Final report for ONE24-464

Project Information

Shellfish seed availability is limited in New England in the spring when farmers need it most, and this is due to several interrelated factors. The primary reason for this bottleneck is the reality that there is finite available space to produce microalgae for feed, which is the backbone of any shellfish hatchery. The goal of the present work was to evaluate the efficacy of utilizing heterotrophic microalgae within shellfish aquaculture hatcheries for feeding commercially important species at post larval and postset life stages. The heterotrophic microalgae cultures were two strains of Crypthecodinium cohnii (30556 and 30772), which were compared to commonly utilized photoautotrophic microalgae Tetraselmis sp.(MC:2) and Pavlova lutheri, when used as a early life stage for feed for bay scallops (Argopecten irradians) and eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica). C. cohnii, MC:2 and P. lutheri were cultured and scaled from initial starter cultures (500 µl) through high density 4L vessels which could be harvested for shellfish feed and subsequent fatty acid analysis. The highest growth rates were observed in C. cohnii strain 30772(1) with an estimated daily cellular growth rate of 9,492,267 cells per day, followed by P. lutheri (3,092,907 cells per day), and C. cohnii strain 30772 (2) (1,052,700 cells per day). C. cohnii contained higher concentrations of many fatty acids, though significantly higher amounts of myristic acid (C14:0), palmitic acid (C16:0), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA C22:6n3), than either Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) or P. lutheri. Day 12 dph bay scallop and eastern oyster larvae were then fed the microalgae species of interest at clearance rates of the species of interest at 15,000 cells/ml. Across the experimental period of 24 hrs, the species of microalgae did not significantly influence the observed removal rate by A. irradians larvae but did significantly impact removal rates observed by C. virginica larvae. Bay scallop and eastern oyster post-set (600 µm shell height) clearance rates of the species of interest were evaluated by feeding each species at 30,000 cells/ml. Within the A. irradians trial, there was a significant increase in total cells observed in one of each of the C. cohnii strains with CR30556 (2) increasing to 658,167 ± 85,642.9 cells per ml and 233,292 ± 13,593.1 per ml in CR30772 (2). In the C. virginica trial, a significant increase in cell density was only observed in C. cohnii CR30556 (2) with 111,833 ± 5,988.1 cells per ml at the end of the 24 hr period. Microalgal cells of all species were filtered by both shellfish species at both early life stages, and survival was 100% for oysters, and high for all strains (except for CR30556) with bay scallops. This indicates that the fatty acid profile is better than current photoautotrophic strains utilized in hatcheries, and the cells can be and actively are, filtered by both larval and post-set shellfish, and survival is high in both shellfish species, with all species of microalgae tested. Therefore, while additional work is required, integrating heterotrophic microalgal species which are far more nutritious and more efficient to produce is possible and has the potential to provide significant benefit to industry.

This project was designed to culture three different species of dinoflagellate microalgae through either heterotrophic or standard photoautotrophic methods, utilize the microalgae as early life stage feed for both larvae and post-set shellfish, and to investigate clearance rates and subsequent survival. The three species which were grown were Crypthecodinium cohnii, Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and Pavlova lutheri. The larvae and post-set shellfish that were fed the microalgae were eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) and bay scallops (Argopecten irradians).

Objective 1. Culture C. cohnii, Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri in 15 ml starter cultures through 4 L carboys.

Objective 2. Evaluate shellfish larvae clearance rates of the species of interest. Feed 12 days post hatch (dph) larvae of eastern oysters (C. virginica) and bay scallops (A. irradians) at 15,000 cells/ml of each microalgae species in additional to control feeding regimen of 15,000 cells/ml of Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri.

Objective 3. Evaluate shellfish post-set clearance rates of the species of interest. Feed post-set shellfish of eastern oysters (C. virginica) and bay scallops (A. irradians) at 30,000 cells/ml of each microalgae in additional to control feeding regimen of 30,000 cells/ml of Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri.

Shellfish seed availability is limited in New England in the spring when farmers need it most, and this is due to several interrelated factors. There are only a handful of hatcheries in New England, and they are hampered by high costs of production, primarily due to the need to produce all of the microalgae feed for the broodstock, larvae and post-set shellfish on site. This requirement in turn leads to a cap on shellfish seed produced per unit area, which subsequently leads to lower availability of shellfish seed, and higher seed costs for aquaculture producers in the NE SARE region. Paramount to this issue is the lack of viable space to produce microalgae for feed, which is the backbone of any shellfish hatchery.

