Final report for ONC22-104

Project Information

Tillage-based corn-soy rotations are the dominant cropping system and represent the major land-use type throughout the Big Blue/Little Blue River watershed in Kansas and Nebraska. The amount of tillage, coupled with relatively high rainfall amounts and intensities, leads to significant soil and nutrient loss to runoff and erosion. Continued soil and nutrient loss to erosion and runoff threatens long-term farm productivity and impairs the quality of surface and subsurface water for human consumption and recreational activities throughout the watershed. Perennial groundcovers (PGC), also known as perennial cover crops, may provide a sustainable alternative to tillage-based production systems and may prove to be more resilient and cost-effective than winter annual cover crops.

We plan to plant kentucky bluegrass and kura clover PGC at three farms in the Big Blue/Little Blue watershed and to collect economic and soil health data. Our research addresses the questions: “Can corn-soy planted into PGC be profitable and a pathway to ecological intensification in the watershed?” and “What barriers to adoption require future research and innovation?” All researchers and farmers will collaborate to introduce knowledge about PGC and our project to the watershed by sharing findings at field days, on social media, and at extension meetings.

PGC research: Determine the agroecological viability of corn/soy planted into kentucky bluegrass and kura clover perennial groundcovers under different farming strategies in Kansas and Nebraska.

- Soil Health: Evaluate effects of PGC on soil health and carbon sequestration compared to conventional practices.

- Economic Analysis: Compare productivity and profitability under different PGC management strategies - kura clover PGC, kentucky bluegrass PGC, and conventional management.

PGC Outreach

- Build local stakeholder awareness and engagement around PGC.

- Host field days in KS and NE to engage with the local community about PGC.

- Publish our findings on PGC profitability and soil health.

Cooperators

Research

Narrative of Establishment Attempts

The project began in fall 2022 with the goal of establishing perennial groundcovers on working farms in Kansas and Nebraska. Four producers - three in Kansas and one in Nebraska - agreed to host paired 2-acre plots of Aberlasting clover and Kentucky bluegrass within their corn or soybean fields. The intention was to evaluate how well these perennial groundcovers could be incorporated into normal corn and soybean production for improved erosion control and nutrient management.

Iteration 1: Fall 2022 Drone Seeding

The first attempt at establishment relied on a drone equipped with a broadcast spreader. On September 7, 2022, the drone flew each of the four farms, dropping either Aberlasting clover (12.5 lb/ac) or Kentucky bluegrass ‘Milagro’ (10 lb/ac) directly into standing soybeans. Drone seeding was chosen because it minimized soil disturbance and avoided late-season field passes, allowing seed to be applied even under a full crop canopy. Despite its logistical advantages, the fall 2022 seeding coincided with an exceptionally dry period across Kansas and parts of Nebraska. The seed landed mostly on dry residue and dusty soil surfaces, and with little moisture available to trigger germination, almost no seedlings emerged. All three Kansas sites failed to establish any meaningful stand, and although the Nebraska site showed a few scattered seedlings, it was also insufficient for the purposes of the trial. This first establishment experience made it clear that drone broadcast seeding, especially of these small perennial grass and legume seeds, is highly dependent on late-season soil moisture. It is likely highly risky in non-irrigated locations, especially in a dry fall.

Iteration 2: Spring 2023 Replanting (No-till Drill)

Two of the producers - one in Kansas and one in Nebraska - were willing to try to replant the trial in spring 2023. This time, a no-till drill was used in March to place seed firmly into the soil. As in the fall attempt, the plots were kept separate by species, with blocks of Aberlasting clover and Kentucky bluegrass laid out in the same configuration as before. The drill provided reliable seed to soil contact and took advantage of early spring moisture, giving both species a fair chance to establish. However, shifting the planting window to spring created a new weed management challenge. The cooperating farmers could not apply their usual pre-emergent and burn-down herbicides before planting corn because they were waiting for the perennial groundcover seedlings to germinate and establish. Without a burndown and pre-emerge program, an aggressive flush of early-season broadleaf weeds quickly took hold in both the Kansas and Nebraska plots.

