Final report for ONE22-416

Project Information

Johne’s disease is an infectious disease common within the dairy industry caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). Johne’s disease has a negative economic impact on dairy herds due to milk production loss, premature culling, and reduced cull values. This study partnered with eight dairy farms in Vermont to understand the decision-making process around culling early lactation animals as a means to control Johne’s disease within their herds and improve economic viability. In order to support the decision-making process, diagnostic testing of individual animals was provided along with an economic analysis. This information was used to understand how producers make a culling decision and what types of information are important to that decision. A focus group with partner farms was conducted to further understand the concern regarding Johne’s disease and perceived barriers to implementing recommended management changes. Results from this study show that low production in early lactation is not predominantly caused by Johne’s disease, but likely due to a variety of factors. An updated set of fact sheets were created to further share knowledge and best management practices related to Johne’s disease with dairy producers and service providers.

- To determine whether partner farms would be willing to use early lactation culling as a management strategy to control Johne’s disease within their herd.

- To understand the role of providing certain information to support the early lactation culling decisions of partner farms.

- To facilitate peer to peer learning through a focus group with partner farms designed to understand concern related to Johne's disease and barriers to implementing management practices. Updated fact sheets based on findings from this study were created as an outreach material to both dairy farmers and service providers to provide education about Johne's disease.

Johne’s disease is an infectious disease common within the dairy industry caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). Johne’s disease is a significant challenge for both animals and producers as it leads to milk production loss, premature culling, and reduced slaughter values. It has been estimated that over 60% of the nation's dairy herds are infected with Johne's disease at some level (Barkema, 2018). The economic impact of Johne's disease within the dairy industry in the United States is estimated to be approximately $200 million annually (Rasmussen, 2021). It can be difficult to truly assess the cost of Johne’s disease on a per cow or herd level basis since the costs of the disease are indirect in the form of lost milk production, poor reproduction, and premature culling from the herd. However, a recent study estimated that the per cow revenue loss is $33 USD per year for herds infected with Johne’s disease (Rasmussen, 2021). This seems like a relatively small and innocuous number, but these losses equate to roughly 1% of a herd’s total milk revenue per year. In an industry that operates on increasingly small margins, the ability to increase farm revenue by even 1% can have a significant impact on a farm’s overall economic sustainability.

Johne’s disease can be difficult to diagnose, as it is only when an animal starts to shed a high enough level of MAP bacteria that infection can be accurately detected by diagnostic tests. Testing and culling animals with a positive result has been used as a method for reducing the spread of Johne’s disease within a herd. This can be a problematic control method due to the potential for error in test results. Additionally, most farms find it cost-prohibitive to routinely test animals. While much of the research has been focused on reducing the spread of Johne’s disease through testing and other management improvements, there is a lack of research that looks at how milk production is impacted by the disease. A promising approach to understanding how Johne’s disease affects milk production was published in 2008 by Smith et al., but the applications of their findings have yet to be fully explored. By using milk production data already collected by the farm, our study looked at decision making regarding culling animals within the first 90 days of lactation. In partnership with local dairy farms, we used milk production data to identify cows for removal from the herd based on poor performance, which may be an indicator of infection with Johne’s disease. In any case, these animals may have a negative economic impact on the farm. In order to support the farm’s decision-making process surrounding culling animals in early lactation, we tested low producing animals for Johne’s disease. We also analyzed the economic impact surrounding culling these low production animals from the herd.

