Final report for ONE18-309

Project Information

This project trailed a series production methods for growing peanuts on a small scale in Pennsylvania and tracked expenses to determine potential profits on the produced crop. The field trial took place in 2018 and contained 16 different research plots trialing 2 varieties of peanuts, Tennessee Red Valencia and Schronce’s Deep Black. Three contrasting production methods were trialed for each variety: transplants v. direct seed; row cover v. no row cover; hilled beds v. flat beds. Final yields were measured and calculated based on a 100% plant survival rate. Results showed that direct seeded peanuts yielded a total of 22.02 lbs and transplanted peanuts yielded a total of 17.86 lbs. Research plots containing row cover yielded a total of 22.34 lbs and plots not containing row cover yielded a total of 17.54 lbs, and the difference in yield between transplanted plots was slightly higher at 2.87 lbs between the two techniques compared to the difference in yield between direct seeded plots at 1.93 lbs. Hilled beds yielded a total of 20.53 lbs and flat beds yielded a total of 19.35 lbs. The variety Tennessee Red Valencia yielded a total of 21.80 lbs and the variety Schronce’s Deep Black yieldeda total of 18.08 lbs. A potential net profit from the entirety of the plot was calculated at -$23.70. Though low actual yields and no profit were the result of this project, much insight was gained on potential best production practices to increase yields and efficiencies that could be considered when developing trials in the future. Outreach consisted of a presentation at the Pasa 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Conference.

To determine which technique and variety for growing organic peanuts on a small scale will produce the highest marketable yield for this climate and region based on these questions:

Can transplanted peanuts produce more than direct seeded peanuts? Does row cover increase the yield for either technique?

Do hilled beds increase yields?

When compared to Valencia peanuts, will black peanut varieties like Schronce’s Deep Black, produce larger yields while also creating a niche peanut product?

Each of these questions will be answered by measuring the weight in pounds of dried, marketable fresh peanuts in several categories for each variety. To determine what profit can be made based upon the results of this project and the price per pound that could be received through the market of Tuscarora Organic Growers Cooperative. Hopefully these numbers will encourage farmers to continue to grow and experiment with organic peanuts in this region.

Peanuts are traditionally grown in very specific regions of the United States. As a beloved food item, and with local and regional food becoming more popular every year, peanuts may have the potential to become a new market item for farmers in Pennsylvania. Specifically for the certified organic produce farmers that make up Tuscarora Organic Growers (TOG) Cooperative, the organic production of peanuts on their small-scale farms may have the potential to boost sales for member farmers and the cooperative by offering another niche produce item to their customers, many of whom are metropolitan-based high-end retail stores and restaurants who enjoy trying unique products. The cooperative may also have the ability to be at the forefront of this new market for fresh and organic peanuts. In addition, this product may help diversify income and product offerings in other TOG farmer enterprises, such as Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) sales and farmers market sales, especially during the fall and winter season. Conversations and experiences lead me to believe that trialing peanut production is worth the time. Already one farm within the TOG cooperative has grown peanuts as a trial crop for the past few seasons, with customers buying their limited, but entire supply. Another cooperative member, who will be the cooperating farmer, has also expressed interest. After growing peanuts as a trial crop in a hoophouse setting at a previous job, I also started to contemplate if this crop could be more seriously grown in Pennsylvania. Adding peanuts into a farmer’s operation can diversify crops and crop rotations, which further contributes to the sustainability and resiliency of their farm and farm ecosystem. As a member of the legume family, peanuts also have the ability to rejuvenate the soil with nitrogen, adding yet another way to harness the power of systems within the natural world around us. If our cooler climate enables us to have less of the pest and disease pressure of the south, this could also contribute to more sustainable peanut production and potentially make it easier for farmers utilize organic production practices. In addition, with an increasing uncertainty of seasonal weather patterns and the continuing shift of our global climate, the potential to expand a historically territorial crop like peanuts may prove to be an important undertaking if we hope to have these crops in the future. On a small scale, fresh peanuts may be the most easily profitable peanut product. However, on a larger and even more regional scale, the potential for production of peanuts in Pennsylvania could create new industries and businesses. Roasted peanuts and value-added peanut products could loom in the future for larger operations, if it proves to be a viable crop and enterprise here. The exploration of peanut growing and beyond in Pennsylvania has yet to begin, and thus the possibilities are limitless.

