Final report for ONE17-292

Project Information

Producers continue to diversify the crops they grow to include cut-flowers and essential oil herbs. Their overarching goal is to strengthen the economic and environmental sustainability of a farm business through diversification. Unpredictable weather extremes, pest challenges, and shifts in consumer demand are forcing farmers in the northeast to explore a wide range of high value crops. Lavender thrives in drought conditions while mint prefers wet soils. These two herbs could offer farmers an “insurance policy” in our changing climate. The idea begin that at least one of these high value oil crops would produce a marketable crop given flood or drought conditions. Collaborating with two farms in eastern NY, this two-year project investigated which varieties of lavender (Lavandula spp.), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and peppermint (Mentha x piperita) are most winter hardy and susceptible to insect and disease pests under organic management. Lavender and mint variety trials were planted in Whitehall and Hoosick Falls, NY in May 2017. Insect and disease pests observed on lavenders included, tarnished plant bug, spittle bug, two-spotted spider mite, Phytophthora nicotianae, Septoria spp., Xanthomonas spp., Pythium spp., and Fusarium spp. Scale insect and powdery mildew were identified on mint cultivars. Considering winter hardiness, oil yield and quality lavender data collected thus far, Folgate, Sashet, and Phenomenal appear to be the best suited essential oil cultivars for our region. Lavender cultivars differed significantly in the oil volume produced and ideal harvest dates. Essential oil compounds found in both lavender and mint cultivars were identified and are discussed.

Outreach to farmers occurred with on-farm workshops and a presentation at the NY Cut Flowers Conference.

Working with two collaborating farms in eastern NY (Lavenlair Farm in Whitehall and Hay Berry Farm in Hoosick

Falls), this project will investigate which varieties of lavender (Lavandula spp.), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and

peppermint (Mentha x piperita) are most winter hardy and susceptible to insect and disease pests under organic

management. Importantly, this project will also evaluate whole bud/leaf and essential oil quality. Herb, flower,

vegetable, berry, and tree fruit producers in addition to stakeholders in culinary and beverage markets will benefit

from this work.

Question: Which commercially available lavender, spearmint, and peppermint varieties grow best in eastern NY?

Objective 1: Determine which lavender varieties survive the winter under 24F degree row cover.

Objective 2: Identify and quantify the major insect and disease pests that attack lavender and mints.

Objective 3: Measure the yield and quality of each essential herb variety against what is found in other regions.

Objective 4: Evaluate essential oil herb quality with the farmers and local stakeholders (tea company, distiller, and

baker).

Food and beverage producers in the northeast are continually adapting to market and climate changes. In some regional locations, farmer’s markets and direct sales have reached a saturation point (SARE ONE16-255). In light of saturation and the need to be ready for flooding one season and extreme drought the next, farmers are searching for ways to increase the diversity of crops they grow for both environmental and economic sustainability. Working with two collaborating farms in eastern NY, this project seeks to investigate which varieties of lavender (Lavandula spp.), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and peppermint (Mentha x piperita) are most winter hardy and susceptible to insect and disease pests. Importantly, this project also evaluated lavender flower and mint leaf essential oil quality.

There is very little research-based material available on herbs grown for essential oil production in the northeast region. Essential oil herb culture has been perfected in the Pacific Northwestern states of Washington and Oregon. As with grains and hops that continue to expand in northeast acreage, research and educational materials created for other regions do not necessarily apply to our climate, production scale, or market. North-central counties of NY produced very high quality Hotchkiss peppermint oil from 1837-1889. Growers in NY produced 44,500 lbs of peppermint oil in 1846. The agronomic and processing knowledge associated with NY peppermint production left the region as verticillium wilt impacted the crop and agriculture moved west (Monje 2005). In 2012, Dr. Curtis Swift investigated which lavender varieties produced the highest essential oil content in Colorado (Swift et al. 2012). This valuable study gives educators and farmers in the northeast quality measures for lavender but we cannot directly apply their findings to our more moist region.