In keeping with the desired outcomes of SARE, this project aims to improve animal health and economic sustainability of our partner farms, which represent a diverse spectrum of dairy production styles, including conventional and organic farms. Our proposed outcome would show that culling low producing animals in the early stages of their lactation is both an effective means to control Johne’s disease within a herd, as well as have a positive economic benefit to overall farm profitability. We hope to encourage other farms to adopt our management practices surrounding culling, so we also seek to understand how different farmers are motivated to change their behaviors. Successful adoption of the new culling strategy by partner farms would suggest our results will be widely applicable to all types of dairy farms.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Technical Advisor (Educator)

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Recruitment and survey

Nine farms, six conventional and three organic dairies, participated in this study. Farms were recruited with the help of local veterinarians. Upon enrollment in the study, farms were surveyed to understand their current perceptions of Johne’s disease presence on their farm, as well as management strategies related to disease control. The survey consisted of 16 questions, made up of 9 multiple choice and 7 short answer questions divided into three areas of interest: 1) concern surrounding Johne’s disease; 2) motivations related to management decisions; 3) likelihood of adopting a new culling strategy to manage Johne’s disease. Farmer responses were assigned a number to maintain anonymity.

Environmental Samples

Environmental fecal samples were collected from each farm to determine herd prevalence of Johne’s disease. A total of 54 samples representing nine farms were taken from six high-traffic areas on each farm, including walkways, pens, manure collection areas, and calving pens. These samples were sent to the Animal Health Diagnostic Lab at Cornell University for fecal culture.

Individual Samples

Individual fecal PCR tests were allotted to partner farms based on the number of calvings expected within a 12-month period. The number of partner farms decreased from 9 to 8 following initial environmental sampling due to one farm selling their cows. A total of 442 individual samples were taken from 8 participating partner farms. Prior to beginning individual sampling on partner farms, it was necessary to determine how cows would be identified and selected for sampling. Based on the variation in farm size and management style among participating farms, it became clear that there was not a single method to determine which animals would be selected for individual sampling that could be applied across all farms. We worked with each farm to establish criteria for selecting animals for individual testing. For herds on monthly DHIA test, test day milk production data was used to identify cows under 100 DIM that showed a decrease of 10 pounds or greater from their previous monthly production to be selected for testing. For herds using daily milk production data collected from the parlor, animals under 100 DIM that showed a decline in production for more than 7 days were selected for testing. These criteria were combined with producer input based on animals determined to not be producing as expected in the first 100 days of lactation or were observed to have clinical signs of disease, such as excessive loss of body condition or watery manure. Animals that fell within these criteria were selected for individual sampling for Johne’s disease. A fecal sample was collected from the animal and sent to the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Lab for a fecal PCR.

Follow-up after individual testing-culling

In order to determine whether animals selected for individual sampling should be considered for removal from the herd, three key pieces of information were provided to partner farms. First, results from the fecal PCR were provided showing the animal’s Johne’s disease status. There are five possible test result outcomes of a fecal PCR test; high shedder, moderate shedder, low shedder, negative, and suspect. A suspect test result indicates that either the sample may have been contaminated or the result was a very low positive. The second piece of information that was provided to partner farms was current milk production and stage of lactation. Finally, an economic analysis (The Economic Value of a Dairy Cow from UW-Madison Dairy Science) showed the profitability of a cow compared to herdmates was provided. Animals classified as heavy shedders were advised to be removed from the herd immediately to prevent further spread of Johne’s disease. Animals with a moderate, light, negative, or suspect test result were not advised to be removed from the herd based solely on test status. Milk production, age of the animal, and days in milk (DIM) were entered into the economic analysis tool, and those animals with a significantly negative economic contribution were recommended for culling consideration.

Farmer focus group

A farmer focus group was conducted with three of the participating partner farms in March of 2024. Focus group participation was optional and open to all eight farms that participated in this study. Participants were paid a stipend for their time and expertise. The focus group was approximately two hours in length and was audio recorded and transcribed to facilitate analysis. A trained researcher was present to take written notes summarizing the discussion and key points. Five primary questions were asked, with additional probes to gain further detail and understanding. Questions were intended to understand general thoughts and concern about Johne’s disease, their perceived barriers to adopting management recommendations, and culling practices on their operations.

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the transcripts to identify key themes. The same researcher that was present during the focus group used the transcript and notes to code and categorize themes by content area.

