Progress report for ONE24-466

Project Information

The objectives of the two phases of this proposal are the following:

Phase I:

Design, prototype, test, and document the following products with the participating farms:

- Automatic differential humidistat for grain drying Automatic small scale blueberry sorter

- Automatic greenhouse reemay mover

Phase II:

Advertise, prepare, and conduct 3 workshops for farmers in which attendees learn the skills and acquire the tools to build microcontroller projects for working farms. Participating farmers can use the workshop to build themselves a specific device of their choosing or use the workshop to build a sample device.

All Farms have problems that are bespoke; each farm has different crops, soil, weather, markets, size, labor conditions, and financial situations. Small farms have the added problem that custom solutions take longer to be profitable. Arduino (and its variations) is a problem solving system designed specifically for prototyping and solving unique problems for use by amateur designers and developers. Arduino’s educational spirit (open source everything) and modular, mass produced parts make it easy and affordable to use.

Farms already use arduino for many applications in control (irrigation, heating, cooling, ventilation), automation (motors, processing crops, cleaning/washing), monitoring/communication (data collection, marketing, sales).

Phase I of this grant proposes completing 3 microcontroller projects. The three projects are all projects for which no solution currently exists on line or as a product. More importantly, they are projects which farms have requested and for which there are applications on more New England farms. And finally, they are projects which are more complex and larger than a simple sensor or smart switch and therefore require research and iteration.

Project 1: Differential humidistat for drying grain in plenum bin. Uses logic and automation to control electricity to a blower for maximizing grain drying rate and minimizing energy use. Uses inlet and outlet airstream humidity and temperature as inputs , and a relay to the blower(s) as output. Anni Schmidt and I prototyped and installed this device in 2023 (with help from intern Meagan Rittmanic, Olin College). The remaining work is to test the prototype in the lab, collect data, and validate the results.

Project 2: Blueberry sorting. Sorts blueberries into marketable, over ripe, and under ripe. Uses color and shape recognition sensors as input, and a servo gate as output. We will attempt to integrate open source machine learning code with a microcontroller and a servo gate and use sorted blueberries as a training data set.

Project 3: Reemay moving. Automatically covers greenhouse crops with reemay on cold nights, and uncovers them on warm mornings. Uses temperature and light as input, and a motor control as output. The computer code for this project is simple, while the mechanism and construction will be extensive.

Phase II of the project (arduino workshops for farmers) seeks to provide a service for farmers which they have requested; hands-on workshops where farmers can familiarize themselves with microcontrollers and acquire the tools and skills to do their own projects.

Teaching microcontroller use to farmers has three benefits:

- Allows farmers to complete their own projects

- Allows farmers to understand and use microcontroller recipes from the internet

- Allows farmers to grasp and communicate the possibilities and limitations of microcontrollers when seeking help or products from other people.

In the world of microcontrollers there is a basic level of knowledge, vocabulary, and tools that allow a designer to use the open source online resources to accomplish a lot without ever needing expertise in either electronics or programming. This is because the difficult circuits and code are already available and can be either purchased inexpensively or downloaded for free. Best of all, there is a “modular” aspect to both the sensors, the circuits, and the code that allows building blocks (think of legos) to be assembled in a variety of ways to accomplish different tasks. This modularity on three levels (hardware, or "atoms"; electrical wiring, or "wires"; and computer code, or "bits"), allows different projects to be similes of each other.

Cooperators

Research

1/7/25 Research/Construction Update:

To date I have conducted research and construction in the Phase 1 areas of this grant: 1. automatic dehumidistat, 2. blueberry sorter, and 3. greenhouse reemay mover. Below I summarize this progress:

- Automatic dehumidistat. In August I met with the participating farmer, Chuck Currie, Freedom Food Farm, and collected information on his current grain drying system and what improvements he proposes. In September and October I built a test system to compare humidity sensors and collected data on temperature/humidity sensors that will be useful in March when I start construction of the bench-scale prototype. I was able to use my clothes dryer as a proxy source of a humid airstream and this worked well, allowing me to passively collect data while doing the chores. I am focusing on using the DHT-22 temperature/humidity sensor, as it is inexpensive and accurate enough. Through analyzing the data from my clothes dryer, I think I now understand a technical property of the DHT-22 that was confounding my previous attempts to code the control logic on the differential humidistat; namely, that the temperature and relative humidity readings are out of phase by a matter of seconds, which makes using the data for determining absolute humidity a difficulty. If true, this hypothesis would explain problems Anni Schmidt (who wrote the original code) described in our previous attempts at using these sensors on a grain dryer. One remaining strategic question is whether or not it is possible to monitor the grain dryness directly, or whether, as I have assumed in the past, it is necessary to use moisture in the airstream as an indicator of drying activity. This will be the first question I address in the Spring.