SARE farmer grant FNC10-819 explored the use of high tunnels and soil amendments in Ohio lavender production in hopes of improving winter survival. Peace Tree Farms, PA released a trademarked, cold hardy variety of lavender (‘Phenomenal’) in 2002 which grows well here in the Northeast. In Whitehall, NY, Lavenlair Farm’s first question to me was “Is there an essential oil profile for ‘Phenomenal’ available?” This variety survives their zone 5a winter but to my knowledge there was not an accessible chemical profile until this project. We know that lavender yield and quality are dependent on latitude, soil nutrients, and pest management strategies (Topalov 1962, McGimpsey et al. 1999, Zheljazkov et al. 2012). Valuable research on mints in Finland, indicated that plant spacing, water, and nutrient availability influence mint oil yield and quality (Aflatuni 2005). Drought stress can reduce the quality and yield of mint oil (Nakawuka et al. 2014).

In the Pacific Northwest, Phytophthora on lavender and Verticillium wilt on peppermint remain the biggest pest challenges to western production (Personal communication with Victor’s Lavender, OR and Essex Labs, WA). The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture (OMAFRA) crop profiles are the most regionally relevant agronomic resource on both lavender and mints for commercial producers. The most challenging pests for mint in Ontario currently include verticillium wilt (Verticillium dahlia), rust (Puccinia menthae), and the four-lined plant bug (Poecilocapsus lineatus) while lavender is plagued by Septoria (Septoria lavandulae), Phytophthora (Phytophthora nicotianae), and four-lined plant bug.

Preliminary data collected in 2016, indicated that there were additional insect and disease pests present in lavender grown in eastern NY. Upon further investigation for this project in 2017 and 2018, we have indicated that lavender requires disease management more than insect pest management. Positive identifications of plant diseases including Septoria, Phytophthora, Xanthomonas, and Alternaria have been confirmed on lavender in NY. Overall, root rots and leaf spotting diseases are the most widespread pest problems for lavender in the Northeast. Spittle bugs (Cercopidae spp.), tarnished plant bug (Lygus lineolaris) and two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) have been noted as insect pests of lavender. However, managing the weeds in the your field can reduce many of the insects that damage lavender.

The first year of mint data collection was conducted in 2017 season. Mints are native to stream-bed habitats. Therefore they prefer wet but well-draining soil. In the Pacific Northwest, the major production region of US mint, the crop is grown as a field of mint “hay” where it is overhead irrigated and mechanically harvested.

Literature Cited

Aflatuni 2005. The Yield and Essential Oil Content of Mint (Mentha spp.) in Northern Ostrobothnia. University of Oulu, Department of Biology Dissertation. 1-49.

Christie, M. NESARE Partnership Grant. 2017. Building loyalty: Testing the efficacy of farmer’s market loyalty programs to engage the community and enhance sales. ONE16-255.

Fletcher, R. S., Slimmon, T., and L.S. Kott. 2010. Environmental factors affecting the accumulation of rosmarinic acid in spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) and peppermint (Mentha piperita L.). The Open Agriculture Journal 4: 10-16.

McGimpsey, J.A., and Porter, N.G. 1999. Lavender a growers’ guide for commercial production. Crop and Food Research Mana Kai, Rangahau. New Zealand.

Monje, Scott C. "Peppermint." Encyclopedia of New York State. Ed. Peter R. Eisenstadt and Laura-Eve Moss. Syracuse University Press, 2005. 1192. Academic OneFile. Web. 23 Oct. 2016.

Nakawuka, P., P. Troy, K. Gallardo, D. Toro-Gonzalez, R. Okwany, D. Walsh. 2014. Effect of deficit irrigation on yield, quality, and costs of the production of native spearmint. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering. 140 (5).

Prell, M. North Central SARE Farmer Grant. 2011. Increasing production and oil producers through the use of hoop housing and soil amendments. FNC10-819.

