Final report for NCIN22-002

Project Information

2023-2024 Indiana state initiative topics

- Structural Support for Food and Agricultural Systems

- Crop Diversification Practices to Enhance Regenerative Agriculture and Food Systems in all scales of agriculture

- Integrated Approach to Natural Resources

- Addressing the Needs of Underserved Farmers - Land Access and Ag Land Conservation

- Local Foods with Disruptions

Initiative 1: Structural Support for Food and Agricultural Systems

Several synchronized initiatives are taking place in Indiana for holistic food system change. However, there is a need to increase the capacity and diversity of leaders working together for Indiana's more robust, equitable, and resilient food system. We know that professional development and leadership training for food systems changemakers is an impactful approach to addressing our needs. We seek to address this in the short and long term. Several of our current leaders in the Indiana food system have attended the Wallace Center’s national Food Systems Leadership Network Training and find that this was one of their work's most impactful professional development experiences. We intend to bring this training to Indiana and embed long-term support for Indiana food systems leaders within the Partners IN Food and Farming organization (PIFF). Along with developing confident, diverse, and networked food systems leaders for Indiana, we will focus on these primary outcomes:

- Lead with equity – not an add-on and not optional. Equitable processes and diverse leadership throughout the state will ensure initiatives are led and organized with food equity at the forefront and a collective long-term vision for food justice for farmers, eaters, and the businesses and organizations working in the social, environmental, economic, and justice-oriented work for food systems.

- Focus on systemic change, the symptoms, feedback loops, and power structures that maintain racist and inaccessible systems.

- Provide ongoing connection and convening events to inform a statewide push for investment and policy changes for Indiana’s food system.

- Host a set of tools for trained leaders to utilize in their geographically local leadership roles.

Activities:

- Plan and implement a Food Systems Leadership (FSL) training for Indiana. Invite food systems leaders to apply, attend and complete a 2.5-day training program. Attendees will commit to leading the 2024 food systems leadership training and years after that.

- Create and maintain resources for leaders, including informational materials, ongoing communication and networking, and training to ensure best practices for leadership in the food system.

- Assemble the first two cohorts of food systems leaders in a symposium to discuss the next steps

Expected Outcomes:

Short term:

- Ten food systems leaders will attend training to participate with the intent to lead in year 2

- Food system leaders will contribute to and utilize a database of resources

- Food system leaders will continue in a community of practice for the FSL network for Indiana

- Gather trained food system leaders to discuss needs, and next steps for the network

- Food system leaders will have identified networks from where they represent/gather information

Intermediate:

- Ten food system leaders trained in year one will lead food system leadership training in year 2

- The new cohort of food system leaders will connect and build capacity for improved ways of communicating, understanding, and developing food systems.

- Relationships of trust and communication will be established among food systems leaders in Indiana

- Food system leaders will identify funding, resources, and support organizations for long-term support

- Food system leaders will have networks from which to gather information on priorities, issues, and challenges in the Indiana food system

Long term:

- We will establish an Indiana Food Systems Leadership training that will operate annually, led by PIFF (Partners IN Food and Farming) nonprofit

- Each year 5-10 new food systems leaders will emerge to grow the pool of leaders trained in food justice and regional approaches to food system development.

- Food systems leaders in Indiana will access information, resources, and each other for support in their work.

- Food systems leaders will have a mechanism to gather information to help inform coordinated advocacy and education of decision-makers at the local, regional, and state levels.

Initiative 2: Crop Diversification Practices to Enhance Regenerative Agriculture and Food Systems in all scales of agriculture

Educators need the training to support the diverse needs of Indiana farmers and landowners. This encompasses context-specific principles at the farm level with diversified crop and livestock systems and landowner engagement.

Activities:

- Training offered by Midwest Mechanical Weed control field day

- Training at UNL’s Flame Weeding Workshop

- Dry Bean Variety Trial Year 2

- Jessie Frost farm field day bus tour - learning about succession and crop rotations

Expected Outcomes:

Short term:

- 14 Ag professionals will benefit by gaining real-world experience with mechanical weed control equipment and networking with researchers, other professionals, farmers, and tradesfolk (especially those running the demonstrations).

- 14 Ag professionals attending this trip will gain practical knowledge about flame weeding equipment and practices that will expand their ability to assist organic row crop clients, particularly beginners.

- 30 Ag professionals will increase their knowledge about dry bean crops in Indiana.

- 15 Ag professionals know intensive succession planning and management into farming systems using cover crops and extended cropping rotations.

Intermediate:

- After the field days, educators will share knowledge with their stakeholders.

- Discussions in regional updates inform educational gaps and assist in delivering training.

- Participants will develop programming to transfer knowledge to producers.

- Extension Educators, Agriculture Teachers, and Extension Specialists will instruct on the different ways to incorporate regenerative/holistic farming.

Long term:

- Intensive and diversified farmers will have more viable farms based on adopting sustainable agriculture practices.

Initiative 3 - Integrated Approach to Our Natural Resource

Indiana remains a leader in soil health practices and cover crop adoption. The various levels of knowledge across the state require a tiered training program for professionals and specialized training for specific production models. Each program focuses on the environmental and economic sustainability of soil health practices while touching on the social aspects of these practices.

Activities:

- Intensive on-farm workshop no-till farm in Portland Maine

- Intro to Soil Health Workshops

- Core Soil Health Systems (6 virtual sessions and 2 in person)

- Continuing Soil Health Educations (1 year virtual; 1 year in person in 4 locations)

- Soil Health and Sustainability for Midwestern Field Staff

- NWF Grow More Training (Conservation Communication) 4 trainings in two years (8 total)

- Presentation and Media Skills Development – 1 training

- Conservation PARP topics created for ag professionals to use with farmers

Expected Outcomes:

Short term:

- ~100 ag professionals will increase their knowledge of reduced soil disturbance, increased residue cover, increased biodiversity, and year-round living roots on soil health. They will learn of the various benefits, uses, and management of cover crops.

- ~100 ag professionals will increase their knowledge of the various benefits, uses, and management of cover crops (specialty and commodity crop systems) using prescribed cover crops.

- 15 ag professionals learn about no-till organic intensive growing practices

- 50 ag professionals improve their communication skills with middle adopters of conservation practices.

- 50 ag professionals improve their presentation and communication skills.

- 5 Conservation PARP topics will be created to use in the Purdue Pesticide Programs library that meets the requirements of OISC and share conservation topics.

Intermediate term:

- Local educators will transfer their information and knowledge to other educators, conservation staff, ag students, and local farmers.

- Information sharing through the network in newsletters, blogs, news releases, and local/ regional meetings, as well as in developing conservation plans to address specific resource concerns.

- Through improved communication skills, local educators will be more effective in their outreach and education efforts. They will also share techniques with other local staff.

- PAC staff will integrate cover crops and/or reduced tillage into standard production practices at their center.

Long term:

- Farmers will have more viable farms based on adopting sustainable agriculture practices.

- Indiana’s Conservation Practices will show more conservation practices being used each year.

Initiative 4: Addressing the Needs of Underserved Audiences in Agriculture – Land Access and Ag Land Conservation

Land access is the biggest hurdle to beginning farmers nationwide. Beginning farmers in Indiana struggle to find and afford farmland in urban and rural settings (based on Marion County needs assessment).

Activities:

- Land Access and Land Conservation in Indiana – Community of Practice Kick-Off Event

- Community of Practice Monthly Meetings (virtual and two in person)

- Community of Practice Ending Farm Tour and Facilitated discussion to ID action for the next 2-3 years

- Strategic Doing Training

Expected Outcomes:

Short term:

- We will bring together 30 Ag Professionals whose work involves land use to learn about solutions that can help beginning farmers.

- Identify resources, ag professionals, and other partners in the land access and ag conservation area.

Intermediate:

- Together, we will form a "Community of Practice" to learn what other states are doing to improve farmland conservation and access for beginning farmers in urban and rural areas and explore what strategies might work in Indiana.

- We will meet monthly for a year, including two in-person meetings.

