Final report for ONE16-283C

Project Information

In this two-year project, we set out to understand nurse cropping (NC) and cover cropping strategies in potato operations to help growers better understand how to protect their soil resources. We found that winter rye or oats planted at 1.2 or 2.5 million seeds/ac effectively protected the soil during the period of planting to emergence. If the NC is incorporated at 21 to 24 days after planting, we found that the cover crop did not affect potato yield or quality, and if the NC were grown up to 30 days, one should likely kill the NC with an herbicide prior to hilling. Prior to this work, using small grains as a NC was unknown to potato growers. Now after field day presentations, magazine articles, website research reports, grower meetings, virtually all 275 Maine growers have been exposed to the practice. At least 15 potato farmers tried this during the project evaluation period, but now almost all of them have actually stopped using it for fear that if it rains and they can't get in and control it, it will hurt yields. I interviewed 14 farmers over the last month for another project, representing about 10,000 acres of potatoes, and i asked them specifically if they were using the technique and they said no. I asked them if they might use it if it was cost shared, and then they said that then they likely would. That is what i am working on now.

We also learned a great deal about undersowing small grains and management of the cover crops. We also found that these practices only protect the soil and do not limit yield or negatively affect potato fertility. Of the 14 growers that i just interviewed, 12 of them undersow their grains with either clover, or italian ryegrass. Five growers, representing approximately 5000 acres, undersow their small grains with annual ryegrass or clover and allow that to rest a third year. A three-year rotation with a year of rest is the goal for soil quality building.

Two presentations were delivered on nurse cropping in potatoes at the NY/NE certified crop adviser training in Syracuse in November 2017, as well as to growers at the NE Fruit and Vegetable conference in Manchester in December and two field day events during the summer. In January 2018, two presentations were made on the use of nurse crops, with two presentations and a farmer panel at a potato conference. A total of 427 farms and 211 agricultural service providers participated in these educational activities, and 20 farmers changed or adopted a practice as a result of this project.

An article on this work was published in the American Journal of Potato Research on the Nurse Crop work.

Goal 1: Assess the capacity of nurse crops to hold N and protect soil from eroding prior to potato hilling.

Objective 1- determine optimum nurse crop species and planting rate to obtain optimum efficiency.

Objective 2- assess optimum method and timing of nurse crop destruction.

Goal 2: Assess the effects of alternative methods to cover cropping and primary tillage timing on small grain yields, potato yields, and production efficiency.

Objective 3- determine most effective and efficient methods for fall cover and primary tillage preceding a potato crop using either underseeding or cover cropping.

Objective 4- assess economic feasibility of cover crop and tillage methods.

Nurse Crop Trials

We will establish nurse crop trials at the two University of Maine Experiment Station farms (Orono, ME and Presque Isle, ME). We will evaluate seeding rate, seed type, and destruction dates and methods of the nurse crop in two replicated trials. Cereal rye and spring oats will be used as the nurse crops with seeding rates of 100 or 200 lbs of rye or oats per acre. Nurse crop destruction methods of herbicide, hilling/cultivation, and herbicide plus hilling will be compared. We will grow round white potatoes at the Orono location and Russet Burbank potatoes for the Aroostook county location. Each of those varieties are typical for the area. Plot areas will be established, seed spread by hand and incorporated with a tine cultivator. Then plots will be marked and hand planted. Seed will be covered with planter discs.

At approximately 21 to 24 days after planting (6”-8” potato plant height), above and below-ground nurse crop biomass will be collected by plot (two 2-ft2 samples per plot) to assess production prior to destruction. A separate strip of plots will be sampled and destroyed at 30 days after planting. We will collect soil samples for nutrient analysis and nurse crop N status will be assessed by NDVI prior to killing, and potato crop N status will be assessed at 4 and 8 weeks after hilling.

Yield samples will be taken a month following top-kill. Potatoes will be graded to US number 1 and total yield. Ten potatoes will be sampled for skin quality and internal defect. Experimental treatments will be replicated five times.

