Progress report for SW22-934

Project Information

Wildlife-livestock conflicts, such as depredation by predators, challenge the livelihoods of livestock producers (hereafter, ranchers). Protecting livestock from predators is a complex endeavor, and successful predator conflict mitigation practices require both an analysis of the efficacy of various practices and collaborative information sharing across invested stakeholders. Ranchers typically use an integrated management approach—primarily focusing on animal husbandry and ranch management, while also deploying mitigation practices to reduce depredation risks and lethal techniques when mitigation practices fail, and lethal control is authorized. Mitigation practices include human presence (e.g., range riders), deterrents (e.g., fladry), livestock management, and habitat manipulation, but there is limited scientific information on which practices are most effective and under what scenarios they succeed or fail. Ranchers also lack adequate resources to apply mitigation practices or share knowledge gained through experience. Through a diverse partnership of ranchers, scientists, conservation groups, and agencies with decades of experience with landowner collaborative strategies and predator conflict mitigation practices, we evaluated the effectiveness of range riding across western landscapes with grizzly bears and wolves, hosted opportunities for ranchers to exchange information about mitigation practices, and will disseminate information from our research and exchanges via scientific papers, extension articles, and traditional and novel education and outreach programming. We therefore pursued a co-production approach in what is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive project of its kind to date.

We focused on range riding because this practice is of high utility to ranchers, yet riding strategies vary widely. How and what works best is unclear, inhibiting adoption by more ranchers. Our research described and quantified the types and efficacy of range riding strategies, while rancher-to-rancher exchanges provided opportunities for foundational knowledge from years of rancher experience to be distributed more broadly. Published products will add scientific credibility to the findings and reinforce learning from exchanges through multiple and highly accessible outlets. We provided diverse outreach venues to facilitate new and improved use of predator conflict mitigation practices and add new users; we anticipated ranchers already using these practices would fine-tune their application for increased efficacy, while others would incorporate these practices into their management for the first time. Results of our study helped to create adaptive and integrative predator conflict mitigation practices disseminated to 600+ ranchers across 7+ states.

We used an iterative process to ensure successful implementation to improve sustainable agricultural practices. Information was continuously communicated among team members about the research, outreach, and rancher-to-rancher exchanges, which facilitated incremental changes in co-production processes and in how the practices are implemented by ranchers. This project has and will continue to create transformative change in agricultural sustainability by supporting a community of practice to research range riding across diverse social and ecological contexts in different grazing scenarios. We expect this framework to be applied to other mitigation practices and develop mechanisms for sustainable funding of such practices through NRCS-administered Farm Bill programs. Because we continuously coordinated with NRCS personnel and ranchers about how our research can be applied to decision-making surrounding funding for ranchers, our work helped to establish best practices for predator conflict mitigation that significantly improve sustainable agricultural production through incentivizing the adoption of proactive strategies. Importantly, the work resulted in $22 million for the implementation of the practices.

While some analyses for the research components are still ongoing, so far our preliminary work has yielded these key takeaways:

- Cattle may be adapting their use of high forage availability areas in response to predator activity as a means to reduce predation risk. Whether this stress response is significant enough to impact livestock economics (e.g., reduced weaning weights, reduced cow body condition score, reduced pregnancy rates) will require more research.

- Riders may not meaningfully reduce predator-induced stress and/or pressure in cattle to improve the use of high availability foraging areas, but finer scale analyses (spatiotemporally) may better assess livestock response to both rider and predator activity.

- Rider deployment strategies should remain context-specific and adaptive rather than prescriptive.

- Support the conflict mitigation approaches livestock producers advocate for - cultural and operational context, as well as uncertainty reduction, adaptive management, data collection, and improved coordination/communication are equally important effectiveness metrics for nonlethal tool adoption as effectiveness in reducing direct loss.

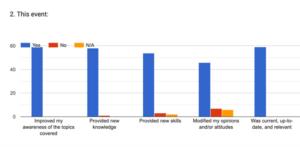

For the education and outreach portion, we have learned the following lessons:

- Building communities of practice amongst diverse stakeholders in conflict reduction can help support information exchange relevant to practice adoption for a host of practices, including range riding

- Engagement of broad networks with effective, science and land-stewards centered communications can support increased knowledge of range riding and its application, and support cross-pollination of ideas within networks, building momentum for practice implementation.

- Landowners and livestock producers maintain knowledge of the land and stewardship practices that are not often captured in scientific research, or elevated for peer-to-peer learning. Incorporating this knowledge is both important for representative applied science, and for diffusion and implementation of practices such as range riding.

- Improve ranch profitability through range riding, a predator conflict mitigation practice that is highly adaptable across diverse ranching operations.

- Coproduce research to evaluate the cost and effectiveness of different range riding strategies across at least seven western states.

- Incorporate data collected by researchers, ranchers, and local landowner groups to accomplish a robust evaluation of conflict reduction strategies.

- Expand and integrate effective range riding strategies with adaptive conflict mitigation programs through rancher-to-rancher knowledge exchanges to support an enhanced quality of life for ranchers, livestock, and wildlife.

- Elevate conservation planning and natural resources management within predator-occupied regions through co-interpretation and dissemination of project results on range riding and other conflict mitigation practices.

- Synthesize research using metrics relevant to livestock production to indicate the value of range riding and other conflict mitigation practices to ranchers.

- Provide data to NRCS to inform the development of new or modified conservation practices to incentivize broad adoption of conflict mitigation techniques.

- Disseminate and amplify the collective experience and knowledge gained through this project by providing highly relevant content through a combination of traditional outreach programming (workshops, seminars) and novel outreach products, including audio, print, and digital platforms.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

The goal of the project was to reduce the financial and social burden of expanding predator populations through the evaluation of range riding practices and information sharing among ranchers about their experience with all predator conflict mitigation practices, leading to more resilient ranches and connected landscapes.

We accomplished the following goals through four project objectives:

- Improve ranch profitability through range riding, a predator conflict mitigation practice that is highly adaptable across diverse ranching operations.

- Expand and integrate effective range riding strategies with adaptive conflict mitigation programs through rancher-to-rancher knowledge exchanges to support an enhanced quality of life for ranchers, livestock, and wildlife.

- Elevate conservation planning and natural resources management within predator-occupied regions through co-interpretation and dissemination of project results on range riding and other conflict mitigation practices; and

- Disseminate and amplify the collective experience and knowledge gained through this project by providing highly relevant content through a combination of traditional outreach programming (workshops, seminars) and novel outreach products, including audio, print, and digital platforms.

Objective 1 focuses on research, while objectives 2-4 are primarily concerned with education and outreach, so they are described in detail in the educational section below. However, all the results and information we learned from reaching our research objectives were applied to the educational objectives. Through objective 3, we worked to ensure the information was accurate and readily available to incorporate into objectives 2 and 4 using an iterative process. As we gained information from objective 1, we tried to incorporate it into the outreach materials, disseminate it at workshops, and discuss it at rancher-to-rancher exchanges. We used feedback from ranchers and other stakeholders about the clarity of information, the relevancy of these findings to their practices, and what other information was needed.

There were several steps to accomplishing our research objective. First, we met with individual ranchers and landowner groups. As part of our existing Conflict on Workinglands Conservation Innovation Grant (CoW-CIG), we met frequently with ranchers and other stakeholders from across the West to understand what value riding provided to them, how best to measure that value, and what methods would be useful and feasible to measure that value. We examined the influence of varied rider activity on 1) annual conflict (combined predator induced injuries and depredation on cattle), 2) annual herd return rates, 3) annual herd pregnancy rates, and 4) chemical indicators of stress in cattle herds (cortisol and thyroid function) in an effort to improve rancher profitability through reducing conflict, enhancing stewardship through an improved understanding of how a rider can reduce cattle stress that leads to indirect losses, and improving overall quality of life for ranchers and their communities by helping to empower operational decision-making. Funding from the Montana Western SARE allowed us to build on that research with the following objectives:

Objective 1. Research Objectives (1-2) and Hypotheses (a. - cvi.)

