2016 Annual Report for GNC15-211

Evaluating Agricultural Applications of Orchard Nest Boxes and Perches for a Declining Raptor Species: Quantifying Impacts on Pest Rodents and Birds

Summary

New nest boxes installed in Michigan cherry orchards since 2012 have been used extensively by kestrels. In addition, my early dissertation research has shown that these kestrels kill known pest species. We have since installed nest boxes in additional orchards, and we installed artificial perches in some orchards with boxes. We have conducted surveys of fruit-eating birds and rodents in orchards. We have also used video recording systems to document the prey delivered to kestrel nests during the 2013 – 2016 breeding seasons. Finally, we have tracked the movements of female kestrels using GPS data loggers. We are in the process of analyzing this data in order to quantify the effects of kestrel nest boxes and perches on prey.

Objectives/Performance Targets

Objective 1) Effects of kestrel nest boxes and supplemental perches on kestrel presence and fruit-eating bird abundances in orchards:

Objective 2) Effects of kestrel nest boxes and supplemental perches on winter rodent abundances in orchards:

Objective 3) Estimating number of prey removed and extent of prey removal by kestrels breeding in orchard nest boxes:

Accomplishments/Milestones

Objective 1) Effects of kestrel nest boxes and supplemental perches on kestrel presence and fruit-eating bird abundances in orchards:

We completed surveys of fruit-eating bird abundances in orchards with and without active kestrel boxes and perches during the summers of 2015 and 2016. In 2015, we conducted surveys at 30 sites in 15 orchards: five orchards with an active kestrel box, five orchards with an active kestrel box and perches, and five orchards with no kestrel box within 1.6 km. At orchards with active kestrel boxes, we placed sites within 150 m of the box. At orchards with perches, we placed sites within 100 m of a perch. In orchards with sweet and cherry blocks, we placed one site in a block of each crop type; in orchards with blocks of one crop type only, we placed one site at the orchard edge and one in the interior (at least six rows in from the edge row). We placed the two sites in each orchard at least 150 m apart to reduce the chance of observing the same individuals at both sites during a survey visit. In 2016, we conducted surveys at 14 sites in 14 orchards: three orchards with an active kestrel box, four orchards with an active kestrel box and perches, and seven orchards with no kestrel box within 1.6 km or perches. We placed all sites in sweet cherry blocks in 2016.

We conducted 10 minute surveys along 200 m-long fixed-width transects. We conducted a total of 268 surveys over both years. We built models of fruit-eating bird counts and found that counts were significantly lower at sites with an active kestrel box. We did not find a significant effect of perches.

We have also analyzed video recordings of artificial perches in order to assess kestrel perch use. We randomly chose five orchards with active kestrel nest boxes in 2015 in which to install artificial perches. We built the perches from 6.4 m of steel pipe mounted on 1.2 m of rebar buried 0.9 m underground, resulting in a 5.5 m perch height. The perches themselves were 45 cm lengths of 2.54 cm-wide pine dowel attached to the pipe with a floor flange. We installed three perches per orchard; we placed perches within the orchard rows, usually in an open spot where a tree was missing. In 2015, we recorded each perch during daylight hours (06:00 – 21:00 EST) once per week. Kestrel use of the perches was significantly greater in orchard blocks with shorter trees. Kestrels mostly used the perches installed in the youngest orchard blocks; meanwhile, we conducted the fruit-eating bird surveys in mature orchard blocks where kestrels rarely used the perches. So although the perches in mature orchard blocks did not further reduce fruit-eating bird abundances, perches in young blocks could still provide benefits to the kestrels, particularly for fledglings as they leave the nest box (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fledgling kestrels using artificial perch in orchard.

Figure 1. Fledgling kestrels using artificial perch in orchard.

