Final report for ONE14-205

Project Information

Without a structured approach to planning and decision making, farm management can become hasty, haphazard and arbitrary. Indeed, in many cases of farm closure, farmers blame the multifarious and interrelated complexities of farming, rather than single dilemmas with clear solutions, for their challenges. Our team of farmers from Essex and Clinton Counties in northern New York, and professors and students from SUNY Plattsburgh, is addressing this challenge by identifying best practices in agricultural decision making and developing workshops that will help farmers adopt these techniques. The trainings we are creating are intended to provide participants the opportunity to LEARN, PRACTICE, APPLY and INSTITUTIONALIZE Structured Decision Making (SDM), a planning approach that offers a standardized and effective method for making complex choices regarding farm management.

Preliminary findings suggest that growers rely on numerous decision-making strategies that range from “gut feeling” to extensive economic modeling. Respondents also identify a few common and regularly occurring decisions that present particular challenges. We call these decisions “cow-pies-in-the-field” because they have the tendency to foul what farmers perceive as ordinary and smooth operating procedures. Among the cow-pies-in-the-field are decisions about hiring and communicating with temporary employees, purchasing new equipment, and completing office work, for example. Additionally, while all respondents emphasize that their farms face great challenges, most report that they are meeting their economic, environmental and social goals. This suggests a difference between the aspirations held by new, direct-market farmers and the conventional measures of farm success used by the established agricultural institution.

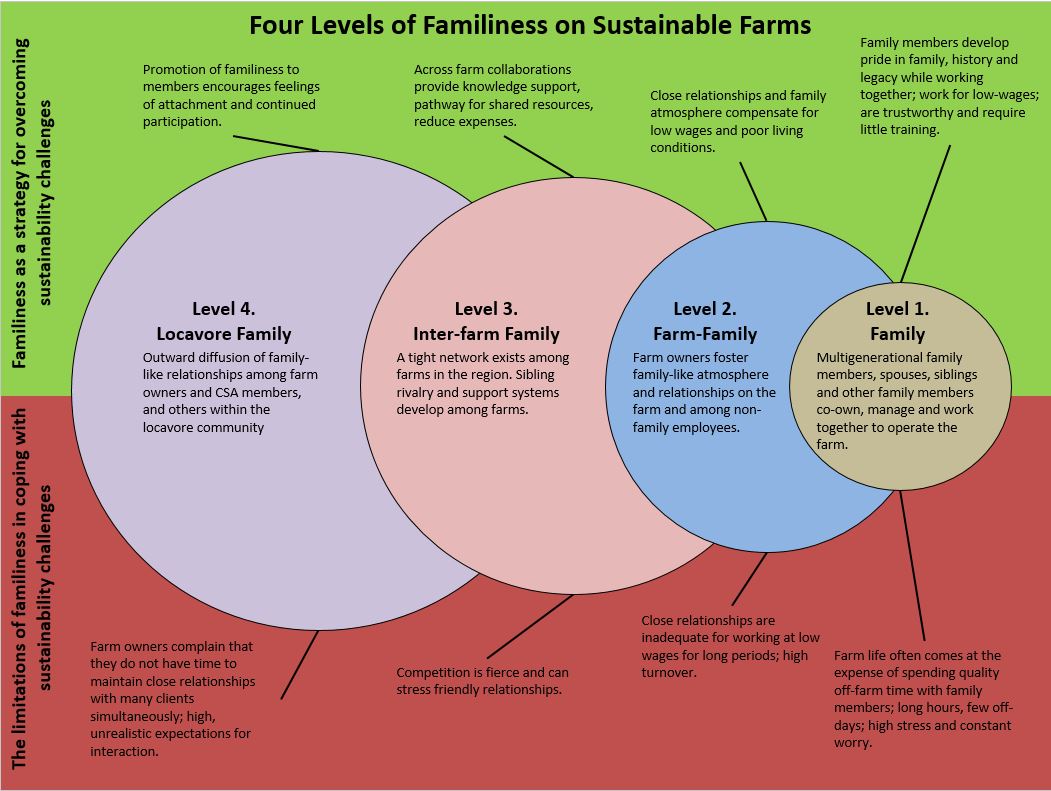

An interesting finding was that farmers who had strong family ties and created family-like ties with employees and customers felt this was significantly related to their success in their business, environment, and social goals.