Cover Crop Method and Tillage Timing Trials

We will compare current conventional tillage potato/grain production to a modified version of the research conducted by Griffin et. al., that would include underseeded vs. monocropped small grains. Underseeded (annual ryegrass) plots would include treatments of postharvest tillage (late summer), late fall chemical desiccation, or spring tillage. Monocropped plots would include treatments of fall tillage, fall tillage plus spring oat cover, fall tillage plus cereal rye cover with spring chemical desiccation, or spring tillage of monocrop stubble.

Plots (grain phase) will be established at the Aroostook Experiment Station in spring of 2017. The seven treatments will be organized as a randomized complete block design with four replications. Grain yields and quality parameters will be recorded. Fall and spring ground cover will be recorded preceding the potato phase. Spring ground temperatures and moisture levels will be recorded for individual treatments. Russet Burbank potatoes will be planted in the spring of 2018. Yield and quality parameters will be recorded in the fall at harvest.

Local standard crop care practices (pesticide applications, cultivation) will be conducted by research farm staff.

Comparative cropping budgets will be estimated for each treatment of the cover crop/tillage timing trial to assess the potential return to growers for adoption of a particular practice.

Educational Activities

Twilight Meeting- We propose to conduct a twilight meeting at the Aroostook Experiment Station in which we will send invitations to our grower mailing list (300 potato growers). We will likely look to conduct this in July 2017 and July 2018. We will conduct a presentation on the research, current observations, and provide a brief tour of the plots. We expect 15-20 growers to attend these meetings each year.

Maine Potato Conference- The annual Maine Potato Conference is conducted each January in Caribou, ME. We propose to provide one to two presentations on this research for the 2018 and/or 2019 conferences. Approximately 200 growers, consultants, and university staff and faculty attend each year.

Maine Grain Conference- The Maine Grain conference is conducted annually during the month of March. We propose to provide a presentation at this conference in 2018. Approximately 60-80 growers, consultants, and university staff and faculty attend each year.

Maine Grain and Oilseed Newsletter- We propose to write an article about this research and demonstration that will be disseminated through this newsletter (700+ subscribers including potato mailing list).

The potato production systems in the Northeast are predominantly two-year rotations of potato and small grains (barley, oats, or wheat). With a short growing season, potato production in the Northeast doesn’t provide much opportunity for cover-cropping, with potato harvest occurring during the last half of September through the first half of October. In the grain production phase of the rotation, the practice of post-harvest primary tillage dominates the region in order to provide early preparation and planting of the subsequent potato crop in the spring.

With our current production system there are several points where the risk for soil loss is high. With little crop residue and potentially compacted soils from field traffic, the period after potato harvest is one concern. Another is the late summer/fall tillage of small grain ground eliminating crop stubble or regrowth of underseedings (clover, annual ryegrass). This practice exposes soils to potential erosion and runoff from fall rains and spring snowmelt. Lastly, the time period from potato planting to row-closure is sensitive to erosion and runoff events and has recently gained prominent attention in recent years owing to our increase in early summer high-intensity rain events (> 2” per hour events) causing significant damage to fields and roadsides, and leading to visible water pollution issues.

Recently, planting small grain nurse crops at planting has been explored to provide soil protection and reduce soil loss during the period from potato planting to row closure. This project has been initiated by McCain Foods field staff in conjunction with local on-farm cooperators. Nurse crops can improve rainfall infiltration, the roots hold soil in place, and possibly improve N cycling in the soil system (Hoorman, 2009; Mitchell, 1995). While this type of practice has been used in some vegetable and sugar beet production (LeBlanc, 2014; Fornstrom and Miller, 2008), this practice is new to potatoes. The development of another practice, one-pass hilling, has made this practice economically feasible. While growers are optimistic about nurse cropping to reduce soil loss, McCain agronomists have found mixed results.

Griffin et. al. (2009) conducted research on delaying tillage and the effects of cover cropping in potato systems in Maine (2002-2005). In their research they compared agronomic effects on potatoes and barley of spring tillage vs. fall tillage of small grain (with or without underseeding) ahead of potatoes, and no-tilling of grain into potato crop residue the spring following potato harvest.