- Identify whether varied range riding activity alters behavioral indicators of stress in cattle.

As rider intensity, time spent within proximity of the herd, and time riding at dusk, dawn, or at night increase,

a. Seasonal herd vigilance will decrease, and

b. Cattle use of high availability foraging areas will increase.

Although not a deliverable for this grant, the larger Conflict on Workinglands Conservation Innovation Grant (CoW-CIG) also examined the following;

As rider intensity, time spent within proximity of the herd, and time riding at dusk, dawn, or at night increase,

ci. direct losses (depredations and injuries) will decrease,

cii. return rates will increase,

ciii. pregnancy rates will increase,

civ. average herd cortisol levels will decrease,

cv. average herd thyroid levels will increase, and

cvi. average herd body condition scores (cows) will increase.

While we will not be reporting results for all of these hypotheses, we list them here to provide context for data collected, and will share preliminary findings on our cortisol and thyroid analyses (Research Objectives 1civ. and 1cv.).

2. Conduct unstructured interviews with livestock producers to capture the unique operational, environmental, and economic context driving decision making regarding range riding, and to provide important context to our qualitative findings.

Research Objective 1 - Study Area and Data Sources

Study Area

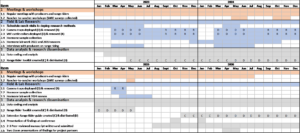

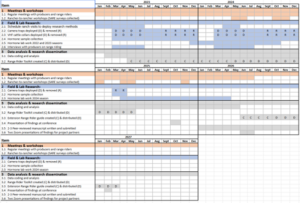

To examine the influence of varied rider activity on cattle behavior, we collected several data streams on rider activity, habitat features and forage availability, predator spatial use, and cattle behavioral activity across multiple operations in Montana, Washington, Oregon, Arizona, and New Mexico from 2022-2024 (Figure 1). In total, we had eight operations participating in 2022, 12 in 2023, and 13 in 2024. All Montana operations are in areas with wolf and grizzly bear populations, whereas operations in the other states were only in areas with wolf populations. Field seasons started in January and wrapped up by early December, depending on the operation location.

Data Sources

Range Rider Data

In grazing seasons 2022, 2023, and 2024, participating range riders completed rider data sheets. We encouraged daily data collection, but to accommodate the time constraints of range riders, we also allowed for weekly data collection (Nickerson_Daily_Rider, Nickerson_Weekly_Rider). Several riders in Washington and Montana also recorded their riding tracks with a GPS unit. Range riders were trained each spring on data collection for both GPS units and data sheets that were provided at the start of the season. Range Rider GPS tracks will be used to compare rider landscape use and proximity to cattle location data (recorded by the rider) and carnivore location data when available.

Rider sheets (n = 1505) were collected during the 2022, 2023, and 2024 grazing seasons and were cleaned and coded for:

- Rider frequency: total rides per ranch-season,

- Mean ride duration: ride duration averaged across all sampled rides per ranch-season,

- Mean proportion of ride time at night: proportion of ride duration from local dusk to dawn, averaged across all sampled rides per ranch-season,

- Predator effort: proportion of total recorded rider time devoted to predator-related tasks defined as checking game cameras, locating predators via telemetry, and hazing, divided by the total duration of each sampled ride, averaged across all rides per ranch-season,

- Livestock effort: proportion of total recorded rider time devoted to cattle-related tasks defined as checking on livestock, providing salt/mineral, fixing fence or other infrastructure, and/or moving the herd, divided by the total duration of each sampled ride, averaged across all rides per ranch-season,

- Mode of travel: proportion of total sampled rides per ranch-season for truck, atv/side by side, horse, and foot, and

- Use of dogs: proportion of total sampled rides per ranch-season where dogs were used (yes/no).

Environmental Data

Environmental data was collected for all three grazing seasons through our producer partners and existing open-sourced data:

- Pasture and allotment shapefiles for each operation were provided by the USFS or participating livestock producers.

- To calculate available forage biomass for each herd, we wanted to restrict availability to represent only areas on allotments that cows were likely to graze. We used distance-to-water and slope as restrictive parameters.

- Surface water availability was mapped using the U.S. Geological Survey National Hydrography Dataset (NHD - USGS National Map, 2024). We retained feature classes representing perennial water sources (NHDArea and NHD Waterbody), spring and tank locations (NHDPoint), but excluded flowlines and stream segments because these features frequently represent ephemeral or intermittent drainages that may not be seasonally reliable. Minimum distance to any water source was retained via Euclidean distance rasters generated in ArcGIS Pro version 3.5 (ESRI, Redlands CA). Cattle grazing areas were then classified across all ranches by limiting grazing areas greater than or equal to 1.5 miles (2414 meters) as is commonly cited in the literature (Valentine, 1947; Hart et al., 1993; Bailey, 2005).

- Elevation data were obtained from the LANDFIRE US_220 Elevation dataset at 30-m spatial resolution (LANDFIRE, 2023). The percent slope was then derived for all operations using the slope tool in ArcGIS. Areas with slopes greater than or equal to 30% were classified as unlikely to be utilized by cattle based on the peer-reviewed literature (Bailey, 2005).

The percent of each allotment rendered unavailable by both distance-to-water and slope constraints was low (~7% on one allotment, but an unclassified water tank was likely present, and no more than 4% across all other allotments. The difference in slopes between the restricted raster and non-restricted was only 0.02-1.2%); therefore, forage availability metrics were calculated for all acres of an allotment, and not restricted by distance-to-water or slope.

Available forage biomass (kg/ha represented by 16-day incremental production estimates at 30-m resolution) within pasture boundaries was quantified using remotely sensed vegetation products (herbaceous production rasters) accessed through the Rangelands Analysis Platform (RAP; Allred et al., 2021). For each area of interest, herbaceous production rasters were extracted and averaged to a single AOI-level production value for each month of the grazing season (mean standing herbaceous biomass). We estimated forage availability at three spatiotemporal scales:

-

-

- Mean standing herbaceous biomass per ranch-month was estimated for each month overlapping dates when cattle were present within each operation’s pastures/allotment(s) following rotation,

- Mean standing herbaceous biomass per ranch-season was calculated by aggregating monthly estimates for the entirety of the grazing season, and

- Mean standing herbaceous biomass per camera-month was calculated using a 30-m buffer at the location of each remote game camera, estimating monthly forage availability, then averaging values across all cameras deployed within each camera cluster for a monthly cluster average.

-

3. Openness metrics were derived from the Rangeland Analysis Platform 10-m vegetation cover product and defined as the inverse of woody vegetation cover (100 − percent tree and shrub cover - RAP). We estimated:

-

-

- Allotment-level openness by averaging values across constituent pastures, and

- Game camera–level openness as the mean value within a 30-m buffer surrounding each camera location.

-

4. Proportion of days per ranch-season with stress-producing temperatures for cattle (Nakajima et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2023; Nielsen et al., 2025) were calculated by summing the proportion of days per ranch season exposed to stress- causing heat exposure and stress-causing cold exposure. For heat exposure, we calculated the daily temperature-humidity index (THI) where daily mean air temperature (degrees Celsius) and mean dewpoint temperature (degrees Celsius) were obtained from PRISM daily climate products dataset (PRISM Climate Group, 2024) and summarized across active pastures. We set our threshold for THI at 22.22 degrees Celsius as is commonly used in the cattle literature (West, 2003). For cold exposure, we calculated effective temperature computed from daily minimum temperatures (degrees Celsius) and wind speed (dm/h) via the nClimGrid_Daily dataset (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, 2024). We set our threshold for wind equivalent temperature at or below 0 degrees Celsius, as some studies have found even higher temperatures to result in measurable chemical stress responses in cattle (Nakajima et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2023).

Predator Data

We collected data on predator locations using three methods: 1) rider observations recorded via rider data sheets (see attachments), 2) data provided by state, federal, and tribal wildlife agencies through data sharing agreements (both wolf and grizzly bear GPS-collar data and wolf density data), and 3) game cameras deployed on grazing allotments/pastures.

