General Information

State

County

Are you a Farmer or Rancher?

- Yes

Type of Grant Project

- Team of Two (2 farmers/ranchers)

Team or Group Project Members

Proposed Start Date

Proposed End Date

Grants Funds Requested

Have you submitted this, or a similar proposal, to NCR-SARE before?

- No

If you answered Yes, provide the requested details.

I'm not sure if we were supposed to answer yes or no here. We haven't submitted this proposal before, but Ohe.laku did receive a Farmer Rancher grant that really got our group going: FNC 16-1046 "Traditional Fertilizer, Modern Applications for Iroquois White Corn". We studied the impacts of fish emulsion on White Corn with other farmers on the Oneida Reservation. We found that fish emulsion had a positive impact and was an appropriate application of a traditional practice in a modern context. We still use fish emulsion to fertilize our fields and learned a lot about soil science. We are now interested in pursuing the next level in sustainable production and studying low- and no-till approaches to growing ancestral corn.

Practices

- Production Systems (includes agroecosystems, aquaponics, holistic management, hydroponics, integrated crop and livestock systems, organic agriculture, permaculture, etc.)

Commodities

- Agronomic

Grant Proposal

Project Abstract

Two Tribal farms in Northeast Wisconsin - Ohe.láku on the Oneida Reservation and Menīkānaehkem on the Menominee Reservation - grow Indigenous (heirloom) corn with volunteer labor to provide traditional foods to their Tribal Nations. They have identified their production challenges as weed pressure, costs of organic fertilizer, unavailability of labor, and inherited poor soil health.

The silver bullet solution may lie in cover cropping and reduced tillage. While not innovative in and of itself, these practices haven’t been studied with Indigenous corn. This project bridges two worlds of understanding to fill that gap - Indigenous grassroots farming and extension research. Ohe.láku and Menīkānaehkem are partnering with the UW-Madison and Outagamie County Land Conservation to understand the optimal applications of these practices for two Indigenous corn varieties. We estimate that results will demonstrate weed suppression and improved soil fertility and microbial diversity. These results will reduce fertilizer inputs and suppress weeds, saving money and labor time of Tribal members, allowing for Ohe.láku and Menīkānaehkem to focus on other aspects of their food sovereignty work.

Through outreach, we are hoping to build upon the traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples and create a connection from healthy soils to healthy food to healthy people.

People

The team for this project centers indigenous knowledge and relationships with allies. Two indigenous, grassroots farms utilizing sustainable practices are involved in the project. Ohe.láku (“Oh-hey-LAH-goo”), meaning “Among the Cornstalks” in Oneida, is a cooperative that farms ancestral varieties of corn, beans and squash on 30 acres on the Oneida Reservation. The primary crop is Tuscarora White Corn, which will be studied in this project. Ohe.láku is headed by Laura Manthe, an Oneida citizen and the Director of the Oneida Nation Environmental Resources Board. She’s aided by her daughter, Lea Zeise, who also works as the Agriculture Program Manager for a Tribal non-profit, United South and Eastern Tribes. Ohe.láku’s membership includes 15 families, however, the cooperative reaches hundreds of community members each year through on-farm events and youth education programs.

About 40 miles north lies the Menominee Reservation and the food sovereignty-focused non-profit Menīkānaehkem (“Minnie - kahna - kem”). Cherie Thunder (Menominee) heads up Menīkānaehkem’s farm and outreach operations, overseeing ancestral corn, beans, squash, and other produce on 80 acres of Menominee Trust Land. Cherie had been volunteering with the food sovereignty initiative for 3 years before taking on the role of Farm Manager. This year, Cherie led Menīkānaehkem’s youth cohort in their first season of planting and maintaining a garden and assisted with organizing a collaborative starter plant growing operation and giveaway. Cherie’s primary focus is involving the community in sustainable and culturally-relevant farming practices.

Also on the team are Dr. Erin Silva, Associate Professor and Organic and Sustainable Cropping Systems Extension Specialist, and Daniel Hayden, PhD student, in the Department of Plant Pathology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Dr. Silva’s research focuses broadly on organic agriculture with specialization of reduced tillage in grain systems. Daniel, co-advised by Dr. Silva and Soil Ecologist Dr. Rick Lankau, is focused on understanding the role of soil-microbes in Indigenous agricultural systems. Daniel seeks to use his own Indigenous background (Comanche) to collaborate with and elevate the perspectives of Indigenous growers in Wisconsin.

Other project partners include Greg Baneck, Outagamie County Conservationist, who will continue working in collaboration with Oneida Nation Environmental Health, Safety, Land and Agriculture Division to provide technical assistance and, when possible, equipment utilization for field preparation and seed drilling.

