Final report for LS17-278

Project Information

Interest in eastern oyster aquaculture in Georgia continues to increase, but gear performance is limited. Growers have been interested in expanding into oyster aquaculture to diversify wild oyster harvest for more than a decade. In 2014 the University of Georgia Shellfish Research Laboratory (SRL) established an oyster hatchery to provide oyster seed for research and for commercial use. To evaluated oyster aquaculture a multi-disciplinary approach was taken to evaluate oyster growth on intertidal leases, develop an oyster enterprise budget, evaluate the demand for oyster by restaurants, and work with growers on direct shipment. Covid-19 impacted restaurant and grower surveys. Since intertidal leases vary in size and conditions we examined oyster growth in tubes and found that oysters reached 62.3 mm (+1.03 SE) and 66.9 mm (+1.36 SE) within 18 months from spawn and that survival ranged from 64.5% to 70.6%. Enterprise budget estimated that for every 250,000 in oyster sales would provide $177,000 of economic impact and that farms would reach profitability in three to five years. A survey of restaurants in five cities, Savannah, Athens, Atlanta, Macon and Augusta found strong demand for Georgia grown oysters and that demand is higher than supply and favorable to direct shipping. Direct shipment of oysters by growers found that shipment is an efficient way to send small batches of oysters inland. Overnight shipment in Styrafoam coolers performed best and receiving temperature of oysters was correlated with outside air temperature (R2=0.6894). This data indicates that oyster aquaculture on intertidal leases is possible and that there is a market for Georgia oysters throughout the state. With recent changes to the Georgia Code regulating shellfish aquaculture, that took effect in 2020, we are optimistic that there will be growth of the oyster aquaculture in Georgia.

Background and Objectives

The world population is estimated to exceed nine billion people by the middle of the 21st century and growth in aquaculture production is an important component to meet the growing demand for food. Aquaculture production continues to increase and is projected to exceed wild capture production by 2030 (FAO 2018). From 2000 through 2016, aquaculture production increased from 32.4 million tons to 80.3 million tons while wild capture production has decreased slightly (from 93.5 to 90.9 million tons) over the same period (FAO 2018). In 2016, consumption of seafood in the U.S. was 16 pounds per person with 5.8 pounds estimated to be from shellfish; oyster production reached 36.6 million pounds with a value of $192 million during the same period (NMFS 2020).

The eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) is an important aquaculture species and demand for them has increased steadily. Over the past decade, commercial oyster harvest along Atlantic coast states has increased from 2.8 million pounds in 2008 to 6.8 million pounds in 2017 with an increase in value from $24.1 million to $111.0 million (NOAA 2020). Over the same time period, Georgia has seen a minimal increase in harvest from 15,496 to 28,755 pounds and value of $65,775 to $178,133. This lags behind other south Atlantic states such as North Carolina and South Carolina that have stable harvest from aquaculture and harvested 318,602 and 326,833 pounds with a value of 5.58 million and 2.61 million in 2017, respectively (NOAA 2020).

The low harvest rate in Georgia’s oyster industry is because it is built upon the manual harvest of wild oysters, which is labor intensive because of how the oysters grow. Wild oysters are crowded on dense reefs in the intertidal zone, which makes growing a naturally consistent shape, developing a deep cup, and separating oysters from one another difficult. Although wild-produced cluster oysters are perfect for oyster roasts, they are less valuable than farmed oysters grown in aquaculture operations, which use hatchery-produced seed. Farmed oysters grow with a consistent appearance that is desired by restaurants and oyster bars and command a higher price (Bliss and Walker 2012). The wild-caught oyster industry in Georgia is unequipped to compete commercially and would benefit financially by utilizing oyster aquaculture gear to become a viable industry. Georgia’s moderate climate, tidal conditions, salt marsh productivity, and abundance of phytoplankton are ideal conditions for oyster growth.

Starting March 2020, two types of shellfish leases are available within Georgia, intertidal water bottom and sub-tidal water bottom. The benefits from farming with floating gear in water column are well known, but leases within Georgia are dominated by intertidal leases that cover approximately 150,000 acres which only allow use of bottom gear. Farming oysters to harvest size in bottom cages is challenging, and the risk of fouling (Moroney and Walker 1999) or suffocation by shifting sediments (Adams et al. 1994) are concerns that must be addressed.

In addition to environmental concerns with oyster harvest, distribution of market-size oysters to restaurants by growers can be difficult. Chefs with individually managed mid to high-end restaurants (IMMHERs) in urban Atlanta and Athens are enthusiastic about and eager to obtain fresh Georgia oysters (Yandle and Tookes 2016). Distribution of oysters is challenging, as logistics companies typically deal in larger volumes of product than small growers are able to produce, and oysters are a seasonal product in Georgia. There is also interest in oysters from 90% of Georgia seafood consumers purchasing Georgia seafood at local farmers markets, but Georgia seafood is often overlooked and under represented at farmers markets (Tookes et al. 2018). Within Georgia, lease holders that obtain a Master Harvester Permit (MHP) are allowed to sell oysters directly to end users.

In 2017, it was estimated $69.6 billion of dollars spent on seafood occurred in restaurants (Love et al. 2020). With the onset of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2020, the economy of the US and the world shifted. It is estimated that 17% of all restaurants in the U.S. have closed (National Restaurant Association, 2020). Since the outbreak, there has been 65% reduction in seafood demand within the U.S (White et al. 2020). This led to an extension being granted to allow restaurant surveys in the five urban areas to capture some of the impact to IMMHERs in Georgia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this project focused on four key objectives to oyster farming in Georgia: 1) evaluate use of on-bottom growing techniques for oyster growth and survival to harvestable size on intertidal leases, 2) survey IMMHERs in five urban areas within Georgia, 3) evaluate the feasibility of direct-to-end user distribution methods via ground and overnight shipping, and 4) develop a budget tool to determine if on-bottom oyster farming will be economically viable and profitable.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Oyster Growth

Permitting

When this grant was submitted, use of gear on intertidal leases had been allowed by growers as long as the gear used did not exceed 0.61 m (2.0 ft) off bottom, the height of a crab trap. In fall 2017, supplies were ordered and gear was prepared to be deployed in summer 2018 with seed from the spring spawn from the hatchery. In winter 2018, we were informed by the state of Georgia that permits would be required prior to placing gear on the commercial leases. In March 2018, permits were submitted to state of Georgia (Appendix I) to place the cylinder cages on three commercial leases and in the waters adjacent to the Shellfish Research Laboratory. Additionally, a pre-construction notice (PCN) under the Nationwide 48 that covers Shellfish Mariculture Activities was also completed for the US Army Corps of Engineers. After review, in July 2018 the state of Georgia notified us that the permits were not approved and stated that research on shellfish could not be conducted on commercial leases. In response, the state recommended that we apply for a research and training area in the Skidway River that we could place the gear in and have the growers travel to our location to utilize the gear. A permit was filed with state in August 2018 (Appendix II) and a PCN was completed and submitted to the US Army Corps of Engineers (Appendix III). In September 2019 the state of Georgia approved the permit and issued a revocable license (Appendix IV) which then allowed the permit to move forward to be reviewed by the Army Corps of Engineers. Last communication with the Army Corps of Engineers in January 2021 indicated that the training area permit was still working its way through review.

