Final report for ONC18-045

Project Information

Nebraska’s growers are struggling to integrate sustainable cropping systems vs. the customary corn and soybean systems. Primarily because of economic and climate constraints, crop rotations have not changed.

We explored the viability of malted barley production. Expanding crop diversity with barley would impact soil biology, increase unique residue covers and enhance soil resiliency. It would also allow double cropping through legumes or grazing cover crops.

Winter barley production in Nebraska has been unreliable primarily because of winter kill. Dr. Stephen Baenziger’s research, University of NE-Lincoln, is demonstrating initial success with barley production. He is introducing new and hardier varieties that are adapted to our climate. We compared forms of nutrients and examined interplay with soil temperature, moisture and surface air temperature as well as determine if the barley meets brewers’ specifications.

It appears that the combination of improved genetics and soil cropping systems managed to mitigate climate impacts will sustain winter barley production in Nebraska. There are still two major challenges to proving if this crop is economically viable: 1) the market for a premium buyer requires significant logistical investments of time and infrastructure; and 2) managing planting, spraying, and harvest within a corn-bean rotation more often than not leads to less than desirable planting dates.

- Determine if winter malted barley is viable to crop rotations in Nebraska and is economically sustainable

- Examine the impact of prior crop rotations upon the physical, biological and chemical properties of the soil and weather resiliency

- Assess the impact of barley upon soil and air temperature and soil moisture

- Compare nutrients and identify the fertility requirements for Nebraska's soils that meet barley brewing standards

- Determine if malted barley can be grown to meet brewing standards

- Establish a network and contact list for barley producers with the brewing industry

Cooperators

- (Educator)

Research

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Primary means of outreach is a blog, Big N Barley Men. The site catalogs an experiment growing and evaluating the viability of winter malted barley production in Southeast Nebraska. We will introduce you to some Big N Barley Men: those who are growing barley through sustainable ag practices, scientists breeding barley for Nebraskans, agronomists monitoring fertility and quality, and the maltsters and craft brewers utilizing the barley. Outreach measurement is through site traffic.

Secondary means of Outreach has been through the Nebraska Sustainable Ag Society List serve. Farmers have independently requested assistance with growing and marketing barley through this site.

Rigg and McDonald were presenters at the Nebraska Climate Summit on 21 March, 2019 in Lincoln, NE. This event and webinar had 175 attendees. 55 attendees were ag professionals, 25 were farmers and the remaining were from environmental and health organizations. The presentation is available on YouTube. The Summit provided an opportunity to consult with two farmer land owners as well.

Additionally, in February 2020, soil samples were collected to evaluate high sodium content associated with glacial till soils in southeast Nebraska. This inquiry came from the Syracuse USDA NRCS field office. We are working with the field office to develop new seed mixes following terrace construction that includes barley to recover salt affected soils sooner.

Learning Outcomes

Seeding rates for winter barley

Direct Marketing Constraints

Project Outcomes

Here is a summary of our performance of project objectives, this section of the report with links to the project blog include additional details:

- Determine if winter malted barley is viable to crop rotations in Nebraska and is economically sustainable

- The crop is viable even when planted later than recommended

- Economic viability was not easily recognized

- The direct sales as malted barley did not come to fruition with any regularity or high demand

- Some of the barley was grazed or harvested as forage to recover costs

- There is uncalculated but assumed benefits of cover and nutrient cycling for following crop

- The sale of certified seed as a cover crop or for replanting seems to be a viable option

- Examine the impact of prior crop rotations upon the physical, biological and chemical properties of the soil and weather resiliency

- Crop residue seemed to play the most significant role in weather resiliency when winter weather was most severe

- High residue also buffered the impact of hot, dry conditions too

- Lower residue levels seem to benefit over-winter production in mild winter conditions, as in year 2

- it is too early to determine if heat/drought will impact the crop in low residue conditions