Cooperators

Research

Experiment Design:

For this project, we trialed two different peanut varieties: Schronce’s Deep Black and Tennessee Red Valencia peanuts. All seeds were obtained from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange. Both varieties were grown under 8 different parameters:

1) Transplanted, Hilled Bed, Without Row Cover

2) Transplanted, Hilled Bed, With Row Cover

3)Direct Seeded, Hilled Bed, Without Row Cover

4) Direct Seeded, Hilled Bed, With Row Cover

5) Transplanted, Flat Bed, Without Row Cover

6) Transplanted, Flat Bed, With Row Cover

7) Direct Seeded, Flat Bed, Without Row Cover

8) Direct Seeded, Flat Bed, With Row Cover

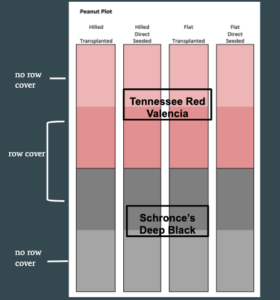

This totaled 16 different research plots within the field. The field consisted of 4 total beds, each 124 ft long. See diagram below.

Planting:

The field research for this project took place in 2018. On April 16th, three 72 cell flats each of Schronce’s Deep Black peanuts and Tennessee Red Valencia peanuts were seeded for transplanting in the field. The potting media used was a blend of local potting mix from Summer Creek Farm and Fertrell fertilizer that the cooperating farmer regularly used during the time of this project. The seeded flats were kept in a heated greenhouse and watered as necessary until planting day.

The research field was planted with seeds and transplants on May 26th into a field that had a previous overwintered cover crop of rye, which had been recently turned in. This planting day was delayed about a week due to unfavorable weather conditions for preparing the field. Following the research field design (Figure 1), four beds were laid out, about 5 ft apart, center to center, and 124 ft long. Each bed contained 4 research plots about 31 ft in length. Two beds were “hilled” by making raised beds. Drip tape was laid on top of each bed. Row cover was placed where necessary according to the research field design. Hoops were used to keep the row cover from touching the transplants but were not used for direct seeded peanuts covered with row cover. In the bed closest to a small patch of woods, plastic netting was preventatively draped and secured over hoops in the two research plots with no row cover as protection against animal feeding. All transplants and seeds were watered as soon as they were planted. Not enough seeds were ordered, causing several of the “direct seeded” research plots to be planted with less seeds than desired. It was noted approximately how many seeds were missing based on the unplanted row feet of each of these research plots.

During the growing season:

The patch was cultivated with hand tools on June 4th, about one week later. Many seeds planted in the field had sprouted by this time. Other weeding events took place by hand-pulling on 6/28, 7/24, and 8/9. Row cover was removed on 6/28. Netting remained in place until the plants became too crowded underneath. Watering took place as needed, which was not frequently due to a rainy season. A plant tissue analysis was performed on 7/19, and on 7/24, 20 lbs/ac total of 13-0-0 protein meal was added at the recommendation of test results.

Harvesting and drying:

Starting on 8/28 and again checking on 9/20 and 10/3, selected peanut plants were pulled in order to perform peanut maturity tests to help determine when to dig. The peanut maturity test used is commonly called the “hull scrape method.” (This method involves scraping off the outer layer of the pod to reveal the color of the mesocarp layer, which can tell you the maturity of the peanut pod.) Using the results of the hull scrape method and feeling the pressure to sow a fall cover crop in the research field, all peanuts were dug on 10/13 using digging forks. All peanuts were picked off plants, separated by research plots, and put into labeled mesh bags. At this stage, peanuts that were visibly immature were separated out and not collected into the mesh bags.