The limiting factor in growing enough microalgae is the square footage inside the hatchery needed to grow the algae, with the primary issue being the ratio of low density microalgal cells to media volume within each culture unit. As an example, one of the most common species of algae grown in shellfish hatcheries is Tetraselmis suecica, which is a high lipid dinoflagellete, and is a great species to utilize when conditioning adults prior to spawn, and for feeding shellfish set after metamorphosis. In commercial conditions, at the highest density, this organism can reach up to 3 million cells per milliliter, which only results in 0.06 g of biomass per liter, or over 99.9% water in culture (Helm et al., 2004). This low density is a function of the physiological requirements of photoautotrophic microalgae. Typically, shellfish hatcheries grow a suite of microalgae species to feed their broodstock, larvae and post-set seed such as, Tisochrysis lutea, Isochrysis galbana, Tetraselmis suecica, Chaetoceros calcitrans, Thalassiosira weissflogii, and Pavlova lutheri (Mizuta and Wikfors, 2019; da Costa et al., 2020; Le et al., 2020). All of these species are photoautotrophs, meaning that they utilize carbon, as well as inorganic nutrient sources such as nitrogen and phosphorus, vitamins and minerals, in conjunction with light energy to produce organic materials to grow, divide and maintain metabolic function (Richmond, 2013). In any microalgae system where the species being cultured is a photoautotroph, assuming all other beneficial culture conditions are maintained, the limiting factor is photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), or light energy available to the cells (Richmond, 2013; Fernandes et al., 2015; Borowitzka and Vonshak, 2017). This is due to the fact that as cell density within the culture increases, shading from cells within the light path increases, and therefore, as the cells are further from the light source, less light energy reaches each cell within the culture. This upper limit of photosynthetic productivity becomes the limiting factor in shellfish hatchery production, as the entire output of seed is dependent on the quantity of microalgae grown, and the quantity of photoautotrophic microalgae production is dependent on availability of PAR to each cell.

However, certain species, such as Crypthecodinium cohnii, can take in nutrients and organic carbon sources for energy to grow and divide through a completely different method, known as heterotrophy. Heterotrophic algae species are grown in the complete absence of light, and use an organic source of carbon (often glucose or another sugar) and other nutrients (such as peptone or urea) as their energy source, utilizing procedures similar to those used when culturing bacteria or yeast. Due to the fact that light is no longer a factor, the cultures can reach far higher densities, and C. cohnii can reach cell densities as high as 50 grams per liter as opposed to 0.6 grams per liter for the photoautotrophs currently cultured in commercial shellfish hatcheries (Wen and Chen, 2003; Bumbak et al., 2011; Jareonsin and Pumas, 2021). Producing microalgae that can grow in methods that are not limited by light availability would subsequently allow for greater efficiency and lower cost per unit to produce shellfish seed, which would allow for lower prices for farmers to purchase shellfish seed. C. cohnii is a nonphotosynthetic heterotrophic marine dinoflagellate in which nearly 30–50% of its constituent fatty acids is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), while other polyunsaturated fatty acids are present in trace amounts (Jiang and Chen, 2000). This species is ideal for shellfish hatchery work in that it is high in DHA, which is a critical component of egg production and larval development. This species has been studied extensively and is currently represents the major commercially grown source for DHA (Sijtsma et al., 2010). This species has been studied as an enrichment feed to rotifers, as a feed for copepods and as a substitute for fish-derived oils for fish feeds (Ganuza et al., 2008; Eryalçın et al., 2015).

As a comparison to typical commercial shellfish production methods, Tetraselmis sp. MC:2 and Pavlova lutheri were grown alongside using photoautotrophic methods. Both of these species are standard microalgae species as part of most commercial shellfish hatcheries suite of feed components to broodstock and post-set animals (Helm, 2004; Robert et al., 2001). These species are commonly grown photosynthetically, and they produce both EPA and DHA, though in lower overall amounts than C. cohnii. The methods that were developed and evaluated throughout this project have the potential to have a significant impact on several distinct user groups. Hatchery managers and other aquaculturists can use the knowledge gained in order to take action to incorporate the methods into their production systems to improve the sustainability and profitability of their businesses. Academic researchers can use the information gained regarding heterotrophic microalgae within the context of shellfish farming, to develop new knowledge and innovate novel opportunities to improve and expand domestic aquaculture. The public, seafood industry members, extension and outreach personnel and all consumers of seafood products will benefit, as the condition change from low production and expensive products to greater production and cheaper inputs into the supply chain will benefit numerous stakeholder groups. Growing greater biomass of microalgae per unit volume will allow for greater quantities of larvae to be grown at a lower cost, and will also allow for shellfish to be grown to a larger size prior to being shipped to growers. This would also allow for greater efficiency and lower cost per unit to produce shellfish seed, which would allow for lower prices for farmers to purchase shellfish seed.

Cooperators

Research

Objective 1. Culture C. cohnii, Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri in 15 ml starter cultures through 4 L carboys.

In order to determine the volume of required cell culture to introduce across all experiments, cell counts were performed on the inoculation flasks at the start of each day throughout experiments. Initially, starter cultures of C. cohnii (2 cultivars 30556 and 30772) were received from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) as 500 µl cryopreserved stains, and MC:2 (Tetraselmis sp.) and P. lutheri were received from NOAA (Milford, CT) as 15 ml starter stains. The starter cultures were inoculated into 15 mls of either sterilized L1 media (photoautotrophic media, F/2 microalgae media supplemented with additional trace metals; Guillard & Ryther 1962, Guillard 1975) (MC:2 and P. lutheri) or L1+ media (heterotrophic media, L1 enhanced with glucose (9 g/L) and yeast extract (2 g/L)) (C. cohnii) for 72 hrs at 20°C. All species were grown with constant agitation on shaker tables with heterotrophic cultures maintained at 120 RPM and MC:2 and P. lutheri at 110 RPM. The photoautotrophs were under kept under constant illumination, while the heterotrophs were kept in constant dark. After the initial 72 hr period, the 15 ml cultures were used to inoculate triplicate 125 ml flasks with fresh sterilized media; after 5 days, cultures were used to inoculate triplicate 250 ml flasks with fresh sterilized media; after 5 days cultures were used to inoculate triplicate 1 L flasks with fresh sterilized media; and after 5 days, cultures were used to inoculate triplicate 4 L carboys with fresh sterilized media. Growth within all flasks and carboys was monitored continuously throughout experimentation. Every 24 hrs for 120 hrs a 1 ml subsample of culture was removed from each flask or carboy with a sterilized pipette and immobilized with the introduction of 100 mL 2% Lugol’s solution. Cell counts then manually determined with a hemocytometer. At the conclusion of a 5 day growth period of all four strains, all of the microalgae was batch centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 x g. The supernatant was decanted and the microalgal pellet lyophilized, stored at -80°C, and shipped to Creative Proteomics (Shirley, NY) for FAME analysis.

