Final report for LS21-354

Project Information

Biofertilizers are defined as organic substances containing various microorganisms that improve soil and crop productivity. Cyanobacteria have become an important addition to biofertilizers due to their enhancement of crop production and soil health. However, abundance of cyanobacteria in water can develop hypoxic conditions and cause harmful effects to aquatic organisms. Lake Okeechobee and St. Lucie River of Florida are frequently subjected to cyanobacterial ‘blooms’ that degrade water quality and incur significant environmental, ecological, economic, and societal impacts. Cyanobacterial blooms covered 60% (894 km2) of Lake Okeechobee during June-October 2018. Chemical treatments attempted to manage cyanobacteria population of the Lake have not been successful and created unintended water quality issues. Therefore, we propose to physically remove cyanobacteria from the Lake and utilize the resultant materials as biofertilizer for sustainable tomato and okra production.

Cyanobacteria biofertilizer provide macro and micro-nutrients in the soil and improve nutritional properties (antioxidant, anthocyanin, carotenoids, and chlorophyll contents) of vegetables. Cyanobacteria also increase soil organic carbon (SOC) accumulation, improve soil structure and biodiversity, enhance soil enzymatic activities, and protect plants from pathogens. We estimated that cyanobacteria biofertilizer would reduce 40% fertilizer cost than synthetic fertilizers for vegetable productions. Nutrients in cyanobacteria biofertilizer are in organic form and will be released slowly as the materials decompose. This process is similar to commercially available slow-release fertilizers, that have become standard practice in reducing nutrient leaching and water quality protection. Therefore, this approach is expected to increase return on investment (ROI) of agricultural growers while preserving ecosystem quality. To our knowledge, no field-based experiment in the US have evaluated the effects of cyanobacteria biofertilizer on crop productions and soil health.

This three-year study will evaluate (1) the efficacy of cyanobacteria biofertilizer in improving crop productivity and soil health, (2) the soil and water quality parameters from agricultural fields treated with cyanobacteria, and (3) the economic efficiency of replacing synthetic fertilizer with cyanobacteria biofertilizer.

We are collaborating with the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and AECOM company to collect cyanobacteria from Lake Okeechobee using micro-flotation techniques. Collected cyanobacterial mats will be processed and packed as biofertilizer at Florida International University. We will test the efficacy of cyanobacteria biofertilizer for vegetable production both at FIU greenhouse and cooperative farmer's field. Yield parameters and compositional analyses of tomato and okra will be determined. Physicochemical and microbiological parameters of soils will be measured to evaluate the effect of biofertilizer in agricultural fields.

Cyanobacteria samples (n = 8) collected from Lake Okeechobee showed 1.79% N (similar to other organic fertilizers), 19.6% total C, high Fe (2005 ppm), other micro-nutrient contents, and lower C:N ratios. A preliminary pot experiment growing okra using cyanobacteria biofertilizer showed (at 7-weeks) similar plant height (69 cm), stem diameter (11.2 mm), and leaf chlorophyll content (51) compared to synthetic fertilizer and higher values than unfertilized control pots.

We expect major outcomes of this project will be restoration of Lake Okeechobee ecosystem, higher crop production and revenue generation, soil health improvement, and educational benefits to growers and students on organic agriculture.

Project report summary - Annual report (04/01/2022)

This year (2021 to 2022) annual report includes:

- Updated project objectives and specific goals

- A detail description of how cyanobacteria materials were collected from lake Jesup, Central Florida with the help of algae harvester made by AMECOM company

- Processing of the materials at Florida International University (FIU) for biofertilizer preparation,

- Set up research experiments at FIU greenhouse,

- Results - some data collected as crops are still growing,

- Issues during crop production, and

- Brief extension activities.

Project report summary - Final report (11/14/2024)

This final report is prepared by Dr. Jazmin Locke-Rodriguez, who was brought on as a Post-Doctoral researcher for this project in April 2024 to execute final field trials and conclude outreach activities on behalf of this award under the supervision of Dr. Krish Jayachandran. Below is a list of final updates provided and their location in this report.

- Field trial objectives

- Approach details on large scale biofertilizer processing

- Experimental Design and methods of field trials

- Preliminary Results from field trials

- Outreach activity updates

- Project Outcomes updates

Overall, this project will follow a system-based research approach where optimum crop yield can be obtained without disrupting the harmony of multiple sustainability components (environmental, ecological, economic, and social). This project will address the key question: “Can we increase overall agricultural sustainability by using the waste product of one system as a viable resource for another?” Specific objectives of this project are:

1) To evaluate the chemical and nutritional properties of cyanobacteria collected from Lake Okeechobee and the St. Lucie River ecological areas of Florida

We propose to quantify pH, organic matter content, essential macro (N, P, and K), secondary nutrient (Ca, Mg, and S), and micro (Fe, Zn, Mn, B, Cu, Mo, Cl, and Ni) plant nutrients available in cyanobacteria samples. Cyanobacterial mats will be collected from various locations of the Lake and surrounding area for chemical analyses. We hypothesize that analyses of nutritional and physicochemical properties of cyanobacteria will assist in developing efficient fertilizer application planning in the greenhouse and field trials.

To ensure the safe use of cyanobacteria biofertilizer in the field, microcystin (a common cyanotoxin) concentrations of collected cyanobacterial mats will be analyzed in the laboratory at different stages of biofertilizer development. This experiment will be based on previous study conducted by Co-PI, Dr. Jayachandran and colleagues (Ramani et al., 2012) who found that more than 75% of the cyanotoxins were degraded within 3-weeks after cyanobacteria harvesting from Lake Okeechobee. Our team estimated that it will take about 45 to 50 days to process the fresh cyanobacteria mats into a dried biofertilizer powder (collection, transportation, drying, grounding, and packing). Therefore, the rate of cyanotoxin degradation over time will be calculated from day of collection (time zero; T0) to 50 days after collection (prior to crop application; T50). We will measure the cyanotoxins in cyanobacteria samples every 10 days to develop the ‘decay rate curve’ of the toxin in biofertilizer. We hypothesize that microcystin concentrations in the cyanobacteria biofertilizer will be degraded to less than 1 ppb (WHO standard guideline) and safe for field application.

Additionally, we will test the shelf-life of the cyanobacteria biofertilizer. Some cyanobacteria biofertilizer samples produced in first year (2021-2022) will be kept in a cool, dry place and the nutritional properties of those samples will be analyzed in project years 2 and 3 to determine the shelf-life of the fertilizer.

2) To assess the efficacy of biofertilizer application for crop production and improving soil health

In first section of this objective, we will quantify yield and physiological parameters of tomato and okra at different plant growth stages both in a controlled environment (FIU greenhouse) and in field trials (collaborative farmer’s field). We hypothesize that the application of cyanobacteria biofertilizer will improve soil fertility and increase crop production. The second section of this objective will test the effect of cyanobacteria biofertilizer in improving soil health which is specifically important in South Florida where organic matter content is less than 1%. We hypothesize that extracellular polysaccharides released by cyanobacteria in the soil will improve overall soil health components (soil aggregate stability, soil bulk density, and water holding capacity). Measuring different fractions of soil carbon (total C, organic C, particulate C) will provide us the idea of different ecosystem services cyanobacteria biofertilizer can offer.