Johne’s fact sheets

As a method to share knowledge surrounding Johne’s disease with a wide audience, a set of fact sheets was created. The goal of these fact sheets was to provide an understanding of how Johne’s disease can infect an animal or herd, how the disease progresses, and management strategies to reduce risk.

Survey Results

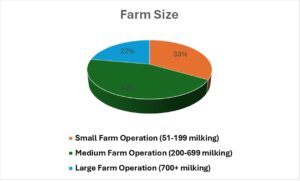

Nine farms completed the survey. Respondents were comprised of 33% certified small farm operations (51-199 milking animals), 44% medium farm operations (200-699 milking animals), and 22% large farm operations (milking greater than 700 animals).

Figure 1: Partner farms represented by number of milking cows.

Figure 1: Partner farms represented by number of milking cows.

Responses to the question ‘What is your level of concern regarding Johne’s disease on your farm?’ ranged from a little to moderate. Four of the nine herds had previously participated in a nationally funded program called VTCHIP that provided testing and veterinary services to help farms reduce Johne’s disease, so many of the participating farms had knowledge of Johne’s disease and diagnostic testing. Concerns related to the economic impact of Johne’s disease on the farm ranged from not at all concerned to extremely concerned. More than half of the respondents did not know whether Johne’s disease was present on their farm, or they were not culling cows exhibiting clinical signs which led to less concern about the economic impacts of the disease. Two participants had previous experience with the negative economic impacts of Johne’s disease in their herds, and had personal experience with how devastating the disease can be. All farms were implementing some type of Johne’s disease control methods, even if they did not initially recognize management practices as such. All respondents indicated that livestock health was very important when making management decisions. Economic impact when making management decisions was ranked as very important by 78% of participants, with the remaining 22% ranking it as somewhat important.

When asked about details for culling animals, primary reasons included feet and legs, reproductive status, low production, and somatic cell count. Responses to the question of how likely they would be to implement a culling strategy to help reduce Johne’s disease on farm were varied, but participants would be more likely to cull animals that had a positive test result. This response was further supported by a follow up question that asked participants to select the practices they thought were acceptable for managing Johne’s disease on their farm. 67% of participants would cull if individual test results suggested they do so, while 11% would cull if economic impacts suggested they do so, and 22% would cull if test results, production records, and economic impact suggested they do so.

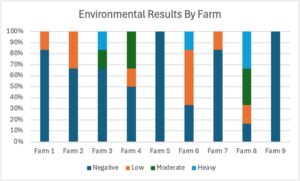

Environmental Results

Results from the environmental samples taken from each farm are represented in Figure 2. The majority of the samples were negative, which indicates that the herd prevalence is likely very low with no animals in the clinical stage of Johne’s disease. For the samples that had a light, moderate, or heavy result, this indicates that there is some level of infection present within the herd. Due to the largely subclinical nature of Johne’s disease, there is the potential for a small number of animals shedding millions of bacteria into the environment. Samples classified as heavy could be due to one or more “super-shedders” in the herd contributing heavily to the environment.

Figure 2: Results from Environmental Fecal Culture Samples from Nine Farms

Figure 2: Results from Environmental Fecal Culture Samples from Nine Farms

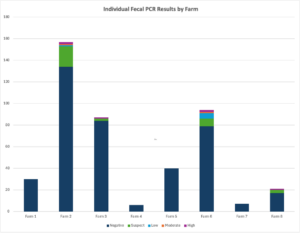

Individual Sample Results and Economic Analysis

A total of 442 individual fecal samples were analyzed for detection of Johne’s disease across the eight partner farms. Results by farm are detailed in Figure 3. Of the 442 samples analyzed, 89.8% of the individual samples were negative, 7.0% were suspect, 1.3% were identified as low shedders, 0.5% were moderate shedders, and 1.3% were heavy shedders. These results did not support our initial hypothesis that cows with low milk production in early lactation could be infected with Johne’s disease and shedding detectable levels of the bacteria. However, the high proportion of negative results could indicate that many farms have successful management practices in place that have reduced their herd prevalence of Johne’s disease.