Farmers reported learning these lessons from SDM training:

1) They acknowledge a more robust consideration of a wide range of values. Many farmers stated that prior to the SDM workshops they only considered a limited range of values– those that they assumed were the “right” ones to consider– without taking time to question these assumptions. In practice this meant reducing decisions to cost/benefit analysis, when in reality the economics of a decision may not be the single driving factor of decision making.

2) They reported limited development and creativity in shaping management alternatives in decisions, limiting the range of alternatives that might be used to manage a particular problem to a few typical strategies. Farmers reported that setting time aside to generate alternatives, and allowing space to generate and consider creative and novel approaches, allows for new management possibilities beyond those typically considered. As a result, even if these choices are not implemented, they often result in adapting more typical approaches to increase success, and enhanced confidence in actions that are selected.

3) Found useful tools for consequence analysis. Our SDM workshops focused on several tools for evaluating the consequences of decisions, which allow farmers to see how various strategies influence their performance measures. Often farmers make judgments based on assumptions. Consequence analysis provides tools for reducing biases and uncertainty.

Introduction:

Our work builds on that of Robin Gregory, Lee Failing, Michael Harstone and others who developed the Structured Decision Making approach typically used by conservation biologists working to protect threatened and endangered species. We built on the SDM model, and adapted it for on-farm decision making applications. We know of no one else adapting SDM to agricultural contexts.

Structured Decision Making is different from many other decision making models because it acknowledges that decision makers are not entirely rational beings. That is, decision makers have values and biases that inform their interpretation of data and inform their preferences. SDM does not seek to set these biases aside, but rather helps decision makers render them explicit and incorporate them into the decision making process so that they do not haunt the decision maker from the shadows. Without acknowledging these biases and values, decision makers often second guess their choices, bias performance measures and interfere with progress and successes in conscious and subconscious ways.

The steps of SDM are: 1) identify problem; 2) collect information; 3) develop objectives; 4) construct performance measures; 5) research and develop alternatives; 6) consequence analysis; 7) alternative selection; 8) implementation; 9) monitoring and evaluation.

Our team believes that this is especially true of small-scale, sustainability-oriented farmers. Farmers that fit this description often have numerous, and sometimes confounding, values and goals. For example, many farmers in this study expressed an interest in economic sustainability- but they do not share the overarching economic motive that often drives corporations with nameless absentee investors. Additionally, these farmers voiced values related to family participation in farm work, desires to continue farming beyond typical retirement age, heightened safety and health concerns, love for the natural world and biodiversity, reduction in carbon footprint and climate change as driving values in farm work. Therefore, we believe that the SDM approach can be of great value to these farmers because it provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating these values along side those more commonly considered in business planning.

Our team is comprised of two faculty members from SUNY Plattsburgh one collaborating farmer and three SUNY Plattsburgh students. University faculty are Curt Gervich in the Center for Earth and Environmental Science and Rich Gottschall in the School for Business and Economics. Our collaborating farmer is Marco Turco, a leader in the local agricultural community and owner of Manzini Farms (and adjunct faculty at SUNY Plattsburgh). Three outstanding students worked closely on this project at various points. SUNY Plattsburgh undergraduate students, Amelia Flanery and Lucas Haight, conducted most of the first and second round interviews with participating farmers. Jessica Draper, a Professional Science Masters Degree student at SUNY Plattsburgh, contributed to development of an in-depth case study of Full and By Farm in Essex, County NY.

The two-phased interviews and workshops I, II and III were the centerpieces of our plan, as they represented key events for data collection, team learning and knowledge dissemination.

We conducted two interviews each with fifteen farmers throughout 2014-2015.Our interviews addressed the following questions: 1) What was the first major decision you made as you launched your farm? 2) What is the most challenging decision you have made while operating your farm? 3) What is a current decision with which you are wrestling? We then asked follow-up questions to fully understand farmers’ decision making processes and outcomes. Through this data collection and subsequent analysis we are constructing a theory of on-farm decision making, a typology of choice types, and successful tools and tactics that farmers use to make decisions. We used this knowledge to inform the development of our workshops and research products.

