Progress report for LNE23-470

Project Information

50 New York farmers of all types of crops will directly participate in this project. Eighty percent of the participants will deplete their weed seedbanks based on the biology of the species present, thereby reducing weed emergence on 1,500 acres. Starting in Year 3, this will result in a combined increase in net profit of $50,000 per year due to a combination of improved yields and reduced weed management costs. An additional 50 farmers learning from the project via other means will indicate their intention to improve weed seedbank management on an additional 2,000 acres.

Weed management has long been one of the most challenging production-related issues for organic farmers, but due to increasingly variable weather, labor shortages, and herbicide resistant weeds, New York farmers of all types are struggling with weed management. Even in competitive crops, uncontrolled weeds can reduce yields by half. As a result, local educational events on weed management have been packed with attendees. Several recent polls of vegetable farmers showed that finding new solutions to weed management was their highest priority. Our recent project with conventional field crop farmers found that 97% of evaluation respondents intend to try a new management tactic due to their increasing difficulties with weeds. Clearly, the increasing challenges with weed management have created an opportunity to promote new, effective solutions.

We have also fielded hundreds of questions from farmers about how to improve control of individual weed species. And our answers depend on the biology of the weed. When does it emerge? When does it start flowering? What is the seed viability? This type of knowledge is essential for adjusting management to disadvantage key species. Several of the project key personnel have contributed to this extensive body of knowledge. But unfortunately, there is no “one size fits all” solution for weed management as every farm has a unique set of weeds and available management tools.

We aimed to address this critical challenge by providing weed management solutions that are tailored to the needs of individual farmers. Specifically, we worked with 50 New York farmers of all types to analyze their weed seedbanks – meaning all of the weed species present in the soil (in seeds, and for the purposes of this project, perennial rootstock as well) – so that we can help determine a management plan that utilizes the tools available to each farmer to address the entire suite of weeds, rather than just those that are problematic in a given year. Seedbank results and management recommendations will be provided to each farmer in a written report and the project leader will follow up to help fine-tune the recommendations to match the interests of each farmer. The reports will be publicized to 500 additional farmers to provide examples of farms using their available tools to target “Achilles heels” of weeds.

Our research component is not critical to project success but has the potential to further strengthen our tailored weed management recommendations through increased understanding of how seedbank depletion may be expedited using soil fertility, superheating, fungal enzymes, or herbicide resistance management. Finally, we will use phone-based evaluations to assess the degree of adoption and monetary impact of improved weed seedbank management.

Research

- Which aspects of field management history or soil factors correlate most strongly with abundance of certain weed species?

- Could banded applications of boiling water be used to cost-effectively reduce in-row weed seedbanks so that herbicides or cultivation would only be needed for between-row zones? Relatedly, which weed species’ seeds are not affected by superheating?

- Which fungal enzymes or cultures are most effective in degrading seed coats of various weed species?

- How widespread is herbicide resistance in New York and how strongly does the degree of resistance correlate with seedbank densities of resistant species?

We will address each research question with a small experiment.

Experiment 1.

Treatments: This project will provide an excellent opportunity to learn more about which species are most strongly associated with various management practices such as crop rotation, tillage system, fertility sources, timing of management, and whether farms are organic or conventional. Additionally, there are several well-documented cases of weed species signaling certain soil conditions – pigweed species are especially stimulated by high phosphorous environments, prostrate knotweed can tolerate compacted soils, and yellow woodsorrel can tolerate wet soils (Mohler et al., 2021) – and there may be other associations that can be used for management. We will compare the abundance of weed species to each component of a deluxe soil test as well as factors we can measure on site, such as stoniness, soil water infiltration, and soil compaction.

Methods: We will gather the aforementioned information about field history in our initial farm visits. Samples for soil testing will be collected at the same time and location as the seedbank samples. Adjacent to the sampling sites, soil water infiltration will be measured using the cylinder method and soil compaction will be measured with five penetrometer readings. There will be no plots or blocking in this experiment, but rather a statistical comparison of several continuous variables as experimental units.

