Final report for SW21-922

Project Information

Wireworms, the larval stage of click beetles (Coleoptera: Elateridae), are a major pest of many crops in the Pacific Northwest and Intermountain regions of the USA. In cereals, the foundational crops of the region, prophylactic neonicotinoid seed treatments are presently the only available insecticides to control this pest. Neonicotinoids, however, do not reduce wireworm populations and often fail to protect the crop. Our producers are in dire need for effective alternative management options that fit their regional agricultural practices and that contribute to soil health and sustainability of our agricultural production systems. Moreover, the lack of data on economic losses to wireworms limits agricultural extension expert ability to develop recommendations regarding economic injury levels and action thresholds for this pest in cereals. To address these shortfalls, through a series of on-farm trials and follow-on evaluations, we propose to: i evaluate the effectiveness of brown mustard rotation, and a newly developed concentrated brown mustard seed meal extract, in reducing wireworm damage, ii examine impacts of adoption of these treatments on several soil health parameters, iii develop an early detection method for predicting and estimating economic loss to wireworms, and iv develop extension educational materials for wireworm damage detection, management, and farm profitability implications associated with adoption of these wireworm management strategies. Objectives 1 and 2, as well as the yield aspects of profitability calculations, will be achieved through setting up on-farm research plots in each of the 4 to 5 fields in northern Idaho, southeastern Idaho, and eastern Washington. Farm-scale aerial imaging combined with high resolution wireworm count and yield data will be used to determine the relationship between yield and wireworm pressure at a field scale. This project will result in development of decision-making guidelines and ecologically based pest management tactics that can be cost-effective, and are environmentally benign, sustainable, and most importantly, applicable to cropping systems across the PNW and elsewhere. Findings from this study are of great interest to cereal producers in the PNW and Intermountain West regions. In addition to Idaho and Washington, our findings will be communicated to producers in Oregon and Utah and Montana, with support from Extension specialists in each of those states (see letters of support).

Objectives

Objective 1. Examine brown mustard, its seed meal and a newly developed concentrated extract in reducing wireworm damage to spring wheat. (Research)

Objective 2. Evaluate the impact of brown mustard manure and its products on soil health parameters, (Research)

Sub-objective 1: Quantify the impact of the green manure, seed meal, and concentrated seed meal extract on soil microbial community abundance and structure.

Sub-objective 2: Determine the potential impact of the green manure and seed meal applications on local entomopathogenic nematodes.

Objective 3. Determine yield effects due to wireworms at the field scale and estimate farm profitability implications of wireworm damage and adoption of the wireworm management strategies in Obj. 1. (Research)

Objective 4. Disseminate findings to stakeholders and promote adoption of successful IPM tactics in affected fields across the region. (Education/Extension)

Table 1 presents timelines for various research and extension activities and the major milestone of this project. Objective 1 includes late-summer/fall planting and incorporation with evaluations harvest extended into spring and summer of the subsequent season. Therefore, two field season replicates are expected to be completed by the end of project in March 2024. Similarly, the field experiments outlined in Objectives 2 and 3 are expected to be completed in two field seasons (2021-2022 and 2022-2023) However, laboratory evaluations for objective 2 may continue into winter 2024. Threshold developments and estimates and the development of an online calculator of economic losses will be finalized by March 2024. Extension activities will continue throughout the life of the project. All co-PIs have extensive experience with the type of research proposed here, and two graduate students hired for the project will work under their supervision in Idaho. By staggering the experiments over time, we expect to complete these objectives within the three-year time-frame. Research and extension manuscript preparations are expected to be initiated at the end of the second year and completed within the proposed time-frame.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

Research

Wireworms are key pests of the Pacific Northwest cropping systems resulting in significant losses annually. We hypothesized that brown mustard (Brassica juncea) green manure, its seed meal, and concentrated extract can reduce wireworm populations and subsequent crop damage due to the biocidal effects of their glucosinolate compounds. This hypothesis was developed based on our initial data, which demonstrated the efficacy of brown mustard concentrated extracts can be as high as 70% in the greenhouse. As a part of this project, we will also evaluate any potential effects of mustard and its products on the soil microbial community and the beneficial indigenous entomopathogenic nematodes. Yield effects due to wireworms will be determined, and economic analyses of the evaluated management practices will be conducted by the end of the project.