Our team spent considerable time transforming the data collected and knowledge gained through interviews into our workshops. Each workshop was approximately 3hrs long. Each participant was asked to come with a specific management decision or challenge in mind, along with any supporting documentation that might inform the decision process. The workshop format then introduced the nine step structured decision making process, and assisted farmers to move through this process while focusing on a specific and troublesome decision. Common decisions concerned farm expansion, purchasing of new equipment, hiring of additional employees, and farm succession.

We held our first workshop in February, 2014 and received positive feedback from the eight farmers that attended. The second workshop was hosted by CISA in Springfield, Massachusetts. Approximately 22 farmers, representing 12 different farms, attended. Our final workshop occurred January 18, 2017 and was be hosted by the Essex Farm Institute. Seven farms attended.

We identified the following metrics in our proposal and provide an update on each:

Metric 1: Workshop Attendance. Target: 20 Farmers from Essex and Clinton Counties attend workshops. In total, 38 farmers attended our three workshops.

Metric 2: Ongoing support through summer, 2014. Target: Two visits per farm (40 visits). We conducted two formal interviews with fifteen farms and had dozens of additional informal interactions at farmers markets, local food expositions and other events., including field trips associated with SUNY Plattsburgh sourses. We anticipate a third visit to each farm as we complete revisions to our research papers.

Metric 3: Participant satisfaction with workshops and support. Target: 90% satisfaction rate on evaluations at workshops. The first workshop was well received, with a 100% satisfaction rate. We did not receive evaluations from CISA. Our final workshop hosted by Essex Farm Institute was well received, and several participating farms requested individual support as follow-up to the event.

Metric 4: Case Study Dissemination. Target: Distribute at least 200 case study packets and give 10 oral presentations to agricultural organizations by summer, 2015. We elected not to pursue this objective, instead focusing on more personal interactions with a smaller set of farms. Additionally, we found that incorporating farm management into SUNY Plattsburgh courses was an effective way to assist our participating farms, as these visits were often brainstorming, relfection and innovation periods. Many student projects resulted from this work, benefiting farms and students alike. Finally, coordinating and hosting the Anthony Flaccavento lecture was an outstanding outreach event.

Metric 5: Media Outreach. Target: At least three media stories (radio, newspaper, magazine or television) by summer, 2015. We did not achieve this metric.

Metric 6: Publication of journal article and conference presentation. Target: One article in relevant journal and one conference presentation by fall, 2015. We provided two conference presentations in 2015: 1) Family Enterprise Research Conference, June 4-7, 2015 at University of Vermont; 2) International Food Studies Conference, Blacksburg Virginia, September 17-20, 2015. We submitted two articles to scholarly publications. Unfortunately both were rejected for publication. We plan to return to the field for further data collection and rewriting these papers for submission to alternative journals. We also have a book chapter proposal completed, and are searching for an appropriate publication outlet.

Cooperators

Research

Summary of Methods

To complete our work we conducted introductory and follow-up interviews with regional farmers throughout 2014-2017 (we received an extension for this project in early 2016). We used the knowledge gained from initial interviews to shape the SDM workshops, conference presentations, research papers and book chapter. Introductory interviews with farmers focused on general farm management as well as the identification of specific on-farm challenges and decisions that farmers face. Follow-up interviews focused on the details of each farmer’s decision making processes as they managed the challenges identified in the previous interview. We analyzed data collected during interviews using NVIVO qualitative data analysis software.

Extended Description of Methods

First our team read and discussed several research articles and books on structured decision making. Our discussions were collaborative in nature, often bordering on ideation or design-thinking techniques. During these sessions we discussed ways to innovate typical SDMs procedures to the agricultural context. Our cooperating farmer, Marco Turco, was invaluable in this process, ground truthing our ideas by firmly anchoring our creative process in the day-to-day realities of farming. Gervich and Gottschall have years of research and personal experience in the agricultural and food systems arenas (as long-term customers, farmers' market shoppers, participants in lectures and other events, friends and interested community members), and these experiences provided us with basic knowledge of agricultural and food systems that allowed us to be creative in this space.

