Final report for OW19-339

Project Information

The American sheep industry has seen a steady decline in national sheep numbers dropping from a record 56 million sheep in 1942 to 5.23 million in 2017. A dramatic increase in production efficiency is critical to the future success of the sheep industry. Technologies like electronic identification (EID) tags and genomic testing have been profitably adopted by other livestock industries. We worked with a group of 5 California sheep ranchers to demonstrate and evaluate the economics of how information from both EIDs, and a targeted sheep genotyping panel could be incorporated into commercial sheep production systems. These 5 ranchers participated in the project by allowing researchers to place EID's in the ears of their rams and a sub-sample of lambs; tissue samples were taken from the animals that received EID's. Ranchers also provided an overview of their operation, including a discussion of current management practices and past use of EID's in their flock. Working in partnership with the largest sheep processor in California, Superior farms, tissue samples were submitted to their new genetic testing program, Flock54. Flock54 is a targeted genotyping panel for the sheep industry for pedigree assignment and marker-assisted selection. Lambs from three of the ranchers were sold to Superior Farms for finishing and harvest; data on carcass characteristics was collected using a camera grading system for a portion of the lambs sold to Superior. Genomic data was used to determine parentage and for genetic evaluations. Costs and benefits associated with the adoption of both EID and DNA testing was evaluated. The collaborating ranchers, Superior farms, UCCE specialists and county-based advisors worked collaboratively to plan, design, implement and monitor the project. Like many projects, COVID forced us to alter our outreach plans. Thankfully all the tissue samples and EID tags were placed before quarantine measures were in place. We had originally planned to hold field days and meetings to share research findings. As this was not possible, we took advantage of other outreach opportunities including a risk management workshop targeted at sheep producers, the California Wool Grower's Association meeting, and the American Sheep Industry conference.

The broad goal of this study is to evaluate the benefits and challenges of adopting EID and DNA-based information in the California sheep industry. Adoption of these technologies is one step towards the increased use of information to improve production efficiency, which is currently needed to sustain the sheep industry in California and nationwide.

Specifically, we seek to:

1) Document the current operational costs and records maintained by the five cooperating sheep ranchers at the start of this project (pre-implementation)

2) Work with collaborating producers to place EIDs and collect DNA samples from rams and lambs

3) Collect weaning weight data and other on-ranch phenotypes where feasible, and document the expenses associated with collecting these phenotypes

4) Collect processing, carcass, and camera grading data from Superior Farms on the lambs selected under objective 2

5) Genotype the DNA samples from the rams and 2,500 lambs with the Flock54 genetic test, determine relationships among individuals, and between phenotypes and genotypes

6) Utilize the information collected in this project to quantify the economics of using EID technology in sheep management

7) Assess the value of genetic testing in commercial sheep flocks based on economic analysis of projected positive change scenarios from selecting genetically superior rams based on the genotyping and phenotyping results obtained in this study

8) Share outcomes and findings with California sheep producers through three on-ranch workshops and publications that demonstrate the project’s findings, namely the utility and potential value of EID technology and genetic selection as a flock improvement tool.

Tasks will be performed by the following parties:

- UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisors – Julie Finzel, Rebecca Ozeran, John Harper, Morgan Doran, Dan Macon

- UC Cooperative Extension Specialists – Tina Saitone and Alison Van Eenennaam

- California Woolgrower’s Association representative – Erica Sanko

- Superior Farms

- Participating producers:

- Freddie Iturriria – Bakersfield (Kern County; Finzel) 10,000 + ewes

- Frank Iturriria – Bakersfield (Kern County; Finzel) 5,000 ewes

- Ryan Indart – Clovis (Fresno County; Ozeran) 3,000 ewes

- Ryan Mahoney – Rio Vista (Solano County; Doran) 5,000 ewes

- Jaime and Robert Irwin – ClearLake Oaks (Lake County; Harper) 4,000 ewes

|

Table 1. Timelines and Responsibilities |

||||

|

Task |

Responsible Party |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

|

Team meeting at Superior farms to meet, discuss, and go over project logistics |

1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 |

X |

|

|

|

Ear notch and EID rams |

1 and 5 |

X |

|

|

|

Ear notch and EID market lambs, collect production data on farm |

1 and 5 |

X |

X |

|

|

Ear notch and record dead lambs |

5 |

X |

X |

|

|

Weigh market lambs at slaughter and collect carcass trait data |

4 |

|

X |

X |

|

Write-up findings and publish |

1 and 2 |

|

|

X |

|

Conduct educational outreach workshops |

1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 |

|

|

X |

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- (Researcher)

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- - Technical Advisor

- (Researcher)

Research

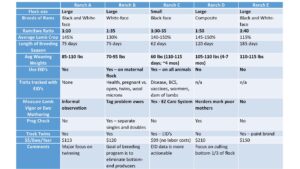

- Exit interviews were conducted with collaborating producers to review production costs of each operation. Costs were documented based on total numbers of sheep in each flock and on a per head basis. Ranch A - Robert and Jaime Irwin; Ranch B - Emigh Livestock (Ryan Mahoney); Ranch C - Dan Macon, Flying Mule Farms; Ranch D - Ryan Indart; Ranch E - Frankie Iturriria (A & M Livestock). See Figure A.

