Final report for ONE20-356

Project Information

Seaweed and shellfish aquaculture is a fast-growing industry in Maine, but most farms rely on only one crop and lack diversification options. Green sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis) represent an opportunity for multi-cropping on aquaculture farms, especially if seaweed can be cultivated on the farm for feed. This project tested kelp and sea urchin integration strategies on two farms in Maine over 2 growing seasons—an oyster farm in mid-coast Maine and on a seaweed farm in Downeast Maine. Juvenile urchins overwintered well on the oyster farm, and grew well in suspended lantern nets through the spring and summer, but experienced 100% mortality in early fall, with high temperature and a major rainfall event. The kelp line grown on the mid-coast oyster farm produced large, clean, healthy plants until May, when it quickly fouled and began to disintegrate. On the downeast seaweed farm, juvenile urchins grew in size over several seasons, with 100% survival. Kelp lines produced large, healthy, clean plants until July, when plants began to foul. Sea urchins fed on seaweeds added to the cages, as well as wild set algae and juvenile mussels throughout the year. Sea urchins are sensitive to high temperatures and salinity fluctuations, so will probably not be a viable crop on typical oyster farms that are sited in warmer, shallow areas near estuarine environments. Sea urchin cultivation is easily integrated into a cold water seaweed farm, and requires minimal time investment. Further work is required to develop high value markets for Maine farmed sea urchins to create a business plan for further commercialization. Several interns, volunteers, and employees assisted in the project, and the project has been shared with a wide range of audiences through in-person visits and field trips, online and in person talks and presentations, and individual consultations.

Goal: To develop year-round integrated grow-out strategies for green sea urchins and sugar kelp that can be incorporated into existing sea farms in Maine.

Objectives: This project seeks to:

Objective 1: Determine year-round growth rates of green sea urchins reared on farmed sugar kelp and wild set algae in sea cages at two different sea farm sites in Maine

Outcomes: Data will inform cultivation strategies and determine growth rates for urchin grow-out utilizing locally grown feed on sea farms in Maine

Objective 2: Develop year-round cultivation strategies for sugar kelp and wild set algae to be utilized as feed for sea urchins

Outcomes: Strategies for successful year-round production of sugar kelp and wild set algae to be utilized as environmentally sustainable urchin feed

Objective 3: Characterize unique farm seasonality to determine integration needs and opportunities

Outcomes: Farm management plans for oyster and seaweed farms in Maine to allow for successful urchin and kelp feed integration

Once the fastest growing marine fishery in the US, the Maine green sea urchin fishery is another “boom and bust” cautionary tale. While Maine has had a small urchin fishery since the 1930’s, the fishery rapidly expanded in the late 1980’s, peaked in 1993 at 41 million pounds, then declined to 2 million pounds in 2018 (DMR, 2018). Efforts at reseeding wild populations were unsuccessful due to high predation (Leland et al, 2001), and wild stocks have not recovered. The increasing demand for high quality uni (sea urchin gonads), global market of $400 million, and limited wild resource presents an opportunity for aquaculture, but urchin aquaculture represents less than 0.01% of worldwide production (James et al., 2017). While several research trials have been conducted on urchin culture in Maine, there has never been an attempt to integrate urchins into existing seaweed and shellfish farms. We propose to determine the commercial feasibility of raising urchins in conjunction with seaweed for feed on existing sea farms, creating essential baseline data for the development of commercial integration of urchins onto sea farms.

Maine has recently experienced an increase in seaweed and shellfish aquaculture leases, with the majority of farms cultivating only one crop. Marine aquaculture leases are the most valuable asset to any ocean farmer. In Maine, the lease process can take several years, and represents a comprehensive process that requires considerable investment. By integrating new species into a farm, farmers can increase sustainability, profitability, and resilience of a sea farm. Currently, there are only a few crop options for seafarmers, each presenting challenges. Seaweed crops lack sufficient processing and marketing infrastructure, and are very low value at the dock, and shellfish can be closed from red tide biotoxin events, and can take several years to reach market size in the cold waters of Maine.

