Progress report for LNE25-486

Project Information

Swede midge, an invasive pest of brassica crops, poses a threat to small-scale,

organic, and urban vegetable farms in the Northeast. Due to its small size and feeding

within the growing point of the plant, it is often not found and is misdiagnosed. As a

result, populations can build to devastating levels on farms. Small-scale and organic

farms are most at-risk due to lack of space for crop rotation and effective insecticide

products. Similarly, urban growers suffer large crop losses from swede midge due to

inability to move production away from infested areas. Results from our three

vegetable grower surveys have shown a desire for improved organic management

options for swede midge, with an emphasis on biological control. On urban farms

specifically, brassica crops were identified as one of the most challenging to grow, with

swede midge highlighted as a top issue limiting production of culturally-important

crops of underserved communities such as collard greens. On rural farms, Plain

growers have also expressed the need for improved swede midge management, as

this pest is a challenge for brassica producers growing for produce auctions in western

and northern New York. In Maine, where swede midge is a newer invasive pest, Plain

growers in the northern part of the state have suffered yield losses due to this pest.

With a wide range of production practices, farm landscapes, and communities, scaleand

culturally-appropriate swede midge outreach is needed to meet the needs of

organic and urban growers across the Northeast.

The outreach objective of our project is to assist organic and urban growers with

monitoring for this “invisible” pest to better understand populations on farms, and use

this information to design integrated pest management programs (IPM) using ground

barriers, crop rotation, netting, and other non-insecticidal strategies. To improve

accessibility of organic swede midge outreach materials, we will translate existing

resources to Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, and French. For Plain growers, we will work

with produce auction communities to ensure their understanding of swede midge

biology and then guide their adoption of IPM practices to improve the economic

viability of brassicas grown for their auction. Lastly, we plan to develop another

management strategy for swede midge. We will conduct a research experiment to test

whether application of New York-native persistent entomopathogenic nematodes can

suppress emergence of swede midge from the soil, resulting in crop protection. We will

partner with growers and extension educators in New York and Maine to disseminate

research results and management resource materials to growers to better manage

swede midge, resulting in increased yield of organic broccoli and other brassica

vegetables to meet the demands of consumers, improve economic viability of organic

and urban farms, and improve environmental sustainability of brassica crop

production.

Twenty-five farmers will adopt new practices to manage swedemidge (including crop rotation, insect exclusion netting, ground barriers, etc.) resulting in recovery of $1,500/acre in losses on 35 acres.

Our proposed research and outreach projects aim to improve environmentally and

economically sustainable pest management options for swede midge on organic and

urban farms, which will directly result in improved crop yields and profitability. Our work

is directly applicable to SARE’s outcome statement in that it will support farmers’ abilities

to steward the land to ensure sustainability through non-insecticidal pest management

options that consider agroecological interactions and benefits. Additionally, our project

prioritizes partnering with historically underserved communities and improving

accessibility of resources and technical support through a commitment to working in

diverse urban communities and translation of materials to multiple languages.

Growers from diverse farming communities have expressed the need for improved

organic integrated pest management strategies for swede midge, highlighting interests in

non-insecticidal strategies appropriate for small-scale farms, biological control, and

increased outreach. Our proposed project aims to work with individual farms to support

them in adoption of swede midge IPM strategies while considering farm landscape

variables, production practices, and economics. Specifically, we will focus on noninsecticidal

strategies including ground barriers, which suppress swede midge emergence

from the soil through the use of tarps or landscape fabric, which are currently used on

many farms for other production benefits. On urban farms, we will work with producers to

implement insect exclusion netting, growing non-susceptible crops, temporal crop

rotation, and other practices suitable for small growing spaces. Use of pheromone

monitoring will inform decision-making on farms with assistance from the project team,

where trapping will make this “invisible” pest visible and elucidate its population

dynamics on farms.

Our proposed research project aims to improve non-insecticidal swede midge IPM by

adding another tool for organic and urban growers, entomopathogenic nematodes.

Entomopathogenic nematodes can infect the soil-dwelling stages of swede midge by

entering the resting cocoons and pupae, killing the midges before they emerge as adults

to infest a crop. Many vegetable producers use nematodes for pest control already, yet no

research studies to our knowledge have tested specific persistent strains native to the

Northeast that are known to be highly adapted to our growing conditions. Given that

growers in our survey overwhelmingly expressed interest in biological control research,

we will test New York strains of nematodes to determine whether they can suppress

swede midge. If effective, growers will immediately have access to a commercially

available product that can be used for pest control on organic farms.

Cooperators

Research

Entomopathogenic nematodes are small roundworms that can infect and kill insects. Nematodes can infect soilborne late-stage larvae and pupae of swede midge (Evans et al. 2015), preventing emergence of adult flies that can lay their eggs on crops. Here, we propose testing the following research question through a field experiment: Will persistent NY-native entomopathogenic nematodes applied to infested soil suppress emergence of swede midge and reduce damage to a brassica crop?

2025 Research Methods:

In 2025, we conducted the first year of our experiment trialing entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN) to manage swede midge. A replicated cage study was set up at a grower cooperator’s field in Oakfield, NY in May (Fig. 1). Soil within the 4’ x 4’ cages was infested with swede midge pupae following a previous experiment at this site. Our experiment included two treatments: untreated (control) and treated (EPN) cages and 7 replications. The replicates were blocked according to previous year’s swede midge pressure, e.g. high (reps 1-3), medium (reps 4-6) and low (rep 7). We used broccoli as a test crop to determine whether swede midge damage differed between treated and untreated cages. Five broccoli c.v. Emerald Crown transplants were planted in each cage on May 15. EPNs were sourced from Persistent Biocontrol. New York-native persistent strains of Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (enough to treat 1 acre) were washed from wood chip substrate with 1 gal of water into solution. The solution was evenly divided into 7 aliquots of 541 ml, one for each replicate/cage. Then, 108 ml of EPN solution was applied to each of the 5 freshly planted broccoli plants per cage. Untreated cages received water at the same time. Each cage consisted of 2 4-ft tall stainless steel hoops that were covered with ProtekNet 25g insect exclusion netting, which was secured to the ground with rocks/stones.