Figure A. - Summary of key characteristics by ranch including number of ewes and average cost per ewe.

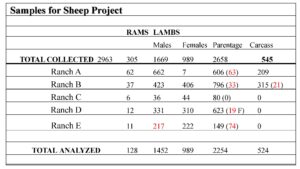

2. At the beginning of the study we had five large-scale, commercial sheep producers in California enrolled in the study. Before all tissue samples were collected and EID's were placed in Freddie Iturriria's lambs, he withdrew from the project. One of our researchers, Dan Macon, is also a sheep producer and graciously agreed to take on a dual role of researcher and sheep producer. Tissue samples were collected and EID tags placed in rams and a sub-sample of lambs from each flock. Number sampled per flock varied and is summarized in Figure B. Breed of ram was recorded. This study focused on rams used in the 2019 breeding season and lambs harvested in 2020. Tissue samples were from docked tails, ear notches, or All-Flex tissue sampling units (TSU). Fresh tissue samples were placed in sealable plastic sample bags and frozen for transport to Superior Farms. All-Flex TSU's include a preservative liquid and do not require refrigeration. The sheep producers are located across California in Lake, Solano, Placer, Fresno, and Kern Counties. The UCCE Livestock and Natural Resources Advisor representing each county worked closely with the producer(s) in their county to assist in the placement of the EID tags and the collection of the tissue sample.

Figure B. Number of rams and lambs sampled per flock

3. Infrastructure needed to collect phenotypic traits like birth weight and weaning weight was largely not available to producers. Data collected on phenotypic traits was limited to carcass traits collected at harvest.

4. Superior Farms collected quality and yield grade data on a portion of the lamb carcasses processed in their plant. Carcass data was not available for all lambs processed at Superior due to a miscommunication between researchers and Superior Farms. Not all lambs were processed at Superior. Ryan Indart and Frankie Iturriria opted to market their lambs elsewhere.

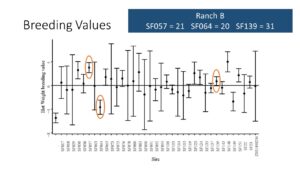

5. All animals that have EID tags placed in their ears also had a sample taken via ear notch, AllFlex TSU or tail dock for DNA testing using Flock54. Flock54 genotypes were used to determine relationships among individuals, and between phenotypes and genotypes. Estimated breeding values were developed for flocks that processed their lambs at Superior (phenotypic data was available to complete the calculation). See Figure C.

Figure C- Ranch B (Emigh Livestock) Estimated Breeding values were developed from lamb hot weight carcass data collected at the Superior Farms packing plant; presented as Estimated Breeding Value by sire. Shorter lines indicate sires with more offspring and increased accuracy of EBV calculation.

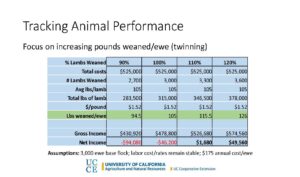

6. (&7) A cost-benefit analysis comparing the cost of EID and genetic testing to projected positive change scenarios is in process. One scenario in which EID's could be used to track individual animal production and the potential benefits (Figure D). In addition, a more detailed cost/benefit analysis is being developed and will be presented on an ASI webinar on July 12, 2022.

Figure D - Potential benefits of using EID's if applied to the objective of increasing lbs of lamb weaned per ewe.

