Final report for LS20-340

Project Information

Hedge-pruning of pecan (Carya illinoinensis) trees is a cultural management strategy that has been shown to mitigate effects of tree shading, reduce alternate bearing tendencies, improve tree health and increase orchard profitability. It has been practiced successfully in high-light environments and has become the standard method employed in the arid regions of the southwestern US. Environmental conditions in the southeastern US differ greatly from regions where hedging has been implemented (e.g., in terms of cloud cover and atmospheric water vapor). Thus, it is unclear whether hedge-pruning will be beneficial and sustainable in the Southeast, which is the major pecan-producing region in the US. Research is urgently needed to determine applicability and best management practices for hedge-pruning in the Southeast. Initial studies showed promise for hedge-pruning in the southeastern US. For example, in Georgia, winter hedge-pruned trees had reduced water stress compared to non-hedged trees, and nut weight and percent kernel were increased by hedge-pruning trees in the winter. Hedge-pruned trees also suffered less storm-related injury. Hedge-pruning has a positive impact on the management of scab, the most destructive disease of pecans in the southeastern US. Scab was easier to manage by bringing the nut crop within reach of efficacious spray coverage. Although preliminary studies of arthropod pest populations in hedged-pruned and non-hedged trees showed little difference between treatments implying that hedge-pruning does not increase pest pressure, there were indications that hedge-pruned trees had reduced injury from black pecan aphids, Melanocallis caryaefoliae, a major insect pest in pecans, and had increased aphid parasitism early in the season.

In recent years in the Southeast, hedge-pruning pecan has gained popularity among growers. Therefore, research is warranted to determine the ecological and economic sustainability of hedge-pruning in the southeastern region. In fact, pecan hedge-pruning is listed as a major research priority identified by the Georgia Pecan Growers Association. There are unknown ramifications of hedge-pruning that must be addressed. Specifically, the impact of hedge-pruning younger trees versus older trees is unknown, and the effect of timing of hedge-pruning (summer versus winter) on the tree, and impact on critical pests and diseases is preliminary. In relation to these aspects, we propose assessing critical horticultural parameters (nut yield, quality, water-use efficiency, and nutrition), disease (incidence and severity of scab, colonization of branches by wood rot fungi), insect pest and natural enemy populations and pest-related injuries. Moreover, hedge-pruning trees may result in changes in the quantity of radiant penetration to the understory, impact soil moisture and affect the biotic community. Thus, we will evaluate impacts of hedge-pruning on soil-borne entomopathogens that provide biocontrol services against soil inhabiting pecan pests including pecan weevil, Curculio caryae. There will be a comprehensive economic analysis and implementation of Extension and Outreach programs based on the research results. Findings from these studies will be beneficial to other orchard and tree nut production systems where hedged-pruning is practiced.

Our main goal is to evaluate the sustainability of hedge-pruning pecan trees in the southeastern US. Prior research demonstrated that hedge-pruning can have positive impacts on some horticultural parameters, and can improve disease and insect management. However, the relative benefits of hedge-pruning trees of different ages, or hedge-pruning trees at certain times of the year is not known. We propose the following objectives:

1) Determine relative impacts of hedge-pruning young and older trees by comparing horticultural and production variables, disease and insect pest prevalence, and natural enemy populations in hedged-pruned and nonhedged young and older pecan trees.

2) Define the effects of timing (summer versus winter) of hedge-pruning of pecans on the variables listed in objective 1.

3) Perform an economic feasibility assessment of hedge-pruning pecan based on the results obtained from objectives 1 and 2.

4) Share the results with growers and other stakeholders via diverse Extension and outreach programs.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor (Educator)

- (Educator)

- - Producer (Researcher)

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Multi-disciplinary team

- Plant Pathology (Clive Bock, USDA)

Determine relative impacts of hedge-pruning young and older trees by comparing disease in hedged-pruned and non-pruned young and older pecan trees. Define the effects of timing (summer versus winter) on hedge-pruning of pecans.