Standard commercial aquaculture leases in Maine are divided into two categories; non-discharge and discharge. Non-discharge aquaculture includes seaweed and shellfish aquaculture, where organisms obtain all their food from the surrounding environment, requiring no additional inputs. Finfish aquaculture is discharge, introducing feed into the environment, requiring a pollutant discharge permit and additional oversight by the Department of Environmental Protection. Globally, efforts to cultivate sea urchins have included use of a pelleted feed, which is often made with fishmeal, which raises concerns about feed sustainability, nutrient loading in the environment, and off-flavors introduced through feed. To avoid the complications of the discharge category, eliminate the need for additional nutrient loading in the environment, and to build sustainability into the culture system, we propose to cultivate kelp as feed for the urchins on the sea farms in conjunction with urchins. By cultivating sugar kelp year round, the farms will generate sufficient amounts of feed for an urchin crop. It is expected that sugar kelp and sea urchins can be cultivated as a secondary crop on both seaweed and shellfish farms to enable economic and species diversification for farmers.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Experiments on urchin and kelp cultivation and seasonal farm integration took place on an oyster farm and a seaweed farm at two geographically distinct sea farms in Maine.

Winnegance Oyster Farm is located in the New Meadows River in West Bath in a highly protected inshore site with strong tidal exchange. The farm has a maximum high-tide depth of 30’ (deeper than most oyster farms in the area, which average 15’). Surface-water temperatures in the summer reach as high as 21°C, though deeper portions of the farm remain in the tolerance range of urchins during warmer months (measured high of 17°C in Aug 2019). The farm consists of floating oyster cages and lantern nets that are tended on the surface from early April until the beginning of December. Oyster cages are overwintered on the bottom during winter months to avoid ice damage. Quahog clams are grown in the sediments year-round.

Springtide Seaweed’s farm site, located in Sorrento, is a relatively exposed site, with a five mile fetch to the east and south. The farm lease is located in deep water, at 80-90 feet, and experiences high surface summer water temperatures of 18°C and low surface winter water temperatures of -1.7°C. Springtide cultivates several species of kelp on submerged horizontal long lines suspended with buoys and held in place with moorings. Kelp seeding takes place in the fall (September-November) and harvest in the spring (March-June).

Due to Covid-19 disruptions in the sea urchin hatchery schedule at CCAR (UMaine Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research), new seed urchins were not available at project start, so we utilized juvenile urchins (approximately 4 cm diameter) produced at the CCAR hatchery in 2019. Springtide had been rearing these juvenile urchins in indoor nursery tanks since July of 2019.

Objective 1:

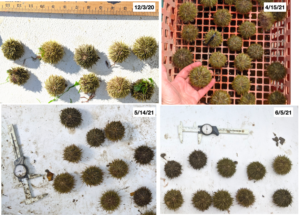

Grow out strategies for juvenile urchins: Year 1: both farms placed 100 juvenile urchins produced in the CCAR hatchery and reared in the Springtide nursery out on sea farms in the fall. Urchins were stocked at a density of 5-10 urchins per layer, photographed upon stocking, and monthly thereafter for analysis with ImageJ image processing program to determine growth rates by measuring test diameter. Urchin cages were stocked with available wild set algae and farmed sugar kelp.

Winnegance, an oyster farm, integrated urchins into existing oyster operations. In December, urchins were overwintered in bottom cages. Springtide Seaweed, a seaweed farm, suspended urchins in lantern nets from longlines year round.

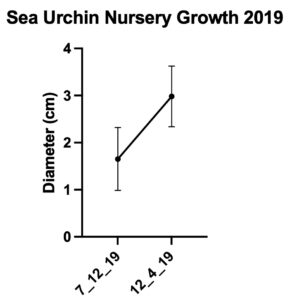

Sea Urchin Nursery

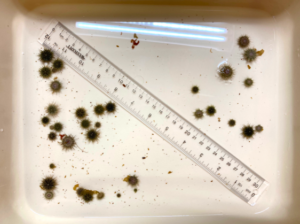

Sea urchins were obtained from the urchin hatchery at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Research, and reared in 4 foot diameter shallow round tanks at the Springtide Seaweed nursery. Newly settled sea urchins are less than 1 mm in diameter, and require a nursery phase before outplanting on the farm, until they reach a size that will allow them to remain inside the cultivation nets (>4-9 mm).

