Final report for ONE18-325

Project Information

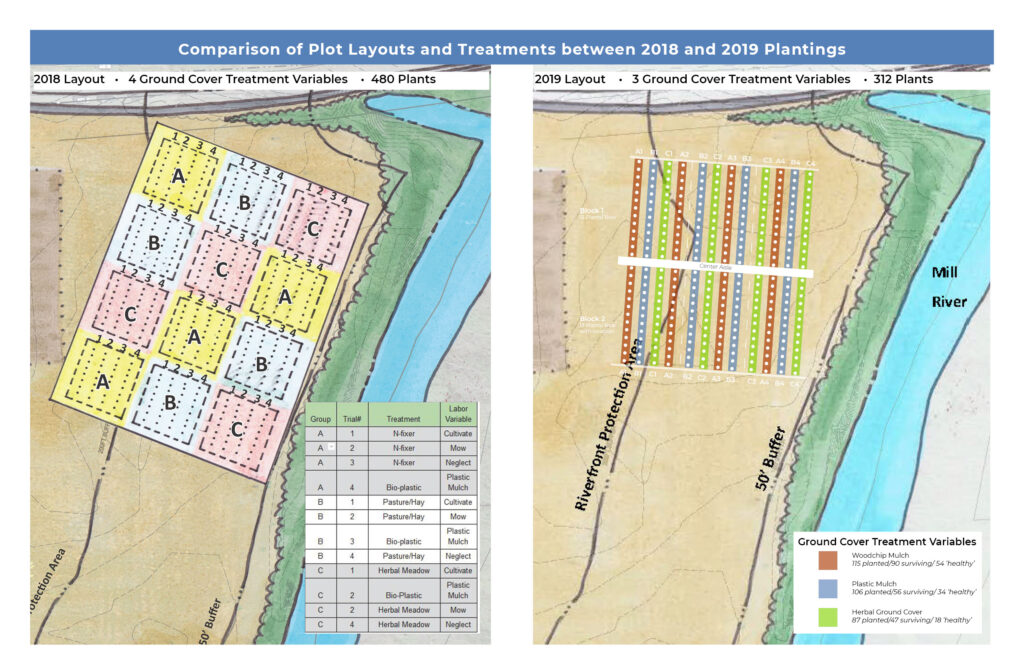

This study explored which type(s) of ground cover/ weed suppression management would allow for the lowest cost establishment of productive woody crops in the riprian areas of cultivated farmland. A one-acre cultivated field on Wisnooski silt loam located within the 10-year flood plain of the Mill River in Florence, Massachusetts was selected for the establishment of a planting of sambucus canadensis, black elderberry. After a crop failure in 2018 attributed to very dry weather, we simplified our approach to examine the effects of three ground cover treatments on the establishment of seven different varieties of elderberry over the course of the 2019 growing season and spring of 2020.

The Ground Cover Treatment variables (GCT's) consisted of:

- Wood Chip Mulch - 3-4" arranged in a 24" diameter ring around each plant

- Plastic Mulch - 4'-wide weed block landscape fabric was installed continuously within the row with 10" dia. circles cut out around each plant

- Herbal Meadow - A mixture of medicinal herbs including red clover was seeded each row.

Four replications of each GCT were established, each with t-tape style drip irrigation. Observations of plant health, field conditions, and ground cover conditions were made three times during the 2019 season (June, August, September) and three times during the spring of 2020 (March, April, May). Plant health was classified as 'Healthy', 'Weak/Diseased', or 'Missing/Dead'.

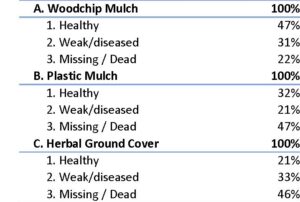

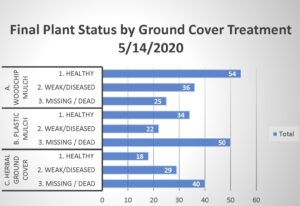

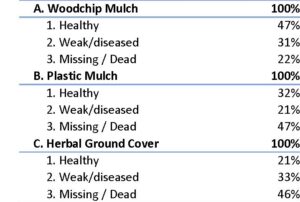

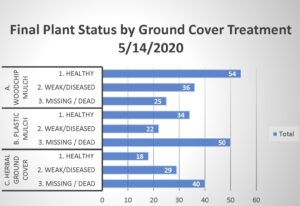

Of the 308 plants confirmed as planted in 2019, 106 (34%) received a final rating of 'healthy', 87 were rated as 'weak/diseased' (28%), and 115 rated as 'missing/dead' across all Ground Cover Treatments. While this aggregate performance is worse than expected, there was significant difference between the treatment groups.