At all locations, scab assessments were made on leaves and fruit at two points during the season - the first sample was taken when fruit were immature (late June/early July), and the second sample when fruit were mature from mid-August to mid-September 2020-2022. Scab assessments were also taken on the shoots in January of 2021 and 2022. Depending on the experiment, samples were collected at up to 4 heights. Ten compound leaves and ten fruit were collected at each height on both row-sides of each sample tree. Samples were collected using a hydraulic with sample heights measured using an Opti-Logic Laser Rangefinder (Opti-Logic, Tullahoma, TN). Leaf samples were assessed for severity of pecan scab based on the percent area diseased was visually estimated on each leaflet of each compound leaf. Scab on fruit was assessed similarly - pecan fruit are comprised of four valves joined along their edges by a suture, and each of the four valve faces was assessed individually for severity of pecan scab based on the percent area diseased. Assessments were aided by validated standard area diagrams for scab severity on both leaves and for fruit. Fruit fresh weight was determined individually at the time. Shoots were measured and the number of scab lesions counted for each shoot. Data were analyzed in 2021-2023 using a generalized linear mixed model with fixed effects of treatment, tree height and tree side, and random effects of replicate.

- Entomology (Angel Acebes-Doria and Jason Schmidt, UGA)

Determine relative impacts of hedge-pruning young and older trees by comparing horticultural and production variables, disease and insect pest prevalence, and natural enemy populations in hedged-pruned and non-pruned young and older pecan trees. In the second year of the project we collected pest, natural enemy, and leaf samples from trees under the different management strategies. Currently we are working through the samples. We brought on a PhD student in early 2021, and he began processing the samples from the 2020 season, and then with our total team mobilized for collecting, the MS student (Kate Phillips) and PhD student (Pedro Toledo), along with undergraduate research assistants, collected the data. We have currently finished counting insects from sticky cards, and leaf samples, and have presented the work. In addition, our team is working on a manuscript. During sampling, we also took suction samples of the pecan canopy to better characterize less mobile predators in the canopy, and to assess parasitism rates on aphids (i.e. ratio of aphid mummies/aphids). Our sorting of samples so far has provided over 2000 individuals, and we are still working through the samples. Collection of insects from all participating growers continued through 2021, and in 2021, we added an additional controlled site at the Byron, USDA station. We were worried about controlling some of the management practices and also having the change in hedging where the grower at one site removed entire rows of trees. At the Byron site we collected arthropod samples similar to other sites but had control over insecticide and fungicide use combined with hedging treatments.

- Entomopathogen (David Shapiro-Ilan, USDA)

During the second year of the project, we again collected soil samples in hedged vs. non-hedged trees to assess impact on entomopathogen. This was conducted at the Byron location. As in previous years, primarily entomopathogenic fungi were observed but also some entomopathogenic nematodes. The overall effect showed significantly higher entomopathogen populations (based on insect baiting) in the hedged treatments relative to non-hedged. These data are currently being analyzed and prepared for publication.

- Horticulture Specialist (Lenny Wells, UGA)

The Extension Horticulture Specialist for pecans at the University of Georgia took the lead on presenting work from the project directly to growers and publishing on economic and environmental sustainability of hedging in pecan production in Georgia.

- Economic Specialist (Greg Colson, UGA)

In charge of survey of growers and research on economic viability of hedging for pecan production.

The studies proposed here will be conducted at the following locations:

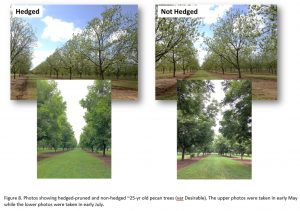

Experiment Site 1: Marshallville, GA where ~25-yr old hedge-pruned trees will be compared with non-hedged trees. Please refer to Fig. 7 for more details on the site and hedge-pruning program. The trees were hedge-pruned on alternate sides since 2013, and due to the relatively young age the tree height is still comparable between hedge-pruned and nonhedged trees (~35 ft); but overall tree canopy volume and row interference is contrasts (Fig 8).