Data collection and analysis: We will use multivariate ordination to explore correlations between the field history, soil variables, and densities of each weed species across all the farms.

Farmer input: This is a topic of great interest, especially among organic field crop farmers in New York. Some apply lime or micronutrients to control certain weed species and they have suggested that more research is needed in this area. The project leader co-organizes the annual New York Certified Organic (NYCO) field crops meetings and will poll the group to ensure key relationships between certain weeds and soil characteristics are investigated.

Experiment 2.

Treatments: Soil superheating has long been used to kill weed seeds. In recent years, we have observed an increase in usage (Birthisel and Gallandt, 2019; Lounsberry et al., 2020) but in the Northeast, this tactic has been confined to small-scale applications due to the high cost of labor or materials. To improve the economics, we aim to test the cost-effectiveness of superheating only the narrow band of soil where crops will be planted. If feasible, this would save herbicides or cultivation for between-row zones – reducing costs and risk of crop injury.

Methods: After primary and secondary tillage but prior to planting, water will be boiled in an electric kettle and applied to the in-row zone at rates of 0, 500, or 5000 liters per hectare. Snap beans will then be direct seeded and between-row zones will be hand hoed. The experiment will be a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Experimental units will be plots consisting of single rows, three meters long. Field usage as well as materials not listed in the budget are provided in-kind.

We also intend to screen for weed species that may be unaffected by superheating – or even stimulated by it, as we observed with common purslane in a previous trial. This will be conducted using our 50 seedbank samples after seedbank assays have been conducted. The samples will be covered and left outside to freeze overwinter to allow for a new flush of weed emergence the following spring – at which time they will be wrapped in solarization plastic for three weeks and then removed to observe weed emergence.

Data collection and analysis: In-row weed densities of the most common species will be recorded one and two months after application of boiling water. Weed control will be statistically analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. If effective, the project leader will also evaluate the economic viability of each treatment using partial budgeting analysis as he has done previously (Brown et al., 2019), but based on estimated tractor-drawn usage of commercially available water boilers.

Farmer input: Based on the input we have received from farmers about superheating soils for control of weed seeds, small-scale farmers view it as a viable tactic whereas larger-scale farmers do not. Therefore, we would like to investigate more cost-effective and scalable methods.

Experiment 3.

Treatments: We will test two proprietary fungal enzymes and ten commercially available fungal cultures for their potential to expedite the decay of weed seeds compared to an untreated control (in sensu Chen et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2009).

Methods: One-hundred seeds of redroot pigweed will be incubated in glass vials with each treatment for 24 hours. To allow sufficient time for microbial decay, groups of ten seeds of each treatment will then be separated into mesh bags and buried with field soil in flats and irrigated regularly for one year. To maximize potential for seed decay, germination will be discouraged by regularly exposing flats to far red light (Khan et al., 2022). This experiment will follow a randomized complete block design with ten blocks (flats) and mesh bags as experimental units.

Data collection and analysis: At the end of the one-year burial period, mesh bags will be exhumed, and seeds will be visually evaluated to determine if they have decayed. Number of decayed seeds per bag will be statistically compared between each treatment and the control using ANOVA and Dunnett’s tests.

Farmer input: As this is a new idea for weed management, we have only discussed it with a few farmers, but they indicated support if it proves effective.

Experiment 4.

Treatments: We have observed varying degrees of herbicide resistance in weed populations of New York. Weed species that have demonstrated resistance include common lambsquarters, common ragweed, horseweed, Palmer amaranth, and tall waterhemp. We aim to screen these species emerging from our seedbank assays for resistance to commonly used herbicides, including glyphosate, 2,4-D, glufosinate, metribuzin, and cloransulam.