Figure 3: Individual Johne’s disease test results by farm

Figure 3: Individual Johne’s disease test results by farm

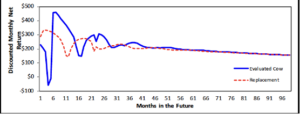

Along with the individual test results, each farm received an economic analysis for each cow tested for Johne's disease. The economic analysis tool utilized a series of inputs based on each individual herd's metrics and compared the cow to her herdmates and gives the animal an economic value compared to a replacement animal. This supporting piece of information was provided as additional support to farms for consideration of culling a cow in early lactation if her test result was positive and her economic contribution to the herd was negative. Johne’s test status, milk production, and profitability were provided as supporting evidence that culling an early lactation animal could have a beneficial impact on their herd, both from a disease management and financial standpoint. This economic analysis tool was useful and informed conversations around management and culling decisions with partner farms. Based on individual test results and economic analyses provided, partner farms were willing to cull an animal classified as a "high shedder" in early lactation but were resistant to cull moderate or low shedders, even when the economic analysis indicated they should do so. This was likely due to these animals being early lactation, and partner farms were reluctant to cull animals in early lactation without multiple reasons. This was especially true if animals producing poorly in early lactation were 1st or 2nd lactation animals, as the return on investment has not been achieved for that animal and her potential for production in future lactations high.

Farmer Focus Groups

A total of four dairy producers, 3 male and 1 female, from three of the participating partner farms attended the focus group. Herd sizes ranged from 200 to 700 cows. All three farms that participated in the focus group had at least one test-positive cow during the course of the study.

During the qualitative analysis, two themes emerged: (1) knowledge of Johne’s disease and management practices and (2) financial impacts of management recommendations.

Theme 1: Knowledge of Johne’s Disease and Management Practices

One subtheme related to farmer knowledge and management practices surrounding Johne’s disease was identified. A decrease in farmer concern related to Johne’s disease on their own farms was identified among all participants. One participant responded, “we know the disease is endemic in our herd, but we have implemented management practices that allow us to keep it in check.” Participants were aware of Johne’s disease and the impact it can have on the farm, but through increased awareness of the disease and education about best management practices they felt they had the necessary tools to manage the disease.

Participants also expressed a decreased concern regarding Johne’s disease in the dairy industry as a whole. The consensus was that Johne's disease is less prevalent in herds now than it was nearly 20 years ago and therefore less of a threat to the industry. However, all participants agreed that if a definitive link between Johne’s disease in cows and Crohn’s disease in humans were ever proven, it would become a huge concern throughout the dairy industry.

Producer responses around animal health concerns showed that other diseases or health concerns were of greater concern as compared to Johne’s disease. Two of the three farms acknowledged that Johne’s disease ranked in the top 5 concerns related to health issues within their herd, while one producer indicated that Johne’s disease was only considered when there was no other apparent reason for illness in a sick animal.

Theme 2: Financial Impacts of Management Recommendations

Two subthemes related to financial impacts of management recommendations were identified during analysis. First, the cost of recommended management changes was identified as a barrier to implementing changes. Infrastructure upgrades to improve management are a commonly identified need among dairy farmers in Vermont to improve or alleviate management concerns such as overcrowding or to reduce the spread of disease. The financial investment needed to implement these recommendations is often perceived as too large of a barrier to overcome for many dairy farms. Participants highlighted the need for recommendations that require significant financial investments to show a return on investment and how improvements would lead to increased financial viability for the farm. One participant commented, “Don’t show me what I can gain by implementing something today, show me how much money I've lost because I didn’t do this five years ago.”