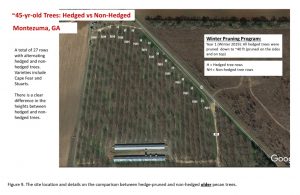

Experiment Site 2: Montezuma, GA where ~40-yr old hedged-pruned will be compared with non-hedged trees. Please refer to Fig. 9 for more details on the site and hedge-pruning program. Older trees were hedge-pruned on the sides and top, thus hedge-pruned trees are considerably shorter (~40ft) when compared to the nonhedged trees (~60ft).

Experimental Site 3: Ray City, GA where ~30-yr old summer hedge-pruned trees will be compared with winter hedge-pruned trees. Please see Fig. 10 for more details on the site and the hedge-pruning program.

All trees in the experiments (hedged and non-hedged) will be receiving the standard grower management including irrigation, spray inputs, fertilizer, etc.

Across all comparisons, treatment blocks are replicated accordingly at each site. Data will be analyzed using standard statistical methods including, but not limited to analysis of variance and regression analysis (Steel and Torrie 1980, Cochran and Cox 1957).

The following are the variables that will be collected, obtained and analyzed from the trees in orchards comparing the different hedge-pruning treatments as described above.

- Assessment of production (nut quality and size), water and nutritional status. Methods to be followed will be based on that of Wells (2018). Midday stem water potential will be determined using a pump-up pressure chamber (PMS Instruments, Albany, OR) by measuring the water potential of leaflets located near the trunk or a main scaffold branch at mid-day. Soil moisture will be measured with a Field Scout TDR 300 Soil Moisture Meter (Spectrum Technologies, Aurora, IL) at 20 cm depth within the wetted zone of irrigation on each sampling date at the same time that stem water potential is measured for each tree. All plots will be mechanically harvested separately. In-shell nuts will be dried to 4.5% moisture with a commercial drier and processed in a commercial cleaning plant to remove all sticks, leaves, and debris. All cleaned nuts will be weighed by plot to obtain in-shell nut yield for each plot. A 50-nut sample will be obtained from each plot at harvest to determine nut size and quality (percent kernel). The effects of hedge-pruning on nutritional status of dormant and summer hedge pruned trees will be assessed through leaf and soil sampling of each plot. Samples of 50 pairs of leaflets will be collected randomly throughout each plot and analyzed for all macro and micro-nutrients. Temperature, light intensity and relative humidity in tree canopy will also be recorded. Cooperators: Wells, Jaros, Levi, Paulk

- Assessment of incidence and severity of disease.

2a. Assessing scab in trees. Methodologies will be the same in all experiments. Samples will be collected at up to four heights (in hedge-pruned trees only 3 heights). Ten compound leaves, fruit (mid and late season samples) and shoots (only late season) will be collected at each height on both row-sides of each sample tree using a hydraulic lift at approximately 5, 8, and 11 and 14+ m. Heights above ground will be measured using a laser rangefinder at the time of sample collection. Leaf and fruit samples will be assessed for severity of scab based on the percent area diseased by visual estimation on each leaflet and on each of the four valve faces. Assessments will be aided by previously developed standard area diagrams for leaflets and fruit. At the end of the season, the length of a sample of 10 shoots from each height in each tree will be measured and the number of scab lesions counted (scab lesions on shoots are considered a potential important source of inoculum for the following season’s epidemic). Methodology will be based on Bock et al 2017.

2b. Assessing tree limb colonization by wood rot fungi. Trees in orchards at the Marshallville site which has been hedge-pruned since 2013 will be monitored for wood rot fungi. A total of 100 trees (50 hedge-pruned and 50 non-pruned) will be surveyed annually to determine incidence of wood rot colonization by visually assessing all limbs in the trees for evidence of fruiting bodies of common fungi (including but not limited to Trametes versicolor and Schizophyllum commune). Species identification will be based on morphology and, if available for the fungus, PCR diagnosis (Chen et al., 2015).