4) To assess the economic benefits of biofertilizer application for vegetable productions in Florida

We will run stochastic economic models to integrate inputs (seeds, fertilizer, labor etc.) and outputs (crop yield, price, market demand etc.) for assessing the economic benefits of cyanobacteria biofertilizer in tomato and okra productions. We realize that there are uncertainties with crop yields, costs, and market prices under both conventional and proposed organic farming approaches. The stochastic economic model will utilize a Monte Carlo approach to account for the above uncertainties and help assess incremental (additional) net profits and variability in returns. We hypothesize that organic farming will generate higher profits as well as lower economic variability (risks) for growers than conventional farming practices.

Update - Project Objectives for year 2022 (greenhouse experiment)

1) To evaluate the chemical and nutritional properties of cyanobacteria collected from lake Jesup

- Macro and micronutrient contents of dried and ground cyanobacteria biofertilizer

- Other chemical properties such as pH, OM content of the biofertilizer

2) To assess the efficacy of biofertilizer application for crop production in the greenhouse setting

- Evaluate the beneficial effects of cyanobacteria biofertilizer on different plants

parameters (plant height, stem diameter, leaf chlorophyll contents, and crop biomass at

harvesting) for both okra and tomato.

- Nutritional properties of leaf samples of okra and tomato at different plant growth

stages

3) To evaluate the microcystin contents in cyanobacteria materials

- Microcystin concentration of cyanobacteria samples immediately after collection and at

every 12 days interval till 60 days after collection

Update - Project Objectives for year 2024 (Field experiments)

- To assess large scale biofertilizer drying and processing techniques

- To confirm consistency of chemical properties of stored biofertilizer

- To compare efficacy of biofertilizer applications on okra production with alternative organic fertilizers including vermicompost and traditional hot compost. Trial replications were conducted across three different South Florida Farms.

- To engage farmers, undergraduate students and highschool students in sustainable agriculture research approaches and techniques.

Research

Approaches and Methods:

The USACE has an ongoing project (Harmful Algal Bloom Interception, Treatment, and Transformation Systems; HABITATS) in collaboration with AECOM (an International company; website: https://aecom.com/) to remove cyanobacterial blooms from Lake Okeechobee and adjacent canals. The USACE and AECOM agreed to assist in collecting cyanobacteria from the Lake and a support letter from Mr. Dan Levy (Vice president, AECOM) is attached along with this proposal. Cyanobacterial scums will be collected using ‘float it up and skim it off’(micro-flotation) technique. An overview of cyanobacteria collection, processing, storage, field application, and extension outreach is presented in Figure 3. Detailed description of collection and processing are discussed below:

1.Cyanobacteria collection (AECOM) and processing:

The AECOM will deploy a custom-built, mobile algae harvesting unit (Figure 4) that separates algae biomass from water. Even a small-scale harvester can process between 100-175 gallons per minute and produces up to 1,000 gallons of algae biomass in 8 hours. Skimmers will capture thick mats of algae floating on the water’s surface. Collected algae biomass slurry will be dewatered to produce semi-solid mats. Composite cyanobacterial mats will be collected from various locations of the Lake and adjacent river area. Collected cyanobacteria mats will be transported to FIU greenhouse for drying and processing. Dried and ground (in powder form) cyanobacteria biofertilizer will be stored in colored plastic bags for field application. Storage of the dried cyanobacteria biofertilizer in colored plastic bags can increase its shelf life (Jha and Prasad, 2006). In this phase we will invite our agroecology students to experience cyanobacteria collection and processing for biofertilizer preparation.

A preliminary study was conducted by our research team where we (a) collected cyanobacteria samples (mats; n = 8) from Lake Okeechobee, (b) dried those samples at 450C for 72 hours, and (c) ground those dried samples using mortar and pestle (Figure 5A). Commercial grinding machine (Model# BL-230) will be used to process the biofertilizer required for greenhouse study and field trials.

We found the dry matter content of the cyanobacterial mat was 17 to 19%.

UPDATE - Annual report (2022)

Cyanobacteria collection and processing

Figure 2022-1 Figure 2022-2 Figure 2022-3

As we mentioned in our statement of work (SOW), we communicated several times with the AECOM company, who helped us collecting the cyanobacteria from Lake Jesup (28043’N, 81013’W) located in Central Florida. We also visited the floating cyanobacteria collection station of AECOM company (Figure 2022-1) and learned more about the working principles of the unit. The custom-built, mobile algae harvesting unit of AECOM was separating algae biomass from the lake Jesup water. Generally, a small-scale harvester can process between 100-175 gallons per minute and produces up to 1,000 gallons of algae biomass in 8 hours. Cyanobacterial slurries were collected using ‘float it up and skim it off’(micro-flotation) technique and later coagulated in the unit. Cyanobacterial slurry was collected in five-gallon buckets (Figure 2022-2) for easy transporting and brought back to the FIU campus for further processing. One small glass jar of sample was brought in ice cooler and stored at -200C at FIU laboratory for microcystin analysis. This sample will give us the microcystin concentration of the cyanobacteria sample immediately after harvesting from the lake. At FIU campus, the rest of the slurry was then air dried (after spreading on large plastic trays) in the greenhouse for 3 to 4 weeks (Figure 2022-3) to obtain dried cyanobacteria materials. Slurry on the plastic trays were stirred up occasionally to expedite the drying process. Dried cyanobacteria then powdered using a mechanical grinder and stored in colored plastic bags for future applications.

Update 2024 - Scaled cyanobacteria processing approach for field trials

To prepare for our field trials, we sought a means to dry the remaining 200 gal ( 757 L) of cyanobacteria slurry collected from Lake Jesop on a larger scale. We arranged a shallow pool of approximately 2.4m x 4.6m x 0.3m) long using standard cinder blocks. The blocks were lined with a plastic pond liner to keep slurry from leaking. The entire pool was placed beneath a high tunnel with an impermeable cover to prevent rain from entering the pool (Figure 2024-1A). Approximately 100 gal (378 L) were added per drying batch, keeping the slurry level at about 4 cm high. After about 2 weeks, the slurry is dry enough for collection and has lost about 80% of it’s mass from water evaporation. At that point the remaining slurry is easier to condense and collect. We dried the remaining cyanobacteria in an oven overnight at 70°C to dry off any remaining moisture. Dried cyanobacteria was then grinded in a designated blender to process into a fine biofertilizer powder. We were able to transform the aproximate 200 gal of slurry into 15.9 Kg of biofertilizer powder ready to be applied to fields.

2. Timeline development for safe use of the biofertilizer:

This project also aims to develop the timeline for safe use of the cyanobacteria biofertilizer produced in the field for crop production. As commented by one of the reviewers about the safety concern of the biofertilizer, we will measure the microcystin, a common cyanotoxin found in cyanobacteria during first project year.