Project Objectives

- Evaluate the usefulness of 3 cover crops (chicory, plantain and dutch white clover) interseeded with Tuscarora White Corn and Bear Island Flint Corn through field testing

- Prepare and evaluate usefulness of roller crimping of Aroostook Rye with these two corn varieties

- Share findings through field days, social media, a conference presentation, and scientific publications

Measuring benefits and impacts

- Environmental Sustainability

- Improved soil quality/health

- Production and Production Efficiency

- Improved crop production and/or production efficiency

- Social Sustainability

- Improved quality of life

How will you measure benefits and impacts?

| Benefits | What will be measured | How benefits will be measured |

| Improved soil quality | Soil loss | Use a soil erosion stick to compare soil loss before and after using cover crops |

| Improved soil quality | Soil and root microbial diversity | Use DNA sequencing technology to observe composition of microbial communities (in collaboration and funded via UW-Madison) |

| Production Efficiency | Weed control effectiveness | Sample areas of each trial area to determine germination rate and biomass of cover crops in comparison to weed biomass |

| Production Efficiency | Yield and proportion of seed corn to "soup" corn | Evaluate cobs based on genetic expression into seed and "soup" grade groups; Measure weight of each group to compare between trials (seed corn expresses ideal traits and development; the higher proportion of seed corn, the more valuable the harvest) |

| Quality of Life (*in commercial operations, this may be considered a Cost of Production Benefit) | Hours of production labor | Compare equipment hours spent on conventional and trial field sections |

Activities and Timeline

|

DATE |

PROJECT ACTIVITY |

WHO PARTICIPATES |

|

January 2021 |

Meeting to review experimental design |

Lea Zeise, Laura Manthe, Cherie Thunder, Tony Kuchma, Daniel Hayden, Erin Silva, Greg Baneck |

|

April 2021 |

Refresh planting plan. Conduct soil test at farms. Add amendments to field. Purchase cover crop seed. |

Tony, Lea, Cherie, Erin, Daniel |

|

June 2021 |

Plant corn the first week of June and interseed with cover crops (dutch white clover, chickory, plantain) the subsequent week. |

Tony, Lea, Daniel, Cherie |

|

June - Sept 2021 |

Sampling: · Soil samples measured for fertility and microbial diversity (to be completed through partnership with UW-Madison) · Cover crop germination and biomass · Corn height |

Daniel and Tribal student interns |

|

August 2021 |

Finalize plans for planting rye. |

Lea, Tony, Cherie, Daniel |

|

Sept 2021 |

Sample corn biomass and yield. Retrieve final soil and cover crop biomass samples. Plant rye. |

Erin, Daniel, interns, Tony, Cherie |

|

Oct-Dec 2021 |

Finish analysis on 2021 field season. Report results to farms. |

Daniel and research assistant |

|

April 2022 |

Pre-planting meeting. Add amendments to field. |

Tony, Lea, Cherie, Erin, Daniel, Greg |

|

June 2022 |

Plant corn with three methods: drill into rye, interseed with cover crops, plant conventionally |

Tony, Lea, Daniel, Greg |

|

June - Sept 2022 |

Sampling: · Soil samples measured for fertility and microbial diversity · Cover crop germination and biomass · Corn height |

Daniel, interns |

|

Sept 2022 |

Measure corn & weed biomass and yield. |

Daniel Hayden, interns |

|

Oct-Dec 2022 |

Finish analysis on 2022 season. Report results to farms. |

Daniel, Research Assistant |

Materials and methods

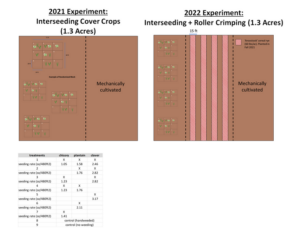

There will be two field sites at Menīkānaehkem on the Menominee Reservation and at Ohe.láku on the Oneida Reservation. At each site we will have 2 years of field experiments, 2021 with interseeding cover crops on a 1.3 section of the field, then in 2022 with a duplicate interseeding and roller crimping experiment on another 1.3 acre section (prepared in 2021).

In 2021, we will interseed cover crops with Tuscarora White Corn for Ohe.láku and Bear Island Flint Corn for Menīkānaehkem. In early June, corn and cover crops will be sown together, with corn planted on 36” rows at typical populations (Figure 1A). Cover crops interseeded will include treatments of chicory, plantain, and dutch white clover in factorial combination (Table). Two control treatments will also be included (hand-weeded control and non-weeded control). Along with this, we will have .5 acre sections mechanically cultivated for comparison of labor hours.

In August 2021, we will establish plots for the roller-crimping experiment - 1.3 acres at Ohe.láku and 1.3 acres at Menīkānaehkem - by preparing the soil to integrate crop residue and eliminate weeds. ‘Aroostook’ cereal rye (3 bu/ac) will be planted in the beginning of September 2021. In the first week of June 2022, we will plant corn directly into the roller-crimped rye. This will be in par with a duplicate interseeding experiment.

Standard yield measurements will be made in tandem with another method which separates out the desirable cobs. The farms use this process to save seed, and it provides insights into the proportion of seed grade corn to “soup” grade corn, or that which is eaten. The ideal ratio would skew towards seed corn, thus the implementation of these reduced tillage practices may affect this ratio based on plant development and health.