Cooperators: Bock, Jaros, Levi, Paulk

- Assessment of insect pest populations, insect-related injury and beneficial insect populations.

3a. Monitoring of insect pest populations and insect-related nut injuries. Across all studies, standard monitoring approaches for scouting pecan insect pests will be followed (Grantham et al 2002, Reid 2002). We will sample leaves for live aphids, parasitized aphids and mites at three distinct periods in the crop phenology coinciding with the grower management programs for these pests: post-pollination (mid-May), rapid nut sizing stage (July) and kernel filling stage (late August). A minimum of 100 leaf samples will be taken from the lower and upper canopies of trees for each treatment in each experiment at each sampling date. Leaf samples will be placed in Ziploc bags upon collection, and placed in coolers during transport to the lab where they will be examined for the target pests under the microscope.

Periodic collection of nut samples to assess for insect-related injury will be conducted in late May for pecan nut casebearer injury, in late June for shuckworm and nut curculio infestation, and at harvest for pecan weevil, shuckworm and stinkbug attacks. Samples will be taken from the lower and upper sections of the trees, placed in Ziploc bags and will be taken to the lab for examination. A minimum of 100 nut samples will be collected from each treatment in each experimental site per sampling date.

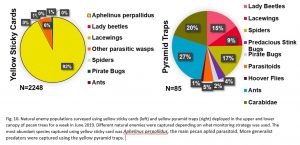

3b. Investigation of the natural enemy populations. We will be deploying yellow sticky cards in the lower and upper canopy of trees for one week during distinct periods in the season: post-pollination, rapid nut sizing and kernel filling stages. A minimum of 10 yellow sticky cards will be deployed per treatment at each experimental site per trapping period. We decided to use yellow sticky cards as these were proven to be effective in monitoring for pecan aphid parasitoid, Aphelinus perpallidus (Fig. 10). The parasitized aphids collected during the leaf sampling, as described above, will be separated and reared until parasitoid emergence for assessment of parasitism rates. Another sampling methodology (e.g., using small pyramid traps deployed in the lower and upper canopy of trees for a week) may be explored to survey other generalist predators such as coccinellids and spiders (Paulsen et al 2011, Fig. 10).

Cooperators: Acebes, Schmidt, Jaros, Levi, Paulk

- Assessment of belowground entomopathogens. Methods to determine persistence of entomopathogens will be based on those described by Shapiro-Ilan et al. (2003, 2017b). Six soil cores will be taken 1 meter from the trunk and another six cores will be taken from the 1 m distance from the trunk to just inside the dripline (approximately 3 meters) of a hedge-pruned and nonhedged pecan tree. It is important that the longer distance remain inside the herbicide strip (not into the grass beyond the strip). Samples will be pooled from within each distance (so each tree has three pooled samples, one from each distance). Soil will be brought back to the lab (in a cooler) and will be exposed to bait insects (greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella). Koch’s postulates will be conducted to verify the presence of entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi. Identification of entomopathogens will be conducted by Shapiro-Ilan and if additional verification is needed by the USDA-ARS collection curators (Shapiro-Ilan holds an International Collection of entomopathogenic nematodes and is versed in identification of entomopathogenic fungi as well). Mortality in bait insects due to entomopathogenic fungi nematodes and overall mortality will be compared among treatments using standard statistical approaches (Steel and Torrie 1980). Samples will be taken bi-weekly during April to October. Cooperators: Shapiro-Ilan, Jaros, Levi, Paulk

- Economic analysis, Extension and Outreach.