Objective 1- examine the efficacy of brown mustard, its seed meal, and a newly developed concentrated seed meal extract against wireworms: Trials are being conducted in 5 experimental plot areas in dryland fields located in southern Idaho (3), northern Idaho (1), and eastern Washington (1). All five plot areas have been monitored for the presence of wireworms. Limonius californicus (southern Idaho) and L. infuscatus (northern Idaho and eastern Washington) were the most abundant wireworm species. One of the initial field sites in Ririe had to be removed since enough wireworms were not present. That site was replaced with an additional plot area in Arbon Valley in southeastern Idaho.

Prior to field applications, we demonstrated the effect of brown mustard products on wireworm survival in the absence of environmental stress. For that, we performed a series of greenhouse experiments between 2020 and 2022. Experiments were conducted in square plastic pots (10.16 ´ 10.16 ´ 12.7-cm (W´ L´ H)) filled with 70% sand and 25% peatmoss. The sugar beet wireworm (Limonius californicus) was the target pest in these experiments. The nine treatments pertinent to the field trials included: 1) brown mustard soil-incorporated plant tissue; 2) canola soil-incorporated plant tissue as control; 3) brown mustard seed meal applied at the rate of 8.9 t/ha (8 g/pot); 4) brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract applied at the rate of 2.2 t/ha (2 g/pot); 5) brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract applied at the rate of 3.3 t/ha (3 g/pot); 6) brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract applied at the rate of 4.5 t/ha (4 g/pot); 7) neonicotinoid seed treatment (CruiserMaxx); 8) non-treated control and 9) non-treated no-wireworm control. Treatment 9, non- wireworm control, was added in the experiment to evaluate the germination rate of planted wheat seeds by excluding wireworm disturbance and excluded from statistical analysis due to 100 percent germination. This study was conducted in three time-blocks, with eight replicates per treatment in each time-block (a total of 24 replicates/treatment). Brown mustard (Brassica juncea) and canola (Brassica napus) were planted in pots eight weeks before starting the experiment. At flowering, plants were chopped and mixed into the soil. At the same time, seed meal and concentrated extract of brown mustard were added and incorporated into the soil for respected treatments. All pots were sealed with parafilm for 24 hours. The applied rates were selected based on seed meal efficacy studies in other pest systems (Dandurand et al. 2017). However, since the brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract is a newly developed product, we tried three applications rates. Pots were arranged in a completely randomized design. Wireworm mortality was recorded after four weeks.

Field Study and Treatments: There were eight treatments planned in each location (or plot area; there are now three plot areas in Arbon Valley). Treatments included: 1) winter fallow followed by CruiserMaxx-treated spring wheat; 2) winter fallow followed by non-treated spring wheat; 3) fall brown mustard (Brassica juncea) followed by non-treated spring wheat; 4) winter canola (Brassica napus) followed by non-treated spring wheat; 5) brown mustard seed meal at the rate of 37.8 lb/plot followed by non-treated spring wheat; 6) brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract at the rate of 2.5 gal/plot followed by non-treated spring wheat; 7) winter fallow followed by brown mustard concentrated seed meal extract at the rate of 2.5 gal/plot followed by non- treated spring wheat; and 8) winter fallow followed by Teraxxa-treated spring wheat. Individual plots are 10 ft by 20 ft in size, arranged in a randomized complete block design, with four replicates per treatment. Due to the volume of the needed concentrated extracts, the compound was prepared and shipped from Mustgrow Biologics Corp. Wireworm numbers were estimated in each plot before planting by using solar bait traps (Rashed et al. 2015). Except for one plot area in the Arbon Valley location, winter canola and brown mustard were planted in the first week of September 2021 at the rate of 12 seed/ft in 1-1.5-inch depth (due to the lack of moisture). Brown mustard concentrated extract and seed meal were applied on selected plots in early November 2021. Planted mustard, canola, and applied treatments were incorporated into the soil within two hours after application using a 25-ft disk cultivator. A 2-week interval between extract application and seeding was required to prevent phytotoxicity, so plots were planted with spring wheat during the latter part of May 2022. CruiserMaxx- treated seed and Teraxxa-treated seed will allow us to compare the effects of seed treatments with mustard products on wireworm mortality. Broflanilide (Teraxxa) is a newly registered insecticide in cereal crops (2021) against wireworms, with the suggested mortality effects of more than 90%. The wireworm population were re-evaluated in early June after completing planting operations. Wireworm count, stand count (number of plants), and yield were used to compare treatments.

