Final report for FNC16-1048

Project Information

Farm #1

Lighthouse Farm is a 160 acre grass-based farm in East Central Minnesota. We raise grass fed beef and pastured pork. The 90 acres of tillable land is in permanent pasture and hay fields. About half of the farm is grazed only, and the other half is primarily for hay production, with some grazing available depending on the success/failure of the growing season. John Mesko has degrees in agronomy and farm management from Purdue University. He has been rotationally grazing his beef cattle in the summer and feeding them hay in the winter for 10 years. John is also the Executive Director of the Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service.

Farm #2

Mark Mathews has been raising and selling grass hay on his 40 acre farm for 15 years. Mark and his family also raise chickens, eggs, beef, goats and vegetables. Mark is also a computer engineer.

Recent emphasis at SARE, NRCS and other sustainable agriculture outlets regarding soil health has raised interest in pasture management and grazing. Frequently, at grazing conferences and workshops, winter bale grazing is touted as a great way to add nutrients to the soil through spent hay litter left behind after the cattle are done grazing. I’ve heard many farmer-presenters make comments to the effect, “With what bale grazing can do for your soils, you can afford hay at almost any price.” In the north country, making hay is an essential component of producing cattle on grass, often limiting the amount of grazing land available on a particular operation in a particular year, as some land needs to be reserved for hay production.

At the aforementioned events, I often ask if anyone has any data which can reinforce the claims of the value of spent hay litter after bale grazing. None has been produced.

The cost of winter feed is generally considered the largest expense for most grazers, and the need to make that feed on the farm often limits the size of the grazing herd. If hay could be affordably outsourced, grass fed herds could grow larger if most or all of a farm’s land could be grazed. In an attempt to know the true cost and benefit of purchased hay in a bale grazing scenario, we must somehow measure the benefit of that hay litter on the pasture in subsequent years.

The problem this proposal addresses is this: After taking all costs and benefits into consideration, what is the value of spent hay litter from purchased hay? How much can a farmer afford to pay for hay to be brought on to their farm to be used in winter bale grazing?

- Measure the impact of spent hay litter on the productivity of pasture.

- Based on the impact of the spent hay litter, determine a value for said litter, and subsequently the value of purchased hay used in winter bale grazing systems

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Process

Baseline soil tests taken in the spring of 2016 report average soil fertility and soil health. Forage tests from 2015 hay production and 2016 hay production are in the table below.

|

Measure |

2015 Hay |

2016 Hay |

|

Crude Protein (Dry Matter) |

7.7% |

10.7% |

|

Relative Feed Value |

80 |

104 |

|

TDN (est, %) |

55.2% |

64.0% |

|

Sampling Date |

April 20, 2016 |

July 5, 2016 |

While forage quality improvements from 2015 to 2016 are impressive, it should be noted that the 2016 samples were taken days after the hay was made, and the 2015 samples were taken 9-10 months after baling. More samples will be taken of the 2016 hay in early 2017 in order to compare the quality changes over winter.

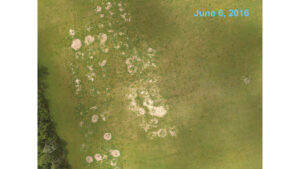

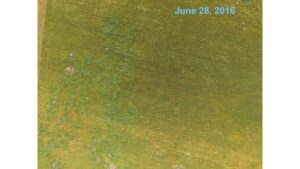

The bale grazing site was grazed from September 5, 2016 through September 25, 2016 (20 days) by 14 yearling steers and heifers. Calves averaged 725 lbs. at the time they were turned out, and after 20 days averaged 755 lbs. The average daily rate of gain was 1.75#. This number is lower than what we normally achieve on our farm. We think part of this is due to the regrowth being too short to really allow for efficient grazing, and we think part of this is due to the fact that we split the yearlings off from the rest of the herd, and there was a day or two of stress on the yearlings from being separated. They may have delayed getting right at grazing immediately. In 2017, delayed hay harvest due to excessive and untimely rains had several negative impacts. First, it led to a poorer quality hay crop than anticipated. It also caused the regrowth on the test site to be such that it was unable to be grazed as we had anticipated in our plan. Finally, because of the late date, we were unable to host a field day showing any significant differences in regrowth from the check site to the test site. Instead, we compiled our key data and learning into a webinar broadcasted on December 15, 2017.

