Final report for LS21-356

Project Information

The principal investigator partners, North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers Land Loss Prevention Project (LLPP) and Rural Coalition (RC) coordinated the overall research and education planning, and administration of this SSARE project across the LLPP collaboration base and the RC’s membership, including cooperator groups (Operation Spring Plant, Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project, Inc., Rural Advancement Fund of the National Sharecroppers Fund, and Texas Coalition of Rural Landowners). During FY2021-2023, this entailed meeting with cooperators to pivot research and implementation approaches during the Pandemic and to consider emerging environmental, disaster, and federal program-related needs and opportunities (i.e., White House, Congressional and USDA programs ranging across HRSA, ARPA, IRA, DFAP, ERP and others).

Our findings related to heirs property, land acquisition, land loss, new/beginning (and transitioning) farmers, ranchers and forest landowners and sustainable agriculture were also timely as they informed policy recommendations such as federal comments, meetings with mayors across the Southern region, and our input to the USDA Equity Commission at a critical time. LLPP’s Executive Director contributed directly to that Commission’s recent final report as a member of the Agriculture Sub-Committee with critical contributions on: 1) providing non-loan options to prevent recurring heirs property dynamics in families; 2) increasing land access through funding of community-led land access and transition projects; 3) increasing funding for the Tenure, Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL); and 4) providing funding for cooperative agreements with community-based organizations and ensuring that heirship studies are inclusive with the fractionation issues of Tribal communities. The Rural Coalition submitted vital comments on these topics as well.

The project, “Securing Land Tenure Rights for Heirs Property Owners,” was designed to increase farmers’, ranchers’ and communities’ awareness of the barriers presented by heirs property and to provide access to trusted community resources through adoption of innovations by peer farmers, cooperatives, landowner associations, and project partners on using these new tools to address these barriers. The goals, objectives, and approaches were rooted in the Diffusion of Innovations theories popularized by Everett Rogers, which highlight the importance of finding early adopters to demonstrate and model new practices, and of utilizing peer networks to disseminate new ideas more broadly and accelerate adoption.

Two key long-term change strategies observed by Rogers include: 1) a highly respected individual within a social network adopting an innovation and creating a broader desire for that innovation within the network; and 2) introducing an innovation into a group of individuals, such as a farmer cooperative or a network of service providers, to support adoption of the innovation. In cooperator meetings, interviews, focus groups, and farmer/ landowner meetings, we heard clearly that clearing heirs property status is key to planning and implementing sustainable agriculture practices, because land ownership must first be sustainable. As a result, the project activities built on farmer/ landowner input in the Discover Phase and utilized these two strategies in the Build and Educate Phases to spread knowledge and practices; and then supported a broader change network through the Evaluation and Dissemination Phases, as described below.

Discover: The team built on focus groups and leveraged project activities for ongoing input to support farmers/ landowners in securing land tenure, ensuring economic wellbeing, and improving the environmental quality of their operations and social benefits to the communities.

The full project team, with leadership from the farm team formed of the cooperating farmers, provided workshops in each area using LLPP’s “10 Ways to Save Your Land.” Participants across these communities were then invited to participate in confidential focus groups followed by a survey. Focus groups utilized various techniques including dot allocation to identify key factors and prioritize influential concepts on the impact of these issues for families in the community to inform the survey. The surveys, which protect the identity of the participants, focused on the experience of the farm families and gathered key demographic data and farm enterprise data. Taken together these informed surveys centered around land tenure and farming practices helped unveil how land tenure arrangements and new tools are influencing farming operation choices, sustainability, and succession.

All our partners leveraged decades of experience and made extensive use of participatory research and popular education methodologies in the project. We aligned our research, data collection, reporting, and dissemination strategies, looked back on what we have achieved in the past, and leveraged the research, the input from interviews and focus groups, and the information gathered during workshops, technical assistance sessions and other connections with farmers and landowners to keep improving the work as well as the tools for information sharing about successes and solutions.

We employed and assessed the following methods in our work:

- Baseline Surveying and Assessment

- Group-Based Training and Information Sharing

- Individualized Technical Assistance

- Leadership Development and Increased Capacity of our Farmer Mentoring Network

- Project Team Field Visits/Conferences

- Outreach and Communications

- Data Collection, Results/Outcomes-Based Reporting and Participatory

Evaluation

- Resource Sharing and Information Dissemination

Land Tenure is Key to Agricultural Sustainability

An early pivot in the project structure came about as a result of input gleaned during the Discover phase. Having heard clearly during the Discover phase that heirs property status is only one of multiple, intersecting and interconnected issues typically faced by historically underserved producers and landowners, the Land Tenure Specialist team activities were redesigned to round out the range of support needed to understand, stabilize and advance land tenure.

The Land Tenure Specialist’s proposed scope of work included preparation of training modules and delivery of workshops on land ownership records, title searches, deeds, court records, and how to preserve documents. In reaching out to potential project partners, the SARE project team learned that The Conservation Fund’s Resourceful Communities Program had secured USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service funding to develop and deliver the same workshops. Since the Resourceful Communities workshop leads, Peg Kohring Cichon and McIntosh Sustainable Environment and Economic Development (McSEED), were able to reach the same target populations, the Land Tenure Specialist position was reconfigured to a team including Peg, McSEED, Mikki Sager (the original team member), Livia Marques and Savi Horne, all with extensive experience in working with farmers, landowners and communities. The scope of activities was broadened and deepened, to build on landowner input and lessons learned through the workshops, and to focus on the following impact areas, primarily in the Build and Educate categories:

- Technical Assistance: We provided technical assistance to producers, landowners, tribes and communities, including sharing information, providing one-on-one technical assistance to increase access to public dollars and providing direct connections to agencies, funding and other resources that have previously been functionally inaccessible.

- Policy: Farmer and landowner input helped to inform public policy suggestions and recommendations through participation in conferences, workshops, focus groups and individual interviews that enabled sharing of information gleaned through Discover phase, and learned from producers’ and partners’ lived and work experiences.

- Leveraging Resources: The public dollars available during the pandemic created opportunities for increasing access to funding, markets and other resources while also building skills and capacity for the long term, especially through network connections and new partnerships.

- Models: The resources available helped farmers and ranchers in developing models that are rooted in producers’ and landowners’ realities, are culturally informed and can influence future programming, policy development, and community and producer/ landowner efforts.

- Workshops: Hosting virtual and in-person workshops enabled producers and landowners to build skills; transfer knowledge about heirs property, estate planning, wills, trusts and LLCs; and build a base of trust for additional follow-up support to individuals and families.

Build: We built educational and policy materials and provided legal and technical assistance based on the recommendations and best practices to move producers to secured land tenure.

Based on input and insights gleaned during the Discover phase, the team developed additional questions and performed additional analysis using county level data from the Census of Agriculture, and on key concepts drawn from the broader literature. We employed this data to help each community develop insights on how to better structure outreach and technical assistance, and over time, to track results, by race, gender and ethnicity.

Workshops engaged farmers, ranchers, and landowners in target communities to develop specific recommendations on how heirs property related policy tools and educational materials are now working and how these can be improved to better meet the needs of farmers and communities. The focus was on how new farm bill policies related to heirs property, coupled with the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA) being adopted at the state level, can work to remove barriers to USDA program access, and help families address the difficult issues of family succession and benefit the community. The project activities were carried out with iterative and formative inputs informing adjustments to materials, updated alongside emerging business and ownership conditions and structures. Broadly, the project team carried out the following project activities, including:

- Outreach and Education: LLPP, RC, cooperator groups and Land Tenure Specialists hosted virtual and in-person workshops, shared materials developed in response to farmer/ landowner input, and made presentations at other entities’ gatherings, to build skills and transfer knowledge about sustainable agriculture, government programs, land tenure issues, heirs property, land acquisition/ rematriation, farm business opportunities and structures, legal structures, accessing public funding and more. We also developed professional development classes/ sessions to broaden the support and assistance network available to help historically underserved producers and landowners address sustainable agriculture production, conservation practices, heirs property and related land tenure and economic challenges; and build a trusted community of practice with skills and capacity to provide additional follow-up support to individuals and families.

