Project Overview

Commodities

- Animals: swine

Practices

- Crop Production: agroforestry

Proposal summary:

If left uncontrolled, pigs would have a negative impact on woodlots, soil, small animals and plant communities. Direct effects of pigs foraging activities include ground cover removal, biting foliage, stems, trunk and roots, debarking trunks and roots, digging up roots isolating them from the soil, and soil compaction. It has been observed predilection for some tree species (Quercus spp. Vs Pinus). The damage caused to trees could be related to food deprivation and feeding the pigs following irregular schedules. In Forest, both low animal visibility and difficult caretakers’ access could complicate routinely inspection of the herd. Additionally, care should be implemented to protect the animals from the exposition to toxic plants and parasites, and from encounters with predators and wild animals.

Establishing an adequate management of pigs in silvopastures allows reaching the ultimate goal of success of trees, forage and animals, in other worlds a sustainable system oriented to implement timber stand improvement strategies together with best animal management practices, improving the ecosystemic functions of the area. Improvements on health and productivity of animals, trees, shrubs and forages, better water and soil quality, increased biological diversity, reduction of erosion, enhancements of wildlife habitat and increases of farmer profit are some of the expected outcomes. An appropriate process of design, planning and management of the operation will minimize the environmental impact, and provide protection of trees, plant and fauna species and their habitats. A flexible system coupled to conscientious monitoring ensures that the planned goals for the wooded area would be accomplished.

To manage grazing pigs two alternate stocking-methods can be implemented: continuous or rotational stocking. Under continuous stocking, pigs are allowed access to the whole paddock area for the total pig growing cycle. In contrast, pigs rotationally stocked are allowed to graze only a portion of the area of the paddock during a certain period of the growing-cycle, after which they are moved to a new portion of the same paddock. This process is repeated sequentially until the growing-cycle ends. This last method reduces the risks of damage to the ground cover and to the soil, by limiting the time of the pigs in a section of the paddocks, allowing for a rest period for the forages providing the opportunity to recover and regrowth. Additional benefits of the rotational stocking method are the reduction in endo-parasites re-infestation risks and getting a better distribution of manure nutrients in the paddock. Previous experiences in Mediterranean forest showed that paddock continuously managed presented greater rooting and soil compaction. Soil degradation was related to high animal densities, while low stocking densities resulted in beneficial soil biological activity and greater soil organic matter.

This project aims to test the hypothesis that to minimize the potential damage to trees and soil in pig silvopasture production systems, it is convenient to implement a rotational stocking system with short periods of occupation per paddock section, and rest periods among successive occupation cycles. The location of the heavy use areas in the central section of the paddocks facilitate the animal mobilization between successive sections to be grazed.

The proposed pig silvopasture rotational system has good chance to be successful in all sustainable dimensions (environmental, social and economic). In this farm, soil nutrients build-up and nutrients leaching are the main environmental risks related to livestock production. These threats can be reduced by the implementation of best management practices such as implementing low pig stocking rates and short graze periods. The trees will play different roles in the proposed system, they will improve animal welfare, by contributing to animals’ thermal comfort either by providing shade during summer, or as windbreak during colder seasons. Additionally, their deeper and more extense root system would allow them to explore deeper areas of the soil profile up-taking soil nutrients while minimizing risks of nutrients runoff and leaching. The farm raises pure breed pigs of heritage breeds and crossbreed pigs which are known by their adaptation to wooden conditions. The mixed hardwood lot that would be included in this silvopasture study has already been fenced and cleared, which is expected to allow enough light penetration to establish and grow a vigorous stand of Bahia grass (Pensacola) forage species that has demonstrated adaptability to some edaphic-climate conditions of Southern USA, such as sandy soil texture, low natural fertility, and acidic soils, and resistance to pigs trampling and rooting behavior. A fundamental feature of this forage species is that grow well under partial shade. The farmers leading the project have an open-minded proactive attitude and are very interested in implementing best management practices to improve the sustainability of their farm. Additionally, Mrs Reaume has employed an effective marketing program based on social media for promoting her farm resulting in a wide online presence. This experience and her naturally social and spontaneous personality will contribute to the successful accomplishment of some of the outreach goals of the project. Key elements to assure success in achieving conservation goals include farmer’s proactive attitude, continuous monitoring and design flexibility.