Methods: If any of the suspect weed species emerge in our seedbank assays, we will repot as many as ten of each species and allow them to produce seed. Seeds will then be frozen and encouraged to germinate the following year so that we can screen the resulting seedlings for herbicide resistance. We will use 1x standard rates of the aforementioned herbicides on 10-cm seedlings. Applications will be made using our indoor spray chamber at 187 liters per hectare (20 GPA) spray volume with spray pressure and nozzles appropriate for each herbicide. Each seedling will be an experimental unit and ten seedlings will be tested per species-farm-herbicide combination.

Data collection and analysis: Two weeks after each application, weed survival of each seedling will be visually rated on a scale from 0 to 100. As this is a screening, we intend to simply calculate the average survival rate for each species-farm-herbicide combination and use it to update our understanding of the spread of herbicide resistance in New York and to improve our recommendations for the participating conventional farmers.

Farmer input: Over the past few years, conventional farmers have indicated that herbicide resistance has become the most critical production challenge to farming in New York. Several key personnel have started testing herbicide resistance and our early results have been greatly sought-after by farmers in adjusting their management.

2023 Reporting

Experiment 1. In the fall of 2023, we collected soil from 50 farms across New York. These farms represented a wide range of crops, farmer demographics, and geographical locations. Field history was discussed with each farmer as well as the timing and intensity of tillage. Soil water infiltration was not tested due to time constraints, but rather, each farmer was asked about the frequency of standing water in the field and to rate the drainage on a scale of 1 to 10 and soil compaction was measured with five penetrometer readings. Five soil samples from each field were bulk processed and submitted to DairyOne for Standard Plus testing. An additional ten soil samples from each farm were placed in sealed plastic bags and stored in a refrigerator at 4 degrees Celsius for seedbank analyses to be conducted starting in the spring of 2024.

Experiment 2. In 2023, a field experiment was implemented to test the potential for boiling water applications to kill weed seeds in advance of planting. At the Cornell University Experiment Station in Ithaca, NY, plots received 0, 50,000, or 100,00 L/ha of boiling water in a randomized complete block design with four replications at two sites. Unfortunately, there was no effect on annual or perennial weed emergence following the applications. We will adjust our methods next year to determine the rate of boiling water needed to achieve a seedbank depletion.

Experiment 3. We also conducted a preliminary study investigating the potential for microbial enzymes typcially involved in degradation of plant defenses could be applied to seeds to expedite their decay. Lots of 20 seeds were incubated for with Briton-Robinson buffer, Briton-Robinson buffer plus proprietary enzyme1, or Briton-Robinson buffer plus proprietary enzyme1 plus proprietary enzyme2. Seeds placed in nylon mesh bags and buried for six months in living field soil containers placed in darkness at 15 degrees Celsius and irrigated regularly to encourage fungal decay. No treatment resulted in any decrease in viable seed. However when samples were reburied and encouraged to germinate, germination was significantly greater for those that had been exposed to enzymes. These methods will be adjusted and further work will be done on this in 2024.

2024 Reporting

Experiment 1. While more of an educational activity for this project (and described in detail in that section), our seedbank analyses of 50 farms will also be used for research. We conducted the assessment by identifying and recording emerging weed species for five months. We will soon start comparing the species composition of each farm to their soils and management history to learn which practices are associated with which weeds. We have also started to review previous research to build a table of all the relevant traits associated with each species we identified so that we can associate specific traits with specific management practices. This will likely result in practical recommendations that farmers can use to manipulate their weed seedbank.

Experiment 2. We missed the springtime window to replicate our 2023 tests of the effect of boiling water on summer annual weeds, but we will be better prepared to continue this in 2025. We will also test the effect of solarization on the 50 farms' soil samples.

Experiment 3. This spring, we initiated our second round of testing various enzymes and fungal cultures for their potential to expedite the decay of weed seeds. We are screening three proprietary enzymes and ten commercially available fungal cultures by inoculating seeds of Amaranthus retroflexus in nylon mesh bags and burying them for one year in moist field soil within plastic flats at room temperature. We will exhume the remaining seeds next spring and also test viability.