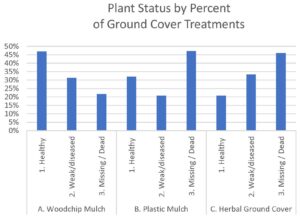

Ground Treatment A- Wood Chip Mulch performed the best with 69% survival, while Ground Treatment B and C had only 53% and 54% survival, respectively. had both the highest 'healthy' plants percentage (47%) and the lowest confirmed mortality (22%).

Ground Treatment A- Wood Chip Mulch performed the best with 69% survival, while Ground Treatment B and C had only 53% and 54% survival, respectively. had both the highest 'healthy' plants percentage (47%) and the lowest confirmed mortality (22%).

Based on observations made over the '19 and '20 growing seasons, we speculate this is due to four factors: 1. Better overall moisture retention than treatments B and C, 2. Lower winter rodent damage rates as compared to the plastic mulch, 3. Less mechanical damage caused by unsecured plastic mulch or from manual cultivation in the Herbal Ground Cover, and, 4. Less weed competition than in the Herbal Ground Cover.

Percentage of Plants in Each Status Class by Ground Cover Treatment

While the Wood Chip Mulch performed better than the other GCT's, our research team believes more investigation into the effects of these or similar treatments on the establishment success of wood crops is warranted due to the variability of irrigation and cultivation during our study.

The goal of this project is to trial establishment methods for Productive Agricultural Buffers (PABs) that reduce the labor and economic barriers preventing farmers from adopting these climate-smart practices. Specifically, we examined the effects of different cost-effective ground cover and weed management during the establishment of black elderberry, Sambucus canandesis, on cultivated lands subject to flooding. This versitile crop has established markets for its flowers and berries, and though it is commonly wildcrafted, it remains underutilized as a cultivated crop. A successful project will provide regional farmers with a new tool to mitigate risk in an economical way and supply our region with a valuable, local nutraceutical.

This project is conducted as a partnership between Susan Pincus, the owner of Sawmill Herb Farm (SHF), a small, diversified, fresh herb farm located in Florence, MA and Regenerative Design Group (RDG), an ecological landscape design and planning firm serving farmers and land owners throughout the Northeast.

Susan is looking to expand her operations onto a rented, 6 acre parcel in the 10-year floodplain but is keen to manage risk and cost. This project will also benefit Grow Food Northampton, a farm advocacy non-profit catalyzing sustainable farming locally, managing the 400-member Community Garden, and currently renting land to Susan. A successful project will refine methods to reduce establishment costs and ongoing maintenance for elderberry, or further the development of profitable establishment methods.

In the hilly, glacier-scoured landscape of the northeast and much of the world, the most fertile farmland often sits in the floodplain of rivers and streams. Due to economic pressure to maximize yield and right-to-farm exemptions from many environmental regulations, it is common practice for farmers to till these productive soils to the edge of river banks. This practice, however, exposes farmers and the ecosystem to risk and degradation. During regular rain events, storm water runoff from riparian croplands carries nutrients and invaluable soil into adjacent water bodies, lowering water quality, farm revenue, and the long-term productive capacity of those fields. Catastrophic flooding can result in even greater losses of farmland; this problem has been on the minds of many low-lying farmers since Hurricane Irene, which delivered over $20 million of damage to 9,100 acres and 476 farms in Vermont alone. (Impact of Irene) Here in Massachusetts we were left with startling imagery of local crop fields washed away, blanketed in sediment and strewn with large debris that floated up from the river.