- Rider datasheets were cleaned and species detections were summarized by ranch–year. Formal training in wildlife track and sign identification was not implemented until fall 2024 due to workshop scheduling; consequently, rider observations were excluded from predator activity metrics to minimize observer-related bias.

- GPS-collar data for wolves and grizzly bears provided by state, federal, and tribal agencies were spatially filtered to retain only locations within actively grazed pastures, thereby aligning predator exposure metrics spatially and temporally with areas used by cattle. Filtered locations were aggregated across pastures within each grazing season to produce a ranch–year index of predator spatial use/activity rather than an estimate of abundance (total collar locations).

- Wolf densities were provided by agencies or collected via public annual reports. Density data on grizzly bears were not available.

- We deployed 30 motion-activated cameras per operation in 2-3 clusters consisting of 10–15 cameras each (Figure 2). Grid locations were selected in collaboration with producers and range riders to target areas of consistently high cattle use during active grazing periods. Cameras within each cluster were arranged in a radial configuration centered on focal cattle-use areas (e.g., high-quality pastures, water tanks, salt licks, etc.). Cameras nearest the center were spaced approximately 10–30 m from the center point of interest. Additional cameras were positioned along expanding radii (2-4 radii, depending on local landscape conditions) at approximately 100 m from the center point at the first radii point, 250 at the second, 475 at the third, and 700 at the fourth, 925 at the fifth, and up to 1,150 m at the sixth, depending on the number of radii. This approach increased spatial coverage while reducing the probability of failing to detect predator presence within heavily used areas by cattle. Camera groups were relocated throughout the grazing season to correspond with pasture rotations and maintain alignment with active cattle pastures. Cameras were configured with an 18.29m detection distance and a 30-s delay between triggers to conserve battery life and capacity while reducing repeated captures of the same individuals. Because cameras were intentionally placed in areas of high cattle activity (no grid or random design), predator activity inference is limited to within camera groups rather than landscape-wide.

In 2022, we collected data from 240 game cameras across eight ranches, 390 cameras on 13 ranches in 2023, and 420 cameras across 14 ranches in 2024. Camera trap images were organized by unique camera deployment and processed using SpeciesNet (Google, 2026), designed to combine object detection with the species classifier MegaDetector (Beery et al., 2019). SpeciesNet is well supported in recent peer-reviewed literature (Clarfeld et al., 2025), and version 5a used for our analysis has a reported accuracy of 97-98% (Beery et al., 2019). SpeciesNet was run in batch mode on a GPU-enabled high-performance computing environment to generate detection bounding boxes, class probabilities, and predicted labels for each image. To improve accuracy, we used geographic filters, used human review on images with low confidence assignments, and manually validated a small subset of images across predicted classes.

Herd/Operational Data

Operational-level covariates were collected to inform conflict models, both as response variables and as predictors to disentangle the potential effect of both predator and rider activity. Data were collected during the summer of 2025 in collaboration with participating livestock producers and range riders. The following ranch-year metrics were compiled:

- Producer reported predator-caused conflicts by ranch-year: summed injuries and depredations,

- Wildlife agency confirmed predator-caused conflicts by ranch-year: summed injuries and depredations,

- Producer reported return rate by ranch-year,

- Producer reported average pregnancy rate by ranch-year,

- Producer reported average weaning weights by ranch-year,

- Producer reported herd size by ranch-year (used to calculate herd density using aggregated pasture size in acres),

- Producer reported grazing season length by ranch-year (i.e., total days),

- Whether cattle had access to salt on a regular basis by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Whether cattle had access to mineral on a regular basis by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Whether cattle were vaccinated by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Whether operations use low-stress livestock handling techniques by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Whether an operation used artificial insemination or bulls by ranch-year (AI/bulls),

- Whether an operation used growth hormones in calves by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Whether other nonlethal tools or lethal removal was used during the grazing season by ranch-year (yes/no),

- Average calf age at both allotment turn-out and weaning by ranch-year (in months),

- Herd composition by ranch-year (categorical),

- Herd breed by ranch-year (categorical),

- Producer-reported average herd calving date by ranch-year, and

- Producer-reported average herd weaning date by ranch-year.

Although recorded, we did not find significant variation across ranches regarding access to salt (all regular basis), access to mineral (all regular basis), vaccination protocol (all use), herd breed (all Angus or Angus mix), herd composition (all cow-calf pairs with replacement heifers), or use of low-stress handling techniques (all reported yes). Therefore, these metrics were not used in the models but were standardized across operations.

Cattle Behavioral Data

To explore the influence of varied riding behavior on behavioral indicators of stress in livestock, and the potential influence of behavioral stress on chemical and physiological indicators of stress in cattle, we obtained two metrics of the cattle: 1) landscape-use behavior and 2) vigilance.

- Cattle landscape-use behavior was quantified using data from range rider data sheets and deployed motion-activated cameras (see above for camera design and forage availability calculation methods using RAP). Cameras were then classified into low, medium, or high-quality foraging areas based on forage biomass tertiles (lbs/acre) calculated separately for each allotment within each 16-day RAP interval (RAP; Allred et al., 2021). Thus, forage classifications were relative to conditions within a given ranch and time period rather than applied uniformly across the study area. To characterize forage conditions at a broader spatial scale more aligned with average cow traveling speeds while grazing, forage biomass values were averaged across cameras within each camera group to generate a group-level measure of forage availability by date. Camera groups were subsequently classified into low, medium, and high forage categories using the same tertile-based approach.

Camera trap images were processed as described above for cattle classification among other species using SpeciesNet (Google, 2026). Cattle use by camera was organized by date (dates spanning all days at least one camera was active in each camera group), and photos were coded for the total number of cows recorded on that date. Dates with no photos of cows were scored zero.

In 2023, we collected cattle location data by deploying 219 VHF collars/ear tags across four ranches. VHF collars allowed range riders to more easily locate and record cattle locations on rider data sheets, which we hoped would allow for improved cattle location data, but also a comparison between riders with and without VHF assistance. We prioritized collaring lead cows at the three operations, with a minimum of 20% of each herd receiving a collar or ear tag. Cattle were collared at the start of the season with help from ranchers, riders, and their employees. We had a collar/tag failure rate of about 30% by the time units were removed in October and November of 2023. However, we found from communication with range riders that finding cows with at least 20% herd coverage was more than sufficient (continuously hearing 3-6 cows at once). For that reason, we only collared 10% of each herd in 2024 to simplify our process and stay within the number of remaining functional units. We deployed about 150 VHF collars/tags on three of the same ranches last year, adding a new producer in Washington state. We did not place collars on cattle in Oregon last year. Collars and tags were removed during the months of October and November with a similar failure rate of about 40%.

Unfortunately, rider telemetry data were excluded from analyses of cattle foraging distributions because location records from rider data sheets were incomplete and reflected opportunistic rider movements rather than systematic searches for cattle. Therefore, telemetry-derived locations were spatially biased toward established riding routes and were not considered representative of cattle forage selection. However, future analyses will use telemetry data to evaluate whether access to cattle telemetry reduced rider response times to cattle groups and increased the duration of time a rider was present near livestock relative to riders without telemetry.

2. Cattle vigilance data was collected by our game cameras and also organized by unique camera deployment. Vigilance is the amount of time cattle spend moving or on the lookout for predators rather than eating, ruminating, or resting, all of which contribute to weight gain, reproductive success, and improved body scores (Laundré et al., 2001). We defined vigilance as head up above the ground. Non-vigilant behavior was defined as head at the ground (foraging/grazing - see Figure 3 for example photos). We were unable to use more fine-scale behavioral distinction as planned. We generated a behavior training dataset from our SpeciesNet cattle detections and annotated them manually to fit our definition criteria.

Unfortunately, our previously proposed method for classifying cattle vigilance behavior (LabGym - Hu et al., 2023) did not end up meeting our classification confidence threshold. As of December 2025, we are now building our own AI behavior classifier from scratch. This has slowed our process significantly, but once photos are coded, vigilance scores will be organized by unique camera deployment, and the proportion of total cows scored vigilant out of total cows detected will be analyzed.