- Following this learning intensive 12-month period, 3 ag professionals will be trained and learn how to use the Strategic Doing structure to identify and make progress on 2-3 concrete, collaborative farmland access, and conservation projects.

Long term:

- Reporting on the progress of the 2-3 concrete, collaborative farmland access and conservation projects that spin out from this initiative.

Initiative 5: Local Foods with Disruptions

Justification: There is increasing activity at the city, county, and state levels to understand and implement community food policies and programs to address disparities in equity, access, health, profitability, and community resilience to climate change. However, discussion, programming, and funding can and do take place without community capital asset mapping and the knowledge of existing food policies. Tools to identify and map food system climate resilience indicators have been scattered. From 2019-2022 a group of food systems leaders, supported by the North American Food Systems Network (NAFSN), created the CARAT - Community Agricultural and Resilience Audit Tool for self-defined jurisdictions to examine, inventory, discuss and quantify the policies, activities, and actions. The tool is comprised of seven (7) themes for an authority to examine, including 1) Agricultural and ecological sustainability; 2) Community health; 3) Community self-reliance; 4) Distributive and democratic leadership; 5) Focus on the farmer and food maker; 6) Food justice; and 7) Place-based economics.

Activities:

- Design and deliver one-day training for extension educators, other food councils, and grassroots organizations to utilize the tool.

- Work with five groups in Indiana, delivering geographically oriented support for the tool with their local jurisdiction(s).

- Gather feedback and information from jurisdictions and tool users to enhance the quality of the CARAT.

Expected Outcomes:

Short term:

- Five groups in Indiana will attend, learn and take home CARAT tool knowledge and plan for assessment

- Five groups will conduct an assessment within a 6-month window

- Five groups will re-convene to share findings

Intermediate:

- Extension educators, grassroots organizations, and political jurisdictions will work together to gather information and assess their strengths and weaknesses in the food system when facing climate and social disruptions.

- Five groups in Indiana will reconvene to learn from each other and give feedback on the CARAT tool.

Long term:

- Extension educators and grassroots food system leaders in five geographic locations will have clarity on where funding, programming, and policy resources can be most impactful for creating a resilient food system

Evaluation will be used to measure progress toward each of these outcomes. An annual survey asks ag professionals how many people they reached out to with their knowledge gained, and they also share their qualitative observations.

Indiana will continue to move toward the implementation of sustainable agriculture practices. Indiana is a leader in adopting cover crops and other soil health-promoting techniques, integrated pest management strategies, pollinator protection practices, urban farming, diversified farming systems, and local food production. The following initiatives were identified, discussed, and approved in 2022:

- Structural Support for Food and Agricultural Systems

- Crop Diversification Practices to Enhance Regenerative Agriculture and Food Systems in all scales of agriculture

- Integrated Approach to Natural Resources

- Addressing the Needs of Underserved Audiences - Land Access and Ag Land Conservation

- Local Foods with Disruptions

SARE in Indiana is successful because of formalized collaborations committed to conservation and sustainable agriculture practices. A primary goal is to expand the communication with these groups and to identify others in Indiana to foster additional cooperation in program delivery. We have increased our outreach to the staff at other institutions, organizations, and farmers who are interested in sustainable agriculture practices. The Indiana Small Farm Conference, the Urban Soil Health Initiative, and our conservation partners will continue to serve as a means of outreach to a previously largely underserved audience. We will also continue collaborating with national and state organizations in soil health and cover crop systems.

Advisors

Education & Outreach Initiatives

Several synchronized initiatives are taking place in Indiana for holistic food system change. However, there is a need to increase the capacity and diversity of leaders working together for Indiana's more robust, equitable, and resilient food system.

We know that professional development and leadership training for food systems changemakers is an impactful approach to addressing our needs. We seek to address this in the short and long term. Several of our current leaders in the Indiana food system have attended the Wallace Center’s national Food Systems Leadership Network Training and find that this was one of their work's most impactful professional development experiences. We intend to bring this training to Indiana and embed long-term support for Indiana food systems leaders within the Partners IN Food and Farming organization (PIFF).

16 Extension Educators were trained and equipped to use as Junior Master Gardener curriculum

Promoted, participated in, and financially supported the Black Loam conferences (meaning rich soil and focusing on BIPOC farmers to grow the community and learn about resources available to them and their farms) across Indiana to share SARE resources with the participants. Across 5 cites in a couple of months in Spring 2023, 225 participants came to learn and network.

Promoted, participated in, and financially supported the Small Farm Conference in Hendricks County, in March 2023. also, hosted CANI training with Janelle White to share about Diversity Equity Inclusion and our language. 189 people attended the conference and about 30 ag professionals and farmer leaders attended the CANI training.

Promoted and financially supported ABC's of Organic Ag Workshop Bloomington, IN August 2023 where a teacher from Columbia came to teach 42 students (ag professionals and farmer leaders) about bokashi composting. One of the students is a Master Gardener who is using bokashi to try to remedy a salinity issue in demonstration garden beds. This Master Gardner shared in a educational meeting to 30 other master gardeners and will continue to share knowledge with others. She wrote this with bold that will help her in her Master Gardener volunteering, "

The first note I took at the conference, “The ABC’s of Organic Agriculture”, at Sobremesa Farm in Bloomington, was one by world-renowned presenter, Jairo Restrepo: “The basis of organic agriculture is soil.” He went on to say that soil is life, so we must give back to the soil which provides for us.

As Restrepo said, “The more minerals that are in the soil, the more biodiversity the soil has.” He explained that minerals can be present in the soil, but these must interact sufficiently with other minerals. This interaction occurs (in great part) through the aid of microbes, hence the importance of biodiversity for the health of the soil and for the health of any plant that is growing in it. With this premise established, Restrepo encouraged conference attendees to separate “agriculture” from “agribusiness.”

Restrepo used the Japanese composting method, “Bokashi”, in his soil preparations, such as compost that is specific to the problems of a growing crop, or in recipes for liquid biofertilizers (“teas”.) Bokashi is a form of composting that utilizes fermentation to speed up the process of a traditional compost. Restrepo demonstrated how to make, from scratch, the essential ingredients used in the Bokashi fermentation process and he added the Bokashi elements to his various compost recipes.

Though Restrepo focused on creating compost used in farming, any of his recipes could be used in a larger garden, as many recipes were crop-specific. The teas were often targeted at getting rid of specific pests, so those could be used in a garden as well. Though many of the members of the Hancock County Master Gardeners Association are not organic farmers, they could gain an appreciation of the Bokashi method by utilizing a few of Restepo’s compost recipes in their gardens.

In addition to sharing a few of these recipes, I could reiterate to the members the importance of soil testing. As Restrepo informed, “a soil can be rich in organic matter but still lack essential microbes.” Restrepo suggested taking three soil samples: one at 50 cm, one at 25 cm, and one along the top edge of the testing site. These three samples will better reveal the “history” of the soil. The more information that one can gain about the soil, the better prepared one will be to create a compost specific to the soil’s and the plant’s needs. He suggested sending the soil samples to a lab that will not only identify the minerals present or lacking but that will give a microbial analysis as well (such as Earthfort.)

Restrepo also led a workshop that taught attendees how to conduct a chromatographic analysis of the soil. I could share the basic concept of this type of visual analysis and offer a couple of book titles for learning more about it. Basically, the three areas of color on the results sheet indicate the elements (and aeration), the microorganisms, and the enzymes present or lacking in the soil. As Restrepo said, “To discuss agriculture, we need to understand chemistry.”

Though Restrepo did not address the Bokashi method of turning kitchen scraps into compost, the farming compost principles share the same basic premise: Chelates, which are not available in soil, can be made available via the fermentation process. These chelates are important to the soil’s mineral compatibility.

While at the conference, I met an organic farmer who uses the kitchen scrap method on his farm. I recorded a brief interview with him and I could share this “testimonial” with the membership. Through my own research and practice, I can inform the membership about how to practice the Bokashi method of kitchen scrap composting.

I learned a great deal from the conference speaker who is a master of chemistry! As a Professor of Agriculture from the University of Kentucky said, “Organic farming in the US is on a spectrum. Jairo Restrepo is on the deep, profound end of the spectrum.”