Objective 2. Evaluate shellfish larvae clearance rates of the species of interest. Feed 12 dph larvae of eastern oysters (C. virginica) and bay scallops (A. irradians) at 15,000 cells/ml of each microalgae species in additional to control feeding regimen of 15,000 cells/ml of Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri.

A series of experiments were performed to evaluate how bay scallop and eastern oyster larvae filtration rates differed at 12 dph between heterotrophic and photoautotrophic microalgae species. Each experiment included triplicates of each treatment as well as controls with no added microalgae; both C. cohnii strains (30556 and 30772), Tetraselmis sp. and P. lutheri, in 2 L aerated aquaria, maintained at 20°C. Prior to experimentation, vessels (2 L) were cleaned with 1% Alcoxonä solution, air dried, and then filled 1.5 L of high-purity filter seawater (0.05 mm filtration). Larvae were introduced to each aquaria at a stocking density of 1 larvae per ml and microalgal cells were introduced to each aquaria at an initial density of 15,000 cells ml. Following introduction of the treatment microalgae, the aquaria were left to acclimate for approximately 1 min before a 1 ml subsample was drawn from each aquaria for initial cell count (t = 0). To compare filtration rates across feeding rate treatments, samples for cell counts were taken at 4, 12 and 24 hrs, the microalgae were immobilized with the introduction of 100 mL 2% Lugol’s solution and cell counts were then manually determined with a hemocytometer.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.2.3). The results of all statistical tests were considered significant at an alpha of 0.05. Following data collection, in order to compare treatments a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with microalgae treatment (n = 4) as a fixed effect. To compare removal rates across dietary treatments a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with diet treatment (n = 4) as a fixed effect. Model assumptions were verified using residual diagnostics and the assumptions of normality were met and verified by the Shapiro–Wilks test. To compare larval removal rates between day 12 bivalve larvae (A. irradians and C. virginica) within a diet treatment, two-sample t-tests were used. Analyses were conducted separately for each treatment to evaluate species-level effects under different experimental conditions.

Objective 3. Evaluate shellfish post-set clearance rates of the species of interest. Feed post-set shellfish of eastern oysters (C. virginica) and bay scallops (A. irradians) at 30,000 cells/ml of each microalgae species in additional to control feeding regimen of 30,000 cells/ml of Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) and P. lutheri.

A series of experiments was performed to address how differences in post-settled (600 µm shell height) bay scallop and eastern oyster filtration rates are influenced by heterotrophic or photoautotrophic microalgae species. Prior to experimentation, 2 L aquaria were cleaned with 1% Alcoxon solution, air dried, and then filled 1.5 L of high-purity filtered seawater (0.05 mm). Each aquaria then received 15 post-set shellfish per tank (600 µm shell height) followed by the introduction of one of the four microalgae strains to achieve an initial density of 30,000 cells/ml. The volume of microalgae to be added was determined by cell counts from the 1 L flasks grown in Obj. 1, performed immediately before initiation of the experiment. Following introduction of each microalgae, the aquaria were left to acclimate for approximately 1 min before a 1 ml subsample was drawn from each vessel for initial experimental culture density count (t = 0). The microalgae were immobilized with 100 ml of 2% Lugol’s solution, and cell densities were determined with manual cell counts utilizing a hemocytometer. Similar to Obj. 2, cells observed within suspension were then recorded at 4, 12 and 24 hrs, and the change in cell density observed across treatment was calculated.

After 24 hrs of culture with one of the four different microalgae species, survival was quantified for the post-set bay scallops and eastern oysters utilized in the experiment. Bay scallop survival was determined by either a) attachment to the aquaria via byssal threads, or lacking attachment, b) response to stimulus (i.e., valves closing following physical agitation). Survival with the eastern oysters was determined with observation under 40X magnification and if valves remained tightly closed following stimulus. Percent survival across all experimental replicates presented as the mean ± standard error.

To compare microalgae removal rates across dietary treatments within post settled bivalves a nonparametric approach was used as the data did not meet the assumptions of normality required for a parametric statistical approach, even with data transformations. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare if median removal rate across the diet treatments were significantly different. If the Kruskal–Wallis test suggested significant differences in median removal, a Dunn’s test with a Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment was used for pairwise comparisons between dietary treatments to identify statistically significant groups. To compare for difference in the removal rate within a dietary treatment, between bivalve species, Mann–Whitney U tests was used (Wilcoxon rank-sum tests).