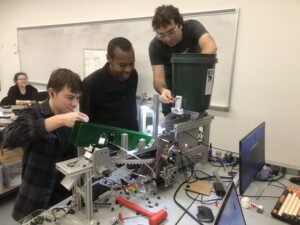

- Blueberry sorter. In August I met with Dr. Mbanisi of Olin College of Engineering. We agreed to prototype the blueberry sorter with a team of students from his Robotics and Mechatronics class at Olin. In August we collected data on sorted blueberries (blueberries sorted by the farmer by hand) by taking digital photos of blueberries with a special shape and color recognition camera. This data became the basis for training a computer to discern between the 3 proposed categories of blueberry: Ripe, underripe, and overripe. The student team convened in September: Jacob, mechanical/electrical, Alana, electrical, and Luke and AJ, code. Through the Fall I worked closely with Dr. Mbanisi and the team to develop a working prototype which will be used in field trials July 2025. The blueberry sorter mechanically processes blueberries from a hopper to a single file of blueberries on a conveyor belt. The blueberries pass under a camera that sends images to a microcomputer. The microcomputer classifies the individual blueberries and then activates pneumatic valves that use bursts of air to separate the blueberries into 3 bins. By the end of their semester, AJ, Alana, Jacob, and Luke had a benchtop prototype that worked in the lab (though in December it's difficult to obtain unsorted local blueberries to test the device). The prototype sorts about a blueberry per second, has a materials cost of about $500, and an accuracy rate between 85-93% . One other interesting feature is that it is really a "delicate object sorter", quickly adaptable to sorting any berry or seed. There are still, however, mechanical and code issues that the students wish to address in the coming semester. Field trials for the Sorter will begin in July 2025, and by then I hope to have two working prototypes so we can get the most data possible from the limited time during which we'll have fresh blueberries. Adam and Carissa (the participating farmers) are ideal collaborators; they are available and supportive when consulted, and go out of their way to make the farm and blueberry sorting shack available to the engineers on the project. I am cautiously optimistic that within the $500 for parts budget, a small-scale blueberry sorter can be made.IMG_6904 2.

Blueberry Sorter under development

Jacob and AJ working on the Blueberry Sorter

Close-up of Blueberry Sorter electronics at Olin College of Engineering - Reemay Mover. In August and September I prototyped a bench scale model of the Reemay Mover and wrote the software sketch and tested it. By October I had a 1/4 scale model working in my front yard. The design is based on a motorized roller for greenhouse side flap ventilation, a proven product already familiar to many winter production greenhouse farmers. To date I've made three attempts to construct the Reemay Mover at full scale (50' x 30') in one of Roots Farm's winter production greenhouses. The control, logic, and electrical (bits and wires) part of the machine works well. The design principle of "fail-to-manual" works well in this machine; a farmer can quickly disconnect the motor and roll the reemay by hand. So even without the "robotic" part of the device, it is still saving labor. The mechanical part (the atoms) is proving difficult. Problems of steering error correction, proper tensioning of the reemay, and tucking in the sides of the reemay have all been tricky. I have poured work in to this part of the project and made some progress without drastically changing the design path or increasing the cost of materials in the machine. However, it is also prudent to consider other design paths that use the same logic and controls but a different mechanical scheme. The unforeseen mechanical problems with this project have quickly eaten up the planned labor budget. However, because I feel like the problems can be solved, and I feel this design could have a large positive impact in New England, I'm committed to making it work. I believe I can borrow labor hours from the other phase 1 projects and stay within the overall phase 1 budget. Kelli and Mike (Roots Farm) are enthusiastic collaborators; their farm is already compact, carefully planned, and technologically advanced, making it a good fit for testing a technology like the Reemay Mover.