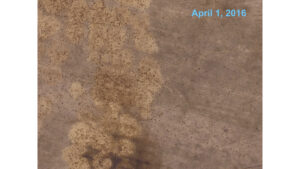

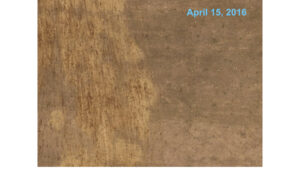

- We put bales out in 2015-16 too far apart. In the spring the hay litter was not covering completely, which has resulted in spotty regrowth. I expected the cattle to scatter the hay further than they did. I am only going to allow 8-10 feet between bales this winter.

- In some instances we used small square bales as well. These bales need some kind of feeder to keep cattle from wasting it. We’ve actually used round bale feeders for feeding square bales and it works well.

- We’ve put out as much as 3 weeks of feed at a time, with little “wastage.” I’m not sure what the far end of this is. Could an entire winter’s worth of hay be fed at once? That won’t be a part of this study, but it would make a change in how cattle overwintering could be handled.

Results Summary

We learned several things. First, our objective was to determine how much farmers could afford to pay for hay when using a winter bale grazing system. The answer is that we expect the true value of hay is 1.5 times the nutrient value of the hay, as determined by forage testing.

Secondly, we learned that in most cases, no fencing is needed to keep cattle out of bales until ready to graze them. In most situations we saw little difference between allowing free choice bale grazing vs. controlled bale grazing.

We also learned to not be concerned about manure clumps. We saw little or no improvement in the breakdown of the hay litter post dragging.

Going forward, I will recommend the practice of purchasing quality hay for bale grazing at 1.5 times the nutrient value price, and encourage farmers to keep bales 8 feet apart.

The research: how much can you afford to pay?

This project was focused on determining the true value of purchased hay, including the nutritional value as well as the value of the benefits to the soil by bale grazing that purchased hay. Using the attached spreadsheet, (linked at: https://fyi.uwex.edu/forage/files/2014/01/Hay-Pricing-StructureV2.xls )developed by University of Wisconsin Extension, plugging in the numbers from our hay analysis, we have an adjusted nutritional value of $50.05/ton of purchased hay. The purchased hay costs $85/ton, delivered and staged for grazing. This leaves the value of the remaining hay litter at $85 - $50.05 = 34.95/ton. Let’s try to determine the value to the soil of the bale grazed hay:

On average, 35 tons of hay were bale grazed on the 14 acre site in each of 2 winter grazing seasons. The cattle consumed the nutritional value, but $34.95/T was not consumed. It remained on site as non digestible, either in manure, or in spent hay litter. So, a total of (35T Hay * $34.95T)/14ac. = $87 of hay litter was applied per acre to the test site.

Assuming a hay cost of $40/1000# bale, what did we get for that $87/ac.?

1. We saw an average yield increase of 0.5T/ac. At $80/T, that equates to $40/ac.

2. We saw crude protein values increase by an average of 2.1%. Using the UW calculations, where CP is valued at $2/1%, we see an increase in hay quality valued at $4.20/T * 3.6T/ac. = $15.12/ac.

3. We also saw an average increase in RFV of 18 points. Again, using the UW numbers, where RFV = $0.25/pt., we see an increase of $4.50/T *3.6T/ac. = $16.20/ac.

4. We saw an average increase in the value of soil nutrition of $11.49/ac.

These are not necessarily additive values, as the value attributed to a crude protein increase is likely incorporated into the value attributed to an increase in RFV.