After reading that it is inadvisable to dry peanuts at temperatures above 85℉, the peanuts were put into a shallow drying rack on 10/14 in the farmer’s upper barn. The drying rack had a hard wire mesh bottom and top with solid sides. The dimensions were such that all sixteen bags of peanuts could be laid out flat and side-by-side. There was a continuous fan blowing through the bottom of the rack to aid in the drying, and the fan was periodically angled differently to ensure all peanuts were receiving direct air flow. Because drying took place in the barn, peanuts were exposed to less than ideal ambient air temperatures, which, at this point in the season, were getting close to freezing at night. Stacking the bags side-by side instead of on top of one another and using a fan were helpful to speed the drying process under these conditions.

About one week after being placed in the rack, the peanuts were checked for dryness. This was measured simply by tasting the peanuts and noting the amount of moisture that remained in the nut. The peanuts were left to dry in the rack with the fan blowing on them for a few more days. The peanuts were moved into a space heated to about 85 degrees at the very end of October. It was noted that after about another week and a half, the peanuts dried out further, and this was again measured by tasting the peanuts. Based on taste and the presumption that they had dried to a desired range, all peanuts were sorted on 11/13 and 11/14 to separate out the unmarketable or immature peanuts that did not have fully mature seeds inside the pod. Because the peanuts had fully dried, it was easy to sort out the unmarketable or immature peanuts based on their shriveled appearance. After sorting, the marketable peanuts from each research plot were weighed separately.

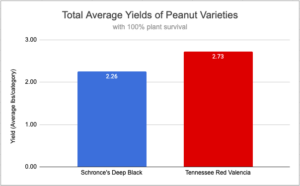

Due to a seed shortage during planting (as noted in the Materials and Methods section), varying field germination, and pulling plants for peanut maturity tests, final population counts varied for each research plot. As a result, yield results were calculated based on 100% plant survival for each of the 16 plots in order to properly answer the project objectives. The graphs below report averages for each production method and the two varieties of peanuts.

Results of Objective 1: To determine which technique and variety for growing organic peanuts on a small scale will produce the highest marketable yield for this climate and region, based on yield.

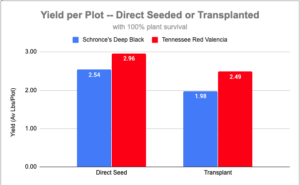

Can transplanted peanuts produce more than direct seeded peanuts?

Direct seeded peanuts yielded a total of 22.02 lbs and transplanted peanuts yielded a total of 17.86 lbs. These results tell us that it could be possible to consider direct seeding peanuts in our climate.

Discussion: Conventional thought is that transplants would have a head start on development over direct seeded peanuts and thus have more mature peanuts at harvest time. The peanut transplants grew rapidly in the cell flats, and as a result, at planting time, they had grown to be overmature with some transplants even flowering. An overmature transplant can actually set back production due to the stress of growing in inappropriate conditions, and we think this may have contributed to our results.

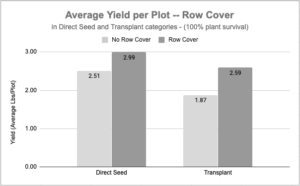

Does row cover increase the yield for either technique (transplanting and direct seeding)?

Research plots containing row cover yielded a total of 22.34 lbs and plots not containing row cover yielded a total of 17.54 lbs. The yield increase was greater between these techniques in transplanted research plots with a difference of 2.87 lbs compared to direct seeded research plots with a different of 1.93 lbs.

Discussion: Because the peanut plant creates a perfect flower, we were able to leave the row cover in place for nearly a month without concern that pollination would be affected. After taking the row cover off, we observed overall that plants growing under the row cover appeared to be larger in size and had better coloration. We also observed that peanuts direct seeded under row cover seemed to germinate better than those direct seeded without row cover. However, despite some of these observations and results, the use of row cover could be inefficient depending on the production system in place, and these differences in yield may not be enough to justify the use of row cover for some farmers.