By the time the corn was planted, weed pressure had become substantial. As weeds continued to grow into the early vegetative stages of corn, farmers ultimately had no choice but to apply post-emergent broadleaf herbicides—primarily dicamba or 2,4-D—to protect their cash crop. These herbicides controlled the weeds effectively but also killed the clover, eliminating the legume groundcover component of the trial. Some Kentucky bluegrass plants survived, but stand quality deteriorated under heavy competition. This establishment iteration demonstrated that spring-established perennial groundcovers are not compatible with typical corn burn-down and pre-emergent herbicide programs. Furthermore, it revealed particular challenges in managing broadleaf weeds in fields with a clover perennial groundcover once they have become established because of the lack of chemistry to target the broadleaf weeds without harming the clover.

Iteration 3: Fall 2023 Drilled Kentucky Bluegrass in Nebraska

Recognizing that perennial legumes were too vulnerable to commonly used broadleaf herbicides, the project shifted its focus to Kentucky bluegrass, a grass species that aligns more naturally with standard pre- and post-emerge programs. In fall 2023, the Nebraska cooperator no-till drilled Kentucky bluegrass into soybean stubble at 20lb/acre seeding rate in mid October into two additional field locations. The producer set the drill to seed at the shallowest setting and took all the hydraulic down pressure off the drill to ensure that the seed was not planted too deep. These two locations were then irrigated in the fall with a pivot, and uniform stands across all three drilled fields (one spring and two fall) were established in Nebraska by spring 2024 to allow the project to proceed with monitoring yield and soil health changes.

Cash crop management

Across all three growing seasons (2023–2025), cash crops in the perennial groundcover (PGC) plots were established and managed using the cooperating producer’s standard strip-till and planters, with only minimal adjustments to accommodate the living groundcover. Each spring, prior to planting corn (or soybeans), the farmer strip-tilled the PGC and control areas using a Schlagel 10-inch-wide strip-till unit, operated at a depth of 6–7 inches. Strip-till provided a warm, well-mineralized seedbed free of competition from the perennial groundcover for the cash crop.

During strip-till, the producer applied 120 lb N and 40 lb P as liquid fertilizer directly into the strip for the corn. These nutrient rates were identical to those used across the larger field and reflected the farmer’s normal fertility program for achieving commercially competitive corn yields. Using the same fertility strategy in PGC and conventional strips ensured fair yield comparisons. To temporarily reduce early-season groundcover competition, the project used Liberty herbicide (glufosinate) as the primary suppression tool. Liberty was applied at a rate of 22 oz/acre with a 20-gallon carrier volume. The product was selected because it is a contact herbicide that effectively burns down leaf tissue without translocating to the roots. As a result, the Kentucky bluegrass groundcover turned brown and was set back temporarily, but it was not killed. This gave the emerging corn or soybean crop a competitive head start while allowing the perennial groundcover to survive and regrow later in the season. Liberty was applied either just before planting or just prior to crop emergence, depending on field and weather conditions.

Following crop emergence, all other herbicide, fertility, and pest-management operations were identical to the surrounding commercial field. The only major restriction in the system was the avoidance of glyphosate (Roundup), which would have killed the Kentucky bluegrass groundcover. Aside from excluding glyphosate, the herbicide program followed the producer’s normal weed-control strategy for the crop and geography.

Data Collection

2023 Corn Yield (Spring-Established KBG Field)

The first usable yield dataset came from the Nebraska field where Kentucky bluegrass had been drilled in spring 2023. Although the companion clover plots in this iteration were later terminated due to herbicide requirements, the bluegrass plots survived long enough to carry through to corn harvest. Yield was collected directly from the farmer’s combine yield monitor as the crop was harvested in the fall of 2023.