- Legal Assistance: We heard, during the Discover phase, that farmers and landowners seldom have access to legal assistance they can trust, Project team partners provided access to, or direct legal and technical assistance to farmers, landowners, families, cooperatives, community-based organizations, and agriculturally-focused nonprofits, including sharing information; providing one-on-one legal assistance or technical support to address heirs property, foreclosure prevention, estate planning or other land tenure issues; helping families and groups of farmers/ landowners structure limited liability companies, agricultural and value-added food businesses, community farms and cooperatives/ collectives; and increasing access to public dollars and providing direct connections to agencies, funding and other resources that have previously been functionally inaccessible.

- Technical Assistance: Project team members provided a broad range of technical assistance to farmers, ranchers, landowners, tribal Nations, faith groups and community groups on sustainable agriculture, land tenure, land acquisition, government programs, and more. Topics and skills included but were not limited to: heirs property, risk management, climate smart agriculture, cover crops, wills, taxes, probates, partition sales, climate resiliency, debt relief, agricultural business plans, forming and operating cooperatives, USDA programs (DFAP, NAP, EQIP, Rural Development, etc.), the Farm Bill, and COVID-era funding opportunities.

- Leveraging Resources: We worked to help farmers, landowners, communities, tribes and other participants increase access to funding, markets and other resources as a means of building skills and capacity for the long term, especially through network and peer connections, new partnerships, and direct connections to agency professionals and public/ private funding sources.

- Supporting Models: We assisted farmers and landowners to develop operating models and legal/ business structures that are rooted in producers’ and landowners’ realities, are culturally informed and can influence farm operations, future programming, policy development, and community and producer/ landowner efforts.

Educate: We shared materials/ practices with farmers, extension agents, and communities, and grew the support network needed to adopt more ecologically and sustainable practices.

The educational materials and policy recommendations were shared with participating farmers, area extension agents, and policy makers for revisions and action. The partners tested materials during follow-up workshops, meetings and trainings using modules that were tested and evaluated by the Farm Team and during the trainings, and were revised, updated and shared with others for final review, including at the annual Winter Forum of the Rural Coalition, and at the trainings held annually by Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project and Operation Spring Plant.

- Workshops: We hosted virtual and in-person workshops to build skills, transfer knowledge, and build a base of trust for additional follow-up support to individuals, families, communities, faith groups, tribal governments and Native entities.

SUMMARY TALLY OF CRITICAL PROJECT ACTIVITIES AND OUTPUTS

Over the course of the extended three-year project period, the project team engaged in the following activities and produced the results tallied below:

Outreach and Education: 8,924 individuals participated in 184 virtual and in-person workshops, including historically underserved, socially disadvantaged farmers/ ranchers/ homeowner farmers/ small-acreage farmers/ landowners/ women and veteran producers, as well as community leaders and members; land, racial justice and elder abuse prevention advocates; senior and disabled homeowners, caregivers and service providers; homeowners with forestland; FSA and agricultural and rural leaders; legal practitioners and advocates for farmers and homeowners; local and statewide service providers in healthcare, emergency services, home restoration, agricultural services, education, law; conservation finance, agency and philanthropic leaders; students and academics in agriculture, law and conservation; small business owners; local and regional government leaders.

Over 12,000 packets of educational materials were distributed, with thousands more individual educational documents being distributed during the three-year project period. In addition to updating “Ten Ways to Save Your Land,” the LLPP team created and distributed 105 copies of a special activity book on estate planning for children, in response to input about the need to educate and meaningfully engage future generations around land tenure. Topics addressed included: heirs property, estate planning, wills preparation, foreclosure prevention, disaster preparedness/ relief/ recovery, farm business entity formation, cooperatives, and more. Virtual and in-person workshop participants included 34 producers, 452 individual landowners, and over 150 community leaders from throughout North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. An additional 6 historically underserved community groups developed plans and accessed funding through support in developing community-led food system models.

Legal Assistance: A broad range of legal and technical assistance was provided, with 1,246 legal matters addressed in 77 of North Carolina’s 100 counties, including the most socially and economically distressed counties. These included: 210 lending and finance-related matters, including debt restructuring, consumer issues, and foreclosure defense, including bankruptcy; 367 real property matters such as adverse possession, boundary disputes and heirs property; 77 agricultural business issues including rural economic development, incorporation, tax-exempt status support, land use, environmental issues and miscellaneous matters such as tenancy; 71 civil and individual rights matters, including issues involving the USDA; and support to 521 individuals/families on preparing wills and estate planning. The legal and technical assistance in North Carolina preserved land, homes and farms with a tax value of $6,629,430, retaining generational wealth and critical assets for families in need and protecting farms and agricultural businesses.

Technical Assistance: A broad range of technical assistance was provided to over 630 farmers and ranchers who all qualify as socially disadvantaged, beginning/ young, historically underserved, women, and/ or veteran. Skills built and topics covered included, but were now limited to: securing farm numbers, financial recordkeeping, applying for reduced taxation programs, coaching and assistance in preparing EQIP applications, beekeeping and pollinator pathways, climate smart agriculture, cover crops, registering to supply vegetables under the USDA Local Food for School Cooperative Agreement Program, learning about preferences that veterans are eligible for, accessing new markets such as selling cotton to Cargill via the Black Equity Program, securing high tunnels and rainwater harvesting equipment funding, protecting inherited land via a land trust, and more. Additional assistance was provided to 96 individual landowners and 8 landowner families comprising more than 85 individuals; one federally recognized tribal nation; and at least four excluded communities/ historically underserved community- based organizations (CBOs).

Leveraging Resources: In addition to the project lead organizations raising $10 million in federal funding for outreach services, and sustainable agriculture business support, we also helped partner farmers and communities raise over $4.7 million to advance sustainable agriculture, strengthen farm and cooperative operations, access new markets, secure farm equipment and more. This included supporting the efforts of 6 tribes, 8 rural food hubs and three community-based organizations secure over $3.75 million in funding to support general operations, land acquisition, food businesses, local food systems and more; plus assisting 4 Texas landowners in obtaining $224,000 in grants to purchase new farming equipment via the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality; and we supported 3 farmers and one market cooperative in securing over $700,000 to strengthen operations and increase access to new markets.

Supporting Models: Project team members provided support to cooperatives and collectives supporting more than 260 historically underserved and socially disadvantaged farmers/ landowners/ value-added food processors in strengthening their operations, increasing revenues, increasing access to public and private funding, increasing access to public conservation programs and implementing sustainable agriculture practices. We were instrumental in assisting BIPOC collaboratives and networks in securing over $700,000 that was distributed to historically underserved, socially disadvantaged, young, beginning, women and veteran farmers and landowners to strengthen agriculturally-based businesses, and to establish an East Coast agroecology center serving the Southern Black Belt. Likewise, our collaborative advocacy framework resulted in the NC Department of Agriculture securing millions of federal dollars to increase food access in communities and schools throughout the state, while working with underserved farmers to help them access produce markets locally and across the state. An additional 94 individual producers strengthened their operations through increased access to markets, support to producer cooperatives, and access to shared equipment.

Informing Policy: The project team members shared information gleaned from the Discover Phase and throughout the project period to both inform and support public policy regarding land tenure, agricultural production, access to capital and markets, and more. In several cases, LLPP provided direct support to heirs property owners who were being denied COVID relief housing assistance funds because individual names were not on the real property deeds. LLPP documented the legal basis for the funding to be awarded. At the same time, LLPP engaged in shaping with policy collaborators the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) and bringing to fruition the land access program which provided transformational capital to three community-based nonprofits to assist BIPOC farmers; served on the Agriculture Committee of the USDA Equity Commission; and, in the 2023-23 grant period, contributed to the interim report that recommended enhanced diversity across USDA, furthered opportunities for people of color, and addressing of discrimination. Project team members also provided thought partnership, input and policy recommendations to Federal Reserve Board, USDA-Forest Service, Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, and national intermediaries (The Wilderness Society, Environmental Defense Fund, Aspen Institute), regarding land/ food/ economic/ environmental/ climate challenges. Additional policy recommendations provided by RC are noted below:

- (2022 - Letter to Chairman Bishop and Ranking Member Fortenberry:)

- (i) Relending Program To Resolve Ownership And Succession On Farmland. Under Section 5104 of the 2018 Farm Bill, the Congress authorized a new USDA Farm Service Agency intermediary relending pilot program to resolve heirs’ property issues that cloud title to agricultural lands and prevent participation in critical USDA programs. The Revolving Loan pilot authorized under Section 5104 permits USDA loans to heirs property interest holders for the purpose of purchasing the interests of non-farming heirs who desire to sell their interest to family members intending to actively farm the land.