5a. Economic analysis. In conjunction with the various field trials, an economic analysis will be conducted to assess the economic costs and benefits of pecan hedge-pruning strategies relative to non-hedged orchards and the timing of when hedge-pruning is conducted. This is a critical component not only to evaluate the efficacy of pecan hedge-pruning, but to also deliver clear recommendations to growers as part of the larger extension and outreach program, and help guide future orchard-level research on pecan hedge-pruning. The economic analysis will synthesize the findings of the various orchard trials with input and output price data. Using standard statistical and extension budging methods, estimates of the relative profitability of hedge-pruning vs. nonhedging and summer vs. dormant hedge-pruning will be evaluated by incorporating the orchard trial results on tree health (e.g. disease and pest rates), production measures (e.g., nut size, yield, and quality), input costs (e.g., labor rates, equipment, water usage), and market price data into a grower-level economic analysis and enterprise budget. Further, sensitivity analysis including multivariate econometric modeling, inclusion of temporal considerations, and production practice transition costs (Lima et al., 2013) will be conducted.

Overall, the economic feasibility assessment and sensitivity analysis will yield estimates (with confidence intervals) of the expected costs and benefits of pecan hedge-pruning relative to not hedging. However, as revealed in previous research, non-monetary considerations such as grower risk perceptions, subjective beliefs of new production practices, and information and experience have been found to influence risk management and technology adoption decisions (Menapace, Colson, and Raffaelli, 2013; 2015). Hence, to complement the economic analysis and aid in the development and refinement of the extension and outreach materials and programs, grower surveys will be administered to assess grower perceptions and knowledge of hedging strategies for pecans. The surveys will be administered in conjunction with the planned extension and outreach grower meetings and field days.

5b. Extension and Outreach Programs. Extension and Outreach programs will be conducted including demonstration trials, grower, industry and scientific meetings. Results will be published via print (magazines, spray guides, fact sheets) and online resources (blogs, apps, websites). Please see the detailed description of our Extension and Outreach programs in the “Information Dissemination and Outreach Plan” section. Drs. Acebes, Schmidt, Hudson and Wells have Extension responsibilities in the southeastern US.

Cooperators: Colson, Acebes, Schmidt, Hudson, Shapiro-Ilan, Bock and Wells

Research and extension result summary

- There were no profound effects of hedging on scab severity, and there was no difference in scab severity on trees hedged in the winter or summer. In more mature pecan orchards with tall trees (>15 m), there were some differences – hedged trees had significantly or numerically less severe scab. Height appears to be important for predicting scab severity. This is likely due to the fact that spray coverage is limited at heights >15 m, precluding efficacious scab control. In these trees scab is more severe in the upper canopy as compared to the lower canopy. Therefore, hedge-pruning likely benefits overall scab severity in taller pecan trees in mature orchards, and also those more scab-susceptible cultivars where better coverage of fungicides with air-blast sprayers is required to control the disease.

- We discovered a diversity of hyperparasitoids parasitizing the primary parasitoid of aphids, which opens a new area of study for understanding natural enemy interactions and food webs within pecan systems.

- Insect responses to hedging were varied, and some pests benefited while others were reduced. Therefore, the effects of hedge pruning pecan canopies were species specific, and not generalizable for all pests or natural enemy groups.

- No clear pattern of hedging on entomopathogens was revealed, as higher activity of entomopathogens was observed in the first year but lower in the second.

- Many growers were reached through workshops and extension activities, and many papers were submitted, published or in review currently.