Microcystin content of cyanobacteria will be measured following the USEPA method 546 (ADDA- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay technique) from collection time (T0) till 50 days after collection (T50) at 10 days interval to develop a decay rate curve (Birbeck et al., 2019). Krishnaswamy Jayachandran (Co-PI of this project) and colleagues conducted an experiment on cyanobacteria samples collected from Lake Okeechobee to measure microcystin degradation over time (Ramani et al., 2012). They found that more than 75% of the cyanobacteria microcystin degraded within 3-weeks after harvesting from the Lake. Cyanobacteria powder do not cause airborne problems or human health issues. However, we will take proper pre-cautions (gloves, masks) during biofertilizer processing and field application.

We will conduct safety training and knowledge dissemination workshops for growers and the farm workers for safe and better handling of the biofertilizer.

3.Objective # 1: Nutrient and chemical analyses of cyanobacteria biofertilizer

Subsamples of cyanobacteria biofertilizer will be analyzed at the FIU Soil-Plant Microbiology Laboratory for nutrient (macro and micro) contents and other chemical properties including OM content, pH, and cation exchange capacity (CEC). The pH of the biofertilizer will be measured in 2:1 (water: biofertilizer) slurry using ‘Denver Instrument’ pH meter. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the biofertilizer will be measured by sodium acetate extraction following method USEPA 9081. A subsample of cyanobacteria will be combusted in 6000C for 6 hours in Fisher Scientific isotemp muffle furnace to obtain organic matter content of the biofertilizer. Total C and N contents will be analyzed in a Thermo-Scientific Flash EA (Dumas combustion method). For multi-element analysis (macro and micro elements), pre-weighed cyanobacteria samples will be combusted at 550°C and then extracted using concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl). The extracted samples will be analyzed in ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Optima 8300). Total P will be extracted by combusting samples in the presence of MgSO4 at 550°C and solubilizing the ash with 0.6 N HCl to convert all P to ortho-P forms followed by colorimetric analysis (antimony-phospho-molybdate complex) in TechniconTM AutoanalyzerTM Sampler IV.

Agroecology graduate students and student interns will be involved to gain experimental and experiential learning about chemical analyses of cyanobacteria biofertilizer in the laboratory.

Preliminary results (fertilizer grade): Physicochemical parameters of processed cyanobacteria biofertilizer samples were analyzed at the extension soil testing laboratory of the University of Florida (Table 1).

Table 1. Nutritional properties of cyanobacteria biofertilizer used for pilot experiment. Values are presented as mean ± SD of n = 8 samples.

|

Parameters |

Unit |

Value |

|

Total C (TC) |

% |

19.56 ± 0.71 |

|

Total N (TN) |

% |

1.79 ± 0.07 |

|

Total P (TP) |

% |

0.02 ± 0.00 |

|

Total S (TS) |

% |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

|

Potassium (K) |

% |

0.06 ± 0.01 |

|

Calcium (Ca) |

% |

22.12 ± 0.20 |

|

Magnesium (Mg) |

% |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

|

Iron (Fe) |

ppm |

2005 ± 160 |

|

Manganese (Mn) |

ppm |

132.56 ± 13.35 |

|

Zinc (Zn) |

ppm |

53.34 ± 0.69 |

|

Copper (Cu) |

ppm |

29.51 ± 4.80 |

|

Boron (B) |

ppm |

95.37 ± 4.21 |

|

Molybdenum (Mo) |

ppm |

1.82 ± 1.01 |

|

Nickel (Ni) |

ppm |

4.34 ± 1.78 |

The C:N ratio (mol:mol) of test cyanobacteria biofertilizer averaged 12.7:1, lower than other organic nutrient sources. Therefore, we expect increased N mineralization in soil when cyanobacteria biofertilizer is applied. Another important component was Fe content (average 2005 ppm) in our biofertilizer mix. South Florida soils generally lack Fe because of low SOM content, high temperature, and high soil pH (Ozores-Hampton, 2013). Vegetable farmers often face problems due to Fe deficiency in these soils (Liu et al., 2012). Our collaborative growers informed us of the need to apply chelated Fe (an expensive option) to meet the crop requirements. Thus, cyanobacteria biofertilizer would serve as an excellent source of Fe and other micronutrients. Visual observation from preliminary experiments indicate that the interveinal chlorosis of young okra leaves in control plots possibly resulted from Fe deficiency (Figure 5B). Leaf samples were collected and submitted for micronutrient analyses (analysis in progress at the time of this proposal submission).

Typical N% for commonly used organic fertilizers in South Florida such as poultry manure is 1.5 to 2.3% (Hochmuth et al., 2009). Our test cyanobacterial biofertilizer falls within this range. However, cyanobacteria biofertilizer provides micronutrients and offer ecosystem services which makes it a high potential biofertilizer for vegetable production.

4.Greenhouse experiment at FIU:

Greenhouse experiment will be conducted during first project year (2021-2022) to evaluate the effect of cyanobacteria biofertilizer on crop growth and soil properties (pH, EC, total P, total N, total C content, OM content, aggregate stability, and nutrient loss). Representative South Florida soils will be collected from LNB groves farm, Homestead, FL (courtesy of Mr. Marc Ellenby, our collaborative grower) for this greenhouse study. Seven-gallon and five-gallon pots will be used to grow tomato (Lycopersicum spp variety: BHN 975) and okra (Abelmoschus esculentus variety: Cajun Delight), respectively. These tomato and okra varieties perform well in Florida’s climate and are highly resistant to insect pests and were selected after discussing with Dr. Qingren Wang (extension specialist for commercial vegetables; our team member) and Mr. Marc Ellenby. Fertilizer application rates will be 224 kg N ha-1, 112 kg P2O5 ha-1, and 168 kg K2O ha-1 for tomato, and 135 kg N ha-1, 112 kg P2O5 ha-1, and 112 kg K2O ha-1 for okra. Biofertilizers will be applied along with synthetic fertilizers in different combinations. Seven treatments combinations [T0: control (no fertilizer applied); T1: 100% biofertilizer; T2: 75% biofertilizer + 25% synthetic; T3: 50% biofertilizer + 50% synthetic; T4: 25% biofertilizer + 75 % synthetic; T5: only 50% synthetic fertilizer and no biofertilizer; and T6: 100% synthetic fertilizer] will be assigned in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with 20 replications (5 main plot x 4 within plot = 20) per treatment.

Because of the highly reactive nature of N fertilizers and the porous sandy soils of Florida, the N fertilizer will be applied in two splits. Urea (H2N-CO-NH2; 46-0-0) will be used as the primary source of inorganic N. Triple super phosphate [Ca(H2PO4)2. H2O; 0-45-0] and muriate of potash (KCl; 0-0-62) will be used as inorganic source of P and K, respectively. We will conduct demonstration training on shade house experiments to the local farmers and students during organic farming workshops and field days.