- Section 5104 authorizes an appropriation up to $10 million annually. We request the committee provide the full $10 million for FY 2020 in order to allow the Secretary to initiate and establish 3(three) or more pilot relending programs to best assess different methods and models for relending, and best inform a report with recommendations for improvement and continuation.

- (ii) Farmland Ownership Data Collection. Section 12607 of the 2018 Farm Bill created the Farmland Ownership Data Collection initiative with the specific charge of capturing data trends in farmland (a) ownership, (b) tenure, (c) generational transitions, (d) and barriers to entry for beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers. The data and studies compiled under Section 12607 can be used to inform and guide all levels of agricultural policymaking that concern the critical dynamics of heirs’ property and absentee land ownership in farming communities. Further, we recommend an appropriation of $3 million in FY 2020 in order to implement the collection of data that supports the need for a robust and viable plan for the efficient transition of farmland to the next generation of farmers and ranchers.

Evaluate: Research findings and metrics were documented and informed development of new materials, business models and operating structures to strengthen production and land tenure.

Research findings and metrics are reported above and below, including numbers of farmers and communities reached, number of wills completed, and the outcomes of heirs property representation provided, including use of the UPHPA.

The team also shared for review with extension personnel and policy makers a report analyzing the view of farmers and communities of the efficacy of new policy tools coupled with training modules to return dormant land to farming and pass it on to new generations, and otherwise affect the ecological status, economic well-being and quality of life of the farmer, her/his family, and the community. The efficacy of the materials produced will be evaluated using a pretest/post-test design and amended for final dissemination.

The team will further assess the extent to which new farm bill policies related to heirs property, coupled with the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act being adopted at the state level, are functioning to remove barriers to USDA program access, and enabling families to address the complex issues of family succession in the farming vocation.

Disseminate: Educational materials and policy proposals were made available to producers, extension agents, advocates, support groups, key policy makers.

Educational material and policy proposals have been made available for producers, partner organizations and related CBO networks, and extension agents nationwide, on websites, in annual meetings held by each group and distributed to and discussed with key policy makers.

See Additional Attachments:

Not applicable. Project Objectives remained as orginally proposed:

- Discover: The team will develop an in-depth understanding of the experience of farming communities and families in addressing farm succession issues, and how new farm bill policies related to heirs property and related state laws, are working to remove barriers to USDA program access and return dormant land to production.

- Build: Using findings, the team will engage communities to develop recommendations on improving heirs property policies and educational materials to better meet the needs of farmers and communities

- Educate: Materials and Recommendations will be refined with participating farmers and area extension agents.

- Evaluate: Materials refined are evaluated for final dissemination.

- Disseminate: Educational material and policy proposals will be made available to producers and extension agents nationwide and key policy makers.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Copied & Pasted from Abstract Section:

The principal investigator partners, North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers Land Loss Prevention Project (LLPP) and Rural Coalition (RC) coordinated the overall research and education planning, and administration of this SSARE project across the LLPP collaboration base and the RC’s membership, including cooperator groups (Operation Spring Plant, Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project, Inc., Rural Advancement Fund of the National Sharecroppers Fund, and Texas Coalition of Rural Landowners). During FY2021-2023, this entailed meeting with cooperators to pivot research and implementation approaches during the Pandemic and to consider emerging environmental, disaster, and federal program-related needs and opportunities (i.e., White House, Congressional and USDA programs ranging across HRSA, ARPA, IRA, DFAP, ERP and others).

Our findings related to heirs property, land acquisition, land loss, new/beginning (and transitioning) farmers, ranchers and forest landowners and sustainable agriculture were also timely as they informed policy recommendations such as federal comments, meetings with mayors across the Southern region, and our input to the USDA Equity Commission at a critical time. LLPP’s Executive Director contributed directly to that Commission’s recent final report as a member of the Agriculture Sub-Committee with critical contributions on: 1) providing non-loan options to prevent recurring heirs property dynamics in families; 2) increasing land access through funding of community-led land access and transition projects; 3) increasing funding for the Tenure, Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL); and 4) providing funding for cooperative agreements with community-based organizations and ensuring that heirship studies are inclusive with the fractionation issues of Tribal communities. The Rural Coalition submitted vital comments on these topics as well.

The project, “Securing Land Tenure Rights for Heirs Property Owners,” was designed to increase farmers’, ranchers’ and communities’ awareness of the barriers presented by heirs property and to provide access to trusted community resources through adoption of innovations by peer farmers, cooperatives, landowner associations, and project partners on using these new tools to address these barriers. The goals, objectives, and approaches were rooted in the Diffusion of Innovations theories popularized by Everett Rogers, which highlight the importance of finding early adopters to demonstrate and model new practices, and of utilizing peer networks to disseminate new ideas more broadly and accelerate adoption.

Two key long-term change strategies observed by Rogers include: 1) a highly respected individual within a social network adopting an innovation and creating a broader desire for that innovation within the network; and 2) introducing an innovation into a group of individuals, such as a farmer cooperative or a network of service providers, to support adoption of the innovation. In cooperator meetings, interviews, focus groups, and farmer/ landowner meetings, we heard clearly that clearing heirs property status is key to planning and implementing sustainable agriculture practices, because land ownership must first be sustainable. As a result, the project activities built on farmer/ landowner input in the Discover Phase and utilized these two strategies in the Build and Educate Phases to spread knowledge and practices; and then supported a broader change network through the Evaluation and Dissemination Phases, as described below.

Discover: The team built on focus groups and leveraged project activities for ongoing input to support farmers/ landowners in securing land tenure, ensuring economic wellbeing, and improving the environmental quality of their operations and social benefits to the communities.

The full project team, with leadership from the farm team formed of the cooperating farmers, provided workshops in each area using LLPP’s “10 Ways to Save Your Land.” Participants across these communities were then invited to participate in confidential focus groups followed by a survey. Focus groups utilized various techniques including dot allocation to identify key factors and prioritize influential concepts on the impact of these issues for families in the community to inform the survey. The surveys, which protect the identity of the participants, focused on the experience of the farm families and gathered key demographic data and farm enterprise data. Taken together these informed surveys centered around land tenure and farming practices helped unveil how land tenure arrangements and new tools are influencing farming operation choices, sustainability, and succession.

All our partners leveraged decades of experience and made extensive use of participatory research and popular education methodologies in the project. We aligned our research, data collection, reporting, and dissemination strategies, looked back on what we have achieved in the past, and leveraged the research, the input from interviews and focus groups, and the information gathered during workshops, technical assistance sessions and other connections with farmers and landowners to keep improving the work as well as the tools for information sharing about successes and solutions.

We employed and assessed the following methods in our work:

- Baseline Surveying and Assessment

- Group-Based Training and Information Sharing

- Individualized Technical Assistance

- Leadership Development and Increased Capacity of our Farmer Mentoring Network

- Project Team Field Visits/Conferences

- Outreach and Communications

- Data Collection, Results/Outcomes-Based Reporting and Participatory

Evaluation

- Resource Sharing and Information Dissemination

Land Tenure is Key to Agricultural Sustainability

An early pivot in the project structure came about as a result of input gleaned during the Discover phase. Having heard clearly during the Discover phase that heirs property status is only one of multiple, intersecting and interconnected issues typically faced by historically underserved producers and landowners, the Land Tenure Specialist team activities were redesigned to round out the range of support needed to understand, stabilize and advance land tenure.

The Land Tenure Specialist’s proposed scope of work included preparation of training modules and delivery of workshops on land ownership records, title searches, deeds, court records, and how to preserve documents. In reaching out to potential project partners, the SARE project team learned that The Conservation Fund’s Resourceful Communities Program had secured USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service funding to develop and deliver the same workshops. Since the Resourceful Communities workshop leads, Peg Kohring Cichon and McIntosh Sustainable Environment and Economic Development (McSEED), were able to reach the same target populations, the Land Tenure Specialist position was reconfigured to a team including Peg, McSEED, Mikki Sager (the original team member), Livia Marques and Savi Horne, all with extensive experience in working with farmers, landowners and communities. The scope of activities was broadened and deepened, to build on landowner input and lessons learned through the workshops, and to focus on the following impact areas, primarily in the Build and Educate categories:

- Technical Assistance: We provided technical assistance to producers, landowners, tribes and communities, including sharing information, providing one-on-one technical assistance to increase access to public dollars and providing direct connections to agencies, funding and other resources that have previously been functionally inaccessible.