Financial incentives provided to farmers were also identified as a potential way to overcome the barriers to implementing management changes on farms. Participants identified programs within the dairy industry currently in place that provide financial incentives, such as milk quality premiums and grant funds. However, these incentives are not equitable across all farms, with participants identifying the challenging process of applying for and obtaining grant funds that would reduce the financial burden of implementing new practices on the farm. One potential incentive program that gained unanimous support among the participants was for premiums paid directly to producers to certify that their milk was “Johne’s free” if such a program were to be put in place.

Johne’s Fact Sheets

Fact sheets are attached to this report as an information product.

Discussion

The survey conducted with partner farms at the beginning of this study identified key motivating factors for both management and culling decisions. A key motivation for decision-making and culling was identified to be driven by overall economic impact to the farm. However, when farms were presented with follow-up information following individual testing which included current milk production and an economic analysis, very few farms were willing to cull an animal in early lactation despite low milk production and a negative economic contribution to the herd.

Environmental results highlighted that while a herd may not have individual animals that yield a positive test result, there can still be a detectable level of Johne’s disease on a farm. Because of the largely subclinical nature of this disease, many animals that may be infected are not shedding detectable levels of the bacteria; it is possible for the MAP bacteria to be present in the environment but not yet detectable by fecal PCR tests in individual animals. The environmental samples were analyzed via fecal culture, which is the most sensitive and accurate test for detecting Johne’s disease. The downside to this test is that it is more expensive, and results take between six and eight weeks, which make it an impractical choice for individual testing. Most infected herds have a low within-herd prevalence with roughly 30-40% of infected cows shedding the bacterium (Barkema et al., 2010). This further supports a need for educational resources provided to producers that highlight Johne’s disease as an animal health concern and the need for continued management practices that can help reduce the risk of disease in a herd.

The initial plan to develop a singular approach to identify individual animals for sampling was modified from the original proposal. In the initial stages of developing cut points for production for each farm, it became obvious that due to the different management styles and methods used to manage data on partner farms that cut points determined without producer input would not be a viable method for selecting individual cows for sampling. In addition, the originally proposed method of cut points based on production would not be easily adopted by farms. Instead, criteria for individual sampling were developed using current milk production, change in milk production over time, and producer input. We felt this approach was a more realistic expectation for farms that may adopt this method after the study.

The individual samples yielded results that were unexpected. The working hypothesis for this study was that the significant stress calving places on a cow would cause her immune system to be weakened and if a cow were infected with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), detectable levels of MAP would be present during early lactation. However, individual samples yielded largely negative results. Upon reflection, it seems likely that calving could be the event that precipitates a previously infected animal to progress from the silent stage of infection to the subclinical stage, and that animal may not begin to shed detectable levels of MAP until later in lactation. Throughout the process of identifying and sampling individual cows, it became apparent that many different factors can influence milk production in early lactation or a decrease in production between monthly milk tests. As is common when conducting research on working dairies, there are many confounding variables that can account for variation in milk production. Some examples of these variables are putting cows out on pasture in the spring, group changes, forage and diet changes, and illness. These examples were more apparent in herds that utilized monthly milk testing compared to herds that had daily milk weights from the parlor.

Follow-up visits with partner farms to present results of individual samples and economic analyses highlighted reluctance to cull early lactation animals. It was expected that farms would be hesitant to cull an animal in early lactation, which was why this study provided three pieces of information as evidence for why a cow was a good candidate for removal from the herd. Farms were generally willing to cull an animal that had a test result indicating they were shedding a high level of MAP into the environment. Only 1.3% of test results were returned as high shedders, and this accounted for a very small number of cows, roughly 1 high shedder for every 75 cows tested. This number sounds innocuous, however a small percentage of cows in a herd diagnosed as high shedders can be responsible for shedding billions of bacteria into the environment and pose a substantial risk of spreading infection to other animals in the herd. The animals selected for individual testing were animals that showed a decrease in production or clinical signs of disease. However, not all animals shedding MAP bacteria have begun to exhibit clinical signs such as decreased milk production or excessive loss of body condition. It is likely that these animals selected for sampling that returned a high shedder test result would not have been identified and removed from the herd until they began to exhibit clinical signs, at which point other animals could have become infected. Individual testing can be useful to identify infected animals before they exhibit clinical signs, but the cost and time associated with collecting the samples have led many farmers to move away from preventive diagnostic testing once it was no longer subsidized. One potential way to address the concern of Johne’s disease prevalence on dairy farms is by conducting routine environmental sampling of the herd, which can help determine if there are heavy shedders present in the herd.