Economic analysis summary of hedging effects

Analysis of the economic barriers and drivers of adoption of hedge-pruning as a management practice by pecan growers in Georgia revealed that (a) there is only a small to moderate knowledge gap regarding hedge-pruning as a method to manage the size of mature pecan trees, (b) there is only a small perception gap regarding the benefits of hedge-pruning, with the majority of growers already perceiving there are positive benefits in terms of nut quality, nut yield, and pest pressures, and (c) there is a significant action gap due to the cost of hedge-pruning. The economic analysis found some support for the action gap, particularly for small- and medium-sized pecan growers. Combining evidence from a survey of pecan growers in Georgia with market data, UGA Extension publications, and UGA Extension pecan enterprise budgets, the economic viability of small and medium-sized pecan growers purchasing hedge pruning equipment that approximately costs $300,000 in addition to operational costs, maintenance and repairs, and labor expenses, is prohibitive. For a purchase to be economically viable, an alternative strategy, such as a machinery-sharing agreement among multiple smaller-acreage pecan growers would be required. For larger growers who can spread the fixed cost of the initial outlay or financed expense for hedge-pruning equipment over sufficient acreage, the potential return from equipment purchase and hedge-pruning adoption has the potential to be positive due to the benefits to nut production and reduced risk to susceptibility. As an alternative to equipment purchase, custom hedge-pruning presents a potential alternative option for pecan growers, particularly small- and medium-sized producers. Custom hedge-pruning rates of $250 per acre, conducted on a 3- or 4-year cycle, represent, on average, an increased per-acre cost of 3-4% per year for an established orchard, requiring an approximate 3% increased yield-quality return for payback. For a grower assessing the cost-benefit of adopting hedge-pruning, the availability of custom operators in Georgia to maintain the pruning cycle is a limitation. Overall, evidence from the analysis of the economic barriers and drivers of adoption indicates there is interest by growers and perceptions of benefits, that could be further reinforced with further research and longitudinal studies, but the cost dimension and opportunities to reduce this barrier are critical for overcoming the action gap and achieve wider adoption of hedge-pruning of pecan trees by growers in Georgia.

Education

During the course of the project, numerous extension talks were provided and visits to farms. The three participating farms worked closely with the team on all aspects of the project over the project period. At extension events and workshops we successfully reached industry, growers and other researchers. Work is published, in review or in preparation for publishing, and there are still data that will be worked on for future publication on insects. The insect community data was overly ambitious in our sampling, and so we will continue to work on this while we begin other projects, and continue to publish results on insect communities and biological control in the system.

Economics brief summary

- A significant majority of pecan growers perceive positive impacts of hedge-pruning resulting in improved revenues for their operation including:

- Improved nut quality (93% of growers agree) and nut yield (69% growers agree).

- Reduced pest pressures and improve spray coverage.

- Lower risk of wind damage.

- Cost and insufficient evidence of effectiveness and profitability are the most significant barriers to adoption of hedge-pruning by growers.

- 72% of growers perceive the cost of hedge-pruning to be expensive.

- Slightly less than half of growers thought the improvement in revenue would outweigh the cost, with 12% of growers stating that hedge-pruning would reduce farm profits.

- Many growers stated that to evaluate whether to adopt, they need more evidence on (i) the effectiveness of hedge-pruning on operations similar to their own and (ii) the economic returns from the practice.

- The average pecan grower can be characterized as:

- Interested in potentially adopting hedge-pruning for their operation.

- Perceiving positive financial revenue impacts from hedge-pruning.

- Significantly concerned about the cost (equipment and labor) of hedge-pruning.

- Requiring more information and evidence before adoption.

Graduate student training:

Kate Phillips (MS Student)– Finished M.S. degree and defended May 2022.

Pedro Toledo (PhD Student) – 2.5 years into his program. Has collected data from all sites, and is currently processing. He’s now trained on many aspects of working in pecan systems. He also successfully applied for a SSARE student grant to enhance work in pecan systems and predator-prey interactions. Project allowed him to learn a lot more about the communities of natural enemies and interactions with pests in this system. He will contribute 2-3 scientific publications from this work and also a natural enemy informational product.

During the project, four Masters of Agribusiness students were introduced to the unique challenges of budgeting and economic analysis for pecans and other tree crops compared to annually planted row crops in Georgia. Students learned how to incorporate market discount rates into the budgeting process and the importance of sensitivity analysis when considering crops with high upfront costs and long durations of economic returns. As well, using pecans as a motivating case study, approximately 15 students per year were introduced to the concepts of net present value, break-even analysis, and real options analysis as economic tools that can be used to look at financial streams of inflows and outflows for business operation.