With the help of Marco Turco and Cornell Cooperative Extension we identified approximately 25 small-scale sustainable farmers in Clinton and Essex Counties, NY. We reached out to these farmers to inform them about the project and invite them to participate. Many farms expressed interest, and 15 followed through with interviews.

We conducted two interviews each with fifteen farmers throughout 2014-2015. Preliminary semi-structured interviews focused on identifying specific decisions that each respondent felt posed a significant challenge to the farm. Questions asked were:

- What was the first major decision you made as you launched your farm?

- What is the most challenging decision you have made while operating your farm?

- What is a current decision with which you are wrestling?

Second round semi-structured interviews asked participants to drill down more specifically on the decision-making processes used to make choices within each decision. In this case, questions were:

- What about this decision is particularly challenging?

- What resources are you using to assist in this decision?

- What's the first thing (and second, and third...) you did when making this decision?

- Does this process reflect the way you typically make decisions? How is it the same and/or different?

- If this decision is ongoing or you need to make one like it again in the future, what have you learned in the meantime that you would do differently, and what would you do the same?

We then asked follow-up questions to fully understand farmers’ decision making processes and outcomes. Through this data collection and subsequent analysis we are constructing a theory of on-farm decision making, a typology of choice types, and successful tools and tactics that farmers use to make decisions. We used this knowledge to inform the development of our workshops and research products.

The interview protocols are found here:

NESARE-Farm-Decision-Interview-Round-1

NESARE-Farm-Decision-Interview-Round-2

Undergraduate independent research students analyzed the data using NVIVO qualitative analysis software. With the help of our faculty team they coded each interview into thematic codes, then looked for commonalities and anomalies across these themes.

Focusing specifically on the themes related to decision making processes, we extracted decision making practices that farmers felt were particularly successful and unsuccessful, and related them to parallel steps in the SDM process. The steps of SDM are:

- 1) identify problem;

- 2) collect information;

- 3) develop objectives;

- 4) construct performance measures;

- 5) research and develop alternatives;

- 6) consequence analysis;

- 7) alternative selection;

- 8) implementation;

- 9) monitoring and evaluation.

For those practices that showed advantages, we determined where they best aligned with SDM, and developed teaching tools to embed them in our developing workshops. Practices identified as unsuccessful were either left out of the workshop entirely, or included as "lessons learned-- what not to do."

Next we created an outline for our workshop, corresponding powerpoint slides, and a series of graphic organizer worksheets to assist participants think about, write and develop an SDM-based strategy for coming to conclusion on decisions.

Our team spent considerable time transforming the data collected and knowledge gained through interviews into our workshops. Each workshop was approximately 3hrs long. Each participant was asked to come with a specific management decision or challenge in mind, along with any supporting documentation that might inform the decision process. The workshop format then introduced the nine step structured decision making process, and assisted farmers to move through this process while focusing on a specific and troublesome decision. Common decisions concerned farm expansion, purchasing of new equipment, hiring of additional employees, and farm succession.

We held our first workshop in February, 2014 and received positive feedback from the eight farmers that attended. The second workshop was hosted by CISA in Springfield, Massachusetts. Approximately 22 farmers, representing 12 different farms, attended. Our final workshop occurred January 18, 2017 and was be hosted by the Essex Farm Institute. Seven farms attended.

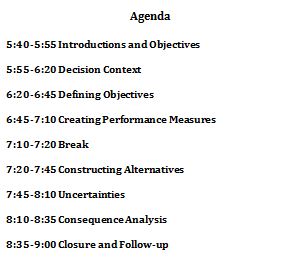

An example agenda for the workshop can be found here:

Graphic organizers for the workshop are found here:

The presentation used at the workshops can be found here:

We partnered with regional agricultural-based organizations, CISA and EFI, to host our workshops. These organizations identified interested farmers from their membership lists, distributed invitations, organized logistics, and facilitated workshop events. Over the course of the project we learned that having a local organization with a membership of farmers to invite was a much more successful way to host events than our research team attempting to coordinate the workshops. Groups like CISA and EFI serve as hubs in the local agriculture and food-systems networks, which makes them trusted sources of information. Put simply- they are known, trusted organizations with strong reputations and our research team is not. When these groups put out calls and invitations for events farmers will show up. When our unknown group makes this attempt, farmers will not.

