Progress report for SW23-956

Project Information

Limited water availability is a major issue in the western US. Leap et al. (2017) demonstrated profitable dry farmed tomato production in coastal California, and suggested that dry farmed tomatoes have improved flavor. The WSARE project, “Production and Marketing of Dry Farmed Tomatoes in Oregon” has demonstrated that dry farm tomato production is possible in the Willamette Valley using blossom end rot (BER) resistant varieties and grafting. However, many BER resistant varieties and grafted tomatoes were rated lower than ungrafted BER susceptible tomatoes like 'Early Girl' in overall preference during sensory evaluations.

Farmers want to grow flavorful tomatoes with low rates of BER. This project will create a “BER Toolkit” for farmers. All of these tools are based on Saure’s hypothesis that BER is the result of a sequence of luxurious growth followed by severe stress (Saure, 2014). We will test the effectiveness of the following "tools":

- Sheltering

- Soil amendments

- Decreased in-row spacing

- Deficit-irrigating transplants prior to planting

The toolkit will be disseminated to farmers through field days, publications, and videos made available on the Dry Farm Collaborative Youtube page. Farmers will understand all of the benefits and drawbacks of each “tool” and will be able to test a suite of them. A diversity of vegetable producers will be able to apply the principles of the BER toolkit to their farms whether irrigated or dry farmed.

Determining how to successfully dry farm ‘Early Girl’ tomatoes in the Willamette Valley will open up a high value market while reducing water use and increasing in-stream flows. It will eliminate the need for costly irrigation systems, increase profitability, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It will allow farmers on lands with no or limited irrigation rights to grow profitable crops with little to no risk, thereby increasing profitability and quality of life.

- Test and demonstrate a suite of "tools" for mitigating blossom end rot (BER) in dry farmed tomato production, all based on the Saure Hypothesis that BER is caused by a sequence of early season luxurious growth followed by severe stress.

- Tool 1: Sheltering by intercropping with dry farmed corn to reduce drought stress.

- Tool 2: Reducing soil amendment applications to reduce early season luxurious growth.

- Tool 3: Decreasing in-row plant spacing to reduce early season luxurious growth.

- Tool 4: Pre-stressing seedlings during nursery production to produce transplants with "Drought Stress Memory."

- Determine effects of tools on other measures of yield, fruit quality, wind run, cost of production, and plant health.

- Determine the interactive effects between the different tools.

- Demonstrate the effectiveness of the BER toolkit when implemented on farms.

- Educate farmers and agricultural professionals to different theories of the cause of BER in tomatoes.

- Educate farmers and agricultural professionals to the components of the BER toolkit (including grafting), how they effect crop production, and how they interact.

- Promote dry farmed tomatoes and educate the consumers, retailers, wholesalers, and other marketers to the value of dry farmed tomatoes, including environmental benefits and culinary value.

Cooperators

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

Year 1 (2023):

The tools in the BER toolkit were selected because they have been shown to reduce BER incidence in trials conducted from 2019-2022. The tools were based on the hypothesis presented by Saure (2014, 2001). Saure hypothesized that BER was the result of a sequence of a) rapid growth that predisposes fruit to BER followed by b) severe stress that results in cell death at the fruit’s blossom end (in the case of dry farming this would be drought stress). Therefore, the tools aim to either reduce drought stress or prevent rapid early season growth. The treatments are:

- Reducing drought stress by sheltering the crop from the wind – Rows of corn were planted to the north of plots to reduce wind run through the tomato crop. Corn patches were planted with 7 rows (2.5 ft between rows) that were 18 ft long (1 ft in-row spacing).

- Reducing rapid early season growth by limiting soil amendment application – this included a reduced amendment treatment (50 lbs of N per acre) and a no amendment treatment.

- Reducing rapid early season growth by decreasing in-row spacing and increasing between row spacing – We reduced the in-row spacing from 2’ 6” to 1’ 8” and the between-row spacing increased from 6’ 0” to 9’ 0”.

- Trellising – We trellised plants using a basket weave. We hypothesized that trellising would increase BER incidence and drought stress by elevating the crop and exposing it to the wind.

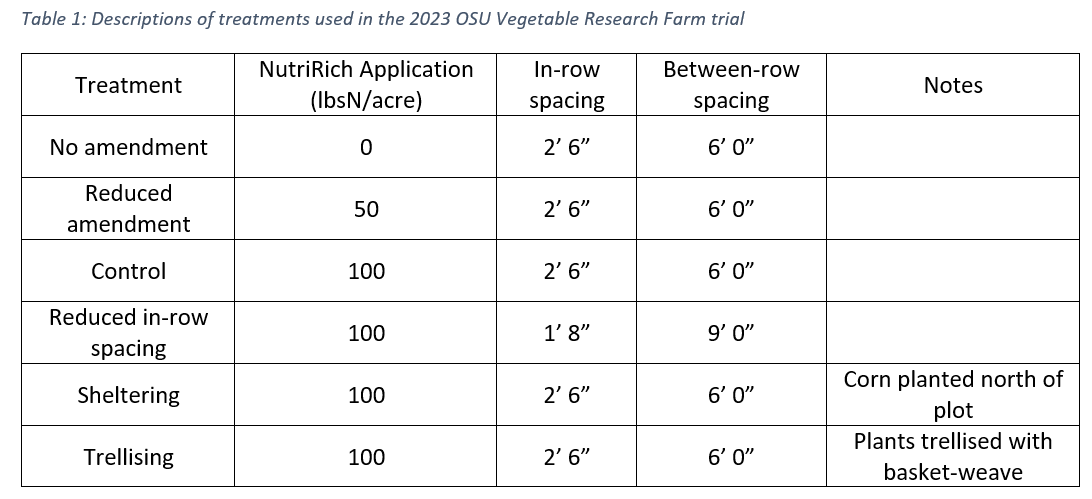

To test the effects of the treatments, two trials were conducted. The first was at the Oregon State University Vegetable Research Farm (VRF), and tested five treatments (sheltering, reduced amendment, no amendment, in-row spacing, and trellising) against a control. The treatments are detailed in Table 1.