Roberts and Parkinson 2014. A bacterial leaf spot and shoot blight of lavender caused by Xanthomonas hortorum in the UK. British Society for Plant Pathology; New Disease Reports. 30:1

Swift, C. 2012. Research Results and Findings of Lavender Essential Oils Produced by Western Colorado Growers. Lavender Association of Western Colorado, Palisade, CO.

Topalov, V.D. 1962. Lavender. Essential Oil Crops and Medicinal Plants. 15. HR.G. Danov Press, Plovdiv, Bulfaria. 153-183.

Westerveld, S. 2016. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/CropOp/en/herbs/lavender.html

Zheljazkov, V., T. Astatkie, A. Hristov. 2012. Lavender and hyssop productivity, oil content, and bioactivity as a function of harvest time and drying. Industrial Crops and Products. 36: 222-228.

Cooperators

Research

In 2016, we began a preliminary variety trail before this NE SARE grant project began. Eight lavender varieties were planted at Lavenlair Farm in Whitehall, NY. Pest and plant growth measurements were collected. Some of the data collected in this preliminary year are included in this report.

Lavender Variety Trial: Plants and Culture

During the week of May 8, 2017, prior to planting, Lumite black row fabric and irrigation lines were installed. Soil samples were also taken at this time. A total of 13 lavender cultivars were planted on both Hay Berry Farm in Hoosick Falls, NY and Lavenlair Farm in Whitehall, NY from May 17-19, 2017. Twelve English lavender (Lavendula angustifolia) cultivars and 1 hybrid (Lavendula x intermedia) were ordered and planted. Agdia test strips were used to sample 1 plant per variety for phytophthora species upon arrival. Cultivars are listed in table 1. Plugs were purchased from several different companies because they are hard to find from one source (Table 1).

These trials were planted in a randomized complete block design, replicated 5 times. Plants were spaced 3’ apart within the row with 6’ inter rows. Each plant was watered in with 1 liter Rootshield Plus (BioWorks). This wetable powder biofungicide was mixed in a 5 gallon bucket at a rate of 0.4lbs/4 gallons water. Lavender was irrigated as needed throughout the first 4 weeks of establishment. Lavender was not fertilized. Winter survival data was collected on May 29, 2018 which included percent of plant dead and a 0-5 survival rating (0 = dead, 5 = no damage).

Insect and disease scouting began the first week of June and continued until the last week of August in both 2017 and 2018. Three leaves per plant were inspected for pests. Insects were identified in the field and Septoria sp. severity was rated on a scale of (0-5), 0 = not present and 5 = severely infected. Unknown pathogens were photographed, sampled, placed into plastic bags, and mailed to plant pathologist Dr. Margery Daughtrey at the Long Island Research Center (LIHREC).

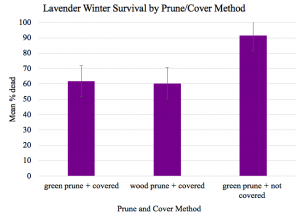

In 2017, lavender buds were hand picked off of plants throughout this first growing season to establish a strong root system. In 2017, lavender was pruned and shaped into a tight ball on September 29th at Hay Berry Farm and on October 12th at Lavenlair Farm, cutting at 2 inches above the woody stem line with scissors. In 2018, lavender was pruned December 6th at Hay Berry and on October 15th at Lavenlair Farm. A preliminary comparison of “green pruning” (cutting 2 inches above the wood line on stems) vs. “wood pruning” (cutting into the wood 2 inches above the soil line) was conducted at Hay Berry Farm in 2018 (Image 2). Steel wire support hoops (Johnny’s 76” #10 gauge) were installed along each lavender row in December after several frosts. Hoops were spaced 6’ apart. White 1.5oz/cuft2 row cover from Gardener’s Supply was draped and secured with 4” staples (Image 3).

|

Lavender Cultivars |

Source |

Species |

|

Betty's Blue |

Joy Creek Nursery |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Fiona English |