Full-scale Reemay Mover

Photography by James Davis

UPDATES AS OF JANUARY 2026:

SARE annual report 2 OVERVIEW:

Between January of 2025 and January 0f 2026 I was able to complete work on the following prototypes: The Grainbrain, Blueberry Sorter, and Reemay Robot. Also, in November of 2025, I held the first of 3 Workshops to introduce microcontrollers to farmers. Of the three prototypes, The Grainbrain was a total success– there are now 3 working prototypes in the field and the electronics, code, and mechanical parts of the design are working. The Blueberry Sorter was a partial success; with a lot of work we were able to get the blueberry sorter working at the farm during the harvest, but only as a lab experiment, never as an integrated part of the farm’s harvesting process. And the Reemay Robot was a partial failure; the code and electronic parts worked well while the mechanical set-up in the actual greenhouse failed to work and was rejected by the farmers and the workers.

The first workshop, held at the Firehouse on Novemember 22 and attended by 17 people (6 farmers(representing 4 farm projects), 2 instructors, 4 volunteer-students, 3 cooks, 1 professor of engineering and her child). It was a success in the sense that in one day we managed to complete 4 micro-controller projects. It made us nervous, however, about holding the next 2 workshops anywhere other than the Firehouse, where the large space, shop full of tools, hardware, and spare parts, and adequate industrial kitchen made the whole day possible.

Below is more information about each prototype and the workshop.

Blueberry Sorter:

On April 5, 2025, the students from Olin College’s Mechatronix class (Alana, Luke, Jacob, and AJ) “handed off” the Blueberry Sorter project to James Davis and me. James and I began building a second prototype of both the mechanical and computer parts of the device.

The Blueberry Sorter is a challenge: Can the “new wave” of inexpensive electronic parts and the sudden availability of free Machine Learning software enable a small blueberry farm to own and use a miniature sorter that automatically sorts picked blueberries into three categories; ripe, underripe, and overripe? We are inspired by the history of the “garagiste” farmers of France, who, after WWII, made their own wine-making equipment and started a revolution in farm-produced wines that increased the prosperity and social status of grape farmers.

The challenge of the blueberry sorter can be divided into a mechanical problem and a computer problem, which are related. The mechanical problem is called “singularization”; the creation of a stream of single blueberries from a hopper or pile of blueberries. Singularization is made more difficult when the blueberries are soft, easily bruised, and varying in size. The computer problem is how to position a camera so that the most efficient use is made of computer processing power and time when viewing and classifying the “singularized” stream of berries. The relationship between singularization and processing is a give-and take between them: A camera positioned farther away can make several images of a “sloppy” stream of several blueberries, or a camera positioned closer can make a single image of a well-singularized blueberry. James and I, building on the work of the Olin students, chose to pursue a well-singularized blueberry stream along with a close-up image approach. To improve the mechanical singularizer we built a “roulette wheel” that accepted one blueberry per cup. To improve the conveyor belt we built a conveyor belt in the form of a “V” instead of a flat conveyor belt. The “V” shaped belt, driven with a stepper motor instead of a regular motor, worked very well. The V shape helped to get the blueberries gently from a hopper into a row. The stepper motor allowed the possibility of moving the belt back and forth in a shaking motion, mimicking the motion a hand might use when distributing soft objects from a cup or bowl into a row. To solve the computer processing problem James and I used a bigger microcontroller (Intel NUC instead of a Raspberry Pi– $100 instead of $30). We think the larger microcontroller could work but software compatibility issues caused us to use a recycled PC instead, which solved the software problems and allowed us to run real time video of the camera images and classification results.

The purpose of the more powerful processor was to allow us to use an open source visual machine learning software (YOLO), which worked well, and proved that it is possible to use the “revolution” in machine learning software to solve problems for small farms, although we may still be a few years away from that brave new world…

Both the construction of the soft-berry singularizer, and the integration of the software, presented more challenges and difficulties than we anticipated, but by the start of the blueberry harvest in July 2025 we had a prototype sorting blueberries at a rate of ~1/second and with an overall accuracy of 80%-90%. We did not, however, succeed in getting the blueberry sorter to the level of reliability and simplicity of operation that would allow the farm to use it as a primary sorter without constant engineering-babysitting.

We worked at the farm in parallel with the human-powered sorter. One interesting feature of this process: Most machine learning programs are trained on data scavenged from the internet. In our case we trained the software on photographs of human-sorted blueberries– the blueberries themselves. After the prototype sorted the blueberries, we passed them back to the human sorter for re-sorting. The “mistakes” the computer made could then be re-submitted to the computer as training data, thereby improving the program’s accuracy. We found that we could also improve the program by re-submitting different photos of the same blueberries already classified by the human sorter. In this “leap-frog” learning method, we urged the computer to improve.