Springtide obtained several sets of hatched urchins, in July of 2019, and October of 2020, from the CCAR urchin hatchery. In July of 2021, Springtide received a sea urchin larval solution of pre-settled urchins to settle onto shell hash and macroalgae at the Springtide Seaweed nursery.

Sea urchins from the Springtide nursery were delivered to the Winnegance farm in November of 2020, and placed out on the Springtide farm in July of 2020.

Objective 2:

Sugar kelp, a natural macroalgal feed for urchins, was cultivated on both farms. Winnegance cultivated sugar kelp in the 2020-2021 season, and Springtide cultivated sugar kelp in the 2020-2021 and the 2021-2022 seasons. Horizontal submerged longlines were seeded with two different strains of sugar kelp (a downeast strain at the Springtide farm and a midcoast strain for the Winnegance farm). Kelp seed spools, consisting of 2 mm kelp juveniles attached to twine wrapped around a length of PVC pipe, were grown at Springtide’s seaweed nursery, and seeded onto horizontal long lines at each farm in the late fall. Kelp was deployed in November (Springtide farm) and in December (Winnegance Farm) for cultivation through the winter months for urchin feed.

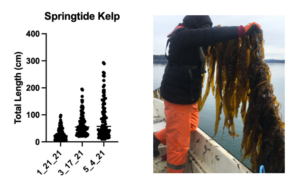

Springtide and Winnegance each seeded a dedicated kelp line for urchin feed, and attempted year round cultivation to determine feasibility of extending the growing season. Typically, kelp lines are taken in after harvest in the spring and farms are fallowed through summer months. Growth and health of plants was monitored through the season through measurements of sample plants, photographs, and observations.

Objective 3:

Each farm collected temperature and light data by affixing HOBO data loggers on an anchor line. Biofouling activity was monitored by noting species and abundance through the growing season. Farm activities were analyzed for urchin and algal integration and optimization. A report describing the optimal integration strategies for oyster and seaweed farms was created as a resource for the aquaculture industry.

Temperature

Winnegance - New Meadows, West Bath, ME

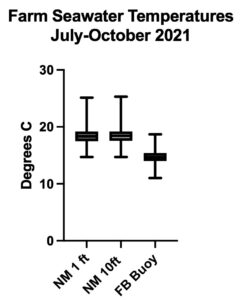

Previous data indicated that surface-water temperatures in the summer in the New Meadows River reached a high of 21°C, with deeper portions of the farm remaining in the tolerance range of urchins during warmer months (measured high of 17°C in Aug 2019). However, temperatures reached highs of 25°C (77°F) in July, with deeper temperatures at 10ft showing the same or slightly higher temperatures as the surface. There was a period of sustained temperatures of 20°C (68°F), even at 10 ft, through the months of July through September.

Winnegance - New Meadows, West Bath, ME

Previous data indicated that surface-water temperatures in the summer in the New Meadows River reached a high of 21°C, with deeper portions of the farm remaining in the tolerance range of urchins during warmer months (measured high of 17°C in Aug 2019). However, temperatures reached highs of 25°C (77°F) in July, with deeper temperatures at 10ft showing the same or slightly higher temperatures as the surface. There was a period of sustained temperatures of 20°C (68°F), even at 10 ft, through the months of July through September.

Springtide - Frenchman Bay, Sorrento, ME

Hobo pendants deployed by Springtide on lantern nets failed with leakage of seawater. Instead, temperature data was collected by the nearby buoy in Bar Harbor. Max temperatures of 18.7°C were reached on 8/15/2021. Minimum temperatures of -0.7°C occurred in March. Temperatures over 16°C only occurred in the last two days of June, and through July-September.