Joy Creek Nursery |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Twickle Purple |

Joy Creek Nursery |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Hidcote |

Mountain Valley |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Phenomenal |

Northcreek Nursery |

Lavandula x intermedia |

|

Ellagance Purple |

Silverleaf Greenhouses |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Folgate |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Mailette |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Melissa |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Royal Velvet |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Sashet |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

Buena Vista |

Victor’s Lavender |

Lavandula angustifolia |

|

SuperBlue |

Ricter’s Herbs |

Lavandula angustifolia |

Table 1. Lavender cultivars, sources, and scientific names planted in May 2017.

Peppermint and Spearmint Variety Trial: Plants and Culture

During the week of May 8th, prior to planting, Lumite black row fabric and irrigation lines were installed. Soil samples were also taken at this time. A total of 9 mint cultivars were planted at both Hay Berry Farm in Hoosick Falls, NY and Lavenlair Farm in Whitehall, NY from May 17-19, 2017. Plugs were purchased from several different companies because they are hard to find from one source (Table 2). These trials were planted in a randomized complete block design, replicated 5 times next to the lavender trials. Each 3’x 3’plot contained 8 rhizomatous plants. Plots were spaced 2’ apart within the row with 6’ inter rows. Each plant was watered in and irrigated using drip tape as needed throughout the season. Mint plots were fertilized with a split application of North Country Organcis ProGro (5-3-4) at a rate of 100lbsN/acre. The first application was 2 weeks after planting and the second was in mid-June.

Insect and disease scouting was conducted as described above. Additional data collected included flowering date, stand establishment, and winter survival. Winter survival data was collected on May 29, 2018 which included percent of plant dead, 0-5 survival rating (0 = dead, 5 = no damage). In 2017, mint flowers were pruned off of plants throughout the first growing season to establish a strong root system.

|

Mint Cultivars |

Source |

Common Name |

Species |

|

True peppermint |

Johnny's |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

|

pineapple/apple mint |

Johnny's |

peppermint |

Mentha suaveolens |

|

Double mint |

Johnny's |

spearmint |

Menta spicata |

|

M837 |

Mint Research Council |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

|

Black mitcham |

Mint Research Council |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

|

Murray mitcham |

Mint Research Council |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

|

Native mint |

Mint Research Council |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

|

Scotch spearmint |

Richters |

spearmint |

mentha x gracilis |

|

Chocolate mint |

Richters |

peppermint |

Mentha x piperita |

Table 2. Mint cultivars, sources, and scientific names planted in May 2017.

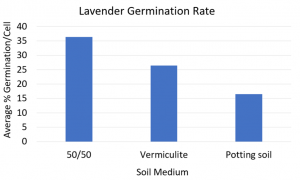

Lavender Seed Germination Study

A preliminary, small-scale lavender seed germination study was conducted in a greenhouse at the Schenectady County Horticultural Education Center (SCHEC). English lavender seed from Fruition Seeds was planted to test which of 3 different soil mediums showed the highest germination rate. One 50 cell tray was planted with 3 seeds/cell on September 8, 2017. Two rows (10 cells) contained SunGro potting soil with mycorrhizae, 2 rows (10 cells) contained Vermiculite, and 2 rows (10 cells) contained a 50/50 mix of potting soil and vermiculite. The tray was watered as needed and was not kept on a heated pad in the greenhouse which was kept at 70F during the day, 50F at night. Germination rate was calculated on October 18th (41 days of growth).