We are working with the Wallace Center to create a food systems leadership retreat in fall 2024. The Indiana Department of Health will likely be increasing the investment from SARE, so we are excited to have a good budget to do it right. We are meeting with leadership again in February to go through how they might support us and what the retreat would look like.

110 Ag Professionals trained in Diversified Food and Farming systems - May 2023, a tour to a Food Stop and a farm food stop in Bloomington Indiana. October 2023, Indianapolis Urban Farmers tour with discussing land access.

18 farmer leaders and ag professionals trained at Sobremesa farm on “Workshop Series 2024: The ABC of Organic Agriculture, Chromatography and Sustainable Livestock Management by Jairo Restrepo”

One participant shared:

The ABC’s of organic agriculture, chromatography, and sustainable livestock management workshop was nothing short of amazing, Jairo Restrepo’s information is one of the easiest to digest, the way he explains every method and concept is easy for anyone to understand, not only does Jairo talks, he also allows us to be hands on, something that helps us learn faster, by doing the work.

As a farmer for our small farm Common Ground Cultivation LLC in Brokeville, MD, we have started to implement the use of bokashi in our soil or as blends for our rows and raised garden beds, working with bokashi over the last year, has allowed us to use zero fertilizer in our first two seasons, improving our soil structure greatly. With the new information on biologicals we are working on making a few of the liquids to apply as fertilizers this 2025 spring and moving forward, the work that was taught has become so essential that w are starting to speak out in our communities and to other farmers about all the benefits on learning this systems, how beneficial it is for our soil health, with the aim of having soil sovereignty to grow healthy delicious crops. Moving forward the implementations of various liquids to organically help our plants fight disease, pests, and grow healthy, will be prioritized over the use of anything synthetic or that can hurt our soil Biome. I wholeheartedly recommend to anyone thinking to take the next step in their journey, of good farm practices and management for our soil health, to come to one of Jairo’s workshops and his team. Every single member is knowledgable and friendly and always ready to answer any questions.

Kind regards, Hades “rey” Lestary Farmer and Co-owner of Common Ground Cultivation LLC

Another farmer couple who participated stated, that "attending Jairo Restrepo's conference was a very enlightening experience. Jairo, a renowned agronomist, agricultural engineer, and worldwide lecturer, brought his extensive knowledge and over 40 years of experience to the forefront, impressing us with his insights and practical wisdom.

The workshop was a perfect blend of theory and practice, engaging us in the key concepts of organic agriculture. Jairo's lectures and discussions on soil recovery and food quality were both informative and inspiring. The hands-on demonstrations were particularly valuable, teaching us how to produce our own organic fermented fertilizers (bokashi), prepare liquid biofertilizers, and reproduce beneficial soil microbes on our farms. Additionally, we learned how to prepare mineral broths for disease and insect control, all while leveraging local resources and materials.

Jairo's ability to convey complex ideas in an accessible and engaging manner made the workshop an unforgettable experience. His passion for organic agriculture and commitment to sustainable practices were evident throughout the conference. We left with a wealth of knowledge and practical skills that will undoubtedly benefit their farming practices.

Overall, Jairo Restrepo's conference was a resounding success, and we highly recommend it to anyone interested in organic agriculture and sustainable farming techniques."

SARE supported the IEEA (Indiana Extension Educators Association) professional development conference, specifically a Circular Economy class with Jennifer Russell, PhD Virginia Tech. 127 Extension Educator and specialists attended the professional development conference

26 Extension Educators were trained at the Diversified Food and Farming Systems professional development - From a participant: Food safety training focusing on post-harvest safety. I spent a great time in the Purdue soil lab. Learned about wine production. And then I got to climb up a tree and learn about urban forestry.

May 2024 St. Mary of the Woods, Terre Haute, IN 13 Extension Educators received Professional development and tour of the farm and grounds https://spsmw.org/about/justice/white-violet-center-for-eco-justice

Offshoots Training for Grow More Ag Professionals 2 Indiana participants went to St. Louis for in-person training from the National Wildlife Federation to be able to train ag professionals in Indiana with the online pilot educational program NWF had for a couple of months.

October 2024 - 2 Travel scholarships for ag professionals to Kheprw Field Day with Black Loam and University of Kentucky - learned about Urban agricultural resources in Marion County and networked with farmer leaders and ag professionals.

Educators need the training to support the diverse needs of Indiana farmers and landowners.

This education encompasses context-specific principles at the farm level with diversified crop and livestock systems and landowner engagement.

3 ag professionals trained at Midwest Mechanical Weed Control field day in Wooster, Ohio Sept 2023

There is no better place to see a huge variety of mechanical weed control equipment than this field day. The event serves both vegetable growers and grain producers at large and small scale – there is literally something for everyone. Hand tools, two-wheel tractors, large row crop cultivators, and autonomous tools showed off their capabilities in crops specifically planted for the field day. Farmers from across the US and Canada attended this year’s event. It’s a great place to meet other growers using a more “mixed methods” approach to weed control, or those that are farming fully organically.

The Land Connection makes an effort to host this event in a different state each year. I attended this same event last year at Michigan State’s Southwest Research and Extension Center near Benton Harbor, a site focused on vegetable research with profoundly sandy soil. I was enamored with the variety of tools and opportunities to talk directly with equipment dealers and manufacturers. But I was still curious to see how the tools I saw would perform in less-forgiving soils. Luckily, Wooster’s soils are just what I needed to see! Heavier-textured silty loams, with a few rocks here and there, gave the tools on display a bigger challenge.

Wooster did not disappoint. Some tools performed better than I would have expected in the heavier soils on-site, including the whisker-weeding hand tools. Most tools called for different depth adjustments in heavy soils compared to sandy soils since there is a higher risk of burying small seedlings and creating compaction with stickier soil. Many tools have different setup suggestions for different soil textures and crop conditions – at this event, you can ask the equipment reps or your fellow farmer for suggestions on how to improve the tool’s performance.

The higher-tech tools, like the Carbon Robotics laser weeder, are generating a lot of excitement but aren’t practical or affordable… yet. But it sure is exciting to see a laser vaporizing palmer amaranth and barnyardgrass seedlings into thin air.

Tools on display included the following:

Vegetable crops

- BCS implements – rototiller, power harrow, V-cultivator, plastic mulch layer, flail mower, rotary plow, sickle bar mower, utility trailer

- Carbon Robotics autonomous laser weeder

- Garford in-row camera-guided cultivator

- Magic cultivator and whisker weeder wheel hoe

- Q-hoe whisker weeder

- Planet Jr. antique walk-behind tractor and cultivator

- Sutton Ag camera-guided cultivator

- Terrateck Cultitrack + KULT-Kress cut-away discs

- Terrateck edge-of-plastic brush weeder

- Thiessen rear-mounted steerable cultivator

- Tilmor 520Y with basket weeder and Einböck tine weeder

- Tilmor Power OX 240 walk-behind tractor with tender plant hoe, finger weeders, spring hoe weeder, Thiessen tine weeder, and basket weeder

- Accura Flow cultivator

- Hatzenbichler Air Flow tine harrow

- Henke Buffalo 6400 cultivator

- LEMKEN Rubin speed disc

- Einböck Chopstar camera-guided cultivator

- Einböck Aerostar Fusion tine harrow

- TH Fabrication Swinging Spider cultivator

- Treffler tine harrow

- Rotary hoe (with retrofitted Ho-Bits spoons)

I think there is no better substitute for seeing how a tool works than getting in the field with it. If you’re interested in attending the Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Field Day, expect to see it scheduled in mid-to late-September. You can check back with The Land Connection in the summer of 2024 or keep an eye on your Purdue Extension newsletters for the program advertisement!" Ashley Adair Organic Specialist Purdue Extension

Dry Bean Variety Trial Year 2

Dry Bean Research Summary 2023 – Exploring Large Grains on the Small Farm

By Ashley Adair, Extension Organic Agriculture Specialist

Introduction (from 2022 summary)

Many farmers, especially beginning farmers, plan their farms around producing a variety of perishable products that sell well, like tomatoes, peppers, and leafy greens. As farmers gain more experience and build their markets, they may begin to wonder what other crops they can add to their crop rotation. Storage crops can be part of that plan, allowing them to extend their sale season and provide additional value to their customers. Storage crops might include winter squash, onions, and pumpkins. Another storage crop to consider is grain: flint corn, popcorn, wheat, or even dry edible beans, which are the focus of this project.