Swede midge adults were monitored in each cage using Jackson traps (1 trap/cage), sticky liners were changed weekly (and midges enumerated) and pheromone lures were changed every 4 weeks. For the second broccoli planting (planted Jul 8) the cages were extended an additional 4-ft (Fig. 2) and the third planting (planted Aug 28) returned to the same 4’ x 4’ section where the first broccoli planting was (EPN-infested soil). Broccoli crowns were harvested when mature and given a swede midge damage rating from 0 – 5, where 0 = no damage, 1 – 4 reflect increasing severity of twisting, scarring, and deformity of the broccoli crown, and 5 = blind plant with no head. 1 = minor damage; 2 = minor-moderate damage, where quality or yield may be reduced, but head is still marketable; 3 = moderate damage, unmarketable; 4 = moderate-severe damage, unmarketable. Differences between crop damage ratings and total swede midge captures during the timeframe for each of the three broccoli plantings were analyzed using t-tests, and statistical significance was determined at P<0.05.

Soil sampling and waxworm bioassays were conducted at three timepoints during the experiment to determine whether the EPNs had successfully established. An initial soil sampling and bioassay before the start of the experiment was conducted on May 8 to determine whether native nematodes were already present in plots, which would interfere with our test of the commercial EPNs. Two additional bioassays were conducted on Jun 18 (34 Days After Transplanting (DAT)) and Sept 24 (132 DAT) to assess establishment of nematodes in treated cages and look for contamination of soil in untreated cages with EPNs. The May and June soil samplings were taken from the first 4’ x 4’ sections of the cages where the EPNs were applied. For the September sampling, 5 samples were taken from the first section of each cage and 5 samples were taken from the second (2nd broccoli planting, no EPN treatment) section of each cage. At each sample date, ten 4-6” x 0.75” soil cores were removed from each cage, broken apart, and placed separately in deli containers. The soil cores were taken from beneath the broccoli plants. Ten waxworms were added to each container and observed for infection by EPNs 1 week later (Fig. 3). Infection of dead waxworms was determined by color of the cadaver (tan, brown and brick red colors indicate infection) and collection of EPN specimens in a modified White trap.

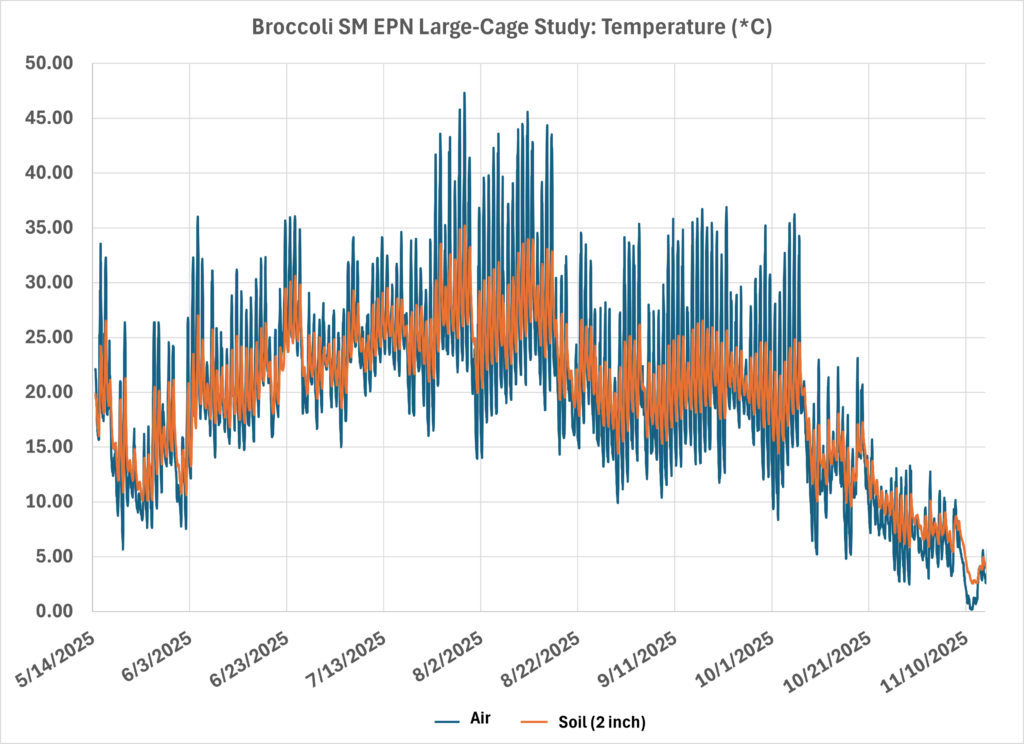

Two temperature data loggers were set up in the experiment, one in each of two cages. Each logger had two sensors, with one measuring temperature in the top 2” of the soil and the other measuring air temperature at approximately 3” above ground level. Loggers recorded temperatures hourly. Temperature data were used to better understand environmental conditions during the season and their possible impact on swede midge populations and EPN establishment.

2025 Research Results

While our waxworm bioassays confirmed that the EPNs established successfully in the treated plots (data not shown), there were no significant differences in swede midge populations or crop damage between the untreated and EPN treatments (Table 1). Persistent Biocontrol considers that if 20% or more of the soil samples per cage test positive for EPNs in the waxworm bioassay, that EPNs were effectively established. Our initial sampling (May 8) revealed no nematodes in the cages prior to treatment. On Jun 18 (34 DAT) 6 out of 7 (85.7%) of the EPN-treated cages tested positive for EPNs while EPNs were not detected in any of the untreated cages. On Sep 24/Oct 1, Heterorhabdtis bacteriophora (brick-red waxworm cadavers) was established in each of the EPN cages, while no EPNs were detected in the untreated cages. No EPNs were detected in soil samples collected from the 2nd broccoli planting, which was not treated with EPNs. Clearly, EPNs did not migrate from their original treatment site. No significant differences were observed in mean numbers of swede midge captured in cages during the duration of each of the three broccoli crops. Broccoli crop damage ratings also did not differ between treatments (Table 1). Because the EPNs were applied to the soil after swede midge pupae were already present and ready to emerge, we did not expect to observe fewer adults and less crop damage in our first planting of broccoli. Due to the hot and dry conditions of summer 2025, however, the EPNs may not have been able to move into the area of the cages where the second broccoli crop was transplanted. EPNs require soil moisture for movement. Additionally, our temperature sensors recorded very high temperatures (over 40 degrees C), which may have impacted both swede midge and EPN life cycles; very few swede midge were captured in the cages later in the season (Table 1). Lastly, clubroot disease was found in broccoli in several of the cages, reducing the plants’ growth and head formation. Stressed club-root infected broccoli plants are not desirable for swede midge to infest.