During this time frame, the state of Georgia went through the process of rewriting the Shellfish section of Title 27 of the Georgia Code. Within the code, language was added to clearly give the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Coastal Resources Division the ability to permit the use of gear for mariculture activities on commercial lease through application for a shellfish mariculture permit (SMP). The change in code was passed in 2019 legislative session, but did not take effect until March 2020.

Methods

Work with shellfish growers is extremely important and from the onset three growers, who held intertidal shellfish leases, agreed to work with us to evaluate the use of growing oysters in bottom gear and shipping of oysters. Work with intertidal bottom cages (Bliss et al. 2016) had previously been evaluated, but there were concern by growers that the cages were too bulky and that they could only be tended at low tide. To address this concern, we evaluated the use of cylinder oyster tubes which have been demonstrated to be an effective method to grow Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) in France (Robert et al. 1993) and rock oysters (Saccostrea commercialis) in Australia (Holliday 1991).

Oyster tubes were constructed using 12.7 mm and 25.4 mm Aquamesh® (Riverdale Mills) and were 1 meter long with a diameter of 30.4 cm and a round black hard plastic float 81 cm with 8.1 cm diameter (Go Deep GD-OF-04-S) was strapped inside each tube. Stings of four tubes were to be place in the upper intertidal zone and three strings in the lower intertidal zone. Oysters from the hatchery were spawned in May 2018 and seed were held at the hatchery in floating upwelling system (FLUPSY) until they were retained on 2 mm screen (2.8 mm). Seed would then be held in 2mm mesh bags on racks at each site until they were retained on 12.7mm and were transferred to tubes.

In light of the permit difficulties, cylinder cages were hung off the two docks (Priest Landing and Skidaway Campus) owned by the University of Georgia to evaluate growth and survival. The Priest Landing dock is located on the Wilmington River and the Skidaway dock is located on the Skidaway River (Figure 1). Both locations have semi-diurnal tides of 2-3 m and water salinity between 10ppt – 34ppt and temperature range from 8.5°C - 29.9°C. The Priest Landing site is more energetic since due to its close proximity to Wassaw Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. Due to COVID restrictions, we were unable to engage growers as anticipated in the process while cylinders were hanging off the dock. Oyster spat were set out in March 2020 at 24.7mm. Seed were spawned in summer 2019 and held at the Shellfish Lab in the FLUPSY until deployment. Twelve cages (Figure 2) were hung at the surface and 12 rested on the bottom in 3 blocks with 4 cages each (Figure 3). Each cylinder was stocked at a density of 100 oysters per cage. Due to the changes in methodology, it was not possible to get estimates on how long it takes to handle the gear in the intertidal zone. We did monitor the time to pull the tubes up onto the dock and to clean them.

Figure 1. Location of Skidaway Dock (yellow) in the Skidaway River and Priest Landing Dock (red) in the Wilmington River were tube cages were placed. Chatham County, GA 2021.

Figure 2. Image of oyster tubes in the intertidal zone. Chatham County, GA

Figure 3. Image of oyster tube deployment for oyster growth study. Chatham County, GA.

Shipping

To estimate the viability of direct shipping of oyster, we examined the cost of the packaging materials, number of oysters, and shipping cost to transport oyster overnight and next day. In addition, we evaluated the feasibility of recyclable cooler containers to address concerns from restaurants to minimize shipping container waste.

Methods

Oyster processing

Oysters from cylinder tubes could not be used as anticipated, so single oysters from concurrent aquaculture research were utilized for shipping. Oyster were collected following state harvest regulations, placed in walk-in cooler that was maintained at 4.4°C (40°F) for a minimum of 24 hours at the grower’s facility or in the cooler at the Shellfish Research Laboratory (SRL). Oysters were then packed with grower assistance at their facility or at the SRL. Prior to shipping, the temperature of oysters was checked with a handheld laser thermometer (SPER Scientific Model #800103). That was calibrated following guidelines established by the manufacturer. Oyster were then packed into a either a Styrofoam (ULINE S-16478) or recyclable cooler, cold packs added, and a shellstock TTI (Time Temperature Indicator) by Vitsab® was activated and applied to the inside of the cooler. The cooler was then dropped off for shipment via next day air or ground. Instead of arranging pick-up for overnight, it was more effective to drop coolers off at the FedEx facility at the Savannah Hilton Head International Airport. In conversations with FedEx personnel, the deadline to drop a package off was 5pm. After 5pm, the price to send overnight packages increased and the earliest that ground packages would ship out would be the following afternoon. Upon delivery of the package, we recorded the outside ambient temperature, condition of the box, and the temperature of nine oysters, three from the top, three from the middle, and three from the bottom. These temperatures were averaged to determine overall oyster temperature, and status of TTIs was recorded (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Images of Vitstab shellstock TTI. 9a image show tag prior to activation (top) and after activation (bottom). 9b shows tag indicating product remained at a safe temperature (top) and that temperature is at unsafe levels (bottom).

Temperature analysis

To determine if oysters were received at a safe temperature, the average of nine oysters was used. Regression analysis was then used to plot the receiving temperature of oysters against the ambient outside temperature when received to see if there was a relationship between receiving temperature and oyster temperature. All analyses were conducted using NCSS 9 (Hintze 2013).

Business model

Enterprise budget

To assist growers with potential cost and revenue, an enterprise budget was developed within Excel software so that it could be easily used by individuals. Team members attended the Oyster South Symposium in Wilmington NC in February 2020. Oyster South Symposium is an industry group that works to promote oyster aquaculture throughout the southern region from North Carolina through Texas and holds a symposium annually that is well attended by oyster growers and aquaculture extension agents. Alabama and Virginia growers were chosen since Virginia has an established aquaculture industry and Alabama is still developing. With the 2020 symposium held in Wilmington, NC it was well attended by growers from Virginia as well as growers from Alabama. This allowed team members to make connections with growers and discuss economic items to consider when developing the budget. The information collected at the conference inferred items to consider when developing the enterprise budget.