Stepping into the world of grain might seem daunting at first. The farmer might assume they need a lot of land, a combine harvester, large tractors, and complex planting equipment to ensure success. This project aims to dispel preconceived notions about grain production on a smaller scale and explore ways to make small scale grain production viable for the small scale grower. This project also seeks to discover which heirloom dry bean varieties are suitable for production in Indiana.

What are dry edible beans? (from 2022 summary) Dry edible beans, or simply dry beans, are a food grade storage grain crop. Dry edible beans come from the same type of plant that many fresh edible beans (i.e. green beans, or fresh shell beans) come from, Phaseolus vulgaris. There are many varieties of beans available, and some varieties can be grown either for fresh or dry. They are most commonly grown as a food grade crop, and provide many nutritional benefits to those who consume them. That being said, they can also be incorporated into animal feed, but are more lucrative in the food grade market, selling for as much as $60 per hundredweight (cwt) in the certified organic marketplace. Compare this to certified organic soybeans, which have sold for $35-40 per bushel in 2022, and require a growing season as many as 20 days longer to mature.

Dry beans are a shorter-season crop, usually taking 80-90 days from planting to harvest. They prefer well-drained soil and are generally poor competitors with weeds. In organic management, dry beans require vigilance and much attention focused on mechanical weed control. Foxtails and other grasses are public enemy number one for this crop, but any weed will be problematic for growing these successfully. On the other hand, dry beans are a legume and can provide for much of their own nitrogen needs, even in soils that have relatively low organic matter, like the sandy soils where they prefer to grow. Dry beans are most commonly grown in the north-central states of the US, as well as Ontario, Canada. The number one producer of dry beans in the US is North Dakota, followed by Michigan, Nebraska, and Idaho. While these states are different from each other in terms of climate and weather patterns, they share some combination of suitable soil types, rainfall amounts, grain handling infrastructure, and shortened growing seasons that make growing dry beans (versus soybeans) a viable option for the commercial grain grower.

Many of the commercially available dry beans at the grocery store are limited to a handful of specific varieties. Commonly available to consumers are pinto beans, black beans, great northern beans, and kidney beans. But there are a huge number of dry bean varieties available to the small scale grower and market gardener that can’t readily be found at the grocery store. These varieties often are locally adapted to where they were bred, rather than bred for adaptability to a large geographic area or mechanized harvest. In addition to local adaptability, each dry bean has specific flavor, culinary characteristics, and cultural history that can help enrich the farmer’s and consumer’s kitchens while providing essential nutrients, such as fiber, protein, and several minerals, to the human diet.

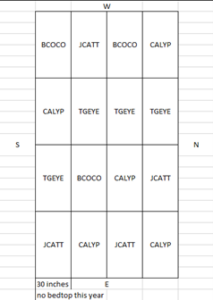

Project description and design (2023): A dry edible bean variety trial was installed at the Purdue Student Farm (West Lafayette, IN) and Pinney Purdue Agricultural Center (Wanatah, IN). Each site was planted in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) (see figs 1 and 2).

One of the largest differences between the two sites is soil type. The PSF features a silty clay loam, and Pinney PAC features a sandy loam. Other differences include cropping history and weather conditions. The PSF has been an organically managed (not certified), diversified vegetable farm since 2016, whereas the research plot used at Pinney PAC has been left unused and untreated for several years prior to the installation of this trial – which means a large weed seed bank. The trial was designed as a randomized complete block trial, meaning each “column” of the trial will feature all four varieties, randomly arranged. This type of design is common in agricultural research and helps to account for variability in the field where the trial is planted. Varieties used in this trial include the following:

- Black Coco – a type of black bean (determinate bush-type)

- Calypso – a type of black bean (determinate bush-type)

- Jacob’s Cattle – a type of kidney bean (determinate bush-type)

- Tiger’s Eye – a type of cranberry bean (indeterminate upright-type)

Varieties were selected based on several characteristics, including time to maturity, cultural relevance to the Midwest, common cooking preparations, and growth habit.

Figure 3. Plot layout at PSF in 2023. This plot layout reflects actual planting, which due to a miscalculation, resulted in 5 reps of CALYP and only 3 reps of BCOCO.

Materials and Methods

Each variety was planted using an Earthway seeder fitted with a pea plate in a double row at each site in 2022, each with about 18 inches of spacing between rows. Each block was 12.5 feet in and beans were seeded approx. 2” apart using a Jang JP-1 seeder fitted with a bean plate. Both sites were irrigated as needed using plastic drip tape in 2022, to the equivalent of about 1 inch of rain per week. At PSF, beans were grown on shaped beds about 4 inches high. Hand labor was used to weed the beds. In 2022, each trial was side-dressed when bean plants had fully unfurled their second set of true leaves using an OMRI-listed pelletized poultry manure to the equivalent of 40 lbs. N per acre using an Earthway seeder fitted with a pea plate. In 2023, no bed-tops were made, 4 single rows 12.5 ft. long per block were planted, only overhead irrigation was used at PSF, and neither trial was side dressed, assuming enough N credit from the previous fall’s cover crop planting of about 40 lbs N/acre. Weeding was done by hand with hand tools and a wheel hoe fitted with an 8 inch blade.

In 2022: At PSF, the trial was planted on 6-3-22. Pinney was planted on 6-10-22, and due to inadequate irrigation, had to be replanted on 6-24-22. PSF was harvested over the course of several days beginning 9-6-22. Pinney was harvested on 9-20-22 and 9-22-22. Harvest can take place as soon as dry bean pods are about 85% yellow and 15% brown, or when beans split in two when smashed with a hammer.

In 2023: At PSF, the trial was planted on 5/25. At PPAC, the trial was planted on 6/8.

Dry beans must be threshed and winnowed in order to prepare them for weighing and sale. For the purposes of developing recommendations and materials for demonstration, two threshing methods were used in 2022. Manual threshing was completed by flailing bean plants against the inside of a 55-gallon food grade plastic drum. Mechanical threshing was done using a Swanson Machine Co. portable gas powered plot thresher (see figs. 3 and 4). In 2023, all beans were threshed mechanically with the Swanson unit.

Figure 4. Manually threshing whole dry bean biomass using a 55-gallon drum.

Figure 4. Manually threshing whole dry bean biomass using a 55-gallon drum.

Figure 5. Swanson Machine Co. portable plot thresher being fed whole dry bean biomass.

Figure 5. Swanson Machine Co. portable plot thresher being fed whole dry bean biomass.

Each method presented advantages and disadvantages, namely time commitment (hand threshing took as much as 10 times longer) and expense devoted to purchasing and maintaining a machine (threshing machines can cost upwards of a few thousand dollars).

Whether threshed mechanically or manually, all dry beans still needed to be winnowed. Winnowing takes place by either using mesh screens or moving air to separate dry biomass from the beans themselves. In this case, moving air was the method used, to help simulate conditions and equipment available to a small-scale grower. A garage fan and solid-bottomed harvest bins were used. Video footage was procured from this process in order to instruct prospective growers further (available upon request). Fig. 5 shows part of this process.

Figure 6. Winnowing Calypso variety using a garage fan and harvest bins. Chaff is separated from beans while pouring biomass material from one bin into the other. Process is repeated until beans are reasonably free of chaff.

After harvest, the Purdue Student Farm site was flail mowed and power harrowed using a BCS walk-behind tractor and corresponding attachments. A cover crop mix including cereal rye and hairy vetch was seeded at the Purdue Student Farm. The Pinney PAC site was disced under. Cover crops are planned for the area beginning in March 2023.