8. The original outreach design called for three on-ranch field days to be held in the first quarter of 2021 to present the results of this project to producers and allied industry. Like many research projects, COVID forced us to alter our outreach plans as we were not able to hold the three field days. Alternatively we utilized other meetings/events targeted at sheep producers. These events were a risk management workshop, the California Wool Grower's annual meeting, and the American Sheep Industry annual meeting. We also redirected some funds towards the development of a website to showcase our preliminary findings. http://rangelands.ucdavis.edu/genetic-improvement-and-electronic-id/

The first phase of test results from Flock 54 were received in August 2019. Most producers in the study cull rams in April/May before the breeding season starts (mid-May for most) and to make room for new rams purchased at ram sales that spring (April-ish). The results were received too late for a producer to use them to make decisions for the next breeding season. Parentage information needs to be returned within a window that facilitates selection for next lamb crop. Similar to results from studies completed in commercial beef cow/calf herds, the economics of genetic testing is not sustainable on a large scale. We expect genetic testing to be an important tool for purebred producers (primarily rams). Further the Flock 54 program is not the appropriate test for determining genetic markers to support the development of Estimated Breeding Values (EBV's). The National Sheep Improvement Program (NSIP) or Sheep Genetics USA would be more appropriate programs.

The presentation given at the American Sheep Industry conference in San Diego, CA in January 2022 is available at the link below. The presentation includes numerous figures summarizing the data analysis and results.

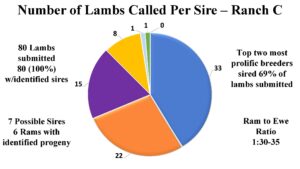

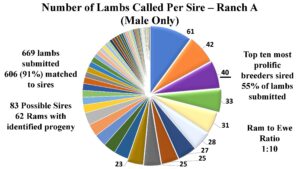

The parentage results for Ranch C (Macon) , D (Indart) and E (Iturriria) (Figure E) followed common trends seen in similar beef cattle studies where a small number of sires produce a large percentage of the lamb crop. Ranches A and B had a lower ram:ewe ratio (Figure A) which resulted in some dilution of this effect (Figure F). One potential explanation for this is the increased competition among rams during breeding season. Ranch E had the greatest number of rams for which parentage was not identified. We believe this was caused by the use of some clean-up rams later in the breeding season that were not tissue sampled for Flock 54.

Figure E - Number of lambs per sire for Ranch C (Indart)

Figure F - Number of lambs per sire for Ranch A (Irwin)

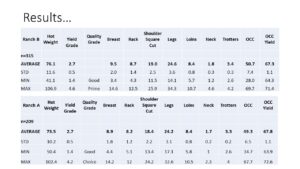

A Principle Component Analysis (PCA) plot was completed for each ranch and between ranches. Slide 12 illustrates some of the genetic variation within flocks from Ranches A, B, and D. Of interest, Ranch B produces Rambouillets, a wool breed, while Ranches A and D focus more on meat breeds. Despite the genetic difference in lambs from Ranch A and Ranch B, when their carcass traits are considered, the final consumable product is quite similar. Figure G.

Figure G - Results from carcass measurements of lambs from Ranches A (Irwin) and B (Emigh). Ranch C (Macon) sold his lambs to Superior Farms, but carcass measurements were not collected at the plant. Ranches D and E (Indart and Iturriria, respectively) did not sell their lambs to Superior Farms and as a result no carcass measurements were collected.

Before the project there were varying levels of EID use among the producers on this project. The producer summary in Figure A provides a snapshot. Ranch A had been using EID’s, but wasn’t using the EID’s to collect data on their flock. Ranch B successfully used EID technology to reduce footrot and the overall health of their flock, along with increasing their lambing percentage 30%. Ranch C, a small flock producer, saved time and money by switching to EID’s and away from a system that required 3 types of ear tags and working the lambs twice at weaning (see link below). Ranch D was interested in the technology, but had not yet invested. Ranch E used only scrapie tags on a small portion of their flock; all flock production was tracked with paint brands or ear marks.

Ranch C cost study of switching to EID's - https://ucanr.edu/sites/Livestock/files/294788.pdf

Citing the experience of both Ranch B and Ranch C, the value of EIDs is seen when the individual animal performance data is used to make better-informed management decisions towards clear goals. In the case of Ranch B, when they first started using EIDs they identified a number of traits they felt it was important to track. After they started processing lambs, they realized the data collection was taking up to 5 minutes per lamb. This level of data collection was not practical for their operation. In response, Ranch B chose three traits to focus on: footrot, twinning rate, and wool microns. This system created a significant reduction in foot rot and, as previously stated, a 30% increase in lamb crop. For Ranch C, switching to EIDs cost slightly less than the previous system of three types of ear tags. Ranch C was already tracking individual animal performance data on their flock and had seen progress towards their identified goals, but switching to EIDs also saved them time and has proved to be a more efficient and practical system for their small flock operation.

One of the common challenges cited when discussing the use of EIDs with large flock producers is the potential cost of the equipment and labor versus the financial benefit to the business. For example, if placing an EID in the ear of each lamb requires 5 seconds per lamb, for a 3,000 ewe flock with 100% lamb crop that could mean an additional 4 hours of labor. Given the cost of the tags ($1.00/EID at the time we purchased the tags), the reader ($2,200), and the labor, producers want to know they are making an investment that will not only pay for itself, but also bring a positive return to the business.