To implement this system, one would spread one to two bu/ac of small grain seed across the soil to be planted. Then in the process of planting potatoes, the grain gets incorporated into the soil. It emerges quickly and provides protection from erosion until its time to hill the potatoes. If it is done at 3 weeks, it can be adequately killed by the hilling operation. If it is four weeks out, an herbicide should be used to kill the biomass so that it won't get ahead of the grower.

Despite the success of this conducted research, the practices outlined within it have not been adopted. Working with a small group of potato producers, we have identified some alternative practices to research and demonstrate that could produce a more amenable recommendation to the industry. Of most concern to these producers is sufficient time to plant their potato crop.

Many view the potentially excessive amount of green biomass worked into the soil in the spring to be a detriment that would set back planting times; owing to the time to breakdown the soil-incorporated cover and the potential for slowed drying and warmup of the soil. Tillage of a wet field prior to planting is most problematic at harvest as soil clods decrease harvest efficiency and possibly cause tuber damage (bruising and nicking).

Cooperators

Research

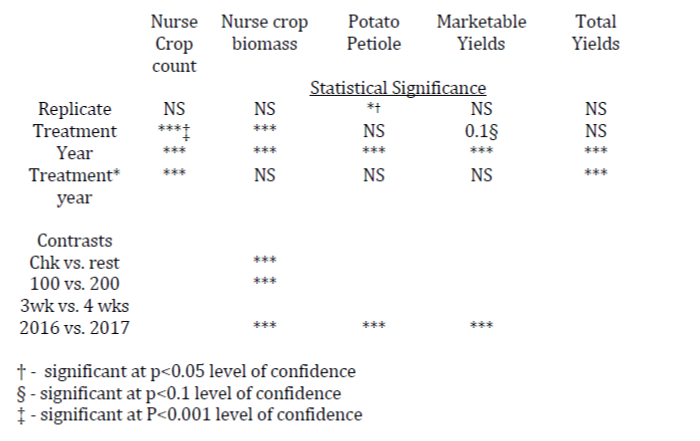

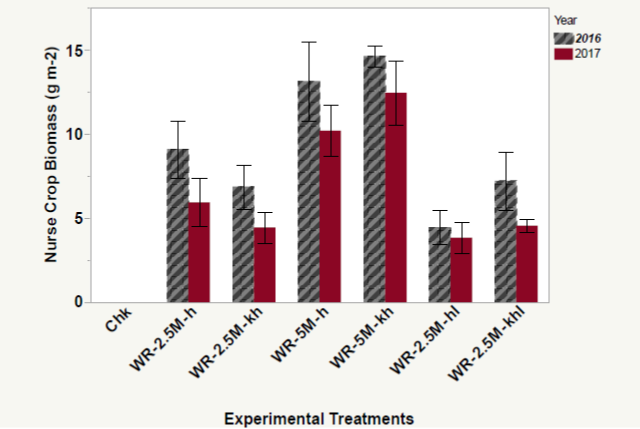

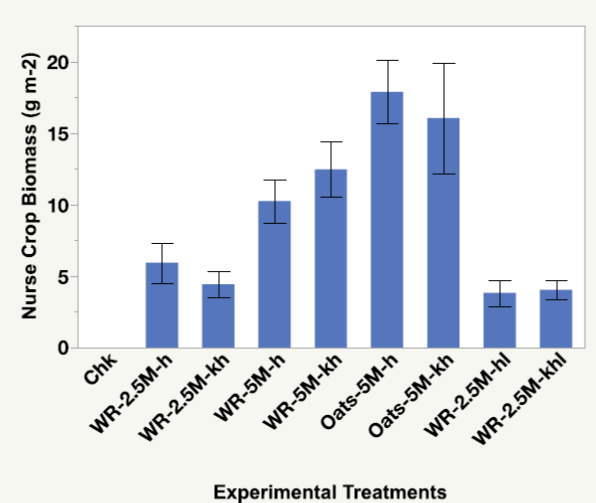

In the summer of 2017, two trials were initiated at each of two locations in Maine (four trials total). Nurse crops and rotation studies were evaluated in Orono and Presque Isle Maine. In the nurse crop trial, the fields were prepared in May. In Orono, fertilizer was banded in the soil as the rows were marked by the planter. Nurse crop treatments were broadcast across the soil surface and a lely cultivator was used to scratch the surface and slightly incorporate seeds. In Presque Isle, nurse crop treatments were broadcast, and seed was planted with a potato planter. Nurse Crop treatments we compared included 100 and 200 lbs seed/ac rates for both cereal rye and oats. Another set of treatments were broadcast at 100 and 200 lbs/ac with these plots being killed with herbicide prior to hilling. Finally we sowed cereal rye at 100 lbs/ac and allowed those treatments to grow an additional week to determine if we could get another week of protection at no cost to the crop.