For 2023, locations were modified following the change of project leaders. The Arbon Valley locations were not continued and in place, sites were added in Moscow, ID and Latah, WA in addition to existing trial locations in Kimberly, ID and Asotin, WA. Oilseed crops were seeded in May of 2022 and terminated in August using discing to a depth of 4 to 6 inches. Seed meals and extract were applied 2 weeks prior to seeding in the spring of 2023. Rather than different timing for the extracts, the extract treatments were modified to incorporate three rates of the material, including 5, 10 and 15 gal/A. Immediately after application of the seed meal and extracts, the products were incorporated by discing to a depth of 4 inches. Spring wheat will be seeded into these plots and measurements of wireworm, microbial activity and yield recorded as described for 2022.

Objective 2- The impact of brown mustard manure and its products on soil health parameters: We proposed two sub-objectives to examine the effects of mustard green manure and extracted products on soil microbial community (Sub-objective 1) and local entomopathogenic nematodes (Sub-objective 2).

In Sub-objective 1, soil samples from experimental plots in all four locations were collected within two weeks of treatment applications in the fall of 2021 to evaluate the immediate effects of mustard products on the resident microbial population. Additional samples were collected from each treatment in the spring of 2022 at the same locations following spring wheat to determine the residual effects of mustard products on microbial communities within the subsequent crop. The second-year sampling was conducted in the spring of 2023 two weeks after treatment application and just prior to seeding spring wheat. Samples were again collected from within the subsequent spring wheat. In each plot, ten core soil samples were collected and homogenized and were lyophilized and stored at -80 ºC. Subsamples were weighed and prepared for phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) and neutral lipid fatty acid (NLFA) analysis. All of 2021/22 samples have been analyzed and a summary of that data will be reported here. Spring 2023 samples have had pH and percentage of moisture data collected. PLFA and NLFA analysis on spring 2023 samples is in progress.

Sub-objective 2, the impact of mustard product applications on beneficial entomopathogenic nematodes was assessed. Two soil samples were collected from each plot from each plot using a 6-inch augur two weeks after incorporating mustard products into the soil in the spring of 2022 before planting the spring wheat. Soil samples were mixed, a subsample of 250 g of soil was placed in a plastic container, and five waxworms were placed in each container to trap nematodes. After 3 days, dead waxworm larvae were transferred to White traps (White 1927), consisting of one 25 mm petri dish containing wet filter paper inside a large (10 cm) petri dish filled with water to recover nematodes from waxworm cadavers. The number of infective juveniles recovered from a single waxworm in 1 ml suspension was counted, and the average of nematodes recovered was used to estimate the nematode population in each experimental plot in relation to the non-treated control plots.

Objective 3- Determine yield effects due to wireworms: In year 1, a fixed-wind unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) equipped with a high-resolution RGB camera was flown at 80 m height over a 15-acre section of fields which we have established our experimental plots. The captured RGB images by UAV flights were mosaicked and georeferenced for visualization at field scales (Figure 1). In addition to RGB images, reflectance images were also generated based on multispectral sensor information to compute the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). Moreover, satellite images at 10-meter resolution were downloaded and compared with UAV-based images to explore optimal spatial solutions for the project. Our large field-scale evaluations had to be revisited due to unexpected challenges. The first challenge was the extreme heat and drought stress that Idaho dryland production suffered from in 2021, which prevented us from obtaining yield records (yield monitors were unable to accurately record yields below 10 bushels/acre) or characterizing wireworm damage (from drought stress). Most importantly, since the arrival of Teraxxa in the market, nearly all planted small grain acreage is now treated, forcing us to revisit our approach, focusing on obtaining data from plot experiments. We used a 5 x 20 (4 untreated and four treated with fipronil, an insecticide with high efficacy against wireworms) to estimate the economic loss in fields infested with wireworms.