2024 Corn Yield (Spring and Fall 2023 Established KBG Fields)

The most complete yield dataset was collected in 2024, after Kentucky bluegrass successfully established across the three Nebraska field locations (one drilled in spring 2023 and two drilled in fall 2023). Corn was planted directly into the perennial groundcover the following spring using the management practices described above.. At harvest, the producer again recorded yields using the combine’s yield monitor. Across the three fields, this generated six replicated comparisons between perennial groundcover and conventionally managed blocks.

2025 Soybean Yield (Plot Combine; Multiple Genotypes)

In 2025, soybean yield data were collected from the same spring-established location used for 2023 corn. This field had been planted to a diverse set of soybean genotypes by a collaborating partner. Because of the small-plot layout needed for the genotype trial, soybeans were harvested using a plot combine, allowing precise measurement of yields from replicated comparisons across the PGC and control areas.

Soil Health Data Collection

Soil health sampling occurred near the end of the project, in late summer 2025, after the perennial Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) had been established for nearly two full years across the three Nebraska field locations. By the time soil samples were taken, the groundcovers had been present on the land for two winters and two cash-crop growing seasons.

Soil sampling targeted the biologically active 0–6 inch depth, where perennial groundcovers typically influence organic matter inputs, aggregation, nutrient cycling, and soil moisture dynamics. Across all three Nebraska fields, soil was collected from both the Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover strips and the adjacent conventionally managed control strips. For each treatment in each field, three replicated composite samples were collected, resulting in a total of 18 samples (3 fields × 2 treatments × 3 reps). All soil collection followed the published methods of RegenAg Lab (Pleasanton, NE). Soil samples were submitted to RegenAg Lab to be analyzed for a suite of physical, chemical, and biological indicators, including: the Haney Soil Health Test, Wet Aggregate Stability, Water Holding Capacity (WHC), and a routine Soil Chemistry Panel.

Cash Crop Yield Performance

This project generated three years of yield data across corn and soybean rotations. Each dataset reflects a different stage of perennial groundcover (PGC) establishment and provides insight into how establishment timing and perennial groundcover maturity might influence crop performance under commercial management.

2023 Corn Yield – Spring-Established Kentucky Bluegrass

The first yield dataset came from the Nebraska field where Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) was drilled in spring 2023, only a few months before corn planting. This represents a spring planted perennial groundcover scenario.

Corn yield in the PGC blocks averaged 225.4 bu/acre, compared with 229.5 bu/acre in the adjacent conventional strips. The yield difference was - 4.1 bu/acre (KBG relative to control). Because these data came from a single site with a newly established groundcover, no statistical conclusions were drawn. However, we observed that the Kentucky bluegrass was not as vigorous in this field during 2023 as it was in subsequent years after full-establishment, and therefore, it may not have exerted as significant of a competitive effect on the corn in 2023.

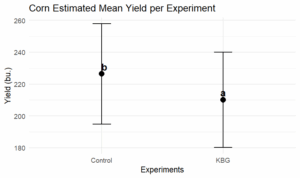

2024 Corn Yield – Fall-Established KBG Across Three Fields

In 2024, corn yields were collected from the Nebraska producer’s three fields where Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) had been drilled in spring and fall 2023. These fields had mostly mature Kentucky bluegrass by the time it was strip-tilled and planted into in spring 2024. The corn yield in the PGC blocks averaged 210.1 bu/acre, compared with 226.4 bu/acre in the conventional blocks (Figure 3). The yield difference was - 16.3 bu/acre (KBG relative to the control). Corn height followed the same pattern, averaging ~ 96 inches in the control compared to 93 inches in the KBG planted corn. A statistical analysis of the 2024 dataset found the Kentucky bluegrass corn yield to be significantly less (P = 1.688 × 10⁻⁵) than the conventional corn treatments. The 2024 results illustrate that a fall-established perennial groundcover can exert measurable competitive pressure on corn, even under realistic fertility and herbicide programs that include spring suppression of the Kentucky bluegrass with glufosinate herbicide. In this particular year and location, the Kentucky bluegrass decreased observed corn yields by approximately 7%.