While the economic analysis tool utilized was designed to highlight the economic value of an individual cow compared to a replacement, it was found that significant drivers of this tool were milk production, days in milk, lactation number, and pregnancy status. The price of replacement animals also increased significantly during this study, which favored a more positive economic value for evaluated cows compared to a replacement. This increase in replacement animal cost may have placed a higher value on keeping marginal animals versus culling. Johne’s test status, milk production, and profitability were provided as supporting evidence that culling an early lactation animal could have a beneficial impact on the herd, both from a disease management and financial standpoint. However, these results highlight the need for a more in-depth financial analysis tool that could take into account the economic impact of Johne’s disease.

Figure 4: Example economic analysis graph of a cow.

Figure 4: Example economic analysis graph of a cow.

The focus group allowed for more in-depth discussions with partner farms surrounding Johne’s disease and their perceived barriers to implementing management changes. It was not surprising that Johne’s disease was not viewed as a primary concern on participating farms. Individual test results yielded few positive results, and farms had implemented management strategies designed to reduce the risk of infection. An unexpected finding from this focus group was the need for increased facilitation of peer-to-peer learning for dairy farmers. All focus group participants acknowledged that farmers are more likely to implement a new management strategy if they can talk directly to someone that has already done it. During the pandemic there were decreased opportunities for farmers to gather in person to allow for peer-to-peer learning to take place, and these gatherings have been slow to reestablish in recent years. There is an opportunity to provide more in-person opportunities for farmers to gather and share knowledge, particularly in the Northeast where dairy farm numbers are in decline.

The original fact sheets on Johne’s disease were created in 2009 by Dr. Julie Smith and Rebecca Calder at the University of Vermont. While much of what is known about how Johne’s disease infects an animal and the progression of the disease, there have been updates regarding how the disease is managed in the industry. A significant amount of focus was placed on testing individual animals and culling moderate and high shedders to help identify and remove infected animals from the herd. However, at the time there was support to help defray the cost of testing and veterinary services to encourage farms to implement the test and cull method. Since the end of this program, the test and cull method is no longer the gold standard. More focus has been placed on prevention through management practices. The updated set of fact sheets created will further support education of farmers and service providers, as well as provide veterinarians with a resource to educate their clients.

A primary limitation of this study was that it was a convenience sample. Many of the participating farms had previously participated in a voluntary Johne’s control program, and therefore had knowledge and experience with the disease. Local veterinarians were used for recruitment, which may have created a potential for bias of herds that veterinarians were concerned were at risk for Johne’s disease. An additional limitation of this study was the small size of farms recruited, with nine farms initially enrolling in the study and a final number of eight farms. This sample size may not be representative of the presence of Johne’s disease on Vermont dairy farms. However, conducting research on working dairy farms and coordinating times to sample cows takes time and effort, and a larger sample size was not feasible given the time and budget constraints of this project. It is possible that were this study conducted in a herd that had a high prevalence of Johne’s disease this culling strategy would be an effective means to control Johne’s disease. However, future studies that target later lactation cows with a sustained decrease in production may be a more practical means to identify and remove positive animals from the herd. While this study did not yield the expected results, further research into the economic impact of Johne’s disease would provide additional support for culling animals with positive test results. The results of this study highlight that the work to educate Vermont dairy farmers during the early 2000’s on the risks and impacts of Johne’s disease were largely successful. Dairy farmers now understand how to identify a cow showing clinical signs of disease, management practices to reduce the risk of introducing Johne’s disease into the herd, and this study was able to further support that these efforts had an impact through individual testing of cows.

