Final report for ONC17-023

Project Information

Sustainable agriculture is gaining interest in cities due to its ability to reclaim polluted land, minimize food miles, mitigate food deserts, and create entrepreneurial opportunities. Yet, small margins and an over-reliance on vegetable production affect the long-term viability and resiliency of small-scale urban farms. Outdoor mushroom production is a low capital, low overhead, high margin crop, well suited to urban space constraints. Utilizing low productivity areas (flood-prone, shaded, intercropping), small-scale production can be maximized using low-cost waste stream substrates and enhancing soil health. To our knowledge, Indiana has no outdoor mushroom market producers, limiting support for farmers seeking to diversify through this market. The overall goal of the project is to foster farmer collaboration that leverages shared interest, expertise, and experience to create a model of low input diversification that maximizes profitability for small-scale urban farms. Local best practices for outdoor mushroom production in Indianapolis was explored and trialed at four sub-acre farms in Indianapolis by providing partner farmers with production expertise, start-up resources, and shared resources. This project will more broadly benefit urban farmers throughout the North Central Region by applying expertise from indoor and rural mushroom operations to test viability and profitability in small-scale urban contexts.

The project’s overall goal was to help resource-limited urban farmers trial outdoor mushroom production to diversify crops, income streams, and the local food economy. The following objectives will be pursued:

Objective 1. Reduce barriers to outdoor mushroom production through training and resources for four Indianapolis urban farmers.

Objective 2. Determine feasibility and local best practices for mushroom production in Indianapolis’ urban setting and climate.

Objective 3. Research the local market and create cohesive marketing materials for mushrooms in Indianapolis.

Objective 4. Disseminate findings to regional farmers through field days, the Indiana Small Farms Conference, and online documentation.

Overall Project Outcomes:

This project had positive outcomes for farmer partners, other regional growers, local consumers, and Indianapolis and regional urban food systems. Farmer partners forged deeper collaborations with one another while acquiring new skills, benefitted from resource sharing, and increased their farm’s economic viability through low-input product diversification. The expansion of products offered enriched, and will continue to enhance, the local food system by providing nutrients unique to non-animal products. At the end of the project, farmer partners completed a survey to understand how this funded project changed their knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Success was also measured quantitatively through measurements of yield and revenue and the development of best practices documentation.

The most impactful local outcomes of the project were twofold. First, farmers that wouldn’t normally collaborate and support one another—either because they work in isolation, are direct competitors, have differing reasons for growing, or are more experienced or less experienced than others—discovered that they benefitted from collaboration around a common goal of mushroom production. We expect these farmer partners to continue collaborating and supporting one another in the future, which may be particularly important for the more inexperienced growers and for growers without support of a larger organization such as a university or non-profit. Secondly, by establishing a clean inoculation room for independent spawn production, farmers have a physical space with which to meet and collaborate, but will also save money and diversity mushroom varieties offered in Indianapolis. More broadly impactful, this local spawn production and planned future training of mushroom production with other urban growers will bolster the local market for mushrooms in Indianapolis.

Overall the project developed best practices and reduced barriers in the North Central Region for mushroom production in small-scale urban operations, with unique resource constraints. Product diversification via mushrooms have the potential enrich local markets, provide financial stability, and enhance nutritional offerings in local communities. The impact of the project beyond the four participating farmers was showcased by outreach and education to over 2,000 people through individual farm tours, workshops, and local (Indiana Small Farms) and national (Our Farms, Our Future) conferences.

Cooperators

Research

The methods reported in this section were those included in the original proposal. Methods and materials changed as the project developed and farmer partners discovered more efficient, practical, and/or sustainable approaches to production, marketing, and education. The changed methods and materials are presented as part of the Results and Discussion section of this report.

Objective 1. Reduce barriers to outdoor mushroom production through training and resources for four Indianapolis urban farmers.

In March 2017, farmer partners will participate in a 2-day workshop, led by Mark Jones, Sharondale Mushroom Farm. Topics include fungal biology and ecology, tissue culturing, spawn production, growing methods for various mushroom species, post-harvest handling, marketing, mushroom mycelium revenue, food safety, compliance with USDA-GAPS and organic certifications, value-added products, and customer education—focusing on shiitake, oyster, and king stropharia. Mr. Jones will assist each farmer on-site to determine the ideal location(s) for mushroom production and provide site-specific guidance. Mr. Jones will serve as a project consultant throughout the project.