In 2026, we plan to utilize the 2025 cages for a second year of the experiment, leaving fallow cages with clubroot and only using those without the disease. These cages will allow us to observe the impact of EPNs on swede midge populations and crop damage after having established for one year. Because the swede midge population is very low in most of the cages, we are planning on two plantings of broccoli, the first of which will hopefully build up the swede midge population. We anticipate the second planting in 2026 to give us the best read on efficacy of EPNs on swede midge. Additionally, we will set up new cages at the host farm on new ground that we will infest with swede midge. Establishing new cages to use in 2027 will allow for the ground to be rotated away from brassica crops, reducing clubroot pressure. New cages prepared for 2027 experiments will be inoculated in 2026 with swede midge obtained from a University of Vermont colony.

Table 1. Mean number of swede midge caught per trap per cage and crop damage rating to broccoli in untreated and nematode-treated cages in Oakfield, NY (n = 7).

| Untreated | Treated | Statistical Significance | |

| First broccoli planting (May 15 - 23) | |||

| Number of swede midge | 191 | 198 | NS |

| Crop damage rating | 5 | 5 | NS |

| Second broccoli planting (Jul 8 - Oct 1) | |||

| Number of swede midge | 40 | 61 | NS |

| Crop damage rating | 0 | 1 | NS |

| Third broccoli planting (Aug 28 - Nov 14) | |||

| Number of swede midge | 6 | 7 | NS |

| Crop damage rating | 0 | 0 | NS |

Education

The goals of our education activities are to assist growers in better understanding

swede midge biology and populations on their farms to inform adoption of integrated

pest management practices, resulting in reduced crop loss. Farmers will be recruited

to participate in this project through our existing extension networks, listservs, and

peer-to-peer outreach through the advisory committee. Farms with ongoing

relationships with the project team through previous grants (see Previous Work) will be

invited to participate.

Objective 1: Assist vegetable growers with swede midge population

monitoring.

We will use pheromone traps to monitor swede midge as a means to “see” this almost

invisible pest and to understand how it is affected by management practices. For this

project, we are planning to work with 10 individual small-scale brassica growers over

the 3-year project period to monitor for swede midge from May through first frost for

1-2 years. On each farm, we will set up 1-4 traps within current and past brassica

fields, depending on farm size and field layouts. The traps will be monitored each week

for swede midge by the project team. In the first year, emphasis will be on relating

pest pressure to current management practices and the second year will focus on

implementing effective management strategies using our expertise and decision tree

for organic growers (see decision tree in Hodgdon et al. 2024). The project team will

track information regarding brassica crop planting and harvest dates, and key

production practices including installation of row cover or netting, and crop

termination. Swede midge damage to all brassica crops will be rated. Using our

Verification Tool, we will measure differences in yield and profitability of brassica crops

as a result of swede midge management.

Objective 2: Support urban vegetable growers with swede midge

management.

We will work with five urban farms in NYS to develop individual integrated pest

management plans to disrupt their swede midge populations. To overcome language

barriers within underserved communities, we will translate our fact sheets ‘Organic

Management of Swede Midge,’ ‘New Crop Rotation Recommendations for Swede

Midge’ (Hodgdon et al. 2017; Hoepting and Vande Brake 2020) and a new fact sheet

on using ground barriers into Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, and French to meet the needs

of New American growers in NY and ME.

Objective 3: Conduct ground barrier demonstrations on farms to suppress

swede midge emergence.

Swede midge pupates in the soil over the winter underneath infested plants and

emerges as adults in the spring. We have found that ground barriers (e.g. tarps and

landscape fabric) can successfully prevent emergence when covering ground infested

with swede midge pupae. We will assist five growers with use of ground barriers for

swede midge management, with placement informed using our trap data. Using the

farmers’ experiences, we will write a fact sheet and newsletter article detailing how to

use ground barriers effectively for swede midge management. We will also add ground

barriers to our decision tree, which will be translated to the four languages.

Objective 4: Increase awareness of swede midge amongst Plain communities.

We will work with local extension staff to offer three hands-on trainings for

auction/coop groups in NY and one in ME to improve grower understanding of swede

midge and management. Trainings will include field walks on farms in NY and ME and

auction meetings organized by auction education boards and extension. Each grower

will leave the training with a plan that they will use to manage swede midge on their

farms with the aid of our decision tree. Key members of the Plain community will guide

our outreach plans to ensure that delivery and materials used are culturally

appropriate. We will document their current brassica production practices at the

beginning of the training, and their plans for managing swede midge before they leave

the training. Then, in Year 3, we will follow up with growers to document their

implemented swede midge management practices, yield and economic recovery, and

any increases in brassica production acreage (see Verification Tool).

At 3-5 on-farm workshops or conferences per year, we will discuss swede midge

management with small, organic and urban brassica growers and 2-3 of the growers

participating in swede midge monitoring will hold field walks at their farms, where

swede midge will be discussed. We will request all growers who attend any of

educational programs fill out brief pre/post-program surveys to document progress

towards our performance target, including reduction in crop loss due to swede midge

(see Verification Tool).

Milestones

Milestone 1: Grower advisory committee meeting (Engagement)

In March-April 2025, we will hold our first project advisory meeting with the project team and committee. During the meeting, we will discuss proposed plans for the project within the first year. Feedback from our extension and grower committee members will be used to shape our plans for the following year. The committee will meet each winter of the project moving forward via Zoom.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: The advisory committee met on April 29, 2025 via Zoom. The project leaders presented an overview of the grant projects proposed and plans for research and education activities in 2025. The committee members provided feedback on the plans and asked questions to learn more about swede midge as a pest. Two members were unable to join the meeting, and the project team met with them individually afterwards to discuss 2025 plans and solicit input. The committee members were also consulted with at multiple times during the year as the project activities were conducted. The next committee meeting is planned for late January 2026.

Number Participating: 5

Milestone 2: Grower recruitment (Engagement, Evaluation)

In March-April 2025, we will recruit growers for swede midge monitoring (Obj. 1) using our existing networks and through our grower advisory committee. Five participating growers will complete an intake survey (see Verification Tool) to document farm information and gauge trapping needs. The following year, five additional growers will complete the intake form for trapping.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: We recruited seven farms to participate in our monitoring program: Journey’s End Refugee Services, Massachusetts Avenue Project, Foodlink Community Farm, 5 Loaves Farm, Bucksberry Farm, Echo Farm, and Full and By Farm. The farmers contributed information on their brassica production, swede midge losses, and other information for our intake forms.