Another important detail: Assuming that a human sorter relied on their eyes to sort blueberries, we only used images as input data. In fact, the software we used is designed for images. It is likely that human sorters also rely on touch (ie, how soft a berry is). It is also possible that a second or third data stream (ultrasound for example) humans don’t even have but could be cheaply implemented by a computer might work well. Ultrasound is very inexpensive and could “bear fruit” when classifying berry ripeness.

By the end of the berry harvest in August, two things were clear: First, we felt confident that with more effort the goals of the project could be achieved; a mini-sorter using ~$500 in parts could be used by a small farm to sort blueberries automatically. Second, we are still one or two prototypes away from reaching this goal. James and I agree on the direction we think the design should go in.

What remains to be done for this prototype is to document the design and critique the design so that improvements can be made when there is an opportunity to do so.

James and I both feel that the "roulette wheel" could actually be removed from the machine if the hopper/belt assembly was improved. James imagines a set of tubular (or circular in cross-section) belts singularizing more than one file of blueberries at the same time, with the camera positioned above the end of the belts and classifying the berries as they approach the end of the belts. The sorting could be done with compressed air or servos. We also think it might be useful to include a "trampoline" or pressure sensor which adds another means of removing soft or rotten blueberries. This is because soft blueberries are the most important to remove from the packaging stream, as they tend to rot the other berries and reduce the overall shelf-life of the packaged pint.

Grainbrain:

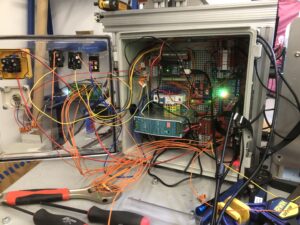

In March 2025 I built a “test tower”, essentially a miniature plenum drier for grain. The test tower was designed to dry a few pounds of grain but mimic the static pressure and airflow rates per pound of a standard plenum dryer. The test tower allowed me to moisten and dry the same few pounds of grain (in this case Wharthog Wheat grown in Essex MA) again and again while testing different Grainbrain electronics and code. The test tower worked well, and it allowed me to quickly test, calibrate, and modify Grainbrain electronics and code. I also had valuable input and suggestions from 3 farmers: Chuck Currie of Freedom Foods Farm (the participating farmer for this project), Noah Kellerman of Aprilla Farm (whose complaints about plenum drying led to the original prototypes), and Rob Eckman of Crabapple Farm. I wrote new code for these prototypes, using the blueprint created by Anni Schmidt, but using an architecture of functions that many people think is easier to follow and understand for non-computer scientists. I also added several features to the overall design, with help from James Davis: 1. A clock and datalogger so the farmer has a log of the “dry” and can analyze how long the grain spent at various moisture contents (MCs), how long the blower was running, and what the various weather conditions were. 2. A set of equations that calculate the Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC) for various grains, temperatures, and relative humidities. 3. A LCD that displays real-time data. And, 4. A method for the farmer to periodically enter the actual grain MC as tested by the farmer with a grain moisture tester.

The Grainbrain works by comparing the absolute humidity of the air leaving the grain to the absolute humidity of the air entering the grain. If the airstream is gaining moisture, then the grain is drying. The Grainbrain turns off the blower when the airstream is not gaining moisture. It re-starts the blower either after a pre-set time elapses, or when the the inlet conditions (of temperature and rH) indicate potential for drying. As a result of conversations with farmers, the logic of the code divides the drying process into two epochs; a first epoch when the grain is moist (>20%MC) and needs more ventilation regardless of whether drying is occurring, and a second epoch (<20%MC) when the grain is mostly dry and needs less ventilation but requires more favorable drying conditions.

The various set-points of temperature, humidity, time, and the calculated EMC equations can all be modified in the code so a farmer can (in theory by themselves or with a little email support from a coder) tweak the Grainbrain to suit their particular needs. In addition, a single Grainbrain could control the blowers on several plenum bins. And, a single Grainbrain could be used for any size bin, so the Grainbrain is agnostic to scale. The purpose of the Workshops in this grant is to enable farmers to make these tweaks for themselves and/or understand enough to effectively seek help with the adaptations needed for their farm.