With our initial NeSARE grant funding we hosted three decision support workshops and provided personal decision support training for 38 farmers in the Adirondack region of New York and Birkshire region of western Massachusetts. We provided support through three trainings (February, 2014; February, 2016; January, 2017) as well as individual farm visits to a small number of participants.

Several of the farms included in the project hosted management-focused field trips for SUNY Plattsburgh students in various courses, and have served as the focus for numerous class projects. Finally, as a direct result of this work our team was asked to coordinate and facilitate a visit by Anthony Flaccavento of SCALE Inc., in June 2016. Flaccavento's talk was attended by 50+ farmers and residents of Essex County, NY. The presentation focused on rural and agriculturally-focused economic development strategies.

As we held our workshops we further analyzed our data, wrote research papers and book chapters, and submitted these works for publication. Additionally, we collaborated with a small handful of farms to do more in-depth decision consulting on an individual basis. Finally, we responded to additional invitations from EFI to coordinate the Anthony Flaccavento event.

As often occurs with qualitative research, some portions of our work exceeded our expectations, while others did not. Or initial scope of work included development of decision making case studies, which we were unable to complete.

In May, 2016 our team presented some of the results from our research at the Family Enterprise Research Conference in Burlington, Vermont. In September, 2016 we presented at the International Food Studies Conference in Blacksburg, Virginia. Also in 2016 we submitted research papers to two separate journals, but they were not accepted for publication. We are currently revising our papers, returning to the field for more data collection, and reanalyzing our data for submission to new journals in the fall of 2017. We have also drafted a book chapter proposal (an in-depth case study of Full and By Farm) and are searching for an appropriate publication outlet.

Summary of Participating Farms

SDM-and-Familiness-Organization-and-Environment-21

Identifying the Everyday Challenges of On-farm Decision Making: avoiding and managing cow-pies-in-the-field.

The Adirondacks of northern New York are experiencing a rapid increase in sustainability oriented farms that consider environmental and social objectives alongside economic goals. In addition to chemical free growing methods and avoiding the use of mechanized labor, many of these farms distribute their produce through community supported models such as farmers’ markets and memberships. Yet, extension agents and other agricultural professionals in the area question whether these young farms will endure. These leaders argue that the potential of new growers is limited by their inexperience and lack of financial training. Our research team of students, faculty and collaborating farmers seeks to understand the decision-making dynamics at work on small, direct-market farms in the Adirondacks. We also seek to build growers’ capacities at Structured Decision Making (SDM), a planning approach that offers a standardized method for making complex choices. Through interviews, participant observation and workshops we are developing case studies of critical decision-making incidents on 13 local farms as well as working with farmers to integrate SDM into their management practices. Our research objectives include identifying the types of choices involved in on-farm decision making; categorizing the tools and tactics farmers use to make decisions; and, assessing the effectiveness of producers’ decision-making strategies. Preliminary findings suggest that growers rely on numerous decision-making strategies that range from “gut feeling” to extensive economic modeling. Respondents also identify a few common and regularly occurring decisions that present particular challenges. We call these decisions “cow-pies-in-the-field” because they have the tendency to foul what farmers perceive as ordinary and smooth operating procedures. Among the cow-pies-in-the-field are decisions about hiring and communicating with temporary employees, purchasing new equipment, and completing office work, for example.

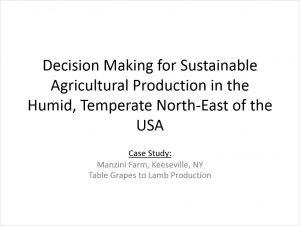

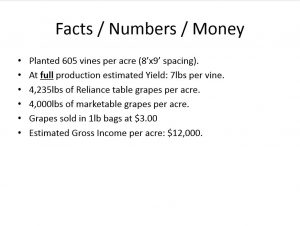

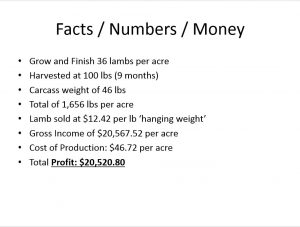

Decision Making Case Study: Manzini Farm

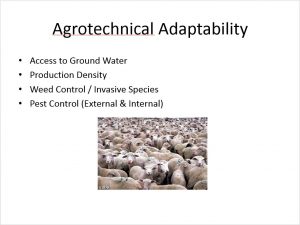

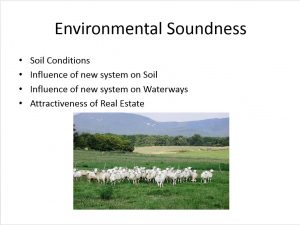

We developed a case study of Manzini Farm, as they reflected on whether to convert (and ultimately did) their farm from growing table grapes to sheep and lamb production. The following images from a powerpoint presentation describe the experience and indicators Manzini Farm used as that made this decision.

A the end of the decision making process Manzini Farm did convert their table grape operation to lamb and sheep. The farm's operators believe this decision aligned with their core values. Ultimately the farm underwent another major shift, and now raises beef cattle. Perhaps Manzini Farm's greatest strength is its ability to adapt and reinvent itself as market forces, interests, resources and environmental assets shift. The following image presents conclusions from this case study.

Farmers' Self-Assessment of Sustainability Goal Attainment

Additionally, while all respondents emphasize that their farms face great challenges, most report that they are meeting their economic, environmental and social goals. This suggests a difference between the aspirations held by new, direct-market farmers and the conventional measures of farm success used by the established agricultural institution. (click on table below to enlarge)

SDM-and-Familiness-Organization-and-Environment-22

As our research evolved we came to see the value of family, both in a conventional and unconventional sense, as critical in on-farm decision making.

The market for locally grown, sustainably produced agriculture may be best described as a movement as so much of the activity is driven by what might be considered extra-market considerations. In spite of the dynamic growth in demand for organic and locally produced food, the market remains miniscule and the viability of these activities remains an open question, especially in communities like the economically challenged areas of Northern NY. There are a small number of consumers who are willing to pay extra for food that is locally and sustainably grown. The scale of production and lack of access to efficient distribution, not to mention the more labor intensive farming methods required to eliminate inorganic inputs increases production costs for benefits that do not include increased caloric production. Thus consumers pay a premium for benefits that are not directly related to meeting their basic food requirements, but more for long term health benefits, concern for the environment, and/or interests in supporting local economy. Furthermore, there are limited numbers of individuals in this market. Thus the local, sustainable food producer is serving a niche market and competing against huge industrial interests. These markets are extremely susceptible to hostile market forces, like a seed that sprouts too in the early Spring.

The involvement of family members in decision making processes was an influential factor in decision making in the local, sustainable farms. In fact, all fifteen of the farms had some degree of family involvement. Primarily, spouses and siblings were working together. While some farms were second or later generation, there were few that had multiple generations working together at the time of this research. Working where you live may enable greater familial interaction and involvement in decisions where work and home life seem to overlap. This activity seems to be more than just an economic activity, but a movement and lifestyle choice which more readily bleeds over into other aspects of life. Family involvement in decision making was a palpable force in these family farms.

Small scale sustainable agriculture is a labor intensive activity and most of the farms are dependent upon non-family, paid employees. Perhaps because of the economic challenges in this fledgling market activity, wages for farm employees are quite low. Compensation is designed around seasonal work rather than hourly wages, and includes farm-produced meals and living quarters for the most valued employees. While these may seem like innovative or alternative economic devices for compensation, there is also a communal aspect to living, eating, and working together that mirrors family life. The creation of a family environment is part of creating a labor force that adapts to the constant changes and challenges that the farmers face. The relationships are seasonal, intense, and often not multi-year. The transience of the non-family workforce is offset by an intense interpersonal relationship that is formed but difficult to maintain through the winters. The following quote offers one example of family-like relationships embedded in farm staff interactions:

Sweet Sage Newsletter: "Jim opened up and Bill opened up and next thing they knew they were both bickering like young siblings (that is how Jim and Bill show affection). ...working side by side every day allowed the duo to understand each other quickly, and turn co-workers into friends."

Marketing is a challenge for these small scale farming operations. Through the collective groups like Adirondack harvest, they are able to promote themselves. Access to local farmers markets and a farmers market association that typically operate only once per week provide distribution. Farmers markets and organizations that provide support to local farms play an important role i creating an inter-farm family among farms in the region. For example:

Sunrise Farm: "We carry (delivery through our CSA home delivery service) our stuff and Cold Creek Creamery's and Sweet Sage Farm's stuff. We'll carry anything that is convenient for us to carry... the customers loved that they could get this variety from all these different farms..."

After that there is an intense effort at personalizing the relationship between farmers and consumers. The farmers are on-site at the farmers markets actively promoting themselves and making personal connections. The weekly newsletter is an important part of bring the consumer deeper into the farming activity- telling plenty of personal stories and weaving and actively weaving together the community that is supporting them. Farmers hold customer appreciation events such as Crowfest and there is always an open invitation for people to come out and visit the farm. As a result of these outreach activities and events strong bonds form between farmers and consumers, and these relationships lead to tangible benefits of support for farmers. For example:

R&B Farm: "Someone gave me $52,000 three years ago for drainage because our fields were wet. They said, "I've never seen the kind of radical transformation you've given our town in terms of what you've done to bring youth, and energy and vitality back to a place that had none."

The local farms we visited in Northern NY were accutely aware of their economic, environmental, and social pressures. The activity of sustainable agriculture is at once an activity that seeks to find a better balance between economic, environmental, and social objectives - their tentative toe hold in the market is explicitly based on their promise to provide balance. For these farms it’s not a choice; they cannot ignore any of these forces. Caught in this very delicate balancing act of their own choosing, they are seeking out like minded individuals who share similar values. In short, this is an activity that cannot be done alone. We found that family members were actively involved, helping with labors and decision making. We found that non-family employees were brought into the activity and treated like family for the duration of their involvement, a short-term and intense familial type relationship with much shared decision making, autonomy for employees, respect for development, and tensions that come with heightened passions around the ideals of this activity. Furthermore, the farms were active in creating a familial connection with their consumers, reaching out to consumers and going past their food needs to nourish their feelings of involvement in this local sustainable movement.

The following image provides a model of the roles family members and family-like relationships play in on-farm decision making among the farms engaged in this research:

Our research resulted in presentations at two national conferences.

The following slideshow was provided at the International Food Studies Conference in Blacksburg Virginia in 2015.

Additional conclusions are documented in the following research article, which our team submitted to Organization and Environment in 2015. The paper was rejected for publication and we received strong suggestions for revision. We are currently in the process of revising the paper and hope to submit another attempt to a different journal in 2018.

SDM-and-Familiness-Organization-and-Environment

Accomplishments

October 2013-January 2014*: Plan Workshop I (reserve space for workshop; develop training materials; outreach/invitations to Clinton and Essex County farmers). Contact media. Accomplished as expected.

January 2014*: Workshop I- introduce and provide training in SDM. Participants identify personal on-farm management challenge and apply SDM to this issue. Workshop includes peer-to-peer support, trainer presentations, panel discussion and other activities. Train farmers in specific decision making tools and techniques. Workshop evaluation. Accomplished as expected. Workshop was held in February, 2014.

February 2014: Workshop I debrief (evaluation analysis; follow-up report writing). Accomplished as expected.

February-September 2014: Ongoing individual SDM support and training; visit each participant at least twice; all participants invited to site visits. Research interviews in conjunction with site visits or via telephone. Accomplished as expected.

August-October 2014: Workshop II planning (reserve space for workshop; develop training materials; outreach/invitations to participants). Analyze/integrate research data. Contact media. Accomplished as expected. Partnered with CISA to complete this activity over winter, 2015-2016.

October 2014: Workshop II- reflect on SDM process and application to on-farm management problems; Identify strengths and weaknesses of SDM and specific decision making techniques; list lessons learned and modification of approach to farming context; identify success stories for use in case studies; ongoing individual SDM support and training. Workshop evaluation. Accomplished as expected. Completed this activity in February, 2016 in collaboration with CISA.