Number participating: 7

Milestone 3: Outreach material translation and distribution (Engagement)

In April-June 2025, we will translate our organic management and crop rotation fact sheets to Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, and French. We will track downloads of the translated versions online and will hand them out at grower meetings and at farm visits, reaching 100 downloads or individuals total by November 2028.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: The fact sheets received a branding consultation by Cornell IPM, which was needed before they may be translated. The existing fact sheets will be translated in 2026.

Milestone 4: Swede midge monitoring (Engagement, Learning)

From May - October in 2025-2028, we will monitor for swede midge on 5 farms annually in NY (10 total), tracking their population and crop damage throughout the growing season. The information will be conveyed to growers to help them understand swede midge population dynamics throughout the season and inform management strategies. Five farmers will be able to identify swede midge and crop damage, and decide on appropriate management.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: In 2025, we monitored for swede midge on seven farms in NY:

Northern New York

In northern NY, traps were set up at Echo Farm (Essex), Full and By Farm (Essex), and Bucksberry Farm (Saranac) in late April/early May through late October. Traps were taken down when there were two consecutive weeks of zero midges captured. Each week, the trap counts were relayed to the farmers. Farmers learned about the population dynamics of swede midge on their farm, what the insect and damage symptoms look like, effective management strategies, and how monitoring traps work. Farmers altered their management strategies for swede midge during the season based on our trap findings.

Echo Farm

Echo Farm is a small diversified organic vegetable and livestock operation in Essex, NY. The primary market for their produce is for their catering business. In 2023, the farmers reported total brassica crop loss due to swede midge. Because of this, they did not grow any brassica vegetables in 2024, but decided to grow them again in 2025. In 2025, insect exclusion netting was used to manage swede midge, based on our recommendations. Netting was installed over their fall broccoli, and removed just prior to head formation. Netting was also set up over their fall red cabbage.

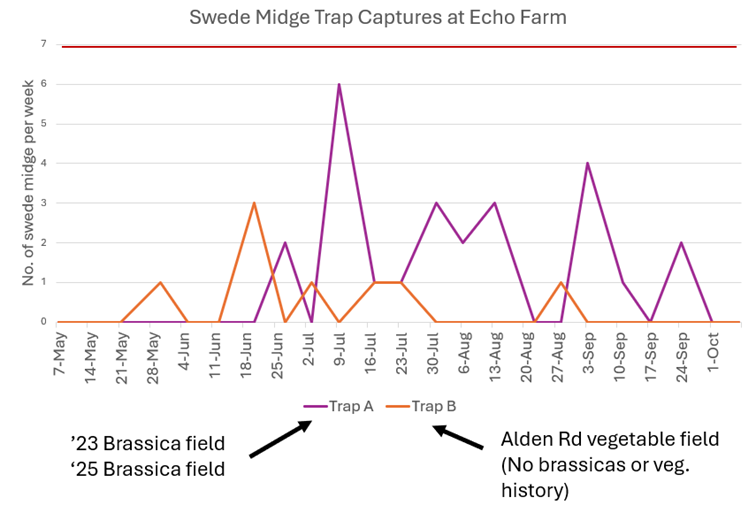

We set up two swede midge monitoring traps at Echo Farm and assessed swede midge crop damage in 2025 to assess the impact of their 2024 “brassica break” on swede midge populations. One trap was set up on the main farm within their brassica vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, and mustard greens, grown on ~0.1 acre). The second trap was set up in a field down the road (“Alden field”), approximately 1,000 ft away. Vegetable crops had never been grown in Alden field. Each trap consisted of a Jackson cardboard trap, sticky card liner, and pheromone lure. Lures were changed every four weeks and adult midges on sticky cards were counted weekly for 22 weeks by the project team.

Brassica crops were assessed for swede midge damage on Jun 20, Aug 12, Sept 11, and Oct 7 and 15. Swede midge crop damage was rated using a 0 – 3 scale, where 0 = no damage, 1 = minor leaf twisting and swollen petioles, 2 = moderate leaf twisting, puckering, and/or swollen petioles, and 3 = blind plant with no head formation or multiple shoots. In the fall, a more thorough assessment was conducted of Brussels sprouts, the major brassica crop grown on the farm. Numbers of sprouts damaged by swede midge (Fig. 5) were counted on a subsample of 25 plants twice. Other pests and diseases of the brassica crops were scouted for at each damage assessment as well (e.g. cabbage aphids, Alternaria disease) and communicated to the farmers. Trap count and crop damage findings were relayed to the farmers weekly or as needed.

Trap captures were low at Echo Farm in 2025, but traps captured midges most weeks during the growing season (Fig. 6). Swede midge trap counts never exceeded the action threshold for insecticide application of 7 males per trap per week. Surprisingly, swede midges were captured at Alden field, despite there being no infested brassica crops there previously. Swede midge use brassica weeds as hosts, and pupae may be spread between farm fields on soil attached to tillage equipment. These two phenomena are believed to be the reason why we captured swede midge at Echo Farm’s Alden field.

Crop damage remained low to moderate during the season. In our June damage assessment, broccoli and green cabbage plants showed the greatest damage from swede midge (6% and 12% damaged, respectively), with most damaged plants receiving a rating of 3. We evaluated the farm’s sprouting broccoli crop in August, and 18% of the total sprouts on the plants showed swede midge damage rendering them unmarketable by retail standards (curling and scarring within the sprouts). In our fall damage assessments, 1% or fewer of individual Brussels sprouts and broccoli crowns were damaged by swede midge. In the farm’s fall red cabbage planting, however, 11% of plants showed multiple heads (rating 3). The Echo Farm case study shows that despite forgoing all brassica crops in one year, the pest persists in low levels and can build over the season. Even so, Echo Farm experienced overall low levels of swede midge and a majority of the crop was marketable, a success when considering their 2023 losses. Considering increased crop revenue from sprouting broccoli alone, the farm harvested $29,333 more on a per acre basis (extrapolated from $88/0.003 ac increase) in 2025 compared to complete losses in 2023. Additional economic analyses are underway in 2026 for their other crops.