The budget allows the individual to estimate the number of tubes they want to start with, number of tubes they plan on adding each year for the additional four years, add in oyster mortality rate, and stocking density. Tubes built for the project were manufactured at the lab and cost about $10.00 in supplies and took about two hours to assemble, which gives a total cost of $25.00 per tube (when estimated at federal minimum wage of $7.50/hour). Tubes are now also commercially available and cost $30.00 each. (For the enterprise budget the commercial price was utilized.) The budget then automatically adjusts and estimates annual expenses, estimated net revenue, and year-to-date profit and loss. In addition, to developing a budget for tube, an enterprise budget for bottom cages was also created. This will allow growers two models to evaluate the potential cost and potential profitability for the two methods that we have data for to grow oysters in the intertidal zone in Georgia.

Economic Impact

Economic impact analysis provides a method to quantify the direct economic effects of a business operation as well as the ripple effects of the financial transactions made by the enterprise for input purchases and household purchases by owners and employees of both the direct and indirect business employees.

Methodology

This approach demonstrates the role of a project or industry in the economy through a multiplier effect that begins with input expenditures stimulating business to business spending, personal income, and employment. We employ the IMPLAN input-output (I-O) model (see implan.com and disclaimer below) that separates the economy into 546 industrial sectors such as agriculture, construction, manufacturing, trade, and services and calculates the economic impact? expressed in terms of direct and indirect and induced effects. The following definitions provide insight into the metrics[1]:

Direct effects

The set of economic activity applied to the I-O multipliers for impact analysis. It is one or more production changes or expenditures made by producers/consumers as a result of an activity or policy and can be positive or negative. In this case, it is the sales/revenue of the oyster operations and corresponding jobs. Applying these initial changes to the multipliers in IMPLAN will then display how the region will respond economically to these initial changes.

Indirect effects

The resulting effects from business to business purchases in the supply chain. For the oyster enterprise, this would be purchase of any inputs or supplies needed for the business.

Induced effects

The induced effects stem from the household spending of earnings from employments, minus taxes, savings and commuter income. Examples of this might include groceries, gas, insurance, or utilities.

Jobs calculated within an IMPLAN industrial sector are not limited to whole numbers, and fractional amounts represent additional hours worked without an additional employee. With no measure of hours involved in employment impacts, IMPLAN summations for industrial sectors which include fractional employment represent both jobs and job equivalents. Since employment may result from some employees working additional hours in existing jobs, instead of terming indirect employment impacts as “creating” jobs, a more accurate term is “involving” jobs or job equivalents. It is also important to note that this type of analysis does not include cost/benefit analysis, net economic benefit, or social benefits resulting from the project. Labor income reflects the combined cost of total payroll paid to employees and payments received by self-employed individual or unincorporated business owners. Value added is the contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (or equivalent) in the region, while Output is the total production value of an enterprise, sales or revenues.

In-state Market Surveys

Each of the social science components of this project were tremendously impacted by the 2020-2021 COVID global pandemic and subsequent months of irregular life. The originally proposed methodology and data collection efforts, which were nearly complete in several cities, became completely inaccurate in the aftermath of the decimation of the restaurant industry in Georgia. In response, Yandle and Tookes created a revised methodology that would rely on in-depth, qualitative interviews to elicit restaurant experience with and potential interest in Georgia oysters, to supplement/replace the suddenly inaccurate survey data that had been collected to that point. This report reflects this temporal reality: Several project objectives have been separated into “Pre-COVID” and “Post-COVID” sections, to illustrate the original research methodology and early work, and then the revised research methodology and data collected and analyzed.

Pre-COVID

Prior to the spring of 2020, there were several attempts to create innovation solutions to shipping seafood in the United States. Businesses around the country began to connect local seafood consumers to local fishermen by providing healthy and safe methods to transport seafood directly to consumers. Our case study research highlighted Fishline, Craig Krasberg, Mike Washburn, and the Dimin Family as entities who had raised awareness for local fishermen and their respective industries. Fishline is a free app that was created in 2012 to connect local consumers to local fishermen in order to promote eating locally. They promoted the consumption of local rather than imported seafood with the hope of creating a sustainable future for the industry. Similarly, Craig Krasberg of Juneau, Alaska devised a marketing plan that connected local harvesters of crab, salmon, and halibut to consumers via direct shipments of seafood using reusable packaging materials. Kasberg’s facility, Alaska Seafood Source, provides the opportunity for these local harvesters to help create a sustainable future for the seafood industry in Alaska. Mike Washburn started his company in hopes that by directly marketing fresh seafood directly to consumers, there would be benefits such as economic advancement for fishermen, quality seafood for customers, and educational opportunities for consumers about the seafood they are purchasing. The Dimin Family created their company, Sea to Table, to make sustainably caught seafood easily available to consumers. Sea to Table works with organizations that care about the health of the oceans and the safety of the seafood they distribute. These companies all want to create a direct line of communication from fishermen to consumer in hopes of eliminating the middleman and creating a sustainable future for local fishermen for years to come. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, these entities used direct shipping methods to create relationships between producers and consumers, with the goal of promote local seafood for a better future for the fishing communities providing the food.

Post-COVID

The final phase of this research project took place during the economic turbulence of the COVID epidemic. A foundational component of this project was marketing cultured oysters to Georgia restaurants that focused on local and regional foods. As that market shut down, a series of reflections published by the editor of Seafood News (John Sackton) provided a unique opportunity to observe the disruptions the changes in the restaurant industry caused to the seafood industry as a case study. Table 2 summarized these reflections during 2020 as COVID impacts unfolded. Key insights to this study include:

- The restaurant industry took a massive hit in 2020, however, it was not quite as dire as initially predicted.

- Seafood broadly (and oysters in particular) are particularly vulnerable to foodservice industry instability.

- Safety issues, low margin, and the high cost of shipping (which consumers are unwilling to pay for) makes direct-to-consumer marketing unattractive. This is likely particularly true for oysters.

- Uncertainty about the future direction of the restaurant industry will remain for years.

While the worst predictions did not materialize, this experience is a reminder of the fragility of relying on one sector (e.g., foodservice) for a customer base, and thus the importance of diversifying. However, the unique nature of oysters (live product, requiring specific handing procedures for safety) makes entering some of the alternative markets (such as direct-to consumer) challenging (Table 2).