By modeling both herd vigilance and herd landscape use/foraging behavior as a function of varied rider and predator activity, these data will allow us to answer the following research questions:

- Does rider activity influence the proximity of predators to cattle?

- Does rider activity influence vigilance in cattle?

- Does rider activity influence the quality of foraging areas used by cattle?

Cattle Biochemical Data

Although not a deliverable for this grant, we evaluated whether predator activity and varied range rider behavior influenced endocrine indicators of physiological stress in cattle. Endocrine measures, when interpreted alongside behavioral observations, provide a more comprehensive assessment of animal physiological condition than behavior alone (Boonstra et al., 2005; MacDougall-Shackleton et al., 2019). Cortisol reflects activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and is associated with energy expenditure and perceived risk (Gerlach, 2015). In contrast, thyroid hormones, regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (HPT), reflect metabolic activity, nutrient intake, and processes influencing body condition and reproduction (Gy et al., 2002). Interpretation of glucocorticoids can be challenging because cortisol responds to a variety of ecological and physiological stimuli not exclusively linked to stress (Gerlach, 2014), and prolonged stressors may producer muted glucocorticoid responses in some mammals (Caceres et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2015). However, sustained vigilance and reduced foraging may still manifest in lower thyroid concentrations even when cortisol responses are muted (Gy et al., 2002; Pryce et al., 2001). Jointly evaluating cortisol, thyroid hormones, and vigilance behavior allows a more robust assessment of predator-induced physiological effects than any single metric alone.

Sample Design

We collected tail hair samples because hair provides an integrated measure of endocrine activity over extended periods, and tail hair grows longer than body hard on cattle, reflecting cumulative rather than acute physiological responses. We sampled at least 30% of each participating herd to capture both intra- and inter-herd variation. Sampling occurred twice annually: in the spring immediately before cattle turnout onto grazing allotments, and in the fall following herd return at the end of the grazing season. The initial spring sample for each ranch served as a baseline for pre-grazing endocrine levels. To ensure fall samples reflected hormone accumulation during the grazing period only, tail hair was trimmed each subsequent spring (without analysis) to remove prior growth. Therefore, each herd contributed one baseline spring sample and one fall sample per ranch-year (1-3 years depending on participation). Tail hair samples (~5 cm) were trimmed using electric clippers and submitted to the Endocrinology Laboratory at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (Front Royal, Virginia) for hormone extraction and analysis. Hormone concentrations were quantified from hair and reported as ng/g hair sample.[RN4]

Hormone Extraction and Assay Procedures

Hair cortisol and thyroid extraction followed established protocols adapted from Meyer et al. (2014). Samples were washed in ethanol to remove external contaminants such as dirt, sweat, and sebum, then dried and ground into a fine powder to disrupt the keratin matrix and improve extraction efficiency. Approximately 0.10 ± 0.02g of powdered hair was incubated in 2 ml of 100% methanol for 24 hours under continuous agitation. Samples were then centrifuged for 5 minutes, the supernatant collected, evaporated under air, and reconstituted in Assay Buffer Concentrate X053 (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI) before storage at −20 °C until analysis.

Cortisol concentrations were quantified using an in-house enzyme immunoassay (EIA; R4866, Munro, University of California, Davis, CA; 1:85 [C.J. Munro, University of California, Davis]) validated in multiple wildlife studies (Young et al., 2004; Maly et al., 2018; Putman et al., 2019; Fazio et al., 2020). Samples were run in duplicates. Inter-assay variation was <15% and intra-assay variation was <10%. Assay sensitivity was 0.78 pg/ml. Serial dilutions of fecal extracts produced a displacement curve parallel to the standard curve, and recovery of added standards averaged 94% (y = 1.1691x -3.3064, R2 = 0.9943).

Triiodothyronine (T3) concentrations were quantified using a commercial T3 ELISA Kit (K056-H1, Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI). Samples were run in duplicates. Inter-assay variation was <20% and intra-assay variation was <10%. Assay sensitivity was 37.4 pg/ml. Serial dilution of fecal extracts yielded a displacement curve parallel to the standard curve, and recovery of added standards was 113% (Y= 1.0077x + 510.86, R2 = 0.9961).

Research Objective 1 - Models and Statistical Methods

Our objective was to identify whether varied range riding activity alters behavioral indicators of stress in cattle. Our research hypotheses were that as rider intensity, time spent within proximity of the herd, and time riding from dusk to dawn increased, we would also see a 1) decrease in seasonal herd vigilance and 2) cattle use of high availability foraging areas will increase.

Model 1a. - Herd Vigilance

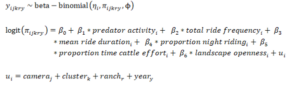

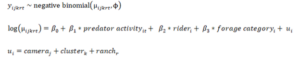

Vigilance data has not been analyzed due to the needed change in AI coding software. We plan to model herd vigilance as the number of vigilant cattle relative to the total number of cattle observed using a Bayesian beta-binomial generalized linear mixed model. Vigilance behavior in cattle (similar to wild ungulates) is facilitated socially, meaning vigilant behavior in one animal increases the likelihood of vigilance among nearby animals. This contagion violates the independence assumption inherent to binomial and Poisson distributions for count data. A beta binomial likelihood accommodates for within-group dependence, facilitating improved estimation and parameter certainty. Using the brms package (version 2.23, Bürkner, 2017), which implements Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling via Stan (Carpenter et al., 2017) via program R (version 4.5.2, R Core Team, 2026), we will model vigilance counts for unit i (ranch-year) as:

where yijkry is the number of vigilant cattle per game camera deployment, ni is the total number of cattle observed per unique game camera deployment, 𝝅iijkry is the probability of vigilance on the logit scale, and theta is the dispersion parameter for the binomial process. We modeled random intercepts for camera, ranch, cluster, and year to account for the hierarchical structure and repeated observations (normally distributed with a mean of zero and estimated variance). Our fixed effects, informed by our hypothesis, include:

- Predator activity (indexed as total number of wolf and/or grizzly bear photos per unique camera deployment),

- Rider frequency (indexed as the total number of rides per ranch-season,

- Mean ride duration (indexed as the averaged ride duration across all sampled rides per ranch-season,

- Mean proportion night riding (indexed as the proportion of each sampled ride taking place between dusk and dawn, averaged over all sampled rides per ranch-season,

- Mean proportion of cattle effort (indexed as the proportion of each sampled ride focused on cattle related activities (see definition for “cattle related” above) averaged over all sampled rides per ranch year, and

- Landscape openness (indexed as a percent per ranch year across all utilized pastures).

All continuous predictors will be standardized to improve coefficient interpretation and model convergence. Predictors will be evaluated for collinearity using Pearson's Correlation Tests and a threshold of |r| ≥ 0.7. We will specify weakly informative priors to regularize parameter estimates while allowing our data to inform our posterior distributions, and run sensitivity tests to ensure posterior estimates are not artificially driven by priors. Convergence will be assessed using the Gelman-Rubin diagnostic, with values less than 1.01 indicating adequate convergence (Gelman & Rubin, 1992; Vehtari et al., 2021). Effective sample size (ESS) and traceplots will be used to evaluate sampling efficiency and visually inspect chain mixing, and we will ensure sufficient exploration of the posterior distribution by the lack of divergent transitions. Model fit will be evaluated using posterior predictive checks to compare simulated datasets from the posterior predictive distribution to observed data (Gelman et al., 2013).

Model 1b. - Forage Selection

Because rider telemetry data were incomplete and spatially biased toward customary riding routes, cattle location information from rider datasheets were not considered representative of cattle forage selection and space use, and therefore not used for analyses. Instead, we used our systematically deployed game cameras spanning gradients of forage availability to quantify cattle space use and evaluate how predator and rider activity influence cattle selection. Range cattle, like wild ungulates, exhibit spatial aggregation driven by forage quality and social dynamics, so we used count data as a proxy for herd subgroup clustering behavior. We modeled cattle selection of camera clusters with varied forage availability as the daily count of cattle detected at each unique camera deployment, aggregated across all cameras in that cluster to better reflect spatial scales relevant to cattle grazing movement. These preliminary results used data from our 2024 grazing season (n=14 total operations).