The return to the farm of the spent hay litter is either:

1. Yield increase + crude prot. increase + soil nutrition increase

2. Yield increase + RFV increase + soil nutrition increase

or

1. $40 + $15.12 + $11.49 = $66.61

2. $40 + 16.20 + $11.49 = $67.69

or about $67/ac.

To get this back to a value per bale, we take the $67/ac * 14ac = $938, divided by 35T/hay fed = $26.80/T as the value of spent hay litter

This means that our $80/T purchased hay contained $50.05 worth of nutrition + $26.80 worth of benefit to the soil, for a total value of $76.85/T

So, in answer to the question, “how much can you afford to pay for hay?” our example shows that the $80/T we paid is possibly a little high. But more importantly, we have determined there is significant value to the soil of spent hay litter! In our case, the nutritional value of the hay was $50.05/T, less than the purchase price. At the very least, we’ve established that valuing hay on nutritional value alone is an insufficient measure.

In a general sense, farmers can think about the following formula when considering the purchase price of hay for bale grazing:

Price (P) = Nutritional Value (NV) + Soil Value (SV)

Where NV is determined by nutrient analysis, plugged into the UW spreadsheet, and where SV is estimated to be a 10% yield increase, a 15% RFV increase, and a soil nutrient increase of 20%

Additional Information Needed

Much more work could be done on this issue. A more robust testing protocol could be developed, which would include a measure of the percentage of hay going unconsumed, rather than an estimate. It would also include additional sites and a longer testing window. In the short window of time for this test, weather made too much of an impact. I recommend a 7-10 year study which would have better controls for testing consistency.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

In addition to the Dec. 2017 webinar, we hosted several farm tours in the winter of 2016-17 and throughout 2017 which were not a part of our original plan. These were informal tours organized in response to individual conversations with groups of farmers as well as individual farmers who heard about the project and wanted to come see.

|

Date |

Type of Group |

Number |

|

January 14, 2017 |

MN Organic Conf Attendees |

6 |

|

March 10, 2017 |

NE MN Grazers |

12 |

|

April 26, 2017 |

Local Farm Community |

19 |

|

July 30-31, 2017 |

Farming Neighbors |

5 |

|

October 29, 2017 |

Northern MN Grazers Group |

20 |

|

November 1, 2017 |

Local Amish Community |

4 |

|

December 15, 2017 |

Live Webinar |

15 |

While this outreach was different than the field day planned, much more detail was able to be shared and farmers learned more and were much more engaged. Refreshments were provided for on site events.

Learning Outcomes

We learned several things. First, our objective was to determine how much farmers could afford to pay for hay when using a winter bale grazing system. The answer is that we expect the true value of hay is 1.5 times the nutrient value of the hay, as determined by forage testing.

Secondly, we learned that in most cases, no fencing is needed to keep cattle out of bales until ready to graze them. In most situations we saw little difference between allowing free choice bale grazing vs. controlled bale grazing.

We also learned to not be concerned about manure clumps. We saw little or no improvement in the breakdown of the hay litter post dragging.

Going forward, I will recommend the practice of purchasing quality hay for bale grazing at 1.5 times the nutrient value price, and encourage farmers to keep bales 8 feet apart.

Project Outcomes

We learned several things. First, our objective was to determine how much farmers could afford to pay for hay when using a winter bale grazing system. The answer is that we expect the true value of hay is 1.5 times the nutrient value of the hay, as determined by forage testing.

Secondly, we learned that in most cases, no fencing is needed to keep cattle out of bales until ready to graze them. In most situations we saw little difference between allowing free choice bale grazing vs. controlled bale grazing.

We also learned to not be concerned about manure clumps. We saw little or no improvement in the breakdown of the hay litter post dragging.

Going forward, I will recommend the practice of purchasing quality hay for bale grazing at 1.5 times the nutrient value price, and encourage farmers to keep bales 8 feet apart.