The second set of trials were conducted on commercial farms throughout the mid-Willamette Valley. These trials tested the effect of fertilizer application on diverse sites to determine an optimum application. These treatments were the same as the no amendment, reduced amendment, and control treatments from the VRF trial. Each of the five farms had one replication of these three treatments.

Data collected included plot yield, fruit count, average fruit weight, incidence of BER, incidence of necrotic BER, incidence of yellow shoulder, incidence of sunscald, predawn leaf water potential, fruit soluble solids concentration, fruit titratable acidity, soil nutrients and pH, soil available water holding capacity, air temperature, air relative humidity, air vapor pressure deficit, and wind run.

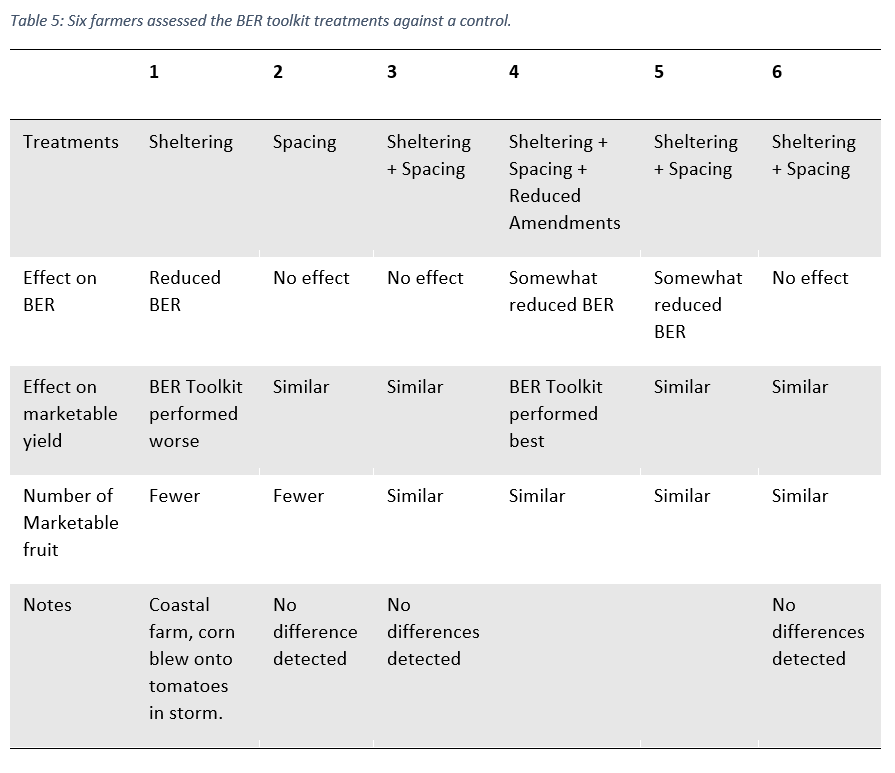

Additionally, six farmers independently trialed the BER toolkit. For these trials the farmers selected the tools that they wanted to trial against a control. They recorded their observations in a survey that we provided.

Year 2 (2024):

For year 2 of the project, we tested the interactions between three of the treatments (sheltering, fertilizer, and plant spacing). We originally intended to do this work at the VRF, however, there was very little BER in the 2023 VRF trial, so we instead planted a single replication of the trial per farm at six different farms. We were also able to conduct trials of pre-drought stressed seedlings at five different farms.

To test the interactions between the different treatments, trials were planted with a split-plot design. The main plots were either sheltered (with a shelter crop chosen by the farmer) or unsheltered (i.e. control). Within each main plot were four subplots planted in a 2×2 factorial with density treatments (high density and low density) and fertility treatments (high fertility and low fertility) The low density plots were planted at 7' × 36" and the high density plots were planted at 7' × 18". The high fertility plots received composted chicken manure (4-3-2) at a rate of 150 lbs/acre N and the low fertility plots received 75 lbs/acre N. See figure 1 for a map of one of the trials.

Figure 1: This is a map of the BER toolkit trial at Lewis Brown Farm. The top right corner is the Oaxacan Green corn patch. The bottom half is the BER toolkit trial, with four plots adjacent to the corn (sheltered) and four plots adjacent to the pre-drought stressed seedling trial (control). Each of the BER toolkit plots was made up of eight data plants (small box within each plot) and either 16 (if low density) or 24 (if high density) border plants. In the top left is the pre-drought stressed seedling trial, with six plots, each with five plants. There were three different stress treatments and two replications of each treatment in a CRD design.

Among the farmers, one chose 'Oaxacan Green' corn (farm 2), one chose sorghum (farm 3), one chose sunflowers (branching, farm 4), and one chose broomcorn (farm 7). Additionally the trial at VRF and Lewis Brown Farm (LB) shelters were planted with 'Oaxacan Green' corn. Shelters were planted with 12 rows (with 2.5 ft between rows) and were 75 ft long (with a 1 ft in-row spacing).

To test the effect of pre-drought stressing the seedlings on tomato yield and fruit quality, tomato seedlings were up-potted into 30 trays and then each tray was assigned a treatment of either control, reduced irrigation, or single drought. Control trays were irrigated when their weight fell below 90% of their weight at field capacity (this was 80% total moisture at field capacity). The reduced-irrigation trays were irrigated when their weight fell below 50% of their weight at field capacity (this was 20% of total moisture at field capacity). See figure 2 for a comparison at watering time. Single-drought trays received moisture similar to the control, but then water was cut off 3-4 days before planting. Irrigation treatments were applied from 30 April until planting using subirrigation. Trials were planted at five farms, with six plots at each farm (two replications), planted in a CRD. Each tray was used to plant a single five-plant plot (30 plots total) and the rest of the plants from each tray were used in the border.

Figure 2: Reduced-irrigation tray (left) and control tray (right) prior to irrigation.

Plots were kept free of weeds for the growing season.