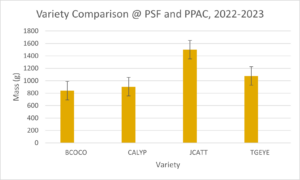

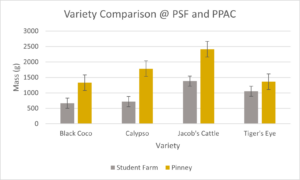

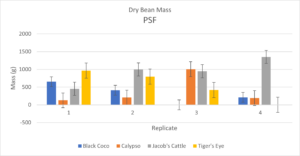

Preliminary Results

Dry beans were weighed by replicate in grams after threshing and winnowing was complete. Preliminary results for 2022 and 2023 are shown below. Variances were not pooled across sites. Unfortunately, in 2023, the field site at Pinney was lost due to overwhelming weed pressure, so only the PSF field site was harvested in 2023.

Figure 7. Comparison of average mass (g) produced by each variety in each replicate at PSF (gray) and PPAC (gold) in 2022.

Figure 7. Comparison of average mass (g) produced by each variety in each replicate at PSF (gray) and PPAC (gold) in 2022.

Figure 8. Comparison of individual replicates of varieties at the Purdue Student Farm in 2023.

Figure 8. Comparison of individual replicates of varieties at the Purdue Student Farm in 2023.

Figure 9. Preliminary analysis of variety performance pooled across both field sites in both years.

These data combined with anecdotal experience in the field can yield some insight for grower recommendations. In 2022, one of the major differences in performance between the two field sites was the performance of Calypso. Calypso performed poorly at the Purdue Student Farm and performed much better at Pinney in 2022. This may signal a strong response to well-drained soil conditions at Pinney versus poorly drained conditions and weed pressure at the Purdue Student Farm. The data show that, generally, Jacob’s Cattle is the best performer across both field sites. All other varieties performed similarly to each other.

2022 Deliverables

In 2022, the dry edible bean trial was involved in the following:

- Featured as a field stop at the Pinney Purdue Vegetable Field Day on 8/9/2022

- Utilized as a teaching opportunity in the lab section of the Small Farms Experience course (SFS 210), taking place at the Purdue Student Farm, in September 2022

- Purdue Vegetable Season Pass (community supported agriculture) participants (86 families) received about 1 pound of dry edible beans in their final share for the 2022 season. Feedback on the use of the beans will be collected in the Student Farm’s annual survey of CSA participants.

2023 Deliverables

In 2023, the dry edible bean trial was involved in the following:

- Results of the 2022 project were featured in the “Dry Beans – A Large Grain for the Small Farm?” presentation at the Indiana Small Farm Conference, 3/2/2023

- Featured as a field stop at the Small Farm Education Field Day on 7/27/23

- Utilized as a teaching opportunity in the lab section of the Small Farms Experience course (SFS 210), taking place at the Purdue Student Farm, in September 2023. Students learned to use the Swanson threshing unit.

Future Plans

This trial will be repeated at both PSF and Pinney PAC in 2023. This will be the second and final year of the project, yielding 2 site years of data for analysis.

Future deliverables include, but are not limited to, the following:

- “Dry edible beans for the small scale producer” factsheet

- “Calibrating and using a push seeder to side dress crops on the small farm” extension publication

- Equipment demonstration videos

- BCS power harrow

- BCS flail mower

- Swanson plot thresher

- Manual threshing and winnowing of dry beans

Acknowledgements

First, I want to thank NC-SARE for providing the funding needed to conduct this variety trial and allow for exploration of a crop not traditionally grown in Indiana.

Secondly, I want to think Dr. Liz Maynard, Clinical Engagement Professor of Horticulture, for her advice and collaboration. Her experience growing dry beans during her graduate studies and her willingness to share in the labor needs of this project were indispensable.

Others I would like to thank include the Purdue Student Farm, including Chris Adair, Farm Manager, and Joe Tilstra and Alfonso Rosselli, former student production interns, for their assistance in installing and maintaining this project. Alfonso assisted in planting and installing irrigation at both field sites in 2022, as well as field maintenance. Joe assisted in planting at PSF in 2023. Chris and his farm crew made sure that the crop was protected from wildlife using a deer fence and helped weed and schedule irrigation for the beds in 2022. In 2023, the entire farm was enclosed by a deer fence so wildlife predation was less of an issue. I would also like to thank Dr. Petrus Langenhoven, Horticulture and Hydroponics Crops Specialist at Purdue, for his advice and the use of his field equipment during the growing season.

Lastly, I would like to thank Dr. Steve Hallett, Professor of Horticulture, for inviting me to teach his Small Farms Experience course about dry edible beans and variety trials, and instruct students during lab time about harvesting, threshing, and winnowing dry beans in 2022.

What follows is several more photos from the project and its deliverables.

Figure 14. Variation in appearance of Tiger’s Eye bean from several individual plants and pods from the 2022 season.

Figure 16. Testing the irrigation setup at planting at PPAC, 6/13/23.

Figure 16. Testing the irrigation setup at planting at PPAC, 6/13/23.

Figure 17. Aerial view of dry edible bean trial at PPAC showing weed pressure and spotty emergence, 7/10/23.

Figure 17. Aerial view of dry edible bean trial at PPAC showing weed pressure and spotty emergence, 7/10/23.

Figure 18. Rains late in the growing season resulted in a flush of weeds as the canopy was dying back in the dry beans at PSF, 8/11/23.

Figure 18. Rains late in the growing season resulted in a flush of weeds as the canopy was dying back in the dry beans at PSF, 8/11/23.

Figure 19. The Swanson threshing unit was towed to PSF in 2023 to thresh the trial’s beans immediately after harvest. In 2022, plants dried down for about a month before threshing operations could be completed, resulting in beans dry enough to shatter.

Hosted a Cover Crop Field Day with Extension Educators, Ag Professionals, and business folks in March 2023 with 37 attending.

24 Indiana Conservation Partnership ag professionals trained at the Pollinator Field Day August 2023, pollinator health can improve pollination of various crops.

2 Permaculture workshops in Northwest Indiana (December 2022 and November 2023_ with 50 ag professionals and farmer leaders learning various concepts, including a Black Walnut workshop on harvesting and using the nuts. Many people are interested in agroforestry and using trees in their diversified farms.

2023 A Purdue Extension educator/specialist attended the Organic Field Day for training.

Organic Small Grains Field Day Feb 2023 had 56 ag professionals and farmer leaders attend.

Mini-grant to OFARM professional development and strategic planning for 11 ag professionals and farmer leaders.

Small Farm Field Day July 2023 Purdue University 189 ag professionals and farmers trained on hands-on demonstrations.

2023 Travel scholarship for an ANR Extension Educator to get training on drone thermography to share with other educators.

Jan 2024 Travel scholarship for an Extension Educator to attend the Organiz Grain conference in Sandusky Ohio, with Ohio State University. the educator shared this write up:

Ohio Organic Grains Conference grows community

The Ohio Organic Grains Conference was held January 4th and 5th at Maumee Bay Lodge and Conference Center in Oregon, OH. The Conference brought together farmers, ag professionals, and a wide variety of vendors under one roof for two days of learning and networking.

I learned about several topics, including Canada thistle management techniques and ideas, the use of extended crop rotations to mimic nature, using moldboard plows for shallow tillage rather than full inversion of the soil profile, and manure management from different species origin. I was able to network with several vendors and professionals who will hopefully add to Indiana organic extension programming in the future. I have already seen a benefit to my extension programs: 1) sponsorship interest for the Indiana Organic Grain Farmer Meeting from two vendors I connected with at the OH Conference, and 2) connections with potential speakers for future events here in Indiana.