- Crop residue seemed to play the most significant role in weather resiliency when winter weather was most severe

- Assess the impact of barley upon soil and air temperature and soil moisture

- We were not able to detect a difference in water use between cropping systems to determine if barley depleted soil moisture reserves

- The residue levels kept soil temperatures lower in barley systems compared to corn and soybean cover in early summer

- Compare nutrients and identify the fertility requirements for Nebraska's soils that meet barley brewing standards

- There was inadequate harvest data to compare to fertility management for the project

- Recommended fertilizer rates cannot be determined

- It is unknown what value synthetic or organic fertilizers have on influencing grain quality over the inherent soil mineral properties of Nebraska soils

- Determine if malted barley can be grown to meet brewing standards

- brewing standards were met with little additional effort to fertility management

- The primary failed standard was vomitoxin

- This only occurred on fields where fungicides were not applied

- Establish a network and contact list for barley producers with the brewing industry

- This was an underestimated challenge described in the body of this report

The primary outcome recognized in the first year is the use of weather stations to evaluate residue management practices. By having local data on farms and with farmers other growers recognize, we hope to relate our data to other research and continue to promote sustainable soil health practices. The primary collaborator has been with Dyacon, Inc, the manufacturer of the weather stations we purchased.

This working collaboration has lead to Dyacon expanding operations into the Midwest agriculture sector. Dyacon has developed a series of reports for our use in monitoring weather and climate change for agriculture decision making.

In addition, we have used the Nebraska MESONET weather stations and integrated them into our operations and monitoring.

Starting with the initial grower kick off meeting a primary concern regarding marketing and direct sales was identified by all four participating growers. Unlike the customary row crops for the region, the sales market was limited to direct sales to malteries, craft breweries, and home brewers for grain that meets malting quality standards. The concern was even greater for sales and use of grain that did not make quality standards.

A blog was set up in the first month to describe the project and gradually introduce the objectives with detail. Initially, interest in the project was positive especially from restaurant and craft brewers. But it was easy to see there would be challenges with establishing a grower/buyer community.

An additional challenge was identified concerning marketing within the first few months of the project. The group of growers did not have dedicated resources for marketing and advertising. While the blog generated limited interest and was received well, it was more science based and didn't seem to appeal to customers. Also, the cost of having a marketer appeared to exceed the potential gain. In-fact, as we evaluated traffic to the site, it appeared subscribers rarely viewed the site and incidental traffic was not often followed. Besides, my own mother, I don't think we had any regular visitors to site following postings.

Prior to planting the first winter barley crop, some growers raised concerns about storage. With a limited market, the purchasers did not provide substantial storage and growers could not justify taking up commodity crop bin storage for the barley. This would require using 60,000-80,000 bushel bins to store 1,200 bushels of barley.

Additionally, the purchasing market is still an emerging start-up business. This local industry cannot manage risk at this point to enter into multiple guarantee contracts. The growers were tasked with developing and investigating additional markets to ensure a buyer after harvest.