- Policy: Farmer and landowner input helped to inform public policy suggestions and recommendations through participation in conferences, workshops, focus groups and individual interviews that enabled sharing of information gleaned through Discover phase, and learned from producers’ and partners’ lived and work experiences.

- Leveraging Resources: The public dollars available during the pandemic created opportunities for increasing access to funding, markets and other resources while also building skills and capacity for the long term, especially through network connections and new partnerships.

- Models: The resources available helped farmers and ranchers in developing models that are rooted in producers’ and landowners’ realities, are culturally informed and can influence future programming, policy development, and community and producer/ landowner efforts.

- Workshops: Hosting virtual and in-person workshops enabled producers and landowners to build skills; transfer knowledge about heirs property, estate planning, wills, trusts and LLCs; and build a base of trust for additional follow-up support to individuals and families.

Build: We built educational and policy materials and provided legal and technical assistance based on the recommendations and best practices to move producers to secured land tenure.

Based on input and insights gleaned during the Discover phase, the team developed additional questions and performed additional analysis using county level data from the Census of Agriculture, and on key concepts drawn from the broader literature. We employed this data to help each community develop insights on how to better structure outreach and technical assistance, and over time, to track results, by race, gender and ethnicity.

Workshops engaged farmers, ranchers, and landowners in target communities to develop specific recommendations on how heirs property related policy tools and educational materials are now working and how these can be improved to better meet the needs of farmers and communities. The focus was on how new farm bill policies related to heirs property, coupled with the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA) being adopted at the state level, can work to remove barriers to USDA program access, and help families address the difficult issues of family succession and benefit the community. The project activities were carried out with iterative and formative inputs informing adjustments to materials, updated alongside emerging business and ownership conditions and structures. Broadly, the project team carried out the following project activities, including:

- Outreach and Education: LLPP, RC, cooperator groups and Land Tenure Specialists hosted virtual and in-person workshops, shared materials developed in response to farmer/ landowner input, and made presentations at other entities’ gatherings, to build skills and transfer knowledge about sustainable agriculture, government programs, land tenure issues, heirs property, land acquisition/ rematriation, farm business opportunities and structures, legal structures, accessing public funding and more. We also developed professional development classes/ sessions to broaden the support and assistance network available to help historically underserved producers and landowners address sustainable agriculture production, conservation practices, heirs property and related land tenure and economic challenges; and build a trusted community of practice with skills and capacity to provide additional follow-up support to individuals and families.

- Legal Assistance: We heard, during the Discover phase, that farmers and landowners seldom have access to legal assistance they can trust, Project team partners provided access to, or direct legal and technical assistance to farmers, landowners, families, cooperatives, community-based organizations, and agriculturally-focused nonprofits, including sharing information; providing one-on-one legal assistance or technical support to address heirs property, foreclosure prevention, estate planning or other land tenure issues; helping families and groups of farmers/ landowners structure limited liability companies, agricultural and value-added food businesses, community farms and cooperatives/ collectives; and increasing access to public dollars and providing direct connections to agencies, funding and other resources that have previously been functionally inaccessible.

- Technical Assistance: Project team members provided a broad range of technical assistance to farmers, ranchers, landowners, tribal Nations, faith groups and community groups on sustainable agriculture, land tenure, land acquisition, government programs, and more. Topics and skills included but were not limited to: heirs property, risk management, climate smart agriculture, cover crops, wills, taxes, probates, partition sales, climate resiliency, debt relief, agricultural business plans, forming and operating cooperatives, USDA programs (DFAP, NAP, EQIP, Rural Development, etc.), the Farm Bill, and COVID-era funding opportunities.

- Leveraging Resources: We worked to help farmers, landowners, communities, tribes and other participants increase access to funding, markets and other resources as a means of building skills and capacity for the long term, especially through network and peer connections, new partnerships, and direct connections to agency professionals and public/ private funding sources.

- Supporting Models: We assisted farmers and landowners to develop operating models and legal/ business structures that are rooted in producers’ and landowners’ realities, are culturally informed and can influence farm operations, future programming, policy development, and community and producer/ landowner efforts.

Educate: We shared materials/ practices with farmers, extension agents, and communities, and grew the support network needed to adopt more ecologically and sustainable practices.

The educational materials and policy recommendations were shared with participating farmers, area extension agents, and policy makers for revisions and action. The partners tested materials during follow-up workshops, meetings and trainings using modules that were tested and evaluated by the Farm Team and during the trainings, and were revised, updated and shared with others for final review, including at the annual Winter Forum of the Rural Coalition, and at the trainings held annually by Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project and Operation Spring Plant.

- Workshops: We hosted virtual and in-person workshops to build skills, transfer knowledge, and build a base of trust for additional follow-up support to individuals, families, communities, faith groups, tribal governments and Native entities.

SUMMARY TALLY OF CRITICAL PROJECT ACTIVITIES AND OUTPUTS

Over the course of the extended three-year project period, the project team engaged in the following activities and produced the results tallied below:

Outreach and Education: 8,924 individuals participated in 184 virtual and in-person workshops, including historically underserved, socially disadvantaged farmers/ ranchers/ homeowner farmers/ small-acreage farmers/ landowners/ women and veteran producers, as well as community leaders and members; land, racial justice and elder abuse prevention advocates; senior and disabled homeowners, caregivers and service providers; homeowners with forestland; FSA and agricultural and rural leaders; legal practitioners and advocates for farmers and homeowners; local and statewide service providers in healthcare, emergency services, home restoration, agricultural services, education, law; conservation finance, agency and philanthropic leaders; students and academics in agriculture, law and conservation; small business owners; local and regional government leaders.

Over 12,000 packets of educational materials were distributed, with thousands more individual educational documents being distributed during the three-year project period. In addition to updating “Ten Ways to Save Your Land,” the LLPP team created and distributed 105 copies of a special activity book on estate planning for children, in response to input about the need to educate and meaningfully engage future generations around land tenure. Topics addressed included: heirs property, estate planning, wills preparation, foreclosure prevention, disaster preparedness/ relief/ recovery, farm business entity formation, cooperatives, and more. Virtual and in-person workshop participants included 34 producers, 452 individual landowners, and over 150 community leaders from throughout North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. An additional 6 historically underserved community groups developed plans and accessed funding through support in developing community-led food system models.

Legal Assistance: A broad range of legal and technical assistance was provided, with 1,246 legal matters addressed in 77 of North Carolina’s 100 counties, including the most socially and economically distressed counties. These included: 210 lending and finance-related matters, including debt restructuring, consumer issues, and foreclosure defense, including bankruptcy; 367 real property matters such as adverse possession, boundary disputes and heirs property; 77 agricultural business issues including rural economic development, incorporation, tax-exempt status support, land use, environmental issues and miscellaneous matters such as tenancy; 71 civil and individual rights matters, including issues involving the USDA; and support to 521 individuals/families on preparing wills and estate planning. The legal and technical assistance in North Carolina preserved land, homes and farms with a tax value of $6,629,430, retaining generational wealth and critical assets for families in need and protecting farms and agricultural businesses.

Technical Assistance: A broad range of technical assistance was provided to over 630 farmers and ranchers who all qualify as socially disadvantaged, beginning/ young, historically underserved, women, and/ or veteran. Skills built and topics covered included, but were now limited to: securing farm numbers, financial recordkeeping, applying for reduced taxation programs, coaching and assistance in preparing EQIP applications, beekeeping and pollinator pathways, climate smart agriculture, cover crops, registering to supply vegetables under the USDA Local Food for School Cooperative Agreement Program, learning about preferences that veterans are eligible for, accessing new markets such as selling cotton to Cargill via the Black Equity Program, securing high tunnels and rainwater harvesting equipment funding, protecting inherited land via a land trust, and more. Additional assistance was provided to 96 individual landowners and 8 landowner families comprising more than 85 individuals; one federally recognized tribal nation; and at least four excluded communities/ historically underserved community- based organizations (CBOs).