Farmer collaboration:

The objectives in this project were designed to evaluate the biological feasibility of utilizing novel microalgae in a shellfish hatchery to improve efficiency, reduce costs and increase seed supply throughout the NE SARE region. Given the novel nature of the project goals, all of the farmers provided expertise, experience and recommendations on research goals, future directions, and helped to ground truth outputs and outcomes in terms of commercial realities. Mary Murphy was very helpful in this role, as her years of expertise as a shellfish farmer on Cape Cod was invaluable to help guide the project while it was ongoing, as well as following the conclusion when determining next steps to take, given the success of the NE SARE project.

The 6 farmers in total participated in the research. The extension agent was Joshua Reitsma. The first five farmers actively participated in the project, and were all directly involved in achieving the project objectives. Mary Murphy and Joshua Reitsma were both involved in advisory roles, both during project planning, Mary during the project execution, and both Mary and Josh at the conclusion of the project when planning next steps.

Results

Microalgae cultures

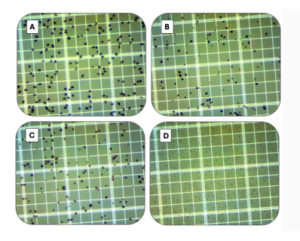

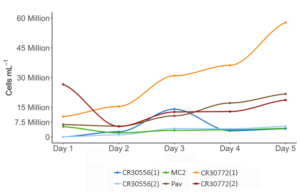

In general, throughout experimentation, larger cell sizes were observed in Tetraselmis sp. MC2 and both C. cohnii strains, while cells were noticeably smaller in P. lutheri (Fig 1). In all production volumes from 15 ml starter flasks through 4 L carboys, all C. cohnii cultures were observed to experience rapid cell growth (Fig 2).The highest growth rates were observed in C. cohnii strain 30772(1) with an estimated daily cellular growth rate of 9,492,267 cells per day, followed by P. lutheri (3,092,907 cells per day), and C. cohnii strain 30772 (2) (1,052,700 cells per day). While C. cohnii strain 30556 (1) (830,500 cells per day), C. cohnii strain 30556 (2) (805,310 cells per day), and MC2 (718,080 cells per day), increased in cell density at a far slower rate (Fig. 2).

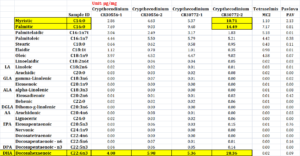

Certain heterotrophic microalgae species, such as C. cohnii, can produce far greater concentrations of beneficial polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acids (AA, DHA, EPA) and higher quality protein amino acid profiles as compared to standard commercial production microalgal species (Wynn et al., 2010; Belanger et al., 2021; Neylan et al., 2024). It has been demonstrated in numerous marine species that PUFAs, especially DHA and EPA are critical for high quality gametogenesis, larval growth and early life stage immune, neurological and cardiac development (Rico-Villa et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2020; da Costa et al., 2023). FAME analysis performed on the four species utilized in this project revealed significant differences in their fatty acid profiles. C. cohnii contained higher concentrations of many fatty acids, though significantly higher amounts of myristic acid (C14:0), palmitic acid (C16:0), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA C22:6n3), than either Tetraselmis sp. (MC:2) or P. lutheri. Specifically, DHA which is a PUFA proven to be critical for gametogenesis and larval health was 0.02 µg/mg in MC:2 and 0.09 µg/mg in P. lutheri, whereas DHA was 4.00 µg/mg and 5.98 µg/mg in the C. cohnii 30556 strains and 5.36 µg/mg and 28.36 µg/mg in the C. cohnii 30772 strains (Table 1).

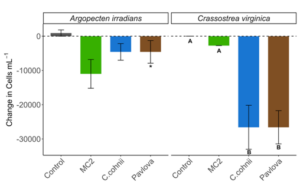

Removal rates by bivalve larvae

Across the experimental period of 24 hrs, the species of microalgae did not significantly influence the observed removal rate by A. irradians larvae, (F(3, 8) = 2.69, p = 0.12) but did significantly impact removal rates observed by C. virginica larvae (F(3, 8) = 13.17, p < 0.01), Fig 3). Within A. irradians larvae, removal rates were not significantly different between the control or the three microalgae diet treatments. In the C. virginica larvae, the lowest removal rate was observed in the Tetraselmi sp. MC:2 treatment which was not significantly different than the control (p = 0.96). Removal rates of both C. cohnii and P. lutheri treatments were significantly different than the Tetraselmi sp. MC:2 treatment (p = 0.01 and p = 0.01 respectively) but were statistically comparable to each other (p = 1). Across species, the removal rates observed in the control, Tetraselmi sp. MC:2, and C. cohnii, were not suggested to be significantly different from one another. However, the removal rates between species in the P. lutheri treatment were significantly different t(3.53) = 3.75, p = 0.025, with a higher removal rate observed by the C. virginica larvae in comparison to the A. irradians larvae with an estimated mean removal of 26,583.33 ± 4,850.54 cells ml compared to 4,583.33 ± 3,305.10 cells ml (Fig. 3).