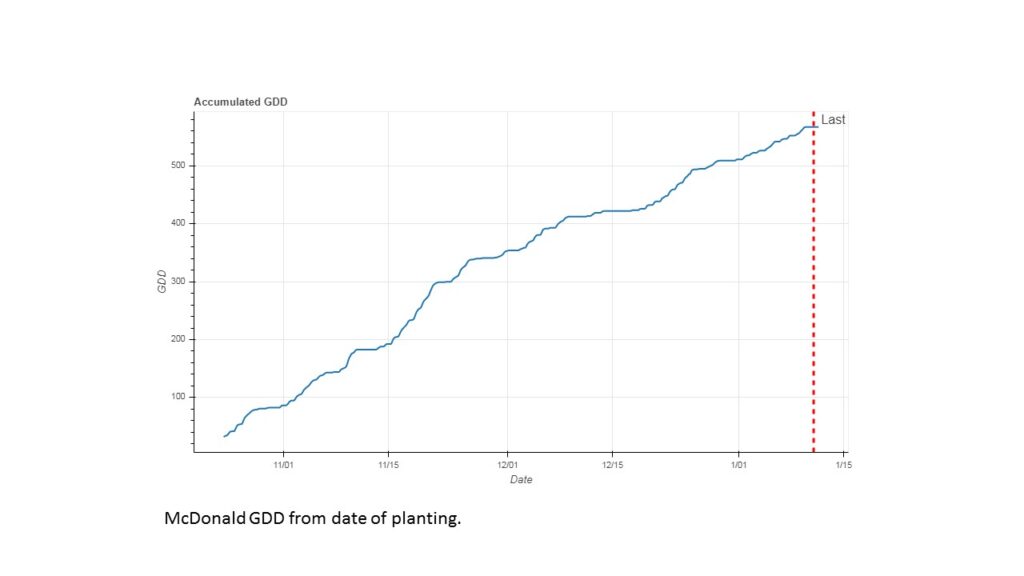

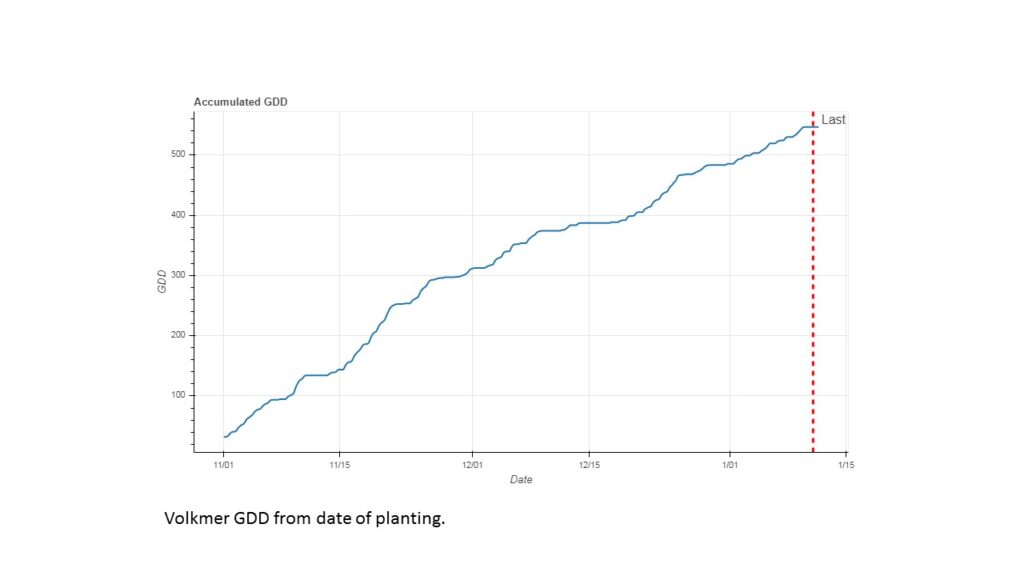

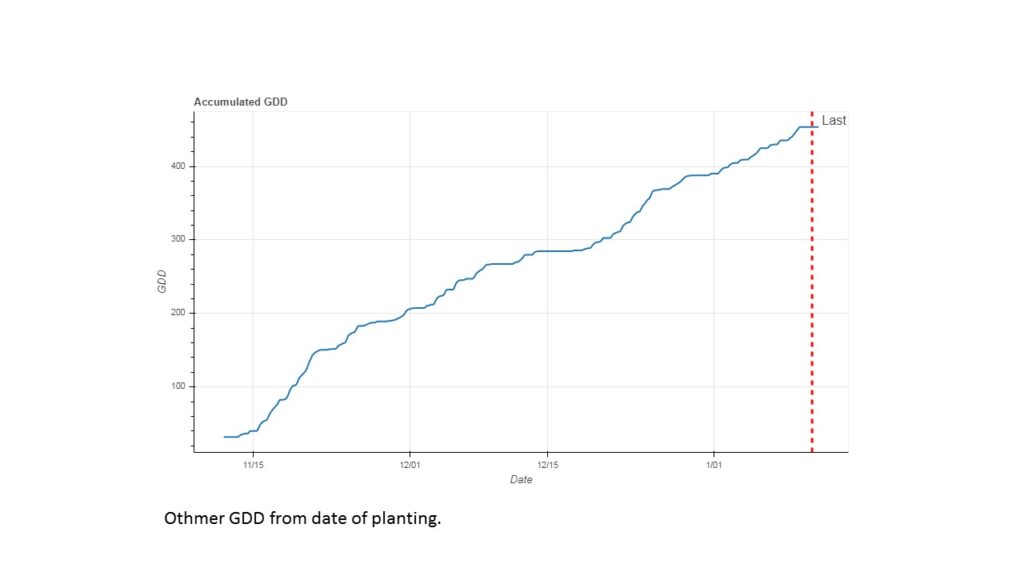

All growers had a difficult time getting their first year crop planted. Excessive moisture at the time of corn and bean harvest delayed getting the fields open for planting. Half of Volkmer's trial was planted in September, Volkmer's remainder, Brehm, and McDonald didn't get planting complete until late October. Othmer was extremely delayed and didn't plant until 15 November. All October plantings germinated within 2 weeks. Snow covered Othmer's before it could be checked for germination.

An effort was made to clean, hull, and grind barley for use in restaurants. We were moderately successful in hulling the barley with hand equipment, but grinding for flour was not successful. The moisture content appeared to be too high and overheated and clogged small commercial grinders. The labor required to hull the barley took about two hours to produce 5 pounds of clean, hulled grain. With our current resources, we have determined that processing the grain for culinary use can only be done as an novelty or as part of the outreach effort.

Outreach efforts in the first year fell flat. We anticipated, based on discussions with brewers and industry representatives at conferences, there would be interest from local malters and home brewers in local grain. We made multiple attempts to contact the target audience for this grant and did not received responses back. The reality we discovered is: the local emerging craft brew industry is tied to a combination of restaurants and agro tourism. The demand on business owners time is significant, we could not compel them to give us time for marketing grain when it amounts to such a small component of their product.