Preliminary results (pot experiment): We arranged the pot experiment in RCBD at FIU shade house using 2-gallon pots for each plant. Four treatments (with six replications for each treatment) used in this study including control (no fertilizer), full synthetic N fertilizer (urea; 46-0-0), full cyanobacteria biofertilizer, and 50% synthetic + 50% cyanobacteria biofertilizer. Soils were collected from LNB Grove Farm, Homestead, FL (website: https://www.lnbgrovestand.com/).

Table 2. Effect of cyanobacteria biofertilizer on plant height, stem diameter, and leaf chlorophyll content (SPAD readings) of okra. Like letters (lowercase) indicate not significant at α = 0.05 level (SAS 9.4 was used)

|

Treatment |

Week 4 |

Week 7 |

||||

|

Plant height (cm) |

Stem diameter (mm) |

SPAD* |

Plant height (cm) |

Stem diameter (mm) |

SPAD |

|

|

n = |

6 |

6 x 3 =18 |

6 x 6 = 36 |

6 |

6 x 3 =18 |

6 x 6 = 36 |

|

Control |

34 ± 6 a |

6.1 ± 0.6 b |

31 ± 6 a |

48 ± 6 b |

7.4 ± 0.7 b |

34 ± 5 b |

|

Full synthetic |

47 ± 9 a |

8.4 ± 0.9 a |

43 ± 8 a |

67 ± 9 a |

10.8 ± 0.9 a |

49 ± 8 a |

|

50-50 Fertilizer |

44 ± 6 a |

8.7 ± 0.9 a |

42 ± 6 a |

64 ± 9 a |

10.5 ± 1.1 a |

49 ± 7 a |

|

Full cyanobacteria |

45 ± 5 a |

9.2 ± 0.8 a |

45 ± 7 a |

69 ± 12 a |

11.2 ± 1.1 a |

51 ± 8 a |

* SPAD: Soil Plant Analytical Development represents chlorophyll contents of the leaves (no unit)

Overall, plant height (69 cm) and SPAD (51) readings at week-seven were significantly (P<0.05) higher in full biofertilizer treatment than unfertilized control. Stem diameter (9.2 and 11.2 mm at week 4 and week 7, respectively) was always significantly higher in fertilizer treatments than control (Table 2). However, no significant differences were found between fertilizers, indicating that cyanobacteria biofertilizer can achieve same crop physiological parameters as synthetic fertilizers.

UPDATE - Annual Report (2022)

Experimental set up in the greenhouse

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Var: Cajun Delight) and tomato (Lycopersicum spp Var: BHN 975) crops are growing at three- and five-gallon plastic pots, respectively, at FIU greenhouse. Plastic pots were filled up with soils collected from Homestead area of South Florida. Physicochemical properties of the background soil are presented in Table 2022-1. Okra and tomato pots were organized in separate bench tops with each pot was spaced about 3 ft from each other. Walking rows are available between each bench tops for watering the plants, regular maintenance, and recording the experimental data. Biofertilizer was applied along with synthetic fertilizers in different combinations. Seven treatment combinations were a) T0: control (no fertilizer applied); b) T1: 100% biofertilizer; c) T2: 75% biofertilizer + 25% synthetic; d) T3: 50% biofertilizer + 50% synthetic; e) T4: 25% biofertilizer + 75 % synthetic; f) T5: only 50% synthetic fertilizer and no biofertilizer; and g) T6: 100% synthetic fertilizer. The experimental set up followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with five replications for each treatment. At this point fruit setting just started for both okra and tomato. Okra seeds were planted in January 2022. We grew tomato seedlings in nursery trays from December, 2021 to January, 2022. One month tomato seedlings were then transplanted in the pots in 3rd week of January, 2022. Both okra and tomato plants were watered in regular intervals in the greenhouse.

Table 2022-1. Physicochemical properties of the soils collected from the field and used to fill up the pots in the greenhouse

|

Parameters |

Unit |

Value |

|

pH (1:1 soil slurry) |

|

7.06 ± 0.33 |

|

TN |

% |

0.74 + 0.08 |

|

TC |

% |

14.39 ± 0.98 |

|

Ca |

% |

1.51 ± 0.026 |

|

Cu |

% |

0.0003 ± 0.00001 |

|

Mg |

% |

0.033 ± 0.0008 |

|

P |

% |

0.002 ± 0.00006 |

|

K |

% |

0.014 ± 0.0004 |

|

Na |

% |

0.014 ± 0.0012 |

|

S |

% |

0.022 ± 0.00009 |

|

Zn |

% |

0.001 ± 0.00009 |

5.Objective # 2: Efficacy of cyanobacteria biofertilizers (crop yield and soil health) in field settings

Agricultural field plots from our collaborative growers will be used to test the effect of cyanobacteria biofertilizer on tomato and okra production and soil health analysis. Physicochemical analysis of background soil will be analyzed before conducting the experiment. Yield parameters (shoot weight, root weight, plant height, and fruit yield) and compositional analyses (leaf chlorophyll content, plant height, plant shoot diameter, and nutrient uptake) of tomato and okra will be recorded during plant growth stages (early transplanting/seeding stage, flowering, early fruit set/pod-filling) and at harvesting. The yield parameters for our study were selected after discussing with Mr. Robert Barnum and Mr. Marc Ellenby. Routine physicochemical parameters (pH, EC, TP, TN, TC, POM, biomass C, N and P, Mehlich-3 extractable plant essential nutrients, ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, OM%, water filled pore space WFPS%, and aggregate stability) of soil samples will be analyzed in regular intervals throughout crop production. Soil pH will be measured in 1:1 soil to water slurry. Soil EC would be measured using Oakton conductivity meter. Analysis of TC, TN, and TP content will follow methods discussed earlier for soil samples. Particulate organic matter (POM) is a powerful indicator of soil health and quality (Chan, 2001; Wilson et al. 2001). Particulate organic matter (POM) will be measured in dry soil using a method described by Nciizah and Wakindiki, 2012 and will be calculated using the formula:

POM g/g dry soil= [(Dry soil weight - Combusted soil weight)/(Dry soil weight)] x 100

Soil aggregate stability will be measured using dry and wet sieving techniques (Kemper and Rosenau, 1986). Water soluble aggregates (WSA) is generally determined using:

WSA = {(Wac - Wc) / Wf}*100

Where, WSA (%) is the water-soluble aggregate in particular class or range of aggregate class, Wac (gm) id the dry weight of aggregates and coarse material; Wc is the dry weight of coarse material and Wf is the dry weight of the soil under each fraction of aggregate class.

Paid student (assistantships/scholarships) will assist in sample analysis where they will gain knowledge about sustainable agricultural research projects.