Another common challenge cited by producers is the logistics of using EID systems in the field. In speaking with one producer, he voiced the concern that producers are already short on time. If they think a new practice will require more work or more time, they will often choose to keep management unchanged rather than make some changes that might take more time, but would increase their income. This is a fundamental issue we need to address when working with producers and we are just beginning to discuss potential solutions. However, sheep producers are skilled at finding creative ways to resolve issues. Each producer would need to find the best fit for their operation. Once the EIDs are in the ears of the lambs and the rest of the flock, the next questions are: what is the best way to collect data on the flock and what data should be collected? We spoke with one producer that stated cost of the reader was prohibitive because on their operation each herder would need a tag reader to track flock data. In other words, they would need at least five tag readers and maybe more.

Perhaps one of the most inciteful comments that described a lack of adoption of EID's among producers was that producers need to want to change. If producers are satisfied with the status of their flock, there is little motivation to implement a new practice to improve the flock. Further, the influence of less objective decision making factors bears discussion. In many instances there are factors impacting decisions about flock management unrelated to flock production traits. These may include family dynamics, emotional attachment to specific animals, resistance to follow culling recommendations and more. For example, one producer stated he had fool-proof way to track twins. He used a hole punch to put a hole in the middle of the ear of all twin lambs at birth. However, at weaning, when it was time to identify replacement ewes and ship the remainder of the ewe lambs and all wether lambs he had trouble following his own guidelines. Specifically, he stated, "When that beautiful 130 pound single ewe lamb comes down the chute, I can't get rid of her." When considered objectively, one 130 pound ewe lamb produces less pounds of lamb per ewe exposed than two 90 pound lambs, however, something about that large singe ewe lamb caused that producer to change his mind. While the term might not be completely accurate, for the sake of discussion, let's call these 'right brain decisions'. Individuals are making decisions based on a gut reaction outside of objective information. It's part of being human. What might be helpful in these situations is to plan ahead and decide that for every 1,000 lambs, 10 'right-brain' decisions to keep or sell can be made (and then find a way to keep a count and resist the urge to deviate from the well-thought out plan).

In the rearview mirror...

This project showed producers, who had never used or seen EID's, how to use them and provided an introduction to what the tag readers look like and how they work. We hope to follow up with a hands-on workshop on how to use a reader. Some of the difficulties we encountered (outside of Covid factors) included scheduling tail collection with producers. Some of our producers were hesitant to have us on site when tails were docked. Instead of tail collection we would collect ear notches, which required processing the sheep an extra time. This added labor and time. Further, it took longer to collect the ear notches than we anticipated. Timing and method of tissue sampling need to be worked into opportunities when sheep are already being processed. This applies to EID placement as well.

This project was a first-step in a series of research projects designed to foster interest and use of EID's in commercial sheep flocks and consider their use in conjunction with genetic testing. There is still work to be done to find practical ways for commercial producers to utilize EID's to support individual animal management. However, tracking individual animal performance has been shown to be effective at moving the entire herd (or flock) towards identified breeding goals in other livestock species (dairy, beef, pork). We know it works, the challenge is finding a way to make it feasible and economical for sheep producers.

Research Outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation Summary:

The journal article is in preparation. We expect to submit before the end of 2022. The webinar, as mentioned in the materials and methods, is scheduled for July 12 and focuses on the costs and potential benefits of using EID's. It is through the American Sheep Industry and should be available for live viewing for WSARE staff. Contact Julie for more information.

To date, we have published two articles on this project in a newsletter format. One was published in the California Wool Grower's newsletter and the second was in the Tulare County Farm Bureau monthly newsletter (neither of these are available online). I was contacted by a reporter for Western Farm Press. The article on the research findings was printed on 3/2/22 and is available at: https://www.farmprogress.com/livestock/sheep-producers-technologize-flock

As previously discussed our outreach plans had to shift due to COVID. As such, we took advantage of opportunities to present at workshops/meetings held by others. These included:

- Risk Management for Sheep Producers. June 23, 2021. Rio Vista, CA. Audience: 15

- California Wool Grower's Association annual meeting. September 2021. Bakersfield, CA. Audience: 25

- American Sheep Industry Annual Meeting. January 2022. San Diego, CA. Audience: 30

Because we presented at meetings organized by other entities we were not able to collect any survey data on impact of outreach.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

We are not currently in the stage of the project where we are conducting outreach events. We are still in the data collection phase.