Data collected included plot yield, fruit count, average fruit weight, incidence of BER, incidence of necrotic BER, incidence of yellow shoulder, incidence of sunscald, predawn leaf water potential, root length density (2' and 3'), fruit soluble solids concentration, fruit titratable acidity, soil nutrients and pH, soil available water holding capacity, air temperature, air relative humidity, air vapor pressure deficit, and wind run.

Year 1 Results (2023):

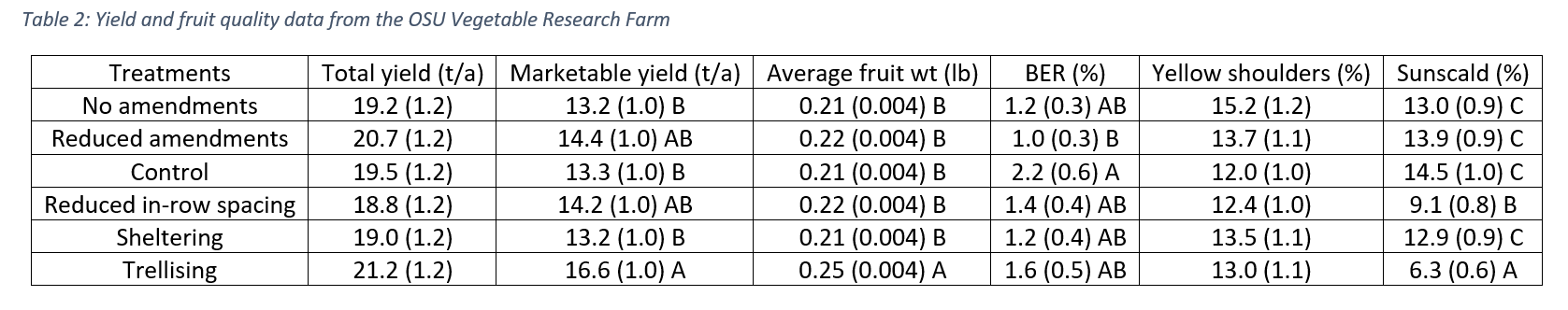

Table 2 shows the effect of the different treatments on yield and fruit quality for dry-farmed tomato grown at the OSU Vegetable Research Farm. Treatments did not differ in mean total yield. Treatments did differ in mean marketable yield, with the trellised treatments having higher mean marketable yields than the no amendment treatment, the control, and the sheltered treatment. Trellising also resulted in larger fruit than any other treatment. Treatment impacted mean BER incidence, with the reduced amendment treatment having lower mean BER incidence than the control treatment. It should be noted that there was incredibly low BER incidence in the OSU Vegetable Research Farm trial. Treatment did not affect mean incidence of yellow shoulder, but it did affect mean incidence of sunscald. The trellising treatment had the lowest and reduced in-row spacing treatment had the second lowest mean incidence of sunscald.

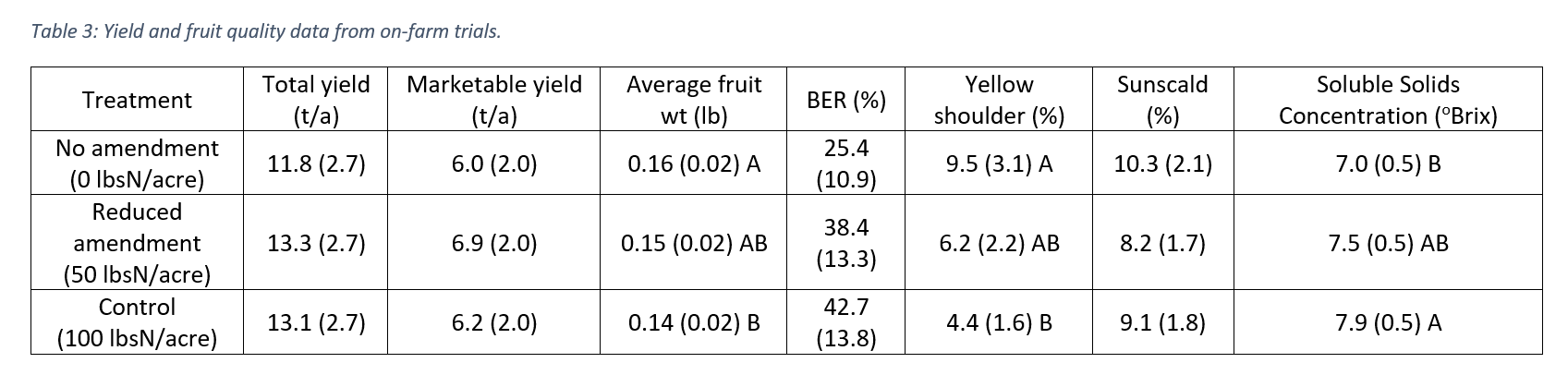

Results of the on-farm trials are presented in Table 3. Treatment did not affect mean total yield or mean marketable yield. However, it should be noted that at one of the on-farm trials, there was a substantial increase in yield when fertilizer was applied. This field was former pasture and had very low phosphorus concentration. Thus, it is possible that on certain sites, fertilizer does improve yields. Treatment did affect mean average fruit size, with the no amendment treatment having larger fruit than the control. Fertilizer application treatment affected mean incidence of yellow shoulder; the control had half the yellow shoulder incidence than the no amendment treatment. Treatment also affected mean soluble solids concentration (sugar) with the control having a higher mean soluble solids concentration than the no amendment treatment.