In our mustard plots, RGB images were captured by UAVs at 80-meter height. NDVI was computed, and the calibration effort for reflectance images was made to better characterize wireworm damage. In spring and summer of 2022, two more UAV flights were made, three and eight weeks after plant emergence. According to our ecological survey, three weeks after emergence is the peak of wireworm activity. In the 2022 growing season, again in partnership with growers, additional flights were made around 10 weeks after emergence. At the end of this project, a supply chain assessment will be conducted to identify any barriers to the adoption of the treatments, such as commercial availability or access to mustard seed or the extract.

Objective 4- Disseminate our research findings among producers and stakeholders: We proposed a combination of traditional extension activities along with online services. A summary of our 2021-2022 activities is presented below.

Objective 1.

Earlier we demonstrated through greenhouse experiments that the high application rate of the concentrated brown mustard seed meal extract of 4.5 t/ha (4 g/pot) resulted in 68% wireworm mortality compared to the observed 8.7% mortality in non-treated control. Brown mustard seed meal and green manure both caused 33% mortality in wireworms and their efficacy was considerably lower than concentrated than the concentrated extract treatment. The lower application rates of the concentrated extract (2 or 3 g/pot) resulted in 46% mortality. Canola green manure was also included as a negative control and a mortality rate of 16.7% was found for this treatment, which was not statistically different from the non-treated control.

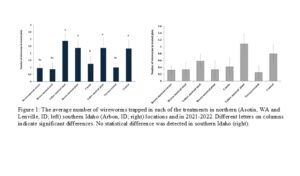

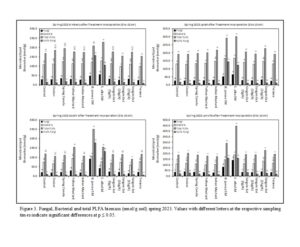

With the observed promising greenhouse results, we proceeded to conduct replicated field studies across Idaho and in eastern Washington between 2021 and 2024. Our 2021-2022 data focused on three field plots established in southeastern Idaho near Arbon, ID, and two field locations in northern Idaho (Lenville, ID) and eastern Washington (Asotin, WA). The northern Idaho and eastern Washington fields were infested with Limonius infuscatus, and the southern Idaho fields were infested with L. californicus. Due to this species difference, these locations were analyzed separately. Figure 1 shows the average number of wireworms collected per trap in both locations. In northern locations (Asotin, WA and Lenville, ID), the number of wireworms was significantly affected by treatments (F9, 78 = 2.138, P = 0.03) (Figure 1). However, treatment application was not effective in reducing wireworm population in Arbon, ID (F10, 121 = 1.014, P =0.435). This lack of significant effect may be due to the low infestation rate in the flied (Figure 1, right) a variable, which could also explain the inconsistent and nonsignificant yield effects (see Table 1).

Grain was collected from all test plots in 2021-22 to estimate yield. A yield summary across all six locations is shown in Table 1. There were very few differences in yield, with none of the treatments being significantly different from those of the non-treated control. However, the brown mustard extract applied in the fall only or both fall and spring resulted in some of the highest yields, as did the canola green manure. Due to wet spring conditions in 2022, the application of brown mustard extracts and subsequent tillage was delayed, resulting in later-than-normal seeding of spring wheat toward the end of May. The late seeding of spring wheat combined with wireworm pressure resulted in very low yields.

Table 1. Average spring wheat yield across all study locations from plots amended with oilseed plant, yellow or brown mustard meal, or brown mustard extract in 2022.