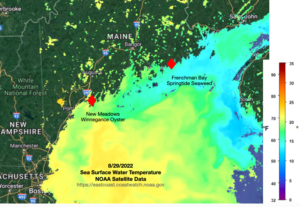

Satellite sea surface temperatures from August of 2022 indicate a north-south difference in summer temperatures in the Gulf of Maine, with Penobscot Bay dividing the Gulf into warmer waters to the south into temperatures 20°C and above, and cooler temperatures to the north in the 15-20°C range. Green sea urchins are a cold water species, with upper critical limits for benthic stages at 20°C, so it is unlikely that sea urchin cultivation will be successful from Penobscot Bay south.

Sea Urchin Cultivation

Winnegance-New Meadows River

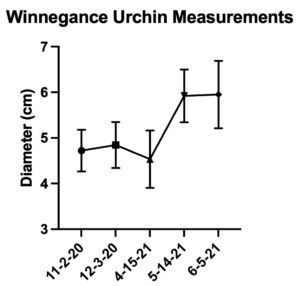

Sea urchins were brought up from overwintering cages in the spring and placed in lantern nets with seaweed, with 100% survival. Sea urchins measured in November of 2020 had an average diameter of 4.7 cm, and increased in average size to 5.95 cm by June of 2021, an increase of 26% over 6 months. All urchins appeared healthy through June, but then the urchins experienced a major mortality event.

Hands on urchin measurements were suspended in July on the advice of a technical advisor in order to avoid heat shock. Urchins were observed quickly during feedings to check for mortality. Mortality was not observed until September 30. At this check, 95% of urchins were lost. There were several potentially interacting sources of mortality- prolonged heat stress, rapid fouling that trapped waste and decomposing kelp in lanterns nets (smothering), and an unusual influx of fresh water. The surviving urchins were all in top tiers of lantern nets, in the warmest water (~1.5 m deep) and with the least decomposing kelp- which suggests temperature stress was not the only culprit. These urchins died after a second major rain event in mid October.

Springtide - Frenchman Bay

Urchins on farm were periodically checked, photographed, and fed, with 100% survival. In the fall of 2021, lantern nets became tangled and submerged around a mooring line, and were recovered several months later with very high survival, despite holes in the nets and heavy mussel sets. Lantern nets were prone to fouling by skeleton shrimp, tunicate, mussel seed sets, and starfish, and need to be changed at least once or twice a year. Even when not fed intentionally, urchins survived in cages by grazing wild food, and by eating small mussels. Although there were also eventually starfish present in the nets, it appeared that they were feeding on the blue mussel seed set, and did not consume the sea urchins.

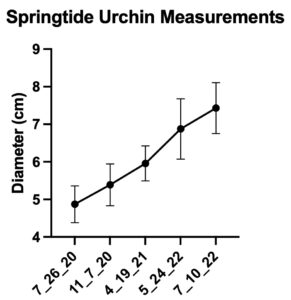

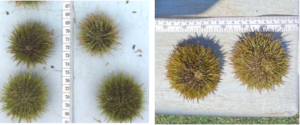

The juvenile “seed” used was larger than what might be utilized from an urchin hatchery, since the urchins had been cultivated for about a year in nursery tanks at Springtide Seaweed. The larger juvenile individuals (4.8cm diameter) placed out in nets grew 2.6cm over 2 years, reaching diameters of 7.94 cm (max 9cm), which are over the harvestable size limit of 2 inches (5.08 cm).

Sea Urchin Nursery and Hatchery

Sea urchins were obtained from the urchin hatchery at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Research, and reared in 4 foot diameter shallow round tanks at the Springtide Seaweed nursery. Newly settled sea urchins are less than 1 mm in diameter, and require a nursery phase before outplanting on the farm, until they reach a size that will allow them to remain inside the cultivation nets (>4-9 mm).