Average forage biomass (kg/ha) per month was derived from the Rangeland Analysis Platform (RAP) across 30-m cells (Allred et al., 2021) and assigned to each unique camera deployment using a 30-m buffer. As a sensitivity test, variability across a 30m, 150-m, and 300-m buffer size was tested showing insignificant variation. Forage biomass values per camera were then averaged across all cameras in each camera cluster for a monthly cluster forage availability measurement. Cluster forage biomass values were then classified into low or high categories based on reference distributions calculated separately for each allotment within each month (summarized across RAP’s 16-day intervals). Cluster forage biomass values above the mean value per ranch-month were classified as high availability and cluster forage biomass values below the ranch-month mean were classified as low availability. This approach ensured camera cluster forage classifications were relative to local conditions (both spatial and temporal) rather than imposed uniformly across the study area. For example, a “low” camera group forage classification is interpreted as low relative to the allotment-wide seasonal production range within that monthly window, not relative to other camera clusters or operations. Daily cattle counts were derived from photographs on dates when at least one camera within a group was active. Days with no cattle detections were recorded as zero to preserve the observation process. To ensure accurate representation of sampling effort, we removed any dates a camera was considered inactive indicating malfunction or theft. Each camera’s last photo was used to determine the date a camera became inactive. 74.4% of cameras recorded photos within two days of being pulled from the field, suggesting minimal data loss due to inactive days.

We modeled cattle detections per camera-day as an index of cattle space use/intensity (total number of cattle detected per active camera, per day aggregated across all photos recorded that day). Because we could not identify individual cattle, detections may represent repeated observations of the same individuals/groups. Therefore, our response is an index of cattle activity/intensity of use, and not a measure of abundance. We fitted a Bayesian generalized linear mixed model with a negative binomial likelihood implemented in the brms package (version 2.23, Bürkner, 2017) in program R (version 4.5.2; R Core Team, 2026). Remote game camera count data are often overdispersed, and a negative binomial with log-link can accommodate overdispersion better than a Poisson distribution. We modeled cattle counts for unit i (ranch) as:

where yijkrt is the total number of cattle i detected at camera j from cluster k on day t on ranch r, and μijkrt is the expected cattle count. ϕ is the dispersion parameter.

To account for repeated measures and site-specific differences in baseline detection rates, we included a random intercept for unique camera deployment (j). We also included random intercepts for camera cluster and ranch to account for hierarchical structure and repeated observations across ranches and cameras (normally distributed with a mean of zero and estimated variance). Our fixed effects, informed by our hypothesis, include:

- Predator activity (indexed as the total number of wolf and/or grizzly bear photos per unique camera deployment),

- Rider (indexed as both 1) total rides per ranch-season, and 2) a binary representing whether or not the herd had a rider present that date (yes/no),

- Forage availability classification for each camera cluster (indexed as low or high).

We ran two sub-models - one with all 14 ranches using total ride frequency as our rider metric, and one with 11 of the ranches where rider activity by date could be analyzed (rider present that day or not). All continuous predictors were standardized to improve coefficient interpretation and model convergence. Predictors were evaluated for collinearity using Pearson's Correlation Tests and a threshold of |r| ≥ 0.7 with no high correlations detected. We ran four chains of 5,000 iterations each, with 2,500 warmup iterations per chain, yielding 10,000 post-warmup draws. No thinning was applied (thin = 1). We specified weakly informative priors to regularize parameter estimates while allowing our data to inform our posterior distributions and ran sensitivity tests to ensure posterior estimates were not artificially driven by priors (normal(0, 1) for fixed effects and random intercept standard deviations). Convergence was assessed by inspecting traceplots for adequate mixing and using the Gelman-Rubin diagnostic with R-hat values less than 1.01 indicating adequate convergence (Gelman & Rubin, 1992; Vehtari et al., 2021) and by inspecting effective sample size (Bulk_ESS and Tail_ESS).

Models 1civ. and 1cv. - Cortisol and Thyroid

Our preliminary analyses on hormone concentrations used only inferential tests and not fully specified multivariable models (see Results section).

Research Objective 2 - Qualitative Interview Methods

Conflict reduction tools are often created and evaluated without the direct involvement of ranchers. This can result in tools being researched at inappropriate temporal or spatial scales, or testing within a limited scope that does not account for the diverse, complex, and sometimes limiting relationships between an operation’s social, ecological, and economic dynamics (Naugle et al., 2020; Chambers et al., 2021; Hyde et al., 2022). In turn, this can result in tools or solutions that are not feasible to deploy or maintain, are cost-prohibitive, or simply ineffective in certain contexts (Chambers et al., 2021). The coproduction of our research questions and methods has ensured our approach to quantitative analyses is relevant to operational processes. By also collecting qualitative data, we helped ensure contextual understanding of our quantitative findings from our project partners, utilizing range riding regularly.

Recruitment

We conducted semistructured interviews (Interview Questions CIG) with producers and range riders who participated in our research using criterion-based purposive sampling (Campbell et al., 2020). We interviewed 20 participants; nine interviewees were from Montana residents, seven from Washington, two from Arizona, and one from both Oregon and New Mexico. Eight interviewees identified primarily as a producer, seven as a range rider, and five as occupying both identities/roles (i.e., livestock producers who ride their own herds regularly). All operations have active wolf populations and operations in Montana, and one operation in Washington, also have active grizzly bear populations. All interviews were conducted with participants’ informed consent and adhered to the ethical standards of the Utah State University Institutional Review Board (protocol #12545).

Interview Guide

We designed a semi-structured interview guide to elicit rancher and range rider perspectives on range riding as a management tool. Interview questions prompted participants to reflect on why they chose to participate in range riding, whether they perceived range riders as proficient in various conflict mitigation strategies, how to deploy riders effectively, historical and present predator conflict context, perspectives on range rider programs, and perspectives on communication and coordination within range rider efforts and/or range rider programs. Interviews were conducted in person between April 2021 and December 2024 and were audio recorded for transcription and analysis. Consistent with semi-structured interviewing practice, participants were encouraged to lead conversations toward topics they felt most relevant to their own experience (Tisdell & Merriam , 2025).

Analysis

We conducted a hybrid deductive-inductive thematic content analysis, a method used to systematically code qualitative data by identifying recurring patterns or themes relevant to research objectives (Saldaña, 2016; Clarke & Braun, 2017). Deductive analysis applies existing theoretical concepts or research to guide the coding process, whereas inductive analysis allows additional themes, patterns, and concepts to emerge directly from the data through repeated transcript review (Clarke & Braun, 2017; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Our thematic content analysis had three phases. In phase one, our team reviewed the Gonzalez et al. codebook (2024) developed for an evaluation of state-funded range rider programs in Washington State to understand definitions of categories and themes. Prior to formal coding, we developed an initial codebook by adapting the Gonzalez et al. (2024) codebook to reflect the present dataset and research objectives. Drawing on researcher immersion and contextual familiarity with the system, we retained applicable codes and added new codes to capture themes not included in the Gonzalez et al. (2024) framework (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006; Braun & Clarke, 2021). In phase two of analysis, two researchers used the initial codebook to independently code four transcripts representative of the varying stakeholders that participated in interviews. Through this inductive process, researchers finalized the codebook by identifying new codes, adjusting codes, and reconciling discrepancies in coding through consensus. In the third phase of analysis, coders used the final codebook to complete coding all 20 interviews and reviewed one another's work to meet consensus. Interviews were transcribed using Otter.ai software (Otter.ai, Inc.) and coded using Dedoose software (Version 10.34; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC).

Over time, as operations, participating producers, predator populations, and extenuating circumstances have evolved over the last four years, so have our research objectives to accommodate. To note, the primary research objectives to help achieve our project’s consistent goals are:

- Evaluate the effectiveness of different intensities and styles of riding at reducing behavioral and chemical indicators of stress in grazing livestock.