This project sought to understand the willingness of dairy farms to cull early lactation animals as a management strategy to control Johne's disease within their herd. Additionally, this study explored the motivations that guide farms to implement a management change through peer-to-peer learning in a focus group setting. Individual cows were sampled to determine Johne’s disease status, and an economic analysis was provided to help inform management decisions. We found a detectable level of Johne’s disease on 78% of participating farms through environmental sampling, yet the level of individual samples that tested positive was low at 3.1%. Our findings showed that without a positive test result, farms were not willing to cull early lactation animals, even if milk production records and a negative economic contribution to the herd suggested they should do so. This project highlights that while Johne’s disease is still present on Vermont dairy farms, an increase in awareness of Johne’s disease and improvement in disease management on dairy farms in Vermont is in place since the conclusion of the government subsidized Johne’s control program.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

The 8 farms that participated in this study were provided Johne's disease diagnostic testing for individual animals in their herd, as well as follow-up visits to discuss economic impact of sampled animals. A focus group that was open to participants in this study occurred in March of 2024 and allowed participants to discuss impacts of Johne's disease and barriers to implementing management changes with their peers.

Future plans for communicating this work include a journal article in a peer-reviewed publication.

Johne's Disease Fact Sheets

A set of 12 fact sheets that are designed to be utilized by dairy producers, veterinarians, agricultural service providers, and educators to gain an understanding of how Johne's disease infects animals, disease progression, and management strategies to reduce disease presence. These fact sheets are housed on UVM Extension's Dairy Herd Management website.https://www.uvm.edu/extension/agriculture/johnes-disease

Manure Expo

On July 17, 2024, Whitney Hull, gave a guest lecture at the 2024 Manure Expo in Auburn, New York entitled 'Why You Should Care About Johne's Disease'. There were over 40 attendees to this lecture, which was one of four sessions occurring in the time slot. The Manure Expo draws a large attendance each year from across North America, and this lecture was an opportunity to share Johne's disease awareness and research with a broad audience.

The final report and a link to the factsheet will be posted at the University of Vermont Dairy Herd Management page when complete.

Learning Outcomes

While there was not a program evaluation performed with participants, all partner farms gained knowledge about Johne's disease specific to their farm. Each farm received an environmental screening, which provided information regarding the presence of Johne’s disease on their farm. Each farm also received diagnostic testing of individual animals, as well as follow-up visits that provided an economic analysis of each cow sampled.

All farms that participated in this project had knowledge of Johne’s disease prior to enrollment in this study, with some having firsthand experience with the disease and others having no experience with the disease on their operation. All participants were provided one-on-one technical assistance and education throughout this project.

Project Outcomes

Farmers participating in this study received environmental herd screening as well as individual testing for Johne’s disease on their farm. None of the farms were regularly testing animals for Johne’s disease at the time of enrollment in this study. As a result of this project, farms were able to better understand how milk production can play a role in Johne’s disease detection.

Two farms that previously did not perceive Johne's disease to be a concern had animals that returned a high shedder test result. Based on the education that they received through the study, both farms removed these animals from their herd. One participant that had been heavily impacted by Johne's disease on their farm and had implemented significant management changes to control the disease was encouraged that their test results only yielded one positive result, which supported the management changes they had put in place in order to help control the spread of Johne’s disease on their farm.

Overall this was a successful project, despite not yielding the expected results. While Johne’s disease remains a concern on most dairies, the management strategies and increased knowledge over the past decade have helped reduce the herd prevalence on dairy farms in Vermont. Future research should seek to quantify the economic impact of Johne’s disease on dairy farms to increase farmer adoption of management techniques to reduce the spread of Johne’s disease.