Table 2. Documenting Changes in Seafood/Restaurant Industry due to COVID during 2020. (Source: Seafood News “Winding Glass” Columns , Author: John Sackton)

|

Date |

Key Development |

|

March 31, 2020 |

Primarily focused on lobster and crab, but more general industry warnings; “We need to prepare for depression level economic disruption, something not seen in our lifetimes. The Federal reserve in St. Louis released a study from their economists that said as many as 47 million Americans could be laid off as of the end of June. This would correspond to an unemployment rate of 32%, higher than the depths of the great depression in the 1930’s … With this type of shock, we will see a collapse in demand for high priced items as people stretch their food budgets.” |

|

April 7, 2020 |

Restaurant closures and seafood supply chain dominant concern. “there will be no snapback in foodservice sales this summer, but instead a long adjustment period that may bring us to a totally new paradigm of seafood distribution…Two thirds of the value of seafood sold in the U.S. is consumed outside the home. If we are likely to see a long period where Americans are fearful to eat out, it will not be possible to keep the structure of the foodservice industry intact.” |

|

April 14, 2020 |

“This week, uncertainty is mounting in practically every direction. However, it is increasingly clear that areas with divided leadership or weak and uncertain crisis management are suffering more. “ Warnings of long-term supply chain uncertainty that could lead to extreme uncertainty in pricing, and availability of product. Worker safety precautions (e.g., quarantine for temp workers in AK) complicate food productions. In the face of increased costs and uncertain markets producers may just shut down. |

|

May 19, 2020 |

Discussion of degree of restaurant impact and how any improvement will be a long slog. Of note to Georgia oysters (which are aimed at the on-site restaurant market) “Independent restaurants are still hurting mightily. According to Open Table data, reservations and walk-ins are down 94% nationally than from where they were last year compared on a day by day. Even in the areas where restaurants are opening, such as Florida, Georgia, Texas and South Carolina, the average traffic in Open Table restaurants is down 81% from where it was a year ago, and it is only increasing very slowly. Georgia for example saw a 96% reduction as of May 1st, but as of yesterday, has only gone up to an 89% reduction.” |

|

August 12, 2021 |

Prediction that things will not go back to where they were, even with 2021 vaccination. “We have to confront that we are in a new world, and there is likely going to be a multi-year period of adjustment.” “In real terms it means that the fine dining segment will spend $1.3 billion less; casual dining will spend $17.1 billion less, hotel and lodging $8 billion less, and college dining $4.3 billion less. In total spending on purchases of supplies and services across all segments will drop from $206.8 billion estimated at the beginning of this year to $152.7 billion, a decrease of 35.4%. It is noted that unlike other sectors, seafood simply cannot make up the volume or value in retail because the restaurant industry demands (and pays premium for) the highest value product that retail does not. Also notes the challenge of direct to consumer sales. First, retail is much lower margin than foodservice sales. Marketing is a challenge as most direct to consumer sales takes place online and on social media, a venue the industry is unfamiliar with. Finally there is safety and shipping costs. Amazon has trained consumers to expect the price of shipping to be included in the sale price, and seafood companies have to follow suit. Because shipping is expensive, many of the frozen sellers have minimum order sizes of $99 or $200 to include shipping in the price. This gives frozen sellers an advantage over fresh sellers, who cannot ship higher volumes. It costs just as much to 2-day ship 4 lbs of fresh seafood with FedEx as it does to ship 10 or 15 lbs of frozen seafood. Fresh seafood direct sales are mostly for same day or next day consumption, making it more difficult for them to bear the full shipping cost.” |

|

September 14, 2020 |

A “lull” is established, but many uncertainties face industry including: presidential election, layoffs, virus resurgence (and thus restaurant closures), Wall Street volatility. Notes that foodservice industry will not “snap back” However, three trends will benefit the seafood industry: “ 1) the huge increase in home cooking as fewer people eat in restaurants, 2) the big increase in usage of frozen food, which is especially advantageous for the seafood industry, and 3) continued emphasis on health and diet during the pandemic.” Survey data shows a net 13% increase in retail seafood purchasing. However, clams/oysters showed less than 15% of consumers preparing oysters for home use. |

|

October 22, 2020 |

Surge in demand for home cooked seafood “Last spring consumers learned that they could buy fresh and frozen seafood at retail to replace what they otherwise would have used outside the home and High Liner Foods estimates that approximately 500,000 new customers began buying retail seafood in the US.” This is noted as particularly applied to lobster as “celebratory” seafood. However, “Oysters are another area where production has been low, maintain pricing even in the face of lower sales.” |

|

November 4, 2020 |

Election Impacts: Continued uncertainty due to lack of clear winner, and a continuation of the “COVID Winter”. However, if Biden wins (which he did) less fiscal support for businesses, increasing role of science in fisheries decision making and renewed emphasis on climate change, regulatory decision-making “is likely to become less ideological and more administrative” Remaining danger of economy stalling, however “seafood … representing the most expensive protein, there are a lot of upper income people in the U.S. who are economically secure, and will continue to purchase seafood items. But the loss of foodservice, the hollowing out of the travel industry, the reduction in students living at college, and other negative changes due to the pandemic risk becoming permanent parts of our economic landscape. The lack of a stimulus plan to reverse some of this damage will lead to more difficult business conditions. …The change I was hoping for has not materialized, and if it is to come about, it maybe smaller and more incremental than I expected. But overall, that is not a disaster for the seafood industry, rather it is a continuation of our life in 2020, a difficult, but not impossible, prospect. |

|

December 9, 2020 |

Documentation of decline of restaurant industry, which seafood and oysters are particularly dependent on. “This week, the National Restaurant Association said that 110,000 restaurants, 17% of the total in the U.S., have closed permanently or long term due to the pandemic, something totally outside of their control.” Oyster farming along with salmon called out as especially hard hit by restaurant declining. |

|

December 29, 2020 |

A Summary of developments over the year: 1) Consumers learned to cook seafood at home 2) Foodservice dependent products “like oyster farmers, for example, have simply nowhere to go with their product, and they are suffering huge losses. 3) Access to capital matters. Smaller and weaker producers being bought out. 4) Innovation matters. Rapid move to online ordering and direct-to-consumer selling. |

Methods to IMMERs

Pre-Covid-19

IMMHER Restaurant Inventory Methodology

Based on a sampling strategy introduced in a 2017 working paper released by the National Bureau of Economic Research (Glaeser et al. 2017), we utilized publicly available data about restaurants in the selected cities of Augusta, Macon, Savannah, Atlanta, and Athens, Georgia accessible on the restaurant review website, Yelp.com. Working city by city, the research team searched for all independently operated, high end restaurants in each city demarcated by “$$$” and “$$$$” indicating they were “expensive” ($25-40) or “very expensive” ($50 and higher) per meal/customer (CMS Max 2021). While a sufficient number (220 combined) were identified in Atlanta and Athens, only 33 that met this criteria were identified in Savannah, Macon, and Augusta. Subsequently we broadened the search parameters in those cities to include “$$” or “moderately expensive” restaurants that were independently operated. We revised the list against the following criteria:

- Eliminated restaurants belonging to national chains. Independent restaurants with more than one location were acceptable.

