2016 Annual Report for FNE15-816

Wet rice organic weed control trials

Summary

Our aim is to evaluate weed control strategies for wet rice cultivation. Erik Andrus served as lead farmer and project director, and Ben Waterman of the UVM Center for Sustainable Agriculture is technical advisor. Ian Gramling was a hired farm worker and also participated in managing the experiment. During the year of 2016, the main part of the proposed work took place. In the preceding year, the groundwork for the trial plots was laid, allowing work to proceed evaluating various weed control strategies.

Objectives/Performance Targets

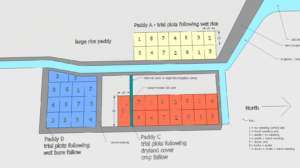

We aimed to lay out three field areas with different prior-year treatments to evaluate the impact of prior year usage. These were areas were Paddy A, in which rice was grown with weeder ducks as normal in 2015, Paddy C, which was not planted in rice in 2015 but instead was kept flooded with several inches of water and was wet-tilled (or “puddled”) at regular intervals, and Paddy B which we attempted to maintain in a dryland state and plant with cover crops. The plan to repeatedly till and replant dryland cover crops was altered somewhat in Paddy B because wet early summer conditions kept the field very wet despite our efforts to treat it as a dryland field.

We aimed to lay out three field areas with different prior-year treatments to evaluate the impact of prior year usage. These were areas were Paddy A, in which rice was grown with weeder ducks as normal in 2015, Paddy C, which was not planted in rice in 2015 but instead was kept flooded with several inches of water and was wet-tilled (or “puddled”) at regular intervals, and Paddy B which we attempted to maintain in a dryland state and plant with cover crops. The plan to repeatedly till and replant dryland cover crops was altered somewhat in Paddy B because wet early summer conditions kept the field very wet despite our efforts to treat it as a dryland field.

Going into 2016, all three fields were puddled and planted with akitakomachi rice seedlings on June 16th. One week after transplanting, the plots were subdivided as indicated in our plot plan. Water depth was maintained at two inches for the first week. On June 24th the experimental plots were subdivided with stakes and string. Plots containing weeder ducks were also divided with nylon netting.

Over the course of the growing season, we managed rice crops in several different ways in order to assess the costs and benefits of different organic approaches to weed control.

Accomplishments/Milestones

In spring of 2016, all fields were puddled. The last tillage of the fields occurred on June 14th, two days before transplanting. At time of transplanting, the water depth was 1-2 inches. Paddies A, B, and C were all transplanted between June 16th and June 17th. On June 24th the water depth was increased to three inches and ducks were added throughout the site in plots labeled 5, 6 and 7.

At this same time plots 3,4, and 6 were inoculated with azolla, but this had fairly little effect due to limited azolla supplies and azolla plant vitality that I will discuss further in “outcomes and impacts.”

By June 28th the ducklings had made a noticeable impact on their plots and weeds were quickly emerging among the crop in areas without ducks. On June 28th we began our regimen of hand weeding and continued it in plots labeled 2, 4, and 7 until August 5th.

By August 5th the plants had developed full canopy and weeding was no longer needed. The ducks were removed from the field and surface waters were drained off. Rainfall was sparse in late summer and fall, and by harvest time, all areas were dry and firm.

On October 1st the grain was ripe and ready for harvest. We harvested each plot separately and weighed the resulting yield. Over the course of the project we also tracked the time invested in weeding and in monitoring the weeder ducklings. I am still in the process of compiling all this data, but will be ready to present it in 2017.

Two unexpected events altered the experiment. The first is that we were unable to get our crop of azolla to thrive during the month of June. Our azolla is azolla caroliniana, native to the Carolinas, and is ordered from an aquarium supply outfit. In both years we ordered two pounds of live plants and attempted to multiply them by growing them in a shallow pond in the farmstead. In 2015, it was slow to grow in May and June but began developing in July. In 2016, growth seemed even slower and by July 4th we did not have enough to effectively deploy azolla as a weed control measure, yet by that time weeds were growing apace.

Using azolla as a floating weed control smother crop was problematic because weeds seemed to gain the upper hand before azolla can become thick enough to suppress them. In 2015, in Paddy C and also in some other fallowed paddies, we had good luck filling large areas with azolla. But in 2016 the azolla seemed to barely grow.

In mid 2016, I had the opportunity to travel to Japan and visit with farmers in the north and south of the country who use non-chemical weed control, primarily relying on weeder ducks. The use of azolla is well described in Japanese farmer Takao Furuno’s book “The Power of Duck.” However I did not see anyone using azolla along with the ducks. One farmer in Hokkaido, Yoshihiro Orisaka said that he had trouble establishing azolla even using heated water and greenhouses and had basically dismissed it as unnecessary for adequate fertility and weed control.

Another factor is that when ducks and azolla are used together, there is a tricky issue of timing. The azolla needs mid-season heat and sunlight to multiply but the ducklings seem to consume the azolla faster than it can grow, at least during the first two or three weeks that ducks and azolla share the paddy. Ultimately, for purposes of weed control, azolla seems to have at least minor compatibility issues with the use of weeder ducks, that are not apparent from a reading of “The Power of Duck.”

The ultimate effect of the weak azolla performance was that the azolla only plots (3) closely resembled the control plots in performance, the azolla plus hand-weeding plots (4) resembled the hand-weeding only plots (2), and the plots with ducks and azolla (6) performed similarly to the plots with only ducks and no azolla (5).

Two unexpected events altered the experiment. The first is that we were unable to get our crop of azolla to thrive during the month of June. Our azolla is azolla caroliniana, native to the Carolinas, and is ordered from an aquarium supply outfit. In both years we ordered two pounds of live plants and attempted to multiply them by growing them in a shallow pond in the farmstead. In 2015, it was slow to grow in May and June but began developing in July. In 2016, growth seemed even slower and by July 4th we did not have enough to effectively deploy azolla as a weed control measure, yet by that time weeds were growing apace.