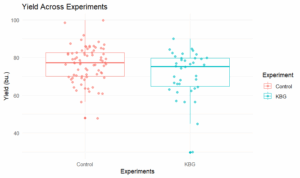

2025 Soybean Yield – Spring-Established KBG System

Soybean yield was evaluated in 2025 at the same Nebraska field where KBG was drilled in spring 2023 (Figure 4). This field was planted to multiple soybean genotypes in a variety trial design by a collaborating partner, and yields were obtained using a plot combine. The field had a very mature stand of Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover in spring 2025 when it was strip-tilled and the soybeans were planted.

The mean soybean yield in the Kentucky bluegrass blocks (across all genotypes) was 72.6 bu/acre, compared with 75.8 bu/acre in the control blocks (Figure 5). The yield difference was -3.2 bu/acre (KBG compared to the control). Soybean height followed a similar pattern with soybean plants averaging 33.0 inches tall grown in the KBG vs. 35.5 inches tall when grown in the control environments. Mixed-model analysis of these data showed no significant main treatment effect of KBG vs. control soybean yield (χ² = 3.959, df = 2, P = 0.138); however, a significant genotype x environment (GE) interaction was observed in how soybean genotypes yielded in the KBG vs control environments ( χ² = 36.842, df = 9, P = 2.81 × 10⁻⁵).

Soil Health Results

Soil samples were collected in late summer 2025 from all three Nebraska fields where Kentucky bluegrass had been established for nearly two full years. Samples were taken from both the perennial groundcover (PGC) strips and the adjacent conventional blocks to evaluate whether the perennial living cover was beginning to influence soil biological, physical, or chemical properties. Overall, the results showed no statistically significant differences between the KBG groundcover and the conventional management across any of the measured soil health indicators. This outcome is consistent with expectations for early-stage perennial groundcover systems, which typically require several years before measurable soil changes appear.

Table 1. Soil sample mean and standard deviations from control (no perennial groundcover) and Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover treatments in on-farm trials in Nebraska taken in late summer 2025.

|

Soil Indicator |

Control (Mean ± SD) |

KBG (Mean ± SD) |

|

Soil Organic Matter (%) |

3.38 ± 0.44 |

3.84 ± 0.62 |

|

Total Organic Carbon |

231.6 ± 34.4 |

246.3 ± 42.0 |

|

Haney Soil Health Score |

11.2 ± 1.7 |

11.6 ± 2.1 |

|

Available Nitrogen (ppm) |

51.9 ± 12.2 |

52.3 ± 16.2 |

|

Available Phosphorus (ppm) |

156.1 ± 227.5 |

120.7 ± 125.3 |

|

Available Potassium (ppm) |

261.8 ± 59.0 |

256.5 ± 71.3 |

|

pH |

6.69 ± 0.26 |

6.76 ± 0.29 |

|

CEC (meq/100 g) |

12.91 ± 3.57 |

14.01 ± 3.59 |

|

Water Holding Capacity (g/g soil) |

0.235 ± 0.034 |

0.238 ± 0.036 |

|

Microaggregate Stability (%) |

33.5 ± 10.7 |

40.2 ± 15.1 |

|

Macroaggregate Stability (%) |

42.7 ± 8.0 |

37.7 ± 11.4 |

|

Total Aggregate Stability (%) |

76.2 ± 3.8 |

77.8 ± 5.4 |

Soil organic matter, total organic carbon, and the Haney Soil Health Score were similar between the perennial groundcover (KBG) and conventional treatments (Table 1). Although the KBG plots had slightly higher mean values for some carbon-related measurements, field-to-field variability was large enough that none of these differences were statistically significant. Nutrient availability—particularly nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium—was nearly identical between treatments, and soil pH and cation exchange capacity showed no meaningful divergence. These findings suggest that neither the presence of perennial roots nor the modified herbicide program had influenced baseline soil chemistry or microbial activity within the first two years of establishment.