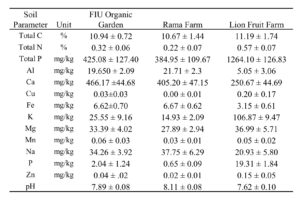

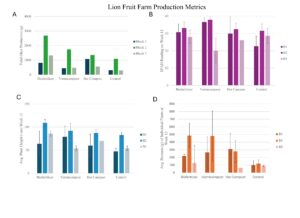

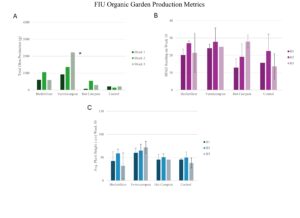

UPDATE 2024- Field Trial Experimental Design

Field trials for okra (Abelmoschus esculentus; variety Clemson Spineless) production were conducted across three South Florida farm locations: FIU Organic Garden (Sweetwater, FL), Rama Farm (Homestead, FL), and Lion Fruit Farm (Homestead, FL). Each location provided approximately 30 m² of farm area for the trial setup. Soil samples were collected from each plot at all three farms, and sent to the UF/IFAS Analytical Services Laboratories in Gainesville,FL. The physicochemical properties of the baseline soil are summarized in Table 2024-1.

Table 2024-1. Soil properties of each farm site collected from all plots on Day 0. N=12

The trial area at each farm was divided into 12 plots, each measuring approximately 0.7 m x 3 m. Fourteen okra plants were planted per plot, spaced 23 cm apart. Four experimental treatments were tested: (a) control (C; no fertilizer applied), (b) biofertilizer (B), (c) vermicompost (V), and (d) standard hot compost (H). Treatments were assigned using a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with each treatment replicated across 3 plots.

The vermicompost was sourced from Lion Fruit Farm, the standard hot compost from Fertile Earth Farms, and the biofertilizer was prepared using cyanobacteria collected and processed according to previously outlined procedures.

Recommended nutrient doses for okra production are 135 kg N ha⁻¹ and 112 kg K₂O ha⁻¹. Fertilizer application rates for each treatment were calculated based on the nutrient composition (N) of each fertilizer, as analyzed by the LECO Carbon Nitrogen Analyzer. The organic fertilizer composition percentages and the calculated fertilizer amounts applied per plot are detailed in Table 2024-2. UF/IFAS Analytical Services Laboratories in Gainesville,FL analyzed all parameters except Total N and C.

Table 2024-2. Physicochemical properties of all three compost treatments. Calculated N percentage values were used to determine needed compost quantities to achieve an application rate of 135 kg N ha⁻¹ per plot. All analyses had an n=3.

Okra seeds were germinated in the FIU Shadehouse and transplanted into field plots on June 6, 2024. Plants were monitored biweekly for 12 weeks, measuring SPAD values and plant height. Once fruiting began, okra pods were harvested weekly and weighed to track total production. At the end of the 12-week period, three randomly selected plants from each plot were harvested, measured, and weighed for individual biomass. Biomass samples from each plot were subsequently analyzed for total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and other essential nutrients. Soil samples were also collected from each plot at the end of the trial to compare with the baseline soil samples collected at the trial’s initiation.

6.Objective # 5: Economic assessment of biofertilizer application

We assume that if farmers were to adopt the new biofertilizer, they would experience the following types of changes and/or opportunity costs: (a) changes (increase or decrease) in the annual costs of cultivation; (b) changes in crop yields (increase or decrease) and products sold; and (c) change in product market price (due to product quality changes). Therefore, the “true” or “incremental” benefits of integrating the proposed biofertilizer will be equal to the difference in the net profits between with and without implementation. The following methodology captures the economic effects of all the above three factors on the incremental benefits of applying new fertilizer. Assume that the per acre cost of crop production is c ($/ac). Per acre crop yield is y (lb/ac) and market price is p ($/lb). Let π ($/ac) denote the net profit. Subscripts pre and pos denote before and after implementation.

The expected net profit (πpre) before the implementation of the new fertilizer is,

πpre = (ypre · ppre – cpre)

Similarly, the expected net profit after the implementation of a given N-I combination (πpro) is,

πpos = (ypos · ppos – cpos)

Note that both quantity and quality of the product could vary from the current to the new practice. The annual per acre incremental benefits of biofertilizer application (IB) is the difference in the net profit between without implementation and with implementation. Formally,

IB = πpos - πpre

Crop yield, costs, and price parameters used in the above economic model are stochastic in nature and may have certain underlying probability distributions. Based on the field and lab experimental trials (sample mean and standard deviation), we will construct appropriate probability distributions (e.g., normal distribution) for yield parameters. Historical market data (USDA) on prices and costs will be used to develop appropriate uniform or other probability distribution reflecting market uncertainty. Then, the incremental benefits (IB) will be estimated by running Monte Carlo simulations, which accounts for uncertainty in model parameter values (yields, costs, etc.) by expressing them as probability distributions rather than fixed values.

We will first need to gather the data for the economic enterprise budgets for existing tomato and okra crops in Florida. Using these as starting points, we will then develop mixed-crop budgets for alternative systems that involve tomatoes and okra production and seasons. The information on the output side of the budget (e.g., market price, season, product quality, value addition, etc.) will directly come from secondary sources such as USDA. Monte Carlo stochastic analysis will be conducted around each mixed-crop budget in order to capture the effects of multiple scenarios reflecting alternative market channels, degree of value addition, output and input price variances. The final recommendation will be based on alternative production scenarios of biofertilizers, crops, seasons, and others.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

UPDATE - Annual report (2022)

This year we collected cyanobacteria slurry samples every 12 days interval until 60 days after collection from the lake. The first sample collected immediately after cyanobacteria harvesting from the lake is noted as T0. All the slurry samples (T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5) for microcystin concentration were collected and stored in -20 deg C for analysis.

Figure 2022-4 Figure 2022-5 Figure 2022-6 Figure 2022-7

This year we are conducting the experiment in FIU greenhouse. Both okra and tomato plants are still growing and are in their fruiting stages at this point (Figure 2022-4, 2022-5). Basic physical properties during crop production such as plant height, stem diameter, leaf chlorophyll contents were collected in regular intervals. Plant height, stem diameter, and SPAD readings for tomato plants during flowering and fruit settings are presented in Table 2022-2. We will collect two more sets of plant physiological data before harvesting. Soil samples from each treatment (during fruit settings) were collected and processed (dried and ground) for future analysis. Additional soil sample from each treatment will be collected during harvesting. Those data will be added to the progress report once the analyses are done.

Our results (as the data collected so far) from tomato experiment clearly indicate that 100% cyanobacteria biofertilizer (T1) applied plots performed better than control plots. Average plant height (92.71 cm), stem diameter (8.47 mm), and SPAD readings (47.09) of T1 was 22%, 15%, and 20% higher, respectively, than control plots. When we compared the plant parameters of T1 with 100% synthetic fertilizer applied plots (T6), no significant differences were found. Therefore, it can be noted that 100% cyanobacteria fertilizer application is performing similar to 100% synthetic fertilizer application at this point of data collection. However, better comparative analysis can be made once we will have more plant parameters and yield data available after harvesting.