- Through interviews with ranchers, provide the context and detail necessary to understand decision making around range riding as it relates to operational management and protocols, ecosystem resiliency, and economic sustainability.

Other project objectives are primarily concerned with education and outreach, so they are described in detail in the educational section below. However, all the results and information we learned from reaching our research objectives were applied to the educational objectives. Through objective 3, we worked to ensure the information was accurate and readily available to incorporate into objectives 2 and 4 using an iterative process. As we gained information from objective 1, we tried to incorporate it into the outreach materials, disseminate it at workshops, and discuss it at rancher-to-rancher exchanges. We used feedback from ranchers and other stakeholders about the clarity of information, the relevancy of these findings to their practices, and what other information was needed.

Over time, as operations, participating producers, predator populations, and extenuating circumstances have evolved over the last four years, so have our research objectives to accommodate. To note, the primary research objectives to help achieve our project’s consistent goals are:

- Evaluate the effectiveness of different intensities and styles of riding at reducing behavioral and chemical indicators of stress in grazing livestock.

- Through interviews with ranchers, provide the context and detail necessary to understand decision making around range riding as it relates to operational management and protocols, ecosystem resiliency, and economic sustainability.

Results Objective 1: Research Findings

Research Objective 1a. - Cattle Vigilance Model

Results forthcoming (see above).

Research Objective 1b. - Cattle Forage Selection Model

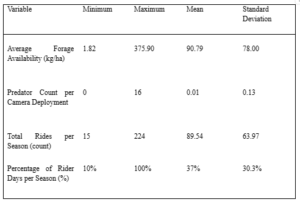

Our remote game cameras accumulated 47,054 camera days for the 2024 grazing season. Of the 95 unique clusters across 14 different ranches, 34% were considered high forage availability, and 66% were considered low. For the maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation values for cluster mean forage biomass, total predators, total rides, and proportion of season days with a rider, see Table 1.

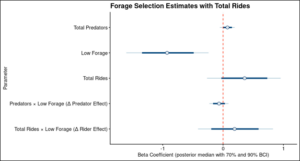

Model 1 - Total Rides

To model cattle forage selection based on predator activity and total rider frequency (rides per ranch-season), our model included 47,054 observations across 886 unique camera deployments, 95 unique clusters, and 14 ranches. All parameters demonstrated convergence (R^ = 1.00) with an adequate effective sample size indicating stable posterior estimates (Bulk_ESS > 1,500, Tail_ESS > 2,000). No divergent transitions were observed. Our shape parameter was estimated at 0.14 (95% Bayesian Credible Interval (BCI): 0.13, 0.15), indicating significant overdispersion and supporting our use of a negative binomial distribution. Posterior predictive checks indicated that the model adequately reproduced the distribution of observed counts.

Random Effects Model 1

Substantial variation in cattle counts occurred at the camera level (σ = 2.84, 95% BCI: 2.55, 3.18), with moderate variability among clusters (σ = 1.67, 95% BCI: 1.25,2.13) and ranches (σ = 0.60, 95% BCI: 0.04, 1.40).

Fixed Effects Model 1

Cattle counts were significantly lower in low forage availability clusters relative to high availability (β = -0.92, 95% BCI: -1.75, -0.11). Expected counts of cattle were approximately 60% lower in low forage areas. Neither predator activity (β = 0.07, 95% BCI: -0.08, 0.22) nor rider activity (β = 0.35, 95% BCI: -0.38 to 1.09) were strongly associated with cattle counts, although increased predator activity was positively associated with cattle counts in this model. Interaction terms between predator activity and forage category (β = -0.07, 95% BCI: -0.26, 0.12) and between rider frequency and forage category (β = 0.20, 95% BCI: -0.53, 0.95) were small and not meaningful, providing little evidence that predators or riders altered forage selection patterns. (Figure 4).

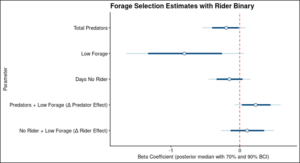

Model 2 - Daily Rider Presence

To model cattle forage selection based on predator activity and whether or not a rider was active each day (rider binary), our model included 35,670 observations across 606 unique camera deployments, 66 unique clusters, and 11 ranches. All parameters demonstrated convergence (R^ = 1.00) with an adequate effective sample size indicating stable posterior estimates (Bulk_ESS > 1,500, Tail_ESS > 2,000). No divergent transitions were observed. Our shape parameter was estimated at 0.13 (95% Credible Interval (BCI): 0.11, 0.14), indicating significant overdispersion and supporting our use of a negative binomial distribution. Posterior predictive checks indicated that the model adequately reproduced the distribution of observed counts.

Random Effects Model 2

Substantial variation in cattle counts occurred at the camera level (σ = 3.06, 95% BCI: 2.67, 3.49), with moderate variability among clusters (σ = 1.32, 95% BCI: 0.73, 1.95) and ranches (σ = 0.99, 95% BCI: 0.17, 1.86).

Fixed Effects Model 2

Cattle counts were significantly lower in low availability forage clusters relative to high availability forage clusters, but the effect was only moderately meaningful (β = -0.80, 95% BCI: -1.80, 0.23). Expected counts of cattle were approximately 55% lower in low forage areas. Increased predator counts had a moderately meaningful negative effect on cattle counts (β = -0.21, 95% BCI: -0.63, 0.13). A one SD increase in predator count (0.13) was associated with an expected 19% decrease in cattle counts. Days without a rider were associated with slightly lower cattle counts overall, but the effect was not meaningful (β = −0.15, 95% BCI: −0.52, 0.21). Our interaction term between forage availability and rider presence was not meaningful (β = 0.11, 95% BCI: -0.35, 0.57), suggesting limited evidence that rider presence impacted forage selection in cattle. However, our forage availability and predator activity interaction was moderately meaningful (β = 0.24, 95% BCI: -0.14, 0.68). A one SD increase in predator count was associated with an expected 24% increase in cattle use of low availability forage areas, suggesting predator activity may influence cattle to select for lower quality foraging areas (Figure 5).

Research Objective 1civ. and 1cv. - Exploratory Analyses of Cortisol and Thyroid

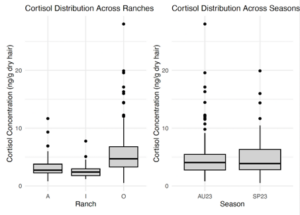

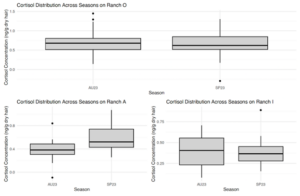

In 2022, we collected n = 319 cattle hair samples, n = 1090 in 2023, and n = 747 in 2024. Of these samples, 2152 were viable for cortisol analysis, and 719 were viable for thyroid. Although our cattle vigilance behavioral data is not yet ready to compare with our cortisol, thyroid and body condition score results, we conducted a preliminary analysis of tail hair samples collected during the 2023 grazing season (spring and fall) from three geographically and operationally similar ranches: Ranch O (n = 162), Ranch A (n = 27), and Ranch I (n = 33). Ranches were selected to minimize environmental and management variation that may independently influence endocrine markers (Heimbürge et al., 2019; Moya et al., 2013; Bristow & Holmes, 2007). We evaluated differences in cortisol and thyroid hormone concentrations across 1) season (spring vs. fall) and 2) ranch.

Cortisol

A two-way ANOVA (Fisher, 1925) revealed a significant main effect of ranch on cortisol concentrations (p < 0.001) and a significant ranch × season interaction (p = 0.02), but no overall main effect of season (p = 0.94). Ranch explained approximately 20% of the variance in cortisol concentrations, whereas season explained less than 1% (Figure 6).

Post hoc Tukey’s HSD tests (Tukey, 1949) indicated no significant difference between Ranch I and Ranch A (p = 0.27). However, Ranch O exhibited significantly higher cortisol concentrations than both Ranch A (p < 0.001) and Ranch I (p < 0.001). Season remained non-significant in post hoc comparisons (p = 0.95). The significant interaction reflected consistently higher cortisol concentrations at Ranch O relative to Ranch I in both spring and fall (p < 0.001 for both seasons), and higher concentrations relative to Ranch A in autumn only (p < 0.001).