Physical soil properties also showed no significant treatment effects. Water holding capacity was essentially the same in both systems, and aggregate stability differed only slightly, with KBG showing small numerical increases in microaggregates and total aggregates (Table 1). While these early trends are consistent with expected long-term benefits of perennial roots, they were not large enough to be statistically detectable at this stage. Taken together, the results indicate that two years of Kentucky bluegrass groundcover were not sufficient to produce measurable changes in soil chemistry, biological activity, or physical structure at the 0–6 inch depth. However, minor increases in soil carbon and microaggregate stability may represent early signals of improvement that could become more pronounced with continued groundcover persistence and additional years of management.

Perennial Groundcover Cost Analysis

A key objective of this project was to understand the economic implications of using Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) as a perennial groundcover in corn-soy rotations. To evaluate the economics clearly, we separated the analysis into two components: the cost of implementing each system and the revenue impacts caused by yield differences observed in our on-farm trials. This distinction helps clarify where perennial groundcovers add cost, where they save money, and how they perform in terms of crop productivity.

1. Cost Comparison Across Systems

The cost of adopting a cover crop varies depending on whether the crop must be replanted each year. Annual cover crops, like rye, require new seed and drilling every year. Conversely, perennial groundcovers, like Kentucky bluegrass, can be seeded one time and then persist through multiple cash-crop growing seasons. Over a typical three-year corn–corn–soybean rotation, annual rye (assuming it is planted each year in the rotation) can actually cost more to implement than a Kentucky bluegrass PGC because it requires seed, drilling, and termination every year (Table 2).

Table 2. Perennial groundcover and cover crop management and input costs in a 3 year corn-corn-soy rotation.

| System | Seed Cost | Drill Cost | Herbicide Suppression or Termination Cost (3 years) |

Total Cost (3 years)

|

| No cover | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Annual rye | 40 lb/ac × $0.28/lb × 3 years = $33.60 | 3 years × $25 = $75 | 3 years × $7 glyphosate = $21 | $129.60/ac |

| Perennial KBG | 15 lb/ac × $2.05/lb = $30.75 | $25 (one time) | 3 × $17 glufosinate = $51 | $106.75/ac |

Over three years, KBG cost about $23 per acre less in inputs than annual rye over a single corn-corn-soy rotation. Field observations during this project showed that Kentucky bluegrass established into a dense, rhizomatous sod that would likely persist for at least another full corn–corn–soybean rotation without needing to be replanted. When we extend the economic window from three years to six years, the perennial nature of KBG becomes a major cost advantage over continuous replanting of a rye (or other annual cover crop) over two corn-corn-soy rotation cycles (~$152 per acre in savings).

2. Revenue Impacts Caused by Yield Differences

While costs describe “what it takes to do the system,” revenue reflects how the system performs agronomically. The yield data collected in these on-farm trials demonstrated that KBG reduced grain yield in each of the years of the corn-corn-soy rotation. Translating these yield differences into dollar values gives a more complete picture of profitability (Table 3).

Table 3. Approximate gross revenue impact of Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover management compared to control (no perennial groundcover) in Nebraska on-farm trials.

| Year | Crop | Yield Penalty (bu/ac) | Approx. Price | Revenue Loss |

| 2023 | Corn | –4.1 | $4.88/bu | –$20/ac |

| 2024 | Corn | –16.3 | $4.40/bu | –$72/ac |

| 2025 | Soybean | –3.2 | $10.50/bu | –$34/ac |

Total 3-year gross revenue showed an ≈ –$125/ac loss when managed with a Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover.