| Treatment | Yield (bu/A) |

| Control (no insecticide) | 20.5 ab |

| Brown mustard (Pacific Gold) | 21.8 a |

| Yellow mustard (IdaGold) | 21.0 a |

| Spring canola (Empire) | 23.5 a |

| Brown mustard seed meal | 21.3 a |

| Yellow mustard seed meal | 21.8 a |

| Sinigrin extract (fall) | 23.0 a |

| Sinigrin extract (spring) | 17.5 b |

| Sinigrin extract (fall/spring) | 22.0 a |

| Teraxxa control | 20.8 a |

| Average | 21.3 |

| HSD (0.05) | 3.1 |

| CV (%) | 22.6 |

The 2022-23 yield data was analyzed separately. Due to logistic limitations, the southern Idaho (Arbon, ID location was replaced with fields in Cloverland (eastern WA) and Latah Couty (northern ID). The presence of wireworms or treatment did not seem to affect yield. The no insecticide control was not significantly different from Sinigrin extract treatments or Teraxxa-treated seed. Averaged across the northern Idaho locations, only the two seed meal treatments differed significantly, and they were lower yielding, particularly the Sinapis alba seed meal. These treatments were applied in the spring at the same time as the Sinigrin extract treatments and incorporated by discing and a cultivator. Trials were seeded two weeks after incorporation of products. However, it is evident from the yield that there was likely phytotoxicity with these two treatments.

Table 2. Average spring wheat yield across all study locations from plots amended with oilseed plant, yellow or brown mustard meal, or brown mustard extract in 2023.

| Treatment | Yield (bu/A) |

| Control (no insecticide) | 73.7 ab |

| Cruiser Maxx | 75.9 ab |

| Spring canola (Empire) | 77.6 ab |

| Yellow mustard (IdaGold) | 73.8 ab |

| Indian mustard (Pacific Gold) | 75.1 ab |

| Seed meal (Brassica juncea) (2 ton/A) | 60.3 c |

| Seed meal (Sinapsis alba) (2 ton/A) | 51.0 d |

| Sinigrin Extract (5 gal/A) | 76.3 ab |

| Sinigrin Extract (10 gal/A) | 70.8 b |

| Sinigrin Extract (15 gal/A) | 73.9 ab |

| Teraxxa control | 81.8 a |

| Average | 71.9 |

| LSD (0.05) | 8.3 |

| CV (%) | 16.5 |

Objective 2.

Sub-objective 1: Quantify the impact of the green manure, seed meal, and concentrated seed meal extract on soil microbial community abundance and structure.

In Sub-objective 1, soil samples from five experimental plots in three locations (Arbon Valley, Idaho; Asotin, Washington; Lenville, Idaho) were collected within two weeks of treatment application and incorporation in the fall of 2021 to evaluate the immediate effects of mustard products on the resident microbial population. Additional samples were collected from each treatment in the spring of 2022 at the same locations following the establishment of spring wheat to determine the residual effects of mustard products on microbial communities within the subsequent crop. The second-year sampling was conducted in the spring of 2023 two weeks after treatment application and just prior to seeding spring wheat. Samples were again collected from within the subsequent established spring wheat. In each plot, ten soil cores were collected and transported to the USDA Soil Microbial Ecology lab in Pullman, WA. Samples were homogenized and lyophilized before being stored at -80 ºC. Subsamples were weighed and prepared for phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) and neutral lipid fatty acid (NLFA) analysis. All of 2021, 2022 and 2023 samples have been analyzed and a summary of that data will be reported here.

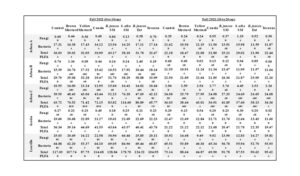

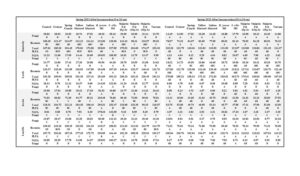

At the fall 2021 plot locations few differences were observed in fungal, bacterial and total PLFA biomass among the control and brown mustard, yellow mustard and canola incorporated plant material (Table 3). This is most likely due to low germination and establishment of these treatments leading to small amounts of plant biomass being incorporated. However, significant differences were observed in the S. Alba seed meal treatment in Fall 2021 (Table 3). Increased fungal biomass in the S. Alba seed meal treatment was seen at Arbon A at both sampling depths and at Lenville in the surface depth (Table 3). Increased bacterial biomass was observed at Arbon C and Lenville, and increased total PLFA biomass was seen at Arbon C and Lenville in the surface depths (Figure 2, Table 3). While not significant, bacteria followed a similar trend of increased biomass associated with the B. juncea treatment at Arbon A (Table 3) and increased total PLFA biomass was observed in both seed meal treatments at Arbon A and Arbon B (Figure 2).