Experiment 4. Over the course of the seedbank assessment, we repotted species that we suspected of herbicide resistance including horseweed, common lambsquarters, common ragweed, all the Setaria and Amaranthus species. These plants were moved to a separate greenhouse and encouraged to grow large so we could save their seed. In 2025 we will germinate those seeds so that we can screen these populations for resistance to several different herbicides.

Education

Engagement. We designed this project to benefit farmer participants as much as possible. We will use digital and printed advertisements to outline these benefits, including the stipend, free soil test, tailored weed seedbank management recommendations. Advertisements will also explicitly state what we will need from participants – soil samples, field management history, one hour of their time to review our recommendations, and a brief evaluation.

Our aim is benefit at least 25 farmer participants with historically marginalized identities. To this end, their participation will be prioritized in an otherwise “first come, first served” process with limits of no more than 15 participants from fruit, vegetable, ornamental, or field crop commodities. We will be strategic about project advertising to maximize the diversity of participants – ideally encompassing a range in age, gender, ethnicity, farm scale, synthetic pesticide usage, and proximity to urban areas.

We will work with one cohort of participants for the project duration. Our interactions will primarily be in year-one through seedbank sample collection and then two years later to discuss seedbank reports and management recommendations. Nothing is required from the participants in the meantime, so there is minimal dropout risk. At conventional farms, we will coordinate with the farmer to sample where residual herbicides have not been applied for at least six months.

We estimate that each participant will want about one hour to discuss the results of their seedbank analysis and management recommendations with the project leader, but we can provide more time if needed determine the most feasible course of action. Participants will be encouraged to contact us if difficulties arise in depleting their seedbanks, even after the project ends.

Learning. The primary learning products will be detailed reports sent to each farmer participant. All 50 reports will include:

- An analysis of the density and composition of the weed species in their weed seedbank. Key personnel have done these so routinely (Brown and Gallandt, 2019; Mohler et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2018; Sosnoskie et al., 2006) that we do not consider them as “research” but more in line with a service that we can provide the farmers, like a soil test. See the cited papers for details, but briefly, these are conducted by spreading soil samples on flats in our greenhouse and recording emergence by species.

- A bar chart with the total weed seedbank density of each participating farm organized by commodity (with the other farms’ identifying information removed).

- Photos with key identifying characteristics of each weed species.

- A listing of all the species encountered in the project with our review of how to target “Achilles heels” in their biology. Examples provided in Previous Work.

- Tailored weed seedbank management plans that account for each farm’s unique suite of weed species, preferred crops, soil conditions, and available labor and equipment. At least two different approaches will be presented.

- Though not critical to project success, we hope to include research updates on how seedbank depletion may be expedited using soil fertility, superheating, fungal enzymes, or herbicide resistance management.

After the reports are sent to each participant, the project leader will follow up via phone or Zoom to discuss the feasibility of the management recommendations and how they may need to be adjusted based on the skills, interest, and concerns of each farmer.

The reports will be published online and in-print as well as presented at grower meetings so that other farmers, consultants, and educators may learn from the results. Whether they learn through direct participation or through our subsequent dissemination, our aim is to make farmers aware of opportunities to deplete seedbanks based on the biology of the species present.

Evaluation. Following our discussions with farmer participants about their seedbank reports, we will send an anonymous phone-based survey (via “Poll Everywhere”) with the questions in the attached Verification Tool to determine if our performance target was achieved. These surveys will also be used via projector screen questions with text message responses at the end of each of our presentations at winter grower meetings. Since all evaluations will occur at the end of the project with minimal opportunity to incorporate feedback, we will rely heavily on our project advisory committee to review our report drafts and ensure we are as impactful as possible. Furthermore, all of the farmers on the committee will also be participants, so by meeting to discuss the results of their seedbank reports in advance of the other participants, we can incorporate their feedback on the process and benefit the remaining participants.