In Nebraska, published on-farm research and modeling studies generally show neutral to slightly negative effects of cereal rye on corn yield when rye is terminated 10–14 days before planting, with most site-years reporting 0–4% yield differences compared to no cover crop (UNL Crop Watch, 2022). However, studies also consistently demonstrate that late termination of rye can result in substantial yield penalties, sometimes reaching 25–30%, due to early-season competition and nitrogen immobilization (Oliviera et al., 2019). Against this backdrop, the ~7% corn yield reduction we observed with a fully established Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover places our results between the typical early-terminated and late-terminated rye outcomes. Given that these were some of the first on-farm trials of perennial groundcover systems in Nebraska, the results are encouraging. They suggest that, as with rye, refinement of suppression timing, nitrogen placement, and groundcover vigor management could substantially reduce competition and improve crop performance. With improved spring suppression strategies, which is analogous to shifting from late to early rye termination, it may be possible for perennial groundcovers like Kentucky bluegrass to achieve yield-neutral or near-neutral performance, similar to the well-managed rye systems already adopted by many Nebraska producers, and therefore also achieve gross revenue parity.

3. Integrating Costs and Revenues: Short-Term and Long-Term Outlook

When we combine costs and yield effects, the short-term (first three years) economics of perennial KBG are challenging. Although KBG costs slightly less to establish than rye, the grain yield penalties in 2023–2025 more than offset those savings. In total, we observed $125/ac in lost revenue + –$106.75/ac in management costs over the three year crop rotation with Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover (i.e. - $231.75 less profitable than no cover crop). With a rye cover crop, we would have had –$129.60/ac in management costs, but potentially no lost revenue due to yield loss.

The long-term story begins to change once we consider the potential for persistence through additional rotations in the Kentucky bluegrass perennial groundcover. If Kentucky bluegrass persists for another full rotation (as we observed), it becomes:~$ 101/ac cheaper than rye in establishment + herbicide cost over the six year period. If Kentucky bluegrass can be managed at the same 0-4% cash crop yield loss as was reported for rye (i.e. the same gross revenue is achieved), it can be an effective lower cost option for corn-soybean rotations in the cornbelt region.

4. “Unpriced” Benefits Not Yet Reflected in the Economic Calculations

While this economic analysis focuses on measurable costs and grain yield revenue, perennial groundcovers may provide additional forms of value that are not yet priced into the system. These include: soil protection during heavy rainfall and erosion-prone seasons, potential soil health improvements after multiple years of continuous groundcover, improved water infiltration and trafficability, especially in wet springs, weed suppression, which may reduce herbicide costs over time, opportunities for early winter and spring grazing in mixed crop–livestock systems, or improved eligibility for conservation programs (e.g., CSP, EQIP). These benefits did not appear in the first two years of soil data but often require multi-year timeframes to emerge. Future research is needed to quantify whether these long-term ecological and management advantages can offset early yield penalties.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Outreach for this project focused on sharing perennial groundcover concepts, early on-farm results, and practical management lessons with farmers, students, conservation partners, and agricultural professionals across Nebraska and the broader region. Activities took place each project year and spanned classroom instruction, field days, and conference presentations.

2022: Conference Presentations

Although no field days were conducted in 2022 specifically related to this project, PI Brandon Schlautman delivered two invited conference presentations on perennial cover cropping systems. He presented at the Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) Annual Conference and at the Regen Organic Summit, introducing perennial living cover concepts, establishment approaches, and potential agronomic benefits to audiences that included farmers, agronomists, and researchers.

2023: Professional Outreach and Academic Instruction

In 2023, PI Schlautman presented perennial groundcover research and soil health concepts at the Nebraska Environmental Health Association meeting, connecting this work with professionals focused on water quality, environmental monitoring, and conservation.

During the same year, Schlautman also served as a guest lecturer in undergraduate agronomy courses at Kansas State University, providing students with an overview of perennial groundcovers, their ecological rationale, and early agronomic results from the project. These guest lectures helped introduce the system to the next generation of agronomists and agricultural professionals.