Leveraging Resources: In addition to the project lead organizations raising $10 million in federal funding for outreach services, and sustainable agriculture business support, we also helped partner farmers and communities raise over $4.7 million to advance sustainable agriculture, strengthen farm and cooperative operations, access new markets, secure farm equipment and more. This included supporting the efforts of 6 tribes, 8 rural food hubs and three community-based organizations secure over $3.75 million in funding to support general operations, land acquisition, food businesses, local food systems and more; plus assisting 4 Texas landowners in obtaining $224,000 in grants to purchase new farming equipment via the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality; and we supported 3 farmers and one market cooperative in securing over $700,000 to strengthen operations and increase access to new markets.

Supporting Models: Project team members provided support to cooperatives and collectives supporting more than 260 historically underserved and socially disadvantaged farmers/ landowners/ value-added food processors in strengthening their operations, increasing revenues, increasing access to public and private funding, increasing access to public conservation programs and implementing sustainable agriculture practices. We were instrumental in assisting BIPOC collaboratives and networks in securing over $700,000 that was distributed to historically underserved, socially disadvantaged, young, beginning, women and veteran farmers and landowners to strengthen agriculturally-based businesses, and to establish an East Coast agroecology center serving the Southern Black Belt. Likewise, our collaborative advocacy framework resulted in the NC Department of Agriculture securing millions of federal dollars to increase food access in communities and schools throughout the state, while working with underserved farmers to help them access produce markets locally and across the state. An additional 94 individual producers strengthened their operations through increased access to markets, support to producer cooperatives, and access to shared equipment.

Informing Policy: The project team members shared information gleaned from the Discover Phase and throughout the project period to both inform and support public policy regarding land tenure, agricultural production, access to capital and markets, and more. In several cases, LLPP provided direct support to heirs property owners who were being denied COVID relief housing assistance funds because individual names were not on the real property deeds. LLPP documented the legal basis for the funding to be awarded. At the same time, LLPP engaged in shaping with policy collaborators the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) and bringing to fruition the land access program which provided transformational capital to three community-based nonprofits to assist BIPOC farmers; served on the Agriculture Committee of the USDA Equity Commission; and, in the 2023-23 grant period, contributed to the interim report that recommended enhanced diversity across USDA, furthered opportunities for people of color, and addressing of discrimination. Project team members also provided thought partnership, input and policy recommendations to Federal Reserve Board, USDA-Forest Service, Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, and national intermediaries (The Wilderness Society, Environmental Defense Fund, Aspen Institute), regarding land/ food/ economic/ environmental/ climate challenges. Additional policy recommendations provided by RC are noted below:

- (2022 - Letter to Chairman Bishop and Ranking Member Fortenberry:)

- (i) Relending Program To Resolve Ownership And Succession On Farmland. Under Section 5104 of the 2018 Farm Bill, the Congress authorized a new USDA Farm Service Agency intermediary relending pilot program to resolve heirs’ property issues that cloud title to agricultural lands and prevent participation in critical USDA programs. The Revolving Loan pilot authorized under Section 5104 permits USDA loans to heirs property interest holders for the purpose of purchasing the interests of non-farming heirs who desire to sell their interest to family members intending to actively farm the land.

- Section 5104 authorizes an appropriation up to $10 million annually. We request the committee provide the full $10 million for FY 2020 in order to allow the Secretary to initiate and establish 3(three) or more pilot relending programs to best assess different methods and models for relending, and best inform a report with recommendations for improvement and continuation.

- (ii) Farmland Ownership Data Collection. Section 12607 of the 2018 Farm Bill created the Farmland Ownership Data Collection initiative with the specific charge of capturing data trends in farmland (a) ownership, (b) tenure, (c) generational transitions, (d) and barriers to entry for beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers. The data and studies compiled under Section 12607 can be used to inform and guide all levels of agricultural policymaking that concern the critical dynamics of heirs’ property and absentee land ownership in farming communities. Further, we recommend an appropriation of $3 million in FY 2020 in order to implement the collection of data that supports the need for a robust and viable plan for the efficient transition of farmland to the next generation of farmers and ranchers.

Evaluate: Research findings and metrics were documented and informed development of new materials, business models and operating structures to strengthen production and land tenure.

Research findings and metrics are reported above and below, including numbers of farmers and communities reached, number of wills completed, and the outcomes of heirs property representation provided, including use of the UPHPA.

The team also shared for review with extension personnel and policy makers a report analyzing the view of farmers and communities of the efficacy of new policy tools coupled with training modules to return dormant land to farming and pass it on to new generations, and otherwise affect the ecological status, economic well-being and quality of life of the farmer, her/his family, and the community. The efficacy of the materials produced will be evaluated using a pretest/post-test design and amended for final dissemination.

The team will further assess the extent to which new farm bill policies related to heirs property, coupled with the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act being adopted at the state level, are functioning to remove barriers to USDA program access, and enabling families to address the complex issues of family succession in the farming vocation.

Disseminate: Educational materials and policy proposals were made available to producers, extension agents, advocates, support groups, key policy makers.

Educational material and policy proposals have been made available for producers, partner organizations and related CBO networks, and extension agents nationwide, on websites, in annual meetings held by each group and distributed to and discussed with key policy makers.

See prevoiusly referenced Attachement: Attachment 1 - 2021 - 2024 - SARE LS21-356 Final Report Tally

Research and Information Products

- Heirs Property Guide for Communities (updated 2022, 2023)

- 10 Ways to Save Your Land (Updated with LLPP 2022)

- RC Community Profiles with County Level Data

- AFRI Report to Partners (2022)