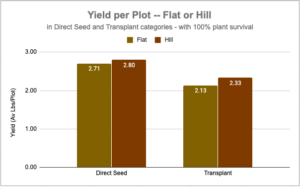

Do hilled beds increase yields?

Hilled beds yielded a total of 20.53 lbs and flat beds yielded a total of 19.35 lbs. This difference was not as great compared to the results of other trialed techniques.

Discussion: Many vegetable farmers, including the cooperating farmer in this project, build raised beds with a bed shaper for their production system to provide a more ideal growing environment for their crops. Because this technique was already built into the cooperating farmer’s system, hilled beds were made with the bed shaper at the beginning of the season for this project, whereas a traditional practice at larger peanut farms is to hill beds after the plants have reached a particular height. Hilling beds at planting time instead of waiting could have influenced these results. However, these results may also indicate that the farmer could decide whether to use hilled beds or not based on their preferred production system and not have a sizable impact on yield.

Which variety of peanut will produce larger yields?

The variety Tennessee Red Valencia yielded a total of 21.80 lbs and the variety Schronce’s Deep Black yielded a total of 18.08 lbs. These results tell us that Schronce's Deep Black peanut might not be as productive of a variety.

Discussion: In particular, in our direct seeded research plots, our observations seemed to indicate that Tennessee Red Valencia peanut seeds germinated better than Schronce’s Deep Black peanut seeds. And in making observations throughout the season, Tennessee Red Valencia peanut plants typically seemed larger overall and had a greater quantity of peanuts growing than the Schronce’s Deep Black peanut plants. Interestingly, when using the “hull scrape” method to determine the appropriate harvest window, it was observed that Schronce’s Deep Black peanuts were more mature at the time of harvest than the Tennessee Red Valencia peanuts. However, this fact did not seem to influence the final yield results in a significant way.

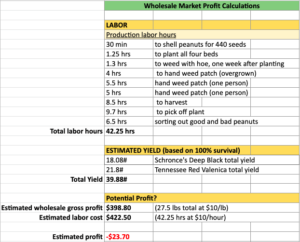

Results of Objective 2 - To determine what profit can be made based upon the results of this project and the price per pound that could be received through the market of Tuscarora Organic Growers Cooperative.

To determine profitability, we decided to only track the labor expense category, as that is normally one of the biggest expenses on any farm. A final yield was calculated based on a 100% survival rate and a wholesale price of $10/lb was estimated based on previous wholesale prices from Tuscarora Organic Growers Cooperative and conversations with a small scale peanut farmer. The estimated hourly wage for labor at $10/hr. Our results, even based on a 100% plant survival rate, show that if the crop from this project would have been marketed wholesale, it would have not been a profitable crop. The calculated net profit was -$23.70.

Discussion: Though we only have one year of data to look at, calculating the potential profit highlighted concerns that would likely need to be addressed to make this profit-yielding crop. Tracking labor hours showed that using hand weeding and harvesting techniques takes up a lot of time and money. Strategies to make these processes more automated with the help of cultivation and harvesting equipment could potentially decrease the labor needed. It’s likely that cultivation equipment already available to the small scale farmer could be used to cultivate the peanut plants in their early stages of growth before the plants start to peg. A quick internet search also shows that there is small scale equipment from around the world to aid in harvesting, removing peanut pods from the plants, and shelling. Actual overall yields were also lower than we were anticipating, which we think were in part due to various challenges in with transplant growth, field preparation and germination, and fertility issues partway through the season.

Additionally, the cooperating farmer chose to trial selling peanuts for a short time at his farmers market stand in Boalsburg, PA. He reported that a small number of customers expressed interest in fresh peanuts. The cooperating farmer speculated that selling them already roasted would appeal to a greater number of people.

In this project, we sought to trial different production methods for growing peanuts on a small scale based on methods used in research trials or by other farmers in order to find out what may be most appropriate for the climate of Pennsylvania. We also sought to determine the potential profit that could be made by determining a wholesale price and tracking expenses.