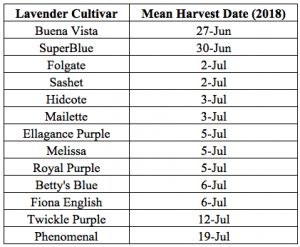

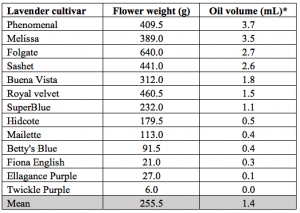

Lavender Harvest

Spikes from these second year lavender plants were harvested for the first time in 2018. When a lavender cultivar had 50-75% of flowers open on each spike, harvest for oil distillation began. Table 3 indicates the mean 2018 harvest dates by lavender cultivar. The 2018 harvest began on June 27th and finished on July 31st. Morning dew can reduce the quality of dried flowers and essential oils volatize in extreme heat. Therefore, lavender was not harvested first thing in the morning or during temperatures greater than 90F. Spikes from each plant were cut, placed in a Uline cloth bag, weighed in the field, and fresh weight recorded. Lavender was hung to reduce the moisture content for a few days but was not let to dry completely before distillation.

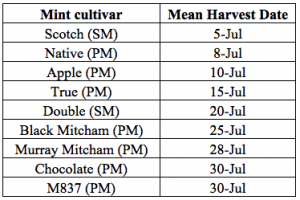

Mint Harvest

Mint leaves were harvested from second year plants for the first time in 2018. Because mint quality decreases once flower heads develop, mint cultivars were harvested once one flower head was observed. Flower scouting began on July 15th to ensure that leaves were not harvested too late. Using hedge sheers, mint plots were but to 4 inches above the ground, placed in Uline cloth bags, weighted in the field, and hung to dry completely. Table 4 indicates mean harvest dates for each mint cultivar in 2018. The mint harvest began on July 5th and finished July 30th.

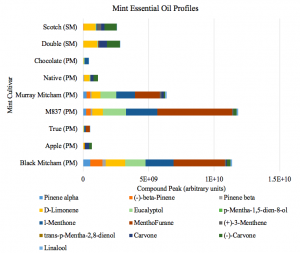

Distillation and Essential Oil Analysis

An EssenEx 100E (OilExTech, Oregon State University) was used to distill both lavender flowers and mint leaves (Image 3). Lavender was distilled fresh after 2-3 days of drying per ISO standards and previous study (Swift 2012). One cultivar was distilled at a time. The glass distillation vessel was filled leaving 1-2 inches of air at the top to get the largest volume of oil. All manual instructions available on the OilExTech website were followed. Oil was separated from evaporated water and pipetted into UV resistant glass vials. Because the amount of oil produced by each plant was so low, all oil from each cultivar was combined into one vial. Vials were shipped to the Metabolomics Facility at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY where Dr. Elena Rubio identified chemical compounds using FAME (fatty acid methyl esters) and GCMS (gas chromatography/mass spectrometry). Each mint and lavender cultivar was screened for 40 different compounds. Compounds that were not detected were removed from the data. Fourteen lavender compounds and 13 mint compounds are reported. All data was analyzed using JMP 14 either by t-test or one way ANOVA at the 0.05 level of significance.

In 2016, we began a preliminary variety trail before this NE SARE grant project began.

A pest 'cheat sheet' with photos was created to help growers identify lavender pests (see above link).

Lavender Pests

Insect pests pressure was low on lavender in both locations. The following were observed on lavender from 2016 – 2018 spittle bugs (Cercopidae spp.), tarnished plant bug (Lygus lineolaris), two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae), occasional Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica), and occasional caterpillar species. Spittle bug larvae were the most aesthetically bothersome to lavender growers but incur very little economic damage to lavender spikes. Tarnished plant bug adults feed on the developing lavender cells which causes deformed buds at harvest. Two-spotted spider mite arrived on Hidcote plants from the nursery in 2016. Natural enemy insects present in the field managed this mite population and most spider mites were under control 1.5 months after planting. One Hidcote plant desiccated and died from mite damage.