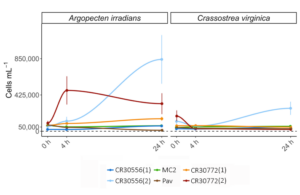

Post Settlement observed changes in cells per ml within suspensions

Over the 24 hrs of the experiment, changes in total cells present in the aquaria differed significantly among microalgae diets in both A. irradians [H (5, n = 18) = 15.69, P < 0.01] and C. virginica [H (5, n = 18) = 16.49, P < 0.01] (Fig. 4). Within the A. irradians trial, there was a significant increase in total cells observed in one of each of the C. cohnii strains with CR30556 (2) increasing to 658,167 ± 85,642.9 cells per ml and 233,292 ± 13,593.1 per ml in CR30772 (2). An increase in total cells over the experimental period was also observed in both of the other C. cohnii strains with an additional 56,833 ± 8,149.0 cells per ml within the cultures of CR30772 (1), and a lesser increase in CR30556 (1) of only 40,792 ± 562.3 cells per ml. The other two diet treatments reported net decreases in overall cells left in suspension with densities of 917 ± 14.9 cells per ml after 24 hours observed in MC2 and 5,500 ± 494.7 cells after feeding P. lutheri. Within the A. irradians trial, changes to overall observed cells left in suspension were only significantly different between the C. cohnii CR30556 (1) strain and P. lutheri (Z = 3.67, padj < 0.01) with all other diet treatments not being significantly different in observed changes to cells left in suspensions (Fig. 4).

In the C. virginica trial, a significant increase in cell density was only observed in C. cohnii CR30556 (2) with a total of 111,833 ± 5,988.1 cells per ml at the end of the 24 hr period. The cell density of C. cohnii CR30556 (1) at the end of the 24 hr period was only slightly higher than the initial stocking density at the beginning of the trial at 55,458 ± 2,467.4 cells per ml, and MC:2 was higher at 61,875 ± 1,986.7 cells per ml. All of the other cultures ended the 24 hr trial period with lower cell densities. This includes CR30772 (1) at 18,333 ± 970.3 cells per ml, CR30771 (2) at 9,875 ± 487.0 cells per ml, and P. lutheri at 9,625 ± 423.8 (Fig. 4). Within the C. virginica trial, changes to overall observed cells left in suspension were only significantly different between the both the C. cohnii CR30556 (2) strain and CR30771 (2) and P. lutheri (Z = 3.19, padj = 0.02 for CR30556 and Z = 3.12, padj = 0.02 for CR30772 for CR30772). Between bivalve species, cell densities were only significantly different for C. cohnii CR30772 (2) and CR30556 (2) (p = 0.01) with lower final cell density in the C. virginica aquaria than A. irradians (Fig. 4).

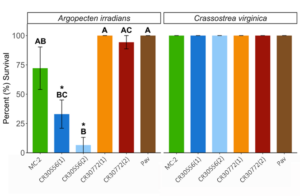

Percent Survival

Percent survival differed within the A. irradians trials among microalgae species [H (5, n = 18) = 18.51, P < 0.01] but were similar among all microalgae species in C. virginica trials which resulted in 100% survival across all microalgae species (Fig. 5). Within the A. irradians trial, exposure to the C. cohnii strain CR30556 reported a significantly lower percent survival when compared to the P. lutheri diet (Z = -3.11, padj = 0.03), and the C. cohnii strain CR30772 (1) (Z = -3.64, padj < 0.01), but was statistically comparable to MC:2 (Z = -1.94, padj = 0.79) and C. cohnii strain CR30772 (2) (Z = -2.72, padj = 0.10) following the 24 hr experimental period. A similar trend was observed when A. irradians was fed C. cohnii CR30556 (2) which also resulted in a significantly lower percent survival post-exposure to P. lutheri (Z = -3.64, padj < 0.01), both C. cohnii CR30772 strains (1) and (2) (Z = -3.11, padj = 0.03 and Z = -3.28, padj = 0.02, CR30772 (1) & CR30772 (2) respectively), but was statistically comparable to MC:2 (Z = -2.53 padj = 0.17). The percent survival observed in A. irradians when fed either C. cohnii CR30556 strains was not significantly different between (1) or (2) (Z = 0.68 padj = 1). Percent survival within a dietary treatment, between A. irradians and C. virginica was statistically similar in the dietary treatments of MC:2 (p = 0.18), both CR30772 strains (1) and (2) (p = 1 and p = 0.40, CR30772 (1) & CR30772 (2), respectively), and P. lutheri (p = 1; Fig. 8). Percent survival in both C. cohnii CR30556 strains was significantly lower in A. irradians when compared to C. virginica (p < 0.01 and p < 0.01, (1) and (2) respectively, Fig. 5). No mortality was observed following exposure to either C. cohnii strains within any C. virginica trials.

Discussion

When cultured at any volume between 15 ml to 4 L across all species and strains, over time cell density increased, which is what would be expected in standard microalgae culture conditions. This finding establishes the validity of the techniques as a comparison between photoautrophic and heterotrophic species; at least when replicating standard hatchery techniques at lower culture volumes. The interesting finding was how much quicker the heterotrophic microalgal cell density increased, and the overall final cell density over a relatively short period of time. There are no species of photoautotrophic microalgae which are currently cultured in commercial shellfish hatcheries which reach 55 million cells per ml, and certainly not in 120 hrs after inoculation. The increase in biomass is several orders of magnitude greater than current methods, and if the techniques to utilize these species in shellfish hatchery production can be optimized, the greater efficiency in early life stage feed production could have a significant impact on the output and economic viability of commercial operations.