Table 2022-2. Physiological parameters of tomato plants during different growth stages

|

Treatments |

Plant height (cm) |

Stem diameter (mm) |

SPAD reading |

|

Flowering Stage |

|||

|

T0 |

73.66 |

6.95 |

37.78 |

|

T1 |

83.82 |

7.95 |

43.16 |

|

T2 |

79.59 |

7.66 |

44.47 |

|

T3 |

80.43 |

7.38 |

42.75 |

|

T4 |

82.97 |

7.77 |

44.36 |

|

T5 |

75.35 |

6.87 |

40.14 |

|

T6 |

86.36 |

7.52 |

43.04 |

|

Fruit Setting |

|||

|

T0 |

78.55 |

7.79 |

40.55 |

|

T1 |

101.60 |

8.99 |

51.01 |

|

T2 |

96.52 |

8.42 |

49.03 |

|

T3 |

94.05 |

8.14 |

46.70 |

|

T4 |

99.91 |

8.59 |

46.20 |

|

T5 |

82.55 |

7.94 |

42.84 |

|

T6 |

107.02 |

8.38 |

48.99 |

Common issues during production

A major problem occurred during the greenhouse experiment was unexpected cooler temperature in South Florida during January, 2022. Growth of both okra and tomato plants were little slower because of the lower temperature. In general, both okra and tomato can be harvested at 65 to 70 days and 90 to 100 days, respectively. However, harvesting of our okra and tomato plants will take little longer than their usual harvesting schedule. Control plots for both okra and tomato plants showed possible Fe deficiency (interveinal chlorosis; Figure 2022-6). We also found some fungal disease (possibly Septoria leaf spots) in our tomato plants (Figure 2022-7). We applied copper fungicide to control fungal spots in tomato plants. Visually at least 60 to 70% of the leaf spots were controlled by using copper fungicide. We collected and processed (dried and ground) plants leaf samples during different growth stages (flowering and fruit settings), however, the laboratory analysis of nutritional properties of those samples is scheduled to be done.

Project timeline for 2021 to 2022

|

Activities |

Time frame |

Job status |

Additional comments |

|

1. Project notification |

February, 2021 |

Done |

|

|

2. Project account set up |

November, 2021 |

Done |

|

|

3. Cyanobacteria collection and processing |

|

|

About 2 to 3% dry matter was present in the slurry |

|

Trip to lake Jesup for cyano collection |

November, 2021 |

Done |

|

|

Taking raw samples for microcystin analysis |

November, 2021 to January, 2022 |

Done |

Samples were preserved at -200C for further analysis |

|

Drying cyano samples in plastic trays |

November, 2021 to January, 2022 |

Done |

|

|

Grind samples to make biofertilizer |

January, 2022 |

Done |

|

|

4. Setting up tomato and okra experiment |

|

|

At FIU greenhouse |

|

Soil samples collected and pots were prepared for greenhouse study |

January, 2022 |

Done |

|

|

Fertilizer application in the pots |

January, 2022 |

Done |

|

|

5. Data collection |

|

|

|

|

Plant height, stem diameter, and SPAD |

February to April, 2022 |

Continued |

More samples will be collected |

|

Soil samples collection during different growth stages |

February to April, 2022 |

Continued |

Few sets were collected, more will be collected |

|

Plant tissue sampling - at flowering stage - at fruit settings - at harvesting |

February, 2022 March, 2022 April, 2022 |

Done Done Scheduled |

|

|

5. Microcystin analysis |

April, 2022 |

Scheduled |

|

|

6. Harvesting |

April, 2022 |

Scheduled |

|

|

7. Laboratory analysis |

From April, 2022 |

Scheduled |

|

|

8. Project update at the SARE portal |

May, 2022 |

Scheduled |

|

******Update (2024)- The final results from this greenhouse trial have been published (2024) in the article titled "The Application of Cyanobacteria as a Biofertilizer for Okra Production with a Focus on Environmental and Ecological Sustainability" by Chanda et al in the Journal: Environments (https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11030045).*****

UPDATES 2024- Results from field trials

Field trials were conducted for 12 weeks during the summer of 2024, from June 6th to August 29th. Weather station KFLMIAMI985 in Homestead, FL, recorded temperatures ranging from 23.2°C to 37.7°C, with an average of 28.2°C and a total rainfall of 38.6 cm over the study period (www.wunderground.com). Throughout the trial, student assistants, including 2 REU undergraduate students, 3 high school interns, and several additional volunteers, contributed to plant monitoring and data collection. Each farm’s experimental layout included three blocks (B1, B2, B3), with each block containing one plot per treatment—Vermicompost (V), Biofertilizer (B), Hot Compost (H), and Control (C)—ensuring consistent comparisons across treatments.

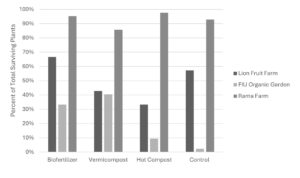

Production Challenges

Irrigation was inconsistent at both Lion Fruit Farms and the FIU Organic Garden, impacting plant health. The FIU site was particularly affected due to its limited summer shade. Additionally, army worms were observed at both FIU and Lion Fruit Farm sites, adding to plant stress. Root assessments conducted at the end of the trial further revealed substantial nematode impact at Lion Fruit Farms, likely contributing to higher plant mortality. Survival rates at Rama Farm were markedly higher (86-98%) compared to Lion Fruit Farm (33-67%) and FIU (2-40%), as shown in Figure 2024-2.

Figure 2024-2. Percent of Total Surviving Individual Plants per treatment at each site. Survival percentages were calculated by dividing the number of surviving plants in each treatment by the initial total planted count of 42 (14 plants per plot, 3 plots per treatment).

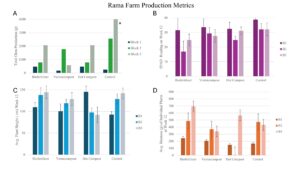

Results at Rama Farm

Block Effects

At Rama Farm, variations in sunlight exposure across blocks were observed, with Block 1 (B1) receiving significantly less light than Blocks 2 (B2) and 3 (B3). This reduced light exposure likely impacted growth in B1, as plants in this block consistently exhibited shorter heights across all treatments at week 12. Specifically, all plants in B1 were significantly shorter than those in B2 and B3 for all treatments. Despite these height differences, biomass weights based on three plants per plot and total okra production (g) did not show significant differences between blocks. Additionally, SPAD readings were consistent across blocks, indicating that while light reduction affected plant height in B1, it did not substantially impact overall plant health.

Treatment Effects

Outliers were identified and excluded using the interquartile range (IQR) method. After removing these outliers, analysis of average okra production across treatments showed that the control produced the highest yield, followed by biofertilizer, vermicompost, and hot compost. However, these differences in yield were not statistically significant. In terms of individual biomass, no significant differences were detected across treatments, though biofertilizer consistently demonstrated higher biomass values within the same blocks.

For plant heights at week 12, significant differences were observed between treatments. The biofertilizer treatment resulted in significantly taller plants than both hot compost and control, with no significant difference between biofertilizer and vermicompost. Biofertilizer and vermicompost treatments, therefore, led to greater plant heights compared to control and hot compost.