Springtide obtained several batches of hatched urchins, in July of 2019, and October of 2020, from the CCAR urchin hatchery. In July of 2021, Springtide received a sea urchin larval solution of pre-settled urchins to settle onto shell hash and macroalgae at the Springtide Seaweed nursery. Larval settlement, metamorphosis, and growth was successful in the Springtide settling tanks, producing over 1000 juveniles that reached 12mm in 7 months. In early 2022, Springtide successfully hatched a complete batch of juvenile urchins at their nursery, from fertilization, larval stages, metamorphosis, and juvenile development. The additional sea urchin nursery work was supported by a Northeast SARE Farmer Grant FNE21-992, but was integrated with this project, as we work towards building a better understanding of the hatchery, nursery, and farming process.

Sea urchins are fed a mixed diet of kelp, dulse, nori, and sea lettuce in the rearing tanks, with aeration, temperature control, and water changes weekly. In 2019, the seed obtained from the CCAR nursery grew an average of 1.329 in 5 months. This seed had already spent some time developing in the CCAR hatchery before coming to Springtide. With current ongoing experiments, it seems likely that urchin seed could be placed out on the farm in about 8-10 months, and harvestable urchin could be cultivated within 3 years.

Kelp Cultivation

Winnegance

Winnegance Oyster Farm conducted several surveys of the local coastal area for wild populations of sugar kelp for sorus tissue collection in August, September, October, and November, but was unable to find any sufficient for seeding. The kelp spool obtained from the Springtide nursery was hung on the farm until December 3rd 2020, when the long line was installed and seeded. In spring of 2021, Winnegance oyster farm had a full, healthy line of kelp. Kelp was sampled in May and June and monitored through the summer. After June, kelp deteriorated rapidly, and hosted increasing growth of biofouling organisms.

Kelp was only a reliable food source for urchins until mid August, after which saw the rapid breakdown of blades and fouling of ropes and remaining stipe. Though a small amount of stipe tissue was present until the end of the season (Nov. 30), results point to the vulnerability of relying on a single species for urchin feed- with a potential gap in food availability from August until a new winter kelp crop. Wild set kelp persisted in surface waters on oyster cage throughout 2021. This kelp remained small (total length <24”) but did not foul or decompose despite spending the entire season in warmer water than the cultivated kelp.

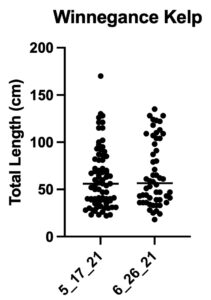

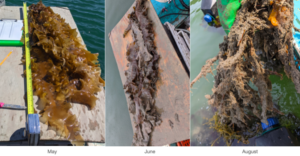

Springtide

Springtide seeded a local strain of sugar kelp onto the farm in the fall, and took 10cm samples across the line for total length measurements. Kelp grew to max lengths of 293cm by May, and plants were clean and healthy. By July, plants start to accumulate biofouling organisms (hydroids, bryozoans, skeleton shrimp), and this fouling continues to increase through the summer with the spread of bryozoans and skeleton shrimp, and the mussel seed that sets on plants and lines. By September, remaining plants are mostly covered with the encrusting bryozoan and are in poor condition. However, new growth begins again in August, and some clean kelp tissue can be found at the base of the blades. The high amount of biofouling adds strain and weight to lines, and should be avoided by removing all plants and lines by August. There are usually wild kelp plants that float through the farm, which can serve as a high value feed for the urchins during the summer months. Urchins can also survive by grazing the biofouling organisms that grow in the lantern nets, and by feeding on the small mussel seed that land in the nets.

Biofouling

Winnegance

Fouling in 2020 and 2021 was unusually heavy and did not follow prior patterns seen from 2014-2019. Unlike those years, where tunicate and sea vase fouling occurred in a single wave starting in late July and continuing through Aug, the last two seasons saw multiple “sets” of tunicates all the way into October. It is unclear how much this heavy fouling played a role in the loss of kelp. There is also potential that the fallow kelp line served as a reservoir for tunicates- as oyster cages on the line above were much more heavily fouled than cages on other longlines with the same air drying regimen. If this were a consistent effect, it would be a major drawback for farmers hoping to add this polyculture system to an existing farm.