A major attribute of this project is its ability to leverage existing resources for conducting research, outreach and education activities. These incorporate the personnel, infrastructure and programming within the Center for Environmental Farming Systems (www.cefs.ncsu.edu), CEFS a partnership that includes the NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDA), NC State University and NC A&T State University. NCSU delivers research and sustainable agriculture outreach, and education programs and NCA&T offers research experience and coordinates significant technical services and outreach to independent, limited-resource pork producers throughout the state. A CEFS initiative, NC Choices (www.ncchoices.com), networks pasture-based livestock producers, extension agents, processors, regulators, and allied businesses within this rapidly expanding sector. This project will take advantage of these extensive programs to coordinate and strengthen its research and extension activities and disseminate information and best practices to producers.

As consequence of the re-discovering the potential and benefits of silvopasturing, more pig farmers are considering its implementation as a sustainable way to pursue productivity, environmental advantages and to deliver ecosystem services (Smith et al. 2012).

Project objectives from proposal:

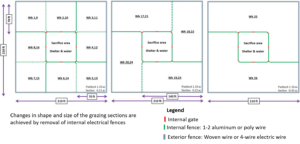

Bahia grass (Paspalum notatum) var Pensacola will be established on three acres of a mixed hardwood area partially cleared (up to a basal area of 50-60 feet2). Following the planting, the area will be divided using electric fencing in three paddocks. Which in turn will be subdivided into nine sections. The central section will be consider as “heavy use area”, shelter and water will be located there. The other eight sections will be considered as “grazing paddocks”, supplemental feed will be provided here. Growing-finishing pigs (from weaning to harvest) at a stocking rate equivalent to 20 pigs/ac, will have continuous access to the central section while the access to the grazing sections would be sequentially allowed during one week/section. As time goes by the shape and size of the sections of the paddocks will evolve as is shown on Figure 1.

[caption id="attachment_928762" align="alignnone" width="300"] Figure 1. Evolution of a rotational stocked paddock during a pig growing cycle of 26 weeks.[/caption]

Figure 1. Evolution of a rotational stocked paddock during a pig growing cycle of 26 weeks.[/caption]

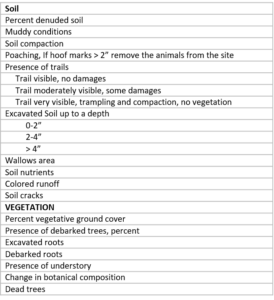

Before starting the pig grazing study, the soil will be sampled (one composed sample per section/ paddock), and vegetation and ground cover assessments (Identifying species, establishing ground cover) will be conducted. The magnitude of soil disturbance will be estimated after ending each pig growing cycle by measuring ground cover percentage, disturbed area (length, width, and depth), and soil compaction (using a penetrometer). The damage to the trees will be also evaluated following Pistoia et al. (2012) forest damage indicators (Table 1). Composed soil samples from each paddock’ section will be collected and analyzed at NCDA consumers’ services soil laboratory for their content of nutrients.

[caption id="attachment_928784" align="alignnone" width="274"]

Table 1 Forest health indicators[/caption]

Table 1 Forest health indicators[/caption]

Crossbred weaned (8 weeks old, aprox 50 lb) pigs (Kune Kune x Large Black and Duroc x Berkshire x Kune Kune), raised in the farm will be used in the study. Pigs will be ad libitum feed with a commercial supplemental feed (16% CP) and will have free access to drinking water. Animal performance will be evaluated as average daily weight gain using pigs weight recorded monthly and the length of the growing cycle. Pigs will be individually weighted in the morning without fasting every four weeks. The amount of supplemental feed offered to the animals will be registered weekly. Feeding efficiency will be also calculated. When possible, data related with carcass (Hot and cold weight) will be collected. Due to health-related risks wallows creation will not be encouraged. Pigs will not use nasal rings.

Labor directly and indirectly involved in the management of the study and its animals will be registered. Similarly, expenses and gain will be recorded to be used in a basic economic analysis (Expenses vs gain ratio). Data will be analyzed for descriptive statistic using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS).