieve similar results to this intended milestone, with a mix of skill building, content, tree exchanges, and social time. The planned sessions include:

May 2, 2026 : Workshop/gathering at Gael Roots Community Farm in Livingston Manor, NY

May 3, 2026: Workshop/gathering at Star Route Farm, Charlotteville, NY

May 4, 2026: Cuttings delivered and gathering at Barred Owl Brook Farm, Essex, NY

November 2026: Workshop/gathering at Mace Chasm Farm, Essex NY

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

20

Diversified production farms (veggie, livestock, other) develop a robust planting plan and plant 5,000 trees

5,000 trees are planted on 100 acres

15 farms report reduced tree planting costs of $1,000 or more as a result of increased knowledge and acquired skills.

Too early to reach this target. We are building!

Additional Project Outcomes

The most significant outcome in the project thus far is a reframing of some of our central assumptions and approach and the way that is resonating and being explored by many others in the agroforestry community. In essence, we want to avoid perpetuating the mistakes of previous tree planting initiatives, especially in the farming context where one-time cash infusions are offered to individual farms to plant trees (they don't always cover the true cost of this) but rarely to maintain them. Tree planting is a decades and lifetime long process. Rather than scattershot approaches that isolate individual farms, what has become clear is the need to build community capacity in local regions where connected networks of farmers offer and build alongside each other the knowledge, skills, and infrastructure (i.e. nurseries) to engaging in tree planting for the long term.

The offer of listening sessions for farmers and nursery producers has been welcomed and of great interest to the wider community, and we see the process as a template for ongoing long term work to help build this capacity. Listening is both important to help farmers articulate what priorities and needs arise for them, and also to build community. Because locales are each unique in their composition, there are a wide range of ways this will play out, and so the listening sessions and what follows (curricula, training, funding support) in this project must be well designed as flexible, adaptive, and iterative to remain responsive to unique situations.

As we engaged with listening sessions and interviews, it became clear that context and connectivity matters. We are pivoting away from assembling a larger cohort of individual farms towards working with existing networks that are connected socially and geographically. We will facilitate dialogue and support skill building within these communities, working towards identifying tree species of interest, then connecting with nurseries to help grow out the material, or supporting the network in growing their own material, for planting in 2026. We will be fundraising to match the $25,000 allocated in the grant ($5/tree), with a goal of raising an additional $30,000 so we can get closer to $10/tree subsidized by the project. In the end, we aim to hold the connective tissue between farmers, their local networks, nursery folks, and the knowledge and skills needed to get trees established.

What has become clear is the need to weave a deeper social fabric into the project, in order for our outcomes to be successful. Tree planting is less a technical issue, and more a social one. To this end, the project has led to the creation of a new non-profit, Mycena Agroforestry Initiative, which was incorporated in late 2024 in New York and received 501(c)3 status in mid-2025. Mycena Agroforestry Initiative’s (MAI) mission is to educate and empower farmers, land stewards, and their communities in the practice of agroforestry to create climate resilient habitats and prolific agricultural ecosystems. The initial board of directors includes Steve Gabriel, Jonathan McRay, Samantha Bosco, and Jeff Piestrak. This structure will allow elements of the project, and lessons learned, to be continued past the duration of this grant.