Objective 2) Effects of kestrel nest boxes and supplemental perches on winter rodent abundances in orchards:

During the winter of 2015 – 2016, we surveyed rodents in orchards using camera traps. We conducted surveys between November 2015 and March 2016 at nine orchard sites with blocks of trees that were 3 years old or younger: three orchards with active kestrel boxes during the summer, three orchards with active boxes and supplemental perches, and three orchards with no active box within 1.63 km and no supplemental perches. We conducted surveys in one or two blocks per orchard. In orchards with more than two young blocks, we conducted surveys in two randomly chosen blocks. We set up three camera trapping stations in each block: one in a randomly chosen spot in an interior tree row, and two in randomly chosen edge rows that have continuous edge habitat. Each camera trap station served as a trapping site. We left the camera traps at each site for 24 h. We conducted one to three surveys per site.

We detected no voles during the winter 2015 – 2016 surveys; all detections were of Peromyscus spp. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Peromyscus spp. detected at camera trap in orchard.

Figure 2. Peromyscus spp. detected at camera trap in orchard.

We built an occupancy model and found no effect of date, trap location (orchard edge vs. interior), or the summer presence of an active kestrel nest box on whether or not Peromyscus spp. were present at a trapping site. Lack of sustained snow cover during the winter of 2015 – 2016 prevented us from assessing the effect of snow cover on rodent presence.

We detected rodents during only 19 of 135 trapping opportunities, which suggests that either rodent presence in orchards was low (due perhaps to rodenticide use or lack of snow cover), or detections were low due to the camera trap setup.

We had planned to conduct more camera trap surveys during the winter of 2016 – 2017 in order to determine if rodent presence increased with snow cover, but the repeated lack of sustained snow cover led us to reconsider the usefulness of repeated surveys.

We are currently considering explanations for our results and recommendations for future research.

Objective 3) Estimating number of prey removed and extent of prey removal by kestrels breeding in orchard nest boxes:

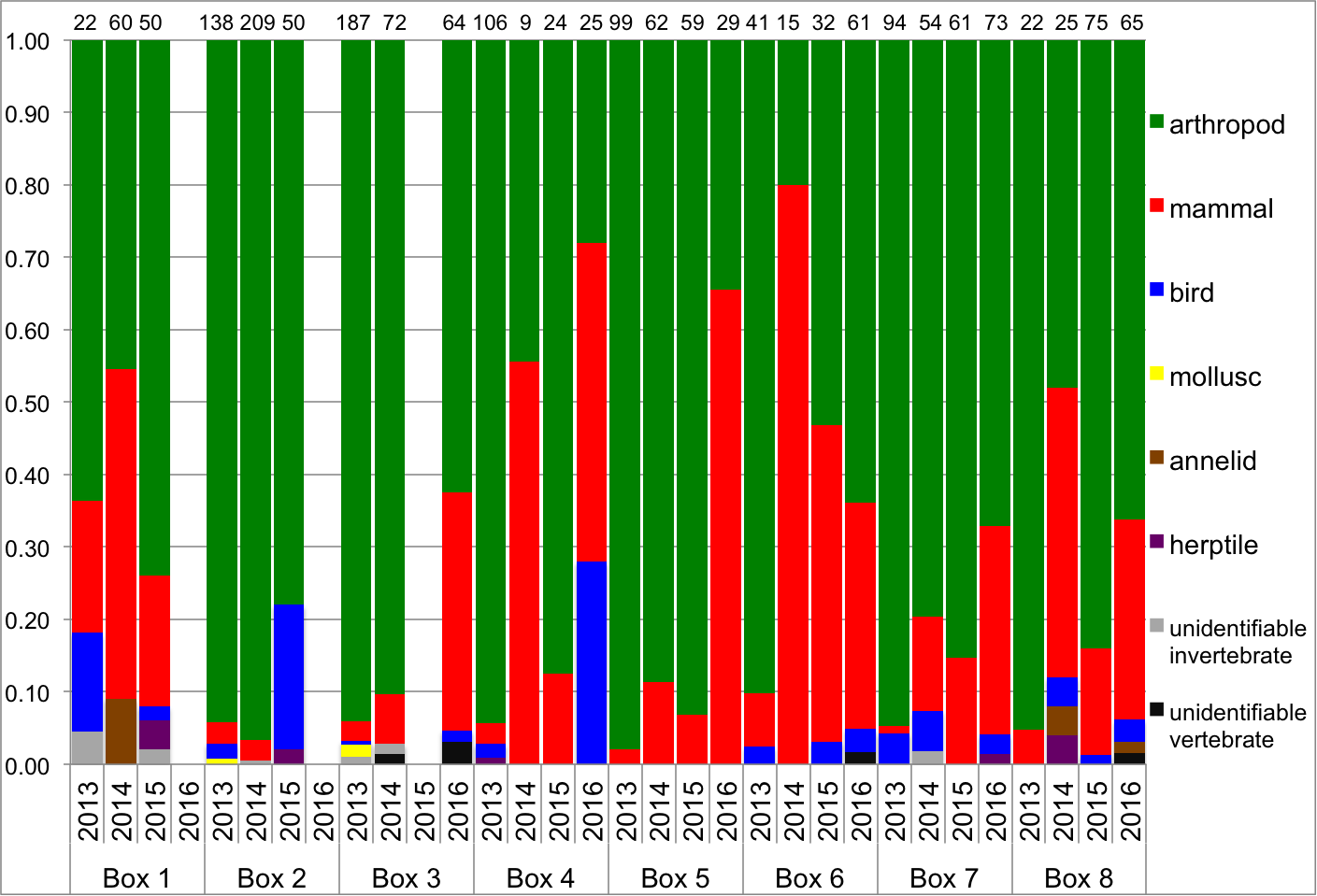

We have used video recording systems to document prey deliveries to kestrel nest boxes during the 2013 – 2016 breeding seasons. Proportions of prey types delivered to nests varied with year and nest box (Figure 3). We are currently finalizing models to explain the number of 1) total prey and 2) rodent prey delivered to a nest in a day. In addition to year and nest box ID, factors of interest in these models include: age of nestlings, growing degree days, precipitation, and the proportion of open habitat (non-forest, non-mature orchard landcover) in the potential kestrel pair’s home range surrounding the nest box.

Figure 3. Proportions of prey types delivered to nests in eight kestrel boxes during the 2013 – 2016 breeding seasons. Data for each bar from two randomly-chosen recording days. Numbers above bars represent total number of deliveries represented.

Figure 3. Proportions of prey types delivered to nests in eight kestrel boxes during the 2013 – 2016 breeding seasons. Data for each bar from two randomly-chosen recording days. Numbers above bars represent total number of deliveries represented.

We also tracked 17 female kestrels using GPS data loggers during the 2015 and 2016 breeding seasons. We were unable to track males because we could not capture them in their nest boxes. We are currently analyzing the GPS data in conjunction with the prey delivery data in order to determine the distances a female kestrel travels from the nest box to hunt and to potentially identify habitat features associated with prey capture (e.g. sources of perches).

Impacts and Contributions/Outcomes

We have given presentations to grower and citizen scientist audiences:

Shave, M. and C. Lindell. Effects of American Kestrel nest boxes and perches on fruit-eating bird activity in cherry orchards. Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market EXPO, Grand Rapids, MI. December 2016. (Talk)

Shave, M. and C. Lindell. Evaluating the agricultural and conservation applications of American Kestrel nest boxes in a fruit-growing region. American Kestrel Symposium, American Kestrel Partnership, The Peregrine Fund, Wilmington, DE. January 2017. (Invited talk)

Shave, M. and C. Lindell. Effects of American Kestrel nest boxes and perches on fruit-eating bird activity in cherry orchards. Tree Fruit IPM School, MSU Extension, Traverse City, MI. February 2017. (Talk)

At these presentations, we distributed a fact sheet on installing and monitoring kestrel nest boxes in orchards.

We have also distributed letters summarizing project results to growers involved in the project.

Finally, we are preparing manuscripts to be submitted in March and May 2017 for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Collaborators:

Associate Professor

Michigan State University

488 Farm Lane RM 203

East Lansing, MI 48224

Office Phone: 5173539874

Website: https://clindell.natsci.msu.edu/