In 2017, Agdia tests indicated that no plants had arrived with phytophthora (P. nicotianae). Once plants were in the field, symptoms that appeared to have phytophthora symptoms did not test positive for phytophthora. However, fusarium and pythium were identified after plants exhibited “wilting” symptoms. The pathogens that appeared to show root rot disease symptoms were likely due to saturated soils in 2017. One sample was identified as simply having “wet feet” by the Cornell Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic. Leaf spots were also very common on lavender each year of the trial. Several lavender plants arrived from the nursery with septoria leaf spot which carried over into the field. Septoria symptoms decreased after transplanting as plants became established. It is unclear at this time what impact Rootshield had on the reduction in leaf spot symptoms. Lavender plants also showed leaf yellowing, one sample of which was identified as Xanthomonas hortorum. Further research is required to hone in on the exact symptoms of Xanthomonas vs. Septoria in the field. Plants did not arrive with yellowing, yet this discoloration appeared once plants became established.

Mint Pests

Very few insect or disease pests were present in mint plots. Occasional caterpillar and thrips species were recorded chewing on leaves. In the establishment year (2017), an unidentified scale species and powdery mildew were abundant on many mint cultivars in September long after mint would be harvested.

Winter Survival

Lavender Seed Germination Study

Lavender planted from seed showed very low germination rates. Preliminarily, the 50/50 mix of vermiculite and potting soil showed the higher germination rate with a mean of 36% (Figure 3). Potting soil appeared to hold too much water which vermiculite did not hold enough. Further replication of this study is required.

Figure 3. English lavender seed germination rate by soil medium. The 50/50 vermiculite/potting soil mix showed the highest germination rate while potting soil showed the lowest.

Harvest Dates

Essential Oil Yield

Essential Oil Quality

Discussion

Lavender

Planting lavender from seed is not recommended because lavender seeds are not identical to their parent plant. The offspring planted will be different than the true cultivar parent plant. Planting from seed is also viewed to be less efficient than buying plugs that are planted directly into the field. Based on the limited study conducted and reported in the 2017 project report, germination rates were low.

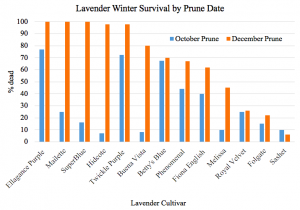

Winter Kill

Ellagance Purple, Twickle Purple, and Betty’s Blue had the lowest survival rate on both October and December pruning dates. Preliminarily, these cultivars are not as winter hardy in northeastern New York. Sashet and Folgate had the least amount of winter kill when pruned in October and December, suggesting that these two cultivars are more tolerant of the fall pruning practice and our winters. The survival rate of Maillette, SuperBlue, Hidcote, Buena Vista, and Melissa can be improved by pruning in early fall compared to December.

Pests

Lavender has very few insect pests yet the bacterial and fungal pathogens of lavender are of much greater concern for commercial production in the Northeast region compared to more arid locations. We have seen preliminary cultivar differences in susceptibility to leaf diseases, yet we do not know how much these leaf diseases impact yield or quality of lavender. In other crops, Septoria (one leaf disease) will take its toll on plants slowly overtime and can be economically damaging to yield of perennial crops.

Oil Yield and Quality

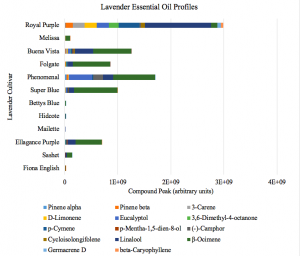

Lavender harvest for oil lasted 2-4 weeks and depending on the season, harvest may begin between June 15th and July 5th. Harvesting lavender for cut flowers would last up to 2.5 months (June-August). The amount of lavender oil produced by the different cultivars was statistically different (P < 0.002). On average, 255g of fresh L. angusifolia lavender flowers yielded 1.4mL of oil in this study. L. angusifolia is known to produce less oil than hybrid cultivars (Swift 2012). Distillation takes practice and our method should be perfected for further studies. Harvest date likely influenced oil profiles and the amount of oil measured. Several lavender cultivars contained beta-ocimene, a sweet herbal characteristic found in many perfumes. Linalool (common flower scent of spice) and eucalyptol (eucalyptus) were compounds detected in several lavender cultivars. Camphor is another important compound that varies between L. angustifolia and hybrids such as Phenomenal or Grosso.