The first year's outreach was limited to the project blog. The level of effort in maintaining the blog was reduced due to limited results and traffic to the site. One of the first project lessons learned: a significant effort with marketing and combining social media platforms is necessary. Our group had no expertise or resources to complete such an effort.

First year harvest results were relatively poor. Two growers, McDonald and Othmer, did not have adequate stands to bring to harvest; Othmer treated his stand as a cover crop and McDonald allowed his to grow with other companion crops to harvest as forage.

Thomas Volkmer harvested about 8-9 acres of barley that was planted early last year; the remaining acres that were planted later were terminated and planted to beans. The harvest date was July 2 and a double-crop of soybeans was planted July 3! Volkmer estimates about 50 bushel per acre barley harvest.

![IMG_20190707_153234[1]](https://bignbarleymen.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_20190707_1532341.jpg)

![IMG_20190707_153400[1]](https://bignbarleymen.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_20190707_1534001.jpg)

Randy Brehm left some of his higher density winter barley that was planted significantly later than Volkmer's. It appeared to be about a week or 10 days slower to mature but was a significantly thinner stand with greater weed pressure.

We were able to prove the winter hardiness of winter barley. This cold spring provided a gradual warm up rather than cycles of warming and cooling that would have put plants at greater risk to freeze kill.

The stands were more susceptible to Fusarium Head Blight than we had first predicted based on the spring barley harvest from 2018.

The second year of planting was more timely than year one for most growers. The growers were able to anticipate the challenge of switching between harvest and planting better and prioritized the activity. McDonald planted on 10/24/21019, Othmer planted 11/12/2019, and Volkmer planted on 11/1/2019. This allowed for plenty of GDD to get a good start. In fact McDonald had emergence within the first 10 days.