January - March 2024, Ashley Adair, an Organic Extension Specialist and many other specialists worked on a course to teach 15 Extension Educators and other ag professionals about Organic Ag

- Jan. 16, 2024 - Modules 1 Introduction & 2 NOP Regulations

- Jan. 30, 2024 - Modules 3 Soil Health and Fertility & 4 Crop Rotation

- Feb. 20, 2024 - Modules 5 Tillage, 6 Weed Control, & 7 Pest and Disease

- Mar. 5, 2024 - Modules 8 Certification and Record Keeping & 9 Harvest and Storage

- Mar. 19, 2024 - Modules 10 Transition & 11 Profitability and Marketing

- Apr. 2, 2024 - Module 12 The Role of an Advisor

Feb 2024 Conservation Tillage and Tech Conference sent two Extension Educators to Ada, OH. One attendee, "I attended several of the breakout sessions on reduced tillage and cover crops. I used the resources I learned there to incorporate into several of my presentations in Indiana this past year. " the other shared,"...that was the first time I attended that conference in recent years. The most impactful session was given by Patrick Bailey, ODA-DLEP Engineer, on “Calculating Nutrient Application Rates,” which was on the Nutrient Management track of the conference. I shared his information with Extension Educators in our Area 11 ANR to put together a “Nutrient Management” workshop, which was held on November 7th at the Allen County Extension office. Agenda items were the 4Rs, manure and soil analysis, and nutrient management plans. The final session of the day was where different scenarios were given. Everyone used a copy of the Tri-State Fertilizer Recommendations to calculate how much manure is needed. I also attended many no-till, cover crops, and soil health tracks. Jim Hoorman is a former OSU Extension Educator and NRCS Soil Specialist who presented many sessions such as “Using Crimper Crop Rollers” and “Cover Crop Nutrient Uptake and Value.” I ended up having Jim come to both a morning and evening Field Day on August 21st as the featured speaker. His education helped draw in 56 attendees in the morning and 45 for the evening program focusing on soil health. As a follow-up, many asked if he could return and go into greater detail for another workshop. I recently had him return for an “All Things Covered” winter meeting on December 11th, with 31 producers in attendance. Jim discussed soil sampling and what values should be placed on certain nutrients. I got to work with Dave Lefforge, ISDA soil scientist, most of the time at the CCSI booth at the Conservation Tillage and Technology Conference in Ada, Ohio. It was good to learn from him and replicate a variety of soil demonstrations for participants. It is always good to see Purdue Extension specialists, such as Dan Quinn, speak, which is good information for the Purdue On The Farm program.

March 2024 Howard and Tipton County Cover Crop Field Day Tipton, IN 9 ag professionals and farmer leaders on Fertilizer rates, biologicals, soil health demonstrated,n and strip-till discussion panel.

May 2024, Natural Resources Training for 22 Extension Educators to learn about prescribed fire, educational programs to teach our communities, communicating with woodland owners with field tours of oak wilt management, harvesting timber and stand improvement, tree planting demonstrations, and facilitated discussion to learn the needs of Educator's communities. One educator shared they learned this, "Encourage landowners to create management plans for their property. Assisting landowners in

connecting with a consultant forester using resources provided. As a new educator with an HHS

background, I find this information beneficial for providing information and education to my heavily focused FNR community."

4 travel scholarships to grazing schools in two places in the state (north and south) for Extension Educators to learn about forages. August 2 and 3, 2024, in the Loogootee area (south), and September 27 and 28, 2024, in the LaGrange area (north). One Educator reported, "I learned a lot about the technology that assists with rotational grazing, and I feel like that is the biggest barrier to entry for people just getting into pasture management. It was also nice to have the hands-on experience of going out into a field managed for grazing/hay, identifying forages, and having a visual. The location I was at had what I would consider to be a smaller pasture for the amount of cattle on it but was significantly more productive than my pastures back home."

The programs run from 1-6 p.m. Friday and 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Saturday. Attendees heard from featured speakers and host Keith Johnson, Purdue professor of agronomy and Extension forage specialist; Jason Tower, Southern Indiana Purdue Agricultural Center superintendent; Ron Lemenager, professor of animal sciences and Extension beef specialist; Jackie Boerman, associate professor of animal sciences and Extension dairy specialist; Grant Burcham, DVM, veterinary diagnostician; and many other experts.

“Attending a grazing school can be a transformative experience. Attendees can take the education learned and implement the practices on their farm. The networking among instructors and attendees is also apparent at a grazing school,” Johnson said. “This interaction has value as future questions can be directed to instructors and other producers that were part of the event.”

Training will consist of field tours and pasture walks. There also will be small-group discussions with featured experts and other school participants.

August 21, 2024, 112 people attended the Western Lake Erie Basin Regenerative Agriculture Tour - Hosted by the Western Lake Erie Basin Advisory Group, this tour lets you see effective farming techniques that enhance soil health, protect water quality, and produce high-quality, nutrient-dense food. Join us for an immersive field tour in the Upper Maumee watershed as you firsthand explore the impact of sustainable farming practices on vegetable, grain, and livestock production. Learn directly from farmers successfully implementing these practices and from renowned soil health expert Ray Archuleta. Engage with innovative farmers, conservation organizations, and state agencies who are revolutionizing agriculture in the Western Lake Erie Basin watershed. This was a collaboration with Ohio and Michigan for our ag professionals and farmer leaders.

September 2024 Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Field Day Write up by Ashley Adair

Indiana SARE supported the Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Field Day (MMWCFD), held at Purdue University for the first time in the event’s history, on September 11th, 2024. The event attracted 267 total participants from across the Midwest and Canada. Purdue University partnered with The Land Connection, an ag service non-profit based out of Champaign, IL, and Glacial Drift Enterprises based out of Minneapolis, MN to plan and host the event. The planning team consisted of Purdue Extension professionals, Purdue Ag Center farm managers, a representative from a local cover crop and forages seed company (Byron Seeds), and two Indiana farmers, one representing large scale organic row crops and another representing small-scale diversified vegetable production.

The MMWCFD is a one-day event that features educational presentations in the morning followed by equipment demonstrations in the afternoon. The event has traveled to private farms and land-grant universities across the Midwest, including Michigan State University, Ohio State University, PrairiErth Farm in Clinton, IL, and beyond.

There is a trade show that takes place from the event kickoff until just after lunch where equipment dealers, ag service providers, university researchers, and others can meet with event-goers and make connections.

This year, the planning team decided to present educational sessions as additional in-field demonstrations rather than static presentations. Josue Cerritos from Dr. Steve Meyers’ horticulture weed science lab presented a talk on silage tarping as a method of no-till weed control during the morning education sessions this year.

The other morning education sessions focused more on high-tillage methods of weed control, including a demonstration of two different styles of moldboard plows (a 7-bottom reversible plow and a 2-bottom plow with cultimulcher). For organic farmers, shallow moldboarding (5 inches or so) is a viable method of soil aeration and burial of weed seed, and is acceptable when used sparingly and when incorporating plant residue, such as from cover crops.

After the morning education sessions concluded, a networking luncheon with table discussion topics was available for folks to convene over mutual interests. Topics included Canada Thistle Support Group, Hand Tools and Horsepower – Weed Control Without Motors, Low-Till Weed Control Strategies, Moldboard Plow Strategies, Tips for the Toolshed During Organic Transition, and Using Cover Crops for Weed Management.

The MWCFD’s “main event” is its afternoon in-field demonstrations. A wide variety of weed control equipment from diverse manufacturers is displayed and operated so that participants can better understand how the equipment operates under field conditions. Equipment dealers explain setup, calibration, and operation to participants.

Participants indicated the following in the event evaluation:

- That they were very likely to or will absolutely change the way they implement a practice on their farm or land (78%)

- That they were very likely to or will absolutely do further research about a tool or strategy seen at the field day (95%)

- That they were very likely to or will absolutely follow up with a participant I met at the field day for advice about my farm (85%)

- That they learned something new (95%)

- That they expanded their network of farmers and industry professionals (84%)

- That they were encouraged to re-examine plans for the upcoming farming season (73%)

Out of 97 submitted evaluations, the following describes the community in attendance:

- Certified organic (49%)

- Transitioning to organic (21%)

- Conventional (21%)

- Non-farming (23%)

IN-SARE supported the attendance of one Purdue Urban Agriculture Extension Educator to this event. They shared: "

NCR-SARE award ONC24-141 funds helped to support the animal traction demonstration by the Bilenky Sustainable Horticulture Lab at the field day this year. Dr. Bilenky demonstrated animal-powered implements for weed control, including a field cultivator as well as a custom-built harrow with a rolling basket. This type of demonstration was a new addition to the MMWCFD in 2024 and provided participants unfamiliar with animal traction a new perspective on how weed control and other activities might be undertaken on a small- to medium-sized farm.