The needs of larval and early life stage shellfish in terms of PUFAs such as DHA and EPA are well known for different commercially important shellfish species. While the fatty acid composition of the microalgae species chosen for this project have been previously published, the actual content varies significantly depending on the specific culture conditions. Therefore, it was important to compare these species when grown outside of a lab and under actual commercial shellfish hatchery conditions. It was interesting to note the content of the microalgae species included in this project, as there were vast differences in many of the fatty acids evaluated, especially the biologically important PUFAs. While this work was preliminary and no commercial integration should be justified given the lack of fully developed techniques, the heterotrophic species that were evaluated have far greater nutritional profiles than currently utilized species in shellfish hatcheries.

Every shellfish species filters particles of different sizes at different rates, due to both preferred size and composition, as well as biological limitations relating to anatomical variation between species. This fact was demonstrated in the current work, in that the reduction in cells differed between shellfish species, within shellfish species depending on the microalgae fed, as well as between larval and post-set animals within each species. The various differences were also shown in trials with single microalgae fed, which, while important for preliminary work such as this to demonstrate initial efficacy, is not standard practice in most hatcheries. It was important to show, for example, that bay scallops appear to filter MC:2, C. cohnii, and P. lutheri at similar rates, and universally lower rates than eastern oysters, while larval oysters appear to prefer C. cohnii, and P. lutheri more than MC:2 when fed single species diets. This differs from post-set animals, in that oysters consume all microalgae at similar rates, whereas bay scallops don’t filter C. cohnii CR30556 (2) or CR30772 (2) at the same rates that they filter all of the other tested species. These results simply illustrate that certain species of microalgae are preferred over others for different shellfish, within those species of microalgae certain strains are preferred over others, and that even those findings are not consistent across life stages. This finding is congruous with standard shellfish hatchery methods utilizing photoautotrophic microalgae feeding strategies, in that operators know that certain species (such as MC:2) are too large to be filtered at the larval stage, whereas they are actually preferred at the broodstock or post-set stages. Additionally, it is well known that certain species of microalgae are preferred by some shellfish broodstock, while the same microalgae species are almost universally rejected by others. This indicates further investigation is warranted, as well as the clear need to experiment with mixed diets to move toward actual hatchery diet development and replication of techniques which could be integrated commercially.

This project resulted in numerous interesting findings that indicate, given sufficient experimentation and optimization of methods, heterotrophic microalgae could be integrated into commercial shellfish hatchery production, which would lead to significant output and economic efficiency gains. Perhaps the greatest finding of this work can be found in Figure 5, which is survival over the feeding trial for post-set animals. These results demonstrate that while microalgae cells of all species were being filtered (Fig. 4), survival was 100% for oysters, and high for all strains (except for CR30556) with bay scallops. In conjunction with the finding that the fatty acid profileof the heterotrophic strains are better than current photoautotrophic strains utilized in hatcheries, the cells can be and actively are, filtered by both larval and post-set shellfish, and survival is high in both species and all species of microalgae tested. Therefore, while additional work is required, integrating heterotrophic microalgal species which are far more nutritious and more efficient to produce is possible and has the potential to provide significant benefit to industry.

References

Bélanger, A., Sarker, P. K., Bureau, D. P., Chouinard, Y., & Vandenberg, G. W. (2021). Apparent digestibility of macronutrients and fatty acids from microalgae (Schizochytrium sp.) fed to rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): A potential candidate for fish oil substitution. Animals, 11(2), 456.

Borowitzka, M. A., & Vonshak, A. (2017). Scaling up microalgal cultures to commercial scale. European Journal of Phycology, 52(4), 407-418.

Bumbak, F., Cook, S., Zachleder, V., Hauser, S., & Kovar, K. (2011). Best practices in heterotrophic high-cell-density microalgal processes: achievements, potential and possible limitations. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 91, 31-46.

Cheng, P., Zhou, C., Chu, R., Chang, T., Xu, J., Ruan, R. & Yan, X. (2020). Effect of microalgae diet and culture system on the rearing of bivalve mollusks: Nutritional properties and potential cost improvements. Algal Research, 51, 102076.

da Costa, F., Cerviño-Otero, A., Iglesias, Ó., Cruz, A., & Guévélou, E. (2020). Hatchery culture of European clam species (family Veneridae). Aquaculture International, 28(4), 1675-1708.

da Costa, F., González-Araya, R., & Robert, R. (2023). Using combinations of microalgae to condition European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) broodstock and feed the larvae: effects on reproduction, larval production and development. Aquaculture, 568, 739302.

Eryalçın, K. M., Ganuza, E., Atalah, E., & Hernández Cruz, M. C. (2015). Nannochloropsis gaditana and Crypthecodinium cohnii, two microalgae as alternative sources of essential fatty acids in early weaning for gilthead seabream. Hidrobiológica, 25(2), 193-202.