- Restaurants that self-identified as a specific genre that does not typically highlight seafood items on menu were examined closely to determine if seafood was present, and then removed from the sampling frame if it was not (i.e. Mexican, Indian, BBQ)

We then created a restaurant database, compiling restaurant name, address, phone number, active status, and website address. We examined online menus to determine whether oysters were sold at that time. We calculated the average dinner entrée, appetizer price, oyster main course price, and oyster appetizer price. This sampling frame was the foundation for our random sampling. In anticipation of analyzing the data to come from these surveys, we calculated the population and median income of each selected city using United States Census Bureau data for Athens, Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, and Savannah. We planned to compare our final data to determine whether population and income were factors in the number of restaurants and their prices in the selected cities. Tables 3 - 6 of this data are available below (Census.gov).

Table 3. United States Census Bureau Population (city)

|

City |

April 1st, 2010 Census |

July 1st, 2016 Population Estimate |

|

Athens |

115,452 |

123,371 |

|

Atlanta |

420,003 |

472,522 |

|

Augusta |

195,844 |

197,081 |

|

Macon |

91,351 |

152,555 |

|

Savannah |

136,286 |

146,763 |

Table 4. United States Census Bureau Median Income, 2011-2015 (city)

|

City |

Median Income (in dollars) |

|

Athens |

$32,010 |

|

Atlanta |

$47,527 |

|

Augusta |

$37,337 |

|

Macon |

$36,568 |

|

Savannah |

$36, 466 |

Table 5. United States Census Bureau Population (county)

|

County |

April 1st, 2010 Census |

July 1st, 2016 Population Estimate |

|

Clarke (Athens) |

116,714 |

124,707 |

|

Fulton (Atlanta) |

920,581 |

1,023,336 |

|

Richmond (Augusta) |

200,549 |

201,647 |

|

Bibb (Macon) |

155,547 |

152,760 |

|

Chatham (Savannah) |

265,128 |

289,082 |

Table 6. United States Census Bureau Median Income, 2011-2015 (county)

|

County |

Median Income (in dollars) |

|

Clarke (Athens) |

$32,162 |

|

Fulton (Atlanta) |

$57,207 |

|

Richmond (Augusta) |

$37,207 |

|

Bibb (Macon) |

$36,519 |

|

Chatham (Savannah) |

$47,218 |

We subsequently developed survey instruments specifically for the purposes of this project, and applied for IRB approval for this research through both Emory and Georgia Southern Universities. This approval was granted, and data collection began in 2018 and continued through the spring of 2020, when the COVID-19 global pandemic commenced.

Post Covid-19

Qualitative, In-Depth Chef Interviews

COVID-19 decimated our data and research plan for this subject. In order to gather sufficient quantities of currently-accurate data shifted our methodology to semi-structured qualitative interviews with interested professional chefs conducted via phone or video conference. The interviews took between 30 and 90 minutes. In order to identify interview participants, we conducted snowball sampling through existing contacts in the restaurant industries of Savannah, Statesboro, Macon, and Augusta to recruit chefs) to complete qualitative interviews. While they were open-ended in nature, they included key themes such as the following:

- Chef’s primary role in the restaurant? How long have working in the industry?

- Have you personally eaten oysters? Do you enjoy them? What do you like/dislike about them? Do you have any concerns about them?

- Have you ever personally eaten Georgia oysters? What did you like/dislike about them? What are your concerns about them?

- How would you describe your restaurant pre-COVID?

- How important is seafood to your restaurant? Have you ever/do you currently serve oysters in your restaurant? Tell me a little bit about how you serve oysters

- Can you tell me about your customers’ interest in oysters? Do your customers prefer oysters from specific regions?

- As a food buyer, what do you think about when purchasing oysters?

- Have you ever served Georgia oysters in your restaurant? Why/why not? Can you tell me about your experience?

- Would you be interested in serving Georgia oysters in your restaurant? What would be important to you in making that decision? Which would be the best ways for you to communicate about Georgia oysters?

- Where do you currently buy your seafood from?

- Are you willing to receive Georgia oysters directly from the grower via overnight shipping in temperature-controlled packaging? Willing to pay shipping or handling fees? How often would you want to receive a delivery? How many in each delivery?

- How much would you be willing to pay and how would you be willing to pay for them?

- What potential concerns or recommendations do you have about selling Georgia oysters to restaurants like we’ve described?

- How have you and your restaurant been impacted by COVID? How have you changed operation?

- Has the way you buy and serve seafood and shellfish changed since COVID? How has COVID affected your interest in shellfish? Specifically, oysters?

Informed consent documents were emailed to each participant prior to the interview, and verbal confirmation of their informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview, and noted on the interview document. Calls were recorded for later transcription and current and on-going data analysis.

Results on oyster growth and survival

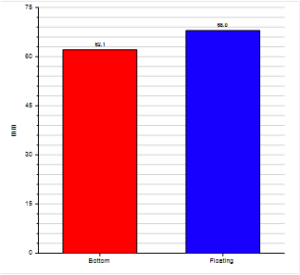

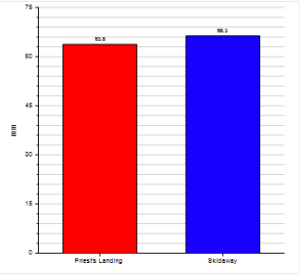

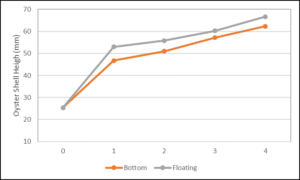

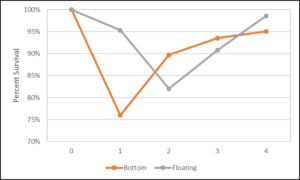

Oysters were set out in March 2020 and grew consistently and by conclusion of the study, February 2021, all oysters had surpassed the minimum harvest size of 50.8mm oyster reached 62.3 mm (+1.03 SE) and 66.9 mm (+1.36 SE) in bottom tubes and floating tubes, respectively (Figure 4). No difference was found between oysters grown at Priest Landing or Skidaway River (p=0.238) (Figure 5), but oysters grown at the surface were significantly larger (p=0.007). Quarterly growth rates were similar between oysters (Figure 6). Cumulative survival was higher in the floating at 70.6% and 64.5% in bottom tubes. Quarterly survival was lowest during the spring for bottom tubes and during the summer months for floating tubes (Figure 7).