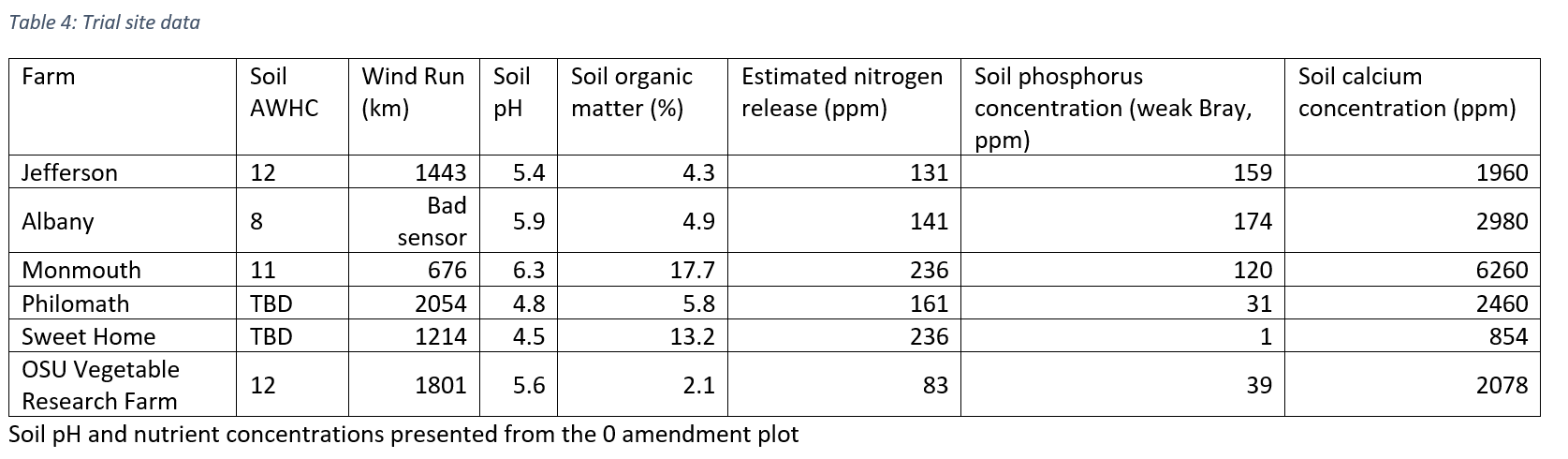

Site data is presented in Table 4. Farms differed considerably in soil and climate characteristics. Most farms had an available water holding capacity (AWHC) of 8 inches or greater. AWHC is important when dry farming, as the amount of water the soil can hold correlates with total yield. Some farms had almost no wind while others were very windy. Some farms had very little soil fertility while others were extremely fertile.

*TBD soil cores were submitted and we are awaiting analysis and results.

Finally, six farms trialed the BER toolkit independently. We did not collect yield or fruit quality data on these sites, but they do offer an opportunity to see what farmers thought about the treatments. Three of the six farmers reported that the tools that they implemented resulted in a decrease in BER. The other three farms reported no effect. One farm that had found reduced BER from the corn shelter also had lower marketable yields from the corn shelter. This was due to the shelter blowing over onto the tomato crop during a storm. Farmer survey data is presented in Table 5.

Year 1 Discussion (2023):

BER incidence at the OSU Vegetable Research Farm was very low during the 2023 growing season, and this may explain why we were not able to detect many treatment differences. We believe that the low BER incidence at the Vegetable Research Farm was due to the plant being less drought stressed, though we are unsure why they were less drought stressed this year than in previous years. Low BER was not the only way that the VRF trials differed from the on-farm trials. There was also higher yields, larger fruit, a higher incidence of yellow shoulder, and fruit had lower SSC. This may have been the result of careful soil prep in addition to lower soil nitrogen concentrations. However, we were able to detect an effect of some of the treatments. We will present the effect of each of the treatments.

Sheltering – Sheltering with blocks of corn did not appear to have much of an effect on BER in tomato at the OSU Vegetable Research Farm in 2023. This may be in part because the corn plots were too small to block the wind effectively. Wind run was also active from the south and west. However, additional plots within the control and sheltering treatments were harvested in an attempt to test the effect of distance from the corn on BER incidence. While distance from the corn did not affect BER incidence, when all of these plots were included in the analysis a small but statistically significant effect was detected (1.2% BER in sheltered plots vs. 1.6% BER in the control plots). Italian dry farmers reportedly intercrop tomatoes with corn (Castronuovo et al. 2023).

Fertilizer application – The effect of fertilizer application was tested in both on-farm trials and at the OSU Vegetable Research Farm. We found some interesting results. First, increasing fertility appears to increase incidence of BER but it also decreased incidence of yellow shoulder. The optimum amount of fertility to apply is probably site dependent, with current soil nutrient levels and degree of sheltering from the wind having some effect. Fertilizer application also affected fruit weight and soluble solids concentration. It may be that increasing fertilizer application causes plants to use water less efficiently, and that the decrease in fruit size and increase in soluble solids concentration is a result of the plants being more drought stressed.

In-row spacing – Decreasing the space between plants decreased the incidence of sunburn. Because the plants were closer together, it is possible that fruits were better covered by foliage.

Trellising – These plots had the best results, with higher marketable yields, increased average fruit size, and reduced sunscalding. Trellising may have prevented sunscald by improving coverage. Plants that were allowed to sprawl would occasionally have vines break under the weight of the fruit, allowing light to penetrate the canopy. We expected that trellising would increase BER incidence, but this result was not observed.

Year 2 Results (2024):

In our second year of trials we tested the interactions between treatments, added a pre-drought stressed seedling trial, and expanded the trials to more farms to deal with the issue of low BER at the VRF. Here are our results:

BERTK experiments:

In 2024 we were able to collect wind data from the centers of both the control and sheltered main plots. This allowed for us to compare the effectiveness of the different crops (Table 6). Overall, sorghum and broomcorn appear to be the most effective, while corn and sunflowers are the least effective.

| Farm | Crop | Windrun in control (km) | Windrun in shelter (km) | Windrun blocked by shelter (km) | BER in control (%) | BER in shelter (%) |

| VRF | Oaxacan Green corn | 14,294 | 13,428 | 866 | 1% | 2% |

| LB1 | Oaxacan Green corn | 3,700 | 3,343 | 357 | 3% | 3% |

| Farm 2 (Jefferson) | Oaxacan Green corn | 11,792 | 10,092 | 1,700 | 3% | 3% |

| Farm 3 (Albany) | Sorghum | 14,213 | 9,823 | 4,390 | 31% | 26% |

| Farm 4 (Monmouth)2 | Sunflowers (branching) | 9,750 | 8,453 | 1,297 | 7% | 19% |

| Farm 7 (Philomath) | Broomcorn | 14,010 | 11,876 | 2,134 | 25% | 21% |

1Wind run data collection at LB started on July 11 due to a faulty sensor.