Objective 2. Determine feasibility and local best practices for mushroom production in Indianapolis’ urban setting and climate.

After the workshop, each farmer partner will determine the waste stream products available (wood chips, logs, sawdust, straw) and order appropriate spawn and supplies. Inoculations will occur in April 2017, with fruiting expected 6-18 months. Each farmer will report to the group: inoculation date, mushroom strain and substrate, site location, shade type, variability in temperature and relative humidity (instrumentation provided by Butler), watering dates, forcing dates (if used), fruiting date, flush yield, and sales revenue.

In year 2, farmers will conduct new inoculations, if desired, continue to monitor production, and compile best practices on: mushroom species and strains for best yields, obtaining substrates, and manipulating microclimates. Farmers will meet quarterly to discuss trial status and to create collaborative documentation for best practices, marketing, and presentations.

Objective 3. Research the local market and create cohesive marketing materials for mushrooms in Indianapolis.

From April–August 2017, farmers will explore the local market for mushrooms by polling customers and retail outlet. Farmer partners will likely sell through four existing main channels: farmers markets, farm stands, CSA programs, and retail sales.

From September 2017–February 2018, farmers will collaboratively create marketing materials for mushroom products that advertise the new local product in Indianapolis by IndyGrown partners—a network of urban market farms. Minimally, stickers and flyers will be created to promote “Grown in Indy” products and each market farm individually and will highlight the superior taste, freshness, nutritional density, and shelf life of naturally grown, local mushrooms. Materials will be distributed at local farmers markets, farm stands, retail outlets, social media, and using Purdue Extension and Indy Food Council partnerships. Each farmer will also undertake individual marketing efforts.

Objective 4. Disseminate findings to regional farmers through field days, the Indiana Small Farms Conference, and online documentation.

June 2018–August 2018, farmers will host field days for Indianapolis’ 130 growers. Best practices documentation and factsheets will be posted onto the Butler University, IndyGrown, and Purdue Extension websites by February 2019. Farmers will present outcomes to other local farmers at the Indiana Small Farms Conference in March 2019. Because all farmer partners have a mission to educate the Indianapolis community about local, sustainable foods, the benefits of mushrooms will be shared with K12 students, community gardeners, and college students through farm tours.

The materials and methods presented prior to this section in the report, may have changed based upon farmer discussion and decision-making regarding the best way to conduct the project.

Objective 1. Reduce barriers to outdoor mushroom production through training and resources for four Indianapolis urban farmers.

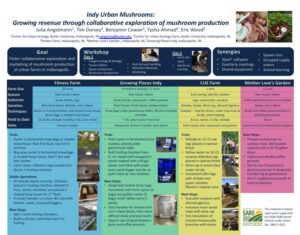

The CEO of Sharondale Mushroom Farm, Mark Jones, led a 2-day mushroom biology and production workshop hosted at Butler University in March 2017 for four farmer partners. All four farmer partners run sub-acre, highly diversified operations in urban Indianapolis. The first day of the workshop focused on fungal biology and ecology, tissue culturing, spawn production, growing methods for various mushroom species, post-harvest handling, marketing, mushroom mycelium revenue, food safety, compliance with USDA-GAPS and organic certifications, value-added products, and customer education—focusing on shiitake, oyster, and king stropharia. The second day of the workshop was devoted to site visits to each farm to assess the unique benefits and constraints for on-farm locations for mushroom production as well as farmer access to waste stream products for mushroom substrate. After site visits, farmer partners learned how to inoculate wood chips with king stropharia sawdust spawn and inoculate Ailanthus altissimalogs (aka tree-of-heaven, a non-native invasive in Indiana) with yellow oyster sawdust spawn. Inoculated logs were divided equally amongst farmers so they could determine prime locations for log production on their farms. Inoculated wood chips were located under the partial shade of seaberry bushes on farm 2 and allowed to run for 3-4 months. Once the mycelium ran, the substrate was shared amongst all farmers so that their farm soil quality could be enhanced by king stropharia. At the end of the workshop, farmers were given the opportunity to select from a variety of spawn, log inoculation starter kits, and education materials to jump-start their production trials.