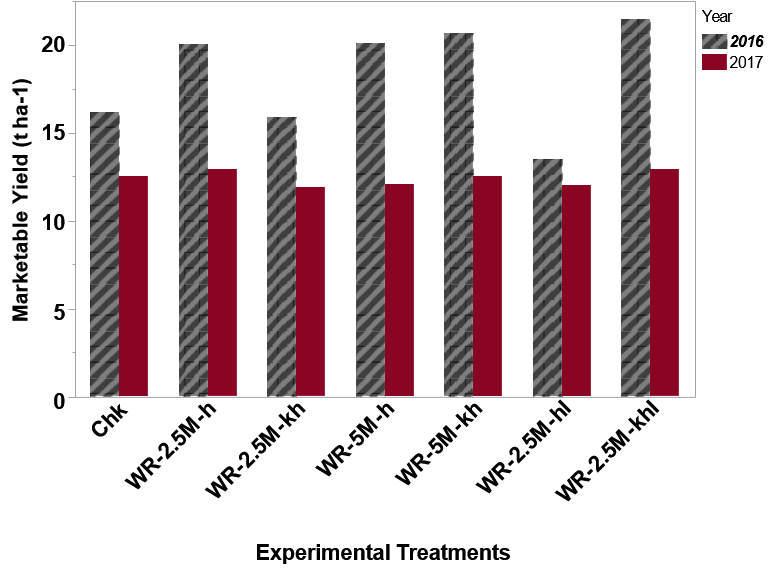

Biomass counts and samples were taken at three and four weeks after planting. Leaf petioles were collected from the 4th leaflet from the top of the plant in July to see if the nurse crop affected yield or potato quality. For yield and quality we sampled 15 feet of row and washed and graded these in storage.

The potato rotation study was started in early May by sowing barley at 1M seeds/ac and undersowing three of the treatments with annual ryegrass. The barley was combined off in early August. One of the undersown plots was disked two days after harvest. The other two annual rye under-sown plots were allowed to grow. Winter rye and oat cover crops were sown at a 150 lb/ac rate. One of the undersown annual rye grass was sprayed with glyphosate at the end of the season. Biomass samples of the actively growing cover crops were made in late November. In 2018, we assessed cover crop biomass yield, and learned that about 40% of the italian ryegrass biomass was still alive and growing. This was disked in and potatoes planted. We took assessments of potato growth and development, and then harvested the potatoes for yield and quality.

I have two years of data collected on nurse cropping from the Orono location, and we completed one study looking at the effect of undersown italian ryegrass on barley yield and its subsequent influence on potato yield. The studies up north failed. There was no effect of italian ryegrass or cover crop on potato growth or yield in 2018. The positive component of this is that the undersown italian ryegrass did not hurt barley yield, and could be managed any way the grower so chose with very little influence on potato yield and quality. In the nurse crop study we found that growers can sow winter rye at 100 to 200 lbs/ac at potato planting and disk it in in three weeks when they do their one-pass hilling. If they wait four weeks (an extra week of protection), they should likely kill that with herbicide to make sure that it won't get ahead of them. The nurse crop did not influence yield or quality in either year in very dry conditions.

the Witter Center Rogers Farm in Stillwater Maine in 2017.