2Symphylans were present in the control but not the shelter plots. Symphylans may have reduced BER incidence by decreasing growth.

Treatments and their interactions affected yield and fruit quality across the farms (Table 7). Density often had an effect on yield and fruit quality, affecting mean average fruit weight, mean BER incidence, mean necrotic BER incidence, mean yellow shoulder incidence, and mean sunscald incidence (at α = 0.05). However, for certain response variables there were interactions between density treatments and the other treatments. There was a fertility treatment × density treatment interaction in their effect on mean necrotic BER incidence. There was also a fertility treatment × density treatment × sheltering treatment in their effect on mean average fruit weight and mean yellow shoulder incidence.

Table 7. Statistical significance of different treatments or interactions.

|

|

Fertilizer Treatment |

Density Treatment |

Shelter Treatment |

Fertility × Density |

Fertility × Shelter |

Density × Shelter |

Fertility × Density × Shelter |

|

Total yield |

NS |

0.058· |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

|

Unblemished yield |

NS |

0.075· |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

|

Average fruit weight |

NS |

<0.001*** |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

0.014* |

|

BER incidence |

0.090· |

<0.001*** |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

|

Necrotic BER incidence |

NS |

0.006** |

NS |

0.024* |

NS |

NS |

0.055· |

|

Yellow shoulder incidence |

NS |

<0.001*** |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

0.029* |

|

Sunscald incidence |

NS |

0.017* |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

Results from F-tests (yield and average fruit weight) or chi-squared tests (incidence of BER, yellow shoulder, and sunscalding).

Increasing the planting density was found to increase BER incidence and decrease sunscalding incidence (Table 8). Increasing the planting density also increased necrotic BER incidence, but only for the high fertility plots. Increasing planting density also tended to decrease average fruit weight and decrease incidence of yellow shoulder, but the amount of change was also affected by other treatments. For example, yellow shoulder was most affected by planting density for the low fertility, no shelter plots.

Table 8. Effect of treatments and interactions on mean average fruit weight, BER incidence, necrotic BER incidence, yellow shoulder incidence, and sunscalding incidence in 2024 trials.

| Average fruit weight (lbs) | BER incidence (%) | Necrotic BER incidence (%) | Yellow shoulder incidence (%) | Sunscald incidence (%) | |

| Low density | 5.3 B | 3.4 A | |||

| High density | 9.7 A | 2.6 B | |||

| High fertility x low density | 1.1 B | ||||

| Low fertility x low density | 1.2 B | ||||

| High fertility x high density | 2.4 A | ||||

| Low fertility x high density | 1.3 B | ||||

| High fertility x low density x no shelter | 0.178 AB | 26.7 ABC | |||

| Low fertility x low density x no shelter | 0.186 A | 30.1 A | |||

| High fertility x high density x no shelter | 0.171 ABC | 21.0 BCD | |||

| Low fertility x high density x no shelter | 0.165 B | 17.0 D | |||

| High fertility x low density x shelter | 0.180 AB | 26.1 AB | |||

| Low fertility x low density x shelter | 0.178 AB | 26.1 AB | |||

| High fertility x high density x shelter | 0.155 C | 19.4 CD | |||

| Low fertility x high density x shelter | 0.169 ABC | 20.7 BCD |

Pre-drought stressed trials

We were able to apply irrigation treatments in the greenhouse to "pre-drought stress" the seedlings in 2024. We thought this may help to prevent BER by activating "drought-stress memory," which is the phenomenon that plants will respond to drought differently if they have experienced it before. This may also affect the root to shoot ratio and improve out-planting success, as is seen in the forestry industry. However, there was little to no effect of nursery irrigation practices on the yield and fruit quality of the tomatoes. There may have been a small effect on mean yellow shoulder incidence, with the reduced-irrigation plants having slightly lower mean yellow shoulder incidence; the effect was small but significant (Table 9).

Table 9. Effects of nursery production treatment on dry-farmed tomato yield and fruit quality during the 2024 growing season.

|

Treatment |

Total yield (t/a) |

Unblemished yield (t/a) |

BER incidence |

Yellow shoulder incidence |

Soluble solids concentrations (oBrix) |

|

Control (irrigated at 80% of field capacity) |

20.7 |

10.6 |

12.1 |

21.8 A |

7.9 |

|

Reduced irrigation (irrigated at 20% of field capacity) |

21.4 |

12.1 |

11.2 |

18.7 B |

7.8 |

|

Single drought (irrigated at 80% of field capacity, but water withheld for 4 days before planting) |

20.5 |

10.9 |

12.0 |

19.6 AB |

7.9 |

Farm data:

In addition to presenting the data by treatment, we also analyzed farm performance. Averages for total yield, BER incidence, soluble solids concentration, taste test results, and root length density at 2 and 3 foot for farms are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Average results for selected response variables by farm.

| Farm | Total yield (t/a) | BER incidence (%) | Soluble solids concentration (oBrix)1 | Taste test results (scale of 1-5) | Root length density (2 ft) | Root length density (3 ft) |

| VRF | 19.9 | 1 | Not tested | 3.3 | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| LB | 25.0 | 3 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 0.47 | 0.34 |

| Farm 2 (Jefferson) | 31.5 | 3 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 0.52 | 0.53 |

| Farm 3 (Albany) | 27.5 | 29 | 8.7 | 4.0 | 0.73 | 0.63 |

| Farm 4 (Monmouth) | 14.1 | 13 | Not tested | Not tested | 0.38 | 0.22 |

| Farm 7 (Philomath) | 14.8 | 23 | 7.4 | 3.6 | 0.60 | 0.35 |

1Data from PDS plots, BERTK samples still need to be processed.

Year 2 Discussion (2024):

Sheltering: Wind speed was not greatly affected by intercropping, except for with sorghum and broomcorn. The effectiveness of a shelter is generally controlled by its porosity, height, and distance from the crop. In addition, the growth rate of the shelter crop could affect how quickly it is able to block wind. Finally, certain sites tended to have more wind coming from directions that the shelter crop did not block.