2024: On-Farm Field Days and Student Engagement

In April 2024, the project hosted a spring on-farm field day at cooperator Marc Peters’ site near Hampton, Nebraska. Participants viewed first-year KBG groundcover stands, observed strip-till management, and discussed early-season suppression strategies. Approximately six farmers and ten agricultural professionals attended, including representatives from The Nature Conservancy, Nebraska Natural Resources Districts (NRDs), Pheasants Forever, and Central Valley Ag (CVA).

In addition, PI Schlautman again served as a guest lecturer in Kansas State University agronomy courses and began hosting the University of Nebraska–Lincoln (UNL) undergraduate agronomy class at the on-farm research location. Students received hands-on exposure to the perennial groundcover trial, discussing establishment challenges, herbicide considerations, and soil health concepts.

2025: Expanded Field Days and Continued Student Education

In both spring 2025 and summer 2025, the project team hosted additional field days at the Nebraska on-farm location. These events provided opportunities to observe the perennial groundcover system during its second full year of growth, including mature sod development, spring suppression outcomes, and soybean planting into the system. Attendees included farmers, NRD staff, extension personnel, conservation groups, and crop consultants.

PI Schlautman also again hosted the UNL undergraduate agronomy class at the trial site, allowing students to compare second-year KBG performance with earlier establishment years. These visits emphasized real-world agronomic trade-offs, the importance of timing, and the long-term questions surrounding perennial living cover adoption.

Learning Outcomes

Improved understanding of perennial groundcover establishment requirements: Farmers reported better awareness of how timing, seeding method, and early-season management influence the success or failure of establishing Kentucky bluegrass and other perennial groundcovers in corn/soybean systems.

Enhanced knowledge of herbicide compatibility and management constraints: Field days helped farmers understand which chemistries are compatible with perennial groundcovers, how herbicide programs must be adapted, and which weed-management risks must be mitigated when living groundcovers are present.

Stronger understanding of risks and mitigation strategies: Farmers expanded their understanding of risks such as early-season competition, weed escape pressure, or herbicide limitations, and learned specific strategies to reduce these risks during perennial groundcover system adoption.

Increased appreciation for the compatibility of grass-based groundcovers with common herbicide programs: Farmers reported learning that Kentucky bluegrass—a grass species—can be suppressed effectively using Liberty without harming the perennial stand, while still allowing the use of broadleaf herbicides in the cash crop. This compatibility was seen as a major practical advantage over clover-based systems.

Project Outcomes

Economic Sustainability

Economically, this project generated observations and estimates on the costs, yield impacts, and long-term potential of Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) as a perennial groundcover in corn-soy rotations in Nebraska. Although KBG reduced corn and soybean yields by approximately 7%, the system showed promising long-term economic characteristics. Because KBG is rhizomatous and persistent, it is likely to last six or more years without replanting, making its establishment costs substantially lower than annual cover crops like rye across longer time horizons. The project also suggested ways that improved management, especially earlier spring suppression, refined strip-till timing, and optimized fertility placement, may reduce early yield drag and make the system more economically competitive. These innovations are similar to the management practices that needed to be developed for annual cover crops like rye, vetch, and etc. for them to be competitive on a yield basis with conventional (no-cover) systems in the corn belt. Importantly, the project also helped farmers understand the cost structures and risks of clover-based systems compared to grass-based PGC systems, including herbicide restrictions and weed challenges, enabling them to make more informed decisions before investing in these alternatives.

Environmental Sustainability

Perennial groundcover systems have potential to improve environmental sustainability, even though some soil health indicators had not yet shifted after only two years. The continuous living root system created by Kentucky bluegrass protects soil from erosion during the fall, winter, and early spring - periods when Nebraska croplands are highly vulnerable. By maintaining year-round groundcover, the system can reduce sediment loss, improve water infiltration, and help keep nutrients in the field.

Although measurable changes in soil carbon, aggregate stability, and microbial activity were not yet detectable, early numerical trends toward higher microaggregate stability and slightly higher soil organic matter in KBG strips are consistent with the kinds of improvements that emerge only after multiple years of continuous cover. Additionally, perennial groundcovers may reduce the need for soil-disturbing tillage and provide habitat benefits for beneficial insects and soil organisms. The system also aligns with watershed-scale goals of reducing nitrate leaching and improving water quality, which is of high interest to NRDs, conservation groups, and state agencies.