Near the end of the period we had for monitoring this trial, plant stands appeared healthy. We had significantly less snow cover than the prior winter which may end up causing more winter kill even with significantly milder temperatures.

|

Measurement |

Average |

High |

Low |

|

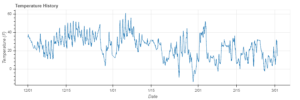

Temperature (F) |

24.8 |

61.2 |

-13.5 |

|

Humidity (%) |

80.0 |

100.0 |

32.0 |

Temperature from December 2018 - March 2019

|

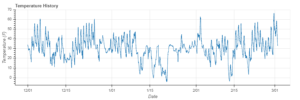

Measurement |

Average |

High |

Low |

|

Temperature (F) |

30.2 |

66.6 |

-4.2 |

|

Humidity (%) |

75.0 |

100.0 |

19.0 |

While we would love to have nothing but positive results to demonstrate soil health practices, the photos below depict a benefit to early and consistent emergence in darker surface soils.

One beneficial finding from the fertilizer component of this project comes from Mike McDonald's trial site. The application of compost and manure mimics the beneficial effect of residue disturbance while ensuring the soil surface and residue remains intact.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBbEm4HsmOg&list=PLS54zJxfQBy6KsoNMg-AQS5eyaHIjo3P4&index=7

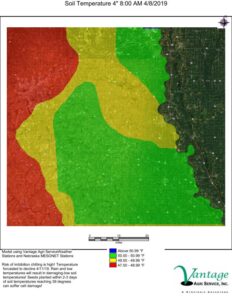

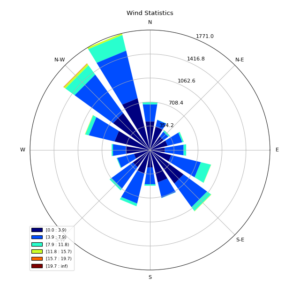

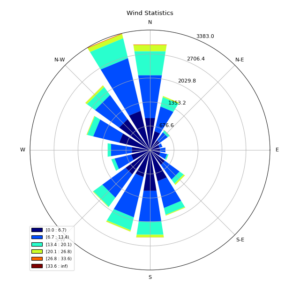

As we monitored weather and soil conditions with the project weather stations, other growers outside of the project became interested in monitoring weather for their production purposes. Growers became interested and aware of soil temperature differences in short geographic proximity and especially wind differences.

Discussions concerning global climate change became more relevant when data from farms that local growers are familiar with could relate to. The agriculture advisers on this project could use the weather data to initiate discussions with more conventional growers about climate-smart decisions concerning planting and pesticide use.

There appears to be significant benefit to monitoring weather data specific to local areas. The weather instruments used for this project have monitored differences in air and soil temperature and wind speed and direction between sites.

Specific to wind, the instruments used for this project measure wind speed closer to the ground surface than National Weather Service or airport station. These stations are more reflective of the conditions that agricultural managers encounter when applying pesticides and other inputs.

Development of county-wide, real-time, networks with agricultural weather stations may significantly benefit managers. A local weather network established for agricultural purposes by agricultural users can shape decisions for commercial applicators and independent growers.

Additionally, monitoring local trends can demonstrate weather changes and trends associated with climate change. Climate change has become a highly politicized term and for many growers aligns a prejudice which can adversely impact decisions. Often when discussing the weather, many growers acknowledge changes in weather severity, but may not align with or support management for Climate Change. A local network of weather monitored, with recommendations provided by local agricultural professionals may improve decision making.

Based on our early results from the first 2 years with 5 weather stations in operation, we will likely pursue implementing more stations and improving our ways to distribute decision making data to a wide range of producers. This range of producers will include groups outside of those traditionally participating in sustainable agriculture activities.