What makes this problem even more significant is the fact that large rainstorms are becoming increasingly common in the region due to climate change. According to the National Climate Assessment, “the Northeast has experienced a greater recent increase in extreme precipitation than any other region in the United States.”(Agriculture and Ecosystem Impacts). The history-making 2017 hurricane season is acutely relevant; it is difficult to comprehend the scale of destruction that would result if a storm the magnitude of hurricane Harvey hit New England, bringing 4 or 5 times the rainfall of Irene over the course of just a few days. As these storms increase in frequency, it is inevitable that another “big one” will hit New England farms; the only variable is whether or not our farmers are prepared.

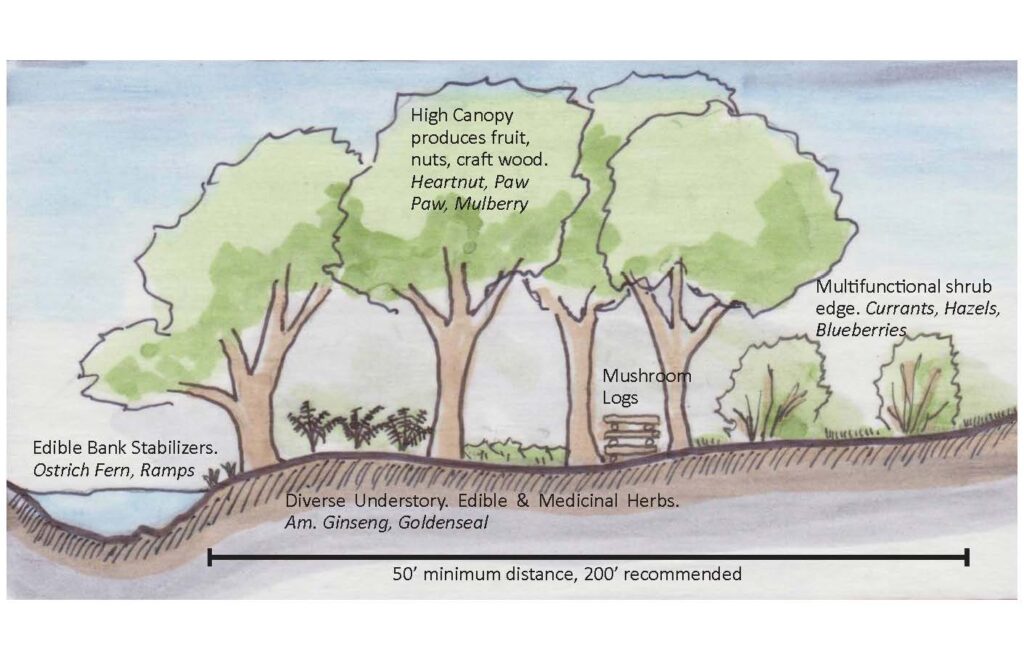

Riparian buffers - strips of trees and other vegetation that serve as a “living armor” to attenuate the force of rising floodwaters - have long been promoted by the USDA as a strategy to mitigate the destruction from large storms. Unfortunately, the opportunity cost of a riparian buffer is prohibitively high for many farmers who are unwilling or unable to accept the permanent loss of productive land to offset the periodic risk of flooding. Productive Agricultural Buffers (PABs) are an innovative solution intended to address this dilemma; they include species that have both ecological and economic function, improve riparian resiliency, and also provide a marketable yield for farmers.

Unfortunately, adoption of PABs is limited due to high establishment costs and lengthy return-on-investment timetables. Regenerative Design Group (RDG) sees a significant opportunity to develop improved mulching methods for establishing and maintaining a PAB in the floodplain that will reduce four main costs: weed suppression, fertilizer, irrigation and labor. If successful, this project will provide regional farmers with a living model of a land management system that is both economically and ecologically sustainable and provide a new, high-value, sustainable crop for our local food system.

Productive Agricultural Buffers can protect water quality and reduce flood damage to cultivated lands while producing diverse crops for farmers.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

Research

The impetus for this project is to identify the most cost and labor effective ways for farmers to convert annual or other high-disturbance agriculture systems into more flood-resilient cropping systems. Together Saw Mill Herb Farm and Regenerative Design Group worked together to convert a field that has cycled between annual crops and low-quality pasture for decades, into an elderberry orchard on the Mill River in Northampton. Originally planned as a two growing season project for Spring 2018 to Fall 2019, a crop failure in 2018 and refinement of the methods extended the project into June of 2020.