Results at Lion Fruit Farm

Block Effects

At Lion Fruit Farm, light levels were significantly higher in B2, which may have contributed to observed differences in growth metrics across blocks. SPAD readings for all treatments did not differ significantly between blocks, indicating consistent leaf chlorophyll levels across the field. However, plant heights measured at week 12 showed that B2 had significantly taller plants than B1, but not B3. Individual biomass weights also varied across blocks, with B2 yielding significantly higher biomass than B1. In terms of total okra harvest, B2 statistically outperformed B1 and B3,. These findings suggest that B2 consistently supported higher growth and yield across multiple metrics, likely due to its elevated light levels.

Treatment Effects

Analysis of average okra production across treatments, after excluding outliers, showed that biofertilizer treatment yielded the most okra, followed by vermicompost, hot compost, and control. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Individual biomass weights were also comparable across treatments, with both biofertilizer and vermicompost treatments showing similar biomass levels in each block.

SPAD readings between treatments showed no significant differences, indicating similar chlorophyll content across treatments. For plant heights at week 12, the biofertilizer treatment led to significantly taller plants compared to control and hot compost, indicating a stronger effect on growth. There was no significant difference between biofertilizer and vermicompost in plant height.

These findings suggest that both biofertilizer and vermicompost are effective organic fertilizers, showing comparable impacts on plant growth metrics such as height and biomass production.

FIU Organic Garden Results

Block Effects:

At FIU, despite challenges from inconsistent irrigation, high sun exposure, and pest pressures previously noted, no significant differences were observed in okra production, SPAD readings, or plant heights across blocks within each treatment. This suggests that block orientation and minor environmental variations between blocks did not substantially impact growth outcomes at this site.

Treatment Effects:

Vermicompost yielded the highest okra production among treatments, significantly outperforming Hot Compost and Control , but not Biofertilizer. SPAD readings, which reflect plant health through chlorophyll content, showed no statistical difference between treatments. However, plant heights measured at week 10 indicated that Vermicompost supported significantly taller plants than the Biofertilizer, Control, and Hot Compost treatments. These findings highlight the resilience of Vermicompost and Biofertilizer as organic treatments in challenging conditions. Vermicompost demonstrated particular efficacy in promoting plant height and yield under water stress and pest pressure, while Biofertilizer remained competitive, suggesting it as a viable alternative organic fertilizer.

Field Trial Conclusions

The results across all three sites—Rama, Lion Fruit, and FIU—consistently demonstrated the benefits of Vermicompost and Biofertilizer treatments for promoting plant height and resilience under varying environmental conditions. While Vermicompost generally yielded the highest okra production, significantly outperforming Hot Compost and Control at FIU, Biofertilizer matched Vermicompost in both production and plant height at Lion Fruit and Rama farms, where it often performed significantly better than Control and Hot Compost.

Across sites, SPAD readings remained statistically similar across all treatments, indicating comparable levels of chlorophyll content and general plant health. However, when assessing plant height, Vermicompost and Biofertilizer stood out, particularly at FIU, where Vermicompost led to significantly taller plants in week 10, even under challenging conditions with limited irrigation and pest pressures. Biofertilizer’s consistent performance in plant height across Lion Fruit and Rama farms, often on par with or surpassing Vermicompost, further highlights its potential as a viable alternative organic fertilizer.

The findings suggest that while Vermicompost may have a slight edge in promoting growth metrics like plant height and yield under extreme conditions, Biofertilizer is competitive in its effectiveness. Both Vermicompost and Biofertilizer show promise as resilient organic amendments, providing consistent support for plant growth and crop yield across diverse farm environments. These treatments offer sustainable options for enhancing productivity in organic agriculture, especially in environments with limited water resources and pest challenges.

Additional results from Summer 2023 mini-field trial on tomatoes are included in this link: Different treatments on tomato production

Next Steps

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of these treatments, further analyses are planned. The soil samples collected on the final day of the trial will be compared to baseline samples from the first day to assess long-term effects of Vermicompost and Biofertilizer on soil nutrient dynamics, structure, and overall health. Additionally, with the production data gathered, an economic analysis will be conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of each treatment. Since the final field trials concluded less than two months before the due date of this report, these analyses are still in progress and will be included in a forthcoming publication.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Support_Letter_DiMare Support letter_Dr. Wang Support letter_Dr. Li

Outreach and dissemination

Florida International University (FIU) Agroecology Program sponsors and participates in several outreach programs and events to disseminate newly acquired knowledge about sustainable agricultural practices. This year we have Dr. Qingren Wang, an extension specialist for commercial vegetables. He will be our team leader for extension and outreach activities for this project.

|

Outreach program |

When |

Audience |

Activities |

|

South Florida Regional Science and Engineering Fair |

January every year |

Middle and high school students |

Conduct roundtable discussion on biofertilizers and sustainable agriculture |

|

Compost workshop |

Fall and Spring per year |

Agroecology Program students and other students, faculty, beginning farmers |

Discussion on organic agriculture, biofertilizer, sustainable agriculture |

|

Agroecology Annual Symposium |

March every year |

Undergraduate and graduate students from FIU, St. Thomas University, Miami Dade College, Faculty |

Undergraduate and Graduate Poster and Oral presentations on Biofertilizer project progress |

|

CASE Take Our Kid to Work Day |

April every year |

Elementary, middle, high school students |

Laboratory and shade house tour of biofertilizer experiments |

|

Organic Gardens in Sustainable Food Systems Workshop |

Fall and Spring in each year |

Students and Farmers |

Demonstrate biofertilizer production, nutrient analysis, sustainable agriculture |

|

Farm Hop Tour |

November in every year |

Agroecology Program students |

Tour of collaborating farmers field to visit biofertilizer tomato and okra field experiments |

Other Outreach/Extension/Dissemination Activities

a) Local news, news articles and websites

Cyanobacteria blooms have been a major concern in Central and South Florida. Several news channels such as CBS local, The Weather Channel, NPR have been regularly reporting news about HABs and their consequences on human health and aquatic lives. Our collaboration with the international company AECOM and US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to physically remove the cyanobacteria from the Lake Okeechobee water will be covered by local news channels. Most of the people living around the Lake are concerned about water contamination from microcystin, foul smell of cyanobacteria, and economic decline value of their property. Their urgent need to find a better solution to remove and discard HABs have been featured in several local news channels and newspapers (such as TC Palm). To our knowledge, no field-based research on cyanobacteria biofertilizer has been conducted in the US. An innovative approach of using this nuisance cyanobacteria scum for sustainable farming and better community service is expected to draw attention of local people. We are planning to highlight our work in local new channels to educate public about recycling renewable resources, organic farming, soil health, carbon sequestration, and over all sustainable living. Agroecology Program website and Southern SARE website will be included in the news, so that interested people can direct their questions and concerns to us. Our Agroecology webpage ‘Biofertilizer: A sustainable nutrient source’ will provide information about this project to students, faculty, farmers, and general public. This project provides a unique approach to increase overall environmental sustainability on integrated farming system.