Paired t-tests (Student, 1908) were conducted to assess seasonal differences within ranches (Figure 7). Ranch O showed no significant seasonal difference (p = 0.23; mean difference = −0.04 ng/ml). Ranch A exhibited a significant seasonal increase (p < 0.01; mean difference = 0.25 ng/ml). Ranch I showed no seasonal difference (p = 0.95; mean difference = 0.00 ng/ml).

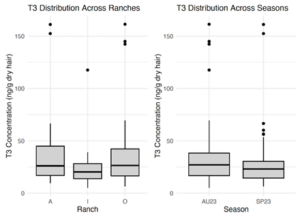

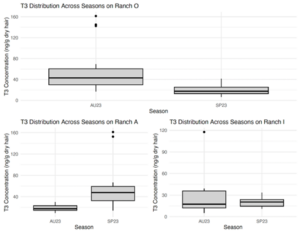

Thyroid Hormone (T3)

Because thyroid data were non-normally distributed, we used a Kruskal–Wallis test (Kruskal & Wallis, 1952). Ranch had a significant effect on thyroid concentrations (p = 0.05), whereas season did not (p = 0.34; Figure 8). Dunn’s post hoc tests (Dunn, 1964) indicated significant differences between Ranch A and Ranch I (p = 0.02), and between Ranch O and Ranch I (p = 0.02), but no difference between Ranch O and Ranch A (p = 0.43).

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (Wilcoxon, 1945) were used to assess seasonal differences within ranches (Figure 9). Ranch O (p < 0.001, V = 13) and Ranch A (p < 0.001, V = 102) exhibited significant seasonal differences in thyroid concentrations, whereas Ranch I did not (p = 0.78, V = 70).

Research Objective 2 - Qualitative Interviews

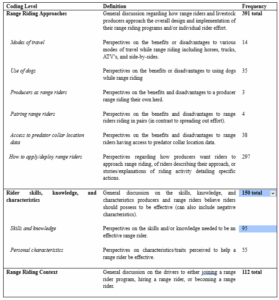

Across our 20 participants, our analysis resulted in three categories of perceptions: 1) range riding approaches (6 themes, 10 unique codes), 2) rider skills, knowledge, and characteristics (2 themes, 2 unique codes), and 3) range riding context (1 theme, 1 unique code). See Table 2 for each theme and code, along with their definitions, organized within their corresponding category.

We coded specific perceptions across our three categories a total of 653 times (Table 2). Our most frequently coded category was range riding approaches (n=391), followed by range riding context (n=321), and rider skills, knowledge, and characteristics (n=150). Every participant shared at least one perspective on all six categories. The following results explore the top three themes within each category.

Range Riding Approaches

Participants most frequently discussed how to apply/deploy range riders (Table 2) with participants describing perspectives on optimal riding frequency, timing, responsibilities, communication expectations, and overall effectiveness.

Rider Frequency

Most participants shared that frequent riding - ideally near daily - was important for effectiveness. However, the right frequency was considered context-dependent, influenced by allotment size, terrain, accessibility, and current predator conflict. Interviewees emphasized the importance of the rider learning the landscape, wildlife, and livestock patterns in order to effectively detect shifts that may signal emerging conflict, and adapt frequency accordingly. Several participants mentioned that on large rugged allotments, complete coverage in a single day was often unrealistic; thus, how often a rider rides was generally considered more important than for how long they ride.

When to Ride

Participants expressed mixed views on night riding. Several participants acknowledged that riding when predators were most active (e.g., dawn to dusk) may improve riding’s effectiveness, but felt this posed more safety risks - particularly with the risks associated with riding horses in the dark, not being able to see well enough to be effective, and the potential threat of encountering a grizzly bear at night outweighing potential benefits. One producer described their experience trying to range ride at night:

“Total waste of money in my own opinion, I think it razzled the cows more than we helped that night, so I never went out again. And as far as taking a horse out…it's not even logical.”

Other participants felt night riding provided a unique opportunity to detect abnormal behavior in cattle that would normally be bedded at that time. Camping in the herd, rather than actively riding, was frequently mentioned as a way to reduce response and commute times.

What Riders Should Focus on While Riding

Participants shared frequently that riders should prioritize monitoring cattle and locating as many animals as possible. Activities like checking cows for illness, injury, and stress were mentioned as essential, and having knowledge in livestock was seen as necessary to do those tasks well:

“You have to understand cattle...people that don't understand and don't know how to read cattle and cannot comprehend what is going on…make it worse.”

Some participants shared that operational or “cowboy” tasks such as fixing fence, putting out salt, or doctoring injured or sick animals were integral to effective range riding, while others viewed these tasks as unnecessary to a rider’s core goals:

“...that's why I say all riders should be cowboys. Because what the hell good does it do to have this guy just out there riding around and not see that the fence is down? It all goes together. And besides that, if he doesn't see that the fence is down, maybe there's seven cows over here that he doesn't even know…if it's a cowboy, he's going to see that…He's going to say, ‘Oh, I must have some cows over here…I better go see where they are and put them back wherever they belong’.”

Participants also shared that riders should monitor predator activity by tracking their sign (e.g., tracks, scats, behavior), detecting depredations, managing game cameras, and hazing predators when necessary.However, some participants believed that excessive time spent away from the herd could be detrimental as changes in cattle behavior are often the earliest indicator or predator conflict.

Participants frequently mentioned using creative ways to "mix up" their rider activities and patrol routes to take advantage of predator fear of humans. One rider noted that wolves may become familiar with rider presence and scents over time, thus it is essential riders change their approaches and behaviors regularly to ensure they stay “...something (for the wolves) to worry about.” Participants also mentioned that riders should be adaptable, observant, and curious:

“...I don't think like, trotting through pasture and covering every patch is going to be quite as informative as…taking your time and…just observing what's around you."

Perceptions on Rider Effectiveness:

Participants described varied definitions of range riding effectiveness. Most participants questioned whether riders can reduce predator depredation, particularly from highly motivated predators:

“They (the riders) are not going to have any effect if that wolf hits or if that bear hits cattle ever…We cannot be that omnipotent, or whatever you want to say…that's giving us way too much credit. Yeah, we're not going to change their habits.”

Others felt their ability to reduce depredation was apparent:

“There's no doubt in my mind that it works to a point…I mean, anytime you got eyes and ears out there, you're looking at something."

“...they had a lot of losses, and as soon as we started riding, they didn't have an issue again last year.”

Several respondents suggested that predator hunting and trapping seasons may improve rider effectiveness by reinforcing predator fear of humans:

“Certainly the fact that we shoot our wolves here and trap our wolves, I think trapping plays a big part, and maybe a lot more than people realize...”

Many participants emphasized that direct loss/depredation reduction may be difficult to quantify, and may not fully capture the value of a range rider:

“No, yeah, I don't feel like we prevent depredations at all. I feel like we very effectively, though, keep ranchers in a (calm) mental state…and keep them on the landscape…at the end of the day…what is like, the ultimate goal? Is it preventing depredations or is it keeping ranchers?...I feel like we are very effective at supporting the ranchers, making them feel like they're not alone…reducing their anxiety. They can sleep better at night.”

“And my measure of effectiveness is if the landowners are happy with it, if they thought it was worth it, then it was effective. It doesn't matter if every cow died, if they (the rancher) thought that he (the rider) did something up there that was helpful, then it was effective.”

“Maybe I would have had 10 calves killed, 14 calves killed in 2015 instead of 5, because the range riders did a good job.”

Interviewees also highlighted the importance of communication and collaboration between riders, producers, and wildlife agencies as part of their effectiveness, particularly concerning timely lethal removal in cases of chronic depredation. Riders were viewed as critical information gatherers that support agency decision making, but riders are not solely responsible for resolving persistent conflict. Most preferred daily communication, with one producer noting:

“I'd rather have too much communication than not enough.”