Springtide

The major biofouling organisms on lantern nets include diatoms in the winter and early spring, and skeleton shrimp, hydroids, mussels, tunicates, red filamentous algae, and sea stars in the summer months. Biofouling reduces water flow through the nets, and greatly increases the weight on the long line. Cages should be changed out once or twice a year to avoid biofouling impacts.

Winnegance

The variable nature of the oyster site (extreme temperatures and salinity fluctuations) resulted in sea urchin mortality. Although kelp was a successful crop on this farm, it was only viable through May, as it quickly fouled and began to decay and host invasive species. Sea urchins are probably not going to be a viable crop on oyster farms, unless sited in cooler, deeper waters away from major freshwater runoff.

Springtide

Both kelp and urchins are viable co-crops on deep water, cold ocean sites. While kelp is abundant from February through July on the lines, there is a lack of feed source for the urchins from August through January. Sea urchins can survive by grazing on wild algae and mussel seed that settle inside the lantern nets, but major fouling on the nets can be a problem for water motion, and cages should be changed out at least once per year to avoid biofouling build up. Sea urchin cultivation is easily integrated into a cold water seaweed farm, and requires minimal time investment. Further work is required to develop high value markets for Maine farmed sea urchins to create a business plan for further commercialization. There is also great potential for breeding work, to select for faster growing individuals, for unique characteristics, and for uniform size. Macroalgal feeding trials will also be useful for roe enhancement and unique high quality flavor profiles.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

The Maine Seaweed Exchange and partner farmers shared project activities and updates through visits to the Springtide farm and facility, social media postings of progress, and classes. The Maine Seaweed Exchange will create a special page on their website describing the project and offering resources for growers. Interested audiences include the general public, aquaculture farmers, chefs and restaurants, and potential new sea farmers.

The Maine Seaweed Exchange is compiling sea urchin aquaculture resources to share on the web, as well as to include in future aquaculture classes, trainings, and workshops. The results obtained from this and other recent sea urchin cultivation and market work will better inform outreach and education to the public. Given the results of this project, sea urchin aquaculture will need to be further developed for markets, and systems tailored toward the colder Downeast region, so the MSE is restructuring their approach to the outreach.

Several educational talks were given in 2021 by Sarah Redmond (and Andrea Angera, through the Maine Seaweed Exchange) to a wide range of audiences. Although the talks focus mainly on seaweed aquaculture, we include diversification information, including the work we are doing with sea urchins.

Zoom talks:

Friends of Taunton Bay Webinar Series, “Seaweed Farming with Sarah Redmond”

6/7/21 The Friends of Harriet L Hartley Conservation Area, “Seaweed Aquaculture in Maine”

8/18/21 Monhegan Associates, “Seaweed Aquaculture in Maine"

In Person Presentation:

9/16/21 The Pour Farm, “Seaweed Farming in Maine”

7/2022: Gouldsboro Historical Society, Organic Seaweed Farming in Maine

Maine Seaweed Exchange online Trainings:

1-day Seaweed Aquaculture Intensive, by Sarah Redmond and Andrea Angera

Dates:

1/16/21

5/22/21

9/11/21

5/23/22

Outreach through Visits and Field Trips to Springtide Seaweed nursery and farms

10/2021 Field Trip for marine biology students from University of Maine

7/2022 Visit by Governor Mills and community members

7/2022 Visit by representative from US Congress

Trainings, Internships, Work Experiences

2020-2021: 5 Interns

2021-2022: 5 Interns

A report describing the optimal integration strategies for oyster and seaweed farms was created as a resource for the aquaculture industry. MSE-Urchin-Resource

Learning Outcomes

Gaining better understanding of the opportunities and limitations in cultivating sea urchins on different types of farm sites.

Project Outcomes

This project has given us a better understanding of how and where sea urchins can be integrated into existing sea farms.

This project gave us great insight into the requirements and challenges of integrating sea urchins into existing aquaculture operations. From these results, we can recommend further work for cold water sites, and can design new types of cultivation gear and strategies to address the biofouling issues that lantern nets have. This work will inform further work and allows us to move into the next phase of development, which will include harvest, handling, and marketing of the farmed sea urchins.