Treatment effects: The 2024 findings add further nuance to previous studies in a number of ways. First there is the increase of BER at higher planting densities. Previous studies have found that BER decreases as planting density increases. However, our results show that at a certain point this trend reverses. Similar to this, there was no effect of fertilizer on yellow shoulder incidence in 2024, but this may have been because we did not include a "no amendment" treatment in the trials.

Interactions: Some interactions between treatments were detected. These tended to show that certain treatments only had an effect in combination with another treatment. For example, necrotic BER was increased by high fertility, but only at the high planting density. Additionally, planting at a high density decreased yellow shoulder, and this effect was greater in lower fertility plots. High density low fertilizer plots seem to perform the best, and the smaller fruit from these plots may be more desirable as farmers are reported to want intensely flavored, small fruit (Socolar et al. 2024).

Pre-stressed seedlings: There was no obvious effect of pre-stressing the seedlings on yield and fruit quality, except for a small but statistically significant effect on yellow shoulders. Physiologically, drought-stressed tomato plants recover within three days of rewatering, especially when in the seedling phase (Hao et al. 2019). This includes a reduction in antioxidant activity. Perhaps tomato lacks the drought-stress memory that has been reported for other plants. Pre-stressed seedling may have an application though. First, by deficit irrigating the seedlings, farmers can slow their growth for delayed planting, while knowing that yield and fruit quality will be unaffected. Second, these seedlings may be better suited for outplanting, with a higher survival rate under suboptimal conditions (droughty soils during planting).

Research outcomes

Dry farming has been widely adopted for certain crops in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, and this is increasingly true for vegetables. However, dry-farmed tomato growers continue to struggle with a) achieving the flavor intensity that they are pursuing and b) controlling blemishes, including BER, yellow shoulders, sunscalding, and cracking. OSU researchers have shown that flavor and blemishes can be affected by site selection, variety selection, and vegetable grafting. In this project, we have focused our attention on management practices. If farmers are able to control blemishes in dry-farmed tomato, this will help them profitably produce crops without irrigation. This will improve their livelihoods while also reducing the burden on surface and ground water resources.

The project team continues to believe the in efficacy of the BER toolkit as a management strategy for reducing BER in dry-farmed tomato. However, the trials have allowed for us to refine our recommendations.

Sheltering the crop from the wind is expected to decrease crop drought stress, increase marketable yields, and reduce BER incidence. However, the effect of intercropping on dry-farmed tomato is dependent on the shelter crop, with sorghum and broomcorn performing better than sunflowers and maize. This may be because certain crops are better at blocking the wind. Future work could also assess the impact of windscreens, which would start to block the wind immediately, would not take away growing space from the crop, and could be moved if wind direction changed.

Optimum fertilizer is site dependent, though on most sites excess fertilizer results in an increase in BER. Fertilizer applications affect other tomato quality measures, including incidence of yellow shoulders, average fruit weight, and soluble solids concentrations. This leaves growers with a paradox, as they want to grow intensely flavored tomatoes without BER.

Planting rows at a tighter in-row spacing appears to reduce incidence of sunscalding. While in a 2019 trial BER was reduced and yields increased by planting at a higher density (2,178 plants/acre compared with 1,089 plants/acre), 2024 research showed that this trend may reverse at higher densities (4,149 plants/acre compared to 2,074 plants/acre). There was also an interaction between fertilizer application and planting density on necrotic BER incidence. This shows why it is important for researchers to test the interactions between management treatments.

Pre-drought stressing the seedlings in the nursery had little effect on yield and fruit quality after planting. Yield, BER incidence, and SSC remained unchanged, though there was some evidence for an effect on yellow shoulder incidence. Future work should determine if these pre-stressed seedlings are better equipped to survive outplanting under unideal conditions.

Finally, trellising increased marketable yields and average fruit weight. However, it is still possible that by elevating the crop it is more exposed to the wind, which may increase drought stress.

In 2025, we are going to repeat our 2024 field trials. This will allow for us to collect more data on the BER toolkit treatments and repeat our pre-drought stressed seedling trials to see if the effect on yellow shoulders is present for multiple years. We are also almost prepared to submit our manuscript on the 2023 research trial to HortTechnology.

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

Our educational objectives are to: (A) educate farmers and agricultural professionals on multiple theories regarding the direct causes of BER, (B) educate them on the BER Toolkit as a tested means of controlling BER for dry-farmed tomatoes, and (C) to educate marketers and consumers on the value of dry-farmed produce, especially tomato. In addition to these goals, this project also supported more general education and outreach regarding dry farming.

The following education and outreach activities were conducted as part of the BER Toolkit project:

August 23rd, 2023 Oak Creek Field Day: 60 participants came to learn about the BER Toolkit project and taste dry-farmed melons (media).

August 31st, 2023 Field Day: 70 participants were able to tour the main Vegetable Research Farm trial, learn about the BER Toolkit project, and participate in a tasting of all of the different BER Toolkit treatments (media).

September 16, 2023 Tomato Festival: The BER Toolkit project funded a dry-farmed tomato festival at Wellspent Market in Portland, OR. ~325 contacts (website).

February 1st, 2024 Project Team Meeting: 4 of the 5 farmers who hosted fertilizer trials in 2023 attended to discuss trial results, the report, and plan for 2024.

February 7th, 2024 Dry Farming Collaborative Winter Convening: We gave a 15-minute presentation on the BER Toolkit at the 9th annual Dry Farming Collaborative Winter Convening (video). 198 collaborative members were in attendance. 17 of these participants filled out a survey on the BER Toolkit after the convening (see results).

February 17th, 2024 Small Farms Conference: We gave a 15-minute presentation on the BER Toolkit and our 2023 trial results at the Small Farms Conference. This was the same presentation as the one given at the DFC winter convening. 116 participants were in attendance. One participant filled out a survey on the BER toolkit after the conference.

August 14th, 2024 Dry farming field day at Oak Creek Center for Urban Horticulture: 60 farmers attended this event that included a taste test to demonstrate the effects of site on flavor intensity. Additionally handouts on controlling blemishes in dry-farmed tomato in both English and Spanish and marketing materials were distributed to the farmers.