This event took about 9 months of planning. In addition to the planning team, all hands were on deck for the field day itself, with additional extension professionals (Tricia Herr, ANR Montgomery County; Amy Thompson, Beginning Farmer Coordinator) on-hand to direct parking and traffic flow. Additional Purdue staff, such as Purdue Entomology’s Laura Ingwell and Purdue Diversified Farming and Food Systems’ Nathan Shoaf, participated in the trade show with a black soldier fly demonstration and resource sharing, respectively.

Following are some images from planning meetings earlier in 2024.

The Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Field Day was made possible by the following individuals:

Planning Team

- Ashley Adair, Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture

- Sam Oschwald-Tilton, Glacial Drift Enterprises

- Crystal Siltman, The Land Connection

- Jay Young, Throckmorton Purdue Ag Center

- Chloe Henscheid, Meigs Horticulture Research Facility

- Sarah Brackney, Purdue Extension – Daviess County

- Steve Meyers, Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture

- Moriah Bilenky, Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture

- Aaron Fisher, Byron Seeds

- Jason Federer, Living Prairie Equipment

- Daniel Garcia, Garcia’s Gardens

Volunteers

- Purdue Ag Centers director Jon Leuck, superintendents, and staff (who donated their time and volunteered people-movers for the event)

- The Meyers Horticulture Weed Science Lab

Special thanks to NEPAC superintendent Chris Lake and technician Carl Emley for their assistance during equipment load-in, load-out, and setup.

The Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Day was a wonderful opportunity to get hands on learning around the tools used for weed control and the current technology around organic/mechanical weed control. I was able to watch equipment that is specifically geared towards the smaller scale, urban ag settings that I serve as well as options for the home gardener/homesteading community. The trade show was a fantastic place to speak to the professionals who are intimately acquainted with the capabilities of the tools and product they represent. I am working on creating a tool library out of my office for clients to be able to use and this was the perfect opportunity to see what would best serve them." with these three photos shared:

September 27, 2024 FAMANCHA training for goats parasite management for Extension Educators.

Dec 10-12, 2024 Great Lakes Expo, Grand Rapids, MI, 2 Extension Educators attended with travel scholarships - The Great Lakes Fruit Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO is the PREMIER show to Connect Innovate and Grow. You will connect with over 4,500 fruit, vegetable, farm market and greenhouse individuals and over 400 industry-leading companies. You will learn how to implement the newest innovations on your farm. You will grow your thinking and your business by applying new techniques and knowledge to problems that are limiting your potential. From one attendee: "The experience was undoubtedly worth my time. Beyond being simply enjoyable, it was an opportunity to deepen my understanding of the products and services available to specialty crop growers. Informative trade show vendors demonstrated the utility of innovative irrigation systems, cultivation and harvest equipment, as well as packaging and processing materials and machines. Along with my travel colleague, Amanda Bradshaw-Burks, we were able to connect with a mushroom growing company that is interested in sending us sawdust spawn for experimentation in Callery pear logs. The sessions I attended included information on cucurbit disease, nutrient management, online diagnostic and treatment tools, and the Final Water Rule for water safety on and around specialty crop farms. The GLE also had opportunities to browse an indoor farmer’s market, where I was able to chat with small business owners about the realities, struggles, and positive experiences they had starting their businesses. Small, simple interactions like this, even if it isn’t with my own clients, help me to better understand the current market environment and what kinds of support these producers need to be and remain successful. Beyond the learning value of the Expo, I found great worth in networking, not only with those from Purdue who also attended, but with Michigan State Extension personnel. It is only recently that I have returned from the professional development trip, so I have yet to share all that I learned. My primary interest moving forward in my new work position will be to share information about the Final Water Rule (EPA) and nutrient management decisions in specialty crops. Thank you for the travel scholarship, it was put to good professional use." From the second participant: "The Great Lakes Food Expo

was absolutely fantastic. Sessions I attended included information on: Disease management in the greenhouse, season extending for flower production, tomato – pepper – eggplant, mushroom cultivation as well as commercial wild harvesting, farm planning for organic farmers, farm market layout and design. All of these sessions were fantastic in the areas they taught in and gave me a lot of information to bring back to the clients I serve. Another aspect of the expo was the extensive trade show. The number of organizations and products represented was overwhelming but I was able to see it in it’s entirety over the course of the week. I was able to get a BUNCH of resources to bring back to Indiana; everything from information on maintaining water quality, to invasives control, to season extension, to bio control of pest, to fruit production, commercial products available, and more. I was also able to chat with a myriad of folks leading amazing initiatives that are a model for what I would love to see in Southern Indiana. We were able to connect to a number of other Extension folks and different agencies and chat about what they are doing in their respective states. This included bringing back informational display material that will be an asset to the clients I serve. Notably, I was given a hive of live Eastern Bumblebees to bring back by one of the vendors who used it for display at the trade show! It was a fantastic teaching aid while they were survived."

Indiana remains a leader in soil health practices and cover crop adoption. The various levels of knowledge across the state require a tiered training program for professionals and specialized training for specific production models

Each program focuses on the environmental and economic sustainability of soil health practices while touching on the social aspects of these practices.

- 15 ag professionals and specialists visited an Intensive on-farm workshop no-till farm in Portland Maine where they learned no-till intensive urban. One participant wrote, "It was truly an invaluable learning opportunity for me in which a lot of gaps in knowledge were filled on how to successfully implement soil health and ecological principles on a small farm. I will undoubtedly use this knowledge going forward in my work with urban and small-scale farmers across the state. Equally important, I was able to authentically connect with Purdue staff who are working towards the same goal of providing sound and applicable information to our community of growers in Indiana. We identified multiple ways in which we can work together."

This training in Maine was a core professional development topic in an Urban Soil Health Update meeting (with nearly 50 ag professionals attending) and a "Get the Dirt" Urban Soil Conference in September, where approximately 100 ag professionals and farmers heard Daniel Mays and interacted on Zoom.

This training in Maine was a core professional development topic in an Urban Soil Health Update meeting (with nearly 50 ag professionals attending) and a "Get the Dirt" Urban Soil Conference in September, where approximately 100 ag professionals and farmers heard Daniel Mays and interacted on Zoom. - Intro to Soil Health Workshops - Fundamentals of Soil Health Training April - June 2023 had 38 ag professionals trained. Participant shared,"Our county's annual PARP (Dec 2023) highlighted soil health, and was really well received! I implemented some of the training I'd received through SARE-related events, so thank you!"

- Soil Health and Sustainability for Midwestern Field Staff - 8 people trained in this hands-on workshop. Also the Soil Health Signature Program train the trainer, trained 15 Ag Extension Educators in December 2023

- NWF Grow More Training (Conservation Communication) 4 trainings across the state with 61 ANR Extension Educators and other ag professionals trained. One participant wrote," Grow More training was very insightful, would love to see programs like that. "

- 3 ANR Extension Educators attended a grazing conference in Winchester, IN where they learned about soil health practices in grazing.

- 90 Soil Water Conservation Indiana staff trained in webinars throughout the summer months on professional development.

- 90 Soil Water conservation Staff attended the annual Fall Professional Development training. SARE had a grant talk and some grants were written because of that training.

- NRCS beginner training in soil health November 2023 Ft. Wayne with 52 NRCS personnel

- Natural Resource Forestry Training to Extension Educators - 21 educators were trained.

- Urban Ag Field Day training July 2023 Ft Wayne, Ag professionals and farmers trained with Urban Soil Health Program.

- April 2024 Fundamentals of Soil Health -35 ag professionals attended this program that was Tuesdays in April Apr 2,16,23=Virtual; Apr 9=In-person. This train-the-trainer event provides a foundation for understanding how cover crops and no-till systems may be incorporated into Midwestern cropping management and impacts on soil health.