Full and By Farm

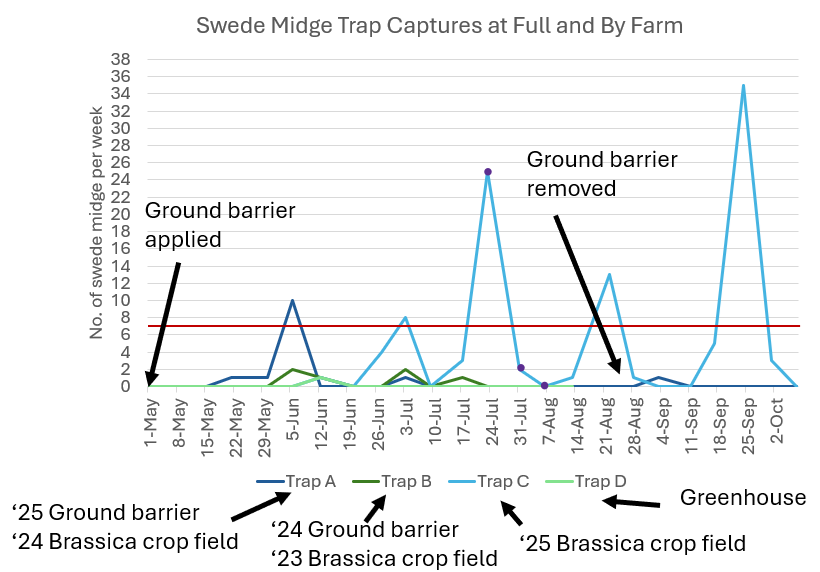

Full and By Farm is a small diversified fruit, vegetable, grain, and livestock farm in Essex, NY. The primary market for their produce is through their Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) shares, with some also sold locally at retail outlets. Similar to Echo Farm, Full and By Farm reported near complete losses of their brassica crops in 2023 (fall plantings). We began work with Full and By Farm in 2024 to assist them in managing swede midge, setting up monitoring traps and a ground barrier demonstration on their farm (see Milestone 6). In 2025, the farm grew approximately 0.13 acres of mixed brassicas, including Brussels sprouts, kale, cabbage, sprouting broccoli, cauliflower, kohlrabi, rutabaga, and mustard greens within two spring and two fall plantings. Floating row cover was used at the beginning of the season for the spring plantings until early June to exclude all brassica pests. Crop rotation away from the 2024 planting and ground barrier were used to manage swede midge in addition to the row cover, at our recommendation.

At Full and By Farm, we set up four Jackson traps for swede midge monitoring that were checked weekly for 23 weeks throughout the season, one in each of the following fields (2023 brassica field, 2024 brassica field, 2025 brassica field, and within their propagation greenhouse. Trap counts exceeded the action threshold four times during the season, with a peak of 35 midges captured in late September (Fig. 7). Frosts in late September and early October caused the trap counts to drop significantly following this peak. During three weeks of the study, an Omni bucket trap was used in place of the Jackson trap in the 2025 brassica field. The trap contained the same pheromone lure as the Jackson traps and was set up as part of a project with the University of Alberta, in addition to another Omni trap to attract a newly discovered species of midge. We found small numbers of swede midge in the farm’s propagation greenhouse during the season, which highlights the risk of young seedlings becoming infested before transplanting into the field.

Crop damage from swede midge was low throughout most of the season in most crops. We assessed crops for swede midge damage using the 0-3 point rating scale on Jun 20, Aug 28, Oct 7, and Oct 15. At least 25 plants of each crop type were assessed at each date. In October, a more thorough assessment of the Brussels sprouts crop was conducted per the protocol used at Echo Farm. 0- 3% of plants showed swede midge damage in our summer assessments. In October, 13% of White Russian kale plants received a score of 3, but yield was not impacted due to marketable leaves forming from multiple shoots on the plants. At our final Brussels sprouts data collection in October, <1% of sprouts were damaged due to swede midge.

The Full and By Farm case study shows that multiple tactics are needed on an organic farm to manage swede midge. At Full and By Farm, a combination of ground barriers, row covers, and crop rotation have reduced economic damage significantly compared to their complete losses in 2023. Full and By Farm has also begun growing more savoyed cabbages and brassica greens that are less susceptible to swede midge, which have been accepted by their CSA members. Compared to total losses in 2023, Full and By Farm harvested additional $33,150 per acre in sprouting broccoli (extrapolated from $663/0.02 ac) in 2025. An economic analysis of increased revenue from other brassicas in 2025 due to improved swede midge management compared to losses in 2023 will be completed in 2026.

Bucksberry Farm

Two Jackson traps were set up at Bucksberry Farm in Saranac, NY from May 2 through Jul 14, 2025. Bucksberry Farm produces organic vegetable and nursery crops for local farmers markets and grocery stores. One trap was placed within one of the farm’s high tunnels, where kale and broccoli crops were growing. The other was placed outdoors in a garden bed where heavily infested brassica plants were produced in 2021. No swede midge were captured in either trap, which provided the grower with confidence to expand their brassica crops next year as needed.

Urban Farms in Western NY

Foodlink Community Farm

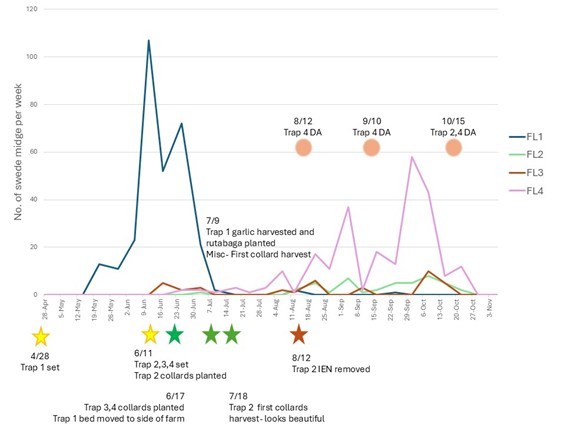

Foodlink Community Farm (FLCF) is a 2.3-acre urban agriculture campus in Northwest Rochester containing a commercial growing operation producing vegetables, fruit and honey, and a large community garden serving over 70 multigenerational New American families. We first observed swede midge damage on crops in summer 2023 and in 2024 we monitored the population and trialed a few management strategies. In 2025, the farm went under reconstruction and renovation for the early part of the season with production beds and community garden beds being moved to a new location few hundred feet away from where they were previously. The reconstructed farm has roughly 160 4’ x 12’ new raised beds built with some having some saved soil from old beds and some having new imported soil. In addition to the new raised beds, there are still a few original raised beds that are moveable with original soil in them as well. FLCF grows numerous brassicas including multiple varieties of kale, cabbage, mustards, kohlrabi and collards. We focused our damage and harvest assessments at FLCF on collards. Swede midge management strategies explored on FLCF in 2025 include delayed planting, importing new soil, and insect exclusion netting.

