Project Overview

Commodities

- Agronomic: corn, soybeans

Practices

- Animal Production: feed/forage

- Education and Training: decision support system, display, extension

- Farm Business Management: market study, risk management, value added

- Production Systems: organic agriculture

Abstract:

Strong Demanding for Organic Food Vs. Low Adoption of Organic Farming

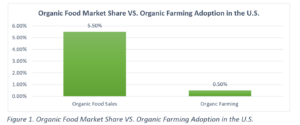

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) described the United States as the most vigorous organic market (Yussefi & Willer, 2003). Data from the Organic Trade Association shows the U.S. had a continuous growth in organic food sales in the past more than two decades. The annual growth rates ranged between 10% and 20% from 1990 to 2016. Organic food sales accounted for 5.5% of total U.S. food sales in 2016. However, compared with the organic food market demanding and market share, the adoption of organic farming in the U.S. remains at a low level (see Figure 1.). Based on data from USDA NASS (2017), only 0.5% of the U.S.’ farmland is under certified organic operation. The adoption rates of organic grains are even lower. Organic corn acreage represents only 0.24% of the nation’s total corn acreage; organic soybeans acreage is 0.16% of the total soybeans acreage.

Undersupply of Organic Grains and Limited Organic Benefits

The low adoption of organic grain farming among American farmers led to recurring shortages of organic grain in the U.S. Due to insufficient supply of organic ingredients, organic food processors had to cut their product lines (Roseboro, 2016). Organic livestock farmers indicated the availability and affordability of organic feed were the biggest challenges they met (Digiacomo & King, 2015). Under-supply and lacking access to organic feed became the barriers for conventional livestock producers to get into the organic sector, and a causal factor that organic livestock producers deregister from organic certification (Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt, & Molinar, 2008). On the other hand, the low adoption of organic grain farming restricted organic agriculture’s positive environmental impacts on soil and water (Cambardella, Delate, & Jaynes, 2015), and limited its benefits to the rural development (Marasteanu & Jaenicke, 2018).

Need for the Study and Research Questions

Organic livestock producers, food processors, and consumers together made a strong call to increase the adoption of organic grain farming in the U.S. (Alonzo, 2016; Doering, 2015; Roseboro, 2016). However, organic grain farming adoption requires farmers to make systemic changes in their operation; farmers need to learn different farming techniques including cultivation, rotations, biological control, and exploring new markets. Faced with the multifaceted challenges, farmers’ decisions of adopting organic grain farming become intricate. The USDA encourages land-grant universities and agricultural organizations to develop and deliver extension education and research programs to promote organic farming and solve issues related to organic agriculture issues. In this context, with the mission of promoting organic grain farming and facilitating farmers’ organic farming conversion, organic specialists and extension educators need to understand: 1) farmers’ motivations for adopting organic grain farming; 2) challenges impede farmers’ adoption in organic grain farming; 3) feasible strategies to overcome the challenges, 4) beneficial outcomes of organic grain farming, and 5) farmers’ needs of education on organic grain farming.

Though past studies may shed some light on these topics of information (Constance & Choi, 2010; Duram, 1999; 2000, Mccann et al., 1997; Middendorf, 2007; Stock, 2007, Stofferahn, 2009), their studies did not specifically focus on grain farmers, and most of their sampled farmers are horticulture crop and livestock producers. Given the large differences in management and operation between the different commodity types, farmers’ motivations and challenges of organic grain farming adoption may be very different from horticulture crop and livestock operation. Research specifically focused on grain farmers in the U.S. is limited and tends to become outdated (Lockeretz & Madden, 1987; Wernick & Lockertz, 1977). This study aims to answer the following research questions:

1) What are the factors that motivate farmers to adopt organic grain farming?

2) What are the challenges impeding farmers’ adoption of organic grain farming?

3) What are the strategies farmers employ to overcome challenges to organic grain farming?

4) What are the benefits experienced in organic grain farming adoption?

5) What are the farmers’ needs for extension and education regarding organic grain farming?

This research project will enrich and update the body of knowledge on understanding farmers’ organic grain farming adoption in the U.S.

Methods

This research utilized social science methodology with a mixed-method research design. The first phase of this study is a qualitative study through semi-structured in-depth interviews with 18 organic farmers in the state of Iowa. The purpose of interviewers is to gain a deep understanding of why farmers adopted organic grain farming and the holistic process of their adoption of organic grain farming. After analyzed the interview, we developed an instrument based on the findings of the interview. In the quantitative study stage. We sent surveys to all organic farmers who have organic grain operation in the state of Iowa. We received 258 completed surveys. Statistical analysis was conducted on the returned surveys.