- June 2024 Soil Health and Sustainability Training for Midwestern Field Staff AKA "3 day" is an annual train-the-trainer event teaching consistent soil health messaging to Indiana Conservation Partnership staff. More than 40 participants from around the state attended.

-

Day 2 at West Lafayette with Soil Health and Sustainability Training for Midwestern Feidl Staff AKA "3 day" - August 2024, 39 attendees (with representatives from most of the Indiana Conservation Partnership) is a new program Ag 101, working with CCSI, Purdue on the Farm (Purdue Extension and other partners) to share with ag professionals in Indiana, including Farm Service Agency with feedback like this, "I wanted to let you know the Ag 101 training was great! They had excellent speakers, examples, and field exercises. Thank you for the opportunity! I hope more PA’s will be able to attend." SARE has worked with our partners, helping to recognize the need for ag professionals who don't have the chance to grow up on a farm to get back to basics to be able and more comfortable to talk with the farmers we want to help every day. This was capped at 40 people to make it hands-on, and many people wanted to attend with a waiting list.

Ag 101: Commodity Crop Production Training was held in West Lafayette last month. The training included plant ID and growth staging, discussion about when farmers do what, farm equipment, plot walks and more. Here is some feedback from participants. You can see why we plan to hold more of these sessions in 2025! Thank you to our expert instructors and to all of the conservation partners who were able to attend!

Some attendee comments:

· I feel more equipped to walk into a field with a local farmer and support them as needed.

· This training helped me to better understand the intensity of the decision making that farmers experience daily and on a year-round basis.

· This course helped me to acquire basic foundational skills and knowledge to support farmers, allowing me to feel more confident in agricultural processes in general.

· It was great to meet with our Indiana Conservation Partners to strengthen our relationships and learn more about what our commodity crop growers go through in the year.

· The growth stages with the plants were really useful to see and touch to understand what I have seen in a book for a while.

Adam Shanks is reviewing farm machinery with the Ag 101: Commodity Crop Training group.

Learning about plant growth staging at Ag 101: Commodity Crop Production. 40 attendees are here from across the Indiana Conservation Partnership.

Indiana Conservation Partnership includes all of these organizations working together August 2024 - ICP Pollinator Habitat Management Field Day This field day covered pollinator habitat

establishment and management practices such as drilling vs. frost seeding and seasonality of

prescribed fire. 23 Attendees visited several field demonstration sites and discussed the results of

various establishment and management practices. Participants were provided with handouts and

additional resources.October 2024: Get the Dirt Conference with a travel scholarship for one Extension Specialist and travel for speakers to train ag professionals.

This annual full-day event is for conservation and agricultural professionals working

with urban and small farms, vegetable growers, and diversified farms. In 2024, 80 people joined each year to learn about the landscape of IN growers, microbiology,

perennial plantings, beneficial insects, regenerative homesteading, and fully integrating

conservation practices on farms.October - Maine No-Till Trip 8 travel scholarships for ag professionals and a couple of farmer leaders/ag professional combos

-

-

Thank you all so much for including me on the trip to Maine I had the absolute best time and learned so much that I can’t wait to implement on my own farm. It was a breath of fresh air to see both farms and our group was so much fun and I think we will all stay in contact after that.... [then later]...Maine was a total game changer and I can’t wait to get everything implemented, my husband is even sold on everything and he worked out there all last weekend to help me make the transition to permanent raised beds!" - Bree Ollier, Hendricks County SWCD and grower at Copper Cataract Homestead. Bree has hosted NRCS and the public at her farm for field days and demos, so will continue to spread the take-aways to conservationists and growers.

-

"What an amazing trip. The comradery, networking, and perspectives within our group of conservationists, growers, and small farm advocates were as beautifully productive as the farms that graciously hosted us. A special thanks to SARE, Urban Soil Health, Frith Farm, and Stonecipher Farm. Daniel May's wisdom, Ian Jerolmack's keen business sense, and their dedication to soil health and intensive production made for highly educational and enlightening farm tours." - Kevin Allison, Marion County SWCD

Photo taken by Kevin Allison showing growing veg between high tunnels

Photo taken by Kevin Allison showing deep mulch method with rich soil beneath "I came back from this trip feeling confident to advise any vegetable producer in soil health practices after seeing two different successful farms and their management strategies. Compost was so integral in their success that I will be suggesting it to all my clients. I was also energized to continue my efforts in cultivating high quality food. Thank you so much for this opportunity." - Elyssa Lewis, Allen County SWCD

"I came home with a notebook full of practical and successful ideas to share with other producers and to try in my own vegetable beds! This workshop was intense but oh so worth the time! The tips and tricks that make a soil system healthy make so much sense now after walking through plots and houses where those practices are being used to improve productivity and creating healthier soil to ensure sustainability. Thank you so much for this opportunity and to everyone who made this trip possible. The information gained will be invaluable!" - Lisa MacPhee, Morgan County SWCD

"I had the opportunity to visit two very well run farms this past weekend, Frith Farm and Stonecipher Farm in the Portland, Maine area. There were 8 of us from around Indiana that attended. A special thanks to Megan with Urban Soil Health for setting this trip up." - Ryan Lee, Lees Edible Acres. Also on the St. Joe County SWCD board, and an active member in their local Urban Soil Health Working group SCRAP.

https://www.stjosephswcd.org/urban-ag-and-conservationhttps://www.facebook.com/share/p/19q2E4Vjmq/

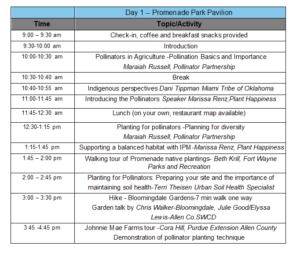

November 18-19, 2024 Pollinator Urban Workshop Professional development for 14 ag professionals and farmer leaders, here was the agenda for both days:

Pollinator Steward Certification Workshop

for Urban Farmers and Gardeners

Project Wingspan: Monarch Butterfly Pollinator Steward Certification Program Day 1 Promenade Park Pavilion

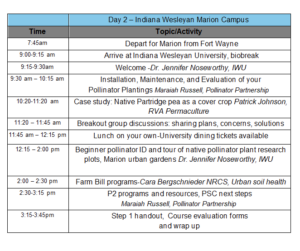

Pollinator Steward Certification Workshop

for Urban Farmers and Gardeners

Project Wingspan: Monarch Butterfly Pollinator Steward Certification Program Day 2 - Indiana Wesleyan Marion Campus

Land access is the biggest hurdle to beginning farmers nationwide. Beginning farmers in Indiana struggle to find and afford farmland in urban and rural settings (based on Marion County needs assessment).

Work on creating and Access and Land Conservation in Indiana community of practice

- Land Access and Land Conservation in Indiana – Community of Practice Kick-Off Event with 42 participants across Indiana and different fields that 'touch agriculture"

- Community of Practice Monthly Meetings (virtual) where they learn about land use and what is happening in other states. One participant writes, "The group composition is terrific because there is expertise from so many different areas. Also, the outside speakers and resources have done a nice job of presenting interesting solutions from other states." And, a planner writes, "As a planner, I'm always checking what we are discussing against my local zoning ordinance to see how it is handled. We are super ag-friendly and intend to stay that way, even on small lots. However, I can understand how folks looking to expand or get started have a very difficult way to go, especially if they are trying to make farming their full-time profession."

- 2024, The community of practice webinars with 39 participants every month joining and learning https://www.indianafarming.org/what-we-do/programs/farmland-community-of-practice met for 10 months, with new professionals sharing resources each time. https://www.indianafarming.org/what-we-do/programs/farmland-community-of-practice/recordings-resources is the link to all the meetings and resources.

- In June 2024, 14 Community of practice members met with a group to discuss action items with the Stratego process. Some curricula were created to teach the resources of land access.

There is increasing activity at the city, county, and state levels to understand and implement community food policies and programs to address disparities in equity, access, health, profitability, and community resilience to climate change. However, discussion, programming, and funding can and do take place without community capital asset mapping and the knowledge of existing food policie