After the workshop, the mushroom farm in Virginia served as a consultant to Indianapolis farmers primarily via online communication. The farmer partners determined that the online platform Slack, which can send notifications to smart phones in real time, would be the best way to communicate, especially with limited access to email throughout the day. On this platform, farmers shared successes, challenges, and coordinated equipment and supply use with one another. For example, the farm 2 has a truck with a reinforced bed that can transport heavy substrate materials that can be used by the other farmer partners, two of which do not have access to a truck. Farm 1 quickly constructed the equipment for straw sterilization to produce inoculated mushroom bags. Use of this facility has been offered to the other three farms to minimize the need for repetition of these facilities and to help educate and minimize barriers for other farmers who wish to set up this operation. One farmer frequents the area of the consultant’s mushroom farm and has made site visits to see the operation there and to pick up mushroom spawn and supplies at reduced cost for the other farmer partners. These synergies have reduced the barrier to entry for the farmer partners by creating a community working together on site-specific mushroom production.

After the first year, engagement on the Slack channel decreased to where it was almost non-existent and farmers began communicating primarily through text and in-person meetings. This was a surprising result for the program coordinator who is not a grower because they assumed that in-person meeting would be constrained by time limitations when, in fact, digital communication especially on a platform separate from email/social media is difficult to engage with regularly. While Slack was well-used in the first year, as farmer partners grew in the confidence and knowledge of mushroom production and got operations underway, there was less need to regularly chat, ask questions, and send pictures of operations for nearly instantaneous responses. In year 2, the farmers solidified their production plans and gained confidence and knowledge in their abilities. Therefore, needed communications became less frequent and texting became an easier way for brief communications because all farmers carry phone on their person’s when in the field and it actively notifies them of a message instead of passively checking email regularly. Email became the tool of choice for preferred for sharing final documents, photographs, and dissemination materials because those items didn’t need immediate attention and could be addressed as farmers found time during the week to respond. Overall, in-person meetings were preferred for more in-depth conversations about collaboration and shared resources.

Objective 2. Determine feasibility and local best practices for mushroom production in Indianapolis’ urban setting and climate.

Given that each farmer partner has different site opportunities, access to different substrate types, and production scales of interest, it is no surprise that each farmer has selected a different approach to mushroom production. This will help strengthen the network of knowledge in Indianapolis on mushroom production over the long-term. Year 1 of the grant was focused on trailing mushroom production at four urban Indianapolis farms. 3 of the 4 farms have produced a small yield of mushrooms as part of the trial and plan to scale up in the 2018 growing season. At this time, farmers will closely track: inoculation date, mushroom strain and substrate, site location, shade type, variability in temperature and relative humidity, watering dates, forcing dates (if used), fruiting date, flush yield, and sales revenue.

In year 2, farmers conducted additional inoculations, if desired, continued to monitor production, and compiled best practices on: mushroom species and strains for best yields, obtaining substrates, and manipulating microclimates. Farmers met quarterly to discuss trial status, approaches to marketing, and create collaborative documentation for best practices and presentations. Through these quarterly meetings, the group decided to maximize sustainability of operations beyond the term of the grant award by utilizing supply funds to purchase shared equipment to build a clean room where mushroom spawn can be produced. This clean inoculation room will be housed at farm 1 and utilized by all farms to minimize future costs purchasing and paying for shipment of mushroom spawn from external suppliers. This is particularly important because a key Indiana supplier for mushroom spawn recently closed operations.

Overall, three of the four farms had success in at least a small crop of mushrooms. Farm 1 produced approximately 100 pounds of shiitake (logs and sawdust in natural wood line, blocks in indoor fruiting chambers), oyster (straw in a shed), and lion’s mane (logs in natural wood line) over two years using a variety of methods. This farm tried a variety of approaches to determine what methods work best for their farm ($500 in sales). Farm 2 produced about 25 pounds of shiitake and oysters on logs placed in an adjacent riparian forest, with intentionality about not force fruiting and working within the natural rhythms of nature ($300 in sales). Farm 3 grew about 20 lbs of oyster mushrooms in buckets of straw under greenhouse tables ($100 in sales and $300 in workshop registrations). This farm could have produced more, but experienced a personal change in year 2, which slowed production. Farm 4 was a beginning farmer with limited resources therefore, it took time to gather all the infrastructure needed to begin production. This farm successfully inoculated straw with multiple varieties of oyster mushrooms in straw and coffee grounds under a converted hoop house and has had success producing approximately a pound of mushrooms ($0 in sales). It should be noted that mycelial runs after mushroom inoculation can take from 6-18 months before fruit on logs and establishing instrumentation to sterilize other substrates took some time for the farmers to work out the kinks. These results confirm that, while a large amount of product wasn’t produced during the grant, each farmer is now established and has had some success growing mushrooms. We expect that production will only increase after the grant award ends.