b) Workshops, field days, and training sessions

Florida International University (FIU) Agroecology Program organize several symposia and professional workshops throughout the year. FIU is in the process of acquiring a 40-acre organic farm (called Possum Trot) through gift, which attracts a large number of farmers, residents and schoolchildren for eco-tour and experiential learning. In addition, under a grant from the USDA Office of Advocacy and Outreach, we have been conducting bi-weekly technical and managerial workshops and four-month long farm apprenticeship for Beginning Farmers, Veterans and Socially Disadvantaged (BVSD) farmers on this and other private farms in South Florida. More than 20-25 participants take part in each workshop from Southeast Florida. For the last twelve years, we have been conducting annual Agroecology Symposium under various USDA NIFA grants program. More than 200 people including farmers and industry people attend the symposium. We also conduct annual International Agroecology Workshop. Under the proposed project, we will invite organic growers each year to participate in a special workshop as part of the annual Agroecology Symposium to discuss project results and gather dissemination ideas, feedbacks on our research activity and identify gaps for effective outreach activities. The workshop will also invite USDA, UF and FIU scientists. One or more technical workshops we conduct for the farmers will focus on biofertilizer and sustainable agriculture. As part of the annual farm tour to be conducted by Miami Dade Farm Bureau and county Extension Office, we will invite farmers and other interest groups to take the tour of the ‘Possum Trot’ farm which houses already more than 350 tropical plant species. We have developed extensive network with Homestead area and other South Florida farmers and nursery owners. An important outreach activity will be our involvement with DiMare company (one of the largest tomato growers in the US). Mr. Tony DiMare (Vice president of DiMare company) has agreed to collaborate with us during sustainable agriculture demonstration through various workshops, field days, and training sessions in his farms. A support letter from Mr. DiMare is attached with this proposal.

c) Regular Meetings with local growers

We plan to conduct regular meetings with local farmers, growers, nursery owners, and stakeholders to discuss about the beneficial effects of low-cost biofertilizer and the economic benefits of replacing industrial synthetic fertilizer. Our collaborative growers team has decades of experiences in sustainable agricultural farming systems, and their valuable inputs during interactions with local growers will be a key factor to the proposed outreach/extension and dissemination activities. Our NGO partner Colonel John Mills (CEO of Redland Ahead Inc.) is the primary contact to reach out to veteran farmers and other small farmers. Colonel Mills operates a 20-acre community-based farm known as Verde Farm. Based on the successful execution of field pilot studies, biofertilizer application will be part of the farm operations in Verde Farm.

d) Incorporation in classroom teaching

We have series agriculture sciences courses offered in classroom on regular basis. Some of the courses are agroecology, sustainable agriculture, soils and ecosystems, soil biology, modern crop production. We plan on incorporating cyanobacterial biofertilizer – production, nutrient analysis, beneficial role in soil and crop production. Students gain both experiential and experimental knowledge on biofertilizers.

e) Annual conferences and peer-reviewed articles

We expect to generate valuable data from cyanobacteria collection, drying, nutrient analysis, green house studies, and field studies. We will have several extension articles and peer-reviewed scholarly publications. We also plan to present in annual conferences such as tri-society meetings (ASA-CSSA-SSSA) and regional farmers’ meet and more. Project reports will be submitted to SSARE based on the requirements. We will submit a final project report at the end of the third year.

F) Student involvement

Florida International University (FIU) Agroecology programs has 20 graduate, 75 undergraduate students, and 25 student interns. We continue to recruit students every year to our programs. We will involve students from cyanobacteria collection, processing, analysis, green house and field experiments. We encourage and mentor students to develop few hypotheses and design small experiments on biofertilizers. We have extensive experience mentoring students in such activities and proved successful. Students graduate from our program with biofertilizer experiential and experimental learning experience will serve as extension agents to disseminate the outcome of the project.

UPDATE Final Report 2024

Dattamudi_Southern ASA poster_Atlanta_2024

FIU-Symposium-Poster_Sri Madabushi_2022-1

REEU Presentation - REEU Presentation-1

Zamora_Subtropical poster_TX_2024 (YES grant)

Above are links to several undergraduate posters and presentations developed by student researchers conducting independent research regarding Cyanobacteria Biofertilizer trials. Research approaches were developed in collaboration with PI and Co-PIs as sub-topics to address the objectives proposed in this project. Several grants helped support this work including two Young Scholar Enhancement grants (2022 and2023) as well as an Research Experience for Undergrad (REU) grant with the FIU Agroecology program.

Published article:

Chanda et al., 2024_Application of cyanobacteria as a biofertilizer for okra production

Field trial publication in prep.

In the news:

https://news.fiu.edu/2024/water-pollutant-could-be-soil-savior

https://ambrook.com/research/environment/give-algal-blooms-a-chance

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge around biofertilizer was shared with collaborating farmers as well as farmer apprentices during workshops.

Project Outcomes

Project outcomes (2021-2022)

Webinar presentation:

Sanku Dattamudi, Saoli Chanda, Krishnaswamy Jayachandran, Leonard J Scinto, and Mahadev Bhat. Application of cyanobacteria as biofertilizer to increase vegetable production and soil health improvement in South Florida. July 27, 2021, Webinar, National Algae Association (NAA)

Manuscript:

Sanku Dattamudi, Saoli Chanda, Krishnaswamy Jayachandran, Leonard J. Scinto, and Mahadev Bhat. 2022. Use of cyanobacteria biofertilizer for okra production and improving agricultural sustainability in Florida, USA. Target journal: Agronomy. (In preparation)

Extension activities:

1. Undergraduate and graduate students of FIU Agroecology have been involved in this project. We demonstrated them biofertilizer preparation and its use for vegetable production.

2. Member of AECOM company visited our FIU greenhouse and the pilot study at FIU garden - where we showed them the current experiment and the applications of cyanobacteria biofertilizer

3. Pre-collegiate student visited our experiments to learn more about soil and plant sciences and agroecology.

4. We had couple of field visits to our collaborative growers where we described them about the project progress and scheduled timeline for next year field trial.

Update Final Report 11/14/24

Manuscripts:

Saoli Chanda, Sanku Dattamudi, Krishnaswamy Jayachandran , Leonard J. Scinto and Mahadev Bhat. (2024)..The Application of Cyanobacteria as a Biofertilizer for Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Production with a Focus on

Environmental and Ecological Sustainability. Environments. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11030045

Field trial publication in prep.

In the news:

https://news.fiu.edu/2024/water-pollutant-could-be-soil-savior

https://ambrook.com/research/environment/give-algal-blooms-a-chance

Extension activities:

1. FIU Farmer Outreach workshop conducted at the FIU Organic Garden on July 20,2024. "On-Farm Research Techniques: Experimenting with Recycled Algae as a Biofertilizer." Facilitated by Dr. Jazmin Locke-Rodriguez

2. Undergraduate and pre-collegiate interns who assisted in weekly field trial monitoring

3. Engaged in independent research with Highschool interns who had the opportunity to conduct their own trials with biofertilizer at the Miami Dade County Youth Fairgrounds.