- Workshops on How to Buy Land

- Tribal Partner Workshops

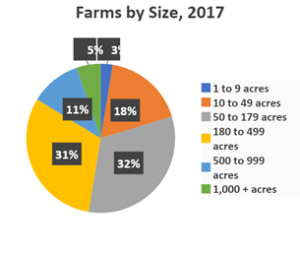

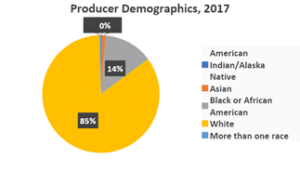

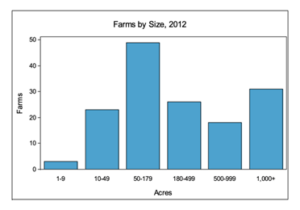

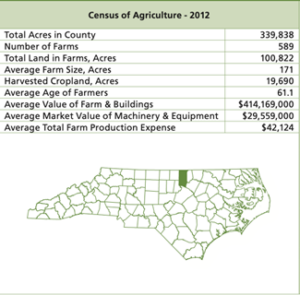

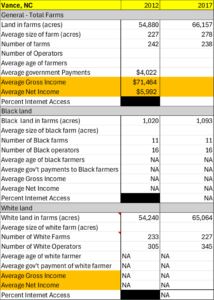

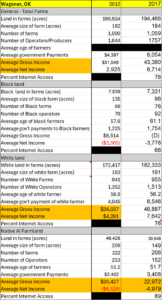

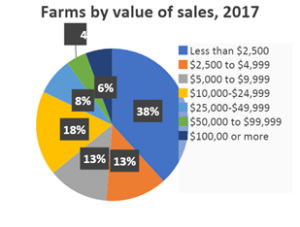

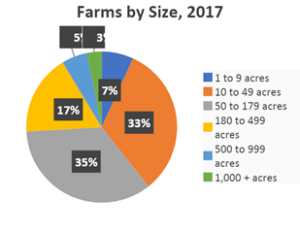

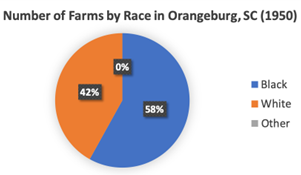

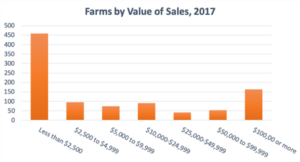

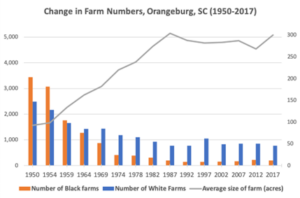

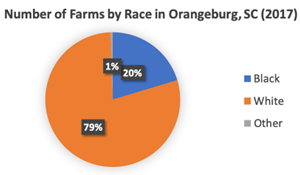

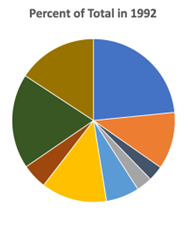

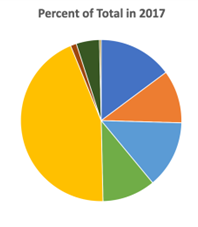

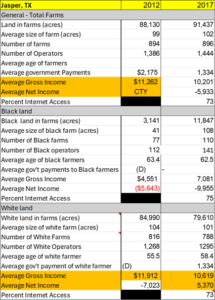

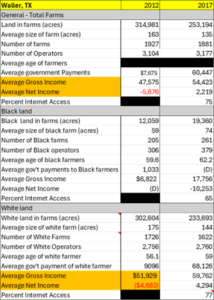

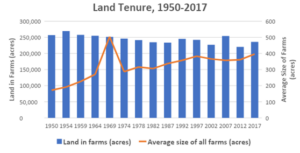

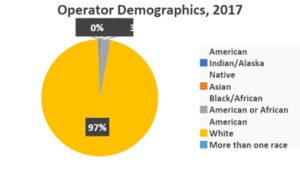

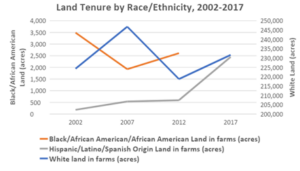

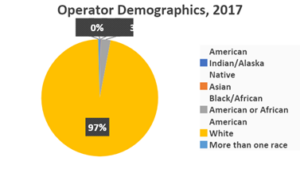

With respect to farmer-led data analysis in 2022, RC provided NASS County and Race/Ethnicity/ Gender County profiles (2012 and 2017) to cooperators during the planning and “discover” stages of this project. As our work advanced, RC created a template for community (county-level) profiles with special attention to variations in changes in the overall, average, and median acreages of land held in each county by race and ethnicity. We used Orangeburg, SC as our first example, because we had compiled data back to the 1959 Census of Agriculture that allowed us to better understand changes in the total amount of land in agriculture in the county over time. RC also included data on other production and economic differences and how these changed across all data-collection periods compared with national trends. The RC Research Team completed similar profiles and reviewed county and area-specific profiles with each cooperator. (RC also aggregated and included county-level data from the Social Vulnerability Index from the Centers for Disease Control and USDA data on poverty, Internet access, and several related questions.)

In October 2022, RC generated a report to CBO partners working in either the AFRI or SARE projects. The report employed existing NASS data and interpreted quantitative and qualitative results of the AFRI survey, which was piloted alongside outreach and TA events (focused on land tenure, heirs property, encumbrances, recordkeeping, wills, leases) in Alabama with Cottage House and Oklahoma with OBHRPI. (Qualtrics was used to document and analyze survey pilot data.) This report was reviewed with 18 partners, enabling us to understand trends, especially in areas where data is unavailable (because of privacy of information concerns, lack of participation in USDA, lack of trust) and to hone our farmer-led research methodologies.

This final report discusses how community-specific methodologies were identified, disseminated, and evolved across the research period. It also includes data from partner and participant interviews.

FY2022 Research Timeline

- Rural Coalition staff revised a briefer version of the survey in collaboration with the Farm Advisory Team as a “screening tool,” which was administered twice during the month of August by Rural Coalition and organizational partner, Cottage House, Inc. in the state of Alabama.

- Thirty-nine (39) participants completed the survey during a meeting hosted by Cottage House, or at the follow-up weekend workshop hosted with the Ma-Chis Lower Creek Indian Tribe of Alabama during the first week of August. An attorney was present to answer questions about heirs property and legal encumbrances.

- RC staff entered data from these two surveys into Qualtrics, performed a rough analysis of the data utilizing capacities and expertise with the newly expanded Recordkeeping Team, and conducted an interview with CHI director about the results.

- RC updated the Qualtrics data management software to include SPSS, standard regression, and other statistical analysis tools.

- In October, RC produced a 24-page report [submitted with this report as an additional document] for research partners to examine and discuss key learnings, changes, and challenges and to enable collaborators to determine together the most productive way to advance the next research stage, including administering a shorter version of the survey and revising our focus group methodology if needed. The report also raises for discussion the significance of certain questions and how this can be better conveyed to participants. For example, the report raises why gender should not be omitted and why race/ethnicity data are incredibly valuable to USDA, Congress, and policymakers.

- Report summary: The purpose of the report to the research partners was and continues to inform a thoughtful review with AFRI research partners and farm advisory team members. NASS and related census data, especially County, State and REG (Race, Ethnicity, Gender) Profiles to shed light on the current results including Characteristics of the Farmer; the Characteristics of the Farm; Participation in USDA Programs; Record Keeping, Risk Management, Natural Resource Rights; and Family, Heirs Property and Community Change. Subsections focused on farmer data primarily from farmer respondents and data from all participating landowners, both farmers and non-farmers. Each sub-section concluded with a discussion of research considerations, such as the quality of the data collected with this instrument and suggestions for overcoming challenges to its interpretation. A series of tables presented data collected in the 2004-2005 Record Keeping Survey with 1000 Minority Farmers to compare with the current effort. The report also presents a slightly revised focus group protocol and an appendix with an evaluation table from the prior study and current evaluation questions.

- In the review of results with Cottage House (by phone interview on 8/22/22), we also captured emerging methodologies such as the “Do you know your land? The Walking Interview Assessment” employed by Mrs. Barbara Shipman. This walk is an informal, physical survey of the farm with the owner/s, which often culminates in a review of existing documents and a discussion of what is in them. Mrs. Shipman finds that many farmers with whom CHI works discover “old-time deeds” with buried clauses that prevent the sale of land and/or mineral and other rights, and that increase vulnerability to fracking and other predatory schemes. CHI is eager for the next stage of research to identify these and other encumbrances at a more granular level as described in objective three.

- The Report to Partners was shared with LLPP in preparation for the meeting reported under objective 2 and is currently being updated to include data insights from the survey conducted in Oklahoma in November and a follow up review with OBHRPI.

- A version of the survey containing many of the 2007 questions as well as new questions was piloted by the Oklahoma Black Historical Research Project, Inc. in July 2022 and determined to be too long for participants to complete fully in a reasonable amount of time. The survey was honed to 69 questions and readministered with a smaller group of 12 participants (all with farmland ownership, 9 farmers) in November 2022. These respondents participated in a meeting and nearly all survey questions were answered.

- Rural Coalition’s 14th Annual Winter Policy and Research Forum that was initially scheduled for December 2022, was conducted from January 19 to 20th. This meeting gathered more than 200 participants, including RC members, farmers, USDA staff and officials, and touched on many of the project’s research themes. 9 of the 11 CBO Research partners who were present determined that a review of the Forum would assist in framing the final phase of the AFRI and SSARE research projects to achieve overlapping objectives.

Insights from Interviews and 2022 Census Review: In 2024, Texas continues to have the most black farmers; Oklahoma SDFR farms have largely cow-calf operations, because of the lower quality of land, drought has been the primary challenge over the 2022-2024 period; South Carolina has historically and currently has a preponderance of row crop farmers, where interviews and outreach confirm that elder farmers want to "keep land from becoming heirs property." When asked what motivates SDFRs to resolve heirs property, farm community leaders said that it is the ability to make their operations more sustainable and participate in farm programs.

When asked to define or describe sustainability, one farm leader and SARE cooperator/partner said that the ability to hold on to the land (pay bills and taxes), take care of the land (conservation), and pass the land to future generations (family and new and beginning farmers) are the three most important things to a Socially-disadvantaged farmer, rancher or landowner, forest landowner who is often an elder.

Profitability is defined as “making enough” to do these things. Not making enough accelerates land loss and the loss of farmers in these communities. “No one [young] can make enough.”

And the “Land Grant Institutions (1890s and otherwise) are phasing out education for what I call ‘dirt farmers’, instead they are focusing on Agribusiness and other careers, so nobody wants to or knows how to farm.”