In 2018, we selected three cultivars of elderberries, Marge, Bob Gordon and and York, that provided good quality flowers and berries for herbal preparations and direct sale. The planned planting count for 2018 totaled 480 plants. When replanting in 2019, several additional varieties along with wild types propagated from local plants were added, bringing the total composition to a mix of 7 varieties for a total of 312 plants consisting of:

- Adams (48 Plants)

- Bob Gordon (68 Plants)

- York (12 Plants)

- Nova (8 Plants)

- Ranch (32 Plants)

- Marge (4 Plants)

- Wildwood (8 Plants)

- Wild Propagated + Unknown Varieties (128 Plants)

Field Preparation + Planting 2018:

Beginning in mid-April, our team from Regenerative Design Group and Sawmill Herb Farm staked a one acre plot in the historically tilled field located along the Mill River.

We disc-harrowed with a light disc to initiate three rounds of stale-bedding over 6-weeks. This practice was selected because of the intense weed pressure observed in the plots. Extremely dry conditions during this period may have limited the germination of weeds from the seed bank. On May 25th, after a final disc-harrowing and hand weeding was conducted.

On Wednesday, the 23rd of May, Susan Pincus and Eric DePalo, an RDG team member, retrieved 384 unrooted hardwood cuttings from John Hayden at the Farm Between in Jeffersonville, Vermont. The cuttings had been taken in the late winter by Hayden and stored in plastic to maintain moisture. Though we were concerned that the cuttings would either be desiccated or rotted due to their long-time in storage, all appeared to be in good condition. On May 25th, after two days of storage in ambient temperature and just prior to planting, the cuttings inspected again. Out of the three varieties, Marge and Bob Gordon fared the best. The York cuttings showed significant rotting. To account for these losses, the 16-20" cuttings were divided in half and soaked in water.

On Thursday, the 24th of May, Susan and Eric, with help from Sawmill Herb farm interns, laid out the 12 experiment blocks, staking and flagging the corners. We also marked the location of each row of elders within the blocks, laying stakes on the northern and southern edges so a measuring tape could be pulled tightly between them. We seeded the cover crops accordingly within the blocks. Site conditions were extremely dry - due to the sandy loam and the lack of rain this spring, we felt as though were were working in desert-like conditions.

On Friday the 25th of May, we had a planting work party with a dozen Smith summer interns, several Sawmill Herb Farm interns and several volunteers from the community. We broke into teams: scuffle-hoers who knocked back some of the quack grass which had survived the stale-bedding; measurers who dug holes where the elders were to be planted; composters who dropped compost into the holes; irrigators who soaked the holes with water from a long hose leading back hundreds of feet back to the nearest spigot; and planters who inserted the elders into the composted, irrigated holes. Coordinating so many unskilled people proved to be a challenge. Some of the holes were located at slightly incorrect intervals, and the three varieties were not placed entirely within in the 1-2-3 pattern we had designed. Approximately 5% of the elders were planted upside down. The extra cuttings we had left (from cutting-in-two the excessively long cuttings) were planted at one-foot spacing in a separate nursery bed.

It did rain slightly over the weekend, however the dry spring persisted. Despite installing drip tape along each row, we watched the elders dry up and die over the next few weeks. The majority of the covercrops also failed to germinate.

In mid-June it was determined that only approximately 100 plants were still alive and the decision was made to rescue these plants and work to establish more conducive field conditions for replanting in the spring of 2019. Susan rescued the surviving elders from the field, potting these plants to increase their chance of rooting, and prepared the field for another covercrop planting. Susan mowed and sowed a new cover crop of Sudex grass in July 2018. The establishment was also spotty and resulted in a mix of Sudex, crab grass, quack grass, and many broadleaf weeds. The field was then mowed again in October in preparation for replanting in 2019.

In summary, our project suffered a complete crop failure due to poor timing of the planting, drought, and intense weed pressure in 2018. Katie Campbell Nelson from UMass Extension and Carol Delaney joined Susan Pincus and Keith Zaltzberg for a site visit on August 9, 2018. After observing field conditions and discussing the research purpose, a revised experimental design was proposed. This modified program is described below .