Undergraduate student training:

During years of the project, seven undergraduates were trained on multiple aspects of conducting field research in pecan systems. All students learned how to drive the lifts, collect each type of sample, sort collected samples, and for insects, identify basic groups of insect taxa. Others learned basic molecular processing, and data management. We have one student that received a supplementary grant from UGA to pursue independent work, and we anticipate one publication from this work next year.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Below are list of presentations related to this project:

Extension educational presentations to growers, industry, and agents:

Pedro Toledo. 2023. Hedging pruning pecans: Potential implications of hedge pruning for pest management.Southeastern Pecan Grower Association (SEPGA) Annual Conference. 115th Annual Convention & Trade Show – Gulf Shores, AL

Pedro Toledo. 2023. Hedging pruning pecans: Potential implications of hedge pruning for pest management. Georgia Pecan Grower Association (GPGA) Annual Conference 58th Annual Educational Conference and Trade Show – Perry, GA

Wells, L. 2023. Hedge Pruning of Pecan. Georgia Pecan Growers Association Beginners Pecan Course. Perry, Georgia. March, 2023 (Oral Presentation)

Wells, L. 2022. Hedge Pruning Strategies for Pecan. Georgia Pecan Growers Association Fall Field Day. Tifton, GA. September, 2022. (Oral Presentation)

Acebes-Doria, A.L. 2021. Updates on UGA Entomology Pecan Research: Ambrosia Beetles, Pecan Aphids and Pecan Hedge-pruning. Georgia Pecan Grower Conference. Perry, GA, June 3

Workshops:

2021 Virtual Orchard Tour at the Georgia Pecan Growers Association's Annual Conference

2021 Pecan Grower Meeting – the hedging block project in Marshallvile was shown and discussed with the growers.

Scientific Presentations:

Toledo, P., Acebes, A., & Schmidt, J.M. 2023. Pest and beneficial arthropod responses to hedging in southeast USA pecan systems. Invited symposium: Biological Control and Biopesticides, XII European Congress of Entomology, Crete, Greece 16-20 October.

Wells, L. 2023. Use of Mechanical Hedge Pruning to Transition Southeastern U.S. Pecan Production to a More Profitable and Sustainable System. IX International Symposium on Walnut & Pecan. Grenoble, France. (Oral Presentation). June 14, 2023

Pedro Toledo. 2023 .Georgia Entomological Society Annual Meeting 2023 – Helen, GA

Pedro Toledo. 2022. ESA, ESC, and ESBC Joint Annual Meeting 2022 – Vancouver, Canada

Toledo, P.F.S.; Schmidt, JM.; Acebes-Doria AL. 2021. Do mechanical hedge-pruning strategies influence the activity of parasitoid wasps in pecan orchards? Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America. November 1. Denver, CO. Oral presentation.

Toledo, P.F.S.; Phillips, K.; Schmidt, JM.; Acebes-Doria AL. 2021. Effects of mechanical hedge-pruning on aphid-parasitoid interactions in southeastern US pecan orchards. Southeastern Branch Meeting of the Entomological Society of America.

Phillips, K., Acebes-Doria, A., Schmidt, J., Hudson, W. 2021. Impacts of hedging versus thinning on arthropod pest populations in pecan. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America. November 1. Denver, CO. Oral presentation.

Learning Outcomes

More work is needed on the combined effects and costs of doing hedging. With the many effects on insects, this area needs further work.

Project Outcomes

During the course of the project, numerous extension talks were provided and visits to farms. The three participating farms worked closely with the team on all aspects of the project over the project period. At extension events and workshops we successfully reached industry, growers and other researchers. Work is published, in review or in preparation for publishing, and there are still data that will be worked on for future publication on insects. The insect community data was overly ambitious in our sampling, and so we will continue to work on this while we begin other projects, and continue to publish results on insect communities and biological control in the system.

Multiple students were trained and have either secured new positions or are finishing work started under this project.

Combined analysis of communities of arthropods and economics of doing hedging point to new questions we will be working on as we complete the publications from data collected during this project.