Main Findings

Through both interviews and surveys with organic farmers, we found the motivations of organic grain farming adoption include health concern, values on biodiversity, conservation tradition, soil improvement, farm viability, self-challenge, and nostalgia for the old-way farming. The main challenges farmers faced include weed control, time stress, intensive labor and management, machinery, transitional crops marketing, and financial risk during the transitional period. To confront the multiple challenges, farmers have employed different sets of strategies to overcome the challenges which include operational strategies, learning strategies, and financial strategies. Farmers have experienced both economic and non-economic benefits after adopt organic grain farming. The economic benefits include profitability, farm viability, and competing yields. Non-economic benefits include agroecology, enjoyments, human health, and ideological validation. In terms of needs for extension education, organic grain farmers hope to have more programs related to on-farm research, young farmers' education, broader population outreach, and more off-season learning activities. Farmers perceive field day and one-on-one mentorship as effective education formats. The topics they need for more education are weed management, crop rotation, marketing, soil biology, and cover crop management.

Project Outcomes

By sharing this project’s findings with extension educators and organic specialists at multiple conferences and organizations’ meetings. This research project helped extension educators, farmers’ organic specialists and to gain a better understanding of farmers’ comprehensive adoption process of organic grain farming, including motivations, challenges, strategies, benefits, and needs for programs.

References

Alonzo, A. (2016). Infographic: Feed shortage limits organic poultry sector growth. WATT PoultryUSA. Retrieved from https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/25882-organic-poultry-production-growth-hurt-by-feed-shortages

Cambardella, C. A., Delate, K., & Jaynes, D. B. (2015). Water quality in organic systems. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 4(3), 60. doi:10.5539/sar.v4n3p60

Constance, D. H., & Choi, J. Y. (2010). Overcoming the barriers to organic adoption in the United States: A look at pragmatic conventional producers in Texas. Sustainability, 2(1), 163-188. doi: 10.3390/su2010163

DiGiacomo, G., & King, R. P. (2015). Making the transition to organic: Ten farm profiles. (Report No. 207981). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Doering, C. (2015). Organic farmers face growing pains as demand outpaces supply. USATODAY. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2015/08/05/organic-farmers-face-growing-pains-demand-outpaces-supply/31116235/

Duram, L. A. (1999). Factors in organic farmers' decision making: Diversity, challenge, and obstacles. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 14(1), 2-10. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300007955

Duram, L. A. (2000). Agents' perceptions of structure: How Illinois organic farmers view political, economic, social, and ecological factors. Agriculture and Human Values, 17(1), 35-48. doi: 10.1023/A:1007632810301

Lockeretz, W., & Madden, P. (1987). Midwestern organic farming: A ten-year follow-up. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 2(2), 57-63. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300001582

Marasteanu, I. J., & Jaenicke, E. C. (2018). Economic impact of organic agriculture hotspots in the United States. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 1-22. doi: 10.1017/S1742170518000066

McCann, E., Sullivan, S., Erickson, D., & De Young, R. (1997). Environmental awareness, economic orientation, and farming practices: a comparison of organic and conventional farmers. Environmental Management, 21(5), 747-758. doi: 10.1007/s002679900064

Middendorf, G. (2007). Challenges and information needs of organic growers and retailers. Journal of Extension, 45(4), Article 4FEA7. Available at https://www.joe.org/joe/2007august/a7.php

Roseboro, K. (2016). Multiple efforts underway to increase U.S. organic farm land. The Organic and Non-GMO Report. Retrieved from http://non-gmoreport.com/articles/multiple-efforts-underway-to-increase-u-s-organic-farm-land/

Sierra, L., Klonsky, K., Strochlic, R., Brodt, S., & Molinar, R. (2008). Factors associated with deregistration among organic farmers in California. Davis, CA: California Institute for Rural Studies.

Stock, P. V. (2007). ‘Good farmers’ as reflexive producers: An examination of family organic farmers in the US Midwest. Sociologia Ruralis, 47(2), 83-102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00429.x

Stofferahn, C. W. (2009). Personal, farm and value orientations in conversion to organic farming. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 33(8), 862-884. doi: 10.1080/10440040903303595

USDA NASS. (2017). USDA certified organic survey 2016 summary. Retrieved from https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/zg64tk92g/70795b52w/4m90dz33q/OrganicProduction-09-20-2017_correction.pdf

Wernick, S., & Lockeretz, W. (1977). Motivations and practices of organic farmers. Compost Science, 18(6), 20–24.

Yussefi, M., & Willer, H. (2003). The world of organic agriculture 2003: Statistics and future prospects. Retrieved from http://orgprints.org/13883/1/willer-yussefi-2003-world-of-organic.pdf

Project objectives:

The overall objective of this dissertation research project was to increase the understanding of farmers’ adoption decisions and the adoption process of organic grain farming to the body of knowledge. The specific research objectives are:

- Identify the factors motivating farmers’ decisions on adopting organic grain farming.

- Identify the challenges impeding farmers’ adoption of organic grain farming.

- Identify strategies farmers employed to overcome the challenges of adopting organic grain farming.

- Explore the benefits of organic grain farming that farmers have experienced.

- Explore the educational approaches and resources that farmers sought as they considered organic grain farming adoption.

- Develop a framework that illustrates how farmers’ motivating factors, challenges, strategies, benefits, and education affect the adoption process of farmers' organic grain farming.