Milestones

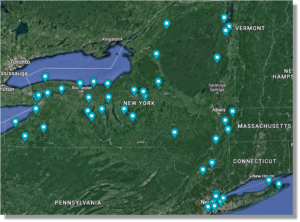

Engagement: July 1, 2023. COMPLETE. We recruited 50 farmer participants. Through our advertising, farmers learned about the project and contacted us to demonstrate their interest in improving their weed seedbank management. Advertising and initial engagement were conducted by project leader, B. Brown, urban agriculture educators, S. Anderson and L. Koenick, as well as many others in our network of Cornell, extension, farmer, and industry professionals. Over 150 farmers expressed interest, which allowed us to select 50 that best represented the breadth of the state's agriculture in terms of crops, geography, and demographics.

- NOTE: HISTORICALLY UNDERSERVED FARMERS. We are certain that we surpassed our goal that at least half of the 50 farmer participants benefiting from this project are from historically marginalized identities. To be minimally invasive and help ensure trusting relationships with our 50 participating farms, we did not formally collect demographic data. But anecdotally, many of our participating farms mentioned being of limited resources or in their first few years of establishment, several mentioned their Veteran status, and more than half of our participating farmers presented as women. Fifteen of our participating farms are urban farms. Several of our participating farms openly identify as "queer-owned." And several of our farms explicitly serve as incubator farms for historically marginalized communities or recent immigrants.

Engagement: December 1, 2023. COMPLETE. All 50 participating farmers were visited. Farmers were asked about management history of the field they selected for sampling. Seedbank and soil test samples were collected. Seedbank samples were placed in our walk-in refrigerator until the spring of 2024.

Learning: March 1, 2025. Our seedbank analysis and management recommendation reports will be completed. This milestone will be conducted by B. Brown, M. McClements, and our Extension Aide, with additional guidance from A. DiTommaso and L. Sosnoskie. We will send our drafted reports to all key personnel and project advisory committee members to ensure recommendations are as useful and as culturally appropriate as possible.

- IN PROGRESS. We have completed a full five month period of encouraging germination from the 50 soil samples. Farms ranged from only about 100 weeds emerging per square meter all the way up to nearly 30,000. There are still a few species that we repotted to let them flower so they can be accurately identified. We are also in the process of reviewing previous research on each species so that we can make the best possible management recommendations to each farmer based on the biology and "Achilles heels" of their top weed species.

Learning: June 1, 2025. We will incorporate feedback on the reports from key personnel and project advisory committee members and send all 50 completed reports to the participating farmers. Farmers will learn the density and composition of weed species in their seedbank; see how their total seedbank density compares to the other farm participants; learn key identifying characteristics from high-quality photographs of their weeds; learn about “Achilles heels” of each species that can be targeted to improve management; learn how their entire suite of weed species can be addressed with a management plan that addresses possible gaps in their previous weed control; and learn about any project research updates on methods to expedite the depletion of weed seedbanks. B. Brown, S. Anderson, and L. Koenick will send these reports to the farmers with whom they have established relationships.

Learning: February 1, 2026. B. Brown will speak with each of the 50 farmer participants to review their seedbank analyses and management recommendations. He will listen to their interests and concerns about the proposed management recommendations and discuss possible adjustments to improve their feasibility. Farmers will learn more about how to use their current equipment and resources to better target the biology of their weed species.

Learning: February 28, 2026. We will disseminate our results to the broader farming community by publishing our anonymized seedbank analysis and management recommendation reports online and in-print, and by presenting the results at winter grower meetings including the Empire State Producers Expo, NOFA-NY, Long Island Agricultural Forum, and Field Crop Congresses. This Milestone will primarily be conducted by B. Brown, but all key personnel will incorporate project results into their extension repertoire. B. Brown will publish the web and printed reports. Based on our past project successes, B. Brown will also distribute slides with project results so that other New York agricultural educators can further extend the project’s reach. Farmers reading these reports or hearing about key project results will see many examples of how other farms in situations similar to their own have adjusted their management to target the biology of key weed species.