August 21st, 2024 Dry farming field day at VRF: 71 farmers attended this field day that included a tour of the BER toolkit trial, a tour of a dry-farmed tomato variety demonstration garden, and a taste test to demonstrate the effects of treatments and site (i.e. terroir) on flavor intensity. Additionally handouts on controlling blemishes in dry-farmed tomato in both English and Spanish and marketing materials were distributed to the farmers.

September 8th, 2024 Variety Showcase: We tabled at the Variety Showcase put on by the Culinary Breeding Network in Portland, OR. We conducted a taste test with tomatoes from five of the different farms to test the effect of site on flavor intensity (i.e. terroir). A chef also prepared two of the tomato varieties from our trials, Early Girl and Dirty Girl. Approximately 670 people attended this event, 60 participated in the taste test.

September 9th, 2024 Dry-farmed tomato retailer/wholesaler focus group with Organically Grown Company and NW alternative co-ops. Sixteen retailers and wholesalers from around the Pacific Northwest came to our field trial at farm 7 to taste different tomato varieties from two different farms (the two farms that performed highest and lowest in tomato soluble solids concentration in 2023). The goal was to highlight high-performing varieties while also demonstrate the effect of site selection (i.e. terroir) on dry-farmed tomato flavor intensity. Surveys were collected but unfortunately there was not the same enthusiasm for the tomatoes as in previous focus groups showcasing dry-farmed melons. This event was co-hosted by the Dry Farming Institute.

September 11, 2024 Small Farms School: We presented on the production and marketing of dry-farmed melons to 19 students. This session included an introduction to dry farming, recommendations of the best melon cultivars for dry farming and how to determine if they are ripe, production strategies to maximize yields and establishment, and marketing materials and information including the controlling blemishes in dry-farmed tomatoes handout in English and Spanish.

September 14, 2024 Tomato Fest: We produced the Tomato Fest for a second year. Two commercial farms and one other OSU research team also participated, along with food and souvenir vendors. We provided educational and marketing materials on dry farming and also provided dry-farmed tomato and melon tastings. The melon variety 'Bella' was very popular, and multiple people tried to buy them from us. The number of interactions was not collected but we estimate around 300 people attended (website).

November 11, 2024 Deep Roots Coalition Trade Tasting: We tabled at a wine tasting event focused on wine produced from dry-farmed grapes. We displayed research articles, distributed posters to the public, and recorded interviews with four different wine grape growers (Rory Williams, John Paul, Phil London, and Robert Lauer).

Additional education projects:

Created the BER toolkit website on February 13, 2024. URL: https://horticulture.oregonstate.edu/article/blossom-end-rot-toolkit-dry-farmed-tomatoes. This website includes our report on the first year of trials, the Controlling Disorders in Dry-farmed Tomato handout in both English and Spanish, and a recording of the 2024 and 2025 Dry Farming Collaborative Winter Convening presentations.

Created the Controlling Disorders in Dry-farmed Tomato handout (English and Spanish).

Printing: We printed 500 posters to promote dry-farmed tomatoes and melons.

Survey results from February 2024 Winter Convening and Small Farms Conference:

Of those surveyed, 16/17 reported that they now understood that there are multiple theories regarding the direct causes of BER.

Of those surveyed, 4/17 reported that they intended to grow dry-farmed tomatoes after learning about our project. An additional 8/17 reported that they already grew dry-farmed tomatoes and 4/17 reported that they did not grow dry-farmed tomatoes, but intended to before they learned about the project.

Of those who said that they had grown dry-farmed tomatoes before:

6/8 said that they were interested in using sheltering to control BER

7/8 reported that they were interested in applying fewer soil amendments to control BER

7/8 reported that they were interested in planting at a different spacing to control BER, while 1/8 wanted to see more data

1/8 reported that they were interested in using tomato grafting to control BER, while 1/8 wanted to see more data

3/8 were interested in pre-drought stressing seedlings to create drought stress memory, while 3/8 wanted to see more data

Of those whose had not grown dry farmed tomatoes before:

6/8 were interested in growing a shelter crop to prevent BER, while 1/8 wanted to see more data

6/8 were interested in applying fewer soil amendments to control BER, while 2/8 wanted to see more data

6/8 reported that they were interested in planting at a different spacing to control BER

1/8 reported that they were interested in using grafting to control BER

4/8 reported that they were interested in pre-drought stressing seedlings to create drought stress memory, while 2/8 wanted to see more data.

Of those who grow dry-farmed tomatoes, 4/8 report that they already market dry-farmed tomatoes, 1/8 reported that they intended to market dry-farmed tomatoes before seeing the presentation, and 2/8 reported that they intended to after seeing the presentation.

Of those who did not grow dry-farmed tomatoes, 1/8 reported that they intended to market dry-farmed tomatoes before seeing the presentation and 5/8 reported that they now intend to market dry-farmed tomatoes after learning about the project.

Of those surveyed, 7/17 were interested in using the marketing materials to help them sell dry-farmed tomatoes.

In summary, of all those who filled out a survey, 16/17 reported that they intended to change a practice, whether that was adopting one of the tools or growing or marketing dry-farmed tomatoes.