Table 3. Fall 2021 fungal, bacterial and total PLFA biomass (nmol/g soil). Values with different letters at the respective sampling times indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

No significant differences were observed in spring 2022 for any biomarker group at any of the locations at either depth (Table 4). The previously observed increase of microbial biomass within the seed meal treatments in the fall of 2021 had dissipated over winter and were not detected the next spring. Though not significant, a trend of slightly increased microbial biomass was associated with the seed meal and extract treatments. Greatest amounts of total PLFA biomass in the spring of 2022 were associated with the B. juncea seed meal and extracts at Arbon B, Arbon C and Lenville (Table 4). Bacterial biomass was also highest in the spring applied B. juncea extract treatment at Arbon A, Arbon C and Lenville (Table 4).

Table 4. Spring 2022 fungal, bacterial and total PLFA biomass (nmol/g soil). Values with different letters at the respective sampling times indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

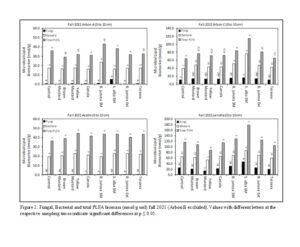

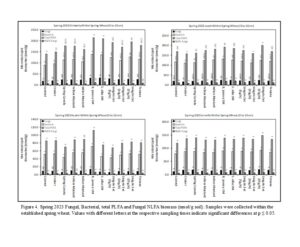

Plot locations in the spring of 2023 included Kimberly, ID; Latah, WA; Asotin, WA and Lenville, ID. Note that the Kimberly (ID) location was excluded from the remaining analyses since it was an irrigated field, unlike other locations. Data are from samples collected at approximately two weeks after incorporation of treatments and again from within the established spring wheat. Because of the observed shift in the fungal community in the previous year, it was decided to collect data from the neutral lipid fatty acid (NLFA) phase during extraction. This additional analysis targets neutral lipids associated with storage lipids in organisms, especially fungi. This allows for confirmation of the fungal biomass in addition to what is represented in the PLFA phase.

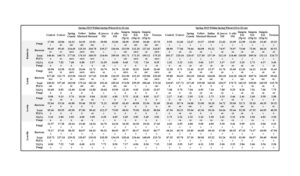

Following treatment incorporation, a prominent trend of increased microbial biomass was observed with the B. juncea and S. alba seed meal treatments. Particularly the fungal communities, but increases were also observed in the bacterial and total PLFA biomass (Figure 3). Significant differences were present in fungal biomass of both the PLFA and NLFA fractions of B. juncea seed meal treatment all four locations in the surface depths. Fungal biomass in the S. alba treatment was significantly greater in the PLFA fraction at three of the four locations and significantly greater in the NLFA fraction at all four locations in the surface depth (Figure 3). Increased fungal biomass was also observed at the 10 to 20 cm depth in the seed meal treatments at the Latah and Asotin locations (Table 5).

Total PLFA biomass was significant in the seed meal treatments at three of the four locations (Table 5). Bacterial biomass was only significantly greater in the S. alba seed meal treatment at the Lenville location but followed a similar trend of increased biomass in the seed meal treatments at all locations in the surface depth (Figure 3). No other significant differences were observed among the control, canola, mustard and extract treatments in both depths at all locations (Table 5).

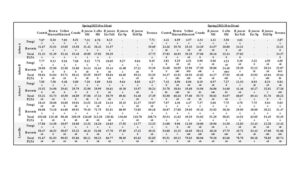

Table 5. Spring 2023 Fungal, Bacterial, total PLFA and Fungal NLFA biomass (nmol/g soil). Samples were collected two weeks after the incorporation of treatments. Values with different letters at the respective sampling times indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

Two weeks after the treatments were incorporated spring wheat was planted. Samples were again collected after the spring wheat had established. PLFA and NLFA data from within the spring wheat showed fewer significant differences than after treatment incorporation. The only significant differences were NLFA fungal biomass at Latah in both seed meal treatments and Asotin in the B. juncea treatment in the surface depth. Additionally, bacterial and total PLFA biomass was greater in the B. juncea seed meal treatment at Asotin (Figure 4). The only significant difference in the 10 to 20 cm depth was for total PLFA in the S. alba seed meal treatment at Latah (Table 6).