Fall Pruning and Covering

Pruning lavender is a required agronomic practice. Plants that are not pruned will become woody, have a sprawling growth habit, and will not produce as many flowers. The current challenge is figuring out when and how hard to prune. More research must be conducted in order to make recommendations with confidence for northeastern growers. From our preliminary pruning study at Hay Berry Farm in Hoosick Falls, NY, the depth of pruning did not impact lavender survival when plants were also covered with row fabric. When plants were “green pruned” (2 inches above wood line) and not covered, significant winter damage occurred. Experienced growers in Oregon recommend pruning hard by Labor Day to allow green growth to return before winter. From our experience here in the northeastern NY, this is a good recommendation yet plants should also be covered with row fabric from November – early May. Pruning “hard” means cutting plants back into the woody stem, leaving 2 inches of wood above ground. This will yield strong spring growth and allow plants to remain tight with very little wood throughout their 20+ year life.

Covering lavender in our northern climate is advised. Lavender can withstand cold temperatures and snow without any problem. Winter damage occurs once plants come out of dormancy in February/March and there are cold winds that desiccate the plants. After pruning in early to mid-September allow a few frosts to occur so that they go dormant. The best recommendation for our region right now is to prune lavender into the woody stems about 2 inches off the ground by Labor Day to allow new leaves to develop before the first freeze. Then, cover rows with row fabric. Row fabric ranges in thickness from 0.10oz/cuft2 to 3.0oz/cuft2. As thickness increases so does the price. Moisture can build up under the thick fabric on warm spring days, increasing the risk of disease. Open up the tunnels on warm days (>50F). Our last frost date is around May 15th but may be different depending on your location. Do not remove covers until early-mid May.

Mint

Overall, mint cultivars grew vigorously and thrived in the wet 2017 spring/summer. We learned that mint should be cut back (down to the ground) in the fall in year 1 and after harvest in subsequent years. Scotch (SM), Double (SM), True, Apple, and Chocolate mints outcompeted weeds best and developed a thick stand. Spearmints survived the winter best on our rating scale as expected. However peppermints also performed well. In the establishment year, it is important to look for the arrival of scale insect on Scotch spearmint and powdery mildew on Apple peppermint. Overall, there were few insect and disease pests on mint cultivars in both locations. Mint harvest lasted for about 1 month in 2018 and depending on the season, harvest may begin between June 15th and July 1st.

Figure 5. Lavender plots before planting at Lavenlair Farm (top) and Hay Berry Farm (bottom).

Figure 6. Mint plots at Hay Berry Farm after transplanting (left) and before bloom (right).

Oil Yield and Quality

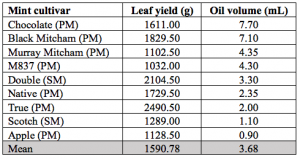

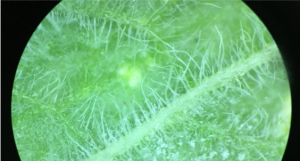

On average, 1590g of fresh mint leaves yielded 3.7mL of oil in this study. Double (SM) and True (PM) produced the most leaf material yet did not produce as much oil as other cultivars that produced less leaf material. The mint oils are located in leaf hairs, or trichomes, that secrete chemical compounds on the underside of leaves (Image 4). Although it may appear as though peppermints yielded more oil than the two spearmints, this is not statistically significant difference. According to EssexLabs in Washington state, Pulegone is a compound commonly found in mint that our lab was not able to test for. An important compound to measure in future studies, pulegone is an indicator of mint plant stress. A stressed mint plant (excess heat or pest pressure) will produce a higher volume of oil. However, that oil will have higher levels of pulegone and therefore be less marketable, adding a “harshness” to the mint oil. Pulegone levels between 1 and 2% are good oils, yet greater than 3% pulegone should be avoided. Harvesting during full mint bloom will also increase the amount of pulegone in the oil. As expected, different forms of menthol (mint) were abundant in mint oil samples. Limonene (citrus/lemon) and eucalyptol (eucalyptus) were commonly found in mint samples. Spearmints (‘Scotch’ and ‘Double’) showed their own distinct flavor profile compared to the more diverse and variable peppermints.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