Using azolla as a floating weed control smother crop was problematic because weeds seemed to gain the upper hand before azolla can become thick enough to suppress them. In 2015, in Paddy C and also in some other fallowed paddies, we had good luck filling large areas with azolla. But in 2016 the azolla seemed to barely grow.

In mid 2015, I had the opportunity to travel to Japan and visit with farmers in the north and south of the country who use non-chemical weed control, primarily relying on weeder ducks. The use of azolla is well described in Japanese farmer Takao Furuno’s book “The Power of Duck.” However I did not see anyone using azolla along with the ducks. One farmer in Hokkaido, Yoshihiro Orisaka said that he had trouble establishing azolla even using heated water and greenhouses and had basically dismissed it as unnecessary for adequate fertility and weed control.

Another factor is that when ducks and azolla are used together, there is a tricky issue of timing. The azolla needs mid-season heat and sunlight to multiply but the ducklings seem to consume the azolla faster than it can grow, at least during the first two or three weeks that ducks and azolla share the paddy. Ultimately, for purposes of weed control, azolla seems to have at least minor compatibility issues with the use of weeder ducks, that are not apparent from a reading of “The Power of Duck.”

The ultimate effect of the weak azolla performance was that the azolla only plots (3) closely resembled the control plots in performance, the azolla plus hand-weeding plots (4) resembled the hand-weeding only plots (2), and the plots with ducks and azolla (6) performed similarly to the plots with only ducks and no azolla (5).

The second setback was that we aimed to valuate a minimal-flooding strategy as an added investigation in the area market plot 8 in Paddy C. We tried to keep this area hydrologically isolated from the adjoining area. However seepage from the neighboring plot through the division dike was such that the plot repeatedly filled with one or two inches depth, keeping the ground perpetually soft. Weeds grew extremely profusely in this plot but the soft, sticky clay made effective cultivation between rows very difficult. Weeding tools balled up with clay and feet sank deep into the mud. The rice also underperformed fully flooded rice.

We have now completed our first year prior-usage plan, and our field trials. What remains is to compile and analyze the data and to try to draw useful conclusions from it in terms of resulting yield and the costs incurred to attain that yield.

We maintained a control plot, which became rife with weeds and had negligible yield. Absent a chemical approach, growers need a coherent strategy for weed control, clearly.

In general, we were able to evaluate azolla, the use of weeder ducks, and the use of hand and mechanical weeding in wet rice. While azolla presented challenges that seemed to limit its effectiveness as a method, the use of weeder ducks, and hand and mechanical weeding remain vital. Having some numbers to gauge their relative merits will surely help us going forward, and I hope this will help other growers and aspiring growers too.

Impacts and Contributions/Outcomes

I believe that we are closer to correctly executing the use of weeder ducks, and that in the big picture, this method has enormous potential value to the project of growing rice in our region. This method has a lot of promise but to be honest it is more challenging than it would appear from a casual reading of Furuno’s “The Power of Duck,” which is an invaluable resource and is very well translated into English, too. Furuno makes it look simple and easy. I have also visited Furuno in person at his farm in Kyushu, Japan, and it is clear that he has the system quite well figured-out. However, despite having leaned heavily on his book, certain practical aspects of duck and rice farming, perhaps obvious to a legacy rice farmer in Asia but not so obvious to Northeasterners, have caused me many stumbles and missteps.

Also a variety of complex factors each have an effect on how well the weeder duck method can work overall. For one thing, predators and disease take their toll on the effectiveness of the method, and lie outside the scope of this experiment. For another, the field leveling before planting must be very precise. If it is uneven, it becomes difficult or impossible to maintain the entire field in a flooded state without very deep water in some areas, which impacts duckling health by making it hard for them to periodically dry off and opening the door to chilling and subsequent disease, and also harms plant health and vigor by submerging too much of the plant at an early growth stage. Much of this is subjective and comes down to judgement that is hard to make without experience.

Yet another factor is selecting rice varieties that work well with the overall method. We have grown a variety called “omirt” which is, I believe, a cousin of “duborskian,” which is grown by some other northeastern rice growers too. However “omirt” has a less stiff and upright posture than some rice, the leaves are large but tend to fan out and hang down. I noticed in some areas of the farm that my newer seedstock from Japan had a more vertical posture and seemed to allow the ducks to navigate and agitate the water around them better. Evaluating varieties within the duck-rice method lies outside the scope of this trial, but is another piece of knowledge we have come at along the way that contribute to a more effective execution.

However the trial does help to firm up some basic facts and methodology about duck-and-rice integrated farming, and I will be able to present the final numbers with some practical guidelines for weed control as I write the final report.

One further potential contribution is that out of boredom I developed a prototype weeder out of a Mantis rototiller, that adds a simple boatlike attachment to the tiller so that it can till between rice plants, in water, without damaging the plants. It is similar to some devices I have seen being used in Asia on YouTube.com, and can be made out of any Mantis rototiller quite easily. It had an impact on weeding hours in our hand weeding plots, that will be detailed when the data are analyzed and published.

Still remaining is our outreach phase. Overall despite difficulties with certain aspects of the experiment and with certain other technical challenges in rice growing, I am very excited about it. We are scheduled to present at the NOFA-VT winter conference in February 2016.

Unfortunately I was not able to host a farm field day during the growing season as originally proposed. However I hope to do so in 2017 either through the Northeastern Grain Growers Association or through NOFA. I will begin working on this shortly.

My written report of the trial results will be made available for conference attendees in February of 2017.