See “Success Stories” under “Project Outcomes” for specifics on each farm’s production trials.

Objective 3. Research the local market and create cohesive marketing materials for mushrooms in Indianapolis.

From April–August 2017, farmers explored the local market for mushrooms by polling customers and retail outlets. Farmer partners primarily sold through three existing main channels: farmers markets, farm stands, and CSA programs. Retail sales were not a part of the sales portfolio because of the small volume of mushrooms produced. As farms scale up operations, retail sales will be an additional outlet for product.

From August 2018–February 2019, farmers collaboratively discussed the need for marketing materials that advertise the new local mushroom product in Indianapolis. Originally, it was proposed that funds would be used to produce stickers and flyers promoting “Grown in Indy” mushroom products as well as flyers and stickers for each market farm that highlight the superior taste, freshness, nutritional density, and shelf life of naturally grown, local mushrooms. Farmer partners collectively agreed that they were already successfully undertaking individual marketing efforts for their mushrooms and decided to utilize the marketing funds to construct a shared clean inoculation room with equipment that would better establish longevity and efficiency of operations by allowing farmers to produce their own spawn instead of ordering it from third-party companies with a high cost of shipping. This is particularly important given that a primary spawn producing operation in Indiana recently closed for business. This not only provides cost savings for each farmer, but may also be an additional source of revenue in the future by selling spawn to other farmers. Further, it enables the farms to identify and cultivate mushrooms unique to the climate and limitations of urban farm spaces in Indianapolis.

Objective 4. Disseminate findings to regional farmers through field days, the Indiana Small Farms Conference, and online documentation.

The results from this objective are included in the subsequent Education & Outreach Activities section of the report.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Participation Summary: Indiana Small Farms Conference (500), Our Farms Our Future Conference (900), Mushroom Cultivation Workshop (7), Farmer Partner Farm Tours, all farms (750).

In February 2018, farmer partners met to discuss the coordination of a field day/field days to showcase mushroom production best practices. Farmers decided to capitalize on an existing urban farm tour organized by the Purdue Extension Service in which they all participate each fall: the Harvest Ride. The farmers worked with the event planners to ensure that the marketing reflects this new project for the fall 2018 tour. Each individual farm planned to include their mushroom efforts as they hosted tour groups on that day. Unfortunately, the Harvest Ride for 2018 was cancelled.

To meet the educational commitment of the grant funding, starting in June 2018, three of the four farms hosted farm tours in which mushroom production was showcased, totaling more than 20 tours. These tours were to a variety of stakeholder groups including other growers, Purdue Extension Master Gardeners, K-12 students, Future Farmers of America Career Success tours, college students, and Indianapolis residents interested in mushroom cultivation. Farm 3 found a market for mushroom workshops where residents pay a fee to learn the basics of at-home mushroom production. They held one workshop with Osmos Permaculture that had seven participants who paid $45 for the workshop, which more than covered the cost of workshop supplies (one bale of straw and spawn; 5-gallon buckets donated). The workshop was three hours long with a sit-down discussion and deep dive in to mushrooms and the biology of them, how they grow, what they eat, etc. After this crash course in mushroom biology and ecology, a hands-on experience was led by the farm, drilling holes in buckets, filling buckets with fermented straw, and inoculating the straw as they were filled. Each participant left with a 5-gallon bucket of straw inoculated with oyster mushrooms. The workshop ended with a Q&A session,

Showcasing mushroom production in tours, consultations, and/or workshops will continue into future years. The farmer partners also presented at the Indiana Small Farms Conference and the Our Farms, Our Future Conference in St. Louis (posters enclosed in report). In spring/summer 2018, farmers also began documenting best practices and creating factsheets (Log Production Fact Sheet Block Production Fact Sheet Fermented Straw Bag Production Fact Sheet, Pasteurized Straw Bucket Fact Sheet), formatted the same to showcase a cohesive effort generously funded by NCR-SARE. The project coordinator presented the project at the Our Farms Our Future conference in April 2018 and the farmer partners presented a poster at the 2019 Indiana Small Farms Conference.

Learning Outcomes

All four farmer partners completed all items on a survey provided at the end of the project. The first question on the survey is below followed by additional questions in subsequent bullets:

Why were you interested in mushroom production on your farm?