In 2025, we set up four swede midge traps at FLCF using the same trapping protocols as previously described for northern NY farms. Trap 1 was placed in an old, raised bed with garlic planted that had brassicas grown in it within the last 3 years and we suspected it would be a spring emergence site. Trap 1 was set up on Apr 28. Garlic was harvested on Jul 9 and then rutabaga was planted. Traps 2, 3 and 4 were set up on Jun 11. The first brassicas on the farm in 2025 growing season were planted during the week of Jun 4. Trap 2 was placed in newly built raised bed planted with collards in new soil and covered with insect exclusion netting (ProtekNet Exclusion Netting, 25 gram, 2.1 meter width) at planting. Netting was removed on Aug 12. Trap 3 was placed in a newly built raised bed planted with collards in new soil and left uncovered. Trap 4 was placed in newly built raised bed planted with collards in old soil and left uncovered. After trap set up, pheromone sticky cards were collected on weekly basis until Nov 6. Lures were replaced monthly.

Plantings were scouted weekly throughout the season for swede midge damage. Damage assessments were conducted once damage was observed on plants. No swede midge damage was observed on the farm until August 2025. Damage assessments were conducted three times on the trap 4 collards on Aug 12 (leaf rating), Sept 10 (leaf rating) and Oct 15 (leaf and plant rating). One damage assessment took place on trap 2 collards on Oct 15 (leaf and plant rating). Harvest yields were measured regularly from Jul 9 through Nov 12.

The swede midge damage assessment approach varied on urban farms depending on crop grown and the size of the planting. It’s common to see many different types and varieties of brassicas grown on urban farms including kale, cabbage, bok choi, mustards, radish, turnip, kohlrabi, collards, and more. To capture management impacts across urban farms, we focused our damage and harvest assessments on collards and kale. Leafy brassica greens are most typically what are grown on urban farms and can be harvested as ‘cut and come again’ baby greens for salad mixes, mid- or large- size for bunches. In year one of the project on urban farms, we focused on long season leafy brassica greens mainly collards and trialed two damage severity rating approaches- a leaf rating approach and a plant rating approach.

For the leaf rating approach, we assessed the five oldest leaves on 25 randomly selected plants per planting. Damage per leaf was rated on a 0-3 scale corresponding to the severity of symptoms per leaf and its marketability (0 = no damage; 1 = minor damage, marketable, some leaf puckering, twisting or swollen petioles and deformity, scarring; 2 = moderate damage, marketable but pushing it, more major symptoms as described for 1; 3 = severe damage, unmarketable, dead meristem, multiple branches, severely deformed) (Fig. 8). For the plant rating approach, we assessed 25 randomly selected plants per planting on a 0-3 scale corresponding to the severity of symptoms per plant and its marketability (0 = no damage; 1 = SM present, marketable ; 2 = half of marketable (mature) leaves are affected; 3 = over half of marketable (mature) leaves are affected).

Massachusetts Avenue Project

The Massachusetts Avenue Project (MAP) farm is made up of 13 reclaimed vacant lots, covering over an acre located on Buffalo's West Side and runs a year-round youth employment program building youth leadership skills through farming and other civic engagement programs. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs; they keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. We have observed swede midge damage at MAP for the last few years and 2025 is the first year we monitored the population. The goal of the past growing season was to monitor the population and begin forming a management plan.

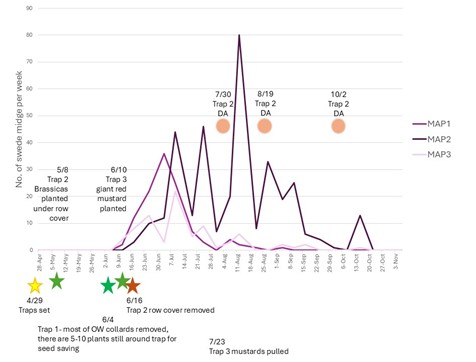

We set up 3 traps at MAP in 2025 set up on Apr 29. Traps 1 and 2 were on the main farm location and trap 3 was located a block away. Trap 1 was in the ‘front’ plot located closest to the farmhouse with collards that had overwintered and were being saved for seed. Trap 2 was located roughly 200ft away from trap 1 with greenhouse and other structures in between in the ‘shields’ plot containing 3 rows of collards for 130 plants in total, a row of kale with multiple varieties including winterbor and lacinato and a row of hon tsai tai and mustards with multiple varieties. Brassicas were planted under row cover on May 8 and row cover was removed on Jun 16. Trap 3 was located on the ‘Winter St’ plot roughly 550 ft away from Trap 1 and 750 ft away from Trap 2 with many houses and a park separating the traps. In 2025, one row of ‘Giant Red’ mustards was planted at the Trap 3 location on Jun 10 and pulled on Jul 23. After trap set up, pheromone sticky cards were collected on weekly basis until Nov 6. Lures were replaced monthly.

Plantings were scouted weekly throughout the season for swede midge damage. Damage assessments were conducted once swede midge damage was observed on plants using the protocol previously described for urban farms. No swede midge damage was observed on the farm until end of July. Damage assessments were conducted three times on the trap 2 collards on Jul 30 (leaf rating), Aug 19 (leaf and plant rating) and Oct 2 (leaf and plant rating). Harvest yields were measured regularly from Jun 23 through Oct 22.

Year 1 MAP data analysis is still in process. Preliminary year one results show that trap counts of swede midge population fluctuated by trap and management (Figure 10). The swede midge population began to rise at end of June and peaked with Trap 2 catching 80 swede midge in mid-August. We did not observe swede midge damage on mustards or lacinato kale. We did not observe damage on the overwintered collards in the Trap 1 plot. Minor damage was observed on winterbor kale and the most damage was observed on collards at the at Trap 2 location. Damage increased throughout the season on the trap 2 collards with 85% of plants showing swede midge symptoms on Jul 30 with the average leaf damage as 0.456 and 100% of plants showing swede midge symptoms on Oct 2 with the average leaf damage of 0.584. The average plant damage rating on Oct 2 was 1.44. In addition to swede midge, there was imported cabbageworm and flea beetle pressure early in the season and cabbage aphid pressure at the end of the season. The trap 2 collards produced 60 lb for market for the season.