Social and Community Benefits

Socially, the project has increased farmer awareness, curiosity, and technical understanding of perennial groundcover systems. Through field days, undergraduate class visits, presentations, and direct on-farm observations, farmers and students developed practical understanding about the known challenges and best management practices to succeed in trialing perennial groundcover systems.

The work has helped build a learning community around perennial groundcover systems in Nebraska. Farmers expressed increased confidence in experimenting with small strips on their own operations, and conservation professionals reported greater ability to advise producers on risks and opportunities. Undergraduate agronomy students from K-State and UNL gained hands-on exposure to perennial cropping systems that are likely to become more important under future climate and water constraints. The project also engaged organizations such as The Nature Conservancy, NRDs, Pheasants Forever, and CVA, strengthening cross-sector relationships and helping integrate perennial groundcover concepts into broader soil and water conservation initiatives.

A mixed crop–livestock farmer from south-central Nebraska attended our perennial groundcover field day near Hampton in spring 2024. At the time, he was mainly interested in whether the system could solve a practical problem on his operation: finding high-quality early spring forage close to his working facilities so he could keep replacement heifers nearby during artificial insemination (AI). After returning to the 2025 spring field day and seeing a more mature Kentucky bluegrass stand, he decided to try the system and planted some perennial groundcover on one field located near his handling facilities in fall 2025. His plan is to graze the bluegrass lightly in early spring while AI’ing heifers, then suppress the groundcover, strip-till, and plant corn in late May. Because this field serves a specific purpose by providing short-term forage exactly when he needs animals close to home, he noted that a modest corn yield reduction would be acceptable.

For this producer, the value of perennial groundcover was not farm-wide adoption but a targeted use case that offered labor savings, better cattle handling logistics, and an additional quality forage source while still allowing the field to remain in crop production. This example reflects how farmers can integrate perennial groundcover into their operations when the system meets a clearly defined need.

This project generated important early insights into the feasibility of perennial groundcovers in corn and soybean systems, but it also highlighted several areas where additional research is needed before the system can be broadly adopted. Key recommendations include:

-

Evaluate fall establishment timing and methods: The timing of Kentucky bluegrass seeding appears critical. Research comparing early vs. late fall no-till drilling after soybean harvest, and evaluating soil moisture and residue effects, would help clarify when and where the species can establish reliably.

-

Compare Kentucky bluegrass varieties or germplasm sources: Very little is known about whether certain KBG varieties are better suited for perennial groundcover systems. Screening for traits such as aggressive rhizome spread, winter survival, spring regrowth timing, and competition with annual row crops would provide valuable guidance.

-

Expand suppression strategies beyond a single Liberty application: The project relied on glufosinate for spring suppression, but questions remain regarding alternative herbicide options, the optimal timing of suppression, and whether multiple suppression passes may be beneficial in Liberty-resistant corn or soybean germplasm. Research should test whether sequential suppression can reduce yield drag without weakening stand persistence.

-

Identify crop hybrids or varieties with better tolerance to early-season competition: Some corn hybrids may be less sensitive to vegetative competition or early-season shading. Screening commercially available hybrids—and eventually selecting or breeding for compatibility—could reduce yield loss in perennial groundcover systems.

-

Assess performance under irrigated vs. dryland conditions: This project took place primarily on irrigated ground. Trials under dryland conditions are needed to determine whether water competition becomes more limiting and whether management strategies must differ across moisture regimes.

-

Refine nutrient management recommendations: Perennial sods may alter nitrogen dynamics, root-zone distribution, and early-season nutrient availability. More work is needed to understand placement, timing, and rate of fertility inputs in perennial groundcover systems, including whether starter fertilizers or banded applications provide a measurable benefit.