Though the results of this project did show differences between production methods, it cannot be fully determined if these differences are significant, because there was no replication of the field trial. Results indicated that direct seeded peanuts yielded more than transplanted peanuts. The use of row cover yielded more than not using row cover, especially in transplant research plots. Growing the crop in hilled beds yielded more than growing in flat beds, but this difference was small compared to other production methods tried. The peanut variety Tennessee Red Valencia also yielded more than the peanut variety Schronce’s Deep Black. We did calculate a negative profit for this crop, which illuminated the need for more efficient systems to cut down on labor and production improvements to increase yield. The potential profit per research plot was not calculated however. A trial of direct marketing the peanuts at the local farmers market resulted in some observations about potential differences in wholesale and direct-to-consumer marketing.

The cooperating farmer, John Eisenstein, would like to trial more peanuts in the future and is using the results of this project to make more informed decisions about the production methods that could work for his farming systems. In the future, John plans to plant just Tennessee Red Valencia and to direct seed all of his peanuts. He does not plan to push the seeding date any earlier due to challenges with spring field preparation and potential cool weather influencing germination. Due to soil fertility issues that were expressed in the plants during the trial year, he plans to put down nitrogen fertilizer applications before planting. The use of tractor cultivation and trialing the use of an undercutter bar for harvest are also easy ways for John to cut down on labor that he plans on incorporating. John will likely direct-market future peanut crops with the goal of selling them roasted for a ready-to-eat product.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Outreach activities included giving a presentation at the 2020 Pasa Sustainable Agriculture Conference entitled about project results and lessons learned. A copy of the final report will also be given to farmers who belonged to Tuscarora Organic Growers Cooperative.

Learning Outcomes

The cooperating farmer, John Eisenstein, would like to trial more peanuts in the future and is using the results of this project to make more informed decisions about the production methods that could work for his farming systems. In the future, John plans to plant just Tennessee Red Valencia and to direct seed all of his peanuts. He does not plan to push the seeding date any earlier due to challenges with spring field preparation and potential cool weather influencing germination. Due to soil fertility issues that were expressed in the plants during the trial year, he plans to put down nitrogen fertilizer applications before planting. The use of tractor cultivation and trialing the use of an undercutter bar for harvest are also easy ways for John to cut down on labor that he plans on incorporating. John will likely direct-market future peanut crops with the goal of selling them roasted for a ready-to-eat product.

Project Outcomes

Though we were able to trial and obtain results for different production methods of growing peanuts on a small scale, the lack of a duplicate trial, especially when trialing such a new crop for the region, hindered the ability to come to clear conclusions. Trialing this project for a second year would have given us the opportunity to adjust certain procedures to increase overall yields and efficiencies like reconsidering the growing out of transplants, earlier applications of fertilizer, and better use of mechanized equipment. A second trial year may have also given us the opportunity to trial this project in a more reasonable weather year than what occurred in 2018. 2018 was the wettest year on record in Pennsylvania, with many crops suffering from the wet conditions and lack of sunny days. Though not included in the labor hours, it took time to determine maturity levels in order to plan a harvest date. Attention should also be placed on more efficient ways to determine maturity and how late into the season peanuts can be harvested.

We only calculated a hypothetical profit for the crop through a wholesale outlet, and though the process was important to illuminate some of the bigger expenses involved, this still falls short of determining how these peanuts would have actually sold in the current market environment. Though the addition of trailing peanut sales at the farmers market helped to shed light on other marketing opportunities, more research is needed on the best way to market peanuts grown at this scale.

Ultimately, this project produced low yields and a lack of return in profit, which could be an indication that peanuts might not be worth the effort to grow at a small scale in our region. At the same time, some of the challenges encountered during this project are to be expected when trialing a new crop. These results could provide enough of a foundation for future projects, and several explanations and solutions to the challenges we encountered are offered throughout the report so that they can potentially be avoided in the future. This project would also give small scale growers enough information to trial a small plot of peanuts on their own. However, this project does tell us that more work needs to be done to determine if farming peanuts in Pennsylvania is a truly viable endeavor.