Table 6. Spring 2023 Fungal, Bacterial, total PLFA and Fungal NLFA biomass (nmol/g soil). Samples were collected two weeks after the incorporation of treatments. Values with different letters at the respective sampling times indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

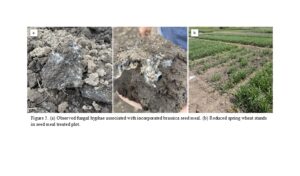

The increase in fungal biomass was also visible in the field within the seed meal treatments at the Lenville location in years 1 and 2, as well as Latah in year two. Visible dense mats of fungal hyphae could be seen associated with incorporated seed meal (Figure 5a). Reduced spring wheat stands were also observed in the seed meal-treated plots at Lenville and Latah (Figure 5b). In addition to completing PLFA and NLFA analysis on the spring 2023 samples, we plan to investigate further the increase in fungal biomass associated with seed meal treatments. Subsamples have been stored at -80 ºC, and we plan to send them off for sequencing to identify the fungal species present.

Sub-objective 2: Determine the potential impact of the green manure and seed meal applications on local entomopathogenic nematodes.

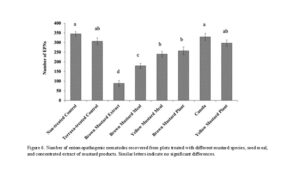

Brown mustard concentrated extract significantly affected the efficacy of beneficial entomopathogenic nematodes in our experimental plots (Figure 6). In plots treated with the brown mustard concentrated extract, significantly fewer nematodes were recovered from the infected waxworms compared to the non-treated control. Canola, yellow mustard green manure, and the insecticide Teraxxa did not have a negative impact on the efficacy of the entomopathogenic nematodes in our experimental plots.

Objective 3.

The wheat yield data obtained in Obj. 1 indicate that there were no statistically significant yield effects from application of most of the evaluated treatments compared to the control, except for the seed meal treatments which has an undesirable and statistically significant yield reducing effect. This effect of reduced yields of about 23 bu/A for seed meal (Sinapsis alba) and about 13 bu/A for seed meal (Brassica juncea) imply that application of these treatments would lead to considerably lower farm profits than not using these treatments, at least in the short term.

For the 2023 – 2024 crop year (June 2023 – May 2024), Idaho Barley Commission Idaho Grain Market Report data show that the average Soft White Wheat price in Lewiston, ID was had average of $6.64/bu. This implies that if a 100-A farm applied the seed meal (Sinapsis alba) prior to planting and realized reduced yields of 23 bu/A, then revenues from wheat sales could be over $152/A (>$15,200/100A) lower than if it were not applied. Similarly, if the seed meal (Brassica juncea) was applied, then revenues from wheat sales could be over $86/A (>$8,600/100A) lower. Given that these seed meal treatments have costs, these treatments appear most detrimental to farm profitability compared to the no treatment control, at least in the short term.

However, the potential revenue and profit implications do not account for potential longer-term economic benefits from use of the studied treatments in cases of substantial wireworm infestation, since all were found to have some efficacy in causing wireworm mortality in the greenhouse studies. Additionally, most of the treatments examined could be incorporated within organic production systems, which may likely have a price premium compared to the conventional wheat price mentioned above, and so the benefit-and-cost considerations would be different for organic relative to conventional production systems.

Objective 4. Our study activities and outputs were communicated to the regional stakeholder via several venues, especially the northern and southern Idaho cereal schools and field days. Funding support through Western SARE is acknowledged in all presentations (one exception of omission error). We also communicated findings through published reports and abstracts.

Research outcomes

Although the brown mustard seed meal and its concentrated extract were effective in reducing wireworm populations in northern Idaho and eastern Washington (with similar trends observed in southern Idaho), the treatments did not cause a significant reduction in any of the microbial groups when compared to the control. The incorporation of canola and mustard plants resulted in microbial biomass levels comparable to the control. The incorporation of mustard seed meals and extracts, in many cases, resulted in significant increases in microbial biomass over other treatments. The most consistent trend at all locations and in all years was the increase in fungal and total microbial biomass associated with the seed meal treatments.