Figure 4. Oyster shell height (mm) of oysters harvested from oyster tubes held on bottom and at the surface. Chatham County, GA 2021.

Figure 5. Oyster shell height (mm) of oysters harvested from oyster tubes held at Priest Landing and Skidaway docks. Chatham County, GA 2021.

Figure 6. Quarterly growth of oysters grown in tubes on bottom and at the surface from March 2020-February 2021. Chatham County, GA.

Figure 7. Quarterly survival of oysters grown in tubes on bottom and at the surface from March 2020-February 2021. Chatham County, GA.

Growers wants and needs

Data from the tubes provides additional information to farmers who are interested in growing oysters on their intertidal leases. Growth and survival rates are slightly higher than the 50.4% survival rate observed in bottom cages. The time to handle the tubes took about 45 minutes to pull in and clean a string of 12 cages, a little less than 4 minutes to cage. The biggest benefit of the tubes is that each unit weighs less than 100 pounds when stocked with market size oysters and is therefore easier to handle than bottom cages. With bottom cages, a winch and davit is necessary to pull the cage onto the boat which is cumbersome, and then bags must be removed and cleaned. Or cages must be handled on foot at low tide to remove bags (Figure 8).

With the ongoing development of the Shellfish Mariculture Permit by Georgia Department of Natural Resources, growers will now have the ability to apply to use bottom gear on intertidal leases. The development of water column leases will provide the ability to utilize other gear types, but these leases are limited and requirements to enter the lottery for leases could put them out the reach of some growers. Application for intertidal leases is less stringent and could offer an easier entry for new growers.

Figure 8. Image of bottom cages on intertidal lease. McIntosh County, GA.

Shipping results

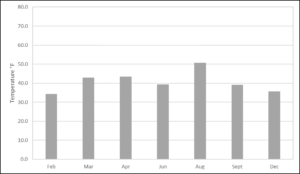

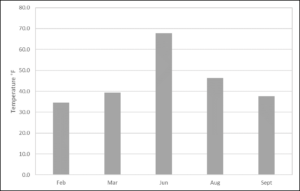

Shipping overnight in Styrofoam coolers had the best success of all methods; 87.5% (7/8) arrived within temperature and only one shipment was out of temperature at 50.6°F, which is over the mandated level of 45°F for molluscan shellfish. All other shipments were at safe temperatures between 35.7-43.5°F (Table 10). Ground shipping in Styrofoam coolers was not consistent; 40% (2/5) of shipments arrived out of temperature, both of which occurred during the summer months of June and August at 46.3°F and 67.3°F, respectively (Figure 11). It is worth noting that the TTIs in the overnight package with the June ground package, that were over temperature, was still green, indicating that oysters had not been out of temperature for long enough time to allow for Vibrio spp. bacteria growth.

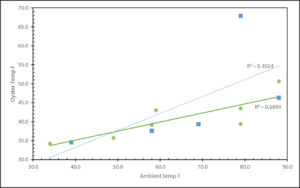

The receiving temperature of oysters within Styrofoam coolers sent overnight were strongly correlated with outside ambient receiving temperature (R2=0.689) (Figure 11). The one package that was out of temperature was when outside temperature was 88°F and occurred in August. Variability in the ground shipments founded a weaker correlation (R2=0.402) (Figure 11).

Recyclable coolers shipped overnight performed poorly with only 25% (1/4) arriving within temperature. Mean delivery temperature was 49.4°F (SE=2.9) and range of (43.3-57.0). Recyclable coolers were sent ground only twice, but were not considered worth carrying forward due to poor receiving temperatures of 55.2°F and 70.5°F. Another problem observed with recyclable coolers was moisture leakage making the exterior cardboard box wet. On one occasion, FedEx refused to ship the package because the cardboard box was wet.

Figure 10. Receiving temperature of oysters shipped in Styrofoam coolers using overnight shipping.

Figure 11. Receiving temperature of oysters shipped in Styrofoam coolers using ground shipping.

Figure 12. Scatter plot indicating receiving temperature of oysters and ambient air temperature when package was received for Styrofoam coolers sent overnight (green) and ground (blue). Regression and R2 is shown for overnight (green line) and ground (blue line).

Time Temperature Indicators (TTIs)

The shellstock TTI (Time Temperature Indicator) by Vitsab® cost $0.59 per tag and are sold in rolls of 500, 1,000, 1,500, or 2,000 and shipping cost is $225. Vitsab TTI’s have a one-year shelf life when kept in the freezer and 4 months when stored in the refrigerator. The TTIs were stored in a freezer and during the first portion of shipping, but we had difficulty with activating the TTI and getting it to adhere to the inside of the cooler. After talking with a Vitstab representative, it was recommended that 24-48 hours prior to shipping, TTIs be removed from the freezer and placed in a refrigerator. Once this change was made, no difficulty in activating or having the TTI adhere to the cooler was experienced. Vitsab Freshtag fact sheet and basic instructions are attached in Appendix V.

Enterprise Budget Results

A market estimate of $0.54 per oyster was used, but the prices of oysters can fetch in the range less than $0.15 to $1.20 (Hudson 2018). Survival estimates observed in the study ranged between 60%-69% and using the lower survival rate of 60%, an estimated density of 250 (based on Ketchum supply) oysters per tube, starting with 200 tubes (50,000 oysters) in year 1, and adding 100 tubes (25,000 oysters) a year in years 2-5 the budget indicates that the business will be out of debt by year 3 and will net $22,935 in year 5.

A similar model was developed for bottom cages and results were similar. The main difference between the two models was due to the $1.00 fee per "cage" that is part of the regulations.

Economic Impact Estimate

The economic impact of the oyster operations in the Georgia economy is presented in Table 1. The direct output impact of $132,500 accounts for an overall impact to the economy of $177,480 once the indirect and induced effects are included. Labor income impacts account for a total of $59,700 per year and involves approximately 2.3 jobs in the economy.

Table 1. Annual Economic Impact Estimates. Source: IMPLAN Group, LLC. IMPLAN [2019 data]. Huntersville, NC. IMPLAN.com. Calculations by UGA Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development.

|

Impact Type |

Jobs |

Labor Income |

Value Added |

Output |

|

Direct Effect |

2.0 |

$45,975 |

$141,431 |

$132,500 |

|

Indirect Effect |

0.0 |

$647 |

$1,153 |

$2,391 |

|

Induced Effect |

0.3 |

$13,079 |

$24,873 |

$42,589 |

|

Total Effect |

2.3 |

$59,701 |

$167,457 |

$177,480 |

IMPLAN Assumptions

IMPLAN is a regional economic analysis software application that is designed to estimate the impact or ripple effect (specifically backward linkages) of a given economic activity within a specific geographic area through the implementation of its Input-Output model. Studies, results, and reports that rely on IMPLAN data or applications are limited by the researcher’s assumptions concerning the subject or event being modeled. Studies such as this one are in no way endorsed or verified by IMPLAN Group, LLC unless otherwise stated by a representative of IMPLAN.