Outreach: Sharing project information

| Date | Activity | Who participates |

|

August 2021 |

Host field day / harvest events at interseeded fields. |

Lea, Laura, Tony, Cherie |

| Sept 2021 | Share photos of interseeded trials on Ohe.láku and Menīkānaehkem’s Facebook pages. | Lea, Cherie |

| Jan 2022 | Share summary of initial findings on Ohe.láku and Menīkānaehkem’s Facebook pages. | Lea, Cherie |

|

Aug 2022 |

Host Green Corn harvest event to demonstrate the effectiveness of the roller-crimped rye |

Lea, Laura, Cherie, Tony, Daniel, Erin, Greg |

| Dec 2022 | Share final results on Ohe.láku and Menīkānaehkem’s Facebook page. Submit presentation proposals to Tribal Food Sovereignty Summits. | Lea, Cherie |

Previous research review

The SARE database revealed that there is one Farmer Rancher grant in progress to study interseeding cover with various row spacings of corn, however, the project didn't mention what variety of corn would be studied. There is also a Research and Education grant focused on precision planting winter rye, which is somewhat related to our project, but doesn't study the effects in the same context as the farms in this project. For Tribes throughout the U.S., this context is important because their methods and corn varieties utilized fall outside the spectrum of hybrid or GMO corn grown for profit. Often, Tribal corn varieties are grown for subsistence, trade, or small batch processing for local sale to Tribal citizens. There is also one Graduate Student project assessing cover crops and soil microbial communities, however, the connection to corn is not made.

ATTRA offered some guidance on winter rye, but not in regards to roller crimping it, only mowing, burning, or incorporating it. There was a publication on the row width for corn, with inconclusive results on whether 30" or 60" would produce higher yields.

This project is novel because it compares interseeding with roller-crimping for two Indigenous heirloom corn varieties. It also studies the ratio of seed corn to "soup" corn, which is an important measurement tool for the health of the plant, and therefore the soil.

Contribution to sustainable agriculture

Economic: Though we are not measuring economic benefits, the findings we gather on soil health improvements, yield comparisons, and labor reduction could be applied in a commercial context. Ideally, soil quality and yield will improve while labor and input costs are reduced.

Environmental: Cover crops reduce soil erosion which improves water quality and ecosystem health. They also improve soil quality and microbial diversity, and we are hoping to find that they suppress weeds effectively, leading to fewer passes with a cultivating tractor (fossil fuels emissions) and for some farmers, reduced usage of conventional herbicides.

Social: Connecting soil health to the health of the corn to the health of the people fits well within the Indigenous worldview, where soil and corn are both living entities in reciprocity with people. We are hoping to encourage more Indigenous people to engage in preserving their own heirloom seeds with sustainable agriculture. Beyond Indigenous farms, the reduction of farm labor and overall improvement in ecosystems supports improved recreation by freeing up time and also supporting fish habitats for sportsmen and women in our many streams that wind through farmland across the North Central region.

Letter of Support

Livestock Care Plan

Does this project involve livestock (vertebrate animals only)

- No

Budget and justification

Budget and Justification

| Category | Description | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Materials and supplies | Cover crop seed | $1,500 |

| Materials and supplies | Organic fertilizer | $4,200 |

| Materials and supplies | Sampling Equipment | $190 |

| Materials and supplies | Scale | $210 |

| Personnel | Research Assistant | $5,000 |

| Personnel | Tribal Student Interns | $3,840 |

| Travel | Daniel Hayden & Dr. Erin Silva's Travel to farms for data collection & field days | $2,944 |

| Total: $17,884 | $17,884 | |

| Category | Details/Justification |

|---|---|

| Materials and supplies | Cover crop seed - $1,500 Cover crop seed: average $10/lb * 25 lbs/ac * 1.5 acres * 2 sites * 2 years = $1,500 |

| Materials and supplies | Organic fertilizer - $4,200 $700 / ac * 1.5 acres * 2 sites * 2 years = $4,200 |

| Materials and supplies | Sampling Equipment - $190 Flags for marking field sites, bags for soil and plant samples, tools for sampling (shovels, corers). Bags per field site $20 x 2 = $40. Flags and stakes per field site $20 x 2 = $40. Shovels $15 x 2 = $30. Corers $40 x 2 = $80. |

| Materials and supplies | Scale - $210 Grain scale $80 + Biomass scale $130 |

| Personnel | Research Assistant - $5,000 UW-Madison student hired to assist Daniel Hayden in processing data to improve the turnaround time of results to growers. Working part time for two semesters (250 hrs x $10/hr = $2500 * 2 semesters = $5000) |

| Personnel | Tribal Student Interns - $3,840 2 Local high school students to assist with data collection.: $12/hr * 160 hrs * 2 years = $3840(Youth are already involved in both projects) |

| Travel | Daniel Hayden & Dr. Erin Silva's Travel to farms for data collection & field days - $2,944 Roundtrip: 260 mi to Oneida + 105.75 mi to Menominee = (260 miles +105.75 miles) * .575 * 14 trips = $2944.29 |