Participants discussed whether or not riders are effective at displacing conflict spatially. Most felt any spatial displacement was localized and temporary, but that information sharing across operations was a significant benefit.

Opinions varied regarding whether riders meaningfully reduce predator-induced stress in livestock that leads to indirect losses (e.g., reduced pregnancy and return rates, increased illness rates, decreased weaning weights). Some participants believed livestock stress was at least alleviated while riders were present with the herd.

Participants acknowledged that learning the livestock and the landscape takes time, and thus rider turnover was one of the largest hindrances to long term effectiveness:

“The golden ticket for a range rider is finding somebody who can stay for a long amount of time. It's hard to learn country. It's hard to learn the different herds and their different behaviors. It's time consuming as a producer to train these people and teach these people.”

Access to Predator Collar Location Data

Access to predator collar location data was the second most coded perception (Table 2), where participants described the potential benefits, limitations, and challenges obtaining data from agencies. GPS collars were considered useful for identifying broader predator movement patterns, however, data delays often limited utility for rapid response. Alternatively, VHF collars were viewed as more useful for real-time response, though limitations included terrain constraints.

“And it (predator location information) gave us detailed information where they were at…And it was wonderful, because if they weren't in the area, then I felt like I could go about my business. If they were in the area, and then I'd go out, check and see what was going on. So that was really helpful.”

“I can't track the ones I can't find, right? I mean, being able to zero in and find specific wolves (VHF) is more beneficial to me…I don't need to know where the wolves were two weeks ago. I need to know where they were two hours ago.”

Participants described barriers to accessing timely collar data from wildlife agencies (primarily due to poaching concerns), and emphasized the role location sharing by agency staff with producers and riders played in building trust and partnership:

“I think from a long term relationship…I think it would be more functional for the department to monitor collar data and be transparent with those things…I think it's a great way for landowners and agency folks to kind of keep breaking down some of those barriers that exist”.

Others argued that skilled riders should not need collar data to be effective:

“...if your rider’s out there, and he's listening, looking and reading the signs on the ground. He knows whether they (the wolves) are there or not there.”

The drawbacks to using dogs (cons dogs) was the third most cited perception (Table 2). While dogs may provide protection from grizzly bears, participants raised concerns about dogs attracting bears and causing potential human mortality, and increasing stress in livestock, particularly in areas with elevated wolf activity:

“When I have wolves in my cattle, I cannot use my herd dogs at all…I have to go in by myself. The cattle are so scared and stressed out that they run everything into the dirt, even horses.”

Range Riding Context

This category had one specific theme: Why range riding and/or main goals for having a rider (Table 2). Common primary goals for employing a rider included livestock monitoring, minimizing depredation, providing presence, improving response times, early detection of potential depredations, information gathering, and protecting a producer’s economic investment:

“I feel better having (rider) and his feedback, and his presence on the landscape, helps me feel like my cattle are having a better opportunity at success.”

“So you know what's going on. So if you do have a depredation you can actually find it, otherwise you're going to have 20 of them before you ever know you had one. That's why I think they're important.”

“Ranching is labor intensive, and we already have too much work to do, and having to babysit predators is just one more thing that we have to try to fit in. And if we're trying to do a good job keeping predators at bay and keeping our livestock alive, then we don't have time to do the rest of our work. And because we didn't ask for these predators to be here, somebody else needs to manage them so that we can manage our livestock.”

One rider stated:

“I think it's time to bring range riders back. They're necessary again. And I see my job as an insurance policy…”

Perceived Additional Benefits

Perceptions of range riding effectiveness were often linked to perceived additional benefits that motivate a producer to deploy a rider. Additional benefits included wildfire detection, operational support through holistic risk management, relationship building, and maintaining the viability of livestock production:

“...ultimately, you're helping everybody, you know? By me being out trying to keep the depredations down, it’s helping the environmental groups with their goal of not killing (predators). Helping the rancher with keeping the cows safe.”

“The benefit for me personally, would be coming out with 100% success rate of our calves, but (in addition) you're building relationships…that's a really important part of their job is building that relationship piece.”

“And I think if you want to keep open space and not see things turn into housing developments you need to keep producers on the landscape. And part of keeping producers on the landscape is keeping their operations viable. And to keep them viable, you can't be having 40% open cows, you can't be losing 20% of your herd to depredations… There's a reason that the elk spend their time on my ground. There's a reason that the grizzly bears spend their time on my ground.”

Rider Skills, Knowledge, and Characteristics

Similar to our findings under the how to apply/deploy range riders theme, stockmanship, track and sign identification, and communication/documentation were seen as essential skills:

“They have to be able to read a cow. Know if a cow is stressed out, know, if a cow is hurting, know if a cow's about to die.”

“...being able to track - know whether you're tracking wolf tracks, or whether you're tracking cougar tracks or cow tracks, you know. Being able to take in and decipher the difference on a cow track, or yearling track, or bull track, and figure out…what's going on.”

“If you don't communicate, we're gonna be losing cattle and they're gonna be dying, and then it's bringing in more predators, because we have dead cattle for no reason. So (the rider) has to be able to communicate to you (the producer), that is a big asset.”

Participants described additional skills that contribute to a rider’s effectiveness including backcountry competence, landscape literacy, observational awareness and knowing what’s abnormal or unusual, and game camera proficiency. While participants noted many skills can be learned, structured training opportunities were requested.

Personal characteristics was the second most coded perception (Table 2), where participants described trustworthiness, integrity, patience, work ethic, and eagerness to learn. Trust was noted by all participants as extremely important:

“If somebody doesn't know, well then don't bullshit me. Just say ‘I don't know’.”

“I think the trust is huge in that aspect to where they (the producers) trust the fact that they can call you (the rider), they know that you're going to be in there when you say you're going to be in there, and if they ask you to do something, you're going to do it. You know, there's been times for all of us (riders) that we have dropped what we're doing and go if we can. And I think that is a big deal to them (the producers)...there's days you drive out of there that you are just exhausted, you know…You've got to have a lot of go, really.”

“(Range riding) is like being an airplane pilot, hour upon hour of extreme boredom with brief intermissions of sheer terror…You got to be able to stand being alone. Be comfortable with yourself. Be confident with yourself .”

Teamwork, humility, and professionalism (particularly considering the contentious nature of predator-livestock conflict) were considered more important than any one technical skill.

Citations:

See citations at insert below.

Research outcomes

Research Objective 1a - Discussion and Recommendations Cattle Vigilance

Discussion and implications for sustainable agriculture forthcoming (see above)

Research Objective 1B - Discussion and Recommendations Forage Selection

Discussion

Our research objectives were to test whether cattle were selecting for high availability forage areas across sites with active game cameras and whether rider and predator activity impacted that selection. Our first model evaluated rider effect as total rides per ranch across all ranches, and our second model evaluated rider presence each day of the season (rider vs. no rider) on ranches where that scale of data was available.

The majority of variation in our models was attributed to unique camera deployment. This suggests substantial camera-to-camera differences in cattle counts that may reflect unmeasured site characteristics. In addition to forage availability and quality, cattle selection preference can also be motivated by preferred plant species, distance to water and salt/mineral, herding pressure, and slope/terrain ruggedness (Bailey et al., 2005; McDonald et al., 2019; Ashworth et al., 2024). While all cameras were set in locations within a ≤ 30% slope (ruggedness factor) and ≤ 1 mile distance to water, unique plant species and nutritional content was not evaluated and may have influenced camera cluster selection (Bailey et al., 2005; McDonald et al., 2019; Ashworth et al., 2024). Explicitly measuring heterogeneous camera location microhabitat variables (e.g. water tank or salt lick, visibility, forage quality/nutritional content, etc.) could clarify whether rider and predator activity interact with local environmental conditions at each camera site (Acciaro et al., 2022).

Both models found an effect of cattle selecting for high availability forage areas (although the effect in the second model was only moderately meaningful). Our findings are consistent with a substantial body of literature demonstrating that grazing cattle preferentially select areas of higher forage availability and quality (Bailey et al., 2005; Teague & Barnes, 2017; McDonald et al., 2019).