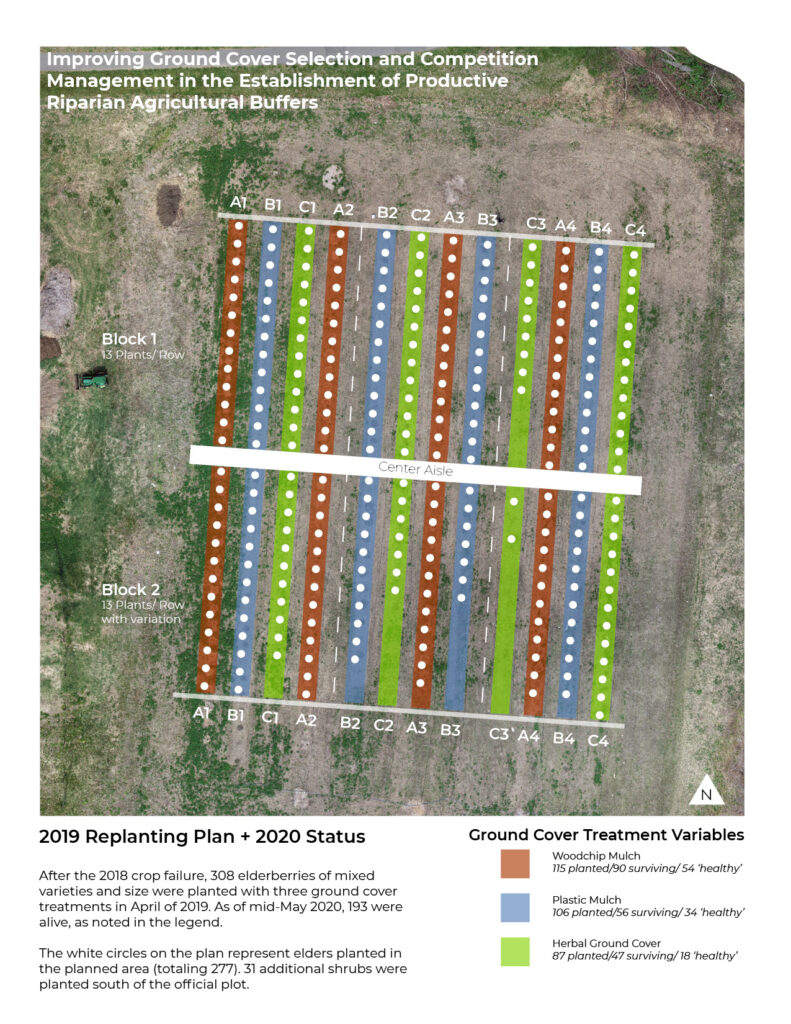

Replanting in 2019 with more robust planting stock

Rather than replicating the experiment of direct planting cuttings into our droughty soil, we decided to plant well rooted cuttings and containerized plants. In addition to the 75 of the original cuttings that survived the winter in pots, we received some rooted cuttings prepared by interns from the Smith College Botanic Gardens under the direction of Gaby Immerman and Susan Pincus prepared in the fall of 2018. Because our new planting plan required 312 plants, more than 200 3" potted elderberries were purchased in March of 2019. In total we verified planting 308 elderberries of 7 varieties with three ground cover treatment variables.

Softwood cuttings taking root in the greenhouses of the Smith College Botanic Garden.

Four replications of each ground cover treatment was established, each with t-tape style drip irrigation.

Planting occurred over two days in April of 2019 with members of the RDG team and Saw Mill Herb Farm's crew.

Each plant received 1-qt of compost applied around its roots and was hand watered.

Ground cover treatments around the plants were established over the months of April and May.

-

- GCT C- Herbal Ground Cover was seeded on April 4

- GCT A- Wood Chips were applied on May 17

- GCT B- Plastic Mulch was applied on May 24

Drip irrigation was installed in April of 2019 and run weekly.

Observations of plant health, field conditions, and ground cover conditions were made three times during the 2019 season (June, August, September) and three times during the spring of 2020 (March, April, May). Plant health was classified as 'Healthy', 'Weak/Diseased', or 'Missing/Dead'. An online database was used to record observations. Of the 308 plants confirmed as planted in 2019, 106 (34%) received a final rating of 'healthy', 87 were rated as 'weak/diseased' (28%), and 115 rated as 'missing/dead' across all Ground Cover Treatments. While this aggregate performance is worse than expected, there was significant difference between the treatment groups.