Survey Results from August 2024 Vegetable Research Farm Field Day:

Unfortunately only 8 of the 71 participants in the field day filled out the survey. Two questions were answered:

- “Did you learn new approaches to dry farming?” Yes: 8 (100%)

- “Will you apply new knowledge to farm or garden, if applicable?" Yes = 83%, Maybe = 17%, No = 0%

Survey Results from September 2024 Focus Group:

11 retailers and wholesalers participated in our focus group. We wanted to demonstrate to them the effects of Terroir on dry-farmed tomatoes, with the hypothesis that they would prefer the commercial farm (highest soluble solids concentration) to the research farm. We included many of the varieties that we recommend to growers, and collected descriptors from them.

| Variety | Research Farm Descriptors | Commercial Farm Descriptors | Winner |

| Cosmonaut Volkov | Very juicy; higher acidity; great color, good texture, light on flavor, good acidity; a little softer texture, hot mushy, good classic tomato flavor; sweeter, mild, less acidic; acidy; a great pasta sauce, great color; good flavor, more seedy; slightly higher flavor concentration | Dark in color; floral finish, thick skin; great color, good texture, light flavor, good acidity; soft, a little sweeter flavor; warm, sweet, dark flesh; light flavor; less seedy, cool inside flesh, bleh flavor | Tie |

| Damsel | Less acidic, more juicy; rich flavor, low acidity; soft palate, medium flesh; sweet, tasty; sweeter, mild, less acidic; good saucer, base tomato flavor; tomato sauce, flavor wonderful | Really yummy, my favorite; rich flavor, low acidity; bold, fleshy, juicy, balanced, more vibrant; sauce tomato, nice acid; sweet but umami, more concentrated flavor; juicy; tomato sauce, flavor wonderful |

Commercial Farm (+2) |

| Dirty Girl | Not super flavorful; meaty, thick, less acid, bland finish; nice all around flavor, good appearance, good texture; a hint of tomato paste, like tomato soup, good texture; rich, umami, thick flesh, wetter; intense, great for a sandwich; fine, firm, nice texture | Not super flavorful; more complex profile, acid front, sweet finish; bright start, soft finish, mild; nice all around flavor, good appearance, good texture; tomato soup, great texture; sweeter, less umami, soft flesh; almost a chocolatey taste; fine, firm, nice texture | Commercial (+1) |

| Early Girl | Ok; higher acidity; soft meat, very juicy, soft acid; good appearance, good color, mellow flavor; lighter flavor, juicy, refreshing, subtle acid, good texture; more umami, more complex flavor, thicker flesh; floral; great flavor, nice eating experience; brighter acid | Thick skin; deep red flesh, denser texture, flatter finish; lush, juicy, bright; more balanced flavor; more tomato tang compared to research farm, lighter lemony notes, good texture; sweeter, simple sweet, softer, more water; sweet rich flavor; great subtle flavor; richer, depth, appears more ripe | Commercial (+3) |

| Matina | More acidic, true tomato flavor; mild, sweet; juicier, more soft flesh, softer acid; nice bright flavor, good balance of acid and sweet; light tomato flavor; strong flavor, sweeter, thicker skin, squishier texture; less dominant flavor; sweeter, more dense; better texture, filling flavor | Skin thicker; less sweet; bright flavor, thin skinned, preferred over research farm; light skinned, bright acid; nice bright flavor, good balance of acid and sweet; more flavor than research farm, nice tang; mild, crunchy; beefy, savory; not very flavorful; fleshy | Research (+1) |

| Piennolo del Vesuvio | More flavorful than commercial; thick skin, a little acid; mild flavored, medium firm skin; washed out flavor, little/no acid, looks great; mild tomato flavor, great texture for salad; mild, sweeter; thick skin, light punchy flavor; not as bright, kind of dull | Not very acidic; thick skin, a little acidic; balanced acid and sugar; thick skin, subtle flavor, medium flesh, soft acid; washed out flavor, little/no acid, looks great; has a tarter taste, reminds me of a bloody Mary; thick skin, more acidic, more umami, beautiful flesh; light flavor, maybe good for drying; more acid; skin more bitter | Tie |

*Semicolons indicate a change in the taster, commas indicate a new note. Winner was based on comparing notes for the research farm and commercial farm for each taster, awarding 1 point for each time a taster indicated a preference.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

Farmers are open to the learning about alternative theories as to the direct causes of BER. Unfortunately, many publications on the physiological disorder strictly focus on the theory that calcium deficiency is the direct cause. Even if this theory is ultimately more correct, it may cause farmers to pursue solutions that have no effect on their crop. For example, those who promote the calcium theory of BER often claim that while calcium is the direct cause of BER, this is not due to insufficient calcium in the soil. Instead, BER is due to their being insufficient water to move the calcium, an excess of other cations, or some other factor that is limiting calcium uptake and allocation to the fruit. However, when a farmer hears that calcium is the cause, they will assume that they can fix BER by adding more calcium to the soil. We propose that rather than focusing on generalizable theories, those who conduct educational and outreach activities should focus on presenting methods that actually control BER and help to educate farmers on the contexts in which these practices actually work.

In the case of our project, we promote treatments like sheltering to control BER. We hypothesize that sheltering will reduce wind, which will in turn reduce evapotranspiration and drought stress. However, there are contexts in which sheltering will have little effect. One of our 2023 on-farm trials was an urban farm with very little wind measured (see Table 4, Monmouth). At this farm, planting a shelter will probably have no effect on BER incidence. However, this site had relatively high BER, likely induced by the large amount of compost that had been applied to the field. Thus, for this farmer, we would recommend reducing the amount of fertilizer and compost applied, or opening a new field where there is lower organic matter.

In summary, our aims are to help farmers understand practical tools that they can use to manage physiological disorders, rather than confusing them with theory. We also want to contextualize these tools so farmers understand the conditions that make each of them appropriate.

- Methods of dry-farmed tomato production.

- Multiple theories on the direct causes of BER.

- Tools of the BER toolkit and their efficacy.

Farmers were taught methods of field prep, amendments, planting, and crop management for dry-farmed tomatoes. Of the farmers who completed the survey, eight reported that they grew dry-farmed tomatoes, four reported that they did not grow dry-farmed tomatoes but wanted to grow them prior to learning about the project, four reported that they intend to grow dry-farmed tomatoes after what they learned from the project, and one reported that they did not intend to grow dry-farmed tomatoes.

Of the farmers surveyed, 16 reported that they now had a better understanding of the multiple theories as to the direct causes of BER and one reported being more confused about the causes of BER after learning about the project.

After learning about the project, 12 farmers reported that they wanted to try growing a shelter crop, 13 farmers reported that they wanted to try reducing the amendments they apply, 13 reported wanting to plant dry-farmed tomatoes at a tighter in-row spacing, two farmers reported that they wanted to graft tomatoes to reduce drought stress, and seven farmers were interested in trying to prestress seedlings in the nursery prior to planting.