- IN PROGRESS. Although the results are not yet complete, we have made several presentations about this project, the general importance of seedbank management, and how to tailor management based on the biology of the weed species present. We will give many more presentations once the results are complete, but this has been our activity thus far:

-

Brown, B. 9/25/23.Different Strokes for Different Folks: Weed Management Based on Species’ Biology. Horticulture Section Seminar. Cornell University. Ithaca, NY.

- Brown, B. 1/24/24. Weed Management for Small Diversified Farms and Gardens: “Achilles heels” of Weed Species. Cornell Cooperative Extension. Kingston, NY.

- Brown, B. 4/5/24. Weed ID and Why it Matters. What's Bugging You? New York State Integrated Pest Management. [virtual event].

-

Brown, B. 6/20/24. Understanding Key Differences between Weed Species. Cornell Cooperative Extension. Mead Orchards. Tivoli, NY.

- Brown, B. 8/15/24. Weed Seedbank Management in Conifers. 2024 Christmas Tree IPM Field Day. New York State Integrated Pest Management. Geneva, NY.

Evaluation: September 1, 2026. We will send automated phone-based polls to our 50 participating with three questions that will assess each farmer’s success in adopting enhanced weed seedbank management tactics and the estimated benefits for each farm. A similar evaluation will be used at the end of our presentations to poll an additional 500 farmers. This Milestone will primarily be conducted by B. Brown.

Milestone Activities and Participation Summary

Educational activities:

Participation Summary:

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

40

Participants will deplete their weed seedbanks based on the biology of the species present

1,500 acres

Weed emergence will be reduced on 1,500 acres. Starting in Year 3, this will result in a combined increase in net profit of $50,000 per year due to a combination of improved yields and reduced weed management costs.

Target #2

50

Farmers will indicate their intention to improve weed seedbank management .

2000 acres

Weed emergence will be reduced.

Additional Project Outcomes

To receive interest in this project from 150+ farmers looking to participate was very exciting. Weed management is a consistent struggle and this project offers some possible solutions based on each weed species' "Achilles heel." Clearly, we could expand this type of offering in the future and perhaps pursue other funding streams to support it.

Although the main educational component of this project will be delivered in the form of a report to each participant with their seedbank analysis and tailored management recommendations, we also answered many weed management questions in our initial visits, which hopefully allow the participants to test one or two new suggestions based on the biology of their more problematic weeds in advance of receiving our full report in another year and a half.

The 50 farmer participants are very excited to learn more about their weed seedbanks and hear possible ways to improve their weed management based on the biology of each species. Their written comments included:

“Thank you so much for this awesome news!! We’re excited to meet you and work with you!”

“Super news! We are in. Thanks so much for including us! Looking forward to learning through this project.”

“Thank you so much for selecting us to participate in this study!”

“That's great - thank you! That'll be neat.”

“Sounds great, we are excited to participate!”

“I would very interested! Sounds like a great program”

“Thank you! We’re excited for this project.”

“This is exciting news. I'm really looking forward to what the survey finds.”

“Great! Looking forward to being a part of it.”

“This is exciting news for us. We look forward to being part of your trial.”

“Awesome! I am excited to participate in this study.”

One component of this project is investigating enzymes that could degrade weed seeds. From preliminary experiments started last year, enzymes applied to weed seeds did not decrease seed viability, but instead increased seed germination rates, which maybe just as useful from a management standpoint if seeds can be encouraged to germinate prior to planting crops. This work as well as the boiling water studies will be further investigated next year. Both component studies as well as an overview of the project were presented in our recent Cornell seminar: Weed Management Based on Species' Biology (posted in Informational Products).