All farms reported additional revenue as the key reason why they wanted to learn mushroom production skills. Two of the four farms reported greater soil health and biodiversity as another key driver. One farm mentioned maximizing unused space (wooded area), one farm reported medicinal properties of mushrooms, one farm reported diversified caloric input on the farm, and one farm wanted skills to provide neighborhood youth and junior farmers a tool that they could use for entrepreneurship in the future.Perceptions of mushroom production BEFORE participating in the Mushroom Production Project:

Farmers were asked to rank their understanding and knowledge on how to grow mushrooms BEFORE the project (Likert Scale: 1 = None, 2 = small amount/novice, 3 = decent amount/intermediate, 4 = high amount/senior, 5 = expert/professional). On average, they reported a score of 1.75 which fell closer to small amount/novice. Only one farmer reported no understanding and knowledge. Farmers were also asked to rank their confidence in cultivating and growing mushrooms BEFORE the project on the same Likert scale. Farmers reported an average score of 1.5. This score falls right in between no confidence and small amount/novice levels of confidence, with half of the farmers reporting no confidence and half reporting a small amount of confidence.

Perceptions of mushroom production AFTER participating in the Mushroom Production Project:

Farmers were asked to rank their understanding and knowledge on how to grow mushrooms AFTER the project (Likert Scale: 1 = None, 2 = small amount/novice, 3 = decent amount/intermediate, 4 = high amount/senior, 5 = expert/professional). Farmers reported an average of 4.0 on the scale representing a high amount/senior level of knowledge. Individual responses spanned from intermediate to expert levels of knowledge. Only one farmer reported no understanding and knowledge. Farmers were also asked to rank their confidence in cultivating and growing mushrooms AFTER the project on the same Likert scale. Farmers reported an average of 3.5 on this scale, which is between decent amount/intermediate and high amount/senior, with half of farmers reporting intermediate confidence and half reporting high amount of confidence post-project.

Farmers were then asked to rank three statements to understand their perception of mushroom production and farmer collaboration AFTER the project (Likert Scale: 1= strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree). The first statement was “I find growing mushrooms to be a viable economic opportunity for my farm” The score was an average of 3.0 suggesting farmers were neutral on the statement. When looking at individual responses, however, only one farmer reported 3 (neutral). On the other hand, one farmer responded 1 (strongly disagree) and two farmers responded 4 (agree). The second statement was “Mushroom production is a skill I can easily implement on my farm”, which had an average response of 3.5, half way between neutral and agree. When looking at individual responses, each farmer selected a different score spanning 2, 3, 4, and 5. These results suggest that the experience of growing mushrooms was highly variable to each farmer.

The last statement was “My farm operations can benefit from collaborative learning from other small-scale diversified farmers in my city”, with an average response of 4.25 (one farm = 3 neutral, one farm = 4 agree, and two farms = 5 strongly agree). However, we also asked an open-ended question on how farmers benefitted, if at all, from collaborative learning and all farmers reported that networking and collaboration is a huge benefit and advantage to their operation because they can learn together from individual successes and failures, bounce ideas off one another, and collectively purchase equipment. Below is one of the responses:

“We benefitted from the shared knowledge of success and failures of others. Each farm initially took on a different aspect of growing mushrooms so we could maximize our shared learning. Additionally, our pooling of remaining resources (for printing and fliers) enabled the collective to purchase equipment for inoculation…for all to use”

Project Outcomes

This project has already seen much success in bringing needed knowledge of mushroom production (both indoor and outdoor) to central Indiana and to resource-limited urban farmers. The biggest success of the project so far has been the collaborative network that has been built among farmer partners. Farmers sharing equipment, knowledge, and support has been integral to project success and will continue to help support these and other urban growers into the future. The online platform, Slack, utilized to enhance communication amongst farmers played a large role in maintaining communication between farmers in the beginning of the project when farmers were learning. On this platform, farmers received real-time updates on their phone of incoming messages and were able to share more detailed information via documents and pictures in real-time than would have been possible through text.

On a more practical level, three of the four farms have sold mushroom products, with the fourth recently getting operations underway. We expect all four farms will have enough product to sell at markets this season. This diversification of product offerings will increase farm revenues and diversify local food offerings in Indianapolis. Each farm is producing differently, which has facilitated the creation of a comprehensive assessment of site- and substrate-specific best practices for mushroom production. Each farmer documented their production best practices in factsheets that can be publicly distributed (see enclosed factsheets). Further, farmers learned the soil quality benefits of inoculating vegetable beds with mushroom spawn (such as king stropharia), with each farm benefitting from the initial inoculation conducted at the CUE Farm during the workshop which was subsequently shared amongst farms and integrated into their growing beds.