Ground Treatment A- Wood Chip Mulch performed the best with 69% survival, while Ground Treatment B and C had only 53% and 54% survival, respectively. had both the highest 'healthy' plants percentage (47%) and the lowest confirmed mortality (22%).

Ground Treatment A- Wood Chip Mulch performed the best with 69% survival, while Ground Treatment B and C had only 53% and 54% survival, respectively. had both the highest 'healthy' plants percentage (47%) and the lowest confirmed mortality (22%).

Based on observations made over the '19 and '20 growing seasons, we speculate this is due to four factors: 1. Better overall moisture retention than treatments B and C, 2. Lower winter rodent damage rates as compared to the plastic mulch, 3. Less mechanical damage caused by unsecured plastic mulch or from manual cultivation in the Herbal Ground Cover, and, 4. Less weed competition than in the Herbal Ground Cover.

Percentage of Plants in Each Status Class by Ground Cover Treatment

While the Wood Chip Mulch performed better than the other GCT's, our research team believes more investigation into the effects of these or similar treatments on the establishment success of wood crops is warranted due to the variability of irrigation and cultivation during our study.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

In 2018, due to a total crop failure, we scaled back our education and outreach activities from our original plan.

The activities we undertook included:

- A planting workshop with interns from the Smith College Botanic Garden

- The publication of two articles on productive conservation and the SARE project at www.regenerativedesigngroup.com: Productive Conservation Along the Mill River and Award announcement - Productive Conservation

- RDG also conducted a series of 4 consultations with Susan Pincus at Saw Mill Herb Farm on the planting and management of the experiment.

- One presentation at the 2018 Summer NOFA Conference, described below. The farm tour scheduled for the Summer NOFA Conference was cancelled.

Workshop Title: Productive Conservation for Flood-Prone Fields

Presenter: Keith Zaltzberg

NOFA Summer Conference August 2018

How can farmers improve the resiliency of riparian areas in the face of climate change while also producing food and salable crops for their communities? This workshop outlines the concept of Productive Agricultural Buffers and introduces participants to the site of a SARE-funded experiment establishing 500 elderberry bushes along the Mill River this year.

Objectives:

- Promote strategies of productive conservation that build on-farm climate resilience, enhance watershed-scale ecosystem performance, and support farmers’ bottom line.

- Share design and assessment tools to help farmers make better decisions for managing natural and soil resource areas.

- Increase landscape ecology literacy and design capabilities within the farming community of the northeast.

- Create a critical mass of farmers and farm-supporters to advocate for policy change and funding to implement productive conservation in the Northeast.

Productive Conservation for Flood Prone Fields_NOFA Summer2018

Learning Outcomes

The greatest learnings from the 2018 growing season came from the knowledge we gained around selecting and managing elderberry propagation materials. While we originally proposed to plant rooted cuttings, the cost of these cuttings were prohibitive. After much discussion with elderberry farmer John Hayden, we decided to purchase unrooted hardwood cuttings.

Due to a wet early spring and equipment availability, our planting was delayed until very late May. Despite installing drip tape, the unrooted cuttings desiccated in the extremely dry soils. We believe this was exacerbated by the fact that we divided the 18-24" cuttings we received into very short stakes. In the future we recommend planting thicker live stakes, a minimum of a pencil width, with at least three leaf nodes below ground.

Project Outcomes

Working on this enhanced each member of the team's ability to collaborate on the collection and tracking of ecological and agricultural data. Using the online database application Airtable, multiple investigators were able to make and record observations about plant health, field conditions, weather, and other notes on their laptop, tablet, and smartphone. This data was then available to all collaborators for analysis via download to a spreadsheet application.

One of the greatest successes of the study has been in building the relationship between RDG and Saw Mill Herb Farm. We've discussed continuing shared management of this planting and partnering on other projects.