Fernandes, B. D., Mota, A., Teixeira, J. A., & Vicente, A. A. (2015). Continuous cultivation of photosynthetic microorganisms: approaches, applications and future trends. Biotechnology Advances, 33(6), 1228-1245.

Ganuza, E., Benítez-Santana, T., Atalah, E., Vega-Orellana, O., Ganga, R., & Izquierdo, M. S. (2008). Crypthecodinium cohnii and Schizochytrium sp. as potential substitutes to fisheries-derived oils from seabream (Sparus aurata) microdiets. Aquaculture, 277(1-2), 109-116.

Guillard R, Hargraves P (1993) Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chrysophyte. Phycologia 32:234–236.

Guillard RR (1975) Culture of phytomicroalgae for feeding marine invertebrates. Springer, p 29–60.

Guillard RR, Ryther JH (1962) Studies of marine microalgae diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Canadian journal of microbiology 8:229–239.

Helm, M.M.; Bourne, N.; Lovatelli, A. (comp./ed.). 2004. Hatchery culture of bivalves. A practical manual. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 471. Rome, FAO. 177p.

Jareonsin, S., & Pumas, C. (2021). Advantages of heterotrophic microalgae as a host for phytochemicals production. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 9, 628597.

Le, T. S., Southgate, P. C., O’Connor, W., Abramov, T., Shelley, D., V Vu, S., & Kurtböke, D. İ. (2020). Use of bacteriophages to control Vibrio contamination of microalgae used as a food source for oyster larvae during hatchery culture. Current Microbiology, 77, 1811-1820.

Mizuta, D. D., & Wikfors, G. H. (2019). Seeking the perfect oyster shell: a brief review of current knowledge. Reviews in Aquaculture, 11(3), 586-602.

Neylan, K. A., Johnson, R. B., Barrows, F. T., Marancik, D. P., Hamilton, S. L., & Gardner, L. D. (2024). Evaluating a microalga (Schizochytrium sp.) as an alternative to fish oil in fish-free feeds for sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria). Aquaculture, 578, 740000.

Richmond, A. (2013). Biological principles of mass cultivation of photoautotrophic microalgae. Handbook of microalgal culture: applied phycology and biotechnology, 169-204.

Rico-Villa, B., Le Coz, J. R., Mingant, C., & Robert, R. (2006). Influence of phytoplankton diet mixtures on microalgae consumption, larval development and settlement of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). Aquaculture, 256(1-4), 377-388.

Robert, R. and Trintignac, P. 1997. Microalgues et nutrition larvaire en ecloserie de mollusques. Haliotis. 26:1-13.

Wen, Z. Y., & Chen, F. (2003). Heterotrophic production of eicosapentaenoic acid by microalgae. Biotechnology advances, 21(4), 273-294.

Wynn, J., Behrens, P., Sundaraajan, A., Hansen J., and Apt, K. 2010. Production of single cell oils by dinoflagellates. In: Single cell oils: Microbial and algal oils, 2nd edition. (eds. Z. Cohen and C. Ratledge), pp. 115-129. AOCS Press, Champaign, IL.

This work was proposed as preliminary, in that utilization of the species chosen for these experiments have not been evaluated for potential integration as supplemental or replacement microalgae feed for early life stage shellfish production. None of the methods for microalgal production, or feeding to larvae or post-set were optimized. The project was intentionally designed to be a range finding exercise to determine if there is enough promise to justify further investment of experimental resources. However, given that the work took place within a commercial hatchery, with commercial hatchery staff, the results are applicable and should be evaluated through the lens that the findings were not simply in an academic lab which may or may not transfer to industry. This work took place within the context of a commercial farm, and there is no question as to if the findings would translate to industry, because it was a group within the industry that performed the trials.

If heterotrophic microalgae are incorporated into hatchery commercial production in the future, as the integration scales beyond 4 L volume, the methods will need to be modified. These modifications to optimize the differences in nutritional and logistical requirements of the different types of algae, will result in techniques which are very different than current hatchery microalgal production methods, and more similar to current approaches of large companies producing omega oil for human consumption. While this will require a significant initial investment by the hatchery, and while the approach has been extensively developed within the context of large biotechnology companies, techniques and equipment which would be appropriate for farming and not neutraceutical output would need to be considered.

The project results indicate that the fatty acid profiles of the species tested are better than current photoautotrophic strains utilized in hatcheries, the cells can be and actively are, filtered by both larval and post-set shellfish, and survival is high in both species and all species of microalgae tested. Therefore, while additional work is required, integrating heterotrophic microalgal species which are far more nutritious and more efficient to produce is possible, and has the potential to provide significant benefit to industry.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

All data generated throughout the project (microalgae culture conditions, nutrient composition, larval feeding and survival, post-set feeding and survival) were saved at Ward Aquafarms, LLC and can be provided to stakeholders by request. Results have been communicated to extension personnel, regulators, farmers and persons of the public who are either currently involved in the industry, or interested in shellfish aquaculture and microalgae production optimization. Dissemination of results occurred through both formal discussions as well as informal conversations between growers and extension agents. Dr. Ward and his staff are active members within the regional aquaculture community, and all parties interested in visiting the operation were encouraged to visit the hatchery and evaluate the heterotrophic microalgae experiments.