The most impactful outcomes of the project were twofold. First, farmers that wouldn’t normally collaborate and support one another—either because they work in isolation, are direct competitors, have differing reasons for growing, or are more experienced or less experienced than others—discovered that they benefitted from collaboration around a common goal of mushroom production. We expect these farmer partners to continue collaborating and supporting one another in the future, which may be particularly important for the more inexperienced growers and for growers without support of a larger organization such as a university or non-profit. Secondly, by establishing a clean inoculation room for independent spawn production, farmers have a physical space with which to meet and collaborate, but will also save money and diversity mushroom varieties offered in Indianapolis. More broadly impactful, this local spawn production and planned future training of mushroom production with other urban growers will bolster the local market for mushrooms in Indianapolis.

Farmers reported the following expected future outcomes in the final survey:

Farm 1: “We hope to inoculate our own substrates to reduce costs and increase revenue. We hope to increase production to serve our CSA as well as other markets consistently. We also hope to sell home log kits. We intend to hold workshops for youth take home projects, instructing the benefits of mushrooms to our planet and our bodies.”

Farm 2: “I expect to increase production and sales (though 2019 has taught me that logs won’t necessarily be as easy of a source as I’d expected). And I hope to find ways to integrate mushrooms into the garden.” Note: this farmer had a more difficult time sourcing felled logs from tree companies in 2019 than 2018 suggesting that this waste stream may not be consistently reliable.

Farm 3: “Would love to hold additional workshops on bucket growing and log growing.”

Farm 4: “We hope to put on at least 2 workshops on mushroom production this year. We have 5 youth this summer that will be working on the farm and will learn how to grow mushrooms.”

Given that each of four farmer partners on the funded work has different site opportunities, access to different substrate types, and production scales of interest, it is no surprise that each farmer selected a different approach(es) to mushroom production. This helps strengthen the network of knowledge in Indianapolis on mushroom production over the long-term. All farms are sub-acre urban farms.

Farm 1 has the goal of producing mushrooms year-round using mushroom blocks, fermented straw and sawdust bags, and logs. Over the 2-year project, they gained $500 in revenue and produced 100 pounds of shiitake (logs in natural wood line and sawdust blocks in fruiting chambers) lion’s mane (logs in natural wood line and sawdust blocks in fruiting chamber), and oyster (straw bags) as well as foraged Chicken of the Woods, Hen of the Woods, and Morels. Methods are detailed below.

After the workshop, Farm 1 quickly set up equipment for straw fermentation to inoculate straw bags placed in a shaded hoop house. They inoculated on March 31, experienced first fruit of oysters on May 2, and first full flush on June 6. Once the summer became hot and dry, they experienced difficulty getting fruiting due to climate control.

OYSTERS IN STRAW BAGS: In early October 2017, Farm 1 fermented two additional bales of straw. Two weeks after fermentation began, the straw was inoculated with blue grey oysters. The bales were fully colonized by the beginning of December 2017 and the bags placed in a shaded hoop house to see how the oysters would fair over the winter. The oyster grew very slowly, growing and freezing, then growing and freezing. When they got to market-size they stopped their growth and froze in Indiana’s sub-zero temperatures. While they were frozen they rotted. As a result, Farm 1 has seen a less consistent harvest in the winter months as compared to the other seasons. The consistently get flushes of fruits in spring.

LION’S MANE, SHIITAKE SAWDUST BLOCKS: Farm 1 constructed a fruiting chamber out of a clean IBC tote. Shelves were added to the inside for the sub straight blocks to fruit on and humidifiers blow in moist oxygen to the totes. Five lion’s mane blocks were purchased from Three Caps Mushroom Farm in southern Indiana and placed in the fruiting chamber before the winter holiday season. After January 1, it was determined that the humidifiers were not adding enough moisture to the chambers in the dry winter conditions so pond foggers are now being used where the bottom of the tote is filled with water and the fogger is floated in the tote. This has done the job of adding enough humidity to allow us to get back to a more predictable harvest. Farm 1 has had two flushes of lions mane form the blocks so far at 3 lbs total harvest. The blocks are still producing and moving into their 3rd flush.