IMPLAN provides the estimated Indirect and Induced Effects of the given economic activity as defined by the user’s inputs. Some Direct Effects may be estimated by IMPLAN when such information is not specified by the user. While IMPLAN is an excellent tool for its designed purposes, it is the responsibility of analysts using IMPLAN to be sure inputs are defined appropriately and to be aware of the following assumptions within any I-O Model:

- Constant returns to scale

- No supply constraints

- Fixed input structure

- Industry technology assumption

- Constant byproducts coefficients

- The model is static

By design, the following key limitations apply to Input-Output Models such as IMPLAN and should be considered by analysts using the tool:

Feasibility: The assumption that there are no supply constraints and there is fixed input structure means that even if input resources required are scarce, IMPLAN will assume it will still only require the same portion of production value to acquire that input, unless otherwise specified by the user. The assumption of no supply constraints also applies to human resources, so there is assumed to be no constraint on the talent pool from which a business or organization can draw. Analysts should evaluate the logistical feasibility of a business outside of IMPLAN. Similarly, IMPLAN cannot determine whether a given business venture being analyzed will be financially successful.

Backward-linked and Static model: I-O models do not account for forward linkages, nor do I-O models account for offsetting effects such as cannibalization of other existing businesses, diverting funds used for the project from other potential or existing projects, etc. It falls upon the analyst to take such possible countervailing or offsetting effects into account or to note the omission of such possible effects from the analysis.

Like the model, prices are also static: Price changes cannot be modeled in IMPLAN directly; instead, the final demand effects of a price change must be estimated by the analyst before modeling them in IMPLAN to estimate the additional economic impacts of such changes.

In-state Market Surveys Results

Interest in Georgia Oysters

Demand for Georgia oysters is far higher than availability. Many chefs we interviewed are aware of Georgia oysters, particularly the E.L McIntosh & Son oyster business, either because they are one of the lucky restaurants able to purchase from the McIntosh family, or because they know the product is excellent and they have made fruitless efforts to source McIntosh’s seafood. The demand for Georgia grown oysters is high, and chefs report this demand would be consistent throughout the year.

Chef and Consumer Education

The desire for chef and consumer education is also strong. Although many of the chefs interviewed were familiar with Georgia oysters, a few had never tasted them, and most expressed interest in increased education for themselves and/or their consumers. Several cited the popular “Oyster South” events in Decatur as excellent examples of successful marketing and education that they suggested be repeated. Some chefs mentioned previous trips to the coast to tour clam farms, and proposed a similar event be held to expose Georgia chefs to Georgia oysters. Other alternative suggestions included a short printed brochure that shared info about the oyster farmers be included in the package, so that chefs can “put it down on my desk and then walk away, put out 100 fires, work dinner service, and then come back and see it and say “oh, I want to look at that, I’m glad I have time now!”

Additionally, a QR code placed on the back of the oyster tag required to be on every bag of oysters would also be a popular method of sharing an easy to access mode of education, as it could link chefs, wait staff, and interested parties to the story of each individual oyster farmer. Instagram was also repeatedly suggested, as many chefs already follow Instagram accounts that belong to their local suppliers. Most interview participants stressed the need to tell the “story” of the seafood and the oyster farmers, in order to pique customer interest and justify a potentially higher price point. As one explained: “whenever there’s a story to tell about a food item, whether it be a heritage breed chicken or an ancient grain that grows at Ansen Mills, or a unique oyster or whatever, I think those kinds of stories resonate with people and you can tell” because it increases sales of the given item.

Direct Marketing and Shipping Methods

Responses to questions about shipping methods were widely diverse. Many of the interview subjects have some experience with receiving seafood sent via UPS or FedEx in styrofoam packages with dry ice. Some participants spoke positively of this experience, explaining that they had never had any problems. Other participants described similar methods, but recounted numerous occasions when these boxes full of highly perishable product arrived days later than expected, containing hundreds of room temperature, rotten, oysters or clams. Temperature gauges in the boxes that record any unsafe temperature levels would ease concerns, as would highly insulated boxes capable of maintaining proper temperatures long beyond the expected shipping period.

Grower interviews

Pre Covid-19

In addition to the scientific assessment of growing success, this project also concentrated on the lived satisfaction with the methods. Before beginning the grow-out methods, CoPI Tookes conducted semi-structured interviews with the clam farmers to identify their reasons for participating in the research, their hopes for the project success, why they feel this is a necessary new strategy to develop, and what concerns they have about the process or product. All reported being cautiously optimistic about the grow-out methods, and confident that a market existed for as much product as they could produce. All three were hesitant about the amount of additional labor that would be required to produce the single oysters, and to also package and ship the live oysters.

Unfortunately, because of long-term logistical restrictions from Georgia DNR on the timing and placement of the new oyster gear from 2018-2019 (which delayed planting), followed by the COVID pandemic, the Co-PIs were not able to access the farmers to conduct any further qualitative interviews about the planting experience or their wants and needs. Casual interviews with the farmers about this process with partnering growers of indicated interest in trying gear on their leases. Growers are also excited that there is now a standard process to request the use of aquaculture gear on intertidal leases and were frustrated at not being able to utilize the gear on their lease during this project, but were grateful to be involved.

Discussion

The growth of oyster aquaculture is poised to increase substantially within the State of Georgia using a combination of methods. As a result of this research in concert with other oyster research, the state has adopted legislation to properly regulate and codify oyster mariculture. The use of bottom gear to grow oysters has a long tradition and although tube cages are used more often to finish off oysters, they do work well to grow oysters to market size from seed. This is extremely important in Georgia since intertidal shellfish leases vary widely in geographical conditions. No two intertidal leases are alike and can be comprised of either large mud flats, tidal rives, small tidal creeks or in combination. Additionally, size is not standard and intertidal leases range from as small as 40 acres to over 4,500 acres. The application of oyster tubes gives information and tools to current and potential intertidal lease holders interested in oyster aquaculture to better utilize their lease. Oyster bottom cages are successful within the right conditions to support the weight of the cage. Oyster growth observed in the tubes in this study, although not ideal, allowed oysters to reach market size within a 15-month time period and with a survival rate of 65% to 70%. This survival rate falls in-between rates observed for from previous studies of diploid oysters grown in floating and bottom cages. Growth rate was also on par with bottom cages, but not as quick as observed with floating cages.