Through the fall of 2019 and 2020, Regenerative Design Group has consulted with at least 5 farmers in New England planning to integrate woody crops into their riparian or other more fragile crop and grazing land. In all cases, the experiences gained in this study has resulted in RDG advising farmers to minimize disturbance of stable ground cover, protecting trees and shrubs from rodents, and using woodchip mulch to retain soil moisture and boost microbial activity. At least two of these farmers has taken that advise to heart.

Over the course of the two-and-a-half growing seasons that this study spanned, we've learned a number of lessons about experimental design, crop selection, and field preparation in the face of climate change. While the findings of our investigation do not conclusively answer our design question, we believe these lessons may support other farmers in making better decisions about establishing woody riparian buffers.

Experimental Design: The approach and methods of this study were designed to identify which type(s) of ground cover/ weed suppression would allow for the lowest cost successful establishment of woody crops in riprian areas of cultivated farmland. In our initial planting of 2018, we used four different treatments including a ‘neglect’ option and a ‘meadow’ option. Due to our crop failure and with the assistance of SARE and UMass Extension staff, we were able to refine our approach to align with methods farmers would be more likely to employ. This included eliminating the ‘neglect’ option and creating a ‘relay planting’ of an herbal meadow that integrated into the production scheme of Saw Mill Herb Farm. The three treatments of woodchips, plastic mulch, and a relay planting, with the additional refinements to both crop selection and site preparation discussed below, is an experimental design we believe worth trialing again. We would also recommend extending the experiment period to three complete growing seasons as this better reflects the typical establishment period of shrubs and trees.

Site + Crop Selection: The Winooski silt loam of our 1-acre floodplain the site is listed as moderately well-drained ‘Prime Farmland’. Our soil tests and site observations revealed a soil with low organic matter, very low fertility, and an extraordinary seed bank resulting in strong weed pressure. We intentionally selected this site to represent a ‘real-world’ example of a field farmers might consider for a change of crop system and management. Unsurprisingly, these conditions made successful establishment very challenging.

One unexpected factor that may have contributed to the heavy mortality in both 2018 and 2019 was the droughtiness of the soils. Given the adjacency of the field to the river, we made the erroneous assumption that the soils would have better than average moisture levels and as such selected the moisture loving elderberry as our crop species. In retrospect, a species with a greater tolerance of dry soils may have proven more successful under all ground cover treatments.

Field Preparation + Management: In order to establish the seeded ground cover treatments and travel lane cover, we sought to reduce weed pressure and prepare a suitable seedbed through stale bedding in 2018 and 2019. However, we experienced poor germination of both the seedbank between cultivation episodes and the seeded ground cover treatments, likely due to the unusually dry conditions in May and early June in ‘18, ‘19, and ‘20. Crabgrass and other annual weeds came to dominate the field after rains arrived later in June. As evidenced in the aerial image taken on May 8, 2020, much of the field is still barren. Because one of the primary benefits of converting cultivated land to woody crops is increased resistance to flood erosion, a field preparation approach that minimizes bare ground is preferable. In our case, we believe that more consistent and widespread irrigation after disturbance would have likely improved germination of both weeds and desired ground covers. Another promising method we would like to see trialed would be planting through the residue of a fall-planted cover crop such as oat-pea or crimped rye.

Initially, we proposed ‘no active management’ around the newly planted elderberries. However the effects of both weed pressure and rodent damage was significant. This suggests that some additional labor to enhance survival may be worth the investment.

Who might benefit: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that the Northeast U.S. will experience an increased frequency and magnitude of intense rain events resulting in more severe flooding between periods of extended drought and frequent heatwaves (https://statesummaries.ncics.org/). This means all farmers, but especially those in flood prone areas are likely to experience potentially damaging weather-related events more frequently.

Integrating woody crops in flood areas not only helps these fields resist erosion, but can help these farmers weather these storms by providing direct harvests of flood-resilient forage, fruit, herbs, and floras. Also, with technical service providers such as the NRCS and emerging payment-for-ecosystem-service schemes promoting the integration of more woody plants into and around annual cropping systems as a way to increase climate resilience and carbon sequestration, identifying low-cost, multi-benefit establishment techniques may provide alternative revenue streams for innovative farmers. Vegetable, small fruit, grazers, and other diversified farm operations who can integrate a novel crop type into their operations are the most likely candidates to benefit from improvements to implementation strategies such as those explored in this study.