During 2022 and throughout 2023, it was called to our attention that producers were being approached by notaries and other such entities. These entities told (and continue to tell) farmers, ranchers, and landowners that they can help them receive USDA farm program benefits. Farmers and landowners are asked to complete a Power of Attorney (PoA) form granting the entity authority to conduct USDA business on their behalf. The grantees who receive this authority then apply for certain benefits on behalf of the farmer. The entities have an additional agreement with the farmer, often unwritten, to take a cut, ranging from 10-30%, of any benefits the farmer receives. The producers are not informed there is no cost for USDA services. After joining the meeting with Mayors across the Southeast to explain the issues of heirs property, the need for the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act at the state level and its implementation where it has been passed (e.g. Texas) became evident.

Supporting Cottage House’s heirs property training, focus groups and survey administration in 2022 and learning about their approach to TA, RC created a Partners Community Report on County Level Data (Pilot Survey Results), reviewed the report and pilot survey in a meeting with 18 partners (CBO staff and farm leaders, researchers, co-PIs), revised the pilot survey and contributed to the 2023 updated Community Guide with LLPP. The RC review of data with cooperators assists the collaborative effort between cooperators, farmer and rural communities, and USDA by examining the trends across counties, states, regions and the nation as well as programmatic needs and emergent concerns.

When the 2022 Ag Census was released on Feb 15, 2024, RC worked with NASS to acquire data for the counties of work in this project. The RC filtered this data to share with cooperators during the reporting interviews and intake sessions for this report.

SSARE NARRATIVES BY COUNTY

INTRODUCTION

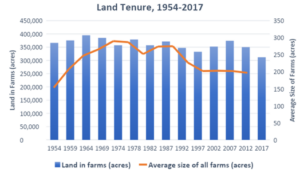

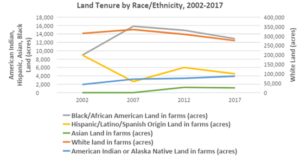

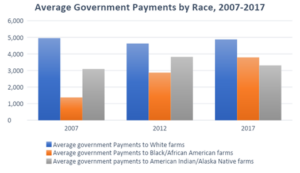

This research looks at land tenure trends down to the county level and examines what NASS data related to demographics and farm economics (government payments, gross and net cash income) can reveal as USDA endeavors to grow more farmers who feed US populations and sustain rural economies as well as contribute to a global economy based in agriculture.

In part, the impetus for this research project on Land Tenure has been the difficulty of finding data that can assist USDA in improving its services to small, limited resource, underserved farmers, and new farmers, ensuring the implementation of Farm Bill legislation.

During the research period (2022-2023), which corresponded with an unprecedented public health crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the intensification of climate related disasters, Rural Coalition and its partners have conducted direct relief, technical assistance and outreach with these hardest to reach and hardest to count farmer communities.

In this project, the research team purposively elected to conduct research alongside partners conducting legal and technical assistance related to land tenure, increased farm resilience and resolving heirs property and other land encumbrances in some of the most vulnerable communities and to use ground-level data to advance this project where data (and research dollars) were unavailable.

Across eight (8) Congressional Farm Bill debates, Rural Coalition and partners have encouraged USDA to collect race, ethnicity, and gender-related data about farmers (which was finally included in the 2014 farm bill), and we have advocated for funds to be appropriated for the upcoming TOTAL land survey as well as recommendations in the Equity Commission Report with respect to heirs property and a number of other evidence-based suggestions described elsewhere in our report.

THE USE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF NASS DATA TO THIS PROJECT AND FARMER COMMUNITIES WE SERVE

Employing the NASS/USDA suite of published Census of Agriculture data and online tools –including tables, quickstats, County and Race, Ethnicity and Gender (REG) Profiles– we began compiling project-specific profiles by county for our farm leaders to conduct a baseline assessment of farm economics as related to farmer demographics, current conditions and long term trends.

Because this research focuses on land tenure among underserved farmers, at least two major issues concurrently present the challenge and underscore the rationale for this research led by farmers themselves and the incorporation of their narrative interpretations of “what the data is telling us” about farmer realities (co-constructed as profile narratives and charts with the professional research team).

First, it is not surprising that many of the target counties (where partners conducted TA, Outreach, Education) had little to no NASS data that can be published without disclosing individual information. In NASS tables and publications, “(D)” indicates when this is the case for only part of the data. In NASS REG Profiles, there may be no information, which is indicated as, “Data not available at this geographic level for farms with Black or African American Producers.”

The second challenge arose when compiling data using more than one tool or aggregate dataset. Reconciling these data can be challenging due to recognized methods such as rounding, and changes to the Census questions over time. These challenges are compounded when, for instance, counting more than one operator per farm (and by multiple REG categories) results in a grossly different number of total farmers, which can also obscure whether farms are operated by a specified REG group. Again, the change from aggregating REG by principal operator in 2012 to farms with (multiple) producers in 2017 can obscure rather than illuminate the conditions for the most vulnerable farmers and farmland.

When we found the numbers too different to be useful or credible, we cross-checked using the total numbers of farms; the numbers of male and female producers; the number of female producers by race; etc. We used the most consistent, clear and comparable figures. In cases where there was little or no statistical data specific to the target population, the research team reviewed available data with farmer leaders to capture their “qualitative” insights about farmer realities, conditions, and trends.

What data is available when employing the NASS suite of tools shifts with evolving Ag Census questions, so the profiles produced for this farmer-researcher project may include the numbers of principal operators (2012), the count of all producers in 2017, or principal operators (2017). The Project Profile narratives below include notes about where data is unavailable and when tables (Census chapters) provided more, sometimes also incomplete, data. These notes document feedback about what is most useful for future census questions and the highlights NASS produces to projects such as this.

The charts produced for farmer-led research collaborators in this project combine some of the most useful features of the prior 2012 REG profiles and the current county profiles, especially the column focused on change since the last census, which is only available on county profiles.

Trends we gave a close look in research-specific profiles and interviews:

- Increase in farm size overall, concentration, profitability, government payments (showing participation in programs including conservation)

- Decrease in farm size for SDFRs and small sustainable family farm holdings

- Land tenure

- Land transfer

- New and Beginning Farmers

- Female farmers indicating land transfer to Female Principal Operators, New, Beginning, Next Generation SDFRs, Veteran Farmers

- REG groups for whom data is available

- Internet access for all and by REG - except when data is unavailable for groups at the geographic (county) level

DIVE INTO COUNTY DATA

STATE OF ALABAMA COUNTIES

The Yellowhammer State had 37,362 farms as of 2022. The decline follows a national trend. There are 1.9 million farms in the U.S., a 7% loss in just five years. In Alabama, 95% are still family farms or partnerships.

Barbour County Profile (data as of 2017)

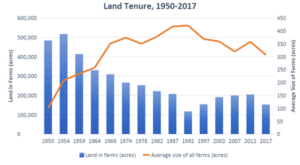

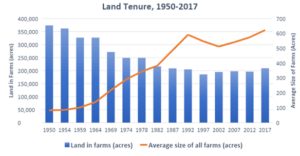

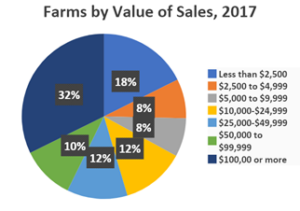

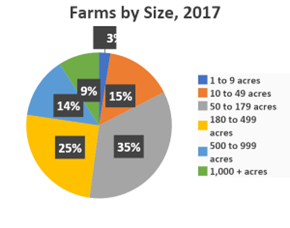

Barbour county Alabama is situated in the Southeast corner of the state and accounts for 2 percent of the state’s agricultural sales. Since 1950, Barbour has experienced an over 200 percent decline in land in farms with a 67 percent increase in average farm size. A consolidation of farmland can be observed in this county over time.

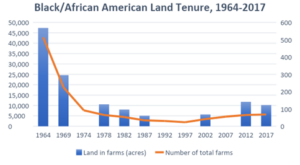

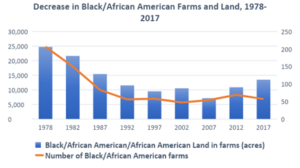

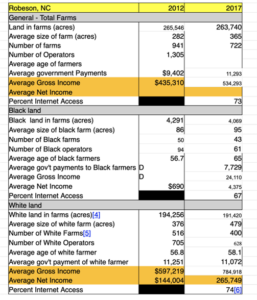

More specifically, Black/African American farms and land have experienced significant decline over the past 50 years. From 1964 to 2017, land in Black/African American farms decreased over 360 percent and the number of Black/African American farms decreased over 650 percent over the same period.