The major deliverable from this project was a comprehensive evaluation of the ability to culture microalgae through means that are far more efficient than current standard methods, and the ability of shellfish to actively filter and consume these microalgae as food. The method of disseminating this information to stakeholders varied given the audience that was trying to be reached. For other farmers in the region, Dr. Ward also put together the results of the project into a format which has been posted on the Ward Aquafarms, and can be forwarded to farmers by request.

The presentations occured at the Scallop Bay Shellfish Hatchery, when I was able to offer a series of tours and outreach opportunities in the spring of 2025 to commercial farmers, extension agents, municipal natural resources staff, academic researchers, and members of the public to learn more about shellfish aquaculture, our hatchery, our techniques and research goals and outcomes, including the NE SARE project. There were no materials generated to be provided at these outreach events, because the activity was designed to be more hands on and similar to a tour and Q&A session as opposed to a sit down presentation. The active format worked very well and all participants were engaged and interested, and professed a desire to follow up to learn more about shellfish aquaculture and improvements to hatchery techniques.

Learning Outcomes

The target audience for this particular project were the project participants, as well as extension personnel, farmers in the region, and academic partners in associated research, as the intentionally limited scope of the objectives was designed to test the approach at a broad scale, to inform subsequent research refining an approach which could be reported to industry. The goal of continued development would be a change in knowledge within the academic research community, a change in action within the shellfish hatchery community to incorporate the new methods, and a change in condition within hatchery production, from inefficient, costly approaches to techniques which lead to greater efficiency and overall industry resiliency.

This rationale for the current project was to evaluate the potential of heterotrophic algae, and to develop preliminary data, which would serve as the basis for further in depth investigation. The outputs from this work are the methods which were developed to incorporate microalgae grown through hetrotrophic techniques into shellfish aquaculture production. These methods include the media conditions and biomass production with the novel species, as well as algae consumption rates by both larvae and post-set shellfish.

Project Outcomes

The methods that were developed and evaluated have the potential to have a significant impact on several distinct user groups. Hatchery managers and other aquaculturists can use the knowledge gained in order to take action to incorporate the methods into their production systems to improve the sustainability and profitability of their businesses. Academic researchers can use the information gained regarding heterotrophic microalgae within the context of shellfish farming, to develop new knowledge and innovate novel opportunities to improve and expand domestic aquaculture. The public, seafood industry members, extension and outreach personnel and all consumers of seafood products will benefit, as the condition change from low production and expensive products to greater production and cheaper inputs into the supply chain will benefit numerous stakeholder groups.

The issue is a chronic problem of high costs and low production of shellfish seed, which is preventing industry expansion and long term resiliency. This problem stems from a bottleneck in early life stage food sources, which hinges on photoautotrophic microalgae, and the inherent limitations of current culturing techniques. C. cohnii is a species of microalgae than can be grown through heterotrophic means, with different carbon sources and no light requirement, which leads to far greater biomass production per unit volume. These strains were cultured adjacent to photoautotrophic microalgae utilized in standard shellfish hatchery production. All of the algae species were then fed to shellfish larvae and post-set to evaluate the value of incorporating heterotrophic feed sources into commercial shellfish methods.

The research objectives were designed to collect preliminary data on the novel approach, with the intent of evaluating the utilization of heterotrophic microalgae for use in shellfish aquaculture, as the technique has not been attempted elsewhere. Informal discussions with farmers, extension professionals, and the public at large, had generated interest in the concept, and therefore the project was proposed to significantly improve the output and efficiency of shellfish hatcheries throughout the US and specifically the NE SARE region. The microalgae species currently utilized in shellfish hatcheries across the US were chosen and evaluated for their utilization decades ago, in some cases over 70 years ago, which is a long time with little progression. These species were chosen based on rudimentary knowledge of shellfish physiological needs at the time, and it is inconceivable that with all of the research into shellfish nutritional needs based on immune function, growth and survival and gametogenesis, that these same species are ideal and cannot be improved upon. This work was undertaken with the belief that there are improvements to be made to current early life stage feed protocols, and the results of the current project justify further investigation.

This project was proposed as a first pass at evaluating feeding motile heterotrophic microalgal cells to shellfish at larval and post-set stages. It was unknown if these microalgae species could be cultured using the same techniques as photoautotrophic algae in a hatchery setting, and it was determined that the same methods are viable, which means that the approach could be successfully integrated into commercial production. Additionally, it was unknown if the shellfish could feed on these species of microalgae at these two early life stages, and if they could, if they would survive. It was shown through this work that bay scallops and eastern oysters can both feed on these species with low to no mortality. It was also shown that the microalgae species produced have far better fatty acid profiles than the photoautotrophic species currently cultured in commercial hatcheries. If the project was to be initiated today with the knowledge that was gained throughout the experiments, the methods would be largely the same. The objectives were designed in such a way to evaluate the exact concepts outlined above, and the results successfully led to the conclusions that the experiments were designed to investigate. Now that these results have been determined, as with any well performed research project, there are typically more avenues of future investigation than there are definitive questions answered, and that is no different in this instance. However, the result of this work, is the determination that there is reason to continue this line of investigation, for the long term benefit of shellfish aquaculture in term of biological and economic efficiency and overall industry progress and sustainable expansion to the benefit of all agricultural stakeholders.