Farm 1 planned to purchase up 20 shiitake blocks monthly from Three Caps Mushroom Farm, in southern Indiana. The plan was to receive the 20 blocks around the 11th of each month and placing 10 blocks in their fruiting chambers. After 7-10 days they planned to harvest 8-10 lbs. of mushrooms. The remaining unfruited 10 blocks would then be added to the fruiting chamber. The blocks that produced the first flush would be removed and let rest for 8-12 days, depending on the moisture content. After the blocks are rested they would be punctured 4-6 times with a sterilized probe to create holes for water to penetrate the block when soaked. The blocks would then be soaked for 12 hours to reinvigorate the mycelium and placed in a shaded hoop house or in the wood line to wait for the second flush. As of summer 2018, Three Caps Mushroom Farm is no longer selling blocks. So, in early spring 2019, Farm 1 plans to trial building sawdust blocks using the inoculation lab that was built with the money from the grant award. Farm 1 is also planning to build a climate-controlled room for fruiting, but are not sure when that will be completed given attention that needs directed to vegetable production. They constructed two more fruiting chambers in winter 2018 to increase production.

OYSTER, SHIITAKE, LION’S MANE IN LOGS: In fall 2017, Farm 1 inoculated tree of heaven and placed it in a safe place in their barn so the mushrooms could colonize without insect pressure. When the inoculation sites turned white the logs were moved outside so they could receive water. Using the same method, in winter 2018, Farm 1 inoculated additional logs with oysters, shiitake, and lion’s mane. Expected fruiting spring or fall 2019.

Farm 2 is interested in continuing its focus on growing food in the least resource-intensive ways possible and in harmony with the rhythm of the natural environment. As such, the farm’s goal with mushroom production is to grow 100% outdoor with minimal technology. Farm 2 first focused on log production and placement of inoculated logs in adjacent riparian forest and under fruit and nut trees on site. Over the 2-year project, farm 2 increased revenue by $300 with the production of about 25 pounds of shiitake and oysters on hardwood logs placed in an adjacent riparian forest, with intentionality about not force fruiting and working within the natural rhythms of nature.

SHIITAKE, OYSTER IN LOGS: Farm 2 used Ailanthus logs inoculated with yellow oyster sawdust spawn during the March 2017 training workshop to test success of log placement in adjacent riparian forest. The logs fruited on October 4, 2017 and yielded 8.6 oz of mushrooms. The mushrooms were overripe, so they were given to student interns to consume. Logs were not artificially watered between inoculation and fruiting.

At the end of April and early May, about 30 pin oak and white oak logs were inoculated with shiitake sawdust spawn and placed in adjacent riparian woods. Logs were not artificially watered between inoculation and fruiting. Fruiting occurred in October 2017, and yielded approximately 3.5 lbs of product, with 1 lb tested by the farm manager and interns to assess quality and 2.5 lbs sold at their farm stand for $10/lb.

With the 2017 trial a success, Farm 2 scaled up their log production in the 2018 and 2019 seasons. Production focuses on the spring and fall seasons when the climate is cool and humid and farm product offerings are not as diverse. Farm 2 has been scavenging free freshly cut logs of dormant trees tree trimming companies in Indianapolis. In 2018, this worked well with 150 logs inoculated. Logs have been harder to find in spring 2019 and, as such, only about 50 logs have been inoculated. Since log production takes time for the mycelium to run, the farm hopes to have a large crop of mushrooms in fall 2019 or spring 2020. Over the next year, Farm 2 also plans to convert a damaged, inoperable hoop house into a mushroom log house with high quality shade cloth and stacking frames.

KING STROPHARIA WOOD CHIP INOCULATION: The wood chips that were inoculated with king stropharia sawdust spawn on Farm 2 during the workshop were spread to shaded asparagus rows to explore the opportunity for intercropping asparagus and mushrooms. Wood chips were periodically watered between inoculation and fruiting. Fruiting yield was low, but these mushrooms were more for soil health than market product.

OTHER METHODS: Farm 2 is trialing different ways to incorporate mushroom production into the existing perennial garden, both through intercropping with perennials and inoculating wood chips and compost at the base of perennial fruit and nut trees and shrubs. Almond agaricus will be inoculated into compost. Wine cap inoculated into wood chips. Since Farm 2 is on a college campus, they have been working on a relationship with the campus coffee provider and plan to text the use of coffee grounds as mushroom substrate in buckets in and under the mobile greenhouse on-site. In the future, Farm 2 is interested in researching the growth of oysters on invasive Amur honeysuckle.

Farm 3 has the goal of producing mushrooms year-round. Because this farm has very limited space, they are primarily producing varieties of oyster mushrooms via blocks in fruiting chambers and in buckets under greenhouse benches (golden, PoHu, blue grey, and pink varieties). Golden and PoHu oysters were selected for their larger fruiting temperature ranges and preference for more sun to accommodate the greenhouse growing environment.