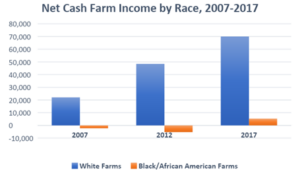

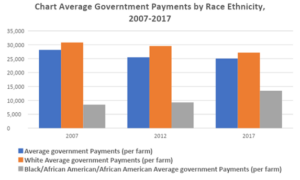

The loss of Black/African American farms is exacerbated by the lack of profits generated and government payments received by these farms in Barbour County. Compared to their White farm counterparts, who profited $46,851 on average per year from 2007-2017, Black/African American producers averaged -$784 per year in profits from farm sales. In addition, White farmers receive 37 percent more in government payments than their Black/African American counterparts. Compounding these disparities is a lack of internet service. Across the county, only 61 percent of farms are accounted as having internet access. Even less, only 46 percent of Black/African American farms have internet access.

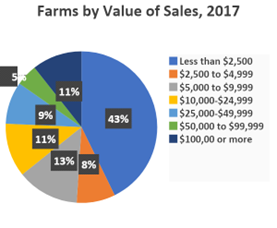

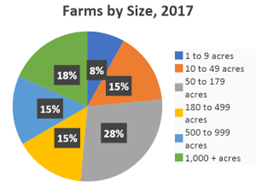

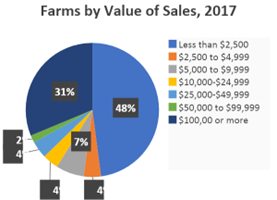

In 2017, the average farm size in Barbour County was 307 acres. On average, 81 percent of farms fall between 10-500 acres. Although these farms might range larger in size, 43 percent of farms make less than $2,500 in agriculture sales per year. From 1992-2017, the poultry and egg sector has dominated the market value of agricultural production across the county, averaging over 70 percent of total production. Cotton and cattle follow far behind, but also make up 7 and 4 percent of the total agricultural product sales in the area.

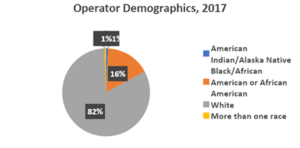

Most producers in Barbour County are White, but there is still a significant portion of Black/African American farmers, 25 percent of which are New and Beginning farmers. The average age of producers in the county is continually increasing and stands at 60.5 years old in 2017. On average, African American/Black producers are younger than White producers with averages ages of 58.3 and 60.8, respectively.

Geneva County Profile

In 2012 in Geneva county, farm size went down by 8%, land in acres diminished to 218,805 acres, but average farm size went up by 8% to 215 acres.

Most 2012 REG data was unavailable at the county level for 2012, but for female producers. In 2012, female farmers operated 157 of the 1017 farms with producers in the county. They were 66.7 years old on average, with gross average earnings of $111,840, net cash farm income of $19,949, and government payments averaging $6205 (where the total avg payment was $,7,876).

REG Data are not available at this geographic level for farms with Asian; Black or African American Producers; Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino Operators (Project Profiles used census chapter tables, county profiles and REG estimates.]

The 2017 REG Profile shows that there were 30 American Indian farms, and white farmers counted as 806 out of 820 farmers. 424 (white) women were farming on 427 farms with an average age of 60.6.

While no 2017 REG for other groups at this geographical level, the tables show that there were 12 farms with Black producers in 2012 and 2017. The number of producers captured by the 2017 multi-producer question showed an increase to 15, but their total farmland decreased from 1472 to 711 acres.

In 2017, 1227 white producers farmed 180,864 acres on 711 farms, which also reflects a trend in concentration. In the prior census of 2012, 1421 white producers on 996 farms operated on 216,504 acres.

STATE OF GEORGIA COUNTY

Baker County Profile

In 2017, all 147 farms in Baker County operated on 130,989 farmland acres averaging 891 acres. In 2012, 150 farms in the county amounted to 146,478 acres with an average of 977 acres. In 2007, there were 156 farms on 135,181 acres with an average of 867 acres.

While most of the REG data is masked (D), in 2017, 33 Black farms on 6291 acres averaged 191 acres in size, including two with over 1000 acres.

Much of white producer farmland data is also masked (D) in the 2017 REG profile, but farm size data shows that 30 (28%) were over 1000 acres. In 2012, 158 white producers farmed on 112 operations with a total of 137,874 acres. The 108 farms in the county with 142 white producers, on average grossed $426,226 and netted $158,679 in cash income with $76,022 in government payments. All farms averaged

Women producers netted slightly higher than average income of $158,679 with an average gross (MVP) of $426,226 and $76,022 in government payments.

In 2017, whereas Black farmers’ average age was 66.1, white farmers were 60.7 on average. On farms with a total of 48 female producers, including 36 white, one American Indian, 4 Asian, and 7 Black producers, women producers were 63.2 years old on average.

Internet access for Black farms was significantly low at 30% in 2017, while 75% of farms with white producers and 72% of farms with female producers had access.

Update: In 2022, overall farm size increased by 20% in Baker. While the total 113,062 acres in farms and the number of farms, 1067, have decreased by 14% and 28% respectively. Average net cash income of $84,096 was down 37%. Gross was $555,624, with government payments of $36,727. (Only 65% of all farms have access to the Internet.)

Dougherty County Profile

In 2012 there were 26 farms with Black operators in Dougherty County, the 2017 census counted 37 producers. In 2017, 67 African American producers, 24 of whom were women, farmed on 2872 acres, but 2012 data is unavailable for comparison. The average Black farmer was 66 years old, received a government payment of $8,567, and 73 percent had internet access.

In 2017, the average gross income for all farms in the County was $162,519, net income of $162,519 with government payments of $30,022. The 90 farms with white operators lost acreage in 2017, going from 90 to 71 farms with 127 operators (4 fewer than previously) and from 63,193 acres to 61,570.

In 2022, the average farm size was 546 acres, down 7%, and the net cash income averaged 16,962, which was a 90% decrease.

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA COUNTIES

OVERVIEW - NC is 15th in the nation in the loss of farmland from 2017 to 2022, although those numbers don’t reflect the population growth and development the state is experiencing now or is projected to see in the next 16 years. (American Farmland Trust ranks NC second in the country in projected land loss by 2040.)

The number of new and beginning producers was up 13 % from 2017, just shy of 23,000 new and beginning producers in agriculture.

The average age of farmers in North Carolina remained at 58.1 years. (Young people choosing to farm.) Largest number of farms in Randolph, Chatham, Buncombe, Johnston and Duplin counties.

Granville County Profile

Project population - African American Producers

ALL FARMS - In 2017, Granville County had 557 farms on 124,813 acres with an average farm size of 224 acres. Despite the new all producer census question, farmers went from 855 operators to 844 producers. Their average age was 59.7. Farm income averaged a gross of $49,268 (up from $38,769 in 2012), with an average net cash income of $9033, and an average of $1712 in government payments. Farm access to the internet averaged 79 percent.

BLACK FARMS - Between 2012 and 2017, farms with African American producers decreased in number from 35 to 24 farms, previously an average size of 86 acres on a total of 3067 acres, average size was not published for the current 2762 total acres of Black farmland in 2017. Economic data is spare for 2017, but in 2012, African American farmers were netting an average cash income loss of $6818, grossing $12,010, and had an average in government payments of $693. (Internet data is masked along with other economic (farm asset) data by demographic at this geographical location.)

WHITE FARMS - While the average size of farms with white producers was not published for 2017, farm acres increased to 122,525 acres and the number of farms decreased from 549 in 2012 to 532 farms. Previously, these farms covered 97,283 acres, and the average sized white operated farm was 177 acres. Economic data is also published sparingly for this demographic in 2017, but in 2012, white farmers were netting an average cash income of $4818, grossing $40,829 with $4542 in government payments. (Internet data is masked along with other economic (farm asset) data by demographic at this geographical location.)