By May of 2025 I was satisfied that the prototype works well on the test tower, and completed three Grainbrains. One I installed at Freedom Food Farms where Chuck was drying wheat and Emmer. The other I sent to Noah Kellerman who was drying wheat, rye, and black beans. Noah discovered a couple problems with the prototype which I fixed on the remaining unit and sent to him so that he could quickly integrate it into his black beans, which was the last crop he dried this season. The hardware for each Grainbrain costs under $90, which is a beautiful thing. A farmer can spend a day or two building a Grainbrain which will pay for itself in saved labor and electricity on the first crop it dries.

One interesting detail I encountered which is a common issue in electronics is that the mass-produced electronic parts vary in quality and dependability. So while the purpose of this project is to see if the “new wave” of low-cost electronic parts can be of service to small farms, it is occasionally of value to “pay up” for a part of slightly higher quality in order to increase dependability. Our efforts to parse this fine line are complicated by the fact that in today's supply chain the brands, quality, construction, and features of the same parts can vary from month to month. In the case of the Grainbrain, we opted for an incredibly cheap ($3) but not dependable sensor (the DHT-22) and then increased its dependability with a software patch and shielded sensor cables. And, we paid up for a better relay ($5 instead of $1.37). In the future new parts will become available and farmers that build Grainbrains will have to choose which parts to use and how to integrate them. Integrating different parts is where the Workshops can help. The purpose of the workshops in this grant is to familiarize farmers with enough of the technology so that they can either do this changing of parts themselves, or “speak the language” with someone who can help them. What is really cool about microcontrollers is that whatever software changes are needed can be done over email by many people who are eager to help online around the world and at all hours! There are now many more people who know how to fix computer code than people who know how to put a disc harrow on a three point hitch!

The final step for the Grainbrain is to document the prototype which includes a written account of the prototype, the Bill Of Materials with links to buy the parts, and the computer code (Arduino IDE code). This documentation is complete save some editing, but I am having problems uploading it to Farmhack.org, which we are currently trying to resolve.

Reemay Robot:

We attempted to make a prototype of a machine that rolls reemay over greenhouse crops on cold nights and removes it on warm mornings. The arduino based control unit works well. The physical part of the machine did not work.

By October of 2024 I had a ¼ scale model of the Reemay Robot working well in my yard. The electronic controls, motor, and power system all worked well. The model I made didn’t take into account a few details that would prove fatal.

By the Spring of 2025, after 3 attempts at the farm and several follow-up small scale revisions at my shop, I gave up trying to make the mechanical part of the Reemay Robot work for the purposes of this project. However, I continue to believe that I am close to something that will eventually work. Because the details I overlooked in between developing the prototype in my shop and integrating into a greenhouse on the farm are important, documenting this failure is worthwhile so that others can benefit in their own attempts.

The first problem encountered in the attempt to move from the shop to the greenhouse was that the Reemay Robot was located at one end of the large roll of reemay. This meant that the bulk of the equipment had to squeeze into the small space along the low, tapering side of the greenhouse where there isn’t much room. Because we were working in a greenhouse with planted crops, and the crops were planted right to the edge of the greenhouse wall, the location of the equipment along one side of the greenhouse was a problem. Furthermore, since the roll of reemay deployed itself along the top of some wooden rails, there was an additional problem of “tucking in” the sides of the reemay along the edges.

The broad solution to the problem of the small space at the side of the greenhouse is to locate the power and driving equipment of the Reemay Robot in the center or top of the greenhouse, where there is plenty of unused space. This would require a re-design of the rolling mechanism, and several possible schemes for this were proposed by the farmers and volunteers on the project.

To solve the “tucking in” problem, we tried mounting a strip of reemay down the edge of the greenhouse that was permanently installed and overlapped the rolling piece of reemay. This solution was rejected by the farmers, who found that it interfered with cultivation and harvesting of the edge rows.

The original model for the device is the automated rollers that greenhouses have for lifting a side curtain in hot weather. It is possible that a different approach could work. For example, one proposal is to roll and unroll the reemay in the air above the crops. This would solve the “tucking in” problem by avoiding the use of rails altogether. However, the high tensions required to keep 30-50’ of reemay in the air would make it necessary to sew reinforcement strips into the reemay. One of our self-imposed constraints was to not extensively modify the reemay– it is devilish to work with as it tears easily. It is important to remember that for a Reemay Robot to work well from season to season and greenhouse to greenhouse it must be able to be commissioned and de-commissioned quickly and easily to accommodate the seasonal use patterns for production greenhouses. Also reemay wears out after a few seasons. The desire for fast seasonal deployment and periodic reemay replacement probably disqualifies any design that requires sewing on a 50’ piece of reemay.