5 Loaves Farm

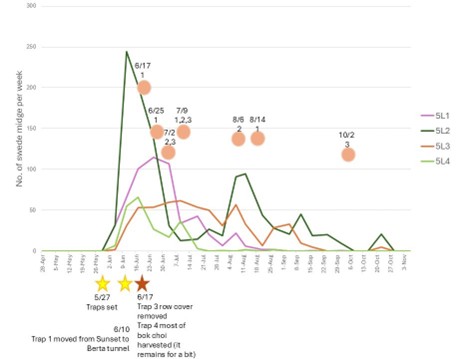

5 Loaves Urban Farm has roughly ½ acre in production and grows on four separate lots on the West Side of Buffalo. They grow a diversity of vegetables, fruits, and herbs; keep chickens and bees; and create numerous value-added products. There are 4 “fields” at 5 Loaves- West, Hill, Dewitt, and Helen. West and Hill are across the street from each other. Dewitt is a block away, and Helen is another block away. They grow all year round, grow brassica greens in the winter in tunnels in the west field. In previous years, they noticed worst swede midge damage in cabbage and broccoli and decided to not grow either in 2025. They would consider growing spring broccoli again with a swede midge management plan in place. We have observed swede midge damage at 5 Loaves for the last few years and 2025 is the first year we monitored the population throughout the entire growing season. The goal of this season was to monitor the population and begin forming a management plan.

We set up 4 traps at 5 Loaves on May 27. Trap 1 was located in the West field started in the sunset high tunnel in a left over winter kale planting and moved to the Berta high tunnel in a kale planting on Jun 10. Trap 2 was located in the Hill field planted with a four-bed rotation for salad mix with baby greens including red Russian kale, arugula, and red mustard. Trap 3 was located in the Dewitt Field in a white Russian and winterbor kale planting. Trap 4 was located in the Helen field in a covered bok choi planting that last year had broccoli and cabbage planted in it. Most of the bok choi from this trap was pulled by Jun 17 and peppers were planted. After trap set up, pheromone sticky cards were collected on weekly basis until Nov 6. Lures were replaced monthly.

Plantings were scouted weekly throughout the season for swede midge damage. Damage assessments were conducted once damage was observed on plants. Trap 1 had 4 damage assessments (all leaf ratings) on Jun 17, 25, Jul 9, and Aug 14. Trap 3 had 3 damage assessments on Jul 2 (leaf rating), Jul 9 (leaf rating), and Oct 2 (leaf and plant rating).

Year 1 5 Loaves data analysis is still in process. Preliminary year one results show highest trap catches in trap 2 with the population peaking in early June with a count of 244 and another peak in early August with a count of 95 (Fig. 11).

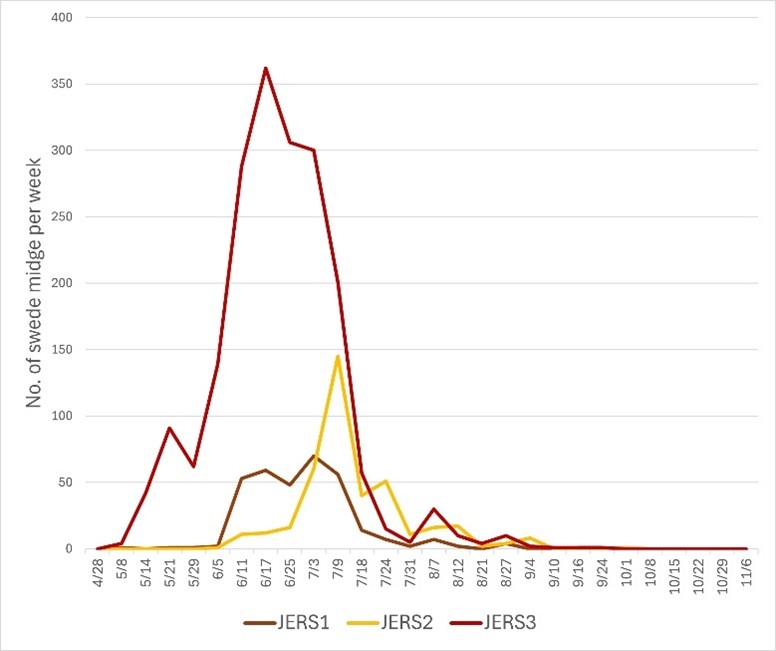

Brewster St Farm @ Journey’s End Refugee Services

The Brewster Street Farm with Journey's End Refugee Services (JERS) offers the Green Shoots for New Americans Program which facilitates urban farming opportunities on Buffalo’s East Side. The farm grows numerous culturally important vegetables from farmer participants immigrating from Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and more. Project team members have observed swede midge damage at the farm for the past several years in the greenhouse and outside fields. There are two “fields” located on the same street with two houses that separate them. Field 1 has a greenhouse (heated high tunnel) and outside raised beds, and Field 2 has raised beds. On Apr 29, three traps were set up at JERS. Trap 1 was set up in Field 1 in a bed that had collards with swede midge damage symptoms last year and this year was planted with potatoes. Trap 2 was set in Field 2 in a raised bed that had many types of kale planted. Trap 3 was located in the greenhouse next to overwintered kale in a radish planting with mizuna nearby. After trap set up, pheromone sticky cards were collected on weekly basis until Oct 8 (Fig. 12). Lures were replaced monthly. The JERS farm manager left in early June 2025 and a part time farm manager started later in the season. Due to the change in management, farm management practices were in flux for most of the season and we did not do damage assessments. We continued the traps till the end of the season for baseline data on swede midge populations on urban farms.

Milestone 5: Field meetings and outreach on urban and Plain farms (Engagement, Learning, Evaluation)

In each of 2025-2028, we will hold field walks on one urban and one Plain grower's farms, where a total of 40 vegetable growers and ag service providers will attend. Advisory committee members will be directly involved in planning program content. 25 farmer participants will complete a survey that measures their learning of swede midge biology and integrated pest management during the program, and reports their current concern for swede midge and losses experienced (see Verification Tool).

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: In 2025, we hosted seven workshops for vegetable producers in NY where swede midge and pest management were topics of discussion.