https://www.canr.msu.edu/od/educational-technology/msu-community-id-instructions

Once you have an account, you can access the webinar modules. You can contact their Help desk for any questions.

Attached are a pdf of Dr. Calderwoods 4 presentations.

Participation Summary:

Consultations: People interested in growing lavender contact me with questions. Most of these people are in New York State. Two growers from Vermont and one from Massachusetts have gotten in touch with me. I estimate that in year 1 of this project I have worked with 50 experienced or beginning growers to assist them with lavender site selection, variety selection, pruning, pest management, and nutrient management. If they know about this project then they will also ask about mint. Overall, more people are interested in lavender. 50 people reached

Tours: Every few months the Cornell Cooperative Extension regional agriculture educators get together and visit a few farms in one of our counties. In June of 2017, the group came to Hay Berry Farm to hear about this project and see the recently planted plots. Lily Calderwood and Lawrie Nickerson gave a tour of the farm with research discussions. 10 attendees

Field Day/Workshops: One field day was held at Hay Berry Farm on July 12, 2017 and the second was held at Lavenlair Farm on July 25th, 2018. Lawrie and the Allen's shared her experience growing lavender while we walked through their blooming lavender. Then I introduced this SARE research project in the lavender and mint study plots. We then discussed methods of distilling herb oils as a high value product. 40 attendees total

Figure 1. Field Day attendees listen to Lawrie Nickerson explain why she is interested in adding lavender to her mainly blueberry farm (Hay Berry Farm, Hoosick Falls, NY).

Presentations: Lily organizes the NY Cut Flower Conference. She gave a 45 minute talk titled “Developing Lavender and Mint Production in the Northeast” which specifically introduced this project and discussed results and experiences from year one. Also at this event, there was a cut flower grower panel where 5 farmers discussed production, marketing, challenges, and successes. David Allen of Lavenlair Farm was on this panel. Aine Hardaker, research assistant, completed here BS thesis on this project. She gave the 2019 lavender and mint research presentation on this project at the 2019 NY Cut Flower Conference on January 7th, 2019. 100 attendees total

Curriculum Created: As a partial result of this project, Lily Calderwood was asked to create a series of 4 webinars on lavender production for a Lavender for Beginners curriculum. This educational curriculum led by Michigan State, Kansas State, and the US Lavender Growers Association will be available online in webinar format. It is currently in the review and editing stages. Managing Lavender_Presentation final

Learning Outcomes

- Understanding of lavender pruning and covering

- Necessity of covering lavender

- Better understand one method of distilling herb oils but would like more education on this subject

- Farmers learned who else is growing herbs for oil or cut flowers

- Farmers connected and learned from each other

Project Outcomes

Conducting this research and education opened cut flower and lavender growers eyes to the possibility of producing essential oil herbs but it also increased the knowledge that current lavender growers have about commercial production. People growing lavender already believe it to be profitable, although some new growers are not including their upfront costs to the profitability of the crop.

From a post-project survey sent out to lavender growers in NY in 2019, five growers indicated that they learned the following from this project: how to grow lavender, variety selection/winter hardiness, and essential oil production. One grower said "Thank you very much to the funders. This was a good research project to support and hope they support future lavender projects" and "I wish there were more workshops!" Growing lavender has gained a foothold in this region as a result of this study.

Areas for further research:

- essential oil distillation on small farms

- pruning depth and timing for lavender

- how and when to cover lavender

- education on the compounds included in lavender and mint quality results