In general, rolling and unrolling the reemay around a moving rotating rigid core, which mimics the common roll-up sides found on many greenhouses, did not work well with reemay rolling around a PVC core in a horizontal orientation. The reemay often bunches, creating random steering errors which are difficult for an automated system to correct. I was able to get several geometries working consistently in my shop at ¼ scale, but all of them failed in the full-scale greenhouse where more fabric, larger catenaries (droops between supports), and longer roll-outs where errors could multiply all contributed to this frustrating result.

By Spring of 2025 it was clear that the Reemay Robot was not going to work due to mechanical problems, and the project was concluded as a partial failure. The electronic and power systems worked consistently and well, and, as documented, can be used either by farmers wishing to power a roll-up ventilation flap, or by anyone who in the future takes on the mechanical problems.

The documentation of the Reemay Robot is complete save for editing and I’m in the process of uploading it to the Farmhack website.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Photo by Peter Schnell

Photo by Polina Volfóvitch

Photo by Polina Volfóvitch

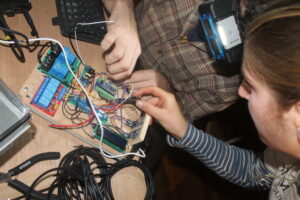

Workshop 1:

Because it is ambitious to propose to teach someone about microcontrollers and complete a real project with them in one day, we tried to stack the odds in our favor for the first workshop. We stacked the odds in the following way: 1. Held the workshop at my house, with a fully equipped shop downstairs for solving mechanical problems, as well as a full electronics shop with piles of spare parts. 2. My house also has plenty of workspace and an industrial kitchen for feeding a horde of people. 3. I did a lot of preparation, pre-assembling parts and pre-soldering leads and connectors so that the farmers at the workshop could assemble things quickly and concentrate on the electronics and computer code rather than the mechanical aspects of each project. 4. Chose 4 farmers for the workshop who proposed to complete projects either the same as or very similar to the Grainbrain and/or Reemay Robot (electronics part) so that there would be fewer surprises during the day.

There were 4 projects: 1. A Grainbrain ; Here And There Farm, Andrew Dixon 2. An integrated greenhouse controller for a greenhouse with a . earthpipe heating system, roll-up sides, and gable ventilation; Duck Hollow Farm, Chris Wilson. 3. A device to monitor, control, and log conditions inside the seed vault of a seedbank; Freed Seed and Ivory Silo Farm, Bill Braun. 4. A controller for a large industrial herb dryer, Town Farm Tonics, Berry Hill Farm, Adam Davenport, Mike Gula.

I did all the ordering of parts and mechanical preparation. Jaden Passero, a computer science BS and school teacher, was the other instructor at the workshop and did a good job of thinking through how to share coding with the farmers. Jaden devised a way of helping the farmers write code by creating a library of functions. The functions in the library can be used with or without understanding the code inside them.

4 Students from Olin College came to the workshop as volunteer instructors: Peter Schnell, Anna Holbrook, Arianne Fong, and Tane Koh.

Anni Schmidt attended as a volunteer instructor but got recruited by the cooks, Derek and Polina, to help cook lunch and dinner for all the others.

Olin Professor Allessandra Ferzoco, her 5-year-old, Chris Yoder, James Davis, and Zeno Schwebel attended as participants/helpers without a project of their own.

The workshop was a success. We spent the morning assembling the parts and learning the basics of electronics, soldering, wiring, and testing. After lunch we broke out the computers and wrote code, loaded it into the microcontrollers, and got the projects running. The farmers (and their helpers) left with ready to use projects which they can integrate into their farms. Two of the farmers had some coding experience and breezed through the code section of the workshop. Two of the farmers lacked coding experience and were a little cross-eyed by the end of it. Although the coding is confusing for some, it is by far the easiest aspect of these projects to seek help with online, as there are tons of online resources as well as forums where volunteers just fix and write code for others at no charge. Most important, the workshop familiarized the farmers with the language and concepts of microcontrollers, which enables them to use the online resources in the future.

After the workshop I solicited comments and feedback from the participants and received this comment from Andrew Dixon:

The workshop ended with a sit-down dinner for 20 people, as much of a success as the workshop. A deep "thank you" to everyone who participated: The farmers who stretched to learn a new skill, the assistants and volunteers who generously shared their time and expertise, and the cooks and hecklers who made the workshop colorful, exuberant, and delicious.