Despite these positive effects on the microbial community, the entomopathogenic nematodes appeared to be significantly influenced by the application of mustard products, and future studies are needed to determine the recovery time of the entomopathogenic nematodes following brown mustard application. The application of mustard seed meal had negative effects on yield due to phytotoxicity. The earlier application of mustard products may help with reducing phytotoxicity and subsequent yield loss. However, earlier in the season, wireworms may not be active in northern Idaho and eastern Washington, which could impact the efficacy of biofumigation against wireworms.

Despite reductions in wireworm populations (and an increase in some microbial activity), the observed variations in yield could not be explained by differences in wireworm numbers and microbial activity.

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

Presentations:

Rashed, A., A. Nikoukar, S. Henricks, & K. Andrews. The challenges and future of integrated pest management of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae). Symposium presentation. Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting, Vancouver, Canada, November 2022.

Nikoukar, A., I. Popova, K. Schroeder, J. Hansen & A. Rashed. Efficacy Evaluation of Yellow and Brown Mustard Concentrated Extract Against Sugar beet wireworm, Limonius californicus (Coleoptera: Elateridae), in Wheat: 81st Annual Pacific Northwest Insect Management Conference, January 2022. Online Oral Presentation.

Nikoukar, A. Integrated pest management of sugar beet wireworm (Limonius californicus). Entomology, Plant Pathology and Nematology Seminar. Moscow, ID, October 2021.

Rashed, A., Aphids and wireworms of the PNW: where they are and how to manage them. Northern Idaho Cereal School, January 2022.

Rashed, A., Pests of Small Grains. Wireworms of the PNW- Where they are and how to manage them. Southern Idaho Cereal School, February 2022.

Randall, J. R., Nikoukar, A., Sadeghi, R., Odubiyi, S., Rashed, A., & Popova, I. The Use of Wireworms As Bioindicators for Monitoring Biopesticides’ Fate in Soil [Abstract]. ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, 2021.

Extension publications

Nikoukar, A., Popova, I., Rashed, A. 2021. Sugar Beet Wireworm (Limonius californicus) Mortality in Response to Yellow and Brown Mustard Green Manure. p. 19-20. In: Dryland Field Day Abstracts: Highlights of Research Progress (eds. S. Crow, B. Schillinger, K. Schroeder, D. Finkelnburg, A. Rashed, S. Philips, and D. Satur). Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Report UI-2021-1.

Nikoukar, A. Popova, I. Schroeder, K. Hansen, J. Rashed, A. 2022. Efficacy Evaluation of yellow and brown Mustard concentrated extract against sugar beet wireworm, Limonius californicus, in wheat. 81st Annual Pacific Northwest Insect Management Conference Research Reports. Pp. 55-57.

Research publications:

Randall, J., Nikoukar, A., Rashed, A., & I. Popova. 2024. The use of Brassicaceae derived pesticide for control of wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae). Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment, 7, 100122.

Nikoukar, A. 2024. Ecology and Management of Wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) in Conventional and Organic Production Systems. Pp. 113. PhD Dissertation Virginia Tech.

Websites

Project website: Wireworm Management System (uidaho.edu)

A. Rashed Laboratory website: Soil Health & Pest Management Practices – Welcome to the Southern Piedmont Entomology Laboratory (vt.edu)

Education and Outreach Outcomes

The results of this project were communicated through conference and grower presentations in regional, national and international meetings. We also presented our findings during field days. In-person methods have been the primary means of communicating results with our stakeholders. We are currently in the process of developing a Wireworm Management System website to provide growers with the latest information on wireworms and wireworm management.

Overall, although the application of concentrated brown mustard products can reduce wireworm numbers, this effect did not result in significant yield increases. Given the cost of implementing mustard products such as brown mustard seed meal and concentrated extract, it is likely not an economically justified approach to managing this pest. Cost-to-benefit analysis is needed to evaluate the feasibility of this application in organic production systems.

- Cultural practices

- Biofumigation