Over the 2-year award, farm 3 made about $100 from 20 lbs of oyster mushrooms from fermented straw, coffee, and/or pre-made sawdust blocks. Farm 3 also developed a revenue stream for mushroom growing workshops to homeowners, making $300 off the first workshop. Farm 3 had a shift in personnel in year 2, which slowed down production, but have trained a new farmer to take up mushroom production where the previous farmer left off.

Farm 3 used the knowledge and experience of the Farm 1 to set up equipment for substrate fermentation on November 28, 2017, using in large IBC totes and taking about 2.5 months to produce the first flush of mushrooms. Plastic buckets were used for straw inoculation instead of bags. 13 buckets of fermented straw were inoculated with Pearl Oysters (Pleurotus osteatus) this first round and were placed under a table in the greenhouse to determine fruiting success in those conditions. Buckets were inoculated on November 28, 2017, with first fruiting bodies appearing on February 5, 2018. Even though 20 lbs of mushrooms were produced and sold to restaurants for $12/lb, Farm 3 found this time frame to be a little too early as the mycelium was slow to spread throughout all of the straw and begin fruiting before the process was complete. The first round of mushrooms was harvested on February 16, 2018. For the amount of straw that was inoculated, there was a very meager amount of oysters produced, ~1 lb. While the buckets were watered on a frequent basis and remained in a greenhouse under a table that was watered everyday they tended to not produce large fruit bodies.

In hopes of a larger production amount, Farm 3 used heat-treated straw stuffed into large bags to hanged under the tables of two greenhouses. In March 2018, three bags of PoHu and two bags of golden oyster will be inoculated every two weeks to get staggered production. Bags will be filled with heat-treated straw as fermenting is hard to achieve in the winter. However, these bags never produced any mushrooms possibly because of the lack of controls in terms of the environment.

In February 2018, Farm 3 also carved out a bit of space in their indoor storage to experiment with a fruiting chamber. For the fruiting chamber, a large 6×6 foot commercial metal shelf was converted into a fruiting chamber for mushroom blocks where the shelf is covered with plastic to create the fruiting chamber and a pipe hanging off the side of the chamber will be connected to a 40 gallon plastic tote on the top shelf where a pool of water and an ultrasonic pond fogger will be located. On the side of the tote lid opposite the fogger outlet, there will be an inline duct fan to circulate moist air in to the chamber as well as push out some of that CO2 out of the bottom of the chamber. The chamber is on timers to regulate humidity and CO2 so that it is self-contained and automated to avoid the need to manually mist mushroom blocks with water twice a day. This fruiting chamber was first used to fruit sawdust blocks of shiitake and lion’s mane ordered from Three Caps Mushroom Farm in southern Indiana. In early spring 2018, the farmer from farm 3 leading mushroom production, left his employment. This slowed down production however, two farmers at farm 3 are picking up where the original farmer left off.

In the future, farm 3 is definitely open to continuing to produce mushrooms as an income generator on the farm however, they are not actively pursuing it given time constraints with vegetable production and education. Because farm 3 had limited space (< 0.5 acres and a small greenhouse) and is located at a high school and fitness center, it was difficult to keep the environments ideal for mushrooms production. As a passive project it may be something they continue working on in our free time.

Farm 4 has a goal of producing mushrooms year-round for their local neighborhood, which is a food desert. Farm 4 is a new urban farm that was still acquiring land from tax sales when the project began in March 2017. This farm spent the first year researching mushroom production and markets and conducted some small trials in the backyard of a home while waiting for the property purchase to be finalized. The property has now been acquired and the farm purchased a propane turkey fryer at the auction to sanitize substrate (in this case, straw) in a 55-gallon drum via boiling. In March 2018, farm 4 started collecting coffee grounds from local coffee shops. They are currently testing the viability of inoculating coffee grounds in buckets. In fall 2018, Farm 4 retrofitted a hoop house with shade cloth and enclosed ends; an approach that is also being explored by farm 2. Farm 4 also has five youth this summer assist with production. Because Farm 4 was a beginning farmer with limited resources, it took time to gather all the infrastructure needed to begin production. To date, this farm has successfully inoculated straw with multiple varieties of oyster mushrooms in straw and coffee grounds under a converted hoop house and has had success producing approximately one pound of mushrooms ($0 in sales).