Research conclusions are as follows: Nurse crops can effectively armor the soil from erosion, but they do not affect N fertility, and they do not affect yield. As a result, we have to pitch a practice to growers that will effectively protect their soil but will increase that cost of production. This means growers have to invest to seed down the field and hill it in when they don't see a bottom line yield increase. For farmers with sloping ground, it is a practice that should be employed. Getting farmers fired up to do it without a probability of a yield increase has been a hard sell. I recently interviewed 14 potato farmers for another project, and all of them have given up nurse cropping when the processor decided that they didn't think it helped yield. All 14 growers had heard of it, knew how it would work, but chose not to do it for fear that it would "get away from them" and hurt yield. All of them undersow their small grains now. They have learned from our work that it does not hurt their grain yields and can add cover to their system.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Two presentations were delivered on nurse cropping in potatoes at the NY/NE certified crop adviser training in Syracuse in November 2017. The room was filled with ag educators and consultants. I also presented this to growers at the NE Fruit and Vegetable conference in Manchester in December, at two field day events during the summer.

In January 2018 I gave two presentations on the use of nurse crops. I gave one to 135 potato producers, one to 55 ag service providers, and then we held a farmer panel at the same potato conference and all three producers talked about how Nurse Cropping had positively influenced their production by reducing erosion.

I published an article in the American Journal of Potato Research on the Nurse Crop work.

DOI : 10.1007/s12230-018-9684-7.

Learning Outcomes

Nurse crops and potato rotation studies have been the topic of two Maine Potato Conference presentations. Each year there are approximately 130 to 150 people that attend this conference. After discussing our results (which showed positive results for reducing erosion but no effect on yield or N status in the plant) in the first presentations (2017), last year, in 2018, we had a panel of growers talk about the practices that they felt were influencing their productivity, and each mentioned using Nurse Crops in that work. However, recent interviews have shown that many of those have now stopped using the nurse crops because the processor for which they contract did not find it helped its bottom line (yield), so they are not encouraging that. However all are undersowing their small grains.

Future plans include a presentation on our work on the undersown annual rye grass and cover crop work. With the three different presentations, I will be able to say that approximately 400 farmers better understand nurse crops, why they matter and the importance of how to manage undersown grains or cover crops.

Project Outcomes

The largest success from this project is what I would call the main-streaming of nurse cropping. In 2015 this practice was unknown. In 2019, the Maine Potato Board's research priorities includes developing BMPs for using nurse crops to improve soil conservation, and they have expressed interest in trying to determine if nurse crops can reduce aphid feeding and PVY transmission early in the growing season.

Our growers collectively understand the practice, why one would use it, what the risks are, and that it has little or no influence on plant fertility or N status. I am going to apply for some funds from the Maine Potato Board to develop a Fact Sheet to guide growers decision tree on how to use Nurse Crops.

As the project ended in 2018, I have completed the two year Grain/potato crop cycle and will do programming to show growers what we have learned with that work. Since we did not find how we managed undersown ryegrass to make significant differences on potato yield or quality, growers can use undersown annual rye grass or clover with confidence that it will only help to protect the soils and give growers an opportunity to allow soils to rest with no tillage.

This project yielded good information on how to protect soils in a changing climate/environment. Nurse crops have the opportunity to protect the soil during the three weeks without potato cover. Grower interest in this continues. It was beneficial to have one year of prior data coming into this funded cycle. That allowed me to collect one additional year of data, and then be able to submit a paper for publication. I also had presented that first year's data at our potato growers' meetings, and this helped take the results from this funded work and push them along. As we are just completing the two year cycle of barley followed by potatoes, I really can't speak to how much growers have adopted this because I only presented the results at one field day, and growers haven't had a year or so to let the material percolate in their minds.

We did answer what we set out to learn. We know that nurse cropping potatoes is a solid practice with only a slight impact on growers if they do not get the nurse crop turned under. We have strategies for growers if there are problems. I also think growers will continue to use undersown annual ryegrass or red clover, but I will continue to promote leaving that grass to grow a year and let the soil rest. I am convinced that even though the growers may likely not see a positive yield gain from either of these processes, I do believe that they have recognize the benefits of soil health and that both of these processes will help accomplish that.