Although intertidal bottom farming is more labor intensive than farming with floating gear, the cost to entry is lower and utilizes established intertidal leases. The oyster crop budget estimates that it is possible to be profitable within a 5-year period. Variables that have not been explored are stocking density and market price of oysters within Georgia. Stocking density plays an important role, and the tubes that we built are slightly shorter and only have a single chamber. Commercially available tubes have an inside divider that could theoretically double the density. A market estimate of $0.54 was used but the prices of oysters can fetch in the range less than $0.15 to $1.20 (Hudson 2018). Survival estimates ranged between 60%-69% and using the lower survival rate, estimated density of 250 (based on Ketchum supply), starting with 200 tubes (50,000 oysters) and adding 100 tubes (25,000 oysters) a year in years 2-5, and an oyster price of $0.54 indicates that the business will be out of debt by year 3 and will net $22,935 in year 5. A slight change in the sales price of oysters can drastically impact profitability. A $0.05 drop reduces profitability to $15,434 in year 5 while a $0.05 increases profitability to $30,435. In addition to farming and determining price per oyster, distribution is key to moving the product to market.

Past research has found that low volumes of oysters is a hurdle to distribution. Shipment of oysters from coastal Georgia is a method that provides an avenue to meet this demand, but business models outside the scope of this project, must be evaluated to determine feasibility since additional infrastructure is required. Surveys indicate that demand for Georgia oysters is high throughout the state, even after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and that Chefs are open to receiving oysters from direct shipment. Our results demonstrate that direct shipment of oysters can be done safely and that the use of TTI’s is viable way to provide food security to the shipment of oysters. Which directly addresses the concern voiced from Chefs about direct shipment. Chef and staff education and training about oysters is also an important component that was identified and there is interest in both passive and active interaction. The lack of education and training has been observed in other states and there is ongoing efforts to address this training through partnership with Oyster South.

Optimism is high with the regulatory changes that provides the ability to conduct oyster aquaculture on intertidal leases. Although we were unable to work directly with growers to evaluate the gear, the results that we did get from research now provides growers with two methods to explore to grow oysters. This in combination with the budget tools, the high demand for oysters, and planned grower training programs indicates that oyster aquaculture is poised to grow in Georgia.

Education

Oyster Grow-out

The plan for educational approach with growers was to provide them the oyster tubes and materials to help with maintenance. Aquaculture extension agent worked with each participating grower and identified a location to set out the gear. If permits had been granted, then aquaculture extension agent would have worked bi-monthly with growers on their lease to get their feedback and assist with tracking oyster growth and survival. This interaction would have provide direct information transfer and would have inferred how to make improvements to the system.

Oyster Shipping

For oyster shipping the aquaculture extension agent worked directly with the three participating growers. Since tubes were not permitted, we utilized oysters from another project for shipment. The agent drove oysters and shipping material to the growers cooler and then worked with them to pack up coolers and illustrated the use of the Vitstab TTI's (time temperature indicator) and the digital thermometer and what temperature information to record. This was direct information transfer to growers.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

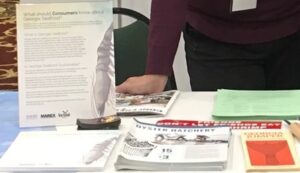

Outreach to restaurants and chefs commenced in February of 2020, with Co-PIs Yandle and Tookes hosting an education table at the widely attended Georgia Organics Annual Conference (Figure 13). Over the course of the two day meeting, we educated numerous chefs, restaurant buyers, and consumers about oyster aquaculture in Georgia. Using oyster shells from the Georgia coast, photos, and videos, we illustrated the proper handling of shellfish as well as the pristine environment in which they are raised. This conference was scheduled to the first event of an “outreach season” as it was to be followed by the Brunswick, GA Blessing of the Fleet in April of 2020, spring/summer meetings of the Georgia Chef’s Collaborative, and concluded with the Savannah Food and Wine Festival in November of 2020. Unfortunately, widespread closures and cancellations meant that none of these events proceeded as scheduled, and efforts and funding were redirected into updated data collection via qualitative interviews.

Figure 13. Tracy Yandle and Jennifer Sweeney Tookes at the Oyster Education Booth at the Georgia Organics Conference in Athens, GA in February of 2020.

Enterprise budget for oyster tubes and bottom cages was created in Microsoft Excel so that it can be easily utilized by growers. This allows for growers to evaluate the two techniques that have been researched in Georgia for use on intertidal bottom leases, both have been attached as excel file. Due to Covid-19 we have been unable to hold a meeting with current lease holders in Georgia to introduce the enterprise budgets and results of the research. Anticipate holding meeting in summer 2021, pending Covid-19 guidence.

Fact sheets on the oyster tubes, shipping, and the enterprise budgets are under development to be released. In addition, all information on the grow-out, shipping, budget, and demand will be incorporated into out Shellfish Aquaculture Training Program for current growers and prospective growers interested in oyster aquaculture. This program was to be started in early 2020, but due to the onset of Covid-19 we were unable to offer. Goal is to reach 20 individuals about shellfish aquaculture.

Learning Outcomes

Project Outcomes

This project in conjunction with research on floating gear for oyster aquaculture provided important information that assisted the state of Georgia in the development of Georgia Code that regulates shellfish. The new code was signed in 2019 and took effect in March 2020 has established a clear path for the regulation and use of gear for shellfish aquaculture. This change in the code, would not have been possible without the data from oyster research on growth and survival. Georgia shellfish leases are still dominated by intertidal-bottom leases and this research demonstrates that using oyster tubes can be successfully employed to grow and harvest oysters. The development of the enterprise budget give current lease holders and potential lease holders a good basis to estimate cost and time to profitability.

Direct shipment of oysters had not been used prior since Georgia harvest was based on bulk wild harvest. With transition to oyster aquaculture one grower Earnest McIntosh, who had permission to use bottom cages for oyster aquaculture on his lease started shipping oysters to restaurants in Atlanta and Athens. This provided an avenue to meet demand without having to deliver in person.

Establishment of oyster farms on leases can provide stability to the oyster industry since they can manage and estimate sales. In addition to farm stability, the environmental benefits of oyster aquaculture are numerous. Oysters help increase water quality, improve adjacent sediments, and gear provides structure that attracts nekton. These impacts have not yet been evaluated in Georgia, but with the development of aquaculture we are working on grants to evaluate the environmental impact that oyster farms have upon the estuaries.