- A day-long Garlic and Brassica Workshop was held in Essex, NY on Mar 4, 2025, and the workshop was held again in Canton, NY on Mar 11, 2025. Both Plain and urban growers attended the workshops. Swede midge biology, identification, crop damage, and management strategies were covered. A farmer-to-farmer discussion followed the presentation and allowed participants to ask questions about the pest and its management. A survey was implemented before and after the program to measure learning outcomes. 37 farmers participated in total for the two workshops, and 10 completed pre- and post-program surveys to measure knowledge gain on swede midge identification and crop damage, and plans to try a new management strategy for swede midge in 2025. We measured a knowledge gain of 4 participants being able to identify swede midge and 3 reported being able to identify crop damage, and 5 planned to use a new management strategy for swede midge in 2025.

- On May 27, a Pest Management Workshop with Green Shoots for New Americans Farmer Training Program at Journey’s End Refugee Services was held for 1 hr and included 12 urban farmer participants. We reviewed cultural practices for pest management such as crop rotation, trapping to monitor pest population, showed swede midge traps and shared the swede midge life cycle and crop symptoms and explained how trap counts help us make management decisions.

- On Jul 23, 30, and Aug 6 we held Massachusetts Avenue Project teen integrated pest management workshops. Each workshop was 2 hours for a total of 6 hours of programming reaching 30 participants. We discussed types of pests and management strategies using swede midge as an example of how taking a multipronged approach is important (crop rotation, brassica variety and crop selection, traps to monitor the population, regular scouting), did a group damage assessment comparing swede midge damage on collards, winterbor kale and lacinato kale, and saw swede midge larvae with teens on July 30. We evaluated impact quantitatively through pre- and post- participant surveys. Survey queries were written on poster board, participants were handed stickers to mark their response anonymously “yes”, “maybe”, and “no” to a series of statements. After participating in the workshop, there was a 155% increase of participants reporting yes “I can identify a few types of pests on the farm”; a 41% increase of participants reporting yes “I can describe a few ways farmers manage pests”; a 113% increase of participants reporting yes “I understand what a plant family is”; and a 11% increase of participants reporting yes “I can describe the benefits of crop rotation.”

- On Jul 24, we led a field walk with farm interns at the urban farm at Camp Treetops in Lake Placid. 8 interns and staff farmers participated. We scouted for swede midge damage and discussed the insect’s life cycle, biology, and management strategies. The group reported learning to recognize damage symptoms in kohlrabi and other lesser grown brassica crops, and what swede midge looks like using a preserved specimen brought to the farm.

- On Aug 6, we held a training with the 5 Loaves Farm crew with 4 participants where the swede midge life cycle, crop damage, and trapping were discussed.

Number participating: 91

Milestone 6: Implementation of ground barriers on farms (Engagement, Learning, Evaluation)

In 2025-2028, we will assist five growers with use of ground barriers to suppress swede midge emergence using their input and trap data (Milestone 4/Obj. 1). 20 growers and ag service providers will hear the grower host's perspectives on using ground barriers for swede midge management at one field meeting. Yield recovery and grower knowledge gain will be documented at each hosting farm (see Verification Tool) in October at the end of the season.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: In 2025, Full and By Farm in Essex, NY hosted a ground barrier demonstration. Landscape fabric was used to cover approximately 225 row feet (2 beds and adjacent row middles, 6 ft across; Fig. 13) where brassica crops had been infested the previous year. In 2024, the beds contained kale and Brussels sprouts that had the highest numbers of damaged plants of all the farm’s brassica crops. The landscape fabric was installed on May 1, and removed on Aug 22. Three traps to catch swede midge adults emerging from the covered beds were set up on May 30 and remained for the duration of the demonstration. Each emergence trap consisted of a Jackson trap with pheromone lure and sticky card that hung from the top of a laundry basket, set atop a hole cut from the landscape fabric. Fine insect exclusion netting covered the holes in the laundry basket to prevent midges from escaping. The sticky cards were checked weekly and replaced as needed. Two consecutive weeks of zero trap captures determined the landscape removal date. The sum of midges captured each week from the three traps ranged from 0 to 9, with the highest counts in early June. Our emergence traps allowed us to measure what would have emerged from the bed if the fabric was not in place. Each week, the grower was provided with the emergence trap data and how to use it to inform ground barrier removal. Three other Jackson traps were set up within Full and By Farm fields to capture adults elsewhere on the farm throughout the season (see Milestone 4). Because Full and By used ground barriers for swede midge in 2024 as well, the grower now better understands the benefits and costs of using this practice to manage swede midge. Crop damage at Full and By Farm was consistently low during the 2025 growing season due to their use of multiple swede midge management tactics, and never exceeded 8% plants damaged.

Number participating: 1

Milestone 7: Creation of soilborne swede midge management fact sheet with translation (Engagement)

In 2027-2028, we will work with the five ground barrier farmer hosts to create one fact sheet on the use of the barriers for swede midge management, in addition to management of swede midge using nematodes. The fact sheet will be translated into each of the four identified languages beneficial to New American communities in NY and ME (Milestone 3). The fact sheet will be downloaded or distributed directly at least 50 times before November 2028.

Status: Not begun

Milestone 8: Evaluate increase in crop yield and yield recovery due to outreach (Engagement, Evaluation)

Using contact information with participant consent from our program intake surveys (see Verification Tool), we will reach out to our farm hosts and program participants with a post-survey and/or verbal interviews (as appropriate) to measure our performance target, including adoption of swede midge integrated pest management practices, yield and economic recovery, and increased brassica crop acreage by November 2028. Results will be included in our project final report.

Status: In Progress

Accomplishments: In 2025, we gathered information on current farm losses due to swede midge. Intake forms were completed for each farm participating in our monitoring and ground barrier programs, and contacts with other regional growers were made at programs. In 2026, we will continue working on our economic analyses (see Milestone 4 for preliminary estimates of increased revenue), comparing 2026 yields to those from 2025 and earlier.

Number participating: 10

Milestone activities and participation summary

Educational activities:

Participation summary:

Learning Outcomes

Performance Target Outcomes

Target #1

Additional Project Outcomes

Because SARE supported our weekly farm visits to check swede midge traps, we were able to include monitoring for a new midge species, canola flower midge, at two of the farms during three weeks of the 2025 season. We formed a new collaboration with two researchers at the University of Alberta in Canada, who provided us with the Omni traps to catch canola flower midge. We did catch the new midge species, and our findings represent the first documentation of canola flower midge in New York State. We also sent the researchers samples of swede midge that they will use for a population genetics study, which may result in new information about this invasive species.