November 2014: Workshop II debrief (evaluation analysis; follow-up report writing). Accomplished as expected in March, 2016.

November 2014-January 2015: Workshop III planning (reserve space for workshop; develop training materials; outreach/invitations to participants). Ongoing individual SDM support and training. Contact media. Accomplished as expected in collaboration with Essex Farm Institute.

January 2015: Workshop III- Apply SDM to 2015 season planning. Participants aim to apply SDM to all major management decisions regarding 2015 season. Workshop evaluation. Accomplished as expected. Workshop held January 18, 2017.

December 2014-January 2015: Case study development and distribution; Workshop III debrief (evaluation analysis; follow-up report writing). Accomplished as expected.

January-September 2015: Write and publish research paper. Continue case study distribution and provide oral presentations to agricultural research organizations and community. Attend conferences. Accomplished as expected. We provided two conference presentations in 2016 and submitted two papers for peer review. These papers were rejected. We plan to submit to alternative journals.

2014-2017 Academic Years: Participating farms hosted numerous field trips for SUNY Plattsburgh courses in Environmental Management, Sustainability, and Environment and Society. Approximately 120 students participated in these experiences. Several class projects and assignments were developed from these trips.

2015-2017: Individual decision support to farms. Full and By Farm Case Study. Over the course of this period we spent approximately 60 hours consulting at Full and By Farm. This work has directly impacted farm planning at the farm in tangible ways. Additionally, we have co-written a book chapter proposal with the farmers and are searching for appropriate publication outlets.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Our team conducted three workshops on structured decision making in collaboration with the Essex Farm Institute in Essex County, NY and Community Investment in Sustainable Agriculture in Springfield, MA.

For the past year we have consulted wit Full and By Farm on a number of issues, applying the SDM process.

Three different farms have hosted field trips for SUNY Plattsburgh students in Environmental Management and Environment and Society courses. Participating farms are Full and By Farm, Whalonsburg, NY; Fledging Crow Farm, Keeseville, NY; and Shady Grove Farm, Schuyler Falls, NY.

We have provided two conference presentations at academic conferences: International Food Studies conference, 2016; Family Business Enterprise conference, 2016.

Learning Outcomes

Participants in the SDM workshops reported a stronger appreciation for robust, data driven and values-based deliberation in decision making. Farmers reported three primary areas of the SDM process that were especially helpful:

1) more robust consideration of a wide range of values. Many farmers stated that prior to the SDM workshops they only considered a limited range of values-- those that they assumed were the "right" ones to consider-- without taking time to question these assumptions. In practice this meant reducing decisions to cost/benefit analysis, when in reality the economics of a decision may not be the single driving factor of decision making.

2) Farmers reported limited development and creativity in shaping management alternatives in decisions, limiting the range of alternatives that might be used to manage a particular problem to a few typical strategies. Farmers reported that setting time aside to generate alternatives, and allowing space to generate and consider creative and novel approaches, allows for new management possibilities beyond those typically considered. As a result, even if these choices are not implemented, they often result in adapting more typical approaches to increase success, and enhanced confidence in actions that are selected.

3) tools for consequence analysis. Our SDM workshops focused on several tools for evaluating the consequences of decisions, which allow farmers to see how various strategies influence their performance measures. Often farmers make judgments based on assumptions. Consequence analysis provides tools for reducing biases and uncertainty.

Project Outcomes

Impacts

We do not have data on the number of farms implementing SDM after our workshops.

One farm has participated in ongoing consulting, and is benefiting from the SDM process. Our team has been consulting with Full and By for 18 months. In that time the farm has moved from considering farm closure as its only viable alternative, to a developing a multi-year management plan that has deepened farmers' commitments to the farm and model. Our team meets weekly with the farm owners. Each week we discuss a focus topic, conduct research, define values and objectives, weigh alternatives against performance measures and advance decisions. These sessions have been powerful and successful.

This project has also had powerful impacts on SUNY Plattsburgh students, who report a stronger appreciation for farmers as "environmental managers" and for local farmers contributions to local economies and environmental success.